Abstract

Background

In order to design studies assessing the optimal use of bone-targeted agents (BTAs) patient input is clearly desirable.

Methods

Patients who were receiving a BTA for metastatic prostate or breast cancer were surveyed at two Canadian cancer centres. Statistical analysis of respondent data was performed to establish relevant proportions of patient responses.

Results

Responses were received from 141 patients, 76 (53.9%) with prostate cancer and 65 (46.1%) with breast cancer. Duration of BTA use was <3 months (15.9%) to >24 months (35.2%). Patients were uncertain how long they would remain on a BTA. While most felt their BTA was given to reduce the chance of bone fractures (77%), 52% thought it would slow tumour growth. Prostate patients were more likely to receive denosumab and breast cancer patients, pamidronate. There was more variability in the dosing interval for breast cancer patients. Given a choice, most patients (49–57%) would prefer injection therapy to oral therapy (21–23%). Most patients (58–64%) were interested in enrolling in clinical trials of de-escalated therapy.

Conclusion

While there were clear differences in the types of BTAs patients received, our survey showed similarity for both prostate and breast cancer patients with respect to their perceptions of the goals of therapy. Patients were interested in participating in trials of de-escalated therapy. However, given that patients receive a range of agents for varying periods of time and in different locations (e.g. hospital vs. home), the design of future trials will need to be pragmatic to reflect this.

Keywords: Bone metastases, Breast cancer, Prostate cancer, Patients, Survey

1. Introduction

Despite the widespread use of bone-targeted agents in the care of patients with bone metastases from prostate and breast cancer, questions regarding the optimal; choice of agent, dose, dosing frequency, and duration of therapy remain unanswered [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Our research group is interested in designing and performing pragmatic de-escalation trials in both breast and prostate cancer patients. However, before undertaking this research, it is important to survey potential patients regarding this type of study with respect to their understanding of their disease and use of their bone-targeted therapies (i.e. denosumab, zoledronate, pamidronate or clodronate). The information obtained will facilitate appropriate pragmatic trial designs, which will positively impact patients’ potential willingness to participate.

This report summarizes the conduct and findings of a survey designed to collect information from Canadian patients with breast or prostate cancer regarding their views of their current treatment regimen. In addition, their opinions regarding the possibility of less frequent treatment administrations and participation in potential research studies to assess the effectiveness of this treatment option were also sought. While we are aware of similar patient surveys around the use of bone-targeted agents for osteoporosis [7] and multiple myeloma [8], we are not aware of published work in patients with metastatic bone disease from solid tumors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Survey development

The survey was designed to collect specific information about the use of current bone-targeted therapy and patients’ perception of the goals of this treatment and alternative treatment schedules. Second, the survey gathered information regarding their perspectives on the concept of de-escalated bisphosphonate therapy, designed to help the study team develop an understanding of how patients would value a change in their therapy. Our survey was conceived and developed using an iterative approach by the research team with backgrounds in oncology and epidemiology, including expertise in survey design. The survey is provided in a supplemental appendix.

2.2. Study population

Patients attending outpatient clinics at two Canadian cancer centres (The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre in Ottawa and the Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre in Toronto, Canada) who were receiving or had recently been receiving bone-targeted therapy for bone metastases from either prostate or breast cancer were approached. The survey was available in both paper and online formats (implemented via www.fluidsurveys.com), whichever the patient preferred to use, and took about 10 min to complete. The survey was open to patients seen between August 1st and October 31st, 2012. Local institutional research ethics board (REB) approval for the study was granted at both participating hospitals. However, given the REB requirement that no personal patient identifiers could be collected, we were unable to collect information on the number of patients who took the survey away from clinic but then chose not to complete it. As a result, a response rate cannot be calculated.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The survey consisted of close-ended multiple-choice and hybrid questions (i.e. choose-one-and specify) which were analyzed using a descriptive summary of findings in the form of frequencies and percentages using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, Washington) and SAS software (version 9.2, SAS, Cary, North Carolina). There were no formal hypotheses tested using the data. This data was used to qualitatively judge the respondents’ views of their current treatments and to determine their willingness to be treated with de-escalated bone-targeted therapy to allow the study team to clarify the value and feasibility of a future trial around this clinical question. Analyses were performed to present the overall response profile, as well as responses within the breast cancer and prostate cancer subgroups. Bar plots were generated to help present categorical data findings.

3. Results

3.1. Respondent population characteristics

A total of 141 patients responded, and included totals of 65 (46.1%) and 76 (53.9%) patients diagnosed with breast cancer and prostate cancer, respectively (Table 1). All patients had bone metastasis. A total of 100% of breast cancer patients and 94.7% of prostate cancer patients were aware that they had received treatment with a bone-targeted agent at some point. Respondents had received bone-targeted agents for: <3 months (17.0%), between 3 and 12 months (37.6%), between 12 and 24 months (22.0%), and >24 months (19.1%); 4.3% of patients did not respond. Patients varied in the amount of time for which they expected to remain on therapy: 44.7% did not know for how long, 43.2% indicated as long as their doctor keeps prescribing it, 5.0% believed it to be as long as they remain well enough to attend their centre to receive it, and 6.4% did not respond. These response patterns were similar for breast cancer and prostate cancer patients with a few small differences noted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of respondent population.

| Respondent characteristics |

Distribution of responses |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Prostate cancer | Overall | |

| Number of respondents | 65 (46.1%) | 76 (53.9%) | 141 |

| Cancer spread to bones? | |||

| Yes | 65 (100%) | 76 (100%) | 141 (100%) |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Previous bone targeted agent therapy? | |||

| Yes | 65 (100%) | 72 (94.7%) | 137 (97.2%) |

| No | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.9%) | 3 (2.1%) |

| No response | 0 | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Duration of bone targeted agent therapy? | |||

| <3 months | 8 (12.3%) | 16 (21.1%) | 24 (17.0%) |

| 3–12 months | 21 (32.3%) | 32 (22.7%) | 53 (37.6%) |

| 12–24 months | 14 (21.5%) | 17 (22.4%) | 31 (22.0%) |

| >24 months | 22 (33.8%) | 5 (6.6%) | 27 (19.1%) |

| No response | 0 (0%) | 6 (7.9%) | 6 (4.3%) |

| Expectations, bone targeted agent treatment duration? | |||

| 2 years | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| As long as I am well enough | 5 (7.7%) | 2 (2.6%) | 7 (5.0%) |

| As long as my doctor prescribes | 30 (46.2%) | 31 (40.8%) | 61 (43.2%) |

| Unknown | 29 (44.6%) | 34 (44.7%) | 63 (44.7%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| No response | 1 (1.5%) | 8 (10.5%) | 9 (6.4%) |

3.2. Current treatment

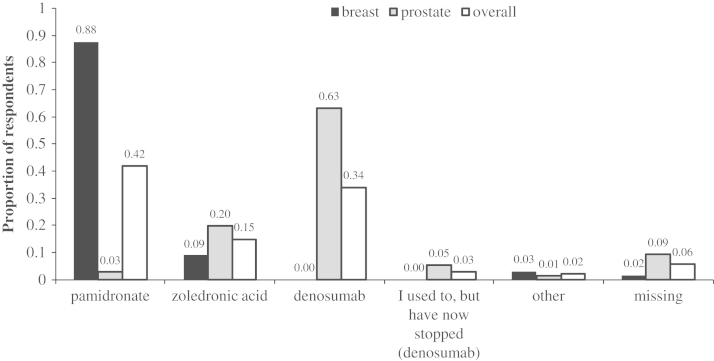

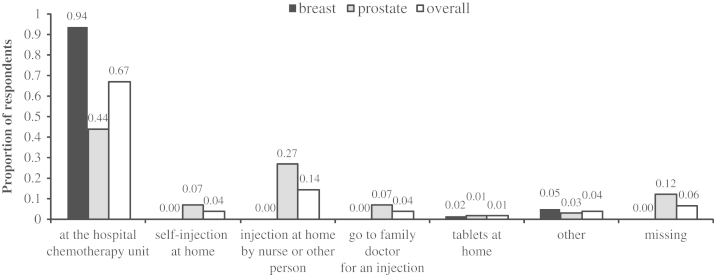

Among prostate cancer patients, the most commonly administered agent was denosumab (63.1%, as well as an additional 5.3% who in the past had received denosumab), followed by zoledronic acid (19.7%) (Fig. 1). Overall 44.7% of patients received their treatment at the hospital chemotherapy unit, while 27% received treatment via injections administered at home by a nurse or another individual (Fig. 2). A total of 31 patients (40.8% of all prostate cancer patients, or 45.6% of those responding to the related question) reported being aware of potential side effects of their treatment. According to patients’ descriptions, the potential side effects of bone targeted agents were; diarrhoea, constipation, vomiting, fatigue, flu-like symptoms, osteonecrosis of the jaw, hypocalcaemia, bone pain and water retention.

Fig. 1.

Summary of bone-targeted agents patients were currently receiving.

Fig. 2.

Summary of where respondents currently receive their bone-targeted therapy.

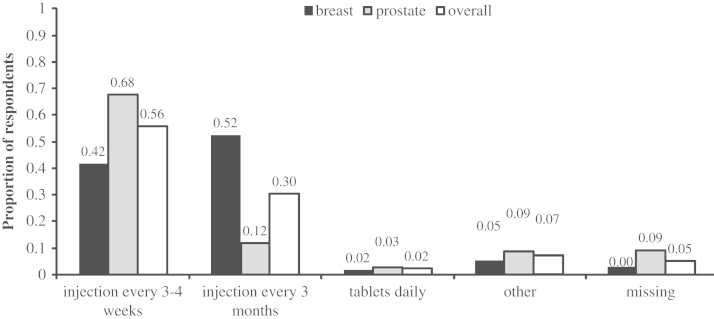

Within the breast cancer cohort, the most commonly used agent was pamidronate (87.7%), followed by zoledronic acid (9.2%; Fig. 1). Overall, 93.8% of patients reported receiving their treatments in the chemotherapy unit at their hospital (Fig. 2). Overall, 34 patients (52.3%) were receiving their treatment every 3 months (Fig. 3). A total of 28 patients (43.1%) reported awareness of potential side effects, similar to those described by prostate cancer patients.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of bone-targeted agent administration.

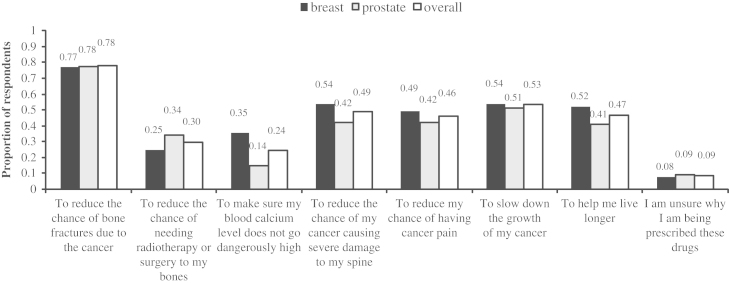

3.3. Patient's viewpoints regarding the indication for current bone-targeted treatment

The most commonly reported reasons were: to reduce the chance of bone fractures due to cancer (78.0%), to slow the growth of cancer (53.2%), to reduce the chance of spinal damage (49.0%), to prolong survival (46.8%), and to reduce the chance of cancer pain (46.1%) (Fig. 4). Fewer patients indicated that it was related to prevent the need for radiotherapy/surgery to bones (29.8%) or to the management of hypercalcaemia (24.1%).

Fig. 4.

Summary of why patients believe they receive bone-targeted treatment.

3.4. Patients’ viewpoints regarding potential changes in therapy

The majority of respondents with prostate cancer (78.9% overall, or 93.5% of those that responded to the related question) and breast cancer (75.4% overall, or 87.3% of those that responded to the related question) would be willing to take a reduced dose of their medication if it were associated with the same clinical benefits as their current dose. Similarly, the majority of respondents with prostate (67.1% overall, or 79.7% of those responding to the related question) and breast cancer (69.2% overall, or 88% of those responding to the related question) indicated they would be happy taking the medication less often (i.e. leaving the dose unchanged but receiving it less frequently) if the clinical benefits were unchanged.

Eighteen and a half percent and 30.3% of breast and prostate cancer respondents, respectively, indicated a lack of interest in changing from their current 3–4 week regimen. If reducing the dose would lead to fewer side effects, 64.6% of prostate cancer and 46.1% of breast cancer patients indicated an interest in taking a reduced medication schedule and dose.

When asked if they would prefer a daily oral medicine or an injection in the hospital every 1–3 months, 21.1% of prostate cancer patients and 23.5% of breast cancer patients indicated a preference for taking oral medication daily, while 57.9% and 49.2% preferred an injection every 1–3 months. An additional 19.5% and 13.4% of patients did not respond. Overall, 39.2% of prostate cancer patients and 35.4% of breast cancer patients indicated a willingness to administer their own medication via an injection. When asked if they would be willing to enter a trial randomising between monthly and 3 monthly therapy, 64.6% of prostate patients and 58.2% of breast cancer patients indicated a willingness to participate in such a study.

4. Discussion

Despite the widespread use of bone-targeted agents in the care of patients with bone metastases from prostate and breast cancer, a number of important and practical clinical questions remain around optimising their use. In order to design and perform pragmatic clinical trials in these populations, it is important to obtain patient treatment information, perceptions and opinions that will help guide trial design to ensure sufficient participation. This is of particular interest for studies evaluating treatment de-escalation where it is critical to ascertain patient's willingness to participate. To our knowledge, we are the first team to implement use of this type of survey in these patient populations, although a number of de-escalation studies are either reported [4], [5], [6], [7] or are ongoing [8].

Our survey demonstrates that Canadian breast cancer patients are more likely to receive pamidronate, whereas prostate cancer patients are more likely to receive either denosumab or zoledronic acid. These differences reflect not only that the drugs proven to be efficacious in these populations are different (i.e. only denosumab and zoledronic acid improve outcomes in prostate cancer), but also that the funding system for these agents in Ontario differs. Any trial looking at de-escalated therapy will need to take these factors into account. Our findings also suggest that clinical trials evaluating single agents such as zoledronic acid or denosumab [4], [5], [6] will not lead to broad changes in clinical practice in both disease sites. Trials will therefore need to reflect the diversity of treatments offered. In addition, for prostate cancer patients, such a trial will need to reflect the fact that a significant number of patients have switched from zoledronic acid to denosumab when funding for denosumab became available, thus future studies may have to allow for bisphosphonate use prior to denosumab treatment in the inclusion criteria.

Patients in our survey population had been on bone-targeted agents for variable periods of time, again meaning that future trials will need to be reflective of this, and be flexible in the length of time a patient has been on a prior bone-targeted agent prior to study entry. To date, of the published trials [4], [7], only one [5] did not specify the maximum length a patient could have been on a prior agent.

Interestingly, many patients perceived that the bone-targeted agent was slowing the growth of their cancer. Given that these agents have shown no effect on either overall survival or progression-free survival in breast cancer [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. [6], [14] or prostate cancer [15], [16], there may be a need to better inform patients of this fact.

Preference for injectable therapy over oral therapy [17], contrary to our findings from a previous study [18], could reflect the fact that most patients have not received an oral bone-targeted agent for metastatic disease. However, the practical advantages of an injectable therapy and the lack of need for extra-care (taking the medication with water, not laying down shortly after PO administration) in an elderly patient population should not be ovelooked.

There are limitations to our study. Our sample was recruited from two cancer centres in Ontario, Canada and therefore reflects prescriptions practices in that Province. In addition, as the REB requirement was to allow no patient identifiers on the questionnaires, we could not tell how common it was for patients to refuse participation (i.e. in place of a denominator for response rate, which we do not have). As a consequence, it is possible that our responding cohort consists of better informed, more motivated patients which may not be representative of all patients receiving treatment with bone targeted agents. This too could be reflected by the large number of breast cancer patients who are already receiving 3-monthly bone-targeted therapy [2].

5. Conclusion

In an era of personalised medicine, involvement of patients in the design of future clinical trials is increasingly important. Although our results suggest that patients still have misconceptions around the reasons for receiving bone-targeted agents, the similarities between prostate and breast cancer patients are interesting as both patient populations were aware of the main indications and toxicities of these agents. Patients are interested in trials of de-escalated therapy. However, given that patients receive a range of agents for varying periods of time and in different locations (hospital vs. home) means that the design of future trials will need to reflect this and be very pragmatic.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2013.05.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Kuchuk I, Clemons M, Addison C. Time to put an end to the one size fits all approach tobisphosphonate use in patients with metastatic breast cancer? Current Oncology. 2012;19(5):e303–e304. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amadori D, Aglietta M, Alessi B. ZOOM: A prospective, randomized trial of zoledronic acid (ZOL; q 4 wk vs q 12 wk) for long-term treatment in patients with bone metastatic breast cancer (BC) after 1 yr of standard ZOL treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(9005) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amir E, Freedman O, Carlsson L. Randomized feasibility study of de-escalated (Every 12 wk) versus standard (Every 3 to 4 wk) intravenous pamidronate in women with low-risk bone metastases from breast cancer. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182568f7a. published online first. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman R. Bone cancer in 2011: prevention and treatment of bone metastases. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2011;9(2):76–78. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman RE, Wright, J, Houston, S, et al..Randomized trial of marker-directed versusstandard schedule zoledronic acid for bone metastases from breast cancer, ASCO Annual Meeting 2012 Chicago, IL, Journal of Clinical Oncology, pp 511. 2012.

- 6.Kuchuk I, Addison C, Simos D, Clemons M. A national portfolio of bone oncology trials-the Canadian experience in 2012. Journal of Bone Oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2012.09.001. published online first. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryzner KL, Burkiewicz JS, Griffin BL. Survey of bisphosphonate regimenpreferences in an urban community health center. Consultant Pharmacist. 2010;25(10):671–675. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2010.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low E, Morgan KEUK. Patient Perspectives of Bisphosphonate Treatment Highlight a Lack of Knowledge On Therapeutic Benefits and Strong Preferences for Choice and Location of Treatment. 54th ASH Meeting. Abstract 2074. 2012.

- 9.Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3314–3321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double- blind study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:5132–5139. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassinello Espinosa J, Gonzalez Del Alba Baamonde A, Rivera Herrero F, Holgado Martin E. SEOM guidelines for the treatment of bone metastases from solid tumors. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2012;14(7):505–511. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0832-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Poznak C, Temin S, Yee G. American Society of Clinical Oncology executive summary of the clinical practise guideline update on the role of bone-modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:1221–1227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Poznak C, Von Roenn J, Temin S. American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update: recommendation on the role of bone modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(2):117–121. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hortobagyi G, Theriault R, Porter L. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal complications in patients with breast cancer and lytic bone metastases. Protocal 19 Aredia Breast Cancer Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:1785–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612123352401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2011;5;377(9768):813–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R. Zoledronic Acid Prostate Cancer Study Group. Arandomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;2;94(19):1458–1468. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripathy D, Body JJ, Bergstrom B. Review of ibandronate in the treatment of metastatic bone disease: experience from phase III trials. Clinical Therapeutics. 2004;26:1947–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clemons M, Dranitsaris G, Ooi W. A Phase II trial evaluating the palliative benefit of second-line oral ibandronate in breast cancer patients with either a skeletal related event (SRE) or progressive bone metastases (BM) despite standard bisphosphonate (BP) therapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;108:79–85. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9583-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material