Abstract

AIM: To investigate the role of blood transfusion in TT viral infection (TTV).

METHODS: We retrospectively studied serum samples from 192 trans fusion recipients who underwent cardiovascular surgery and blood transfusion between July 1991 and June 1992. All patients had a follow-up every other week for at least 6 months after transfusion. Eighty recipients received blood before screening donors for hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV), and 112 recipients received screened blood. Recipients with alanine aminotransferase level > 2.5 times the upper normal limit were tested for serological markers for viral hepatitis A, B, C, G, Epstein Barr virus and cytomegalovirus. TTV infection was defined by t he positivity for serum TTV DNA using the polymerase chain reaction method.

RESULTS: Eleven and three patients, who received anti-HCV uns creened and screened blood, respectively, had serum ALT levels > 90 IU/L. Five patients (HCV and TTV:1; HCV, HGV, and TTV:1; TTV:2; and CMV and TTV:1 ) were positive for TTV DNA, and four of them had sero-conversion of TTV DNA.

CONCLUSION: TTV can be transmitted via blood transfusion. Two recipients infected by TTV alone may be associated with the hepatitis. However, whether TTV was the causal agent remains unsettled, and further studies are necessary to define the role of TTV infection in chronic hepatitis.

Keywords: blood transfusion; TT viral infection; hepatitis C; antibody, viral

INTRODUCTION

After hepatitis B screening in blood donors, the addition of antibody against he patitis C virus (anti-HCV) has further reduced the occurrence of post-transfusion hepatitis dramatically[1,2]. However, there still exists some post- transfusion hepatitis, that may be caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV) and other viruses. Among them hepatitis G virus (HGV) infections once had been considered[1,3,4]. In 1997, a novel virus named TT virus (TTV) was reported by Japan[5], and the virus is known to be an unenveloped, single-stranded DNA virus with a sequence of 3739 bases. The virus can transmit through blood transfusi on[5]. In Japan, 12% of blood donors and 46% of chronic non-A-G hepat itis patients have detectable TTV DNA in their serum[6]. Taiwan is an area prevalent for viral hepatitis[7,8], and the role of TTV has not documented. We therefore studied the role of TTV infection in those patients who received blood transfusions, using serum samples in a previous prospective study of post-transfusion hepatitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively studied stored serum samples, which were collected in a prior prospective study for post-transfusion HCV infection[1] for TTV infection. These serum samples were collected from 192 blood recipients who underwent cardiovascular surgery at the Cathay General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan from July 1991 to June 1992, before universal screening of blood donors for anti-HCV that was implemented in July 1992. All serum samples were stored at -70 °C. Among them, 19 recipients were healthy hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers with serum alanine aminotransferase levels ( ALT ) < 45 IU/L. No recipient had had a blood transfusion within 12 months before recruitment. Recipients already positive for anti-HCV before transfusion, and those having alcoholic, drug-related, autoimmune, or ischemic hepatitis were excluded.

Eighty and 112 recipients received anti-HCV unscreened and screened blood, respectively. For anti-HCV screening in the study, a second-generation enzyme immunoassay ( EIA-III, UBI HCV EIA, United Biomedical, Inc., New York, NY) was used. All recipients were tested for serum ALT levels and anti-HCV to exclude the presence of possible viral hepatitis C before transfusion. After transfusion, all patients had a follow-up every other week until 6 months after transfusion, and blood samples were also collected.

Recipients with two successive ALT > 2.5 times the normal upper limit were tes ted for serologic markers for viral hepatitis A, B, C, E, G, TTV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and CMV as well as antinuclear antibodies. Acute viral hepatitis A, B, and E were defined if the recipients were positive for immunoglobulin M antibodies to hepatitis A virus (IgM anti-HAV; HAVAB-M EIA, Abbott Lab., Abbott Park, IL), hepatitis B core antigen [IgM anti-HBc; Corzyme-M (rDNA) Abbott Lab.], and hepatitis E virus (IgM anti HEV; HEV IgM ELISA, Genelabs Diagnostics PTE Ltd, Singapore Science Park, Singapore). Sero-conversion of anti-HCV using the EIA method and/or HCV ribonucleic acid (HCV RNA) using reverse transcriptio n-nested polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay with primers derived from the 5’untranslated region of HCV genome was used to define acute viral hepatitis C[9]. A titer of ≥ 1:64 for IgM antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus (IgM anti-EBV, IP Azyme, EB/VCA IgM, Savyon Diagnostic Ltd., Beer Sheva, Israel) and CMV (IgM anti-CMV, IP Azyme CMV IgM, Savyon Diagnostic Ltd.) using the immu no-peroxidase assay were defined as having acute EBV and CMV hepatitis. Sera were tested for antinuclear antibodies using the immuno-fluorescent method (Fluoro HEPANA, Medical & Biological Lab., Nagoya, Japan).

Patients with positive HBsAg ( Auszyme, Abbott Lab.) were also tested for hepatitis Be antigen [HBeAg; HBe (rDNA) EIA, Abbott Lab.] and antibody to hepatitis delta virus (anti-HDV; Wellcozyme, Wellcome Diagnostics, England ) using the EIA method.

The occurrence of sero-conversion of GBV-C/ HGV RNA was defined as acute HGV infection. The GBV-C/HGV RNA was identified with RT-PCR using nested primers from the 5’-untranslated region of the viral genome as previously described[10].

The diagnosis of acute TTV infection was based on the occurrence of sero-conversion of TTV DNA determined using PCR method with semi-nested primers as previously described[6,11]. Briefly, DNA was extracted from 100 μL of serum using QIAMP Blood kit (QIAGEN Ltd., Crawley, UK) and re-suspended in 50 μL of elution buffer. For the first round of PCR, 25 μL of reaction mixture containing 2 μL of the cDNA sample, 1 × PCR buffer (10 mM tris-HCl pH 9.0, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2 0.01% gelatin, and 0.1% Triton X-100), 10 mM of each dNT P, 100ng of each outer primer T-1 (sense: ACAGACAGAGGAGAAGGCAACATG-3’) and T-2 (anti-sense : 5’-CTACCTCCTGGCATTTTACC-3’), and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase was am plified in a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT) for 30 cycles. On e microliter of the PCR products was re-amplified for another 30 cycles with 100 ng of inner primers, T-3 (sense: 5’-GGCAACATGTTATGGATAGACTGG-3’) and T-4 (anti-sense: CTGGCATTTTACCATTTCCAAAGTT-3’). The amplified products were separated by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test, Yates’ corrected Chi-square, and one-tailed Fisher’s exact test where appropriate.

RESULTS

In the 80 and 112 recipients who received anti-HCV unscreened and screened blood, respectively, the gender (male/female = 43/37 vs 66/46, P = 0.48), age [mean ± SD, (range)] = 44 ± 20 years (4-76 years) vs 45 ± 22 years (4-75 years, P = 0.52), number of HBsAg carriers (9 vs 10, P = 0.60), and volume of blood transfsed [mean ± SD, (range)=18.0 ± 14.9 units (2-67 units) vs 18.8 ± 12.7 units (1-70 units), P = 0.58] were not signif icantly different between the two groups. Eleven (13.8%) and three (2.7%, P = 0.004) subjects who received unscreened and screened blood had serum ALT levels > 90 IU/L, respectively (Table 1). Among them, four (36.4%) and one (33.3%, P = 0.72) patients were positive for TTV DNA, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data of 14 Patients with Post-trans fusion hepatitis

| Patient | Age (yr)/gender | Peak ALT (IU/L) | Hepatitis |

| Unscreened Blood | |||

| SYS | 58/F | 1043 | HCV |

| CLT | 66/M | 527 | HCV |

| LCSG | 74/F | 264 | HCV |

| PTT | 76/M | 109 | HCV, TTV |

| SGM* | 43/M | 93 | HCV |

| LWG | 67/M | 257 | HCV, HGV |

| STS | 60/M | 455 | HCV, HGV, TTV |

| CSPC** | 48/F | 218 | HBV, CMV |

| CST | 30/M | 236 | CMV, HGV |

| LYY | 13/F | 103 | TTV |

| CSG | 64/M | 159 | 159 |

| Screened Blood | |||

| CPL | 65/F | 645 | CMV, TTV |

| HWL | 65/F | 541 | CMV |

| CHL*** | 63/M | 101 | HBV |

Patients were treated with interferon alfa 2b;

HBsAg ( + ), HBeAg ( - ), anti-HBe ( + ), anti-HDV ( - ); ***HBsAg ( + ), HBeAg ( + ), anti-HBe ( - ), anti-HDV ( - ); #Positive for TTV DNA before transfusion.

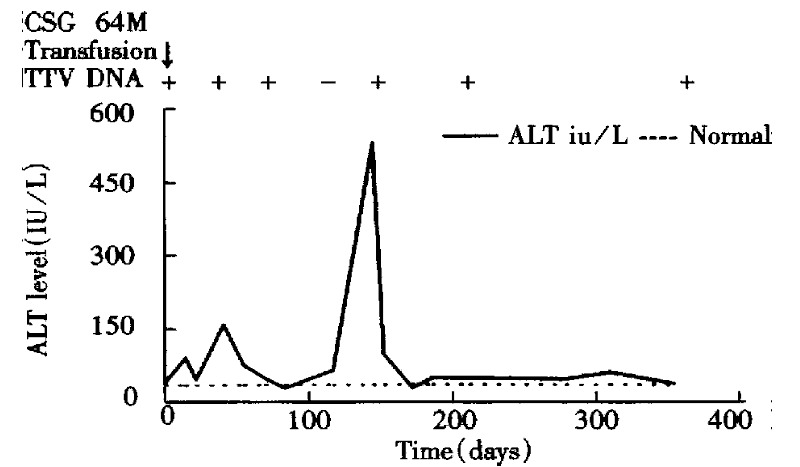

One patient (CSG) who received unscreened blood was positive for TTV DNA before transfusion (Figure 1). His maximum serum ALT level was 159 IU/L, and maximum serum total bilirubin level was 18.8 μmol/L. He was negative for any markers of active hepatitis A-G.

Figure 1.

A 64-year-old man who received unscreened blood was positive for TTV DNA before and after transfusion.

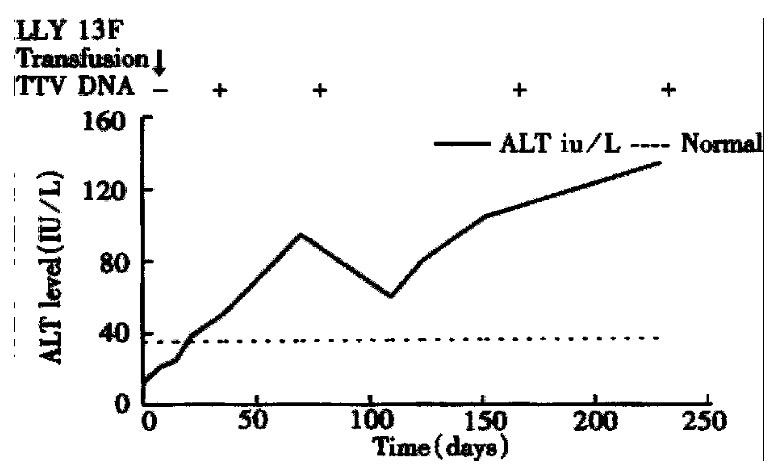

The remaining four subjects had a sero-conversion of TTV DNA. Only one (LYY) of them was negative for markers of hepatitis A-G, and her abnormal serum ALT level and TTV DNA were detected in the 3rd and 6th weeks after transfusion, respe ctively (Figure 2). Her maximum serum ALT level was 103 IU/L, and maximum serum total bilirubin level was 8.6 μmol/L. Two other patients (CSG, LYY) had abnormal serum ALT levels and positivity for TTV DNA until 6 months after transfusion.

Figure 2.

A 13-year-old girl who received unscreene d blood had sero-conversion of TTV DNA after transfusion.

The remaining three patients all had a co-infection with other types of he patitis. All three patients had a transient appearance of TTV DNA lasting only 2 weeks. The first patient (PTT) had HCV and TTV co-infections. His HCV RNA, TTV DNA, abnormal serum ALT activity, and anti-HCV were detected at the 12th, 12th, 18th, and 18th weeks, respectively. His maximum serum ALT level was 109 IU/L, and maximum serum total bilirubin level was 13.7 μmol/L. He continued to have abnormal liver tests and positivity for HCV RNA until 27 weeks after transfusion when he finished the follow-up.

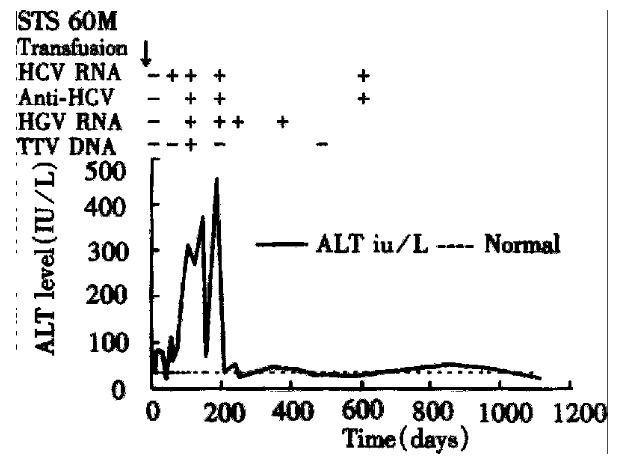

The second patient (STS) had HCV, HGV, and TTV co-infection (Figure 3). His HCV RNA, abnormal serum ALT level, anti-HCV, HGV RNA, and TTV DNA were detected at the 2nd, 2nd, 8th, 8th, and 12th weeks after transfusion, respectively. His max imum serum ALT level was 455 IU/L, and maximum serum total bilirubin level was 1.5 mg/dL. His HGV RNA lasted for 24 weeks, and his HCV RNA and abnormal serum ALT levels remained until 37 months after transfusion when he expired from congestive heart failure.

Figure 3.

A 60-year-old man who received unscreened blood had sero-conversion of TTV DNA after transfusion. He was co-infected with viral hepatitis C and G.

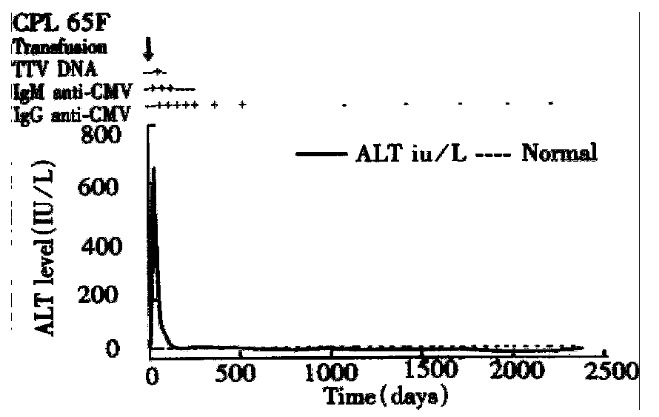

The third patient (CPL) had CMV and TTV co-infection (Figure 4). Her abnormal serum ALT level and IgM and immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-CMV and TTV DNA were detected at the 2nd, 3rd, and 6th weeks after transfusion, respectively. Her maximum serum ALT level was 645 IU/L, and maximum serum total bilirubin level was 6.8 mg/dL. Her IgM anti-CMV lasted 4 months, and IgG anti-CMV lasted 38 months. Her serum ALT levels returned to normal at the 13th month after transfusion.

Figure 4.

A 65-year-old woman who received anti -HCV screened blood had sero-conversion of TTV DNA after transfusion. She was co-infected with cytomegalovirus infection.

None of our patients with post-transfusion hepatitis developed fulminant hepatic failure. Of the five patients with TTV infection, only one patient (CPL), who was co-infected with CMV hepatitis, developed jaundice clinically.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, four patients experienced sero-conversion of TTV DNA after receiving blood unscreened or screened for anti-HCV. Our findings are consistent with recent studies that TTV infection can be transmitted through blood trans fusion[6,12-14]. Although the screening of blood donors with anti-HCV had dramatically reduced the post-transfusion hepatitis from 13.8% to 2.7%, one recipient who received anti-HCV-screened blood developed post-transfusion TTV infection. Our data also showed that the rate of TTV infection is not different between patients who received unscreened and screened blood. Therefore, anti -HCV screening in donor blood does not seem to affect the rate of TTV infection.

Three of our patients had co-infection of TTV infection and other types of hepatitis, and the appearance of serum TTV DNA was only transient. Although all three patients had abnormal serum ALT levels lasting more than 6 months, their chronic hepatitis was not necessary related with TTV infection. In Japan, the prevalence of TTV infection was 12% in blood donors and was 46% in chronic hepatitis and/or cirrhosis sufferers[6]. The prevalence of TTV infection in Tai wan was 10% in healthy adults and was 15%-36% in those with chronic hepatitis B or C[11], findings similar to those in Japan[6,14]. These findings indicate that TTV infection is common in East Asia. But, the rate of TTV-r elated post transfusion hepatitis in the present study was only 2.1%. The relative low prevalence of TTV-related post-transfusion suggests that most TTV infections are mild beyond detection clinically. This is further supported by only one patient with TTV infection developing jaundice clinically. Our findings are consistent with recent reports that most post-transfusion TTV infections are likely to be mild clinically[11,12,15,16].

In the present study, all three patients with HGV infection were co-infect ed with other types of hepatitis. This is consistent with the findings that risk factors of HGV carriage to other body-fluid transmitted viruses. One percent of healthy adults in Taiwan have detectable HGV RNA[3,4,17,18].

Our data also show that two patients, who were previously diagnosed as non-A-G hepatitis, were positive for TTV DNA. The one patient with detectable serum TTV DNA before and after transfusion most likely had TTV infection before transfusion. Another patient with sero-conversion of TTV DNA after transfusion is likely to have had an acute TTV infection. Both of these patients had chronic hepatit is with abnormal serum ALT levels for more than 6 months, and their chronic hepatitis may have been related to TTV infection. One patient (LYY) had a recent followed-up 7 years after the blood transfusion. She had a serum ALT level, non-d etectable serum TTV DNA, and positivity for anti-HCV (authors’ unpublished observation). She has been a nurse for one year, and she becomes positive for anti-HCV 6 months ago. The blood transfusion 7 years ago was not likely the cause of HCV infection. Although we were determined to exclude other kinds of hepatitis, it is possible that these two patients may have developed hepatitis other than TTV infection. Further studies are necessary to understand the role of TTV infection in chronic hepatitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the clinical servic es of Chung-Ming Chen, MD., Herng-Cheng Chiou, MD. Chung-Ze Lu, MD., Lon-Th iam Ong, MD., Hung-Shun Lo, MD., Junn-Zih Wu, MD. Thay-Hsung Chen, MD., Divi sion of Cardiology and Ms. Ti-Yin Hwang, Division of Gastroenterology, Cathay G eneral Hospital.

Footnotes

Grant from Cathay Groups No. 8003.

Edited by You DY

References

- 1.Huang YY, Yang SS, Wu CH, Shih WS, Huang CS, Chen PH, Lin YM, Shen CT, Chen DS. Impact of screening blood donors for hepatitis C antibody on posttransfusion hepatitis: a prospective study with a second-generation anti-hepatitis C virus assay. Transfusion. 1994;34:661–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34894353459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aach RD, Stevens CE, Hollinger FB, Mosley JW, Peterson DA, Taylor PE, Johnson RG, Barbosa LH, Nemo GJ. Hepatitis C virus infection in post-transfusion hepatitis. An analysis with first- and second-generation assays. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1325–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111073251901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Hepatitis G virus--a true hepatitis virus or an accidental tourist. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:795–796. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvis LM, Davidson F, Hanley JP, Yap PL, Ludlam CA, Simmonds P. Infection with hepatitis G virus among recipients of plasma products. Lancet. 1996;348:1352–1355. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)04041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto H, Nishizawa T, Kato N, Ukita M, Ikeda K, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Hepatol Res. 1998;10:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen DS. Hepatitis B virus infection, its sequence and prevention in Taiwan. In: Okuda K, Ishak KG, eds. Neoplasms of the liver. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo. 1987:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SS, Lai YC, Wu CH, Chen TK, Lee CL, Chen DS. Acute viral hepatitis in alien residents in Taiwan: a hospital- based study. Taiwan J Gastroenterol. 1997;14:185–191. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Yang PM, Lai MY, Sheu JC, Wang TH, Chen DS. Intrafamilial transmission of hepatitis C virus: the important role of infections between spouses. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:900–903. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Chen W, Hsiang SC, Lai MY, Chen DS. Amplification of GB virus-C/hepatitis G virus RNA with primers from different regions of the viral genome. J Med Virol. 1997;51:284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao JH, Chen W, Hsiang SC, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Prevalence and implication of TT virus infection: minimal role in patients with non-A-E hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1999;59:307–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<307::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlton M, Adjei P, Poterucha J, Zein N, Moore B, Therneau T, Krom R, Wiesner R. TT-virus infection in North American blood donors, patients with fulminant hepatic failure, and cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;28:839–842. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmonds P, Davidson F, Lycett C, Prescott LE, MacDonald DM, Ellender J, Yap PL, Ludlam CA, Haydon GH, Gillon J, et al. Detection of a novel DNA virus (TTV) in blood donors and blood products. Lancet. 1998;352:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto H, Akahane Y, Ukita M, Fukuda M, Tsuda F, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Fecal excretion of a nonenveloped DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion non-A-G hepatitis. J Med Virol. 1998;56:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naoumov NV, Petrova EP, Thomas MG, Williams R. Presence of a newly described human DNA virus (TTV) in patients with liver disease. Lancet. 1998;352:195–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cossart Y. TTV a common virus, but pathogenic. Lancet. 1998;352:164. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen W, Liu DP, Wang JT, Shen MC, Chen DS. GB virus-C/hepatitis G virus infection in an area endemic for viral hepatitis, chronic liver disease, and liver cancer. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1265–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alter HJ, Nakatsuji Y, Melpolder J, Wages J, Wesley R, Shih JW, Kim JP. The incidence of transfusion-associated hepatitis G virus infection and its relation to liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:747–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]