Abstract

The association of sarcoidosis with multiple myeloma is not well known. Including this case report, 12 cases of patients with both sarcoidosis and multiple myeloma have been reported in the literature. The skeletal lesions of both conditions have many clinical and radiological similarities, and unless clinicians are aware of the association and the possibility of dual pathologies, the diagnosis of multiple myeloma in patients known with sarcoidosis may be missed. We present a case of a patient known with longstanding sarcoidosis who was found to have multiple lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) involving the pelvis and both proximal femurs. Histological analysis revealed the presence of both non-necrotising granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis, and sheets of plasma cells consistent with a plasma cell neoplasm.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Sarcoidosis, Lymphoproliferative disorder, Skeletal, Case report

1. Case presentation

A 50 year old female machinist presented to our general orthopaedic outpatients׳ department with a 5 month history of right groin and buttock pain of spontaneous onset. She had a background history of hypertension and biopsy-proven sarcoidosis. The pain radiated to the right knee and had progressively worsened over the preceding month. She had not experienced any constitutional symptoms, had no previous malignancies, and had been on a daily dose of 20 mg prednisone and 150 mg azathioprine for 4 years as part of her treatment for sarcoidosis.

Examination revealed an antalgic gait with a painful and stiff right hip. The pain was most severe in flexion and internal rotation.

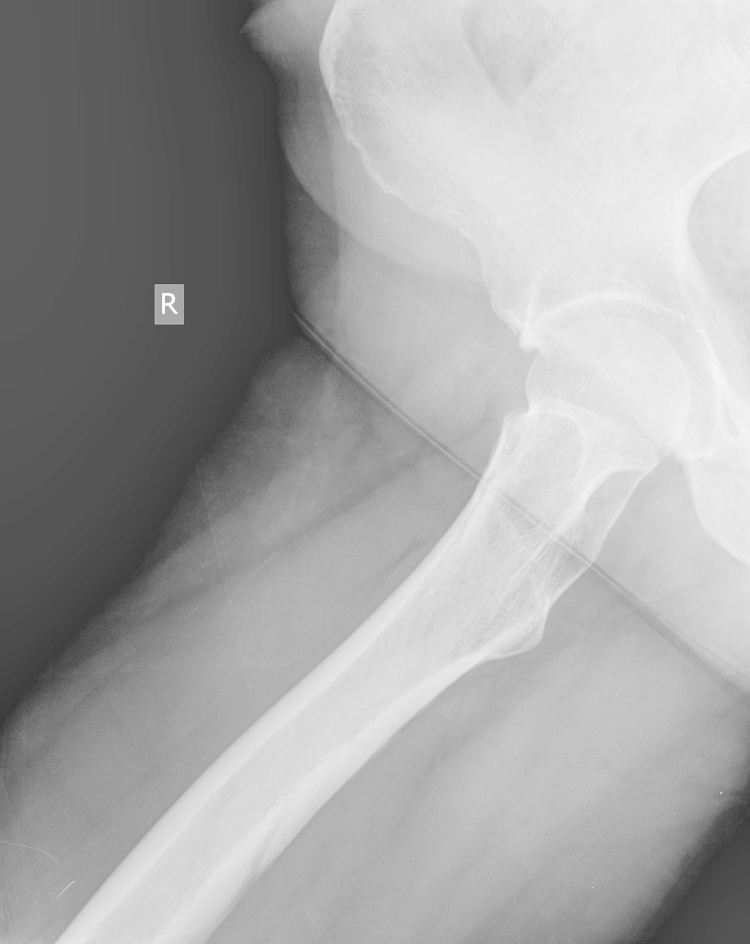

An anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and lateral radiograph of the right hip demonstrated moderate degenerative changes of both hips (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Anteroposterior radiograph of pelvis at presentation.

Fig. 2.

Lateral radiograph of right hip at presentation.

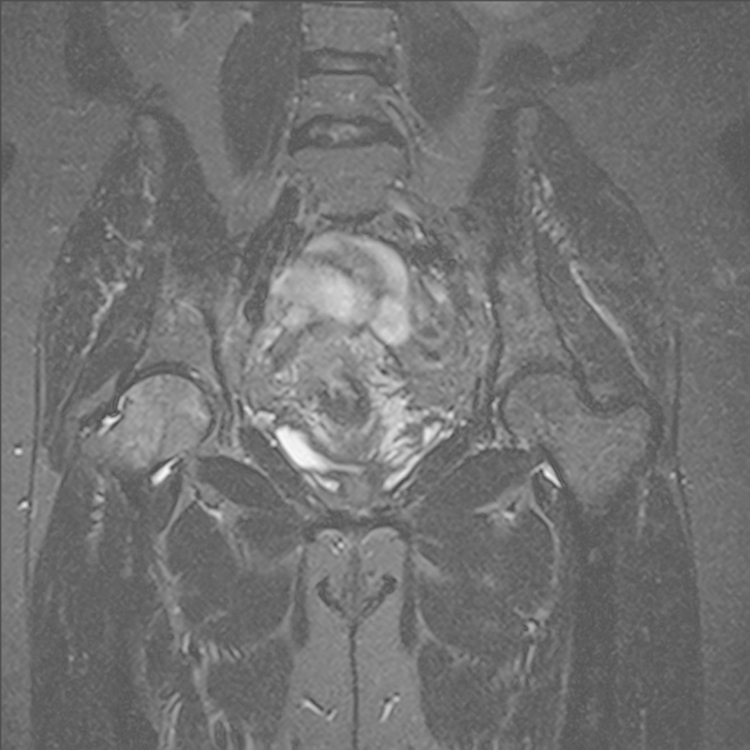

A provisional differential diagnosis of early avascular necrosis (AVN) or femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) was made. Renal function and calcium, magnesium and phosphate (CMP) levels were normal, C-reactive protein was 8.5 mg/l and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 40 mm/h. An MRI revealed no evidence of AVN, with areas of intermediate to high signal in the right femoral head and neck, as well as the left femur and pelvis (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The MRI findings were in keeping with sarcoidosis. Further clinical work up was recommended to exclude other causes such as metastatic lesions or myeloma if clinically indicated.

Fig. 3.

STIR coronal MRI showing areas of signal abnormality in the right femoral head.

Fig. 4.

T2W sagittal MRI showing multiple areas of intermediate to high signal in the right femoral head and pelvis.

By this time the patient׳s symptoms had continued to progress, and a second AP pelvis X-ray (Fig. 5) revealed a lytic lesion in the inferior neck of the right femur with a Mirels׳ score of 11 [1]. After consultation with both the musculoskeletal tumour and arthroplasty units, it was decided to perform a biopsy of the femoral head/neck and total hip replacement as a single stage procedure.

Fig. 5.

Anteroposterior radiograph at follow-up showing a lytic lesion in the inferior neck of the right femur.

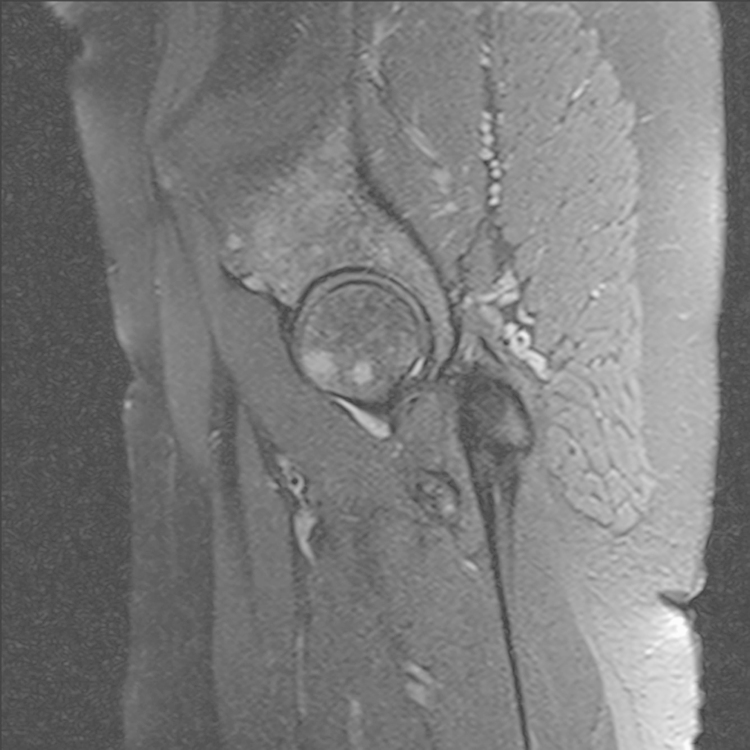

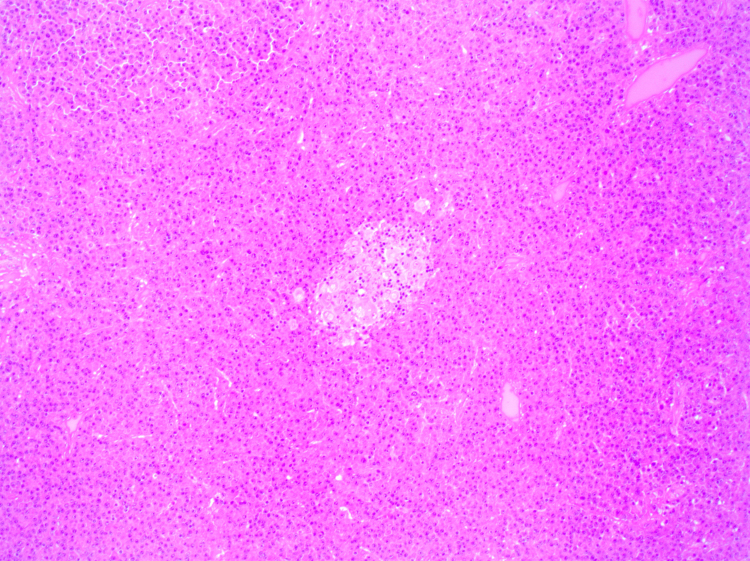

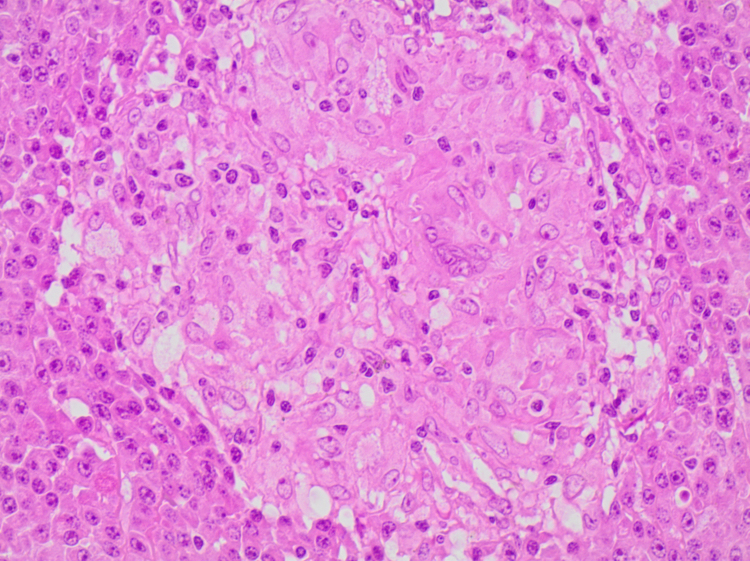

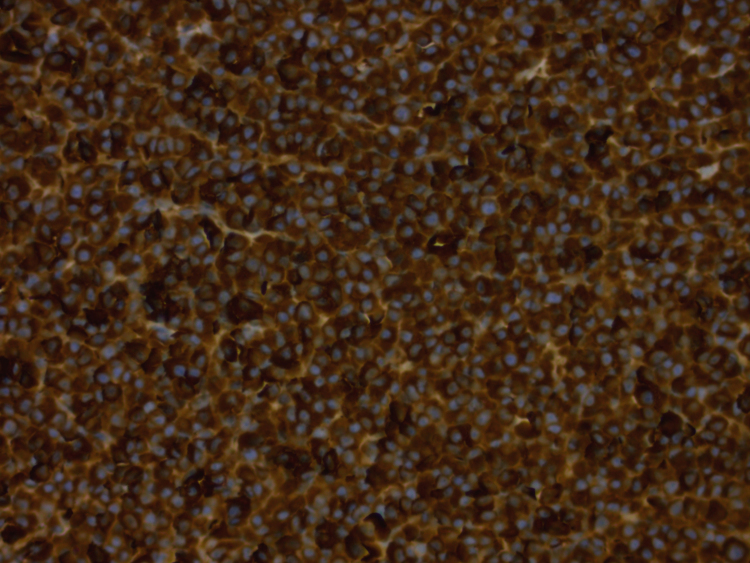

Uncemented acetabular and femoral components were used, with a ceramic-on ceramic bearing surface. Macroscopic examination of the excised femoral head confirmed a 17×13 mm2 lytic lesion in the inferior neck. Histological analysis of the femoral head showed hypercellular bone marrow with diffuse replacement of marrow spaces by a population of mature plasma cells. Occasional plasmablasts and multinucleate forms were present (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated Lambda light chain restriction (Fig. 8). In addition, scattered non-necrotising granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis were present (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Special stains for acid-fast bacilli and fungal organisms were negative.

Fig. 6.

A non-necrotising granuloma surrounded by a diffuse plasma cell infiltrate (H&E, 100× magnification).

Fig. 7.

A non-necrotising granuloma surrounded by a diffuse plasma cell infiltrate (H&E, 400× magnification).

Fig. 8.

Lambda light chain immunohistochemistry demonstrating diffuse positive cytoplasmic staining.

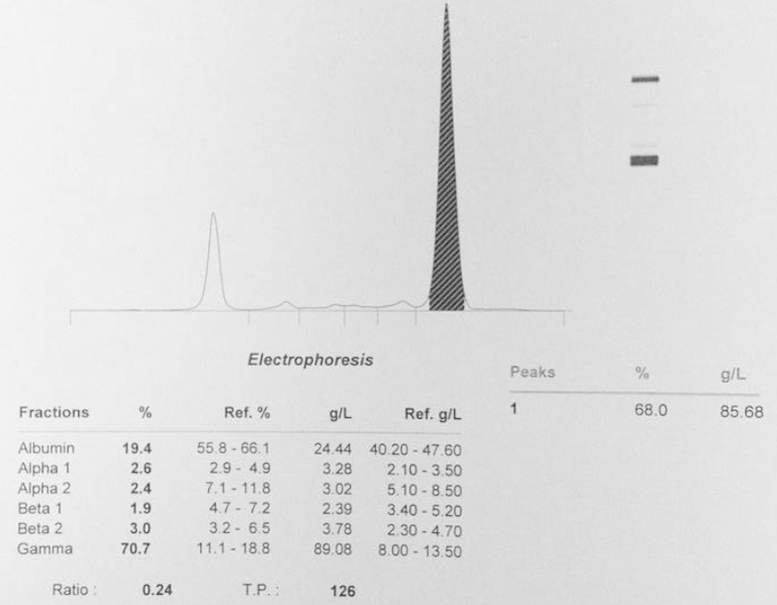

Bone marrow aspiration, biopsy and serum protein electrophoresis confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma (Fig. 9). The patient was referred to the department of haematology, where treatment with high dose dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide was started.

Fig. 9.

Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrating the IgG monoclonal peak.

At most recent follow-up 5 months post surgery the patient had an asymptomatic right hip with no change in component position (Fig. 10), and no progression of the lesions in her left hip and pelvis.

Fig. 10.

Anteroposterior radiograph of pelvis at most recent follow up.

The patient׳s clinical and biochemical response to the myeloma treatment has been good, with a drop in the IgG Lambda monoclonal peak from 80 g/l to 30 g/l. Autologous haemopoetic stem cell transplant is planned after maximal response has been achieved with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone.

2. Discussion

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disorder of unknown aetiology characterised by the presence of non-caseating granulomas, with no evidence of other known causes of granulomatous disease. It involves multiple organs, most commonly the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, and eyes, but may be present in any organ system. Involvement of the musculoskeletal system is well described in the literature. Up to 35% of patients will develop an acute or chronic polyarthropathy, and skeletal muscle granulomas occur in 80% of patients, but are largely asymptomatic. Skeletal lesions are typically bilateral and most commonly seen in the small bones of the hand and feet with associated skin lesions. Lesions of the axial skeleton and long bones are considered uncommon, and occur in approximately 5% of patients [2], [3].

Large bone lesions may be painful or asymptomatic. Neither skeletal surveys nor radio-isotope scans have proved reliable in screening for skeletal lesions [4]. The lesions are typically small cysts with minimal involvement of adjacent soft tissue, but may present as an active lytic or sclerotic lesion or pathological fracture. MRI features are of indistinct or well marginated lesions of varying sizes with decreased intensity on T1 weighted images and increased intensity on T2 and proton-density fat-saturated weighted images, and lesions may enhance after contrast [5]. There are no pathognomonic features of skeletal sarcoidosis on MRI, and the differential includes metastastatic disease, lymphoma, myeloma and disseminated tuberculosis.

Treatment of skeletal sarcoidosis is largely symptomatic. Corticosteroids have not been shown to be effective. However spontaneous resolution has been demonstrated on follow-up studies [3].

Moore et al., in a study of 40 patients with sarcoidosis and musculoskeletal symptoms, found intramedullary bone lesions on MRI in 43% of patients (17/40) [5]. The lesions ranged in size from 1 to 4 cm. Lesions of the large bones and axial skeleton were present in 33% of patients (13/40), 9 of which were multiple and 4 solitary. Two patients (5%) were coincidentally found to have MRI findings of AVN of the hip, both of whom were on corticosteroids. Less than half of the patients had biopsies of the lesions, all of which demonstrated non-caseating granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis.

The association between sarcoidosis and myeloma is poorly understood. In a review of the literature, Sen et al. identified 11 reports of patients with sarcoidosis who developed multiple myeloma [6]. The median interval from the time of diagnosis of sarcoidosis to that of multiple myeloma was 6 years which was similar to the interval of 5 years in our patient. They found that the median age at diagnosis of sarcoidosis was 56 years which was significantly older than that of the general patient population with the disease. Sarcoidosis in older age groups is associated with a chronic active clinical course. The patient in our case report was diagnosed with sarcoidosis at a more typical age of 45 years.

In a review of the literature, Brincker found 145 patients with sarcoidosis who had developed a malignant neoplasm, including 66 cases of various types of lymphoproliferative disorders [7], [8].

The observed to expected ratio of lymphoid malignancies in sarcoidosis patients was 13.2.

There is evidence that patients with sarcoidosis have immune system dysregulation, including activation of CD4-positive T-helper cells, increased secretion of cytokines, and decreased CD8-positive T-suppressor cells [9], [10]. The defective T-cell suppression and increased cytokine secretion have been postulated to result in stimulation of B cells. Hunninghake et al. showed that patients with sarcoidosis have greater ratios of IgG and IgM secreting cells compared to normal individuals [11]. They demonstrated that B lymphocytes in normal individuals, when cultured with T lymphocytes from patients with sarcoidosis, were induced to differentiate into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. The extended half-life of B lymphocytes and plasma cells in sarcoidosis patients may also increase their risk of undergoing neoplastic transformation.

In a review on skeletal sarcoidosis, Moore et al. recommended that in a patient with proven sarcoidosis, biopsy of musculoskeletal lesions detected at MRI may not be necessary [12].

However, they added that in some patients in whom sarcoidosis was not proven or a second comorbidity was suspected, a biopsy should be undertaken. This leaves the clinician with a difficult management decision. Many patients with sarcoidosis will present with anaemia and fatigue, either as a result of the primary disease or as a side effect of treatment. MRI scans and possible subsequent biopsies in all patients with sarcoidosis and musculoskeletal complaints would place a large strain on resources. We believe a high index of suspicion and good clinical judgement is required when patients with sarcoidosis present with musculoskeletal pain, and there should be a low threshold for further investigation. Serum calcium, total protein and albumin levels and possibly serum protein electrophoresis would assist in diagnosing or excluding multiple myeloma. MRI is of limited value as it does not differentiate skeletal sarcoidosis from myeloma, lymphoma, metastatic disease or disseminated tuberculosis.

3. Conclusion

We describe a patient with sarcoidosis who subsequently developed multiple myeloma to raise awareness of this association. Eleven other cases have been reported in the literature. The explanation for this association is not known, however immune dysregulation may be involved in the pathogenesis. Orthopaedic surgeons need to be aware of the association and the possibility of dual pathologies to avoid missing the diagnosis of multiple myeloma in patients with sarcoidosis. A high index of suspicion and good clinical judgement is therefore required when patients with sarcoidosis present with musculoskeletal pain, and there should be a low threshold for further investigation.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Financial remuneration

None of the authors received financial remuneration related to the subject of this article. University of Cape Town: Department of Surgery, Departmental Research Committee, Approval number 2013/069.

References

- 1.Mirels H. Metastatic disease in long bones: a proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathological fractures. Clin Orthop. 1989;249:256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick D., Niwayama G. 3rd ed. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1995. Sarcoidosis: diagnosis of bone and joint disorders; pp. 4333–4352. [Google Scholar]

- 3.University of Washington Musculoskeletal Resident Projects. Musculoskeletal manifestations of sarcoid. Roosevelt Clinic, University of Washington, 2005.

- 4.Milman N, Lund J, Graudal N, Enevoldsen H, Evald T, Nørgård P. Diagnostic value of routine radioisotope bone scanning in a series of 63 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2000;17:67–70. [PubMed]

- 5.Moore S.L., Teirstein A.E., Golimbu C. MRI of sarcoidosis patients with musculoskeletal symptoms. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:154–159. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sen F., Mann K.P., Medeiros L.J. Multiple myeloma in association with sarcoidosis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:365–368. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0365-MMIAWS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brincker H., Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247–251. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1974.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brincker H. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Chest. 1995;108:1472–1474. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vourlekis J.S., Sawyer R.T., Newman L.S. Sarcoidosis: developments in aetiology, immunology and therapeutics. Adv Intern Med. 2000;45:209–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karakantza M., Matutes E., MacLennan K., O’Connor N.T.J., Srivastava P.C., Catovsky D. Association between sarcoidosis and lymphoma revisited. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:208–212. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunninghake G.W., Crystal R.G. Mechanisms of hypergammaglobulinemia in pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:86–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI110036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore S.L., Teirstein A.E. Musculoskeletal sarcoidosis: spectrum of appearances at MR imaging. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:1389–1399. doi: 10.1148/rg.236025172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]