Abstract

Importance:

Single cigarettes, which are sold without warning labels and often evade taxes, can serve as a gateway for youth smoking. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 gives the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products, including prohibiting the sale of single cigarettes. To enforce these regulations, the FDA conducted over 335 661 inspections between 2010 and September 30, 2014, and allocated over $115 million toward state inspections contracts.

Objective:

To examine differences in single cigarette violations across states and determine if likely correlates of single cigarette sales predict single cigarette violations at the state level.

Design:

Cross-sectional study of publicly available FDA warning letters from January 1 to July 31, 2014.

Setting:

All 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Participants:

Tobacco retailer inspections conducted by FDA (n = 33 543).

Exposure(s) for Observational Studies:

State cigarette tax, youth smoking prevalence, poverty, and tobacco production.

Main Outcome(s) and Measure(s):

State proportion of FDA warning letters issued for single cigarette violations.

Results:

There are striking differences in the number of single cigarette violations found by state, with 38 states producing no warning letters for selling single cigarettes even as state policymakers developed legislation to address retailer sales of single cigarettes. The state proportion of warning letters issued for single cigarettes is not predicted by state cigarette tax, youth smoking, poverty, or tobacco production, P = .12.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Substantial, unexplained variation exists in violations of single cigarette sales among states. These data suggest the possibility of differences in implementation of FDA inspections and the need for stronger quality monitoring processes across states implementing FDA inspections.

Introduction

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) of 2009 authorizes the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products.1 Among other things, the regulations require retail stores that sell tobacco (“tobacco retailers”) to ensure that tobacco products are inaccessible to children and youth and restrict the sale of single cigarettes, or “loosies.”1 Despite these regulations, the sale of single cigarettes remains a problematic issue in many states and some are pursuing legislation above and beyond the FSPTCA to address their sale.2,3 Though single cigarettes are also commonly sold on the street by individuals as a way to generate income,4–6 for the purposes of this study we only focused on retailer sales as they are subject to FSPTCA regulations.

High availability of single cigarettes likely promotes smoking and undermines quit attempts, though some evidence suggests that existing smokers may use singles to try to cut down on smoking.7–9 Single cigarette sales often avoid taxes, and their lower up-front cost can make them more attractive to youth.10 Sale of single cigarettes is more common in neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic status and more racial/ethnic minority residents.10,11 Historically, retailers have been more willing to sell single cigarettes to racial/ethnic minority youth.12 Landrine et al. found in the early 1990s that 39% of stores sold single cigarettes to youth in middle-class California cities12; more recently, however, researchers in Ohio and North Carolina found that virtually no tobacco retailers advertised single cigarette sales in 2010 and 2011, respectively.13,14 It is likely that as the ban on single cigarettes has become more widely known, retailers have become less forthcoming about their sale. This was the case for a tobacco retailer education intervention conducted in California; paid research staff conducted undercover buys of single cigarettes before and after an educational intervention with tobacco retailers. Prior to intervention, 68% of retailers who sold singles kept them behind the counter, while 100% of retailers selling singles kept them behind the counter post-intervention.15

With over 374 500 tobacco retailers in the United States,16 enforcement of the FSPTCA’s ban on the sale of single cigarettes is relevant to addressing youth smoking as well as health disparities. Limited data exist to describe the phenomenon of single cigarette sales among tobacco retailers; much of the literature available presents information from street sales and from inner cities,4,6,17 and data are not comparable across studies. To address this gap in the literature, we sought to examine national FDA inspection data for violations concerning the sale of single cigarettes by retailers and to identify predictors of differences in proportions of these violations by state.

Methods

The routine inspection of tobacco retailers is managed by the FDA and subcontracted to each state, often to a state agency. The FDA requires state contractors to conduct two types of inspections: one with youth purchase attempts known as Undercover Buy inspections and one conducted solely by adult inspectors, known as Advertising and Labeling (A&L) inspections.18 For the purposes of this article we only used data from A&L inspections, as those inspections send an FDA-credentialed adult to inspect tobacco retail stores for compliance with FDA regulations, among which the sale of single cigarettes is a violation. The FDA does not release the inspection protocol, though it is known that during the inspection of a tobacco retailer, inspectors have the authority to visually scan the store, including parts not accessible to customers, for evidence of violations and interview store employees.19 If a retailer is found to be in violation of a provision of the FSPTCA, the retailer receives a warning letter in the mail that indicates the date of the inspection, the violation(s) observed during the inspection, and instructions for responding to the FDA with a plan for correcting the violation. These warning letters contain standard language for different types of inspections. No information is available about state enforcement (which cannot be funded by the FDA and is separate from FDA enforcement).18 Retailers have 15 days to respond to the letter. Once a tobacco retailer receives a warning letter, the FDA conducts a follow-up inspection. If the retailer is still found to be in violation of the FSPTCA, the FDA may choose to administer a civil money penalty, or produce a no-tobacco-sale order.

We examined publicly available warning letters that were posted on the FDA Compliance Inspections website by September 2, 2014,20 resulting from FDA inspections for compliance with provisions of the FSPTCA from January 1, 2014 to July 31, 2014, notifying retailers in the 50 US states and District of Columbia of violations. These data constitute approximately 10% of all FDA inspections.

The FDA does not release specific sampling strategies for each state, and some states choose to oversample in areas with high proportions of racial/ethnic diversity, low-socioeconomic residents, and near schools; therefore, violation rates are not comparable across states. Thus, we compare the proportion of violations found during A&L inspections for state variation in order to assess both compliance with FSTPCA regulations and state implementation of compliance enforcement.

To see if the proportion of violations could be predicted by state-level characteristics, we used Spearman rank-sum correlations and linear regression. We considered four possible explanations for single cigarettes sales. Single cigarette sales may be driven by demand from people with limited resources for purchasing full packs of cigarettes. We thus assessed the role of (1) state youth smoking prevalence21 and (2) the percentage of people living in poverty.22 Because single cigarettes may be sold to evade taxes, we assessed the role of (3) state cigarette excise tax.23 Lastly, we thought historically tobacco-producing states may be more lenient towards the sale of single cigarettes; we thus assessed the role of (4) being a historically tobacco-producing state (GA, KY, NC, SC, TN, VA), as defined by Thrasher et al.24 We used two-tailed tests and a significance threshold of P < .05. To provide a visual representation of the heterogeneity of inspections, warning letters, and single cigarette violations across states, we geocoded25 each inspection to the street address listed in the letter and mapped these locations using QGIS 2.2 (www.qgis.org).

To ensure the reliability of our data, one author (HMB) coded each letter for type of violation reported, and a second author (JGLL) coded 10% of the letters, finding no discrepancies. Data used in this study were obtained from a publicly available data set and no human subjects were involved, therefore IRB approval was not sought.

Results

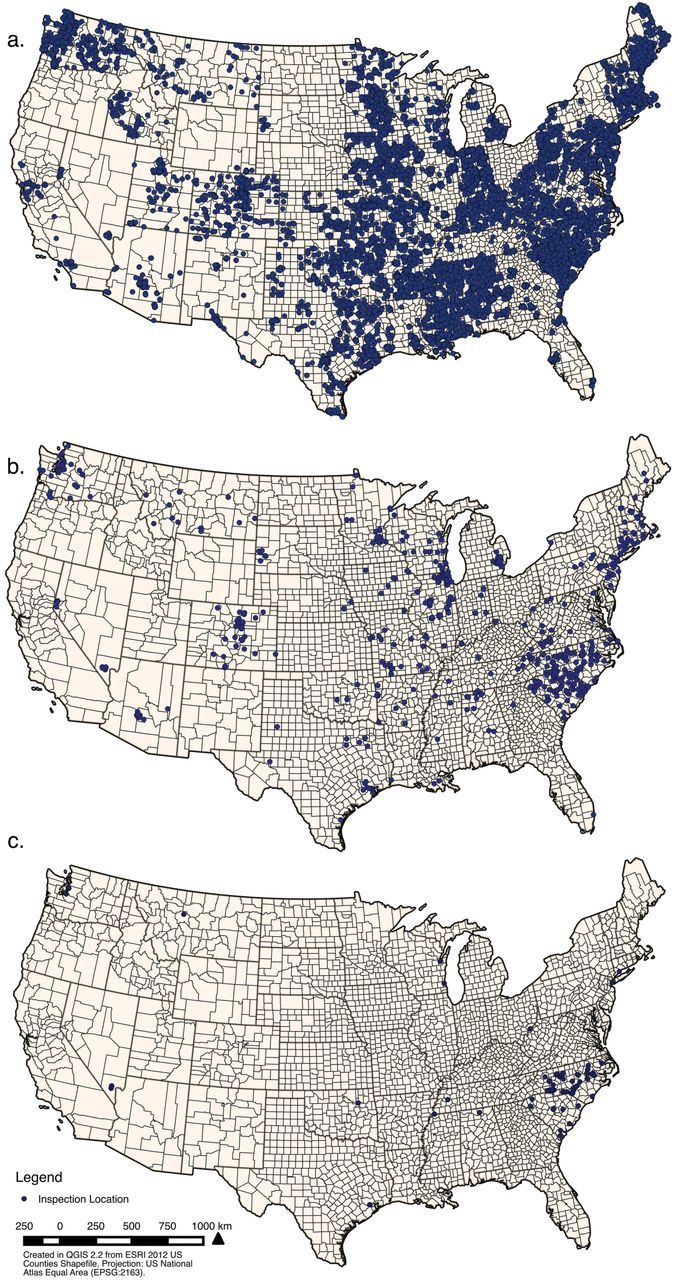

During the 7-month time period, FDA’s contractors completed a total of 33 543 A&L inspections in 49 states and the District of Columbia (Figure 1a). Thirty-nine states issued one or more warning letters in the time period analyzed, indicating that 2.1% of inspections (n = 718) resulted in a warning letter (Figure 1b). Warning letters were not proportionally distributed across states; 12 states had zero violations while one state (North Carolina) had 107 (Table 1) (M = 15.3, SD = 24.7). Other states with relatively high numbers of warning letters were Colorado (n = 41), Illinois (n = 80), Michigan (n = 48), South Carolina (n = 90), and Washington (n = 52). Finally, of all warning letters issued, 13.6% included a violation for single cigarette sales (Figure 1c). Numbers of warning letters for single cigarettes varied greatly across states: 38 states produced no warning letters for selling single cigarettes, while one state, North Carolina, produced 64, the highest of any state (M = 6.3, SD = 12.5).

Figure 1.

(a) Location of inspections, (b) location of warning letters by state, and (c) location of warning letters for single cigarette violations, January–July 2014.

Table 1.

State Warning Letters for Single Cigarette Violations, n = 718, January 1–July 31, 2014

| State A&L totals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Inspections | Warning letters | Singles (n, % of warning letters) |

| AL | 1411 | 12 | 1, 8% |

| AK | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| AZ | 154 | 11 | 0 |

| AR | 1022 | 11 | 0 |

| CA | 157 | 0 | 0 |

| CO | 739 | 41 | 0 |

| CT | 39 | 19 | 1, 5% |

| DE | 250 | 0 | 0 |

| DC | 71 | 0 | 0 |

| FL | 147 | 1 | 0 |

| GA | 343 | 1 | 0 |

| HI | 56 | 0 | 0 |

| ID | 310 | 0 | 0 |

| IL | 715 | 80 | 0 |

| IN | 2515 | 8 | 0 |

| IA | 822 | 9 | 0 |

| KS | 839 | 1 | 0 |

| KY | 668 | 2 | 0 |

| LA | 669 | 2 | 0 |

| ME | 1315 | 3 | 0 |

| MD | 137 | 1 | 0 |

| MA | 1414 | 5 | 0 |

| MI | 395 | 48 | 0 |

| MN | 1253 | 24 | 0 |

| MS | 1513 | 2 | 0 |

| MO | 657 | 24 | 0 |

| MT | 154 | 11 | 1, 9% |

| NE | 33 | 3 | 0 |

| NV | 75 | 17 | 5, 29% |

| NH | 92 | 12 | 0 |

| NJ | 515 | 14 | 0 |

| NM | 114 | 0 | 0 |

| NY | 246 | 6 | 2, 33% |

| NC | 1387 | 107 | 64, 60% |

| ND | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OH | 91 | 0 | 0 |

| OK | 512 | 3 | 1, 33% |

| OR | 57 | 1 | 0 |

| PA | 1982 | 13 | 0 |

| RI | 305 | 2 | 0 |

| SC | 3817 | 90 | 9, 10% |

| SD | 31 | 9 | 0 |

| TN | 167 | 10 | 2, 20% |

| TX | 1765 | 18 | 3, 17% |

| UT | 247 | 0 | 0 |

| VT | 67 | 0 | 0 |

| VA | 651 | 13 | 0 |

| WA | 2816 | 52 | 5, 10% |

| WV | 537 | 8 | 1, 13% |

| WI | 170 | 24 | 3, 13% |

| WY | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 33 543 | 718 | 98, 13.6% |

To test if the proportion of warning letters issued for single cigarettes could be predicted by four factors, we first assessed bivariate correlations with youth smoking prevalence (r s = 0.10, P = .47), poverty (r s = 0.21, P = .14), state cigarette excise tax (r s = −0.05, P = .73), and being a tobacco-producing state (r s = 0.23, P = .10). None achieved statistical significance. We then ran a linear regression model containing all of these variables at the state level. This, too, did not achieve statistical significance, R 2 = 0.14, F(4,50) = 1.93, P = .12.

Lastly, by mapping each inspection, warning letter, and single cigarette violation, we provide a visual illustration of the variation that existed in inspections and violations across states. The map indicated substantive variation in the number of inspections conducted in states, in the number of violations identified, and in the location of single cigarette violations. Inspections tended to be clustered towards the east coast (California is noticeably absent), and warning letters as well as single cigarette sale violations were primarily clustered in North and South Carolina (Figure 1, a–c).

Discussion

Principal Findings

Tobacco retailer inspections under the FSPTCA produce striking variation in the proportion of warning letters for single cigarette sales. One state, North Carolina, had a substantially higher percentage of warning letters issued for single cigarette violations. These differences could not be predicted at the state level by known or suspected correlates of single cigarette sales (ie, youth smoking rate, percent poverty rate, excise taxes, or being a tobacco producing state). Moreover, reports of retailer single cigarette sales as a problem in the media do not seem to parallel FDA inspection results. Lawmakers in Michigan, for example, have identified retailer single cigarette sales as a problem and are pursuing legislation.3 In addition, Detroit’s police chief has asked retailers to address the sale of singles26; yet, Michigan shows no warning letters for single cigarettes out of 395 statewide inspections (Table 1). Researchers provide evidence for the availability of single cigarettes at retailers in Baltimore6,8; this, too, is not reflected in FDA violations. Similar inconsistencies appear in other states.27,28 We know of no evidence that tobacco retailer violations should vary so extremely between states. Synar Amendment reports, for example, show less extreme differences in youth purchase rates between states than we have identified.29 Were retailers equally likely to violate the FSPTCA across states, our data indicate there may be problematic differences in the implementation of compliance efforts by state agencies on behalf of the FDA.

These discrepancies indicate that states may not be fully leveraging the FDA’s A&L inspections to promote retailer compliance with legislation and maximize public health protection. Previous research shows wide variation in state implementation of (and resistance to) federal inspection programs.30,31 We suggest that it is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that, based on FDA inspections data presented in this paper, similar variation is occurring in FDA’s current inspections program. This notion is further supported by our results showing that certain characteristics, which we posited to be associated with single cigarette sales, were not predictive of violations according to warning letters sent by the FDA inspections programs. In response to these data, efforts to assess the quality of state implementation of A&L inspections is likely needed to augment current FDA enforcement resources.

Strengths and Limitations

This article is not without limitations. First, neither our study design nor the available data permit us to causally infer the reasons for state-level differences. Second, state contracts with the FDA may lapse or not be in place during different periods of the year. Third, while we use the proportion of violations instead of the violation rate, our research would be stronger if inspections had known sampling weights. Fourth, the data analyzed only includes retailer sales of single cigarettes, which account for only a portion of the single cigarettes available; single cigarettes are also available on the streets through informal means, where individuals will sell single cigarettes as a strategy for generating income.4–6 However, there are several strengths. We used national data from over 33 000 inspections conducted in 49 states and the District of Columbia and data come from a formalized inspections protocol implemented by FDA Officers that allows for inspections of areas of retailers not accessible to the public (or to researchers).

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

Future research should assess the reasons for differences in single cigarette sales violations of FSPTCA. It is plausible that the composition of retailers, differences in retailer trade group training, and differences in state-level retailer education may be partially responsible for these differences. Additional programmatic reasons could account for differences, including characteristics of FDA inspectors, inspection sampling strategies, and inspector quality improvement protocols. However, we remain concerned that unexplained variation in rates of single cigarette warning letters may also suggest that there are differences in the way inspection protocols are implemented regarding single cigarette sales.

Conclusion

To ensure compliance with the FSPTCA, the FDA invests significant resources in tobacco retailer inspections, having conducted over 335 661 inspections between June 2010 and September 2014, and allocating over $115 million toward state inspections contracts.20,32 Unfortunately, despite the policy change and economic resources committed to enforcing it, substantial, unexplained variation exists in inspections by state, particularly violations of single cigarette sales. These data suggest the possibility of differences in implementation of FDA inspections between states and the need for stronger quality monitoring processes across states implementing FDA inspections. Given the large investment in these inspections and the important role they play in reducing tobacco use at a population level, further investigation is needed to identify ways to optimize state tobacco retailer inspections, thereby maximizing the health impact of these regulations and policies at the population level.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by grant number F31CA186434 from the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health and in part by grant number 1P50CA18090701 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). JGLL effort on this publication was funded in part by the UNC TCORS trainee fellowship under grant number 1P50CA18090701; he conducted data analyses and assisted with manuscript development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Declaration of Interests

The authors are commissioned as FDA officers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Food & Drug Administration. The FDA’s inspection program did not fund this research. JGLL has a royalty interest in a store audit/compliance and mapping system, Counter Tools ( http://countertools.org ), owned by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The tools and audit mapping system were not used in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jennifer Greyber for assisting in the editing and submission of this manuscript and Shyanika W. Rose for her knowledge of the literature.

References

- 1. Food and Drug Administration. Overview of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act: Consumer Fact Sheet 2015. www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/ucm246129.htm Accessed November 17, 2014.

- 2. Martin T. Michigan tobacco tax inspections yield illegal smokes—along with shoes, DVDs, contacts. MLive. 2013. www.mlive.com/news/index.ssf/2013/03/tobacco_tax_michigan_enforceme.html Accessed November 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oosting J. “Loosie” Lockdown? Michigan lawmaker seeks new penalties for selling, buying single cigarettes. MLive. 2014. www.mlive.com/lansing-news/index.ssf/2014/09/loosie_lockdown_michigan_lawma.html Accessed November 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Latkin CA, Murray LI, Clegg Smith K, Cohen JE, Knowlton AR. The prevalence and correlates of single cigarette selling among urban disadvantaged drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):466–470. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldstein J. On Manhattan Streets, Loosie Men Sell Illegal Smokes. The New York Times. April 4, 2011. www.nytimes.com/2011/04/05/nyregion/05loosie.html Accessed November 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stillman FA, Bone LR, Milam AJ, Ma J, Hoke K. Out of view but in plain sight: the illegal sale of single cigarettes. J Urban Health. 2014;91(2):355–365. 10.1007/511524-013-9854-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall MG, Fleischer NL, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Arillo-Santillan E, Thrasher JF. Increasing availability and consumption of single cigarettes: trends and implications for smoking cessation from the ITC Mexico Survey [published online ahead of print September 5, 2014]. Tob Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith KC, Stillman F, Bone L, et al. Buying and selling “loosies” in Baltimore: the informal exchange of cigarettes in the community context. J Urban Health. 2007;84(4):494–507. 10.1007/s11524-007-9189-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Barnoya J, Sansores R, O’Connor R. Consumption of single cigarettes and quitting behavior: a longitudinal analysis of Mexican smokers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):134 www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/134 Accessed February 3, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Archbald C. Sale of individual cigarettes: a new development. Pediatrics. 1993;91(4):851 http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/91/4/851.1.short Accessed November 17, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klonoff EA, Fritz JM, Landrine H, Riddle RW, Tully-Payne L. The problem and sociocultural context of single-cigarette sales. JAMA. 1994;271(8):618–620. 10.1001/jama.1994.03510320058030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Alcaraz R. Minors’ access to single cigarettes in California. Prev Med. 1998;27(4):503–505. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frick RG, Klein EG, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Tobacco advertising and sales practices in licensed retail outlets after the Food and Drug Administration regulations. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):963–967. 10.1007/s10900-011-9532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rose SW, Myers AE, D’Angelo H, Ribisl KM. Retailer adherence to Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, North Carolina, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10120184. 10.5888/pcd10.120184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woodruff SI, Wildey MB, Conway TL, Clapp EJ. Effect of a brief retailer intervention to reduce the sale of single cigarettes. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(3):172–174. dx.doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-9.3.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Report to the Nation: The Tobacco Retail and Policy Landscape. 2014. http://cphss.wustl.edu/Products/Documents/ASPiRE_2014_ReportToTheNation.pdf Accessed November 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stillman FA, Bone L, Avila-Tang E, et al. Barriers to smoking cessation in inner-city African American young adults. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1405–1408. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. General Services Administration. FDA Tobacco Retail Inspections. 2013. www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&id=ed3cf6b75ec881cbc0270f86908b4c29&tab=core&_cview=1. Accessed January 23, 2015.

- 19. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. 2009. Pub 1. L No.111-31. [Google Scholar]

- 20. US Food and Drug Administration. Compliance Check Inspections of Tobacco Product Retailers 2014. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/oce/inspections/oce_insp_searching.cfm Accessed September 2, 2014.

- 21. Schmidt L. Key State-Specific Tobacco-Related Data and Rankings. Washington, DC: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; 2014:2002 www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0176.pdf Accessed November 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Social Explorer. American Community Survey 2011 to 2013 (3-Year Estimates). 2014. www.socialexplorer.com/tables/ACS2013_3yr/R10835585. Accessed November 13, 2014.

- 23. Federation of Tax Administrators. State Excise Tax Rates on Cigarettes, January 2, 2014. Washington, DC: Federation of Tax Administrators; 2014. www.taxadmin.org/fta/rate/cigarette.pdf Accessed November 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thrasher JF, Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Ribisl KM, Haviland ML. The impact of anti-tobacco industry prevention messages in tobacco producing regions: evidence from the US truth campaign. Tob Control. 2004;13(3):283–288. 10.1136/tc.2003.006403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Texas A&M Geoservices. Geocoding Services 2014. http://geoservices.tamu.edu/Services/Geocode/ Accessed September 24, 2014.

- 26. Harb A. Detroit police chief addresses crime, safety issues with business owners. The Arab American News. 2013. www.arabamericannews.com/news/news/id_7555 Accessed November 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Chicago Lampoon. Chicago’s Growing Cigarette Black Market: Cook Co. Raises Cig Taxes Again. 2013. http://chicagolampoon.blogspot.com/2013/03/chicagos-growing-cigarette-black-market.html Accessed November 14, 2014.

- 28. Public Health Management Corporation. Underage, Undercover: Teen Workers Help Identify Merchants Selling Tobacco to Teens. Philadelphia, PA: Public Health Management Corporation; 2014. www.phmc.org/site/publications/directions-archive/directions-spring-2011/588-underage-undercover-teen-workers-help-identify-merchants-selling-tobacco-to-youth Accessed November 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. FFY 2012 Annual Synar Reports: Tobacco Sales to Youth. n.d. www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed November 21, 2013.

- 30. DiFranza JR. Best practices for enforcing state laws prohibiting the sale of tobacco to minors. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;11(6):559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DiFranza JR, Dussault GF. The federal initiative to halt the sale of tobacco to children—the Synar Amendment, 1992–2000: lessons learned. Tob Control. 2005;14(2):93–98. http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/14/2/93.short Accessed November 25, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Tobacco Retail Inspection Contracts 2014. www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/ResourcesforYou/ucm228914.htm Accessed September 2, 2014.