Abstract

Background

Empty sella (ES) has been regarded as an incidental finding. Recently, there have been studies documenting association of ES with hormonal and non-hormonal abnormalities. To detect the prevalence of empty sella in routine MRI brain study and to find associations with other diseases.

Methods

A retrospective study was carried out for patients undergoing MRI brain studies in the radiology department of a teaching institution. Patients with ES formed the study group. The rest formed the baseline population. Presence of nine select variables, viz. hormonal disturbances, headache, sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, vertigo, psychiatric disorders, visual disturbances, ataxia and raised intracranial tension, was analyzed amongst the study group, as well as the baseline population. Association of ES and the select variables was analyzed by determining means and proportions and using Chi-square test.

Results

During the study period, a total of 12,414 patients underwent MRI brain studies at our centre. ES was found in 241 (1.94%) patients. The proportion of patients in the ES and non-empty sella groups for each of the variables were as follows: hormonal disturbances (3.31% vs 0.56%, P = .000), headache (8.3% vs 7.4%, P = .596), SNHL (3.7% vs 1.3%, P = .0010), seizure (6.2% vs 13%, P = .002), vertigo (4.6% vs 1.6%, P = .000), psychiatric disorders (4.6% vs 1.3%, P = .000), visual disturbances (2% vs 1.1%, P = .166), ataxia (1.7% vs 1.2%, P = .519) and raised ICT (2% vs 0.5%, P = .002).

Conclusion

Hormonal disturbances, psychiatric disorders, raised ICT and SNHL have been found to be more often associated with ES as compared to general population.

Keywords: Empty sella, MRI, Brain

Introduction

Empty sella (ES) is a condition where the sella turcica (ST) is partially or completely filled with cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) and the pituitary gland is compressed against the sellar wall with or without enlargement of the ST. Since its initial descriptions in post-mortem studies and radiographs, the condition is being increasingly recognized in day-to-day radiology practice due to the advent of MRI. ES with a normal-sized ST, detected during MRI study of the brain, is often disregarded as an incidental finding without giving any clinical significance. However, since its initial description, various endocrine as well as non-endocrine abnormalities have been described in association with ES.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Although various associations have been described with ES, the exact significance is not clear. ST and pituitary gland are well visualized in MRI, particularly in sagittal and coronal planes. For a long time since now, it has been a routine practice in most imaging centres and institutes including ours to assess the ST and pituitary gland during MRI study of the brain and comment on it as a part of brain reporting protocol. In this single-centre cross-sectional analysis with retrospective data collection, we have evaluated various associations of ES in patients who have undergone MRI brain for a variety of clinical conditions.

Materials and methods

Setting

The study was conducted at the department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging of a tertiary care hospital and teaching institution.

Study population

The study population consisted of all patients who underwent MRI of brain for various indications at the MRI centre of our institute from April 2006 to March 2015. Patients who were diagnosed to have ES in the MRI report formed the study group.

Exclusion criteria

(1) MRI reports that did not mention about the pituitary gland, (2) Patients of pituitary gland tumours or surgery, (3) MRI reports without any clinical details.

Data acquisition

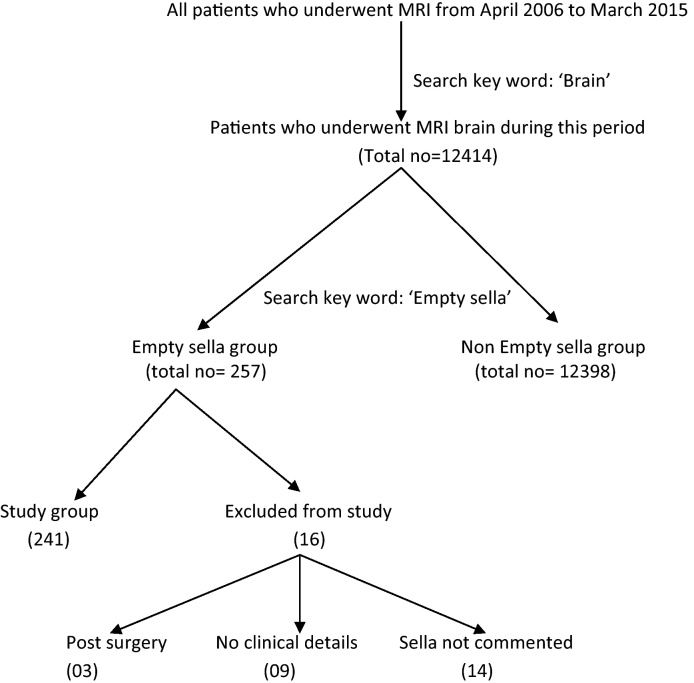

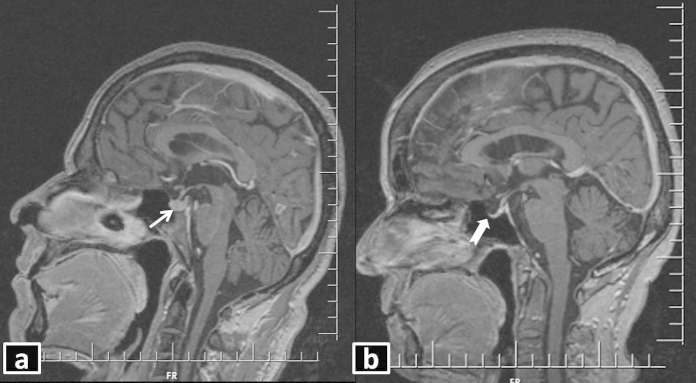

All brain MRI reports in the study period were first identified by searching in the MRI report database with the keyword ‘brain’ (Fig. 1). These patients formed the baseline population. A further search was made with the keyword ‘empty sella’. Patients having MRI reports with mention of ‘empty sella’ formed the study group. Standard criteria (CSF occupying more than 50% of ST with compressed pituitary gland against the sellar wall) for MRI diagnosis of ES are followed at our institute (Fig. 2). Clinical details/diagnosis/condition mentioned in the MRI report, as documented at the time of filling up the MRI report template was recorded. Based on the available literature and our experience, presence of nine select variables (viz., hormonal disturbances, headache, sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, vertigo, psychiatric disorders, visual disturbances, ataxia and raised intracranial tension) was noted amongst baseline population as well as the study group.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing selection of patients with empty sella for the study.

Fig. 2.

T1WI sagittal post-contrast MRI demonstrating (a) normal pituitary gland and stalk (white arrow), (b) empty sella (white block arrow). Note that most of the sella turcica is occupied by cerebrospinal fluid, which appears hypointense.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the data using Statistical packages for social sciences 22 determining the means and proportions. Further, Chi-square test was used to compute the association between select variables and ES.

Informed consent

We obtained necessary institutional Ethical committee waiver for the secondary data. Permission from the institution was also obtained for analyzing the data. At no juncture did we attempt to identify any patient of ES.

Results

During the study period, ranging from 01 April 2006 to 31 March 2015, a total of 12,414 patients underwent MRI of brain for various indications. Based on the MRI reports, ES was found in 241 (1.94%) (Fig. 1). Age and sex distribution of the study group are shown in Table 1. One hundred and ten (45.6%) patients (in both sexes) belonged to the 30–50 years age group. Males (139, 57.7%) dominated the list of patients having ES, although statistically the prevalence was noted to be nearly four times more in females when corrected for total number of male and female patients in the whole study population. 95% CI for difference in proportion of ES between males and females was 95% CI = (.013–.040) ± 1.96x·0078 = (−.0448, −.0292) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of study group.

| S. No. | Age (years) | Males | Females | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | <30 | 14 (10.1%) | 09 (8.9%) | 23 |

| 2. | 30–50 | 69 (49.6%) | 41 (40.2%) | 110 |

| 3. | >50 | 56 (40.3%) | 52 (50.9%) | 108 |

| Total | 139 | 102 | 241 |

Table 2.

Prevalence of empty sella between male and female patients.

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Study population | 9982 | 2516 |

| Study group (ESS) | 139 | 102 |

| Actual prevalence of empty sella study population | 1.39/1000 males | 4.05/1000 females |

We further did exploratory analysis of the available data. The prevalence of nine select variables (viz., hormonal disturbances, headache, sensorineural hearing loss – SNHL, seizures, vertigo, psychiatric disorders, visual disturbances, raised intracranial tension ICT and ataxia), amongst both the categories (study group as well as total study population), is given (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of nine select variables in empty sella and non-empty sella group.

| S. No. | Variable | ESS (n = 241) | Non-ESS (n = 12,398) | Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hormonal disturbances | 08 (3.3%) | 69 (0.56%) | 33.901 | .000 |

| 2 | Headache | 20 (8.3%) | 919 (7.4%) | .281 | .596 |

| 3 | SNHL | 09 (3.7%) | 161 (1.3%) | 11.377 | .001 |

| 4 | Seizures | 15 (6.2%) | 1614 (13%) | 10.019 | .002 |

| 5 | Vertigo | 11 (4.6%) | 204 (1.6%) | 12.939 | .000 |

| 6 | Psychiatric disorders | 11 (4.6%) | 167 (1.3%) | 19.149 | .000 |

| 7 | Visual disturbances | 05 (2%) | 141 (1.1%) | 1.921 | .166 |

| 8 | Ataxia | 04 (1.7%) | 150 (1.2%) | .416 | .519 |

| 9 | Raised ICT | 05 (2%) | 70 (0.5%) | 9.983 | .002 |

Hormonal disturbances

[08/241, 69/12,398 (P = .000)]: It was observed that 3.31% of cases with ES suffered from hormonal disturbances as compared to 0.56% of cases in the total study population. A clear association was observed between cases with ES and those suffering from hormonal disturbances (P = .000). Various types of hormonal disturbances observed in the ESS group are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distribution of cases of hormonal disturbances.

| S. No. | Hormonal disturbance | ESS | Total cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panhypopituitarism | 01 | 04 |

| 2 | Acromegaly | 01 | 30 |

| 3 | Amenorrhoea with galactorrhoea | 02 | 18 |

| 4 | Growth hormone deficiency | 01 | 03 |

| 5 | Short stature | 02 | 09 |

| 6 | Hypogonadotropic gonadism | 01 | 05 |

| Total | 08 | 69 | |

Headache

[20/241, 919/12,398 (P = .596)]: Around 8.3% of cases in study group (target population) and 7.4% of cases in study population had suffered from headache, respectively; although a clear association of headache with ES could not be established.

SNHL

[09/241, 161/12,398 (P = .0010)]: A strong association was found to exist between ES and SNHL, as seen in the study group where 3.7% cases had SNHL, which is much higher as compared to 1.3% cases found in the total study population

Seizure

[15/241, 1614/12,398 (P = .002)]: Cases suffering from seizure were more in both the groups with nearly 6.2% in the study group and 13% cases in study population experienced seizures. Nine out of fifteen patients had generalized tonic–clonic variety of seizure. Three patients had complex partial seizure and subtype was not mentioned in the reports of the three cases amongst the study group cases. A strong association was found to exist between ES and seizure.

Vertigo

[11/241, 204/12,398 (P = .000)]: It was found to have a strong association with ES and was higher among cases having ES with nearly 4.6% cases suffering with it as compared to the total study population where only 1.6% cases were observed.

Psychiatric disorders

[11/241, 167/12,398 (P = .000)]: A clear association was also found between psychiatric disorders and ES, where cases suffering with psychiatric disorders were much higher in the study group with nearly 4.6% as compared to the study population with only 1.3%. The spectrum of psychiatric disorders, which were noted in our study group, is schizophrenia (three), behavioural disturbances (four), depression (two), delusion disorder (one) and bipolar disorder (one).

Visual disturbances

[5/241, 141/12,398 (P = .166)]: Study group with ES did not show any statistical association with cases suffering from visual disturbance. Visual disturbances in the study group included sudden painless loss of vision in both eyes in two patients, unilateral vision loss in one patient, and blurring of vision in two patients.

Ataxia

[4/241, 150/12,398 (P = .519)]: 1.7% patients in the study group and 1.2% in the total study population had ataxia. The association was not found to be statistically significant.

Raised ICT

[5/241, 70/12,398 (P = .002)]: Around 2% cases among study group and 0.5% in study population suffered from raised ICT which was found to be statistically significant.

Discussion

ES is considered a common finding in imaging studies of the brain with a widely varying reported prevalence of 8–38%.7, 8 ES is considered primary, when there is no history of any intervention (surgical/pharmacological or others) in the sellar region. Although the exact pathogenesis of primary ES is not known, it is postulated that a congenital defect/weakness in the diaphragm sellae coupled with CSF pulsation plays a major role. With ever-increasing number of patients undergoing CT scan and MRI studies of brain, the reported prevalence of ES is set to rise proportionately. The prevalence of ES in our study is 1.94%, which is quite low as compared to the rest of the previous studies. One reason for such low prevalence could be the standard MRI criteria used (i.e. more than 50% of ST being occupied by CSF) for diagnosis of ES at our institute. Another reason could be that some of the cases of ES were not mentioned in the report as were considered normal variation by the interpreting radiologist, although it is a practice in our institute to report all such cases. Most of the previous studies on ES have been case reports, case series and a few original articles with relatively small study population. As our baseline study population is substantially large, it is likely that the prevalence of ES noted in our study is a true reflection amongst the general population. In any case, the prevalence is unlikely to be as high as is reported in many previous studies.

Although males dominated the list of ES patients in the study group, true incidence of ES was found to be nearly four times more common in females when corrected for the total population echoing similar results as published earlier.

The reported peak age prevalence of ES is sixth decade.7 Interestingly, 55% of our patients of ES were less than 50 years of age. In males, the prevalence of ES was found more commonly in 30–50 years group (49% vs 40%) as compared with females, where it was more in the >50 years group (40% vs 50%). Such a variation in the prevalence of ES with respect to age group and sex has not been reported previously. It is expected that with increasing use of MRI studies of the brain, prevalence of ES in younger population is set to increase.

Many previous studies have focused on the endocrine abnormalities in ES and found a strong correlation with the same.2, 3, 4 We also found a clear association of ES with hormonal disturbances. A variety of hormonal disturbances were noted in patients of ES (Table 4), although individually no specific diagnosis was prevalent. Although many previous studies have found association of headache and visual disturbances with ES,3, 9, 10, 11 our study did not find a significant correlation as compared with the baseline population. Similarly, we did not find any correlation of ataxia with ES.

Association of ES and psychiatric ailments has not been described widely.9 Our study found a strong correlation with psychiatric disorders, although individually there was no specific predilection for any particular type of psychiatric disorder. As reported earlier,10, 12 the present study also found a strong correlation of ES with raised ICT. We also found a strong association of ES with SNHL, which has not been reported earlier. Vertigo demonstrated a weak correlation with ES.

To the best of our knowledge, no such studies have been reported with such a large patient database with the variables as described in our study. However, the study suffers from inherent limitations of retrospective data collection and analysis based on patients’ database maintained in the MRI centre, although precautions were taken to incorporate all relevant data based on the search keywords. Also the investigators based their findings solely on the patient details available in the MRI report, which is assumed to be correct and relevant as entered by the resident working in the MRI centre at that point of time. Selection bias, although less likely, cannot be entirely ruled out. As mentioned earlier, hormonal profile for most of the patients was not available to comment on, as the study was focused on retrospective analysis of MRI reports only.

Conclusion

ES need not always be an incidental finding on imaging. Certain clinical conditions like hormonal disturbances, psychiatric disorders, raised ICT and SNHL have been found to be more often associated with ES as compared to general population. We did not find any significant correlation of ES with headache and visual disturbances as opposed to many previous studies.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Davis S., Tress B., King J. Primary empty sella syndrome and benign intracranial hypertension. Clin Exp Neurol. 1978;15:248–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Monte P., Foppiani L., Cafferata C., Marugo A., Bernasconi D. Primary “empty sella” in adults: endocrine findings. Endocr J. 2006;53(6):803–809. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k06-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghatnatti V., Sarma D., Saikia U. Empty sella syndrome – beyond being an incidental finding. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl. 2):S321–S323. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.104075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rani P.R., Maheshwari R., Reddy T.S., Prasad N.R., Reddy P.A. Study of prevalence of endocrine abnormalities in primary empty sella. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(Suppl. 1):S125–S126. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.119527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zagardo M.T., Cail W.S., Kelman S.E., Rothman M.I. Reversible empty sella in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: an indicator of successful therapy? Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17(10):1953–1956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J.H., Ko J.H., Kim H.W., Ha H.G., Jung C.K. Analysis of empty sella secondary to the brain tumors. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46(4):355–359. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.46.4.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Marinis L., Bonadonna S., Bianchi A., Maira G., Giustina A. Primary empty sella. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5471–5477. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foresti M., Guidali A., Susanna P. Primary empty sella. Incidence in 500 asymptomatic subjects examined with magnetic resonance. Radiol Med. 1991;81(6):803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianconcini G., Bragagni G., Bianconcini M. Primary empty sella syndrome. Observations on 71 cases. Recenti Prog Med. 1999;90(2):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saindane A.M., Lim P.P., Aiken A., Chen Z., Hudgins P.A. Factors determining the clinical significance of an “empty” sella turcica. Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(5):1125–1131. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallardo E., Schächter D., Cáceres E. The empty sella: results of treatment in 76 successive cases and high frequency of endocrine and neurological disturbances. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1992;37(6):529–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maira G., Anile C., Mangiola A. Primary empty sella syndrome in a series of 142 patients. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(5):831–836. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.5.0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]