Abstract

Objective: To investigate the role of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in hypoxia-induced gastric cancer (GC) metastasis and invasion. Methods: We investigated the differentially expressed lncRNAs resulting from hypoxia-induced GC and normoxia conditions using microarrays and validated our results through real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The role of the targeting lncRNA was further detected by in vivo and in vitro assays. Results: We found an lncRNA, AK123072, which was up-regulated by hypoxia. AK123072 was frequently up-regulated in GC samples and promoted GC migration and invasion in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, AK123072 could mediate the metastasis of hypoxia-induced GC cells. Next, we identified EGFR, which was a metastasis-related gene regulated by AK123072. In addition, we found that the expression of EGFR was positively correlated with that of AK123072 in the clinical GC samples used in our study. Furthermore, we found that the EGFR gene CpG island methylation was significantly increased in GC cells depleted of AK123072. Intriguingly, EGFR expression was also increased by hypoxia, and EGFR up-regulation by AK123072 mediated hypoxia-induced GC cell metastasis. Conclusion: Our results identified hypoxia/lncRNA-AK123072/EGFR pathway in gastric cancer pathogenesis and this might help in the development of new therapeutics in clinics.

Keywords: AK123702, cancer gene therapy, EGFR, gastric cancer (GC), hypoxia, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), metastasis, invasion

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in the world, and has a particularly high incidence in Asian countries including China [1]. The high mortality of GC is a consequence of late-stage of diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate for advanced stages is extremely poor and around 5% to 15% [2]. Although diagnosis and treatment of GC have improved, the survival rate has not increased substantially in couple of years. Therefore, an improved understanding of the molecular pathways involved in the progression of GC will be helpful in improving prevention, diagnosis and therapy of this disease [3]. Hypoxia is an important microenvironmental factor that induces such metastasis. In fact, hypoxic tumors are often aggressive and more likely to metastasize [4]. Therefore, investigating the underlying mechanisms of hypoxia-induced metastasis is critical.

LncRNAs have been identified as a new class of functional RNAs and have kindled our interest. LncRNAs are defined as transcripts of longer than 200 nucleotides without evident protein-coding function [5]. Few studies have implicated lncRNAs in various cancers [6,7], and several of the altered lncRNAs can result in the aberrant expression of nearby protein-coding genes, which may contribute to cancer development [8]. Studies have also demonstrated that lncRNAs play an important role in tumor development via various mechanisms, such as chromatin remodeling [9], DNA methylation [10], transcriptional regulation [11], and DNA damage repair [13]. All related processes play a pivotal role in malignant transformation and cancer treatment. However, the function of most lncRNAs in cancer remains a mystery, and lncRNA profiles in hypoxic GC and hypoxia-responsive gene networks remain unknown.

To explore the role of lncRNAs in hypoxic GC, we identified a small number of lncRNAs and messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that were aberrantly expressed in GC under hypoxia compared with normoxia using microarrays. We also investigated the biological function of the hypoxia-up-regulated AK123072 both in vivo and in vitro. Further analysis demonstrated that EGFR was over-expressed in several types of cancer [14,15]. In our study, the inhibition of lncRNA-AK123072 and EGFR were found to play an important role in hypoxia-induced metastasis and invasion, suggesting that manipulating new RNA functions can provide a therapeutic opportunity that is worth exploring.

Material and methods

Ethics statement

Investigation has been conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and according to the Declaration of Helsinki and according to national and international guidelines and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board.

Lentivirus infection and construction of stable cell lines with down-regulated lncRNA-AK123072

To observe the effects of AK123072 knockdown on invasion and metastasis in vivo and in vitro, four different small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that targeted AK123072 RNA and a scrambled siRNA control were generously provided by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The four siRNAs were transfected into SGC-7901 and AGS cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty-four hours after transfection, AK123072 expression levels were measured through reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and we found that siRNA-AK1 with the sequence 5’-CCACCAGUUACCUGCAAUATT-3’ (sense) and 5’-UAUUGCAGGUAACUGGUGGTT-3’ (antisense) and siRNAAK2 with the sequence 5’-GGAACAAAGAUGGUUUCUATT-3’ (sense) and 5’-UAGAAACCAUCUUUGUUCCTT-3’ (antisense) yielded the highest degree of AK123072 knockdown. Then, we designed and synthesized AK123072-targeting sequence and inserted this sequence into a Super-silencing Vector (GenePharma, Shanghai, China). An unrelated sequence lentiviral vector was used as a negative control. SGC-7901 and AGS cells were then plated into six-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 hours. Next, the lentivirus was transfected according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stably transfected cells were selected with puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and confirmed through fluorescence microscopy and RT-PCR.

Cell culture and transfection

Human gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901, AGS and BGC-823 were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were transiently transfected by electroporation or LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen) transfection reagent. For luciferase reporter gene assay, SGC-7901 cells (5×105) were seeded onto 6-well plates and then transiently transfected. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the transfected cells were infected with adenoviruses expressing miRNAs or GFP. Twenty-four hours after infection, luciferase activity was measured and then normalized.

MicroRNA real-time PCR

1×102-1×107 cells were harvested, washed in PBS once, and stored on ice; complete cell lysate was prepared by addition of 600 µl lysis binding buffer and vertex; 60 µl microRNA aomogenete addictive was added to the cell lysate and mixed thoroughly by inverting several times; sample was stored on ice for 10 min, followed by addition of equal volume (600 µl) of phenol: chloroform (1:1) solution; sample was mixed by inverting for 30-60 sec, and then centrifuged at 12000 g for 5 min; the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and the volume was estimated; 1/3 volume of 100% ethanol was added and mixed; the mixture was loaded to the column at room temperature and centrifuged at 10000 g for 15 sec; the flow-though was collected and the volume was then estimated; 2/3 volume of 00% ethanol was added and mixed; the mixture was loaded to column at room temperature and centrifuged at 10000 g for 15 sec; the flow-through was discarded; 700 µl microRNA wash solution was added to the column, followed by centrifugation at 10000 for 10 sec; the flow-through was discarded; 500 µl microRNA wash solution was added to the column, followed by centrifugation at 10000 for 10 sec; the flow-through was discarded; the column was transferred to a new tube and 100 µl preheated elution solution (95 degree) was added at room temperature; RNA was collected by centrifugation at 12000 g for 30 sec. The experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Western blot

Cells were harvested, washed twice in PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer (protease inhibitors were added immediately before use) for 30 min on ice. Lysate was centrifuged at 10000 rmp and the supernatants were collected and stored at -70 in aliquots. All procedures were carried out on ice. Protein concentration was determined using BCA assay kit (Tianlai Biotech). The experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2×103 cells/well) directly or 24 hours after transfection and allowed to attach overnight. Forty-eight hours later, cell viability was assessed via 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as described previously [14].

Transwell invasion assay

Transwell filters were coated with matrigel (3.9 mg/μL, 60-80 μL) on the upper surface of a polycarbonic membrane (diameter 6.5 mm, pore size 8 mm). After incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes, the matrigel solidified and served as the extracellular matrix for analysis of tumor cell invasion. Harvested cells (1×105) in 100 μL of serum free DMEM were added into the upper compartment of the chamber. A total of 200 μL conditioned medium derived from NIH3T3 cells was used as a source of chemo-attractant, and was placed in the bottom compartment of the chamber. After 24 h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the medium was removed from the upper chamber. The non-invaded cells on the upper side of the chamber were scraped off with a cotton swab. The cells that had migrated from the matrigel into the pores of the inserted filter were fixed with 100% methanol, stained with Hematoxylin, and mounted and dried at 80°C for 30 minutes. The number of cells invading through the matrigel was counted in three randomly selected visual fields from the central and peripheral portion of the filter using an inverted microscope (200× magnification). Each assay was repeated three times.

Plasmid construction and luciferase reporter assay

Wild-type 3’untranslated region (3’UTR) of EGFR containing predicted lncRNA-AK123072 target sites were amplified by PCR from SGC-7901 cell genomic DNA. Primers used: Forward: GAT CTG CAG GGG TTA GCT TGG GGA CCT GAA C; Reverse: GAT CAT ATG AGA GTG ACA TAC TGA TGC CTA C. Mutant 3’UTRs were generated by overlap-extension PCR method. Both wild-type and mutant 3’UTR fragments were subcloned into the pGL3-control vector (Promega, Madison, WI) immediately downstream of the stop codon of the luciferase gene. DNA fragment coding EGFR protein was amplified by PCR from SGC-7901 cell cDNA, and cloned into pCMV-Myc expression vector (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA). Primers used: Forward: GCT GAA TTC ATG CCG GTG GAC CTC AGC AAG T; Reverse: CTG CTC GAG CTA CTT CCC AGA CAG CTG CTC G. For luciferase assay, the reporter plasmid was co-transfected with a control Renilla luciferase vector into SGC-7901 cells in the presence of either miR-15b or NC. After 48 h, cells were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Animal studies

60 five-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Animal Center of Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China) and they were divided into 2 groups evenly. For in vivo metastasis assays, SGC-7901 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into nude mice (six per group, 1×106 cells for each mouse). Tumor growth was examined every other day, and tumor volumes were calculated using the equation V=A×B2/2 (mm3), where A is the largest diameter and B is the perpendicular diameter. After 2 weeks, all mice were sacrificed. Transplanted tumors were excised, and tumor tissues were used to perform hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining. All research involving animal complied with protocols approved by the Zhejiang medical experimental animal care commission.

Data analysis

Image data were processed using SpotData Pro software (Capitalbio). Differentially expressed genes were identified using SAM package (Significance Analysis of Microarrays, version 2.1).

Results

lncRNA expression profile in hypoxia-induced gastric cancer cells

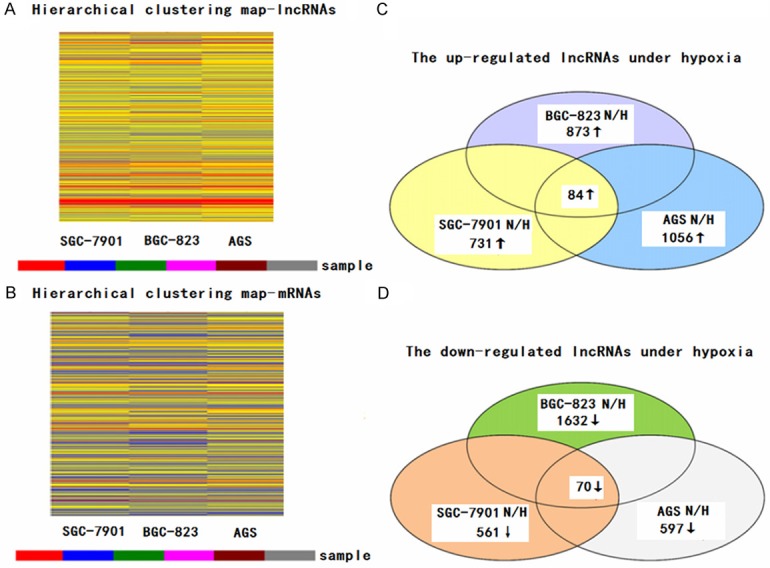

To examine the overall impact of lncRNAs on hypoxic GC, we analyzed the expression profiles of lncRNAs and protein-coding RNAs in normoxia-induced and hypoxia-induced GC cells using microarray analysis. Hierarchical clustering showed the differential lncRNA and protein coding RNA expression profiles between normoxia-induced and hypoxia-induced GC cells (Figure 1A and 1B). We set a threshold of a fold change >1.5, P<0.05, and found that 84 lncRNAs were up-regulated and 70 were down-regulated in all hypoxia-induced GC cells compared with normoxia-induced GC cells (Figure 1C and 1D). This finding indicated that the lncRNA expression profiles differed between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs were analyzed using hierarchical clustering. Hierarchical clustering analysis arranges samples into groups based on expression levels, which allows us to hypothesize the relationships between samples. The dendrogram shows the relationships between the lncRNA (A) and mRNA (B) expression patterns in the samples, that is, which samples are more similar in the expressing relationships. For every gene in each sample, the “Red” indicates high relative expression, and “Blue” indicates low relative expression. Actually, there is no inevitable relation between the lncRNA shown in (A) and mRNA presented in (B) expression patterns in the samples because they were analyzed independently. Schemas of the up-regulated (C) and down-regulated (D) lncRNAs, identified by microarray in the gastric cancer (GC) cells SGC-7901, AGS and BGC-823 under hypoxia. The overlapping areas represent the common lncRNAs in all three GC cell lines under hypoxia.

To validate the microarray findings, we randomly selected six lncRNAs from the differentially expressed lncRNAs with a fold change >3 and analyzed their expression through real-time PCR with hypoxia-induced GC cells (after 24 hours in 1% O2 for the SGC-7901, AGS, and BGC-823 gastric cancer cells) relative to normoxia induced GC cells.

Newly identified AK123072 frequently up-regulated in gc and induced by hypoxia in gc cells

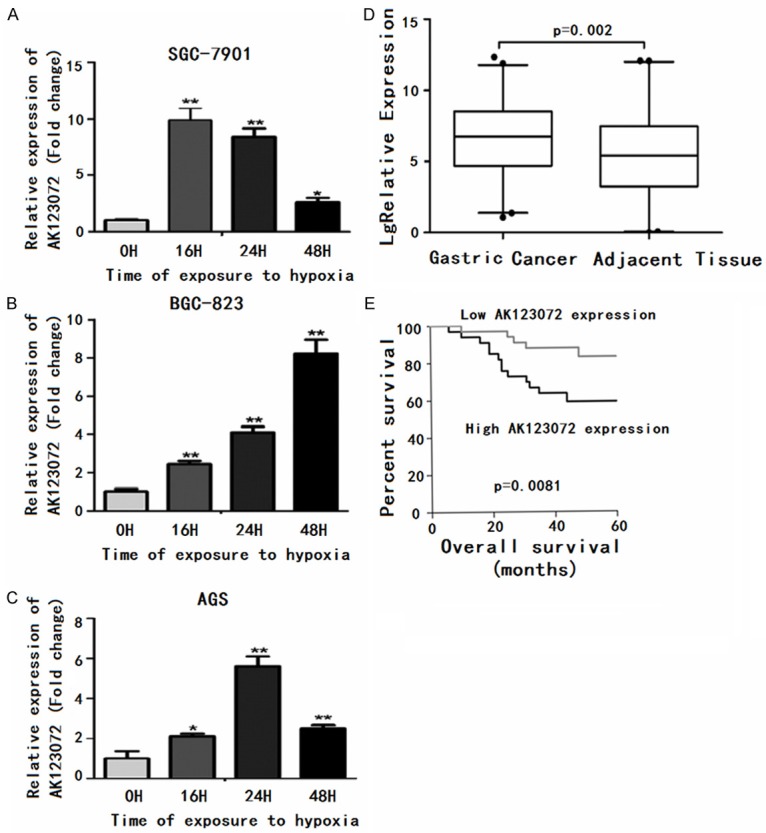

Among the differentially expressed lncRNAs among hypoxia induced GC cells and normoxia-induced GC cells, we were particularly interested in lncRNA-AK123072 because its expression increased approximately 6.20±1.65-fold upon hypoxia treatment in all three cell lines. Thus, we studied the role of AK123072, which is an intronic antisense lncRNA. Given that AK123072 is induced by hypoxia in GC cells, we next sought to determine whether AK123072 could be induced by hypoxia at different exposure times (after 4, 8, 16, 24, and 48 hours in 1% O2) in GC cells. We found that AK123072 was induced under hypoxia, with the most robust induction observed after 16 hours in 1% O2 for SGC-7901 cells, 24 hours in 1% O2 for AGS cells, and 48 hours in 1% O2 for BGC-823 cells (Figure 2A-C). The results suggested that AK123072 could indeed be regulated by hypoxia in GC cells; however, no significant difference was observed in expression after 4 or 8 hours in 1% O2.

Figure 2.

AK123072 is often up-regulated in gastric cancer and is induced by hypoxia in gastric cancer cells. (A-C) AK123072 was induced under hypoxia, with the most robust induction observed after 16 hours in 1% O2 in (A) SGC-7901 cells, 24 hours in 1% O2 in (B) AGS cells, and 48 hours in 1% O2 in (C) BGC-823 cells. (D) RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent from 95 pairs of human gastric cancer and adjacent tissues. AK123072 expression was assessed by real-time PCR. Actin was used as an internal control. The significant differences between samples were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P=0.002, n=95). (E) Patients with high levels of EGFR expression showed reduced overall survival times compared with patients with low levels of EGFR expression (P=0.0083, log-rank test). *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Next, we assessed AK123072 expression in 95 pairs of human primary GC tissues and adjacent gastric tissues using quantitative RT-PCR to determine AK123072 expression in GC tissues. AK123072 expression was remarkably up-regulated in GC tissues compared with non-cancerous gastric tissues (Figure 2D), indicating that AK123072 up-regulation is common in GC.

We further determined whether the expression level of EGFR correlated with the clinical outcome of gastric cancer patients. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests using patient postoperative survival were conducted to further evaluate the correlation between EGFR and prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. According to the median ratio of relative EGFR expression (5.44) in tumor tissues, the gastric cancer patients were classified into two groups: High-EGFR group: EGFR expression ratio ≥ median ratio; and Low-EGFR group: EGFR expression ratio ≤ median ratio. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that high EGFR expression in gastric carcinoma tissues is significantly associated with worse overall survival (P=0.0083, log-rank test) (Figure 2E). These results suggest that EGFR may play an important role in the progression of gastric cancer.

Effect of AK123072 on GC cell migration and invasion and hypoxia-induced migration and invasion

The frequent AK123072 up-regulation in hypoxic GC cells implies that AK123072 may play a role in hypoxia-induced GC. To test this hypothesis, the effects of reduced AK123072 expression on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion were investigated in two GC cell lines. Four different siRNA molecules were tested for their knockdown efficiencies, and the two most efficient of these molecules (siRNA-AK1 and siRNA-AK2) were selected for subsequent studies (Figure 3A). We first established SGC-7901 cell lines that stably repressed AK123072 expression by using anAK123072 siRNA-lentivirus (si-AK) vector, as verified by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3B) and RT-PCR (Figure 3D). To investigate whether AK123072 might have a role in hypoxia induced metastasis, we first determined whether AK123072 affected normoxic GC cell migration and invasion. In transwell assays with or without Matrigel, SGC-7901 cells with stable AK123072 knockdown showed significantly decreased migration and invasion compared with control cells (Figure 3E). Moreover, we examined cell motility in different groups under normoxia using high-content screening, which indicated that cell motility was reduced in AK123072 siRNA-lentivirus-treated cells compared with scrambled siRNA-treated cells (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results indicate that although AK123072 did not affect GC cell growth, the lncRNA promoted migration and invasion.

Figure 3.

AK123072 promotes gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. A. AK123072 expression following knockdown by four different siRNA (si-AK1, si-AK2, si-AK3, and si-AK4) in the GC cell lines SGC-7901. B. Observation of the infection efficiency of AK123072 (si-AK1 and si-AK2) and scrambled siRNA lentivirus (si-Scr) by fluorescence microscopy. C. After transfection, the cells were collected, and cell mobility assay was done to test the cell invasion ability. D. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901 cells were performed after transfection with AK123072 si-AK1 and si-AK2 or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr). E. Cell mobility was examined with a Cellomics ArrayScan VTI 1700 Plus. The relative distance traveled because of SGC-7901 cell mobility was calculated with this instrument. In all panels, the results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

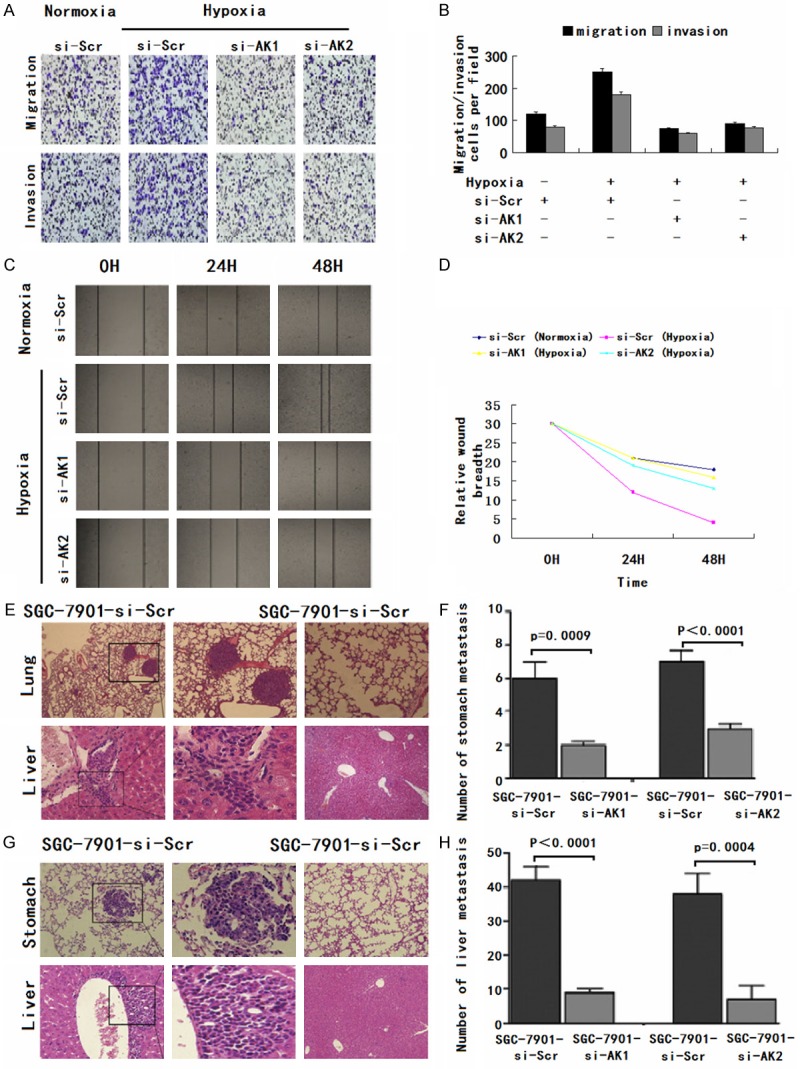

Given that AK123072 can promote normoxic GC cell migration and invasion, we hypothesized that AK123072 might play a role in hypoxia-induced migration and invasion. To test this hypothesis, we first measured hypoxic GC cell migration and invasion. Hypoxia significantly increased the migration and invasion potential of SGC-7901 cells (Figure 4A, 4B), which is consistent with previous reports [4,5]. After transfection with a siRNA-lentivirus to decrease endogenous AK123072 expression, the hypoxia-induced migration and invasion of SGC-7901 cells were dramatically diminished (Figure 4A, 4B). In addition, wound-healing assays showed that, under hypoxia, the cells more rapidly closed wounds (Figure 4C, 4D). However, after AK123072 knockdown in GC cells, wound healing was not significantly promoted under hypoxia compared with the control cells (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

AK123072 mediates hypoxia-induced gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. A, B. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901 cells were performed after transfection with AK123072 siRNA-lentivirus (si-AK1 and si-AK2) or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr) under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. C, D. Wound-healing assays were performed to evaluate the effect of AK123072 expression on cell migration. Cell culture plates with SGC-7901 cells that were transfected with AK123072 (si-AK1 and si-AK2) or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr). Cells were wounded and incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Healing was determined at the indicated times. E, F. The incidence of metastasis in mice and the mean number of visible tumor nodules in the liver and lung due to SGC-7901-transfected cells. SGC-7901 cells were transfected with the AK123072 siRNA-lentivirus (si-AK1 and si-AK2) or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr). The cells were then injected into nude mice via the tail vein for an in vivo metastasis assay, and the animals were sacrificed 6 weeks after injection. G, H. Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of stomach and liver isolated from mice injected with SGC-7901-si-Scr or SGC-7901-si-AK cells. The arrows indicate tumor foci in the lungs and livers. Magnification, ×100 (left) and ×200 (right).

To further explore the role of AK123072 in tumor invasion and metastasis in vivo, SGC-7901 cells with stable AK123072 repression by an AK123072 siRNA-lentivirus or a scrambled siRNA vector-transfected control cells were delivered into nude mice via tail vein injection. We found that the number and size of lung and liver metastatic nodules dramatically decreased in mice administered cells with low AK123072 expression compared with the scrambled siRNA controls (Figure 4G, 4H). Taken together, these observations suggest that AK123072 is a positive metastatic regulator of GC.

EGFR an AK123072-regulated gene in GC

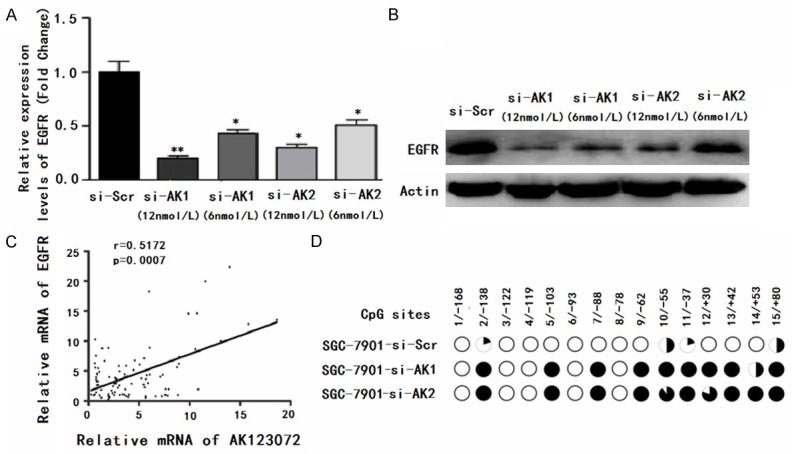

To explore the mechanism by which AK123072 promotes GC cell migration and invasion, we attempted to identify the lncRNA’s potential target genes. Recent studies have reported that lncRNAs may function by positively or negatively regulating the expression of their neighboring protein-coding genes [14,16,26-28]. Thus, we retrieved the genomic locus information from the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and found that the tumor oncogene EGFR is located 8.6 kb downstream of AK123072, whereas another tumor suppressor gene, BMPR1A, is found 33.3 kb upstream of AK123072. To validate the association between the lncRNA AK123072 and EGFR, we performed RT-PCR and western blotting using SGC-7901 and AGS cells with AK123072 knockdown. We observed significantly decreased EGFR levels in cells with low AK123072 expression compared with scrambled siRNA control cells (Figure 5A, 5B). Moreover, we showed that AK123072 suppressed EGFR mRNA and protein levels in GC cells and that there was a dose-dependent relationship between the expression of EGFR and AK123072 (Figure 5A, 5B). These results suggest that EGFR is an AK123072-regulated gene in GC. We also found that EGFR was predominantly located in the cytoplasm of GC cells. Moreover, we found that EGFR expression was heterogeneous in tumor tissue; it was predominantly located in the center of the tumor but had almost negative expression in the stroma of GC tissues.

Figure 5.

AK123072 up-regulates EGFR in gastric cancer cells. (A, B) The mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels of EGFR were assessed through RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively, SGC-7901 cells were transfected with an AK123072 siRNA-lentivirus (si-AK1 and si-AK2) or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr) in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Correlation between the relative mRNA levels of AK123072 and EGFR in 95 gastric cancer tissue specimens (r=0.5262, P<0.001, Pearson’s correlation). (D) Methylation mapping of 15 CpG island in EGFR exon 1 region obtained from bisulfite sequencing in scrambled siRNA control or SGC-7901 cells, or SGC-7901 cells infected with AK123072 siRNA. CpG positions are indicated relative to the translation start codon, and each circle in the figure represents a single CpG site. For each cell line, the percentage methylation at a single CpG site is calculated from the sequencing results of 10 independent clones. Black circles, 100% methylated; white circles, 0% methylation.

Next, we analyzed the correlation between EGFR expression and the clinicopathologic parameters of GC patients. EGFR expression in GC patients did not correlate with age, sex, or cell differentiation. We further investigated the correlation between AK123072 and EGFR expression in 95 clinical GC tissues and found that AK123072 and EGFR expression levels were positively correlated (Figure 5C). These observations indicate that EGFR is frequently up-regulated in GC samples, possibly because of AK123072 over-expression. Next, to investigate the potential mechanism by which AK123072 contributes to malignant behaviors of GC cells, we focused on DNA methylation of EGFR because lncRNAs are known to be involved in epigenetic regulation and DNA hypomethylation of EGFR has been confirmed in laryngeal cancer, including GC. Then, we performed bisulfite sequencing of cloned alleles over the region of -169 to 81 of the EGFR exon1 CpG islands, which has been demonstrated to be involved in GC. The results showed that EGFR CpG islands were densely hypomethylated in control SGC-7901-si-Scr and AGS-si-Scr cells, but GC cells transduced with AK123072 siRNA showed more methylated CpG dinucleotides (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results indicate that knockdown of AK123072 can down-regulate the expression of EGFR in GC cells by regulating EGFR DNA methylation, which illustrates that EGFR may act as a downstream target of AK123072 in GC cells.

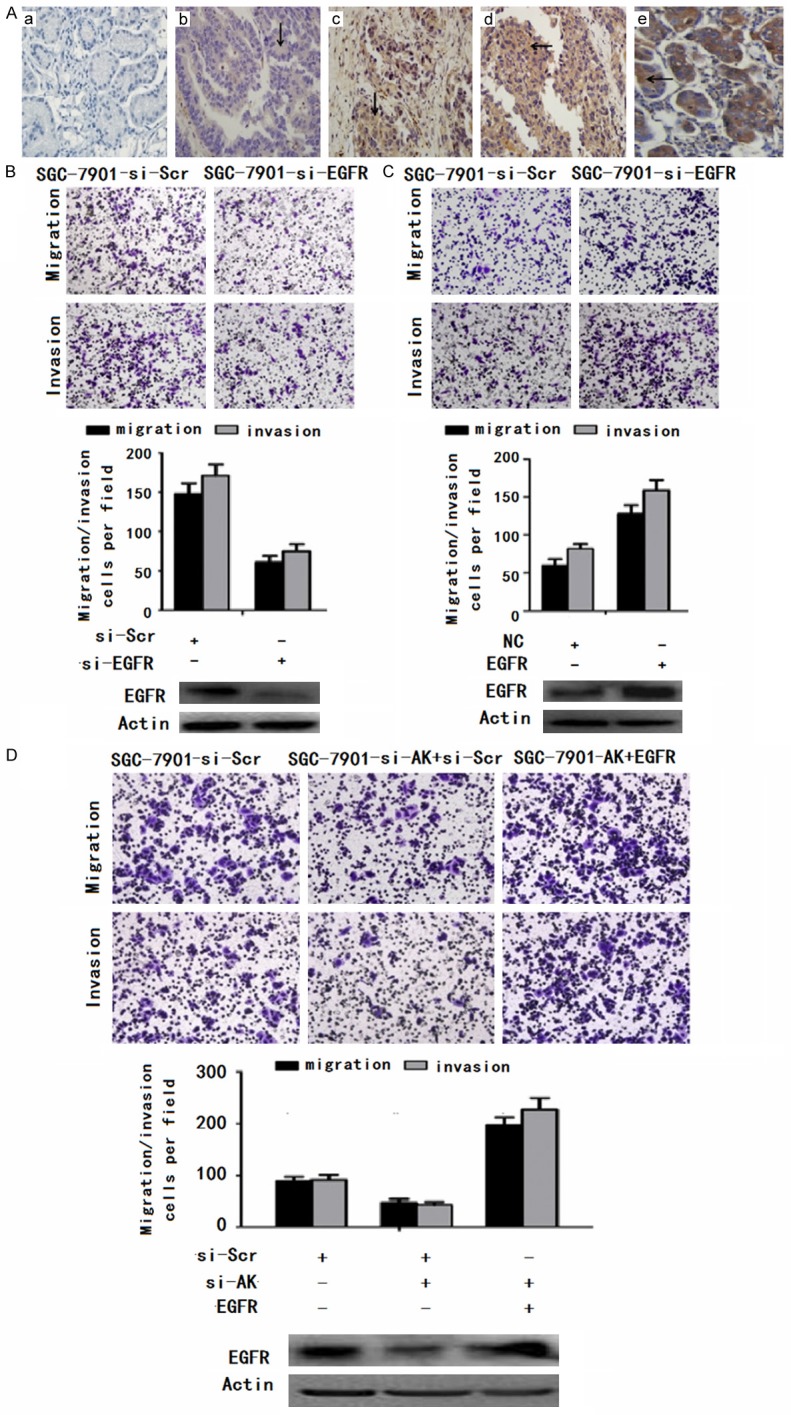

EGFR mediates AK123072-induced migration and invasion of GC cells

Additional analysis revealed that EGFR showed strong staining at primary sites from patients with metastatic GC compared with samples from patients with non-metastatic GC (Figure 6A). To further explore the biological function of EGFR in GC, siRNAs targeting EGFR were designed and transfected into SGC-7901 cells. These siRNAs significantly decreased EGFR expression (Figure 6C). The migration and invasion of the two cell lines were significantly decreased by EGFR siRNA but not by the scrambled siRNA control (Figure 6B and 6C). To support these findings, we over-expressed EGFR in SGC-7901 cells, which significantly increased cell migration and invasion (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

EGFR functions as a metastasis-related gene in gastric cancer and can promote AK123072-induced gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. A. Immunohistochemical analysis of EGFR in metastatic and nonmetastatic GC: (a) noncancerous region of GC, (b) primary site of nonmetastatic GC, (c, d) primary site of metastatic GC, and (e) breast cancer as positive control. B. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901 cells were performed after transfection with siRNA directed against EGFR or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr). EGFR protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis as well. C. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901 cells were performed after transduction with EGFR or a negative control. EGFR protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis as well. D. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901-si-Scr or SGC-7901-si-AK cells were performed after transduction with a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr) or EGFR. EGFR protein was detected by Western blot analysis as well. In all panels, the results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

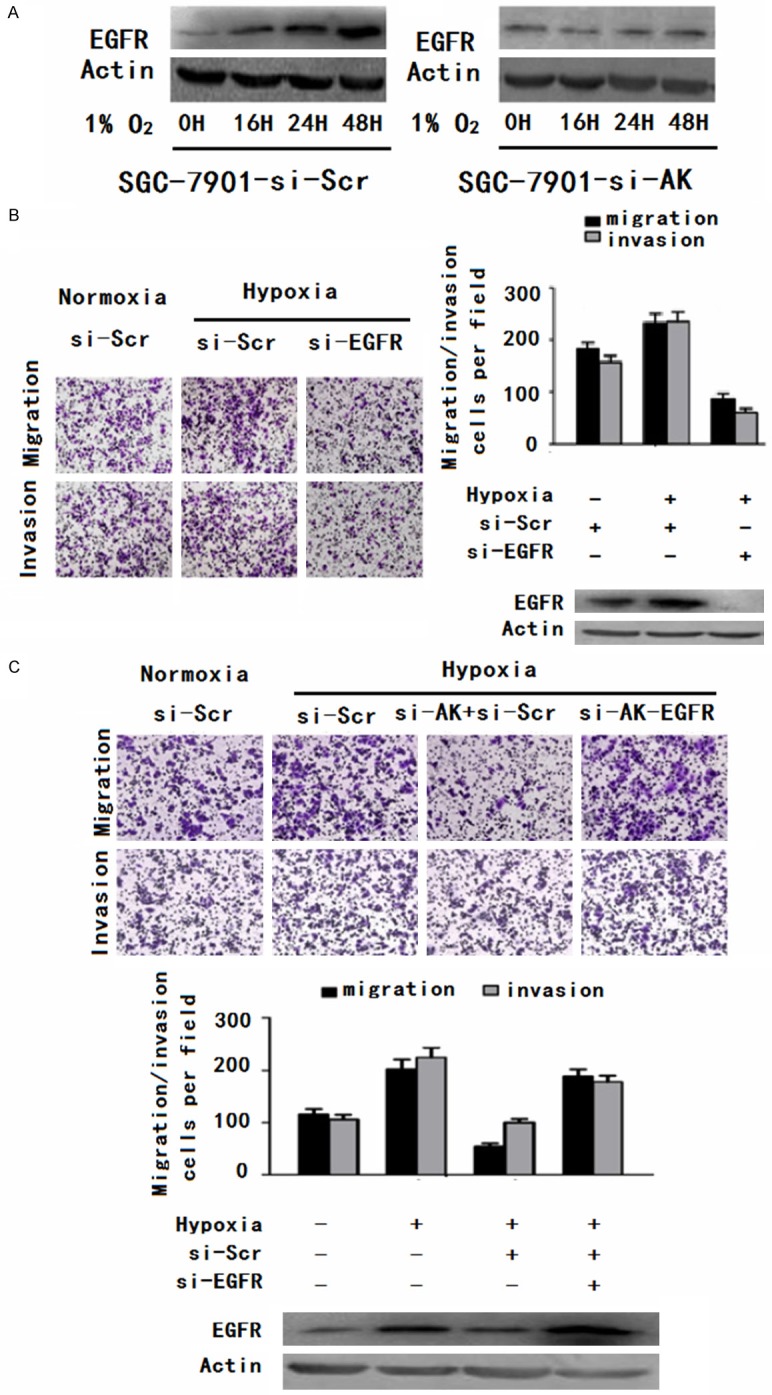

EGFR regulation by AK123072 mediates hypoxia-induced GC metastasis

To determine whether EGFR is involved in AK123072-induced hypoxic GC cell metastasis, we first detected EGFR expression under hypoxia. The results showed that EGFR expression in GC cells increased under hypoxia compared with normoxia (Figure 7A). When AK123072 expression was down-regulated in SGC-7901 cells, the hypoxia-induced EGFR increase was abrogated (Figure 7A), indicating that EGFR over-expression was mediated by AK123072 up-regulation under hypoxia. Moreover, transwell assays indicated that inhibiting EGFR expression promoted hypoxia-induced migration and invasion (Figure 7B). To determine the function of EGFR in AK123072-induced GC metastasis under hypoxia, an EGFR expression vector and a scramble control were co-transfected into SGC-7901 cells with stable AK123072 suppression. In transwell experiments, the impairment of the effects of siRNA-mediated AK123072 on hypoxia induced GC cell migration and invasion was partially relieved by EGFR but not by the negative control (Figure 7C). Taken together, these results indicate that EGFR expression is increased by hypoxia and that EGFR up-regulation by AK123072 mediates hypoxia-induced GC metastasis.

Figure 7.

Restoration of EGFR significantly increased the gastric cancer cell migration and invasiveness inhibited by AK123072 knockdown under hypoxia. A. EGFR protein levels in SGC-7901 cells. The cells were transfected with an AK123072 siRNA-lentivirus (si-AK) or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr) and then exposed to hypoxia after transfection. The cells were then collected and subjected to Western blot analysis at specific time points, as indicated. β-Actin served as an internal control. B. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901-si-Scr and SGC-7901-si-EGFR cells were performed under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. EGFR protein levels were determined by Western blot assays as well. C. Transwell migration and invasion assays of SGC-7901 cells were performed after transfection with an AK123072 siRNAlentivirus (si-AK), EGFR expression vector, or a scrambled siRNA control (si-Scr) under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. EGFR protein levels were determined through Western blot assays as well. In all panels, the results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Discussion

Gastric cancer is one of most common carcinomas worldwide. With the advances in the high-throughput gene sequencing analysis, our understanding of gastric cancer pathogenesis has improved through the identification of activating mutations in and amplifications of oncogenes [14], and inactivating mutations in tumor suppressive genes [15]. In the past decade, a growing volume of literature has identified a large number of miRNAs that contribute to the progression of gastric cancer [8-10]. However, the mechanism of gastric cancer progression, including the factors that promote cancer cell invasion, proliferation, apoptosis-resistance and chemo-therapy resistance remain largely unknown. Although accumulating evidence has indicated the role of lncRNAs in cancer, only a relatively small proportion of lncRNAs have been characterized. Our study demonstrates that, AK123072, an lncRNA, is clinically and functionally relevant to the development of gastric cancer. AK123072 was initially characterized in gastric cancer and found to promote gastric cancer cell proliferation via increasing c-Myc mRNA stability and expression [16]. Inspired by the observation that AK123072 is associated with the development of gastric cancer, we would like to explore its role in gastric cancer progression.

Hypoxia is an important micro-environmental factor in nearly every solid tumor, including GC, and it is related to an increased risk of metastasis and invasion [14,17]. The contribution of hypoxia-induced signaling pathways to malignancy is of great interest [17-19]. Previous studies found that many protein-coding genes associated with hypoxia correlation with GC metastasis and invasion [20]. However, the exact mechanism in this process has not been thoroughly elucidated. Recently, mounting evidence suggests that the expression of many lncRNAs is altered in different types of human cancer [21]. However, whether lncRNA is also involved in the hypoxic GC remains uncharacterized. In this study, as a first attempt to investigate whether lncRNA expression is altered under hypoxic conditions, we first searched for potential hypoxia-responsive lncRNAs using microarrays between hypoxia-induced GC cells and normoxia-induced GC cells. The results showed that hypoxia alters lncRNA expression and indicate that hypoxic GC may have specific lncRNA profiles. We then selected six lncRNAs from the differentially expressed lncRNAs with a fold change >3 and performed a quantitative RT-PCR to examine these lncRNAs’ expression levels in GC cells under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Of these six lncRNAs, only AK123072, which is a 1197-bp transcript and is located in the chromosome 10q22 on the forward strand, was strongly induced by hypoxia in three GC cells and up-regulated in GC samples. In addition, lncRNA-AK123072 was induced by hypoxia at a time-dependent manner in different GC cells. These data indicate the specificity of lncRNA-AK123072 in hypoxic induction. Moreover, we found that AK123072 mediated hypoxia-induced GC migration and invasion in vitro and in vivo. To our knowledge, this study is the first report demonstrating that an lncRNA enhances GC cell migration and invasion under hypoxia. Thus, our results suggest that lncRNA-AK123072 may not only act as a tumor hypoxia marker or adjust cells to hypoxic stress in tumors but may also have a biological role in tumor malignancy and metastasis.

Certain studies have revealed a strong correlation between EGFR expression in primary tumors and distant metastasis in many cancer types, including liver, esophageal, colon, gastric, lung, prostate, and cervical cancers. Furthermore, EGFR expression may be related to the tumor microenvironment [22,23]. In our study, we found that EGFR expression is increased in GC samples, particularly in metastatic tissues, and promotes GC metastasis. After analyzing the relationship between EGFR expression and the clinicopathologic factors of GC patients, we found a significant association between EGFR expression and the depth of tumor invasion, clinical tumor node metastasis stage, lymph node metastasis, and vascular invasion. Moreover, we observed that EGFR was also involved in hypoxia-induced GC metastasis. Furthermore, we found that the EGFR mRNA levels were positively correlated with the expression of AK123072 in 95 pairs of clinical GC samples. Accordingly, we have found that AK123072 knockdown could down-regulate EGFR expression at the mRNA and protein levels in a dose-dependent manner. These data demonstrated that EGFR down-regulation is at least partly caused by AK123072 down-regulation in GC. However, the mechanism of AK123072 regulation of EGFR is still unknown. Recent reports demonstrated that mature microRNAs repress protein expression primarily through base pairing of a seed region with the 3’-UTR of EGFR [24]. Furthermore, several studies reported that EGFR expression is activated by demethylation of the EGFR CpG island in the development of cancer, including GC [25-27]. Recently, increasing evidence confirmed that lncRNA can regulate DNA methylation of protein-coding genes during the development of disease [28-30].

In conclusion, our results indicated that lncRNA-AK123072 expression is frequently increased in hypoxic GC and promotes hypoxia-induced GC metastasis and invasion. EGFR, a metastasis associated gene in cancer that is involved in hypoxia-induced GC metastasis, was identified as a functional gene that was regulated by AK123072 through DNA demethylation. EGFR up-regulation by AK123072 mediates hypoxia-induced GC cell migration and invasion. Further study will explore the exact mechanism of EGFR DNA demethylation that is induced by AK123072. In summary, this finding suggests that the hypoxia/AK123072/EGFR pathway may contribute to the development of new anticancer therapeutics directed against hypoxic tumor targets.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Xie X, Liu HT, Mei J, Ding FB, Xiao HB, Hu FQ, Hu R, Wang MS. LncRNA HMlincRNA717 is down-regulated in non-small cell lung cancer and associated with poor prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8881–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Ma M, Liu W, Ding W, Yu H. Enhanced expression of long noncoding RNA CARLo-5 is associated with the development of gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8471–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng X, Shi H, Wang J, Cui S, Tang H, Zhang X. Long noncoding RNA aberrant expression profiles after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy of AGC ascertained by microarray analysis. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:5021–94. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan W, Liu L, Wei J, Ge Y, Zhang J, Chen H, Zhou L, Yuan Q, Zhou C, Yang M. A functional lncRNA HOTAIR genetic variant contributes to gastric cancersusceptibility. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:90–6. doi: 10.1002/mc.22261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang ZZ, Shen ZY, Shen YY, Xu J, Zhao EH, Wang M, Wang CJ, Cao H. HOTAIR long noncoding RNA promotes gastric cancer metastasis through suppression of Poly r(C) Binding Protein (PCBP) 1. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1162–70. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li LJ, Zhu JL, Bao WS, Chen DK, Huang WW, Weng ZL. Long noncoding RNA GHET1 promotes the development of bladder cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7196–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Shao Y, Zhang X, Zheng T, Miao M, Qin L, Wang B, Ye G, Xiao B, Guo J. Plasma long noncoding RNA protected by exosomes as a potential stable biomarker for gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:2007–12. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2807-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma G, Gu D, Lv C, Chu H, Xu Z, Tong N, Wang M, Tang C, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Wang B, Chen J. Genetic variant in 8q24 is associated with prognosis for gastric cancer in a Chinese population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:689–95. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, Hur K, Toden S, Saigusa S, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M, Boland CR, Goel A. Metastasis-associated long non-coding RNA drives gastric cancer development and promotes peritoneal metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2731–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Wang J, Qian J, Kong X, Tang J, Wang Y, Chen H, Hong J, Zou W, Chen Y, Xu J, Fang JY. Long noncoding RNA GAPLINC regulates CD44-dependent cell invasiveness and associates with poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6890–902. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Sun J, Song Y, Gao P, Zhao J, Huang X, Liu B, Xu H, Wang Z. The novel long noncoding RNA AC138128.1 may be a predictive biomarker ingastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31:262. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding J, Li D, Gong M, Wang J, Huang X, Wu T, Wang C. Expression and clinical significance of the long non-coding RNA PVT1 in humangastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1625–30. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S68854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Tan X, Wang X, Jin H, Liu L, Ma L, Yu H, Fan Z. C-Myc-activated long noncoding RNA CCAT1 promotes colon cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:12181–8. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu TP, Huang MD, Xia R, Liu XX, Sun M, Yin L, Chen WM, Han L, Zhang EB, Kong R, De W, Shu YQ. Decreased expression of the long non-coding RNA FENDRR is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer and FENDRR regulates gastric cancer cell metastasis by affecting fibronectin1 expression. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:63. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0063-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Chen S, Yang G, Gu F, Li M, Zhong B, Hu J, Hoffman A, Chen M. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR as an independent prognostic marker in cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia T, Liao Q, Jiang X, Shao Y, Xiao B, Xi Y, Guo J. Long noncoding RNA associated-competing endogenous RNAs in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6088. doi: 10.1038/srep06088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S, Li P, Xiao B, Guo J. Long noncoding RNA HMlincRNA717 and AC130710 have been officially named as gastric cancer associated transcript 2 (GACAT2) and GACAT3, respectively. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8351–2. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2378-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma MZ, Chu BF, Zhang Y, Weng MZ, Qin YY, Gong W, Quan ZW. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1 promotes gallbladder cancer development via negative modulation of miRNA-218-5p. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1583. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizrahi I, Mazeh H, Grinbaum R, Beglaibter N, Wilschanski M, Pavlov V, Adileh M, Stojadinovic A, Avital I, Gure AO, Halle D, Nissan A. Colon Cancer Associated Transcript-1 (CCAT1) Expression in Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach. J Cancer. 2015;6:105–10. doi: 10.7150/jca.10568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu MD, Qi P, Weng WW, Shen XH, Ni SJ, Dong L, Huang D, Tan C, Sheng WQ, Zhou XY, Du X. Long non-coding RNA LSINCT5 predicts negative prognosis and exhibits oncogenic activity in gastric cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e303. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagatsuma AK, Aizawa M, Kuwata T, Doi T, Ohtsu A, Fujii H, Ochiai A. Expression profiles of HER2, EGFR, MET and FGFR2 in a large cohort of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:227–38. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Cao J, Li J, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Peng W, Sun S, Zhao N, Wang J, Zhong D, Zhang X, Zhang J. A phase I study of AST1306, a novel irreversible EGFR and HER2 kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye B, Jiang LL, Xu HT, Zhou DW, Li ZS. Expression of PI3K/AKT pathway in gastric cancer and its blockade suppresses tumor growth and metastasis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:627–36. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie J, Chen M, Zhou J, Mo MS, Zhu LH, Liu YP, Gui QJ, Zhang L, Li GQ. miR-7 inhibits the invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells by suppressing epidermal growth factor receptor expression. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:1715–22. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang L, Chen Y, Li Y, Lan T, Wu M, Wang Y, Qian H. Type II cGMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits ligand-induced activation of EGFR ingastric cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:1405–9. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Piazuelo MB, Yan F, Barry DP, Sierra JC, Delgado AG, Hill S, Casero RA Jr, Bravo LE, Dominguez RL, Correa P, Polk DB, Washington MK, Rose KL, Schey KL, Morgan DR, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT. Activation of EGFR and ERBB2 by Helicobacter pylori results in survival of gastricepithelial cells with DNA damage. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1739–51. e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gala K, Chandarlapaty S. Molecular pathways: HER3 targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1410–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agaimy A, Rau TT, Hartmann A, Stoehr R. SMARCB1 (INI1)-negative rhabdoid carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: clinicopathologic and molecular study of a highly aggressive variant with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:910–20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tajiri R, Ooi A, Fujimura T, Dobashi Y, Oyama T, Nakamura R, Ikeda H. Intratumoral heterogeneous amplification of ERBB2 and subclonal genetic diversity in gastric cancers revealed by multiple ligation-dependent probe amplification and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:725–34. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi M, Shi H, Ji J, Cai Q, Chen X, Yu Y, Liu B, Zhu Z, Zhang J. Cetuximab Inhibits Gastric Cancer Growth in vivo, Independent of KRAS Status. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2014;14:217–24. doi: 10.2174/1570163811666140127145031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]