Abstract

Background and aims Flower meristems differ from vegetative meristems in various aspects. One characteristic is the capacity for ongoing meristem expansion providing space for new structures. Here, corona formation in four species of Passiflora is investigated to understand the spatio-temporal conditions of its formation and to clarify homology of the corona elements.

Methods One bird-pollinated species with a single-rowed tubular corona (Passiflora tulae) and three insect-pollinated species with three (P. standleyi Killip), four (P. foetida L. ‘Sanctae Martae’) and six (P. foetida L. var. hispida) ray-shaped corona rows are chosen as representative examples for the study. Flower development is documented by scanning electron microscopy. Meristem expansion is reconstructed by morphometric data and correlated with the sequential corona element formation.

Key Results In all species, corona formation starts late in ontogeny after all floral organs have been initiated. It is closely correlated with meristem expansion. The rows appear with increasing space in centripetal or convergent sequence.

Conclusions Based on the concept of fractionation, space induces primordia formation which is a self-regulating process filling the space completely. Correspondingly, the corona is interpreted as a structure of its own, originating from the receptacle. Considering the principle capacity of flower meristems to generate novel structures widens the view and allows new interpretations in combination with molecular, phylogenetic and morphogenetic data.

Keywords: Corona, de novo structures, flower meristem, fractionation, meristem expansion, morphogenesis, Passiflora foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’, P. foetida var. hispida, P. standleyi, P. tulae, self-organization, space

INTRODUCTION

Flowers are usually defined as short shoots with reproductive organs. However, their meristems differ from vegetative shoot apical meristems in being determinate and highly plastic (Ronse de Craene, 2010; Claßen-Bockhoff, 2015). Differential meristem activity (Leins and Erbar, 2008) provides flowers with a broad developmental potential, reflected in the exciting diversity of flower shapes and functions.

One of the typical flower capacities is represented by the formation of a corona, i.e. an attractive structure located between the petals and stamens. The well-known examples from the Amaryllidaceae (Narcissus, Pancratium) have been controversially interpreted within the last 150 years as originating either from the perigon (Eichler, 1875; Arber, 1937; Chen, 1971; Singh, 1972) or from stamens (Čelakovský, 1898; Velenovský, 1910; Glück, 1919; Goebel, 1933; Schaeppi, 1939). Phylogenetic data indicate that the corona evolved several times in parallel in this lineage, allowing for different morphogenetic origins (Meerow et al., 1999; Waters et al., 2013).

Less well known yet equally conspicuous is the corona in the passionflower Passiflora (Passifloraceae). The attractive flowers belong to the most loved ornamental plants in the world. The first reports date back to the 16th century when the peculiar shape of the floral structures was interpreted as a symbol of the passion of Christ, from whence came the name of the flower (Kugler and King, 2004).

Passiflora is the largest genus in the Passifloraceae, with >500 species (Krosnick and Freudenstein, 2005). Flowers are actinomorphic and pentamerous, exposing an androgynophore with five anthers and three styles (Figs 1 and 2). As nectar is hidden at the base of the flower, the pollinator moves around the androgynophore. In young flowers, the anthers come into contact with the pollinators and load pollen on their head or back. In older flowers, the stylar arms bend backwards and pollen is transferred to the receptive tissue (Janzen, 1968).

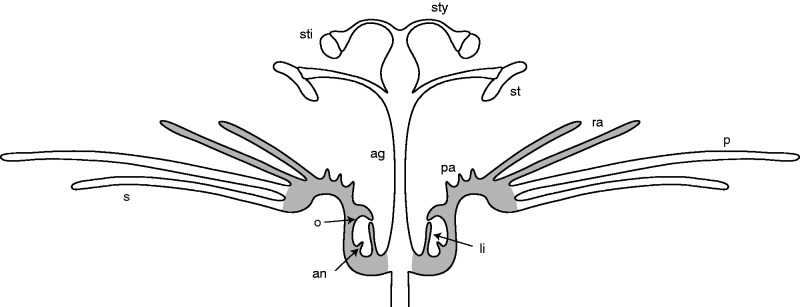

Fig. 1.

Passiflora. Schematic side view of a typical flower illustrating floral structures. Grey shading, flower cup after full expansion with corona elements and limen. ag, androgynophore, an, annulus, li, limen, o, operculum, p, petal, pa, pali, ra, radii, s, sepal, st, stamen, sti, stigma, sty, stylus.

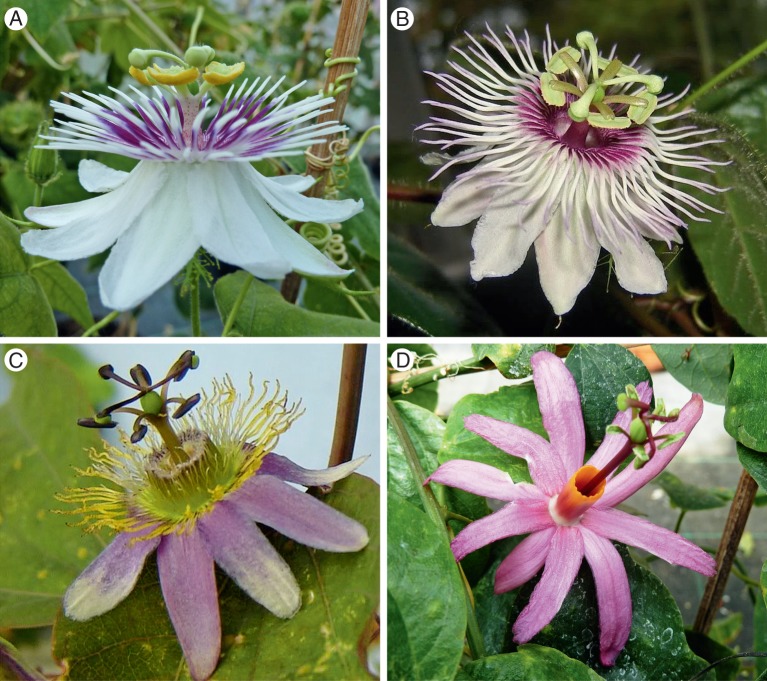

Fig. 2.

Passion flowers. (A) Passiflora foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’. (B) Passiflora foetida var. hispida. (C) Passiflora standleyi. (D) Passiflora tulae.

The most attractive element of the flower is the corona, which is highly diverse in the number, shape, size and colour of its elements. Following the terminoloy of Puri (1948), the complete set of structures includes (in centripetal order) long filamentous structures, called ‘radii’, short structures called ‘pali’, and the ‘operculum’ which is the bulge-shaped inner border of the corona (Fig. 1). Together with the ‘limen’, an effiguration close to the androgynophore, the operculum covers the nectar-producing tissue, called the annulus.

As in Narcissus, the corona in Passiflora has been controversially interpreted. Lindley (1830), Puri (1947, 1948) and de Wilde (1974) discussed a morphogenetic origin from the sepals and petals, while Masters (1871) interpreted the structures as ‘organs sui generis’. From a systematic point of view, Endress (1996) assumed that the corona elements may correspond to a group of modified staminodes. However, ontogenetic studies did not confirm this view (Bernhard, 1999).

In the present paper, the genesis of the corona in passionflowers is investigated to understand its formation with respect to space. Given that the flower meristem is determinate with no potential for apical growth, it has the capacity to expand on all sides (Claßen-Bockhoff, 2015). It is assumed that corona formation is coupled to meristem expansion, providing space for additional structures. To test this hypothesis, flower development is investigated in four Passiflora species differing in the number and shapes of their corona elements (Fig. 2). Passiflora foetida var. hispida and P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ (both subgenus Passiflora, sect. Dysosmia) have six and four series of corona elements, respectively. Passiflora standleyi has three rows and P. tulae has a single-row tube-like corona (both subgenus Decaloba, section Decaloba). The focus of the study is on meristem conditions, corona initiation and element formation during flower development. If the flower meristem expands during primordia production, space may play a significant role in generating diversity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Passiflora foetida var. hispida, P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’, P. standleyi and P. tulae are grown at the Botanical Garden at Mainz University, Germany. Cuttings originated from the nursery ‘Blumen & Passiflora’, Witten, Germany. Flowers are 4–6 cm in diameter and pollinated by bees, except P. tulae which is hummingbird-pollinated (Janzen, 1968).

Buds of different age were picked from the plants and fixed in 70 % ethanol. Longitudinal dissections were made with razor blades, which were regularly replaced with new ones. After removing the stamen and carpel primordia, the probes were incubated in 80, 90 and 96 % ethanol, each step for 30 min. After that, material was transferred to 1:1 ethanol–acetone and then to 100 % acetone. Critical-point drying was conducted using a BAL-TEC CPD030 instrument with CO2 as exchange agent. The probes were sputtered with gold (BAL-TEC SCD005) and analysed under an XL 30 ESEM scanning electron microscope (Philipps). Each step was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

In total, 178 buds and flowers were dissected and 145 probes analysed under the SEM. To correlate meristem expansion with corona element formation, developmental stages were defined for each species. The dimensions of at least eight probes per species and stage were measured in a standardized way using Imagic ims Client 12v. The results are documented by boxplots using QtiPlot 65v. As corona development is a continuous process, transitional forms appear as extreme values within the defined stages and are indicated by the standard deviation.

RESULTS

Flower formation

The four Passiflora species grow as lianas. The shoot apical meristem remains vegetative and produces leaf primordia in a spiral sequence (Fig. 3A: 1–10). Axillary meristems appear at a few nodes off the apex and start to expand laterally. In P. standleyi, each meristem develops three parts (Fig. 3B, C). The largest part gives rise to the tendril meristem (tm), while the two lateral parts originate lateral flowers (fm). Each flower is subtended by a bract (fsb) and has two prophylls (pp) (Fig. 3D, E). Due to intercalary activity, the three bracts are dislocated in a concaulescent way and finally form an outer calyx below the flower. At this time, an accessory meristem part appears in the adaxial–median position (Fig. 3E, F). It produces leaves with stipules, indicating that it is a vegetative meristem. Indeed, lateral branches originate from the accessory buds in a later ontogenetic stage.

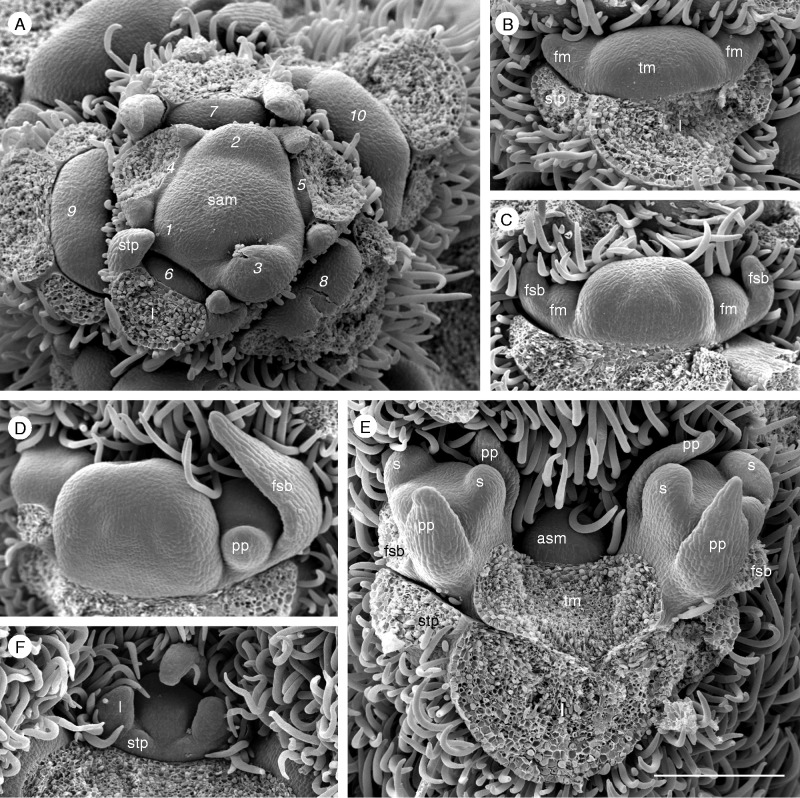

Fig. 3.

Shoot development in Passiflora standleyi. (A) The shoot apical meristem (sam) segregates leaves (l) with stipules (stp) in a spiral sequence. 1–10, downwards sequence of lateral primordia and axillary meristems. (B–D) The axillary meristem merges into the tendril meristem (tm) and forms two lateral meristems giving rise to subtending bracts (fsb), prophylls (pp) and flower meristems (fm). (E) When sepals (s) arise, an accessory meristem part (asm) appears in the adaxial median position. (F) This produces stipulated leaves, indicating its vegetative nature. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Flower development is highly similar among the four species. In P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ and P. foetida var. hispida, five sepal primordia appear in a spiral sequence (Fig. 4A). After meristem expansion, five petal primordia follow in alternate positions (Fig. 4B). Next, five anther primordia appear opposite the sepals. They are roundish and in part covered by the growing petals (Fig. 4C). When the three carpel tips arise, filaments separate from the anthers (Fig. 4D, E: fi). The carpels continue to grow while the tissue below the petals and sepals starts to extend and to form a receptacular cup (Fig. 4F, G: cu). This cup gradually expands with ongoing ovary and anther development, providing space between the petals and anthers (Fig. 4H: arrow). In this space, called the ‘corona insertion area’ (cia), the first corona elements appear when the pollen sacs are initiated, and the ovary continues elongating (Fig. 4I, H). With ongoing anther and style development, cup expansion continues, allowing more and more corona elements to be formed (Figs 5–10).

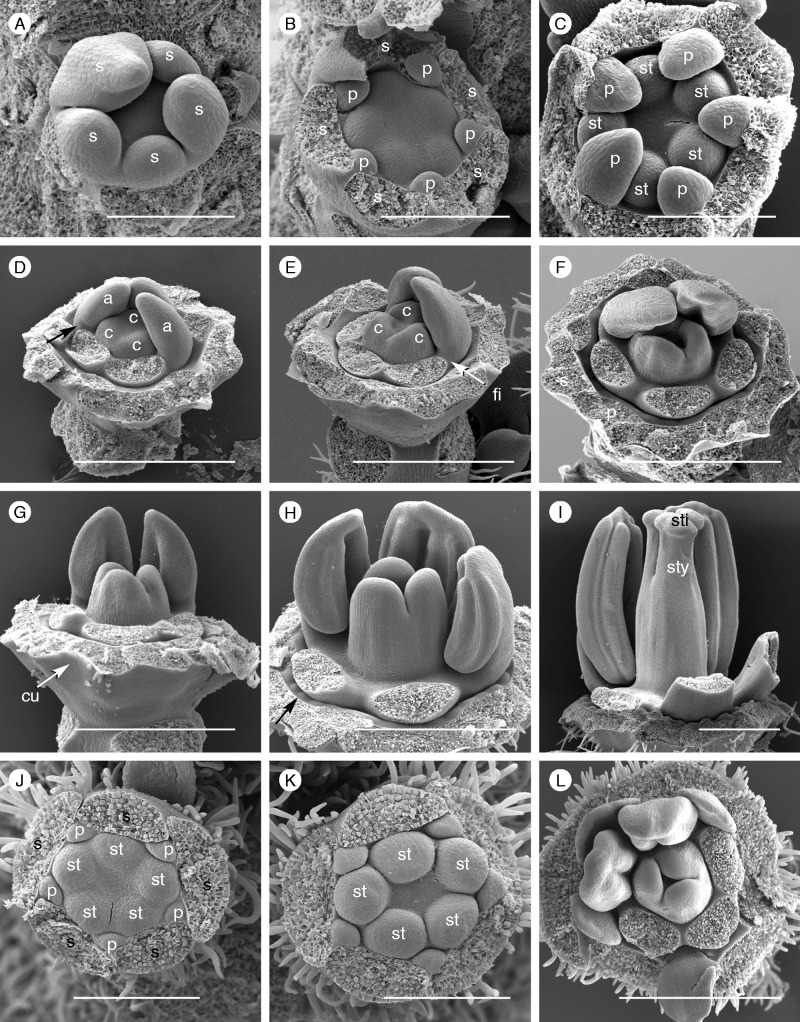

Fig. 4.

Flower development. (A–I) Passiflora foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ (also representing P. foetida var. hispida). (A) Sepals (s) develop in a spiral sequence. (B) Petal primordia (p) appear almost simultaneously followed by five stamen primordia. (C) Petals elongate and cover the stamen primordia (st); their slightly elevated insertion area indicates the beginning of flower cup formation. (D, E) When the filaments (fi) start to elongate (arrows), three carpel (c) tips appear in the centre of the flower. (F) The carpel tips elongate and the cup continues to grow, separating petals from stamens. (G, H) The first corona elements (black arrow) appear at the inner side of the cup (cu). (I) Styles (sty) and stigmas (sti) differentiate at the tip of the ovary; the androgynophore has not yet developed. (J–L) Passiflora standleyi (also representing P. tulae). The two species from Passiflora subgenus Decaloba differ in two aspects from flower development in P. foetida: petal growth is retarded compared with stamen development (J, K) and corona elements appear in a later stage; in stage L, which is comparable with stage H, no corona elements are visible. Scale bars = 200 µm (A–C, J, K), 500 µm (D–I).

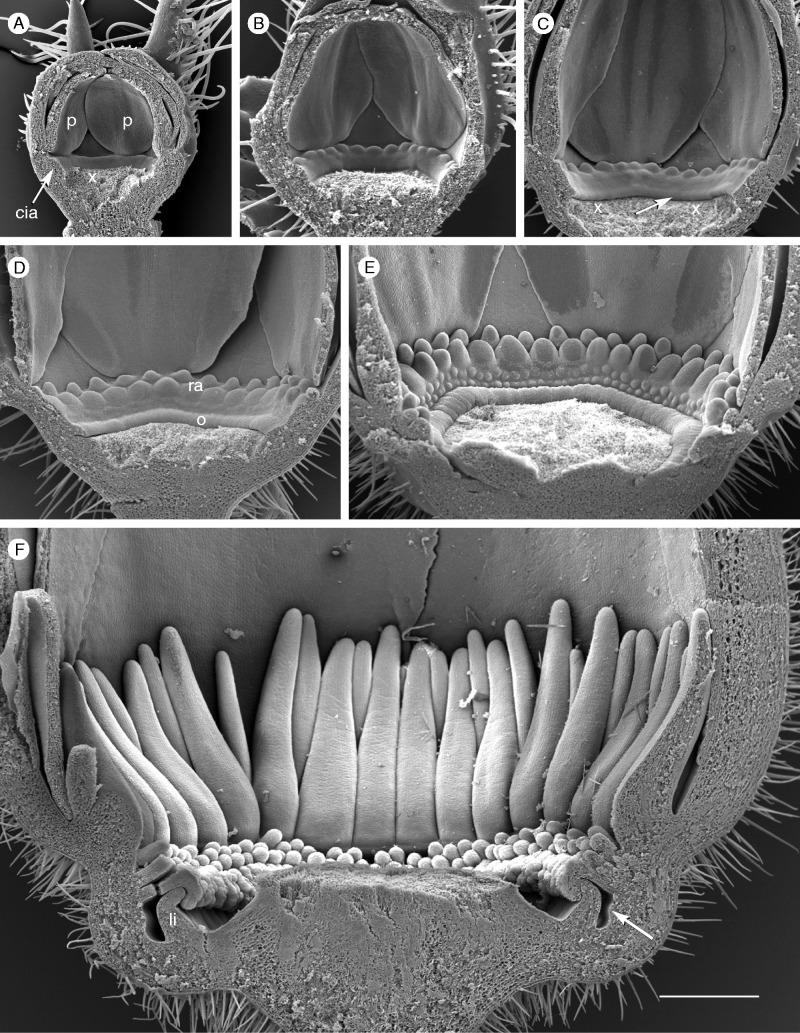

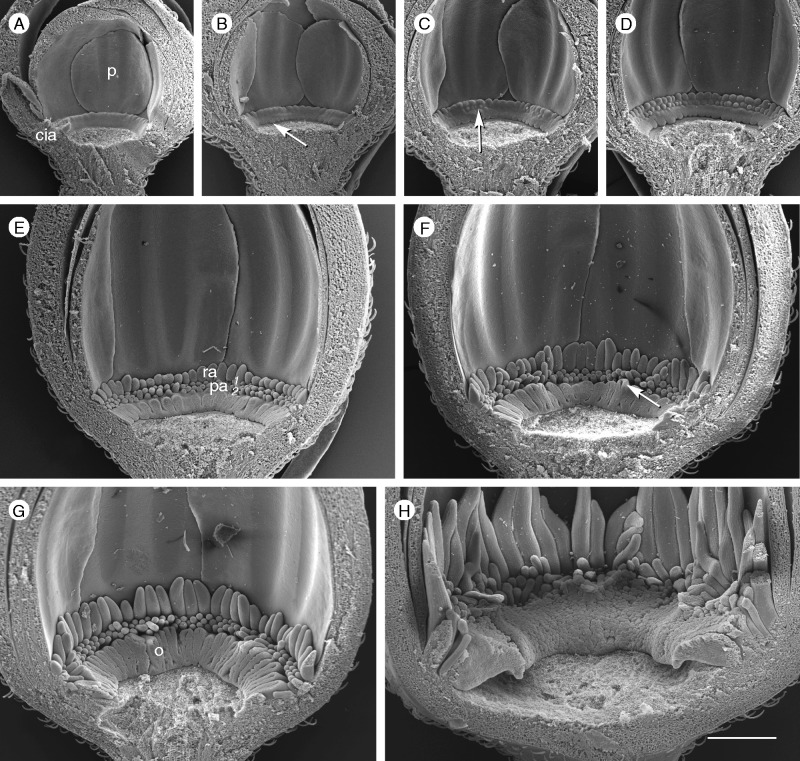

Fig. 5.

Corona development in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ (androecium and gynoecium removed). (A, B) Stage 1: the expanding receptacle forms a bulge (cia) at its inner side; first radii appear at its upper rim. (C) Stage 2: the operculum (arrow) forms the lower rim of the developing corona (st age 2). (D) Stage 3: the second row of radii (ra) is completed; the operculum (o) is distinct. (E) Stage 4: two rows of pali appear almost simultaneously. (F) All elements of the corona are formed; the operculum and limen cover the nectar-secreting annulus (arrow). All images are at the same scale. Scale bar = 500 µm.

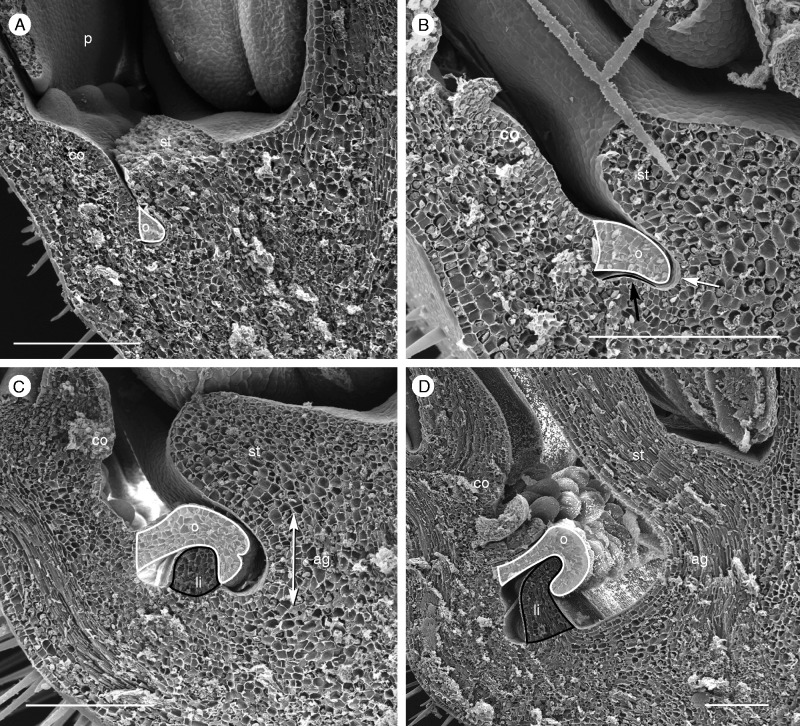

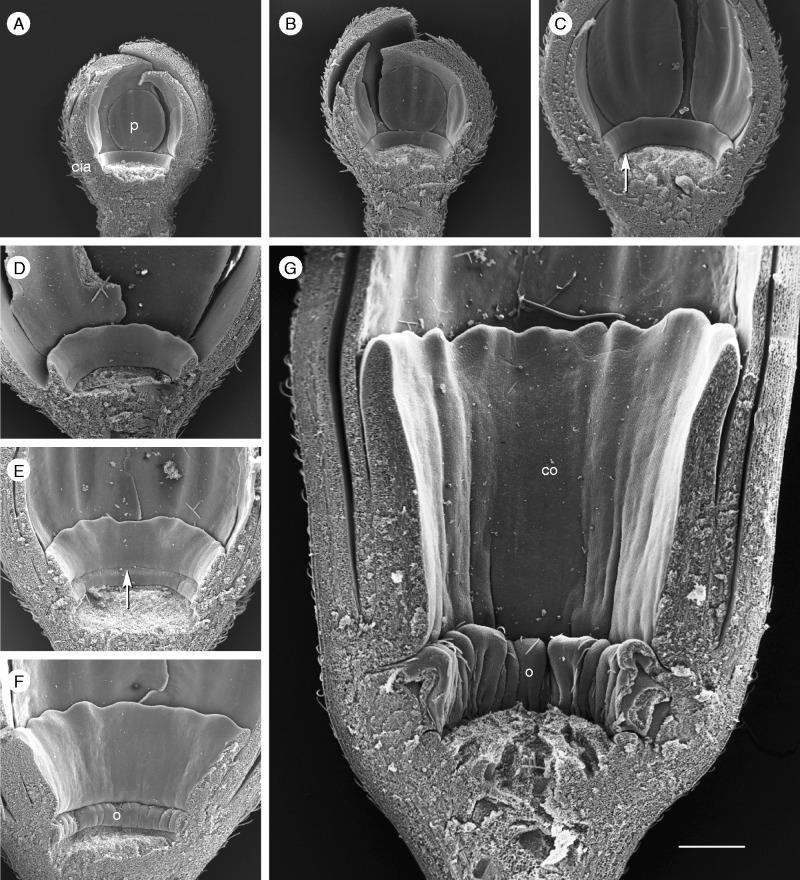

Fig. 6.

Limen formation in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’. (A, B) When the receptacle widens, space is provided between the developing operculum (o) and the stamen (st) base; below the operculum a ring-shaped hollow is formed (white arrow). The limen originates as an emergence of the receptacle (B: black arrow; co, corona). (C, D) When the androgynophor (ag) elevates the stamen base, further space is provided. Operculum and limen enlarge and form the nectar chamber. Scale bar = 200 µm.

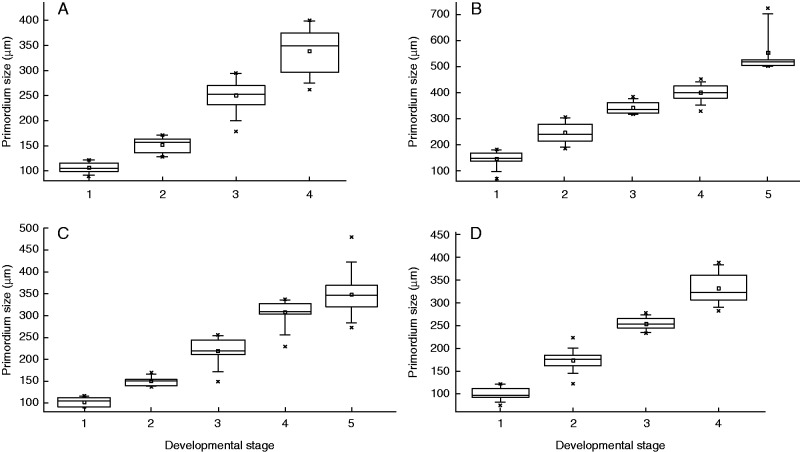

Fig. 7.

Temporal relationship between flower cup expansion (primordium size) and developmental stage of the corona. (A) P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’. (B) P. foetida var. hispida. (C) P. standleyi. (D) P. tulae. Stage 1: formation of first radii. Stage 2: formation of the operculum. Stage 3: formation of the second corona series (radii in A, pali in C), simultaneous formation of the second radii series and forth pali series (B), constriction between radii and operculum (D). Stage 4: simultaneous fractionation of two rows of pali (A), fractionation of third (B) and second series of pali (C) and massive folding of the operculum (D). Stage 5: simultaneous formation of the two last pali series (B) and massive folding of the operculum (C).

Fig. 8.

Corona development in P. foetida var. hispida (androecium and gynoecium removed). (A, B) Stage 1: formation of the bulge and first radii (p, petal). (C) Stage 2: development of the operculum (arrow). (D, E) Stage 3: the second row of radii (2) and the lowest row of pali (6) appear simultaneously. (F) Stage 4: the second series of pali is formed; the operculum and limen cover the nectar chamber (arrow). (G) Stage 5: the last two series of pali appear simultaneously. (H) The corona is completed and all elements start to elongate. All images are at the same scale. Scale bar = 500 µm.

Fig. 9.

Corona development in P. standleyi (androecium and gynoecium removed). (A) Stage 1: the corona insertion area (cia) is present and the first radii are formed (p, petal). (B) Stage 2: operculum appears (arrow). (C, D) Stage 3: the first row of pali is formed (arrow). (E) Stage 4: the second row of pali (pa) appears (ra, radii). (F–H) The operculum (o) forms a massive ring due to ongoing meristem expansion. All images are at the same scale. Scale bar = 500 µm.

Fig. 10.

Corona development in P. tulae (androecium and gynoecium removed). (A, B) Stage 1: the corona insertion area (cia) forms a bulge and separates from the petals (p) by an upper rim. (C) Stage 2: the operculum (arrow) appears. (D, E) Stage 3: the upper rim starts to elongate and to form the corona tube; the operculum separates from the tube by a clear constriction (arrow). (F, G) Stage 4: the operculum and tube continue to grow. All images are at the same scale. Scale bar = 500 µm.

Flower development in P. standleyi and P. tulae only differs from the described sequence in a different timing of organ development. Petal growth is retarded (compare Fig. 4C, K) and the first corona elements appear later, i.e. after ovary development (compare Fig. 4H, L).

Corona development

The four species clearly differ in number and shaping of the corona elements (Fig. 2). They have in common that the corona is always formed in a late stage of flower development when space is made available by meristem expansion.

Passiflora foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’

Corona development in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ passes through four stages which are each defined by the formation of a new structure. The starting point is the cia, which appears as a flat bulge on the inner side of the receptacular cup between petal and anther primordia (Fig. 5A).

Stage 1. The cia spans about 100 µm (Table 1). The first radii appear as small effigurations at its distal border (Fig. 5B).

Table 1.

Corona meristem expansion during development (median values and standard deviation)

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Stage 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. foetida‚ Sanctae Martae’ (n ≥ 12) | 105·5 ± 12·1 | 156·9 ± 16·0 | 253·0 ± 32,3 | 339·1 ± 46·5 | |

| P. foetida var. hispida (n ≥ 10) | 145·7 ± 30·6 | 240·5 ± 41·8 | 341·9 ± 23·1 | 399·6 ± 35·8 | 517·4 ± 82·8 |

| P. standleyi (n ≥ 8) | 104·4 ± 11·2 | 149·9 ± 11·1 | 219·5 ± 31·9 | 309·1 ± 28·5 | 348·1 ± 52·6 |

| P. tulae (n ≥ 9) | 97·0 ± 12·8 | 176·1 ± 22·2 | 252·7 ± 14·3 | 332·6 ± 33·1 |

The stages are species specifically defined and not directly comparable.

n, number of samples; bold, compare with Fig. 11.

Stage 2. The operculum appears (Fig. 5C: arrow). When the cup is >150 µm extended, the proximal border of the corona tissue arches upwards. Thereby, the cia becomes clearly separated from the remaining tissue. Below the protruding operculum, a narrow ring-shaped hollow is formed. At the same time, the first radii of the second row appear.

Stage 3. The second series of radii (ra) is completed. The cia measures about 250 µm (Fig. 5D; Table 1).

Stage 4. The two series of pali appear simultaneously; the cia and operculum continue growth (Fig. 5E). The meristem tissue between the operculum and the base of the stamens doubles its size (from approx. 20 µm to >200 µm; Fig. 6A, B: o, st). The limen (li) appears as an outgrowth (Fig. 6B, C). As soon as the androgynophor (ag) elongates and provides further space at the base of the flower, the limen expands in the vertical direction (Fig. 6C, D: li). Its tip turns inwards and becomes covered by the hook-shaped bent operculum (Fig. 6D). Both structures cover the nectar, which originates from the nectar-producing tissue (annulus) below the operculum (Fig. 5F: arrow).

When all elements of the corona are formed, the height of the flower cup is about 340 µm (Table 1). The cia has expanded 4-fold since the first fractionations (Fig. 7A). At anthesis, the radii are 2 cm long, filamentous structures, which are bent backwards and increase the attractiveness of the flower (Fig. 2A). The pali remain much shorter (approx. 0·5 cm) and surround the androgynophore.

Passiflora foetida var. hispida

While P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ has four corona series (two radii, two pali), P. foetida var. hispida forms six rows, two series of radii and four rows of pali. The corona develops in five steps (Fig. 7B).

Stage 1. The cia spans about 150 µm (Table 1), i.e. it is about 50 µm larger than that in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’. The outer radii elements appear (Fig. 8A, B).

Stage 2. The operculum appears as a distinct bulge at the lower margin (Fig. 8C).

Stage 3. The cia has gradually extended and now measures >340 µm in height. The second row of radii and the lowest pali series (row 6) develop almost simultaneously (Fig. 8D, E). The limen starts to grow and the operculum continues bulging.

Stage 4. The second pali series (row 5) is formed above the first one (Fig. 8F). Operculum and limen cover the nectar chamber (arrow).

Stage 5. The last two pali series (rows 4 and 3) appear almost simultaneously (Fig. 7G). After completion of all corona elements, the radii start to elongate (Fig. 7H).

Compared with P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’, the cia is much larger in P. foetida var. hispida (Table 1; Fig. 7A, B). Corona element formation starts when the cup measures approx. 150 µm, i.e. when it is 1·5-fold larger than in the former species. The total extension of the cia is, at approx. 360 µm, much greater than in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ (extension approx. 235 µm). At stage 3, there is space left between the radii and the operculum (approx. 250 µm) which is gradually covered by pali elements. Altogether, fractionation in P. foetida var. hispida proceeds in a convergent pattern, filling the space with radii and pali from both margins of the corona.

Passiflora standleyi

Passiflora standleyi has only three rows of corona elements, one series of radii and two of pali. Nevertheless, five developmental stages can be distinguished.

Stage 1. The cia is formed. It has a similar size to that in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ (approx. 100 µm). Radii appear (Fig. 9A; Table 1).

Stage 2. The operculum develops at the lower margin of the cia (Fig. 9B). In contrast to the two previous species, it is structured from the early beginning.

Stage 3. The upper row of pali appears below the series of radii (Fig. 9C, D: arrow).

Stage 4. The second (lower) row of pali (Fig. 9E: pa) follows immediately. The formation of corona elements is now completed.

Stage 5. In contrast to the previous species, ongoing cia extension (Table 1; Fig. 7) enlarges the operculum zone. As a consequence, the operculum becomes the dominant structure of the corona (Fig. 9F, G). It expands, continues bulging and bending, and ends up as a massive ring (Fig. 9H). As in the other species, the radii elongate to conspicuous elements and the pali remain relatively short.

Passiflora tulae

The corona in P. tulae differs from that in the other species. No rows of radii and pali are formed. Instead, the upper margin of the cia grows out and develops a single conspicuous tube-like structure (Fig. 2D). Nevertheless, four stages of development can be recognized.

Stage 1. The cia is formed as a flat ring. Its upper margin starts growing (Fig. 10A, B).

Stage 2. The operculum separates from the underlying tissue (Fig. 10C).

Stage 3. The operculum forms a ring-shaped constriction and becomes clearly separated from the corona tube (Fig. 10D, E).

Stage 4. While the corona elongates continuously, the operculum starts to grow by bending and folding its surface (Fig. 10F, G). The limen appears below the operculum only at a later stage.

The cia in P. tulae resembles those of P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ and P. stanleyi in both initial dimension (approx. 100 µm) and degree of expansion (Table 1). It differs from them in the size of the first elements, which occupy the whole cia, leaving no space for further corona elements.

DISCUSSION

Passiflora cleary shows that space matters. This is evident in the vegetative plant body, but particularly in the flowers.

In the leaf axils, adaxial accessory buds appear after meristem expansion, when the tendril meristems are dislocated towards the abaxial side. Vegetative branching originates from these accessory buds, while the tendrils give rise to one or two lateral flowers (Troll, 1938–39).

During flower development, space originates from the expansion of the receptacle giving rise to the corona and limen. First, the floral organs are initiated using the existing space completely. Then, the receptacle widens by intercalary meristem activity. A floral cup (hypanthium sensu Ronse de Craene, 2010) originates, separating the sepals and petals from the anthers. From the newly generated space, the corona elements appear. The first step is the formation of an upper rim followed by the bulging of the operculum. These two structures mark the borders of the later corona and are separated from each other by ongoing expansion of the receptacle. The first corona elements appear in a single row slightly differing in shape and size. With expansion, new elements appear at the gaps between two previous elements. The process continues until the whole space is filled. Outside the corona, additional space is provided at the base of the flower when the filaments elongate and the androgynophore rises. Ongoing meristem expansion between the corona and androgynophore provides space for the limen and nectar chamber.

Spatial constraints in expanding meristems

The number of rows depends on the initial size of the cia, the degree of expansion and the relative size of the corona elements.

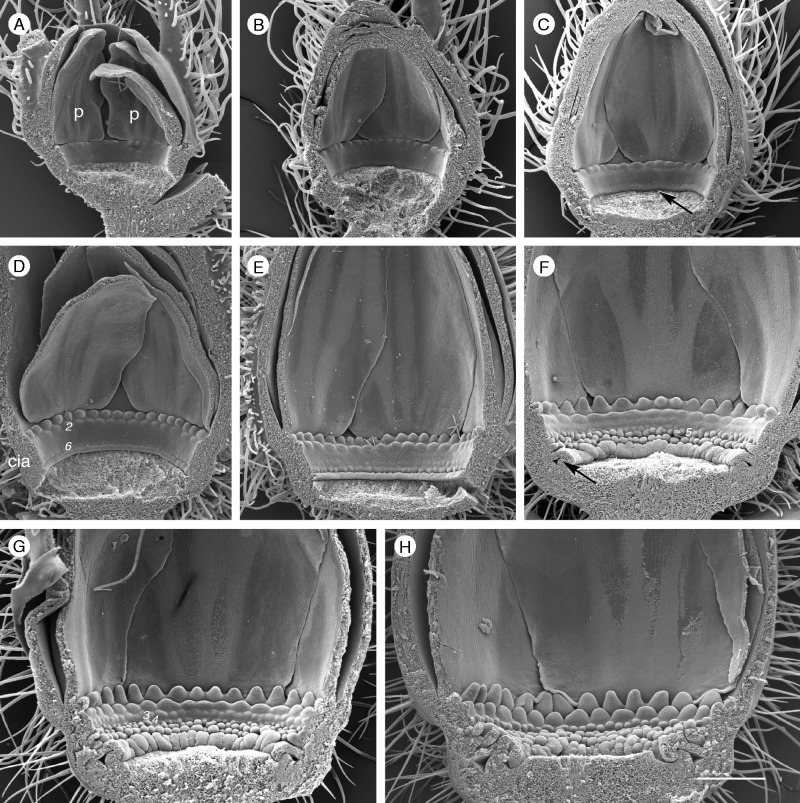

In P. foetida var. hispida, the initial space (approx. 146 µm) and meristem expansion (approx. 360 µm) are highest among the species investigated (Table 1). This correlates with the high number (six) of corona rows. In P. tulae, the initial space (97 µm) and meristem expansion (approx. 235 µm) are lower than in the remaining species. However, the tubular shape of the corona is less the effect of lack of space and more that of different element proportions. The whole cia is used by the upper rim and the massive operculum, leaving no space for additional elements (Fig. 11D, D'). The rim forms a conspicuous tube guiding the hummingbird’s beak to the nectar. A small change in the proportion of the corona elements thus allows the flower to adapt to bird pollination.

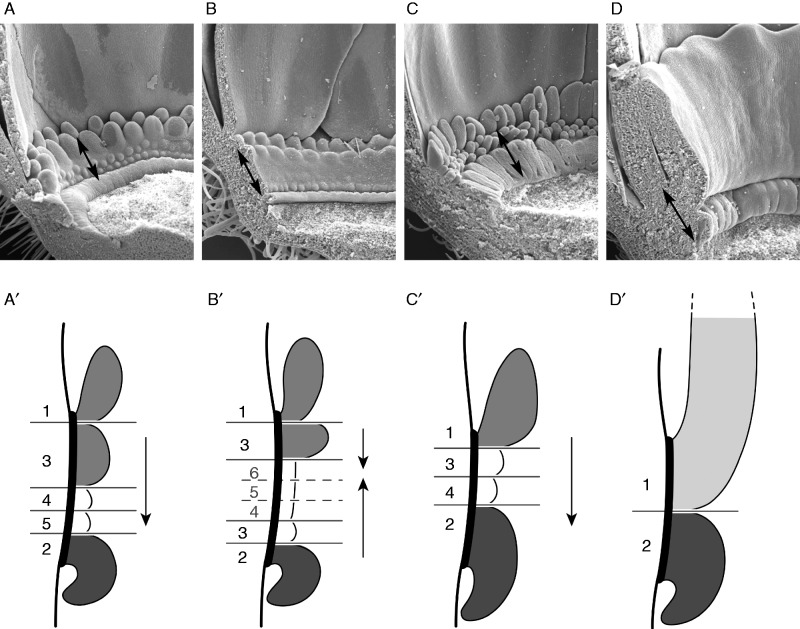

Fig. 11.

Corona element formation as a response to space. (A–D) Corona of the four species at a cup extension of about 340 µm (double arrow, see Table 1). (A'–D') Schematic representation of the same developmental stage showing the relative proportion and use of space of the corona elements. Numbers indicate the sequence of row formation; arrows indicate centripetal (A', C') and convergent (B') direction of fractionation. (A, A') P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’. (B, B') P. foetida var. hispida. (C, C') P. standleyi. (D, D') P. tulae.

As cia and meristem expansion vary among species, a direct comparison of the spatio-temporal conditions during corona formation is difficult. However, in stage 3 (P. foetida var. hispida), 4 (P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’, P. tulae) and 5 (P. stanleyi), the hypanthial cups have a similar size (approx. 340 µm), allowing for comparison of relative proportions and relative occupation of space by the single rows (Fig. 11). At this size, the first series and the operculum are present in all species. In P. tulae (Fig. 11D), the space is completely covered by these two structures, the upper rim giving rise to the corona tube while the operculum forms a massive bulge. In the other three species, space is left for additional corona series, however with different relative proportions. In P. standleyi (Fig. 11C), the single row of radii is well developed, leaving space only for two series of pali. In the two remaining species, a second row of radii is already present. Due to relative proportions, there is more space left in P. foetida var. hispida (Fig. 11B) than in P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ (Fig. 11A), giving rise to four instead of two series of pali.

Fractionation and sequence of corona element formation

It is evident that new corona elements appear as soon as space is made available. In fact, newly generated space appears to stimulate element formation. Thereby, the gaps between existing elements are filled in an apparently autonomous manner. Irregular structures are the result of this space-filling process.

Corona element formation can be explained by the process of fractionation. This process only occurs at determinate meristems (e.g. leaves, flowers) and is defined as the complete use of the existing space (Claßen-Bockhoff and Bull-Hereñu, 2013; Claßen-Bockhoff, 2015). Computational models, based on the concept of directed auxin flow (Reinhardt et al., 2003), clearly show that primordia can arise due to a self-organizing process (Runions et al., 2014). Ongoing meristem expansion changes the spatial conditions and is automatically followed by fractionation. This happens late in ontogeny and results in the formation of novel structures, i.e. ‘organs sui generis’ sensu Masters (1871).

As developing meristems maximize the usage of space by competitive partitioning (Prusinkiewicz and Barbier de Reuille, 2010), fractionation results in diverse patterns. This is also evident in Passiflora. In P. foetida ‘Sanctae Martae’ and P. stanleyi, corona elements are initiated in a centripetal direction, which is consistent with studies in P. edulis and P. quadrangularis (both Moncur, 1988), P. holosericea, P. perakensis, P. molucacana var. glaberrima (all Krosnick et al., 2006) and P. caerulea (Hemingway et al., 2011). In P. foetida var. hispida, in contrast, the three rows of pali are fractionated in the centrifugal direction. Such a convergent pattern was also observed in P. racemosa with three rows of corona elements (Bernhard, 1999) and in P. edulis, P. coccinea and P.‚ Lady Margret’ (Abizza, 2010). These examples and the fact that P. edulis obviously shows both patterns illustrate that the centripetal sequence is not as conserved in Passiflora as assumed (Hemingway et al., 2011).

The reason for the different fractionation patterns is presently unknown. It is possible that the sequence of element formation follows the centripetal or centrifugal expansion of the cia. This would mean that the direction of mitotic activity within the cia differs among species. Alternatively, it could be that the margins of the cia trigger fractionation. In all species, the upper rim and the operculum appear first, limiting the expanding meristem. Wounding experiments in sunflower meristems have shown that primordia can arise from artificially induced margins and proliferate in a self-organizing manner (Hernandez and Palmer, 1988). It is thus plausible that the cia margins themselves trigger fractionation in Passiflora.

The functional interaction between space and morphogenesis is not fully understood. Based on mechanical models (Prusinkiewicz and Barbier de Reuille, 2010) and molecular findings (Hamant et al., 2008), mechanical pressure increases cell wall stress and affects morphogenesis via the microtubule cytoskeleton system. Braam (2005) reports that touch-induced gene expression is widespread in Arabidopsis thaliana, indicating signal transfer between physical force and molecular processes. The newly generated space in Passiflora can be understood as negative mechanical pressure increasing mitotic activity and/or loosening cell walls. It is assumed that meristem widening changes cellular structures and stimulates molecular processes in a similar way to pressure.

Homology of the corona

Homology of the corona in Passiflora has been controversially discussed for almost 200 years. Thereby, anatomical (Puri, 1947, 1948), developmental (Masters, 1871; Bernhard, 1999), systematic (Endress, 1996) and developmental genetic (Hemingway et al., 2011) arguments were used to explain its origin. All the data are worth considering, but only reflect a single aspect of floral complexity.

Puri (1948) followed Lindley (1830) in assuming that the corona originates from sepals and petals. His main argument was the inverted course of the vascular bundles in some corona elements. de Wilde (1974) modified this view in interpreting the corona elements as outgrowths of the receptacle being anatomically influenced by sepals and petals. However, while vascularization was used to corroborate homologies in the past, the belief in vascular conservatism is outdated today (Carlquist, 1969; Schmid, 1972; Bernhard, 1999). According to molecular findings and computational modelling, the development of vascular bundles depends on local auxin accumulation (Reinhardt et al., 2003) and tissue growth (Runions et al., 2005; summarized by Prusinkiewicz and Runions, 2012). Thus, especially in late developing structures, the orientation of bundles should not be overinterpreted (Puri and Agarwal, 1976). As regards the limen, Puri (1948) assumed a staminode origin as he noticed that the limen has five tips in some species alternating with the anthers. Bernhard (1999) illustrated such a limen in P. racemosa; however, in the species investigated here, the limen remains a low fold. It develops late in flower ontogeny as a ring-shaped effiguration of the receptacle and does not show any pentamerous pattern. Developmentally, there is thus no evidence for a staminode origin. Given that the gaps between the young stamens provide most space for limen development, the apparent five tips may be the mere outcome of spatial constraints.

From a systematic point of view, Endress (1996) argued that the corona elements may correspond to a group of modified staminodes. He referred to the closely related family Flacourtiaceae and compared the corona in Passiflora with a polyandrous androecium. However, the present study confirms the view of Bernhard (1999) that the genesis of the corona has almost nothing in common with the development of staminodes or androecia. Corona elements arise much later than the floral organs, appear in irregular numbers without any clear phyllotactic pattern and initiate in some species in a convergent sequence not known from polyandric androecia (Ronse de Craene and Smets, 1992; Ronse de Craene, 2010).

Nevertheless, developmental genetic studies in P. caerulea appear to support the hypothesis of a staminal origin of the corona. Hemingway et al. (2011) found B- and C-class gene expression in all corona elements and the androgynophore of this species and B-class genes in its petals and limen. According to the ABCDE model of floral evolution (Theißen, 2001), B-class gene expression characterizes petals, and B- and C-class gene expression characterizes stamens. Hemingway et al. (2011) preliminarily conclude that the corona might be homologous to stamens while the limen could be a novel structure. This argument raises the question of why gene expression characterizes organ identity in the corona elements but not in the limen. If B-class gene expression in the limen is compatible with its interpretation as a novel structure, why should B- and C-class gene expression not indicate structures ‘sui generis’ in the corona area? Thus, as in Narcissus bulbocodium (Waters et al., 2013), gene expression patterns do not easily explain the homology of the corona.

In the present study, the corona in Passiflora was found to be a novel structure not derived evolutionarily from petals or stamens. Instead, the ancestral flower might have had the capacity to expand during development. Dependent on position and relative timing of expansion and fractionation, different lineages could have evolved. If stamen primordia were affected by expansion, polyandrous flowers would have originated, and if the space between floral organs was widened, additional structures would have appeared. Thus, there is no need to homologize the corona with staminodes, even if related families have a polyandrous androecium. As to the expression of B- and C-class genes in the corona, homology with stamens is also not imperative. Proceeding from a centripetal gradient of floral identity gene expression, B- and C-class genes might be already activated in the hypanthial zone before the corona arises. However, why C-class genes are not expressed in the limen is an unresolved question.

CONCLUSIONS

Passiflora flowers illustrate exciting dynamics during development. After the fractionation of floral organ primordia, intercalary mitotic activity elevates sepals and petals by a hypanthial cup which itself widens and gives rise to the corona. The androgynophore is the outcome of local meristem activity as well as the limen. Thus, all peculiar flower structures are closely correlated with additional growth processes in the developing flower.

Although the developmental dynamics in flowers are well known, the reference system for flower evolution is rather static: a shoot tip of limited growth producing floral leaves and organs in a determinate sequence. Differences from the prototype are explained by heterotopy and heterochrony (Hemingway et al., 2013) without considering time and space as factors on their own, inherent to the system. As long as adult structures are compared, the need for homologizing corona elements with floral organs is evident. However, if the relative timing of element formation during development plays a role, corona elements and anthers are not homologues, and, if the generation of new space has a meaning, the appearance of novel structures should be expected. The study of corona formation in Passiflora thus supports a more dynamic concept of the flower (Claßen-Bockhoff, 2015), integrating molecular, phylogenetical and morphogenetic data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank M. Drews, B. and T. Ulmer, Witten, for providing us with plant material, and H. Bahmann for cultivating the plants in the Botanical Garden at Mainz University. We also gratefully acknowledge stimulating discussion with P. Prusinkiewicz and A. Runions (both Calgary, Canada) and helpful comments by L. Ronse De Craene (Edinburgh) and a second reviewer.

REFERENCES

- Abizza LC. 2010. Desenvolvimento da corona em flores do gênero Passiflora (Passifloraceae). PhD thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas. [Google Scholar]

- Arber A. 1937. Studies in flower structure. III. On the corona and androecium in certain Amaryllidaceae. Annals of Botany 1: 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard A. 1999. Flower structure, development, and systematics in Passifloraceae and Abatia (Flacourtiaceae). International Journal of Plant Science 160: 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Braam J. 2005. In touch: plant responses to mechanical stimuli. New Phytologist 165: 373–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlquist S. 1969. Toward acceptable evolutionary interpretations of floral anatomy. Phytomorphology 19: 332–362. [Google Scholar]

- Čelakovský LJ. 1898. Ueber die Bedeutung und den Ursprung der Paracorolle der Narcisseen. Bulletin international de l’Académie des sciences de Prague 5: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. 1971. Developmental morphology of the flower in Narcissus. Annals of Botany 35: 881–890. [Google Scholar]

- Claßen-Bockhoff R. The shoot concept of the flower: still up to date? Flora. 2015 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Claßen-Bockhoff R, Bull-Hereñu K. 2013. Towards an ontogenetic understanding of inflorescence diversity. Annals of Botany 112: 1523–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler AW. 1875. Blüthendiagramme construirt und erläutert. 1. Leipzig: Theil; (repr. Eppenheim: Koeltz 1954). [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. 1996. Diversity and evolutionary biology of tropical flowers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glück H. 1919. Blatt- und blütenmorphologische Studien. Jena: Fischer. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel K. 1933. Organographie der Pflanzen insbesondere der Archegoniaten und Samenpflanzen, 3rd edn Teil. Jena: Fischer. [Google Scholar]

- Hamant O, Heisler MG, Jönsson H, et al. 2008. Developmental patterning by mechanical signals in Arabidopsis. Science 322: 1650–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway CA, Christensen AR, Malcomber ST. 2011. B- and C-class gene expression during corona development of the blue passionflower (Passiflora caerulea, Passifloraceae). American Journal of Botany 98: 923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez LF, Palmer JH. 1988. Regeneration of the sunflower capitulum after cylindrical wounding of the receptacle. American Journal of Botany 75: 1253–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen DH. 1968. Reproductive behavior in the Passifloraceae and some of its pollinators in central America. Behavior 32: 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick SE, Freudenstein JV. 2005. Monophyly and floral character homology of old world Passiflora (Subgenus Decaloba: Supersection Disemma). Systematic Botany 30: 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick SE, Harris EM, Freudenstein JV. 2006. Patterns of anomalous floral development in the Asian Passiflora (Subgenus Decaloba): supersection Disemma). American Journal of Botany 93: 620–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler EE, King LA. 2004. A brief history of the passionflower. In: Ulmer T, MacDougal JM, Ulmer B, eds. Passiflora – passionflower of the world. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leins P, Erbar C. 2010. Flower and fruit. Morphology, ontogeny, phylogeny, function and ecology. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley J. 1830. An introduction to the natural system of botany. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Masters MT. 1871. XIX.Contributions to the natural history of Passifloraceae. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 27: 593–645. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow AW, Chase MW, Fay MF, Guy CL, Li Q, Zaman FQ. 1999. Systematics of Amaryllidaceae based on cladistic analysis of plastid RBCL and TRNL-F sequence data. American Journal of Botany 86: 1325–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncur MW. 1988. Floral development of tropical and subtropical fruit and nut species. Colllingwood, Australia: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Runions A. 2012. Computational models of plant development and form. New Phytologist 193: 549–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri V. 1947. Studies in floral anatomy IV. Vascular anatomy of the flower of certain species of the Passifloraceae. Botanical Society of America 34: 562–573. [Google Scholar]

- Puri V. 1948. Studies in floral anatomy V. On the structure and nature of the corona in certain species of the Passifloraceae. Journal of the Indian Botanical Society 27: 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Puri V, Agarwal RM. 1976. On accessory floral organs. Journal of the Indian Botanical Society 55: 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Barbier de Reuille P. 2010. Constraints of space in plant development. Journal of Experimental Botany 61: 2117–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt D, Pesce ER, Stieger P, et al. 2003. Regulation of phyllotaxis by polar auxin transport. Nature 426: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP. 2010. Floral diagrams. An aid to understanding flower morphology and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ronse De Craene LP, Smets EF. 1992. Complex polyandry in the Magnoliatae, definition, distribution and systematic value. Nordic Journal of Botany 12: 621–649. [Google Scholar]

- Runions A, Fuhrer M, Lane B, Federl P, Rolland-Lagan AG, Prusinkiewicz P. 2005. Modeling and visualization of leaf venation patterns. ACM Transactions on Graphics 24: 702−711. [Google Scholar]

- Runions A, Smith RS, Prusinkiewicz P. 2014. Computational models of auxin-driven development. In: Zažímalová E, Petrášek J, Benkova E, eds. Auxin and its role in plant development. Heidelberg: Springer, 315–357. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeppi H. 1939. Vergleichend-morphologische Untersuchungen an den Staubblättern der Monokotyledonen. Nova Acta Leopoldina (N.F.) 6: 389–447. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid R. 1972. Floral bundle fusion and vascular conservatism. Taxon 21: 429–446. [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. 1972. Floral morphology of the Amaryllidaceae. I. Subfamily Amaryllidioideae. Canadian Journal of Botany 50: 1555–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Theissen G. 2001. Development of floral organ identity: stories from the MADS house. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 4: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troll W. 1938–39. Vergleichende Morphologie der höheren Pflanzen. 1, Band 2. Teil. Berlin: Borntraeger. [Google Scholar]

- Velenovský J. 1910. Vergleichende Morphologie der Pflanzen. 3. Teil: Die Morphologie der Blüte der Phanerogamen. Prag. [Google Scholar]

- Waters MT, Tiley AMM, Kramer EM, Meerow AW, Langdale JA, Scotland RW. 2013. The corona of the daffodil Narcissus bulbocodium shares stamen-like identity and is distinct from the orthodox floral whorls. The Plant Journal 74: 615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde WJ. 1974. The genera of tribe Passifloreae (Passifloraceae) with special reference to flower morphology. Blumea 22: 37–50. [Google Scholar]