Abstract

Purpose

To assess content validity and patient and provider prioritization of Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression, Anxiety, Fatigue, and Alcohol Use items in the context of clinical care for people living with HIV (PLWH), and to develop and assess new items as needed.

Methods

We conducted concept elicitation interviews (n=161), item pool matching, prioritization focus groups (n=227 participants), and cognitive interviews (n=48) with English-speaking (~75%) and Spanish-speaking (~25%) PLWH from clinical sites in Seattle, San Diego, Birmingham, and Boston. For each domain we also conducted item review and prioritization with two HIV provider panels of 3 to 8 members each.

Results

Among items most highly prioritized by PLWH and providers were those that included information regarding personal impacts of the concept being assessed, in addition to severity level. Items that addressed impact were considered most actionable for clinical care. We developed additional items addressing this. For depression we developed items related to suicide and other forms of self-harm, and for all domains we developed items addressing impacts PLWH and/or providers indicated were particularly relevant to clinical care. Across the 4 domains, 16 new items were retained for further psychometric testing.

Conclusion

PLWH and providers had priorities for what they believed providers should know to provide optimal care for PLWH. Incorporation of these priorities into clinical assessments used in clinical care of PLWH may facilitate patient-centered care.

Background

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are increasingly assessed in routine clinical care (1–3). While a few PRO instruments have been designed specifically for this application (4–6), many were designed for group-level comparisons in clinical trials or observational studies rather than for clinical care of individual patients. Several specific characteristics are desirable for a PRO instrument used in clinical care of individual patients: 1) The instrument domains should be highly valued by patients and/or providers for use in clinical care (7); 2) If scores are to be used, the instrument should have acceptable psychometric characteristics to facilitate valid, reliable, and interpretable patient-level measurement (8); 3) Items should be clearly understood by patients, and should include content that ensures that providers obtain clinically important information valued for clinical care beyond just quantitative assessment of domain level or severity and; 4) At the same time, patient and clinic burden should be minimized as much as possible.

Depression, anxiety, fatigue, and alcohol use are common issues of importance for people living with HIV (PLWH) (9). We describe an assessment of PLWH and provider priorities in relation to Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression, Anxiety, Fatigue, and Alcohol Use items in the context of clinical care for PLWH. PROMIS is a multi-year effort funded by the National Institutes of Health to create item banks for assessing patient-reported health areas across diseases and chronic conditions (www.nihpromis.org). This research was conducted in a large, heterogeneous sample of PLWH recruited from four Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) clinical sites distributed across the United States. We included Spanish-speaking, as well as racially diverse English-speaking PLWH in the study.

Key issues to consider in assessing a PRO instrument’s content validity are its intended purpose and context of use (10). In this study, the intended purpose of the measures assessed was to provide useful information for delivering clinical care. With this in mind, for each domain, we asked PLWH and providers what patient-reported information was most important for providers to know to provide optimal clinical care to PLWH. We focus on understandability of item content and on ensuring that specific, highly clinically relevant content identified by PLWH and providers will be available for consideration when evaluating potential modifications to PROMIS instruments to improve their value for clinical care of PLWH.

Methods

Participant recruitment and enrollment

We recruited English-speaking participants from three CNICS sites: University of Washington - Madison Clinic (Seattle), University of Alabama at Birmingham - 1917 Clinic (Birmingham), and the Fenway Clinic (Boston). We recruited Spanish-speaking participants from the University of California – San Diego (UCSD) and the University of Washington Madison Clinic. To increase the numbers of Spanish-speaking participants, we also recruited from Entre Hermanos, a Seattle-area Latino-serving community-based agency. We performed purposeful oversampling of African American and Hispanics/Latino individuals to enhance diversity. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at each site approved all study procedures.

PLWH were approached based on results of a web-based self-administered PRO assessment at the time of routine clinic visits. The PRO assessment was specifically developed for measurement of PROs for the CNICS network for both clinical research and clinical care (11, 12). Since 2006–2009 (year of initiation varies by site), consenting PLWH have completed PRO assessments prior to routine physician visits at approximately 6-month intervals with >10,000 PLWH having completed ~45,000 clinical assessments to date. PLWH who do not speak English or Spanish, who are acutely ill or who are intoxicated or have obvious cognitive impairment are not asked to complete the assessment. PLWH answer instruments from several health domains including depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (PHQ-5), alcohol use (AUDIT-C), and several others, including an HIV symptom index containing an item measuring fatigue (13–17). PLWH scoring above threshold levels for the target domains (depression, fatigue, etc.) were recruited by research staff for study participation after their appointment, either in-person at the clinic or by telephone. We provide details of the scoring thresholds below and in Table 1. PLWH who met eligibility criteria and were interested in participating had study procedures explained to them and informed written or oral consent was obtained, depending upon the study site IRB’s requirements. Participants received a $25 reimbursement as a thank you for their participation in concept elicitation interviews and focus groups and $15 for participation in cognitive interviews.

Table 1.

PLWH Group Definitions and Sample Sizes by Domain (n=436)

| Domain | Instrument | Severity Definitions | Concept Elicitation Interview n | Focus Group n | Cognitive Interview n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | Mild = 5–9 | 14 | 13 | 0 |

| Moderate = 10–19 | 11 | 25 | 3 | ||

| High = 20 or higher | 9 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Total | 34 | 51 | 5 | ||

|

| |||||

| Anxiety | Patient Health Questionnaire-5 (PHQ-5) | Anxiety Only = Endorse screener and 0–3 follow-up items | 22 | 24 | 6 |

| Anxiety Plus Panic = Endorse screener and all 4 follow-up items | 19 | 29 | 4 | ||

| Total | 41 | 53 | 10 | ||

|

| |||||

| Fatigue | HIV Symptom Index item | Mild = ‘Have fatigue which doesn’t bother you’ or ‘Bother you a little’ | 17 | 29 | 11 |

| Moderate/High = ‘Have fatigue which bothers you some’ or ‘Bothers you a lot’ | 25 | 39 | 10 | ||

| Total | 42 | 68 | 21 | ||

|

| |||||

| Alcohol Use | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) | At-risk = 4–7 | 21 | 29 | 0 |

| Highly at-risk = 8–12 | 23 | 26 | 12 | ||

| Total | 44 | 55 | 12 | ||

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

1) English or Spanish-speaking, 2) 18 years or older, 3) HIV-infected. PLWH were excluded if they were cognitively unable to complete the PRO assessment or if they were unwilling to consent to study participation.

Study design and procedures

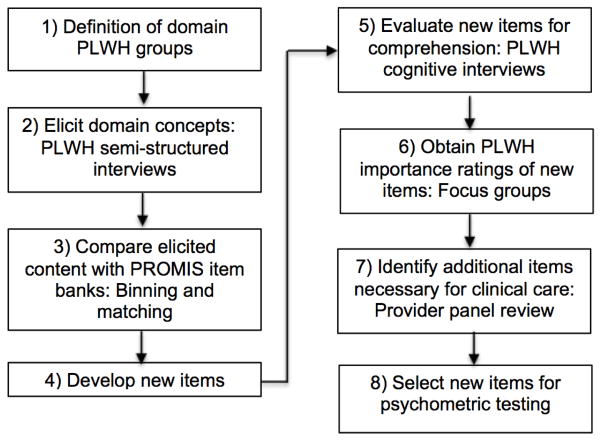

Seven steps guided the work conducted. A description of each step and a flowchart of study activities can be found below (Figure 1). Generally, all steps were completed in serial order for the Depression, Anxiety, Fatigue, and Alcohol Use domains respectively.

Figure 1.

Procedure Steps

Step 1: Definition of domain PLWH groups

To ensure broad representation of PLWH across severity levels for each domain, we defined severity levels for each domain as assessed by the clinical assessment and then selected PLWH for each severity level for concept elicitation interviews and focus groups (Table 1).

Step 2: Elicit domain concepts

We conducted 34–44 concept elicitation interviews with English-speaking (75%) and Spanish-speaking (25%) PLWH for each of the four domains. We developed semi-structured interview guides including probes asking about the clinical importance of concepts for each domain. For example, the Alcohol Use interview guide included probes related to drinking patterns, cue-based drinking, cravings to drink, and efforts to control drinking. The PROMIS Alcohol item bank includes banks addressing Positive Consequences, Negative Consequences, Positive Expectancies, and Negative Expectancies; we focused exclusively on the Alcohol Use bank as most relevant for clinical care based on input received from HIV providers after reviewing all of the alcohol banks. We asked interviewees about their experience with the domain and what they thought was most important for providers to know about in relation to it. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded, transcribed by a professional service (VerbalInk.com), and then uploaded into a qualitative analysis database (ATLAS.ti). Quality review of interview audio-files was conducted within seven business days from the date of the initial interviews, to ensure interviewers were following best practices. We conducted interviews until concept saturation was reached, which we defined as the point at which no new concepts were found over three consecutive interviews. Across the sites and domains, a total of 12 research investigators and staff conducted interviews and were trained by Dr. Edwards who has extensive experience using these techniques. {Edwards et al., 2002, #100026; Edwards et al., 2005, #11702; Goss et al., 2009, #74553; Balakrishnan et al., 2012, #6160}. Interviewers were instructed in the interview purpose and procedures before practicing the procedures through role-playing and feedback prior to conducting actual interviews. They were also given constructive feedback based on the audio-recordings of the study interviews they conducted.

Step 3: Compare elicited content with PROMIS item banks

Pairs of investigators working independently identified interview text relevant for each domain. The pairs of investigators then independently attempted to match this text to existing PROMIS item banks, augmented by items excluded from item banks developed in the first phase of PROMIS (18). Coders met regularly to discuss and resolve coding discrepancies, and in cases where they could not reach agreement the discrepancy was reviewed and resolved by the content study team as a whole.

Step 4: Develop new items

We crafted new items based on content identified by PLWH as important for clinical care but not currently included in the PROMIS item banks. New items were crafted following the same principles as those used in PROMIS previously for any newly crafted item (18), as well as other long-established principles for item writing (19). The research team reviewed the new items using the PROMIS Qualitative Item Review (QIR) criteria, and modified them where necessary. QIR is a process whereby items are evaluated for redundancy, face validity, and inconsistent relationship to the target domain (18).

We assessed newly crafted items for readability using the Lexile Analyzer; we modified language until each newly crafted item had a 6th grade reading level (900L) or lower using shorter sentences or more frequently used words. We also assessed newly crafted items for translatability, and then translated them into English or Spanish, depending upon the language from which they originated (20).

Step 5: Evaluate new items for comprehension

For each domain we enrolled ~10 PLWH stratified by severity level (Table 1) and asked them to participate in cognitive debriefing interviews about the newly crafted items. Upon completing the items, we conducted a short debriefing interview with each participant aimed at assessing cognitive attributes of the items. We used standard procedures developed at the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics Cognitive Survey Laboratory (21, 22) in the debriefing process. The interview questions focused on item comprehension (item intent, meaning of terms), retrieval from memory (recall of information, recall strategy), decision processes (motivation, sensitivity/social desirability), and response processes (mapping of response to response options) (23). The cognitive debriefing process occurred in three steps: 1) we performed cognitive interviews with PLWH who had completed the initial draft items, 2) we revised the items based on the initial cognitive interviewing results, and 3) we had additional PLWH complete the revised items and performed cognitive interviews, and then we made any final item revisions. All interview guides can be downloaded from http://depts.washington.edu/seaqol/docs/interview-guides.pdf.

Step 6: Obtain PLWH importance ratings of new items

We convened PLWH in groups by domain severity level (Table 1) and asked individuals within these groups to rate the clinical importance of all existing PROMIS item bank items and new items that were created. PLWH individually sorted items written on cards into three stacks identifying those they considered ‘definitely important’ for clinical care, those that were ‘somewhat important’, and those that were ‘not important’. PLWH were free to allocate items across these categories as they wished. We compiled these selections and displayed and reviewed aggregate results as a group. In focus group fashion, we asked participants to discuss specific reasons why they selected the items they considered most important for clinical care. After this, we asked the PLWH to review their individual selections a final time, making any additions or deletions they wished. The focus group discussions of specific reasons why some items were considered important for clinical care were audio-recorded and transcribed for extraction of illustrative quotes. We included English-speaking (75%) and Spanish-speaking (25%) focus groups for each domain.

Step 7: Identify additional items necessary for clinical care

We convened provider panels to review and evaluate items in terms of their potential usefulness in clinical care. Our provider panels included HIV primary care providers, HIV mental health providers including psychiatrists and psychologists, HIV clinical, translational and basic researchers including CNICS site principal investigators and AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) investigators, and HIV clinic medical directors. For each of the domains, we assembled provider panels, either in-person or using webinars, to prioritize item content for potential importance for clinical care beyond reliable assessment of domain level alone. Providers reviewed the entire list of items, as well as subsets of items such as those that would be seen in a short form or a computer adaptive test based on various severity levels looking for gaps in content, appropriateness of the content for the domain of interest, relevance of the items and the domain itself for clinical care, and other concerns. We conducted at least two provider panels of 3 to 8 members from at least two sites for each domain.

Step 8: Select new items for psychometric testing

To decide which new items to retain for psychometric testing, we considered equally: 1) PLWH item importance ratings (Step 6), and 2) clinician identification of additional items necessary for clinical care (Step 7).

Results

Sample characteristics

Across all four domains and level of domain severity (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) (Step 1), 161 PLWH participated in concept elicitation interviews, and 227 participated in focus groups (Table 1). A total of 48 PLWH also participated in cognitive interviews.

Of PLWH participating in the concept elicitation interviews and item prioritization groups, a majority were 30–49 years old, male, and self-reported White race, although sizeable proportions were African American (23%) or Hispanic (42%), reflecting our purposeful oversampling. Most had CD4 counts of 350 cells/ml3 or greater, had been diagnosed 11 or more years ago, and route of HIV transmission was through men having sex with men (MSM) (Table 2). These proportions were similar across the four domains and between English and Spanish-Speaking participants. Of those participating in cognitive interviews, 79% were male, 35% Hispanic, 15% African-American, and 46% White.

Table 2.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Concept Elicitation and Item Prioritization Participants (PLWH)

| Combined (n=396) n (%) | English (n=243) n (%) | Spanish (n=153) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | |||

| 18–29 | 23 (5.8) | 15 (6.1) | 8 (5.2) |

| 30–49 | 262 (66.2) | 151 (62.1) | 111 (72.5) |

| 50+ | 111 (28.0) | 77 (31.7) | 34 (22.2) |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 103 (26.0) | 68 (28.0) | 35 (22.9) |

| Male | 293 (74.0) | 175 (72.0) | 118 (77.1) |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity (self-reported) | |||

| African-American | 92 (23.2) | 92 (37.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 128 (32.3) | 128 (52.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 167 (42.2) | 14 (5.8) | 153 (100.0) |

| Other | 9 (2.3) | 9 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| |||

| CD4 Count (cells/ml3) (Current) | |||

| 0–199 | 38 (9.6) | 27 (11.1) | 11 (7.2) |

| 200–349 | 70 (17.7) | 46 (18.9) | 24 (15.7) |

| 350+ | 281 (71.0) | 169 (69.5) | 112 (73.2) |

| Missing or Unknown | 7 (1.8) | 1 (0.0) | 6 (3.9) |

|

| |||

| Time Since Diagnosis (Years) | |||

| 0–1 | 23 (5.8) | 14 (5.8) | 9 (5.9) |

| 2–5 | 78 (19.7) | 40 (16.5) | 38 (24.8) |

| 6–10 | 98 (24.7) | 61 (25.1) | 37 (24.2) |

| 11+ | 194 (49.0) | 127 (52.3) | 67 (43.8) |

| Missing or Unknown | 3 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) |

|

| |||

| Route of Transmission | |||

| Men Who Have Sex with Men | 238 (60.1) | 139 (57.2) | 99 (64.7) |

| Intravenous Drugs | 25 (6.3) | 19 (7.8) | 6 (3.9) |

| Heterosexual | 93 (23.5) | 60 (24.7) | 33 (21.6) |

| Other or Missing | 40 (10.1) | 25 (10.3) | 15 (9.8) |

Depression domain

As a result of concept elicitation interviews, we generated a total of 38 concepts, 28 that were found in the PROMIS item bank and 10 that were not (Step 2). The new items we developed representing the concepts not found in the item bank are: 1) I felt more irritable than usual, 2) I got tired easily, 3) I thought about killing myself, 4) I felt so bad that I did things that I knew would hurt me, 5) I felt dead inside, 6) I felt desperate to escape how I feel, 7) I felt less interested than usual in sex, 8) I felt no energy to do things, 9) I felt bothered by things that don’t usually bother me, and 10) I felt that others would be better off if I were dead (Steps 3–4). We did not make wording changes in the new depression items as a result of cognitive interviewing as we did not discover any comprehension problems (Step 5).

There were two items from the PROMIS item bank that were most frequently selected by PLWH as definitely important for clinical care (selected by 53% of PLWH), ‘I felt I had no reason for living’ and ‘I felt that I wanted to give up on everything’. While both of these items reflect high levels of depression, many PLWH and all of the providers identified additional items important for clinical care that included more explicit indications of suicidal ideation and other forms of self-harm. We selected two of the new items to address this: ‘I thought about killing myself’ (selected as ‘definitely important’ by 51% of PLWH) and ‘I felt so bad that I did things that I knew would hurt me’ (43%). We selected a third new item to address feelings of desperation: ‘I felt desperate to escape how I feel’ (43%) (Step 6). Described by one PLWH: “I don’t feel like I wanna kill myself but I want to escape how I feel” (UAB1). The clinical importance of this state of mind is evident: “I knew all about drugs, but I said what the hell? [I’m] gonna be dead in two years, what does it matter?” (UAB1) Providers were interested in overall depression and did not identify specific item content as necessary for clinical care with the exception of suicidal ideation and ensuring that mania was assessed before initiating depression treatment (Step 7).

The new depression items we selected for psychometric testing are: 1) I thought about killing myself, 2) I felt desperate to escape how I feel, and 3) I felt so bad that I did things that I knew would hurt me (Table 7, Step 8). This included all of the items rated as definitely important by PLWH (Table 3, Step 6).

Table 7.

New Items Selected for Psychometric Testing by Domain (n=16 Total)

| Domain | In the past 7 days… |

|---|---|

| Depression |

|

| Anxiety |

|

| Fatigue |

|

| Alcohol Use |

|

Table 3.

Depression - % PLWH Selected Item as ‘Definitely Important’ for Clinical Care (English and Spanish Combined n=51)

| 53 | I felt I had no reason for living |

| 53 | I felt that I wanted to give up on everything |

| 51 | I thought about killing myself* |

| 45 | I felt depressed |

| 43 | I felt so bad that I did things that I knew would hurt me* |

| 43 | I felt desperate to escape how I feel* |

| 41 | I felt emotionally exhausted |

New items developed in this study based on PLWH concept elicitation interviews. Other items are from the PROMIS Depression item bank.

Anxiety domain

Patient concept elicitation interviews resulted in a total of 45 concepts, 29 that were found in the PROMIS item bank and 16 that were not (Step 2). The new items we developed representing the concepts not found in the item bank are: 1) Because of my anxiety I felt sudden changes in my body temperature, 2) Because of my anxiety I had racing thoughts, 3) I felt stressed out, 4) Because of my anxiety I felt pressure on my chest, 5) I felt paranoid, 6) Because of my anxiety I felt out of control, 7) Because of my anxiety I felt like I was going to pass out, 8) Because of my anxiety I felt dizzy, 9) Because of my anxiety I did not want to be around other people, 10) Because of my anxiety I ate more/less than usual, 11) Because of my anxiety I felt desperate, 12) I found it difficult to sit still, 13) I had trouble concentrating, 14) I was afraid to leave my house, 15) I had unpleasant thoughts that would not leave my mind, and 16) Because of my anxiety I had trouble breathing (Steps 3–4). As a result of cognitive interviewing, we added the attribution “Because of my anxiety” to several of the items (Step 5).

PLWH identified anxiety-related somatic symptoms and perceived need for care because of anxiety as definitely important for clinical care (Step 6). By far the most often-selected anxiety item was: “I felt like I needed help for my anxiety” (selected by 60% of the PLWH). Another frequently selected item was having difficulty sleeping (50%). Based on concept elicitation interviews with PLWH, we selected new items assessing anxiety-related somatic symptoms: feelings of passing out (44%), trouble breathing (40%), and chest pressure (40%).

Provider discussion focused on the benefit of understanding whether anxiety is interfering with daily life or is disruptive to daily activity (Step 7). Providers believed this strategy would indicate anxiety severity or importance and also assist in determining whether the condition needed to be addressed. Providers expressed the view that measuring impact of anxiety was as important as measuring anxiety severity level.

The new anxiety items we selected for psychometric testing are: 1) Because of my anxiety I had trouble breathing, 2) Because of my anxiety I felt pressure on my chest, and 3) Because of my anxiety I felt like I was going to pass out (Table 7, Step 8). This included all of the items rated as definitely important by PLWH, with the exception of, “I had unpleasant thoughts that would not leave my mind” (Table 4, Step 6).

Table 4.

Anxiety - % PLWH Selected Item as ‘Definitely Important’ for Clinical Care (English and Spanish Combined n=53)

| 60 | I felt like I needed help for my anxiety |

| 50 | I had difficulty sleeping because of my anxiety |

| 50 | I had sudden feelings of panic |

| 46 | I felt anxious |

| 46 | I had unpleasant thoughts that would not leave my mind* |

| 44 | Because of my anxiety I felt like I was going to pass out* |

| 40 | Because of my anxiety I had trouble breathing* |

| 40 | Because of my anxiety I felt pressure on my chest* |

New items developed in this study based on PLWH concept elicitation interviews. Other items are from the PROMIS Anxiety item bank.

Fatigue domain

Patient concept elicitation interviews generated a total of 43 concepts, 33 that were found in the PROMIS item bank and 10 that were not (Step 2). The new items we developed representing the concepts not found in the item bank are: 1) How often did you wake up feeling exhausted?, 2) How often did you feel so worn out that you stayed in bed all day?, 3) How often were you too exhausted to take your medication?, 4) How often were you too tired to carry out your daily responsibilities?, 5) How often did your body feel exhausted?, 6) How often were you so tired that you made mistakes?, 7) How often were you so exhausted that you missed appointments?, 8) How often were you so tired that everything was an effort?, 9) How often were you too tired to be around other people?, and 10) How often were you too tired to pay attention to important things? (Steps 3–4). As a result of cognitive interviewing, we changed the word “tired” to “exhausted” for the new items #3 and #7 above. We also re-worded new item #5 from “How often was your body exhausted?” to “How often did your body feel exhausted?” (Step 5).

PLWH felt that fatigue items were needed that addressed not only fatigue level, but also the impact of fatigue on patient self-care (Step 6). Two of the newly-developed items considered important by PLWH directly related to fatigue interfering with successful care of their medical condition: 1) “How often were you too exhausted to take your medication?” (selected by 50% of PLWH as definitely important for clinical care) and 2) “How often were you so exhausted that you missed appointments?” (28%). One PLWH described how fatigue affects ability to attend clinic appointments as: “You have just enough [energy] to maybe get up, make yourself something to eat. If that’s your fatigue level, coming to a [clinic] appointment is a marathon.” (UW3) Other commonly selected fatigue items included impairment of social functioning and being bothered by fatigue: “It’s not that you normally are a person that doesn’t like to be around other people or spend time with other people. It’s that your fatigue has gotten to a level that it’s too much effort.” (UAB2) PLWH also discussed how fatigue can lead to a reduction in physical activity: “I thought it was important for me to let my doctor know hey, I’m not really doing my (exercise) routine because my body feels exhausted.” (FHC1) Providers were predominantly interested in fatigue severity and to some extent fatigue impact and not otherwise interested in specific fatigue content (Step 7).

The new fatigue items we selected for psychometric testing are: 1) How often did you wake up feeling exhausted?, 2) How often were you too exhausted to take your medication?, 3) How often did your body feel exhausted?, and 4) How often were you so exhausted that you missed appointments? (Table 7, Step 8). This included all of the items rated as definitely important by PLWH (Table 5, Step 6).

Table 5.

Fatigue - % PLWH Selected Item as ‘Definitely Important’ for Clinical Care (English and Spanish Combined n=68)

| 50 | How often were you too exhausted to take your medication?* |

| 31 | To what degree did your fatigue interfere with your physical functioning? |

| 28 | How often did you feel tired? |

| 28 | To what degree did you have to force yourself to get up and do things because of your fatigue? |

| 28 | How often were you bothered by your fatigue? |

| 28 | How often did you wake up feeling exhausted?* |

| 28 | How often did your body feel exhausted?* |

| 28 | How often were you so exhausted that you missed appointments?* |

New items developed in this study based on PLWH concept elicitation interviews. Other items are from the PROMIS Fatigue item bank.

Alcohol Use domain

Patient concept elicitation interviews generated a total of 44 concepts, 37 that were found in the PROMIS Alcohol Use item bank and 7 that were not (Step 2). The new items we developed representing the concepts not found in the item bank are: 1) I drank because I felt stressed, 2) I drank until I got sick, 3) I drank to avoid my problems, 4) I had to drink more to get the same effect I used to get, 5) I drank until I passed out, 6) I drank so much that I could not remember what happened while I was drinking, and 7) I was worried about how drinking was affecting my health (Steps 3–4). We did not make wording changes in the new alcohol use items as a result of cognitive interviewing as we did not discover any comprehension problems (Step 5).

PLWH believed it important for providers to know about the causes and impacts of alcohol use in addition to the level of use itself so that potential causes of excessive alcohol use could be addressed in treatment (Step 6). The most commonly selected Alcohol Use item was: “I was worried about how drinking was affecting my health”, selected by 73% of PLWH. Other frequently selected items related to impacts of drinking too much alcohol: memory loss (56%), passing out (56%), and getting sick (55%). The importance of these types of items was expressed by one PLWH this way:

“I think some of the similar questions like I drank so much I could pass out. Or I drank until I got sick, or something where you’re actually binging or doing something a little more health related… I think that would be a little more useful.” (UW2)

Drinking to avoid problems was also frequently selected as important (51%) and was described as a way for providers to know how best to address the problem:

“…it would be a good thing for your doctor to know that you have been drinking a lot and that you’re all stressed out, and that’s the reason why you’re doing it. You have problems, and you think the alcohol is going to make it better.” (UW2)

Finally, PLWH expressed that having trouble controlling one’s drinking was important to assess (35%), as described by this PLWH: “…help identify those who understand that they need to stop drinking but are unable to control themselves…” (UCSD4).

Providers believed it was important to know about the level of alcohol use (Step 7). In addition, some providers also wanted to know about negative consequences of alcohol use to initiate discussions with PLWH. There was not agreement as to this point; some providers expressed that this specific content would be valuable for clinical care and others expressed that there was not specific content above level of use that would be of value. Discussions for this domain were the most discordant between the providers.

The new alcohol use items we selected for psychometric testing are: 1) I drank until I got sick, 2) I drank to avoid my problems, 3) I had to drink more to get the same effect I used to get, 4) I drank until I passed out, 5) I drank so much that I could not remember what happened while I was drinking, and 6) I was worried about how drinking was affecting my health (Table 7, Step 8). This included all of the items rated as definitely important by PLWH (Table 6, Step 6).

Table 6.

Alcohol Use - % PLWH Selected Item as ‘Definitely Important’ for Clinical Care (English and Spanish Combined n=55)

| 73 | I was worried about how drinking was affecting my health* |

| 56 | I drank so much that I could not remember what happened while I was drinking* |

| 56 | I drank until I passed out* |

| 55 | I drank until I got sick* |

| 51 | I drank to avoid my problems* |

| 38 | I used alcohol and other drugs together, to get high |

| 35 | I had trouble controlling my drinking |

| 35 | I had to drink more to get the same effect I used to get* |

New items developed in this study based on PLWH concept elicitation interviews. Other items are from the PROMIS Alcohol Use item bank.

Discussion

We found that existing PROMIS depression, anxiety, fatigue, and alcohol use items considered most important for clinical care by PLWH and providers were those that provided information regarding the impacts of these domains on PLWH’ lives. We created new items addressing suicidal ideation and self-harm, somatic and cognitive impacts of anxiety, and clinically-related impacts of fatigue and alcohol use. These were issues highly prioritized by PLWH and providers as important for clinical care but not currently included in the PROMIS item banks. PLWH and providers clearly articulated why they considered some items of high importance for clinical care, beyond their contribution to measuring the level of the domain in question. We found there was a relatively high level of consensus regarding the items PLWH considered important for clinical care, with the exception of the fatigue domain.

An important aspect of establishing content validity is considering an instrument’s context of use (10), in our case the clinical care context was a paramount consideration. Other studies examining PROs used in clinical care have also found important content to be lacking for clinical care (24, 25). Harley et al. (24) found that the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core instrument plus disease-specific modules lacked symptom issues commonly discussed by cancer patients. Snyder et al. (25) concluded that a barrier to uptake of PROs in clinical practice is varying levels of item relevance across different patient groups. Finally, Greenhalgh concluded that the extent to which PROs affect clinician behavior is largely determined by the ways in which instruments fit or do not fit into the routine manner in which patients and clinicians communicate with one another and how clinicians go about making treatment decisions vis-à-vis their patients’ perspectives (26). It seems clear that PROs used in clinical care have content requirements that are to some degree different than those used in other contexts, including clinical trials and observational studies.

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted in the context of one particular clinical population, PLWH, so generalizability to people with other conditions is unclear. Nevertheless, the concepts that came up were not HIV-specific. The new items we developed do not refer to HIV and may be relevant in other patient populations as well. We took pains to ensure that new items we developed met PROMIS’s item development criteria. Another limitation is that item development occurred in English and Spanish languages only. In addition, the Spanish-speakers in this study were largely of Mexican origin. Spanish speakers of other national origins may differ in important ways in their views and language use. We hope that others will continue this work in other languages and with Spanish speakers from other parts of the world. Also, while we included both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking PLWH, we did not include enough of each group to reliably examine item prioritization results separately. Our objective was to capture the perspectives of both Spanish and English speakers in the overall results. A strength of the study is that it included a diverse sample of PLWH and providers from across the United States to participate in an in-depth evaluation of PROMIS items in the context of clinical care. The study’s focus on the context of clinical care is also a strength as few studies have considered the content validity of PRO items in this context, despite the increasing use of these items in clinical care.

This study demonstrates that PLWH and their care providers perceive a need for more context-appropriate targeted PROs in clinical care. In particular, items measuring potentially actionable issues related to causes and impacts of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and alcohol use were desired. Patient-centered qualitative research specific to measurement purpose and context of PRO use will likely enhance the success of PROs integrated in clinical practice. Careful consideration of the priorities of PLWH and providers will strengthen the value of PRO collection in routine clinical care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our study participants who so generously shared their time and insights with us, and also our PROMIS Network colleagues, Paul Pilkonis and Kevin Weinfurt, for their valuable advice and guidance. We would also like to acknowledge our research coordinators, data managers, and interviewers who were instrumental in carrying out the study: Joel Aguirre, Erika Austin, Nelly Ayala, Scott Batey, Tyler Brown, Anna Church, Paul Crawford, Lydia Dant, Gina Denoble, Chris Grasso, Niko Lazarakis, Edgar Paez, and Melonie Walcott. We would especially like to thank our past project manager, Anne Skalicky, who was instrumental in commencing and carrying out this research.

Funding: This research was funded by a cooperative agreement awarded to the University of Washington (Principal Investigators: D Patrick, H Crane, P Crane) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) (grant #U01 AR 057954). Support was also provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (grant #P30 AI027757) and CNICS (R24 AI067039) and National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (ARCH grants U01 AA020802, U01 AA020793 and U24 AA020801).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have conflicts of interest to report associated with this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Todd C. Edwards, 1208 NE 43rd St., Seattle, WA 98195.

Rob J. Fredericksen, 325 9th Avenue, Seattle, WA, 98104.

Heidi M. Crane, 325 9th Avenue, Seattle, WA, 98104.

Paul K. Crane, Room 1450, Ninth and Jefferson Building, Seattle, WA, 98104.

Mari M. Kitahata, 325 9th Avenue, Seattle, WA, 98104.

William C. Matthews, 4168 Front St, San Diego, CA 92103.

Kenneth H. Mayer, 1340 Boylston Street, Boston, MA 02215.

Leo S. Morales, 1959 NE Pacific St. HSC A-300, Seattle, WA 98195.

Michael J. Mugavero, 908 20th Street S, Suite 250, Birmingham, AL 35205.

Rosa Solorio, 1208 NE 43rd St., Seattle, WA 98195.

Frances M. Yang, 1459 Laney Walker Blvd, Augusta, GA 30901.

Donald L. Patrick, 1208 NE 43rd St., Seattle, WA 98195.

References

- 1.Jensen RE, Rothrock NE, DeWitt EM, et al. The Role of Technical Advances in the Adoption and Integration of Patient-reported Outcomes in Clinical Care. Med Care. 2015;53:153–159. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozak MS, Mugavero MJ, Ye J, et al. Patient reported outcomes in routine care: advancing data capture for HIV cohort research. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:141–147. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21:1305–1314. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haroutiunian S, Donaldson G, Yu J, Lipman AG. Development and validation of shortened, restructured Treatment Outcomes in Pain Survey instrument (the S-TOPS) for assessment of individual pain patients’ health-related quality of life. Pain. 2012;153:1593–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brubaker L, Khullar V, Piault E, et al. Goal attainment scaling in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: development and pilot testing of the Self-Assessment Goal Achievement (SAGA) questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:937–946. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannion AF, Caporaso F, Pulkovski N, Sprott H. Goal attainment scaling as a measure of treatment success after physiotherapy for chronic low back pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1734–1738. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohr KN, Zebrack BJ. Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: challenges and opportunities. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18:99–107. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donaldson G. Patient-reported outcomes and the mandate of measurement. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17:1303–1313. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredericksen R, Edwards TC, Crawford P, et al. Patient and provider priorities for self-reported domains of clinical care. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1050983. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magasi S, Ryan G, Revicki D, et al. Content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: perspectives from a PROMIS meeting. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:739–746. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Tufano J, et al. Integrating a web-based patient assessent into primary care for HIV-infected adults. Journal of AIDS and HIV Research. 2012;4:47–55. doi: 10.5897/jahr11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence ST, Willig JH, Crane HM, et al. Routine, self-administered, touch-screen, computer-based suicidal ideation assessment linked to automated response team notification in an HIV primary care setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1165–1173. doi: 10.1086/651420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54 (Suppl 1):S77–S90. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45:S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler FJ. Survey Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabine TB. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology: building a bridge between disciplines: report of the Advanced Research Seminar on Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology. National Academies; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A “How To” Guide. American Statistical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harley C, Takeuchi E, Taylor S, et al. A mixed methods approach to adapting health-related quality of life measures for use in routine oncology clinical practice. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:389–403. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9983-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Geller G, Carducci MA, Wu AW. Relevant content for a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire for use in oncology clinical practice: Putting doctors and patients on the same page. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1045–1055. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenhalgh J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work, and why? Qual Life Res. 2009;18:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]