Abstract

Recovery following an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) impacts both the patient and partner, often in divergent ways. Patients may have had a cardiac arrest or cardiac arrhythmias, whereas partners may have to perform CPR and manage the ongoing challenges of heart disease therapy. Currently, support for post-ICD care focuses primarily on restoring patient functioning with few interventions available to partners who serve as primary support. This descriptive study examined and compared patterns of change for both patients and partners during the first year post-ICD implantation. For this longitudinal study, the sample included 42 of 55 (76.4 %) patient–partner dyads who participated in the ‘usual care’ group of a larger intervention RCT with patients following ICD implant for secondary prevention of cardiac arrest. Measures taken at across five time points (at hospital discharge and at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months follow up) tracked physical function (SF-12 PCS, symptoms); psychological adjustment (SF-12 MCS; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; CES-D); relationship impact (Family Functioning, DOII; Mutuality and Interpersonal Sensitivity, MIS); and healthcare utilization (ED visits, outpatient visits, hospitalizations). Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to characterize and compare outcome trends for patients and partners across the first 12 months of recovery. Patients were 66.5 ± 11.3 (mean + SD) years old, predominately Caucasian male (91 %), with Charlson co-morbidities of 4.4 ± 2.4. Partners were 62.5 ± 11.1 years old, predominantly female (91 %) with Charlson co-morbidities of 2.9 ± 3.0. Patient versus partner differences were observed in the pattern of physical health (F = 10.8, p <0.0001); patient physical health improved while partner health showed few changes. For partners compared to patients, anxiety, depression, and illness demands on family functioning tended to be higher. Patient mutuality was stable, while partner mutuality increased steadily (F = 2.5, p = 0.05). Patient sensitivity was highest at discharge and declined; partner sensitivity increased (F = 10.2, p < 0.0001) across the 12-month recovery. Outpatient visits for patients versus partners differed (F = 5.0, p = 0.008) due most likely to the number of required patient ICD visits. Total hospitalizations and ED visits were higher for patients versus partners, but not significantly. The findings highlight the potential reciprocal influences of patient and partner responses to the ICD experience on health outcomes. Warranted are new, sound and feasible strategies to counterbalance partner needs while simultaneously optimizing patient recovery outcomes.

Keywords: Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), Psychological adjustment, Recovery, Significant other, Partner relationship, Sudden cardiac arrest

Introduction

Notable advances in cardiac rhythm management and the concomitant increased use of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) have dramatically altered cardiac care in the U.S. The recovery post-ICD implantation is complex and at times prolonged, placing new demands on significant others who provide support and care. Although there are some recent findings regarding the physical and psychosocial adjustment of patients following ICD implantation (Magyar-Russell et al., 2011; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011; van den Broek et al., 2011), little is known about the impact of the cardiac illness on the overall health of partners and how this impacts patient recovery. Research indicates that the physical health and psychological well-being of the patient’s intimate partner is important in recovery after cardiac illness (Hwang et al., 2010; Pycha et al., 1990). Because intimate partners provide essential physical and psychological support to patients following ICD implantation, it is also important to understand the impact of the patient’s cardiac illness on the intimate partner’s overall health. The psychosocial distress posed by the underlying arrhythmia and its potential treatment for patients and family members can be under appreciated by health care providers (Dunbar et al., 2012). For both patients and their partners, coping and adjustment is not limited to the single event that results in the ICD implant, but to a process that unfolds with increasing knowledge of the heart condition, arrhythmia treatment and device-related events, and demands associated with return to activities of daily living and exercise.

Patient post-ICD implantation recovery is associated with a range of physical symptoms, some of which mitigate over time, including palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, sleep disturbances, loss of libido and fatigue (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011). Recovery of physical functioning from ICD implantation, particularly for those who receive an ICD for secondary prevention, occurs across 1–2 years, frequently punctuated by health setbacks and ICD shocks (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011). Psychological distress and, in contradiction, quality of life have been found to decline across the recovery period (Dunbar et al., 2012; Magyar-Russell et al., 2011; van den Broek et al., 2011). Patient psychological distress, anxiety in particular, is linked to pre-existing psychological and physical health, personality factors, number and timing of ICD shocks and shock storms (Pedersen et al., 2004; Redhead et al., 2010). Importantly for patients, social support is associated with reduced depression and anxiety, emphasizing the need to study post-ICD adjustment within the context of partner relationships (Kamphuis et al., 2004). Patient adaptation may be hindered if the partner simultaneously experiences physical or psychological problems due to his or her own health, or to stressors related to living with and caring for, an individual with a newly implanted ICD (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011; van den Broek et al., 2010).

Partner physical and psychological adjustments have been considered in only a few studies. The most challenging time to partners’ physical and psychological well-being has been shown to be in the first 3 months post-ICD (Dougherty & Thompson, 2009). Essentially, partner physical health may decline (Jenkins et al., 2007) during the first year post-ICD, with partner anxiety remaining higher than that of the ICD patient (Kapa et al., 2010; Magyar-Russell et al., 2011). Partner concerns reflect the physical and emotional demands of caring for the ICD patient, at times manifested as helplessness and overprotectiveness (Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011; van den Broek et al., 2010). It has been reported that psychological distress and family adjustment can be adversely affected in patients who received ICD shocks (Dougherty, 1995). Ocampo (2000) suggested that although the patient becomes more accepting of the device and related lifestyle changes, this adaptation might be more challenging for partners. Factors that impede partner psychological adjustment include uncertainties regarding ICD shocks, shifts in marital and family role relationships, and the resumption of typical life activities such as driving and sexual relations (van den Broek et al., 2010).

Sudden cardiac arrest can strain the intimate relationship by impacting dyadic communication patterns, requiring unanticipated role changes, and placing limitations on activities, social and otherwise (Dunbar et al., 2012). Relationship cohesion is a vital form of support affected by the psychological well-being of individuals in the relationship (Moser & Dracup, 2004; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011; Rohrbaugh et al., 2006). Doolittle & Sauve (1995) reported that patient versus partner differences in perceptions about ICD recovery created conflicts within the dyad. Spouses tended to discontinue social activities with friends and outside the family to be readily available to address patient needs. In extreme instances, spousal protectiveness led to ‘entrapment’ of the ICD patient resulting in decreased social activities for the ICD patient, altered communication between the spouse and patient, and feelings of anger and frustration toward the spouse’s restrictions. Evidence from research conducted with dyads living with heart failure shows that partner depressive symptoms are linked to patient reduced sense of social support, low relationship satisfaction, diminished confidence to manage heart failure (Trivedi et al., 2012), and patient quality of life (Chung et al., 2009). In response to both heart failure and ICD implantation, dyadic communication is disturbed for some couples while improved for others (Imes et al., 2011); improvement is associated with couple cohesiveness.

Furthermore, the relationships between partner health and healthcare utilization have been understudied, particularly for partners of ICD recipients. It is known that individuals who care for a disabled spouse risk inadequate rest, insufficient time to exercise, forgetting their prescription medications, and prolonged recuperation from illness (Burton et al., 1997). Likewise, partners caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease tend only secondarily to their own medical needs (Shaw et al., 1997).

While research has increased understanding of patient responses following serious cardiac arrhythmias and ICD implantation, little remains known about the patterns and complexities of both patient and partner responses. Recovery from serious cardiac illness occurs within the context of family relationships; understanding its impact in relationship to the partner as well as the patient will advance the knowledge of patient–partner needs and their reciprocal influences that are needed to specify targets for early intervention. This study examined the impact of ICD implantation on patients and their intimate partners over the first year following receipt of an ICD. The specific study aims were to compare levels and patterns of patient and intimate partner physical functioning, psychological adjustment, relationship impact, and healthcare utilization during the first year post-ICD implantation.

Methods

This secondary analysis examined data collected for a randomized clinical trial, which was designed to test the efficacy of a nursing intervention for patients who had received an initial implanted ICD. The goal of the original study was to examine for intervention efficacy to improve physical functioning and enhance psychological adjustment in the first year after ICD receipt (Dougherty et al., 2004). The sample in the current study included only patients randomized to usual care (no intervention) and their intimate partners. Data were collected longitudinally beginning at hospital discharge following the ICD implant, and then at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months.

Participants

In this study, all patients were recent recipients of an initial ICD for secondary prevention following sudden cardiac arrest or serious ventricular arrhythmia. Intimate partners included significant others (spouse, lover, partner) who were currently living with the patient. Inclusion criteria included patient intending to return home post-ICD implantation; English language (ability to read, write and speak); patient and partner available for phone contact; and willingness to participate in the study for one year. Exclusion criteria were age less than 21 years and/or severely impaired cognitive function due to co-morbidities (Dougherty et al., 2004). Of the 168 eligible patients who had received an ICD implant, 83 were assigned to usual care and 85 were assigned to the intervention condition. Of the 83 usual care patients, 55 (66.3 %) had an intimate partner, of which 42 (76.4 %) participated in each of the five data collections.

Procedures

Study procedures for the original study were approved by the university Institutional Review Board prior to approaching potential study participants. Patients were recruited from ten hospital study sites in the Pacific Northwest. The partner, if eligible, was approached for study participation after the patient was consented. Common reasons for declining study participation were that individuals did not want to complete questionnaires, partners had major health problems, or the patient requested that the partner not participate.

Patients interested in participating were screened based on eligibility criteria and completed a health history. Patients and partners were mailed study questionnaires along with postage-paid, return envelopes. Instructions requested that participants complete the questionnaires independently and not discuss their responses with one another. Health histories and demographics were collected by telephone at baseline. Health records were used to calculate Charlson co-morbidity scores (Charlson et al., 1987). Healthcare utilization data were also collected at each data collection period; medical records were used to verify hospitalizations.

Measures

Questionnaires were completed by patients and their partners at five time points: after hospital discharge following the initial ICD implant, and again at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months follow up. Generally, scale scores reflected higher values of the measured construct. One exception was that higher values on the family functioning measures (DOII) reflected adverse impact of illness demands, and thus lower family functioning.

Physical functioning, operationalized as general health and physical symptoms, was measured with the Short Form (SF-12) Health Survey, a 12-item version of the SF-36 (Ware et al. 1995; Ware, 1987). Physical health (PCS) and mental health (MCS) composite scores have a possible range of 0–100, with internal consistency reliabilities of 0.94–0.96 (Dougherty et al., 2005). Physical symptoms currently experienced were measured using the Physical Symptom scale (14 items) from the Demands of Illness Inventory (DOII) (Haberman et al., 1990; Woods et al., 1993). Validation of the DOII has been established with individuals and family members managing a range of chronic and serious illnesses, including cancer and diabetes. Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach alpha) coefficients range from 0.85 to 0.92 for subscales (Haberman et al., 1990).

Psychological adjustment was operationalized using established measures of mental health, depression and anxiety. Mental health was assessed with the SF-12 MCS scale from this general health measure. Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D, a 20-item scale, captures depression symptoms and has with a reliability of 0.87 (Dougherty et al., 2005). Based on normative values derived from diverse populations, a cut-off score >16 represents increased risk for clinical depression. Anxiety was measured using the state measure from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, 20 items) (Speilberger et al., 1970). Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach alpha) for an ICD sample was 0.84 (Dougherty et al., 2005). The STAI has been widely used in clinical settings and research, including with cardiovascular populations (Bloom, 1979; Rose & Devine, 2014) and, importantly, is sensitive to change across time. For the STAI, a cut-off score ≥30 indicates moderate anxiety; a score ≥40 signals clinically significant anxiety.

Relationship impact was measured along three dimensions: family functioning, mutuality and sensitivity, and by caregiver burden for partners. Family functioning was measured using two scales from the Demands of Illness Inventory (DOII), described above (Haberman et al., 1990; Woods et al., 1993). The personal meaning scale (15 items) assesses the impact of illness on the meaning of one’s life (goals, values, priorities). The family functioning scale (24 items) measures the adverse impact of the illness on functioning of the family unit. Higher scores reflect the more adverse effects of illness demands on personal meaning and family functioning.

Mutuality and sensitivity were assessed with the Mutuality and Interpersonal Sensitivity (MIS) scale (Cochrane et al., 2011). This self-report (32 items) measures shared meanings, attitudes, and orientation toward living with an ICD. The mutuality scale (16 items) captures similarity of thoughts and feelings about the ICD by members of the dyad. The interpersonal sensitivity scale (16 items) captures the extent to which partners are sensitive and attentive to the thoughts and feelings of the patient, from the perspective of both members of the dyad. Cronbach alpha reliability for the total scale is 0.93 (Cochrane et al., 2011).

Caregiver burden was measured using the Demands of Caregiving Inventory (Wallhagen, 1992), a self-report scale (23 items) that assesses partner care responsibilities associated with patient activities of daily living and other demands related to providing care. The scales measure the frequency with which patient needs and tasks are met by the partner, and the perceived difficulty in carrying out specific tasks or in meeting patient care needs. The scale has been validated with caregivers of the frail elderly, individuals with dementia, and cancer patients. Reliabilities for the scales are 0.84 and 0.83, respectively.

Healthcare utilization was based on the number of patient and partner emergency department visits, outpatient clinic visits, and hospitalizations derived from self-report data. Hospitalizations and discharge diagnoses were verified using hospital records. The intervals between data collections varied across the 12 month recovery period: at 1 month the measurement interval was 1 month (baseline to 1 month); at 3 months, the interval was 2 months (1–3 months); at 6 months the interval was 3 months (3–6 months); and at 12 months the interval was 6 months (6–12 months). To adjust for these interval differences, health care utilization was calculated as the average number of visits per month across each data collection interval.

Analysis

Patterns of response for the patient versus the partner groups over time were described using frequency and distribution statistics, plots, and Pearson product-moment correlations. Data were examined for violations of the assumptions (e.g., normality, sphericity) underlying the statistical tests. Repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) was used to characterize the patterns of change in outcomes for the patient and partners groups based on data collected the first 12 recovery months. In addition, we tested for group x time interaction effects to explore for differences between patient and partner groups, and examined for group differences in linear and quadratic trends. We used the Greenhouse-Geisser correction when appropriate if the RM ANOVA sphericity assumption was not met (Stevens, 2009). Age, sex and ethnicity were included as control variables initially, but, when found to be non-significant, were deleted due to the moderately small sample size. Significance was established at p <.05. Because we were interested in uncovering differences in patterns across time for patients and partners and the sample size was relatively small, we interpreted p values uncorrected for multiple comparisons (cf. Feise, 2002; Leon, 2004; Rothman, 1990). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (IBM, Chicago, Il, USA).

Results

ICD patients averaged 66.5 years of age, and were predominantly male and Caucasian (Table 1). Approximately 27 % were college graduates, 35 % were employed with 42 % having an annual household income >$49,999. The average Charlson co-morbidity index was 4.4, meaning that prior to ICD implant patients experienced on average more than four chronic conditions. Common were hypertension, heart failure, myocardial infarction and stroke. More than half of the sample was sedentary with an average BMI of 27.8 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patient-partner pairs

| Variables | Patients

|

Partners

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or Mean | % or SD | N or Mean | % or SD | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 44 | 80.0 | 12 | 21.8 |

| Female | 11 | 20.0 | 43 | 78.2 |

| Mean age | 66.5 | 11.3 | 62.5 | 11.1 |

| < 50 | 6 | 16.1 | 9 | 17.5 |

| 50–59 | 7 | 16.1 | 12 | 22.7 |

| 60–69 | 20 | 23.2 | 16 | 30.9 |

| 70–79 | 16 | 39.3 | 15 | 25.8 |

| > 79 | 6 | 5.4 | 2 | 3.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 50 | 90.9 | 50 | 90.9 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1.8 | – | – |

| Am Indian/Alaskan | – | – | 1 | 1.8 |

| Black/African American | 2 | 3.6 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Mixed race/ethnicity | 1 | 1.8 | – | – |

| Missing | 1 | 1.8 | 3 | 5.5 |

| Education | ||||

| Some high school | 5 | 9.1 | 4 | 7.3 |

| Graduated high school | 14 | 25.5 | 16 | 29.1 |

| Some college | 13 | 23.6 | – | – |

| 2 years college or vocational | 8 | 14.5 | 10 | 18.2 |

| Graduated college | 5 | 9.1 | 8 | 14.5 |

| Graduate | 10 | 18.2 | 4 | 7.3 |

| Missing/Other | – | – | 13 | 23.6 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time | 11 | 20.0 | 16 | 29.1 |

| Part-time | 8 | 14.5 | 3 | 5.5 |

| Not employed | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Retired | 29 | 52.7 | 24 | 43.6 |

| Full-time housewife | 2 | 3.6 | 9 | 16.4 |

| Disabled | 4 | 7.5 | – | – |

| Missing | – | – | 2 | 3.6 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| < 30,000 | 9 | 16.4 | – | – |

| 30,000–49,999 | 16 | 29.1 | – | – |

| > 49,999 | 23 | 41.7 | – | – |

| Missing | 7 | 12.7 | – | – |

| Illnesses | ||||

| Diabetes | 12 | 21.8 | 6 | 14.3 |

| COPD | 5 | 9.1 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Arthritis | 13 | 23.6 | 8 | 14.5 |

| High blood pressure | 35 | 63.6 | 17 | 41.5 |

| Claudication | 4 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CHF | 30 | 54.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Carotid disease | 2 | 3.6 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Stroke | 10 | 18.2 | 2 | 4.8 |

| Thyroid disease | 7 | 12.7 | 3 | 7.1 |

| Liver/kidney disease | 4 | 7.3 | 2 | 4.8 |

| High cholesterol | 26 | 47.3 | 10 | 18.2 |

| Valvular heart disease | 11 | 20.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 29 | 52.7 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Depression ≥ 16 | 10 | 18.2 | 12 | 28.6 |

| Anxiety ≥ 40 | 15 | 27.3 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Current smoker | 7 | 12.7 | 6 | 14.3 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 27 | 49.1 | 17 | 40.5 |

| Heart arrhythmia | 16 | 29.1 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index | 4.4 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 | 5.1 | 29.5 | 4.9 |

Intimate partners averaged 62.5 years of age, and were primary female and Caucasian. About 20 % were college graduates, 35 % were employed, primarily in clerical or managerial positions. Intimate partners reported a number of their own health concerns at the time of patient ICD implant, notably hypertension and myocardial infarction, with an average Charlson co-morbidity index of 2.9. Below, for each of the conceptual domains examined in this study, we first describe findings for patient outcomes, then partner outcomes, and then a comparison of patient versus partner outcomes across time.

Physical functioning

The general health of ICD patients, measured by the SF-12 PCS, was lowest at baseline (hospital discharge), increased thereafter [F(4,44) = 9.15, p = 0.001], remaining above baseline throughout the 12 months (Table 2). Physical symptoms, measured with the DOII, decreased significantly across time [F(4,37) = 3.01, p = .03]. Over the 12-month period, the most common symptoms reported by patients remained similar. The top five physical symptoms reported at hospital discharge were feeling run down (70.7 %), feeling weak in the body (61.3 %), soreness of muscles (60.5 %), back pain (48.8 %), and faintness (47.4 %). At 12 months, the top five symptoms were feeling run down (55.6 %), feeling weak in the body (52.8 %), inability to stay at usual weight (49.3 %), back pain (48.6 %), and soreness of muscles (47.2 %).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations and within group repeated measures statistics for patients and partners

| Variables by patient and partner | Occasion

|

Statistics

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital discharge

|

1 month

|

3 months

|

6 months

|

12 months

|

F (time) | p value | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Physical functioning | ||||||||||||

| SF-12 Physical Composite Pt | 35.02a | 9.16 | 41.25b | 10.31 | 42.63b | 11.13 | 42.66b | 11.17 | 41.00b | 12.25 | 9.15 | 0.001 |

| SF-12 Physical Composite Pr | 48.06 | 10.72 | 46.54 | 10.66 | 45.82 | 11.31 | 47.00 | 10.23 | 46.77 | 10.59 | 1.27 | 0.30 |

| Physical Symptoms (DOII) Pt | 5.66ade | 3.39 | 4.56bcde | 3.44 | 4.10bce | 3.80 | 5.12abde | 3.72 | 4.73abcde | 3.99 | 3.01 | 0.03 |

| Physical Symptoms (DOII) Pr | 2.52 | 3.05 | 2.64 | 3.25 | 2.40 | 3.27 | 1.93 | 2.65 | 1.93 | 2.87 | 0.97 | 0.44 |

| Psychological adjustment | ||||||||||||

| SF-12 Mental Composite Pt | 53.15 | 9.51 | 53.26 | 7.94 | 54.40 | 7.81 | 54.53 | 8.06 | 54.90 | 8.25 | 0.65 | 0.63 |

| SF-12 Mental Composite Pr | 48.89 | 11.06 | 50.74 | 10.89 | 51.96 | 8.84 | 52.52 | 8.91 | 51.75 | 9.73 | 1.46 | 0.23 |

| Anxiety (STAI) Pt | 31.17 | 9.81 | 30.50 | 9.65 | 30.63 | 9.66 | 30.73 | 10.88 | 29.87 | 10.20 | 0.17 | 0.95 |

| Anxiety (STAI) Pr | 36.90 | 12.36 | 34.62 | 13.64 | 33.21 | 13.31 | 33.50 | 11.78 | 34.14 | 12.02 | 1.07 | 0.39 |

| Depression (CES-D) Pt | 9.36 | 7.48 | 8.16 | 8.43 | 7.23 | 7.36 | 8.32 | 8.85 | 8.65 | 8.46 | 1.35 | 0.27 |

| Depression (CES-D) Pr | 12.34a | 10.64 | 9.55b | 9.55 | 8.27b | 9.45 | 7.93b | 9.11 | 9.12b | 9.30 | 2.18 | 0.09 |

| Relationship impact | ||||||||||||

| Personal Meaning (DOII) Pt | 10.63a | 4.58 | 10.27abce | 4.98 | 9.33bcde | 5.04 | 8.69cde | 5.45 | 9.33bcde | 5.28 | 2.06 | 0.10 |

| Personal Meaning (DOII) Pr | 8.07 | 5.21 | 8.67 | 4.61 | 8.21 | 4.78 | 7.69 | 5.18 | 7.81 | 5.14 | 1.02 | 0.41 |

| Family Function (DOII) Pt | 11.70 | 7.46 | 10.55 | 7.27 | 10.47 | 7.77 | 9.66 | 7.71 | 10.26 | 7.78 | 0.96 | 0.43 |

| Family Function (DOII) Pr | 13.49 | 7.60 | 13.15 | 7.67 | 11.63 | 7.38 | 11.10 | 8.09 | 11.24 | 7.96 | 1.68 | 0.18 |

| Mutuality (MIS) Pt | 4.38acde | 0.52 | 4.30bce | 0.47 | 4.41abcde | 0.44 | 4.43acd | 0.60 | 4.34abce | 0.65 | 2.23 | 0.08 |

| Mutuality (MIS) Pr | 4.20 | 0.45 | 4.33 | 0.56 | 4.32 | 0.53 | 4.32 | 0.59 | 4.43 | 0.53 | 2.03 | 0.11 |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity (MIS) Pt | 3.45a | 0.72 | 3.37abd | 0.63 | 3.09cde | 0.71 | 3.21bcde | 0.89 | 3.16cde | 0.79 | 9.68 | 0.001 |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity (MIS) Pr | 2.84a | 0.41 | 3.40b | 0.69 | 3.41b | 0.76 | 3.36b | 0.67 | 3.29b | 0.72 | 4.15 | 0.007 |

| Care Demands Pr (BCN) | 2.29a | 0.88 | 2.11abc | 0.80 | 2.01bcd | 0.89 | 2.01bcd | 0.75 | 1.87cd | 0.90 | 2.45 | 0.06 |

| Care Difficulty Pr (BCN) | 1.72a | 0.75 | 1.65a | 0.81 | 1.43b | 0.73 | 1.42b | 0.66 | 1.51b | 0.75 | 7.38 | 0.001 |

| Healthcare utilization (average/month) | ||||||||||||

| ED visits total Pt | – | – | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 0.73 |

| ED visits total Pr | – | – | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.009 | 0.05 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.38 |

| Total outpatient visits Pt | – | – | 1.67a | 1.01 | 0.95b | 0.48 | 0.66c | 0.59 | 0.76bc | 0.77 | 10.37 | 0.001 |

| Total outpatient visits Pr | – | – | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 1.01 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 1.85 | 0.16 |

| Total hospitalizations Pt | – | – | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.77 | 0.52 |

| Total hospitalizations Pr | – | – | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.38 |

Bold fonts designate partner outcomes. To adjust for time differences in data collection intervals, healthcare utilization was calculated as the average number of visits/month for each data collection interval. Thus, the average total number of patient outpatient visits from 3 to 6 months is calculated as .66 × 3 = 1.98 or about 2 visits between 3 and 6 months; similarly, the average total outpatient visits from 6 to 12 months is .76 × 6 = 4.56. For variables with statistically significant main effects and trends toward significance: values with the same superscript are similar, do not differ significantly. Values with different superscripts are significantly different from one another

SF-12 Short Form Health Survey, STAI State Anxiety, CES-D Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, DOII Demands of Illness Inventory, MIS Mutuality and Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale, BCN Behavioral Care Needs Inventory, ED Emergency Department, Pt patient, Pr partner

No significant changes were reported in partner physical function (SF-12 PCS) or physical symptoms (DOII) over the 12 months. Partners reported an average of 2.5 symptoms at hospital discharge and a similar average of 2 symptoms at 12 months. The most prevalent physical symptoms reported by partners at the time of patient hospital discharge were feeling run down (62.4 %), headache (35.9 %), back pain (29.9 %), nausea/vomiting (28.2 %), and muscle soreness (26.5 %). At 12 months, partners reported feeling run down (32 %), inability to stay at usual weight (28 %), muscle soreness (24 %), back pain (23 %), and headache (19 %).

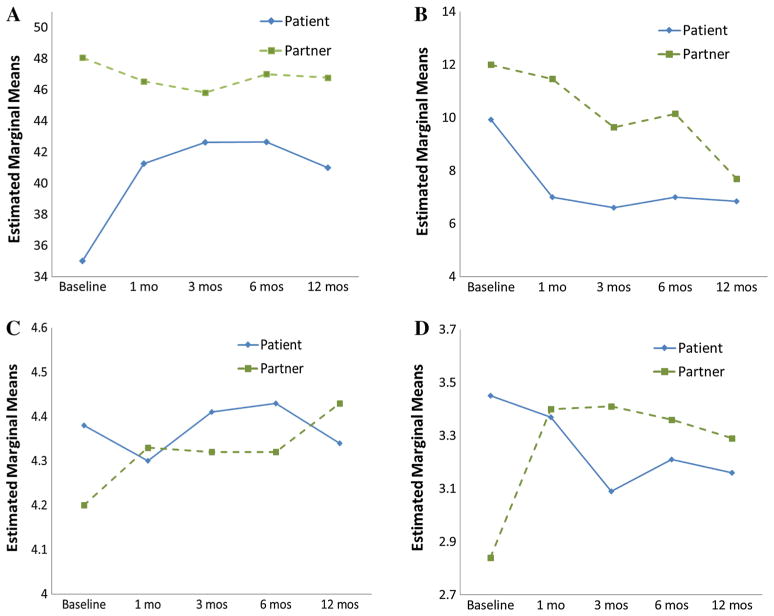

In comparison, while patients showed improvement in general physical health 1 year post-ICD, partners showed few changes in physical health across time (Table 2). At baseline the mean partner SF-12 PCS was 13 points greater than the mean patient score. At 12 months, the mean partner score was 6 points higher. As depicted in Fig. 1a and summarized in Table 3, significant differences in patients versus partners physical health were noted in both the level and pattern of change [linear trend, Flin(1,40) = 10.06, p = 0.003; quadratic trend, Fquad(1,40) = 25.57, p ≤ 0.0001]. Likewise, patient versus partner trend differences [quadratic trend, Fquad(1,33) = 5.36, p = 0.03], not shown in Fig. 1, were found for physical symptoms (DOII).

Fig. 1.

Patterns of change for patients (blue solid lines) and partners (green dashed lines) during first year post-ICD implantation. a Physical functioning: physical health (SF-12 PCS), b relationship impact: family functioning (DOII), c relationship impact: mutuality (MIS), d relationship impact: interpersonal sensitivity (MIS) (Color figure online)

Table 3.

Summary of repeated measures ANOVA for significant group effects and/or group by time interaction effects for patient-partner pairs

| Variable | F test Group |

p value | F test Time × Group interaction |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | ||||

| Physical Health (SF-12 PCS) | 10.84 | 0.002 | 10.79 | < 0.0001 |

| Physical Symptoms (DOII) | 23.57 | 0.0001 | 2.09 | 0.09 |

| Relationship impact | ||||

| Family Functioning (DOII) | 5.18 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.74 |

| Mutuality (MIS) | 3.18 | 0.08 | 2.50 | 0.05 |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity (MIS) | 0.36 | 0.55 | 10.15 | < 0.0001 |

| Healthcare utilization | ||||

| Outpatient Visits | 94.63 | 0.0001 | 4.98 | 0.008 |

| Hospitalizations | 3.77 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.84 |

Group = patient group versus partner group

SF12 Short Form Health Survey, DOII Demands of Illness Inventory, MIS Mutuality and Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale

Psychological adjustment

Patient mental health status, anxiety, and depression (measured with the SF-12 MCS, STAI, and CES-D, respectively) did not change significantly over time (Table 2). At baseline, the mean patient STAI score was 31.2, declining minimally to an average of 30 at 12 months. STAI scores ≥ 40 represent clinically significant anxiety; the average patient scores were below this cut point throughout the year. At baseline, the mean CES-D score for patients was 9.36, then lowest at 3 months with slight increases at 6 and 12 months, reflecting an overall minimal decrease in depression symptoms over the initial year post-ICD. Across all time points, the average scores remained ≤16, the cut point used to identify significant depression. However, at baseline, 27 % of the patients had anxiety scores elevated ≥40 and 18 % had depression scores ≥16.

Regarding partner psychological adjustment, during the recovery period, no statistically significant changes were observed for mental health, state anxiety or depression (measured with the SF-12 MCS, STAI, and CES-D, respectively). Partner mental health (SF-12 MCS), was lowest at the time of hospital discharge, showing slight improvements across time (Table 2). There were no significant changes in mean STAI scores, with partner anxiety remaining moderately high (>30) across the 12-month period. Depressive symptoms were highest at baseline, declined during the first 6 months, with modest increase during the final 6 months. Across all time points, the average partner depression scores remained ≤16. Notably, however, at baseline, 48 % of the partners had anxiety scores elevated ≥40 and 29 % of the partners had depression scores ≥16.

In comparison, anxiety in patient and partner groups decreased slightly over time, with no significant differences in trends across time (Table 2). Partners compared to patients reported significantly higher anxiety (t = 2.14, p = .04) at baseline. There were also no significant trend differences in depression across time, although partners tended to report more depression (t = 1.73, p = .08) at baseline, with higher values at each time point across time except at 6 months.

Relationship impact

For patients, the demands of illness on personal meaning and family functioning decreased from hospitalization to 12 months (Table 2), though not significantly. At baseline, the most commonly identified demands on the family were: the need for the partner to take on more household responsibility (76.8 %); having less energy and time for recreational activity (60.7 %); patient needing to protect the partner from stress (57.1 %); changes in the quality of sex activity (55.4 %); having to decide what was important for the family (53.6 %); and having less time for friends (53.6 %). At 12 months, many of the same family illness demands remained foremost: partner needed to take on more household responsibility (42.9 %); patient need to protect partner from stress (46.8 %), to be more sensitive to partner’s needs (42.9 %), to provide more support (44.6 %); changes in the frequency (51.8 %) and quality (51.8 %) of sex; and the need to change meal patterns (48.2 %). For patients, relationship mutuality showed slight fluctuations during the first 12 months, while interpersonal sensitivity declined significantly [F(4,38) = 9.68, p = 0.001] across time (Table 2).

For partners, the impact of illness demands on personal meaning and family functioning declined across time, although the overall trend was not statistically significant. The most commonly identified illness demands on family functioning at hospital discharge were having to protect the patient from stress (68.6 %); having to make changes in meal patterns (60.8 %); worrying about the patient’s response to illness (58.8 %); helping patient with treatments (58.8 %); not having enough time or energy for friends (56.9 %) or to entertain friends at home (56.9 %); and needing to be more sensitive to patient’s moods (54.9 %). At 12 months, the most common family illness demands were similar to those at baseline: having to make changes in meal patterns (54.9 %); having to protect the patient from stress (49 %); worrying about the patient’s response to illness (49 %); patient having to change job (45 %); deciding what is important for the family (45 %); and not having enough time or energy for recreational activities (45 %). For partners, interpersonal sensitivity improved significantly [F (4,37) = 4.15, p = 0.007] across time (Table 2). Correspondingly, behavioral care demands and difficulty experienced by the partner decreased between baseline and 12 months [F (4,36) = 7.38, p = 0.001].

Comparisons of the impact of the ICD implantation on patients versus partners revealed no trend differences in illness demands on family function (Table 3; Fig. 1b), with both patient and partner groups reporting reductions across time. Partners compared to patients reported modest differences in demands at each time point, with the greatest difference evident at 1 month post-ICD. At 12 months, patient and partner groups reported similar levels of illness demands on family functioning.

Patients versus partners showed significant differences in trends of mutuality and interpersonal sensitivity (Table 3). Compared to partners, patient mutuality (Fig. 1c) was higher at hospital discharge, decreased at 1 month, rose steadily at 3 and 6 months, and dropped below baseline at 12 months [Fcubic(1,39) = 7.72, p = 0.008]. Conversely, partner mutuality increased modestly across time. Patterns of interpersonal sensitivity (Fig. 1d) for patient versus partner groups also differed markedly across time [Fquad (3.1,37) = 10.15, p < 0.0001]. Patient interpersonal sensitivity was highest at hospital discharge and declined with time, whereas partner sensitivity was initially lower, increased at 1 month and remained relatively stable through 12 months. The most notable changes were reflected in differences in linear trends [Flin(1,37) = 15.5, p <0.0001] and quadratic trends [Fquad (1,37) = 13.5, p = 0.001] during the first 3 months.

Healthcare utilization

No significant changes were observed in the monthly average number of patient emergency department (ED) visits or hospitalizations during first year post-ICD implantation (Table 2). Typically, there was ≤1 ED visit per patient per month, and 17 patients (30.9 %) experienced at least one (and up to three) hospitalizations during the first year. The monthly average number of outpatient visits decreased significantly [F (3, 36) = 10.37, p = 0.001] between ICD implant and the 12-month follow-up, with most visits occurring during the first 3 months post-ICD implantation. For patients, the average number of total outpatient visits was 5.6 during the first 6 months of the year and 4.6 visits during the second 6 months.

For partners, there were no significant changes in the average monthly number of emergency department, hospitalizations, or monthly outpatient visits (Table 2). Partners had an average of 2 outpatient visits during the first 6 months and 1.3 visits during the second 6 months.

Healthcare accessed through emergency departments was consistently low for patients and partners, with each group averaging less than one visit per month (Table 2). Trends in patient and partner outpatient visits differed significantly (F = 4.98, p < 0.008) due to fewer partner outpatient visits in contrast to a higher and decreasing pattern of patient outpatient visits throughout the year (Table 3). The total number of hospitalizations was higher for patients versus partners, but the overall pattern of change did not differ between groups.

Discussion

This study provided a prospective description of physical functioning, psychological adjustment, relationship impact, and healthcare utilization in patients and their partners during the first year post-ICD implantation. Patient physical functioning improved significantly with general health improving and physical symptoms decreasing across the recovery period. In contrast, partner physical functioning was relatively stable, with general health declining slightly during the same period. Partners compared to patients, reported higher levels of anxiety and depression during the first year. Of interest, patient and partners initial report of relationship quality differed significantly immediately after ICD implantation, but converged at 1 year. Patient outpatient visits declined significantly across the year. Partner healthcare utilization remained relatively low despite reported symptoms and mental health concerns.

Physical functioning

The greatest gains in patient physical functioning occurred within the first 3–6 months, a time when most patients adapt to the ICD and tolerable activity. Although patients and partners report increased preoccupation with their heart health during the first year post-ICD implant, the ICD itself is perceived positively as a ‘life extender’ (Pycha et al., 1990; Tagney et al., 2003). Our results regarding improved patient physical function and slight reductions in partner physical function are consistent with the partner study conducted with AVID trial data, where partner physical functioning appeared to decline across the year (Jenkins et al., 2007). Partners of cardiac patients tend to associate declines in their own health to stress, sleep disturbances, fatigue and loss of appetite (Blair et al., 2014; Dickerson et al., 2000; Kettunen et al., 1999; O’Farrell et al., 2000). These symptoms are consonant with patterns reported by intimate partners in this research, including feeling run down, experiencing headaches, and being unable to maintain usual weight. Partner stress has been attributed to the daily demands of caregiving, fear of the patient dying, and less time to attend to one’s own health and concerns (Blair et al., 2014; Jenkins et al., 2007).

Psychological adjustment

Partners compared to patients reported more depression and anxiety, and lower mental health functioning. Although anxiety improved across time for partners, they reported higher levels than patients at each time point, consonant with some recent observations (Kapa et al., 2010; Magyar-Russell et al., 2011; Pedersen et al., 2009; van den Broek et al., 2010).

Heightened psychological distress in partners has significant and potentially deleterious consequences for patient recovery. For instance, Moser and Dracup (2004) identified that patient adaption to illness was hindered when spousal anxiety and depression were higher than that of the patient. Psychological distress is due in part to partners assuming more responsibilities and undertaking additional everyday activities such as driving, shopping, working and childcare, thereby increasing partner stress in addition to inadvertently accentuating the patient’s real or perceived loss of independence and self-confidence (Deaton et al., 2003; Tagney et al., 2003).

Relationship impact

Over the first year, partners reported decreases in the number and difficulty of caregiving demands suggesting that patients gained independence, assumed responsibility for their own care and resumed their family roles. Both groups reported declines in the demands on family functioning, although partners tended to report more demands than did patients. Patients showed some reductions in the effects of illness demands on personal meaning across the year. Partners reported fewer illness demands on personal meaning than did patients, with little change over the ensuing year. Researchers report that after a cardiac arrest, patients come to appreciate smaller, simpler joys in life, linked either to recognition of their mortality or to reassessment of some life aspects (Bolse et al., 2005; Kamphuis et al., 2004), which may offset the impact of illness demands on emerging personal values and goals.

Patients compared to partners initially reported higher levels of relationship mutuality, the extent to which members of the dyad think similarly about ICD recovery. This converged to similar levels at 12 months. Interpersonal sensitivity, or the extent to which the couple is sensitive and attend to each others’ needs, declined across time for patients, who saw their partners as being less attentive to their needs across time. Conversely, within the first month, partners interpreted their roles as becoming more sensitive to patient needs. Declines in dyadic adjustment over the first year of ICD recovery have been described by Dougherty and Thompson (2009), who found that the greatest changes in the patient–partner relationship occurred in the first 3 months post-ICD implantation, while Kamphuis et al. (2004) reported changes occurring throughout the first year. Correspondingly, in this study patient–partner perceptions about the relationship diverged most during the first 3 months, but converged across time. Although patient–partner adjustments typically show adaptation by 1 year (Kamphuis et al., 2004; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2011) as we found, the 1-year period may not be sufficient to capture more profound changes in the patient–partner relationship.

Healthcare utilization

For both partner and patient groups, healthcare utilization was generally low despite reported physical symptoms, anxiety, depression, and caregiving demands. As anticipated, patients accessed outpatient and hospital services more frequently than partners, because patients are typically scheduled for 3–4 planned outpatient visits in the first year (Epstein et al., 2013). Partners on the other hand, had relatively low rates of healthcare utilization, which is particularly relevant because this group had ongoing medical problems as well as symptoms of emotional distress.

This study is has a number of strengths. This is one of the first longitudinal investigations to report on multiple indicators across four conceptual domains (physical function, psychological adjustment, relationship impact, and health care use), over multiple time points, using identical or comparable measures for both members of the patient–partner dyad. Although a few studies have compared changes for patients and partners post-ICD, none has explicitly studied patients who received ICDs for secondary prevention and their intimate partner on a broad range of health measures over a 1 year period. Of importance is that partners of secondary prevention patients may have traumatic memories of witnessing a cardiac arrest, coordinating emergency care, and the hospitalization experience in addition to ongoing worries regarding the patient’s return to previous level of function and recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias (van den Broek et al., 2010). Understanding how individuals in the dyad change with respect to their health, family roles and healthcare use provides greater understanding of the course of transition, thereby uncovering potential goals and targets for intervention.

Limitations

Judicious interpretation of the study findings are warranted in light of study limitations. The study findings are most applicable to patients who receive an ICD for secondary prevention and their partners, because these patient and partner responses are likely to differ from those who have not suffered cardiac arrest or cardiac arrhythmias. Although study participants were asked to complete the mailed questionnaires independently of one another, we had no control over this aspect of the reporting process and could not assess influences patients and partners might have had on one another’s responses. The sample size was relatively small, including data from patient–partner dyads in the usual care group who contributed data at all five time points, which limited the statistical power to detect small and sometimes moderate differences across time. Given the relatively small sample size and the exploratory nature of this observational research, statistical tests were not adjusted for multiple tests, heightening the likelihood of finding effects due only to chance (Feise, 2002; Leon, 2004; Rothman, 1990). In addition, data interpretation must take into consideration that the partner sample was primarily female, and that women compared to men are generally known to report higher levels of psychosocial distress. Inclusion of gender in the repeated measures ANOVA, however, revealed no effect on study outcomes.

Conclusions

The first year recovery period for patients and partners after an ICD is complex, characterized by interrelated physical, psychological and relationship changes. Our findings revealed some important differences in response patterns of patients and partners. Addressing long-term support needs and developing effective management strategies throughout the first year post-ICD could be used to promote recovery processes and health outcomes for patients and their partners. This would include intervention approaches to address improving partner symptoms and psychological adjustment, while building a repertoire of strategies to manage patient caregiving demands. Ideally, interventions specific to patient and partner anticipated needs could be initiated prior to hospital discharge coupled with longer-term follow-up to reach a broad range of patients and their partners.

Acknowledgments

Funding source National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Nursing Research, RO1 NR04766.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Cynthia M. Dougherty, Allison M. Fairbanks, Linda H. Eaton, Megan L. Morrison, Mi Sun Kim and Elaine A. Thompson declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Human and animal rights and Informed consent All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and partners prior to being included in the study.

References

- Blair J, Volpe M, Aggarwal B. Challenges, needs, and experiences of recently hospitalized cardiac patients and their informal caregivers. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2014;29:29–37. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182784123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom L. Psychology and cardiology: Collaboration in coronary treatment and prevention. Professional Psychology. 1979;10:485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Bolse K, Hamilton G, Flanagan J, Caroll DL, Fridlund B. Ways of experiencing the life situation among United States patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: A qualitative study. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;20:4–10. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2005.03797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26:162–169. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung ML, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Rayens MK. The effects of depressive symptoms and anxiety on quality of life in patients with heart failure and their spouses: Testing dyadic dynamics using Actor–Partner Interdependence Model. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane BB, Lewis FM, Griffith KA. Exploring a diffusion of benefit: Does a woman with breast cancer derive benefit from an intervention delivered to her partner? Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38:207–214. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton C, Dunbar SB, Moloney M, Sears SF, Ujhelyi MR. Patient experiences with atrial fibrillation and treatment with implantable atrial defibrillation therapy. Heart and Lung. 2003;32:291–299. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(03)00074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Posluszny M, Kennedy MC. Help seeking in a support group for recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and their support persons. Heart and Lung. 2000;29:87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle ND, Sauve MJ. Impact of aborted sudden cardiac death on patients and their spouses: The phenomenon of different reference points. American Journal of Critical Care. 1995;4:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty CM. Psychological reactions and family adjustment in shock versus no shock groups after implantation of the internal cardioverter defibrillator. Heart and Lung. 1995;24:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty CM, Lewis FM, Thompson EA, Baer JD, Kim W. Short term efficacy of a telephone intervention after an ICD. PACE: Pacing Clinical Electrophysiology. 2004;27:1594–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty CM, Thompson EA. Intimate partner physical and mental health after sudden cardiac arrest and receipt of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Research in Nursing and Health. 2009;32:432–442. doi: 10.1002/nur.20330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty CM, Thompson EA, Lewis FM. Long term outcomes of a nursing intervention after an ICD. PACE: Pacing Clinical Electrophysiology. 2005;28:1157–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.09500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar SB, Dougherty CM, Sears SF, Carroll DL, Goldstein NE, Mark DB, Zeigler VL. Educational and psychological interventions to improve outcomes for recipients of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and their families: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:2146–2172. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31825d59fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Sweeney MO. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2013;127:e283–e352. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276ce9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2002;17:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberman MR, Woods NF, Packard NJ. Demands of chronic illness: Reliability and validity assessment of a demands-of-illness inventory. Holistic Nursing Practice. 1990;5:25–35. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199010000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang B, Luttik ML, Dracup K, Jaarsma T. Family caregiving for patients with heart failure: Types of care provided and gender differences. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2010;16:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imes CC, Dougherty CM, Pyper G, Sullivan MD. Descriptive study of partners’ experiences of living with severe heart failure. Heart and Lung. 2011;40:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins LS, Powell JL, Schron EB, McBurnie MA, Bosworth-Farrell S, Moore R, Investigators AVID. Partner quality of life in the antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators trial. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22:472–479. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000297378.98754.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis HC, Verhoeven NW, Leeuw R, Derksen R, Hauer RN, Winnubst JA. ICD: A qualitative study of patient experience the first year after implantation. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13:1008–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapa S, Rotondi-Trevisan D, Mariano Z, Aves T, Irvine J, Dorian P, Hayes DL. Psychopathology in patients with ICDs over time: Results of a prospective study. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2010;33:198–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen S, Solovieva S, Laamanen R, Santavirta N. Myocardial infarction, spouses’ reactions and their need of support. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30:479–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC. Multiplicity adjusted sample size requirements: A strategy to maintain power with Bonferonni adjustments. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1511–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magyar-Russell G, Thombs BD, Cai JX, Baveja T, Kuhl EA, Singh PP, Ziegelstein RC. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in adults with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2011;71:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser DK, Dracup K. Role of spousal anxiety and depression in patients’ psychosocial recovery after a cardiac event. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:527–532. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000130493.80576.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo CM. Living with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Impact on the patients, family, and society. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2000;35:1019–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell P, Murray J, Hotz SB. Psychologic distress among spouses of patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. Heart and Lung. 2000;29:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Ceña D, Losa-Iglesias ME, Alvarez-López C, Cachón-Pérez M, Reyes RA, Salvadores-Fuentes P, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C. Patients, intimate partners and family experiences of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: Qualitative systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67:2537–2550. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SS, Spinder H, Erdman RA, Denollet J. Poor perceived social support in implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) patients and their partners: Cross-validation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:461–467. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SS, van Domburg RT, Theuns DA, Jordaens L, Erdman RA. Type D personality is associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and their partners. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:714–719. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000132874.52202.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pycha C, Calabrese JR, Gulledge AD, Maloney JD. Patient and spouse acceptance and adaptation to implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 1990;57:441–444. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.57.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report of depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Redhead AP, Turkington D, Rao S, Tynan MM, Bourke JP. Psychopathology in postinfarction patients implanted with cardioverter-defibrillators for secondary prevention. A cross-sectional, case-controlled study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC. Effect of marital quality on eight-year survival of patients with heart failure. American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;98:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M, Devine J. Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety. Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience. 2014;16:197–211. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/mrose. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Ho S, Irwin MR, Hauger RL, Grant I. Longitudinal analysis of multiple indicators of health decline among spousal caregivers. Annals of Behavavioral Medicine. 1997;19:101–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02883326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speilberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JP. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. 5. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tagney J, James JE, Albarran JW. Exploring the patient’s experiences of learning to live with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) from one UK centre: A qualitative study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;2:195–203. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi RB, Piette J, Fihn SD, Edelman D. Examining the interrelatedness of patient and spousal stress in heart failure: Conceptual model and pilot data. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2012;27:24–32. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182129ce7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek KC, Habibović M, Pedersen SS. Emotional distress in partners of patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2010;33(12):1442–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek KC, Versteeg H, Erdman RA, Pedersen SS. The distressed (Type D) personality in both patients and partners enhances the risk of emotional distress in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhagen M. Caregiving demands: Their difficulty and effects on the well-being of elderly caregivers. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice. 1992;6:111–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE. Standards for validating health measures: Definition and content. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:473–480. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Woods NF, Haberman MR, Packard NJ. Demands of illness and individual, dyadic, and family adaptation in chronic illness. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15:10–25. doi: 10.1177/019394599301500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]