Abstract

Purpose

Positive adult connection has been linked with protective effects among U.S. adolescents. Less is known about the impact of adult connection across multiple health domains for youth in low-resource urban environments. We examined the associations between adult connection and school performance, substance use, and violence exposure among youth in low resource neighborhoods.

Methods

We recruited a population-based random sample of 283 male adolescents in Philadelphia. Age-adjusted logistic regression tested whether positive adult connection promoted school performance and protected against substance use and violence exposure.

Results

Youth with a positive adult connection had significantly higher odds of good school performance (OR=2.8;p<0.05), and lower odds of alcohol use (OR=0.4;p<0.05), violence involvement (ORs=0.3–0.4;p<0.05), and violence witnessing (OR=0.3;p<0.05).

Conclusions

Promoting adult connection may help safeguard youth in urban contexts. Youth-serving professionals should consider assessing adult connection as part of a strengths-based approach to health promotion for youth in low-resource neighborhoods.

Keywords: adolescent, urban health, health promotion, schools, violence, family relations, positive youth development

Adult connection is central to positive youth development(1) and demonstrates protective effects on health and behavior outcomes among the general population of U.S. adolescents.(2–4) Research examining the simultaneous impact of positive adult connection on multiple health domains among male youth in low-resource urban environments is limited (5, 6) and warrants further investigation. Social determinants of health, including high levels of community violence and a lack of resources and opportunities, plague many urban neighborhoods. Identifying mechanisms that allow youth to thrive despite adversity is critical to promoting adolescent wellbeing. Adult connection may play a critical role in protecting youth and promoting positive youth development in these contexts, and thereby improve population health. This study examines the associations between positive adult connection and school performance, substance use and violence exposure among male youth in an urban environment.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 283 males, ages 10–24 years, enrolled via household random digit dialing in Philadelphia to recruit a representative, population-based sample from low-resource neighborhoods.(7) Based on standard formulae (8), the response rate (52.8%) was comparable to representative, random-sample surveys conducted concurrently; was high enough to suggest enrollment of a reasonably representative sample of Philadelphia youth(9, 10); and characteristics of the respondents were very similar to respondents of a separate large survey of young males in Philadelphia.(7) Participants completed in-person structured interviews during 2007–2011. Study personnel obtained written consent for older participants and assent with parental permission for minor-aged participants. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at The University of Pennsylvania and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Measures

To succinctly capture youth’s perceptions about the presence of an adult who provides support, adult connection was defined as answering affirmatively to both: “There are adults in my life that I look up to” and “that I can go to that help me handle tough situations.” These items were used to broadly measure connections both within the family and with other adults, in keeping with research demonstrating the importance of both relationships categories to adolescent outcomes.(2, 11) The structured interview included questions about school, substance use, violence involvement, witnessing violence (Things I Have Seen and Heard Scale), and neighborhood disadvantage (Neighborhood Environment Scale).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean, median, range and standard deviation for continuous variables and proportions for binary variables. We dichotomized violence witnessing and neighborhood disadvantage summary scores at natural breakpoints to reflect low and high exposure levels. Missing data (range 0–6%) was managed with multiple imputation. We used logistic regression to estimate associations between positive adult connection and school performance, substance use, and violence involvement and witnessing. Age was a significant confounder therefore included for adjustment. The analyses used STATAv12.0 (College Station, Texas).

Results

Mean participant age was 18 years old; 98% were African American and 86% reported positive adult connection. Median Neighborhood Environment Scale score (11.0) indicated high levels of neighborhood disadvantage. Prevalence of several other risk and protective factors reflected challenges experienced in low-resource environments (Table).

Table.

Characteristics of 283 adolescent male participants

| Demographics | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 17.8 (3.5) |

| Race | |

| African American | 98.0% |

| Caucasian | 1.1% |

| Native American | 0.4% |

| School/activities | |

| Currently enrolled in school | |

| <18 years old (n=118) | 99.1% |

| ≥18 years old | 44.3% |

| Ever suspended or expelled | 68.9% |

| Involved in clubs or sports | 71.8% |

| Neighborhood characteristics | Median (IQR) |

| Percent African American1 | 95.2% (55.8–98.0) |

| Percent adults with at least some college education1 | 18.8% (14.7–23.4) |

| Percent unemployed1,2 | 7.5% (5.6–10.7) |

| Median household income1 | $25,192 (20,663–30,174) |

| Median vacant properties per square mile3 | 425.5 (184.8–788.1) |

| Median Neighborhood Environment Scale (range 0–18) | 11.0 (7.0–13.0) |

| Prevalence of adult connection | % |

| Positive adult connection | 86.2% |

Measured at census tract based on participant home address from 2010 Census data

Defined based on ages 16 and greater

Obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Cartographic Modeling lab 2010 neighborhood information system database

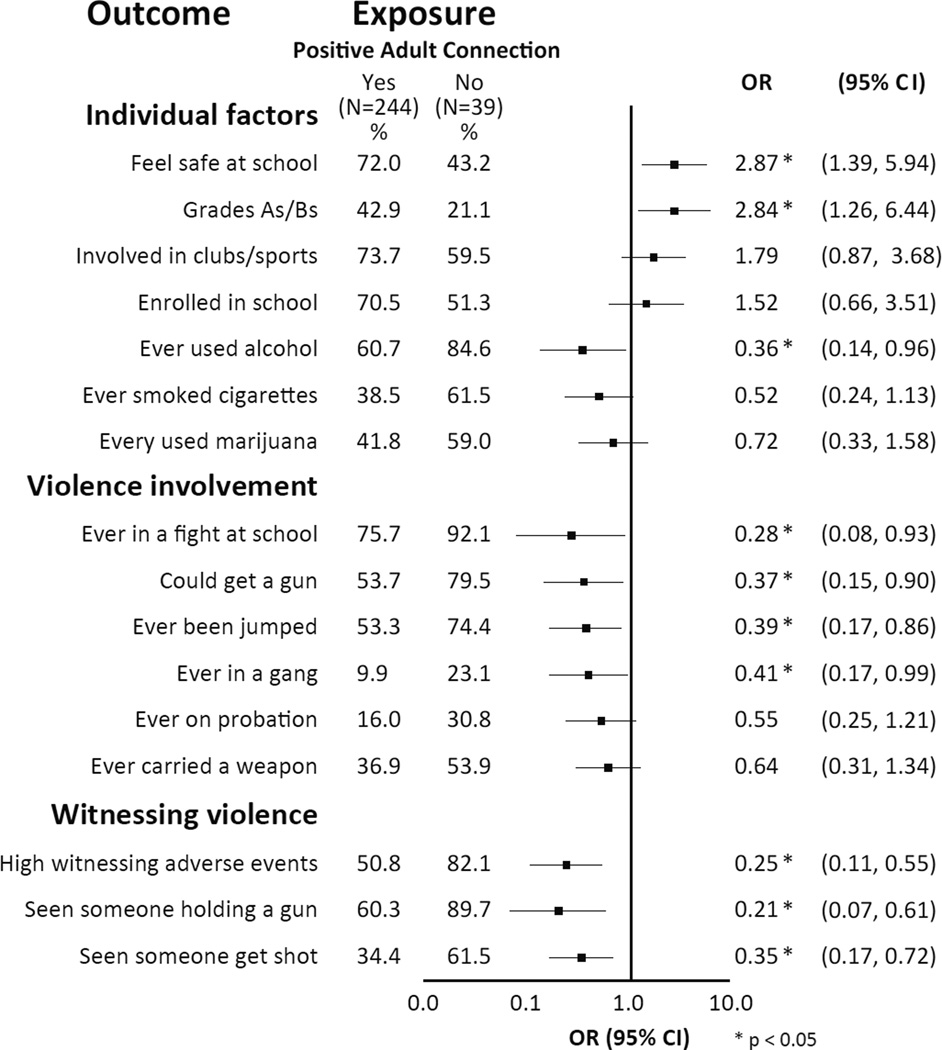

Youth with positive adult connection were more likely to report good school performance, having 2.8 times the odds of getting good grades and 2.9 times the odds of feeling safe at school (p<0.05) (Figure). Associations between adult connection and school enrollment and extracurricular activities did not reach statistical significance. Youth with positive adult connection also demonstrated a lower likelihood of ever using alcohol (OR=0.4, p<0.05). Odds ratios for tobacco and marijuana use did not reach statistical significance.

Figure.

Prevalence and adjusted odds ratios of school connection, substance use, violence involvement, and witnessing violence based on whether youth have a positive adult connection.

Furthermore, positive adult connection appeared protective against violence involvement and witnessing violence. Youth with an adult connection were less likely to be in a fight at school (OR=0.3, p<0.05), be “jumped” (OR=0.4, p<0.05), be in a gang (OR=0.4, p<0.05), and to have access to a gun (OR=0.37, p<0.05). No significant relationships were found for weapon-carrying or probation. Based on the Seen-Heard scale (mean 6.6, SD 2.8), youth reporting a positive adult connection were less likely to witness high levels of violence (OR=0.3, p<0.05), including seeing someone holding a gun (OR=0.2, p<0.05) and seeing someone get shot (OR 0.4, p<0.05).

Discussion

In a representative, population-based sample of predominantly African American male youth living in an urban environment, positive adult connection was common and was significantly associated with favorable outcomes across multiple domains including school, substance use, and violence exposure. In asking youth broadly and succinctly about relationships both within the family and with other adults, we found levels of adult support similar to those seen in samples of the general population (11, 12) and demonstrated the importance of these relationships in promoting positive outcomes.

This study, which we believe is the first to simultaneously examine specific associations of positive adult connection across multiple domains in urban environments, indicates a critical role for adults in safeguarding youth and adds violence to the list of behaviors for which adult connection offers protection. Even in the context of high levels of neighborhood disadvantage, positive adult connection appears to offer protection across critically important domains of adolescent health and wellbeing. Enhancing and promoting positive adult connections could improve population health in communities with high levels of violence exposure.

Limitations include potential for non-response bias in telephone-based recruitment, cross-sectional data that prevent concluding causation, and a solely urban focus. Broad measures of adolescent-adult relationships preclude examination of the nature of relationships, and are unable to account for potential detrimental impacts from connections with adults who promote anti-social norms. However, our findings are consistent with and additive to prior literature, and serve to highlight the importance of adult connection in promoting positive outcomes in young males in these contexts.(13, 14)

Further prospective research should examine specific mechanisms and explore which relationships are particularly impactful. Qualitative research may elucidate salient aspects of adolescent-adult relationships, identify moderating effects of adult anti-social norms, and inform evidence-based interventions to bolster adult connection and promote pro-social development (15) among male youth in low-resource environments. Although many societal-level factors need to be addressed to affect positive youth development in urban environments, families and communities can foster individual connections that have a direct impact on protecting youth.

Implications and Contribution.

This study demonstrates protective associations of positive adolescent-adult connections on school performance, substance use and violence exposure among male youth in urban environments. Promoting positive connections may help youth in low-resource urban settings thrive despite adversity. Further research should identify salient relationship characteristics to inform interventions to strengthen adult connections.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the youth who participated in the study and shared their experiences. The authors thank Matthew Culyba, MD PhD for his technical assistance with creating the article figure.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant T32HD043021-10 (grant recipient, Dr. Culyba) and grant K02AA017974 (principal investigator, Dr. Wiebe) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and grant R01AA014944 (principal investigator, Dr. Wiebe) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no potential, perceived, or real conflicts of interest to disclose. The study sponsors had no role in the (1) design and conduct of the study; (2) collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; (3) preparation, writing, review, or approval of the manuscript; and (4) decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Previous Presentations: This work was previously presented as a poster presentation at the Pediatric Academic Society Meeting, May, 2014; Vancouver, British Columbia, CA.

Contributor Information

Alison J. Culyba, Email: culyba@email.chop.edu.

Kenneth R. Ginsburg, Email: ginsburg@email.chop.edu.

Joel A. Fein, Email: fein@email.chop.edu.

Charles C. Branas, Email: cbranas@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Therese S. Richmond, Email: terryr@nursing.upenn.edu.

Douglas J. Wiebe, Email: dwiebe@exchange.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A, et al. Individual and contextual bases of thriving in adolescence: a view of the issues. J Adolesc. 2011;34:1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youngblade LM, Theokas C, Schulenberg J, et al. Risk and promotive factors in families, schools, and communities: a contextual model of positive youth development in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S47–S53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379:1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA, Bauermeister JA. A Longitudinal Analysis of Cumulative Risks, Cumulative Promotive Factors, and Adolescent Violent Behavior. J Res Adolesc. 2012;22:542–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li ST, Nussbaum KM, Richards MH. Risk and protective factors for urban African- American youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiebe DJRT, Guo W, Allison PD, Hollander JE, Nance ML, Branas CC. Mapping activity patterns to quantify risk of violent assault in urban environments. Epidemiology. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000395. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daves R. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4th Edition. Lenexa, KS: The American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2006. 'edition'. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baruch Y, Holtom BC. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations. 2008;61:1139–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groves R. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:759–779. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DuBois DL, Silverthorn N. Natural mentoring relationships and adolescent health: evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:518–524. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.031476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shahar G. Weapon violence in adolescence: parent and school connectedness as protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvert WJ. Protective factors within the family, and their role in fostering resiliency in African American adolescents. J Cult Divers. 1997;4:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: the protective effects of family functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:439–449. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale DR, Fitzgerald-Yau N, Viner RM. A systematic review of effective interventions for reducing multiple health risk behaviors in adolescence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]