Abstract

According to hedonic approaches to psychological health, healthy individuals should pursue pleasant and avoid unpleasant emotions. According to instrumental approaches, however, healthy individuals should pursue useful and avoid harmful emotions, whether pleasant or unpleasant. We sought to reconcile these approaches by distinguishing between preferences for emotions that are aggregated across contexts and preferences for emotions within specific contexts. Across five days, we assessed daily confrontational and collaborative demands and daily preferences for anger and happiness. Somewhat consistent with hedonic approaches, when averaging across contexts, psychologically healthier individuals wanted to feel less anger, but not more happiness. Somewhat consistent with instrumental approaches, when examined within contexts, psychologically healthier individuals wanted to feel angrier in more confrontational contexts, and some wanted to feel happier in more collaborative contexts. Thus, although healthier individuals are motivated to avoid unpleasant emotions over time, they are more motivated to experience them when they are potentially useful.

Keywords: Psychological health, Depression, Emotional flexibility, Emotion regulation

People can control their emotional experiences by regulating them. To regulate emotions, however, people must decide which emotions to strive for. Emotional preferences refer to emotions that people are motivated to experience (e.g., Tamir, 2009), and therefore, they determine the direction of emotion regulation (Mauss & Tamir, 2014; Tamir & Ford, 2012a). In this investigation, we ask which emotions people should strive for in their daily life to be psychologically healthy.

Individual differences in emotional preferences

Emotional preferences are often associated with emotional experiences, yet the two are conceptually and empirically distinct (e.g., Tamir & Ford, 2012a; Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, 2006). Emotional experiences reflect current states, whereas emotional preferences reflect desired end-states. By influencing emotion regulation, emotional preferences can shape emotional experiences as well as subsequent behaviour. For instance, changing the desirability of emotions, such as anxiety or anger, motivated people to experience these emotions, leading them to increase the experience of these emotions (Tamir, Bigman, Rhodes, Salerno, & Schreier, 2014). People who were motivated to increase anger increased their anger and subsequently made fewer concessions in a negotiation (Tamir & Ford, 2012a) or took more risks in a gambling task (Tamir et al., 2014).

People differ in their emotional preferences (e.g., Tamir & Ford, 2012b; Tsai et al., 2006; Wood, Heimpel, Manwell, & Whittington, 2009). Research has focused on linking individual differences in emotional preferences to stable personality (e.g., Wood et al., 2009) or cultural differences (e.g., Tsai et al., 2006). However, people may also differ in the manner in which their emotional preferences change cross contexts. Because emotional preferences influence emotion regulation and behaviour, it is important to understand how people differ in their emotional preferences across contexts, and whether such differences are related to adaptive or maladaptive psychological outcomes. This, therefore, was the goal of this investigation.

Psychological health and emotional preferences

According to hedonic approaches to well-being, psychological health is predicated on the existence of pleasure and the absence of pain (Kahneman, 1999). Emotions, from this perspective, are sources of pleasure and pain. For example, happiness is pleasant and anger is unpleasant. Psychological health, therefore, should involve less unpleasant and more pleasant emotional experiences (e.g., Diener, Sandvik, & Pavot, 1991).

If psychological health is predicated on the experience of less unpleasant and more pleasant emotions, healthier individuals should avoid unpleasant emotions and strive for pleasant emotions more than individuals who are less healthy. Some evidence is consistent with this idea. Individuals higher (vs. lower) in extraversion, who tend to be psychologically healthier, prefer pleasant emotions more and unpleasant emotions less (e.g., Kampfe & Mitte, 2009; Rusting & Larsen, 1995). In contrast, individuals higher (vs. lower) in neuroticism, who tend to be less psychologically healthy, have weaker preferences for pleasant emotions and stronger preferences for unpleasant emotions (e.g., Ford & Tamir, 2014; Kampfe & Mitte, 2009). Such evidence suggests that psychologically healthier individuals may be those who generally strive for more pleasant and less unpleasant emotional experiences.

Contrary to hedonic approaches, instrumental approaches suggest that psychological health is predicated on successful goal pursuit (e.g., Ryff, 1989). Emotions, from this perspective, can be instrumental by facilitating goal-related behaviours (e.g., Parrott, 1993). For example, happiness can promote collaboration, whereas anger can promote confrontation (e.g., Frijda, 1986; Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2004). Psychological health, therefore, should involve more useful and less harmful emotional experiences (e.g., Bonanno, 2001; Tamir, 2009).

If psychological health is predicated on the experience of less harmful and more useful emotions, healthier individuals should strive for instrumental (i.e., goal-consistent) emotions and avoid harmful emotions, whether these emotions are pleasant or unpleasant to experience. Tamir and Ford (2012b) provided preliminary support for this prediction. They found that psychologically healthier individuals reported stronger preferences for anger and stronger preferences for happiness in hypothetical collaborations. However, it has not yet been tested whether healthier people prefer anger when pursuing confrontational goals and prefer happiness when pursuing collaborative goals in their daily life outside the laboratory. People who indicate they would hypothetically prefer to be angry when fighting others may not necessarily prefer to increase their anger when they pursue more mundane confrontational goals in their daily lives. Assessing links between psychological health and emotional preferences as they occur in daily life, therefore, is important for testing the validity of prior findings and establishing their implications outside the laboratory.

The hedonic and the instrumental approaches lead to different predictions regarding links between psychological health and emotional preferences. According to the hedonic approach, psychologically healthier individuals should prefer more pleasant and less unpleasant emotions. In contrast, according to the instrumental approach, psychologically healthier individuals should prefer both pleasant and unpleasant emotions, if they promote the goal they currently pursue. These predictions appear to contradict each other, yet both are theoretically justified. We argue that both approaches are valid, depending on whether emotional preferences are examined in a manner that disregards or focuses on the context in which they occur.

Emotional preferences across and within contexts

The key to reconciling the hedonic and the instrumental approaches, we argue, lies in the degree to which the assessment of emotional preferences is sensitive to context. Emotional preferences across contexts refer to the degree of preference for an emotion that is aggregated across contexts (e.g., preferences for anger during the past week). Emotional preferences within contexts refer to the degree of preference for an emotion within a specific context (e.g., preferences for anger on a day that involves fighting with one’s boss).

In daily life, individuals likely encounter different contexts. Pleasant emotions may be instrumental in some contexts, whereas unpleasant emotions may be instrumental in others. For instance, because anger can promote aggressive action, anger may be useful in contexts that give rise to confrontational goals, but not in contexts that give rise to collaborative goals (e.g., Tamir & Ford, 2012a). In contrast, because happiness promotes prosociality, it may be useful in contexts that give rise to collaborative goals, but not in contexts that give rise to confrontational goals (e.g., Van Kleef et al., 2004). According to the instrumental approach, therefore, psychologically healthier people would prefer to experience more anger in contexts that demand confrontation, but more happiness in contexts that demand collaboration.

When aggregating over time, however, demands that are unique to specific contexts are averaged with potentially opposite demands of other contexts. The degree to which an emotion is useful in one context may be less relevant in determining preferences for that emotion across contexts. Although at any given moment, healthier individuals might be guided by context-specific goals, healthier individuals may still prefer pleasure over pain in the long-run. Thus, over time healthier individuals may prefer to experience pleasant emotions and avoid unpleasant emotions. If so, we would expect psychologically healthier people to prefer less, rather than more, unpleasant emotions, when these emotional preferences are aggregated across contexts.

The distinction between general preferences and context-specific preferences is mirrored in the methods that have been used in the literature to test the hedonic and the instrumental approaches. Studies that provided evidence for the hedonic approach typically measured context-independent emotional preferences, by asking people to what extent they generally want to feel certain emotions, without referring to particular contexts (e.g., Kampfe & Mitte, 2009; Rusting & Larsen, 1995). In contrast, studies that provided evidence for the instrumental approach typically measured context-dependent emotional preferences, by asking people to what extent they want to feel certain emotions in specific contexts (e.g., Tamir & Ford, 2012b).

Accordingly, we hypothesised that psychological health would be linked to weaker preferences for unpleasant emotions and stronger preferences for pleasant emotions, when aggregated across contexts, but to stronger preferences for either unpleasant or pleasant emotions, when examined in contexts in which they might be instrumental.

The current investigation

To test our predictions, we measured emotional preferences and analysed their associations with psychological health. We tested our hypothesis in an experience sampling study, in which we could monitor emotional preferences and daily goals as they occurred naturally outside the laboratory in a large community sample. To measure emotional preferences within contexts, we assessed various tasks that people face in daily life, focusing on tasks that demand some confrontation (i.e., in which anger may be useful) and those that demand some collaboration (i.e., in which happiness may be useful). Instead of using independent measures of emotional preferences within and across contexts, we measured preferences within contexts and then aggregated across them.

To identify such tasks, we first asked participants to list demands that are common in daily life (e.g., “getting a job done”). Then we conducted a pilot study in which a group of novel participants (N = 20) rated the extent to which they perceived such contexts as demanding confrontation (i.e., being aggressive, dominant, strong and firm) and collaboration (i.e., being collaborative, cooperative, submissive and kind). Based on these ratings, we selected the two tasks that were rated as common in daily life and varied systematically in perceived confrontational or collaborative demands. Specifically, “protecting my own interests” was rated as demanding more confrontation than “getting support from others” (Ms = 2.96 and 1.89, respectively, on a 1–5 scale), t(19) = 6.24, p < .001. Whereas “getting support from others” was rated as demanding more collaboration than “protecting my own interests” (Ms = 3.70 and 3.08, respectively, on a 1–5 scale), t(19) = −3.53, p < .005.

In the current study, participants rated the extent to which it was important for them to protect their own interests and to get support from others each day for a period of five days. We also assessed daily preferences for anger and for happiness over the course of those five days. The convergent and predictive validity of the measures of emotional preferences has been established in prior research (e.g., Tamir & Ford, 2012a; Tamir, Ford, & Ryan, 2013). We assessed psychological health by measuring depressive symptoms and global functioning prior to the daily assessments. Finally, to enhance the external validity of our findings, we tested our predictions in a large community sample. To capture sufficient variance in mental health, we recruited participants who had recently experienced personal stress.

We predicted that psychologically healthier individuals would show weaker preferences for anger when averaged across contexts, but stronger preferences for anger when examined within contexts that demand greater confrontation (i.e., the more they needed to protect their own interests). With respect to happiness, we predicted that psychologically healthier individuals would show stronger preferences for happiness when averaged across contexts and stronger preferences for happiness when examined within contexts that demand greater collaboration (i.e., the more they needed to get support from others).

METHODS

Participants

The data collected for this study were derived from a large longitudinal research project.1 Participants were recruited through online advertisement and public postings from the Denver metro area in Colorado and were paid $135 for participation in the entire project. We recruited participants who had experienced a stressful life event (e.g., financial crisis, change in work situation or health problems of significant others) during the past three months.

The study consisted of two phases and only participants who completed both phases were included in the final analyses (N = 174, Mage = 42.51years, SD = 10.86). Participants who completed both phases (74.48%) did not differ significantly from those lost to attrition on indices of psychological health (all ts < 1). 83.3% of participants were Caucasians, 4.0% African-Americans, 1.7% American Indian, 1.7% Asians, 0.6% Pacific Islander, 7.5% were of mixed ethnicities and the rest did not specify race. Approximately 20% of participants reported being previously diagnosed with depression, demonstrating some variance in psychological health.

Procedure

During the first phase of data collection (T1), participants completed online questionnaires, including indices of psychological health and demographic questionnaires. During the second phase (T2), which began approximately one week after the first, participants completed five consecutive days of diaries in which they described a stressful event they experienced that day. They indicated the extent to which the event demanded they protect their own interests (i.e., relatively more confrontational) or get support from others (i.e., relatively more collaborative) and rated their preferences for anger and happiness while experiencing the event. Participants also completed other measures unrelated to the present research question. They completed their ratings on a printed journal every night before going to bed and mailed them to the experimenters at the end of the five-day period.

Measures

Psychological health

We assessed depressive symptoms2 and global functioning. First, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1984) includes 20 items3 (α = .94 in this sample) describing symptoms of depression. Participants rated the degree to which each item described them on a scale of 0 (e.g., “I do not feel sad”) to 3 (e.g., “I am so sad and unhappy that I can’t stand it”). Second, the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) assesses the degree to which an individual carries out activities of daily living in the social, psychological and occupational realms (e.g., “Are you able to communicate verbally with others?”). We used a 23-item modified self-report version (α = .88), in which scores vary from 23 (= persistent danger of hurting self or others) to 207 (= superior functioning in a wide range of activities).

Contextual demands

As an index of contextual confrontational demands, participants rated how important it was for them “to protect their (my) own interests” during the stressful event they had experienced. As an index of contextual collaborative demands, participants rated how important it was for them “to get support from others” (1 = very slightly or not at all; 5 = extremely).

Emotional preferences

Participants rated the extent to which they wanted to experience anger, hostility and happiness during the stressful event, if they could control how they felt that day (1 = slightly, 5 = very). Reliabilities across the five-day period were acceptable (αs = .66, .69 and .73 for anger, hostility and happiness, respectively). Because ratings of anger and hostility were strongly correlated (r = .71, p < .001), we averaged across them to assess preferences for anger.

RESULTS

We first examined the descriptive statistics of our variables when aggregated across contexts, including contextual confrontational demands (M = 2.91, SD = 0.72) and collaborative demands (M = 2.45, SD = 1.45), as well as anger preferences (M = 1.38, SD = 0.72) and happiness preference (M = 2.70, SD = 1.48). The means of BDI (M = 10.19, SD = 9.54) and GAF (M = 148.71, SD = 27.15) were indexed by the total sum of the ratings.

To test whether associations between psychological health and emotional preferences varied across contexts, we used hierarchical linear modelling (HLM; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992). The HLM models consisted of two levels: variables assessed repeatedly over time (Level 1) and individual-level variables (Level 2). Daily-varying variables at Level 1 included daily importance of the confrontational or collaborative contextual demands and emotional preferences. Individual-level variables at Level 2 included indices of psychological health (i.e., depressive symptoms or global functioning). The model tested whether associations between contextual demands and emotional preferences differed as a function of psychological health. The general model was of the following format:

| (Level 1) |

| (Level 2) |

In the model, β0j is expressed as a function of the between-persons intercept (γ00), the contribution of between-persons psychological health (γ01) and a between-persons error term (u0j). We centred contextual demands around each person’s mean across the five days, so β0j is the person’s predicted level of emotional preference on an average day. The within-persons slopes, β1j and β2j, are a function of the mean between-persons slope (γ10 or γ20), the mean between-persons psychological health (γ11 or γ21) and a between-persons error term that captures individual differences in the context-preference slope (u1j or u2j). We tested the intercepts- and slopes-as-outcomes model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), which allows individuals’ intercepts and slopes of emotional preferences to vary on the basis of individual-level characteristics (e.g., psychological health). We ran this model with both confrontational and collaborative contextual demands, separately on depressive symptoms and global functioning, predicting preferences for anger or happiness.

We predicted that on any given day, psychologically healthier individuals would show stronger preferences for anger (but not happiness) the greater the perceived confrontational demands, but that this would not be true for less psychologically healthy individuals. In contrast, we expected psychologically healthier individuals to show stronger preferences for happiness (but not anger) the greater the perceived collaborative demands, but that this would not be true for less psychologically healthy individuals. 4

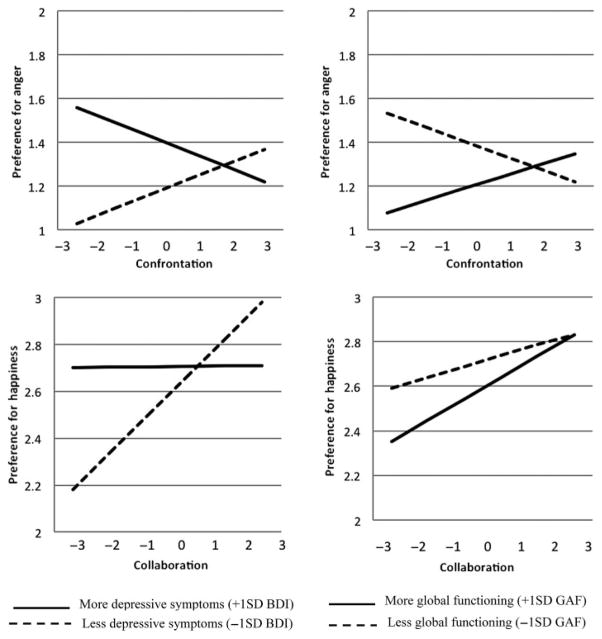

Depressive symptoms

As summarised in Table 1, individuals who experienced more confrontational demands over time had stronger preferences for anger. Furthermore, as reported earlier, individuals higher (vs. lower) in BDI wanted to experience more anger over time. However, as predicted, we found a significant cross-level interaction. As shown in the top left panel of Figure 1 and consistent with the instrumental approach, individuals with less depressive symptoms (i.e., −1 SD from the BDI mean) wanted to feel angrier the greater the contextual demands for confrontation (Level 1). In contrast, individuals with more depressive symptoms (i.e., +1 SD from the BDI mean) wanted to feel less angry in such contexts. Preferences for anger did not vary, however, as a function of collaborative demands.

Table 1.

Summary of coefficient estimates in HLM models predicting emotional preferences

|

Anger

|

Happiness

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | t | Est. | SE | t | |

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| BDI | .01 | .00 | 2.53* | .01 | .01 | 0.60 |

| Confrontational demands | .06 | .03 | 1.91* | .10 | .06 | 1.57 |

| Collaborative demands | −.03 | .03 | −1.13 | .16 | .06 | 2.79* |

| BDI × confrontation | −.01 | .00 | −2.38* | .00 | .00 | −0.03 |

| BDI × collaboration | .00 | .00 | −0.02 | −.01 | .00 | −2.38* |

| Global functioning | ||||||

| GAF | .00 | .00 | −2.24* | .00 | .00 | −0.90 |

| Confrontational demands | −.26 | .12 | −2.29* | .07 | .22 | 0.30 |

| Collaborative demands | .01 | .10 | 0.11 | −.12 | .20 | −0.61 |

| GAF × confrontation | .00 | .00 | 2.39* | .00 | .00 | 0.09 |

| GAF × collaboration | .00 | .00 | −0.44 | .00 | .00 | −0.93 |

Est. = parameter estimates, SE = standard error, t = t-ratio.

p < .05.

Figure 1.

The estimated relationship between daily confrontational demands (top panels) or collaborative demands (bottom panels) and preferences for anger (top panels) and happiness (bottom panels) among individuals higher (+1 SD) and lower (−1 SD) in depressive symptoms and global functioning. Both contextual demands are mean-centred varying from −3 to +3.

With respect to happiness, preferences for happiness were not significantly associated with collaborative demands or BDI when examined across contexts. However, as predicted and consistent with the instrumental approach, we found a significant cross-level interaction between depressive symptoms (Level 2) and collaborative demands (Level 1). As shown in the bottom left panel of Figure 1, individuals with fewer depressive symptoms (i.e., −1 SD from the BDI mean) wanted to feel happier the greater the demands for collaboration. In contrast, individuals with more depressive symptoms (i.e., +1 SD from the BDI mean) wanted to feel less happy in such contexts. No other effects were significant.

Global functioning

As expected and shown in Table 1, better functioning individuals had weaker preferences for anger over time. Unexpectedly, individuals who experienced more confrontational demands had weaker preferences for anger. As predicted, however, this effect was qualified by a significant cross-level interaction between GAF (Level 2) and confrontation (Level 1). As shown in the top right panel of Figure 1, better functioning individuals (i.e., +1 SD from the GAF mean) wanted to feel angrier the greater the contextual demands for confrontation. In contrast, individuals who functioned less well (i.e., −1 SD from the GAF mean) wanted to feel less angry in such contexts. No other effects were significant when predicting anger.

With respect to happiness, contrary to our hypotheses, none of the effects were significant, suggesting that context-sensitive preferences for happiness may be associated with less depressive symptoms, but not necessarily with greater global functioning.

DISCUSSION

Psychologically healthier individuals are those who, on average, experience more pleasant and less unpleasant emotions (Diener et al., 1991). It therefore seems logical that striving for more pleasant and less unpleasant emotional experiences would be a marker of psychological health. This investigation suggests otherwise. Our data show that, consistent with a hedonic approach, psychologically healthier individuals wanted to feel less angry across contexts. However, consistent with an instrumental approach, when they found themselves in situations where anger was potentially instrumental (e.g., situations that are perceived as demanding some confrontation), psychologically healthier individuals (i.e., lower in BDI and higher in GAF) wanted to feel more rather than less angry. Similarly, when they found themselves in situations where happiness was potentially instrumental (e.g., situations that are perceived as demanding some collaboration), psychologically healthier individuals (i.e., lower in BDI) wanted to feel happier. These patterns were context-specific, as preferences for anger varied by confrontational but not by collaborative demands, whereas preferences for happiness varied by collaborative but not by confrontational demands.

These patterns were largely replicated across two measures of psychological health – namely, depressive symptoms and global functioning. These findings were obtained in a community sample, as people reported on their emotional preferences in response to contextual demands in their daily lives. This establishes the external validity of prior findings (e.g., Tamir & Ford, 2012b). Furthermore, our findings demonstrate the relevance of individual differences in emotional preferences for understanding psychological health.

Implications for psychological health

From a theoretical perspective, these findings help reconcile the often opposing predictions of the hedonic and the instrumental approach to psychological health regarding preferences for unpleasant emotions. By examining context-sensitive emotional preferences, we showed that people can be motivated to experience even unpleasant emotions to cope with perceived contextual demands. Psychologically healthier individuals sought to match their emotional states to shifting contextual demands. These findings support the instrumental approach to emotion regulation (e.g., Tamir, 2009), linking the motivation to use emotions effectively to better psychological health. These findings also provide further support for approaches to mental health that emphasises flexibility as a feature of psychological health (e.g., Bonanno & Burton, 2013), demonstrating the importance of flexible motivations in emotion regulation.

From a methodological perspective, our findings suggest that links between individual differences (e.g., depressive symptoms) and emotional constructs (e.g., preferences) can differ depending on whether the emotional constructs are examined in specific contexts or aggregated over time. This conclusion joins prior research that demonstrated the importance of taking time and context into account when examining emotional processes (e.g., Barrett, Robin, Pietromonaco, & Eyssell, 1998).

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, to prefer emotions that fit contextual demands people must understand what the context demands and identify the emotion that best addresses such demands. We assessed emotional preferences in specific contexts that are generally perceived as confrontational or collaborative. Doing so allowed us to assess the same contexts across individuals. However, it leaves open the possibility that people differ either in their interpretation of contextual demands or in their ability to match an emotion to relevant demands. In the future, it would be important to tease these apart.

Second, perceived contextual demands were assessed at the end of each day. Although contextual demands and emotional preferences may span entire days, they could also vary from moment to moment. To assess sensitivity to the immediate context, it would be necessary to examine contextual demands and simultaneous emotional preferences as they occur. Also, future research should examine both emotional preferences and emotional experiences across and within contexts, to test whether the discrepancy between them is smaller among psychologically healthier individuals.

Third, depressive symptoms and global functioning showed similar patterns with respect to preferences for anger, but not for happiness. Whereas individuals with fewer depressive symptoms showed context-sensitive preferences for happiness, individuals who were higher in global functioning did not. Furthermore, we did not find an association between psychological health and preferences for happiness across contexts. One explanation for such findings is that preferences for happiness may be influenced by more factors than preferences for anger (e.g., context-sensitivity and pleasure). Future research can examine these and alternative explanations.

Fourth, our findings suggest that among healthier individuals emotional preferences in specific contexts may be instrumentally driven. One interpretation is that instrumental considerations become less relevant across contexts, making hedonic considerations more pronounced. Another interpretation is that instrumental considerations remain relevant, but are less influenced by goals that are activated in specific contexts and more influenced by goals that are active across contexts. In healthier individuals, such goals may involve strengthening social relations and self-fulfilment (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2001), which anger is less likely to promote. Additional research is needed to test these alternative accounts.

Fifth, what is the mechanism underlying the links between psychological health and context-sensitive emotional preferences? One possibility is that people who are psychologically healthier become able to use their emotions more flexibly to pursue context-sensitive goals. Another possibility is that people who can use their emotions more flexibly to pursue context-sensitive goals become more psychologically healthy. These possibilities could be tested in longitudinal studies in which individuals’ psychological health is assessed at multiple time points. In such studies, it would also be important to examine how people regulate and use their emotions. Finally, we focused on preferences for anger and happiness in confrontational and collaborative contexts. Future research could test the generalisability of our findings by examining other emotions in other contexts and other indices of psychological health, in nonclinical and clinical samples.

Footnotes

Additional data that were collected as part of the larger study were unrelated to the questions examined in the current research project. For example, this included information on emotion regulation strategies (Davis et al., 2014; Shallcross, Ford, Floerke, & Mauss, 2013; Troy, Shallcross, Davis, & Mauss; 2013; Troy, Shallcross, & Mauss, 2013), physiological indices (Hopp, Shallcross, Ford, Troy, Wilhelm, & Mauss, 2013; Kogan et al., 2014; Kogan, Gruber, Shallcross, Ford, & Mauss, 2013), emotional variability (Gruber, Kogan, Quoidbach, & Mauss, 2013), sleep quality (Mauss, Troy, & LeBourgeois, 2013) and automatic emotion regulation (Hopp, Troy, & Mauss, 2011). We report any exclusions that were made, as well as all manipulations and measures that are relevant to this investigation. As this was part of a larger study, the sample size was not based on an a priori determination of effect size.

We included another measure of depression, which is the Diagnostic Inventory for Depression (DID; Zimmerman, Sheeran, & Young, 2004), and all effects were replicated.

We removed an item about suicidality due to Institutional Review Board concerns.

We tested whether there were significant differences between participants who identified themselves as having previously been diagnosed with depression and those who did not by running the HLM analyses separately on each group. We found no significant differences between the groups in any of the analyses.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Robin L, Pietromonaco PR, Eyssell KM. Are women the “more emotional sex?” Evidence from emotional experiences in social context. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:555–578. doi: 10.1080/026999398379565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1984;40:1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::AID-JCLP2270400615>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Emotion self-regulation. In: Mayne TJ, Bonanno GA, editors. Emotions: Current issues and future directions. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 251–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Burton CL. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk A, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models for social and behavioral research: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Davis TS, Mauss IB, Lumian D, Troy AS, Shallcross AJ, Zarolia P, … McRae K. Emotional reactivity and emotion regulation among adults with a history of self-harm: Laboratory self-report and functional MRI evidence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123(3):499–509. doi: 10.1037/a0036962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Sandvik E, Pavot W. Happiness is the frequency, not the intensity, of positive versus negative affect. In: Strack F, Argyle M, Schwarz N, editors. Subjective well-being: An interdisciplinary perspective. New York, NY: Pergamon; 1991. pp. 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ford BQ, Tamir M. Preferring familiar emotions: As you want (and like) it? Cognition and Emotion. 2014;28:311–324. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.823381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH. The emotions. London: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Kogan A, Quoidbach J, Mauss IB. Happiness is best kept stable: Positive emotion variability is associated with poorer psychological health. Emotion. 2013;13(1):1–6. doi: 10.1037/a0030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp H, Shallcross AJ, Ford BQ, Troy AS, Wilhelm FH, Mauss IB. High cardiac vagal control protects against future depressive symptoms under conditions of high social support. Biological Psychology. 2013;93(1):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp H, Troy AS, Mauss IB. The unconscious pursuit of emotion regulation: Implications for psychological health. Cognition and Emotion. 2011;25:532–545. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.532606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. Objective happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kampfe N, Mitte K. What you wish is what you get? The meaning of individual variability in desired affect and affective discrepancy. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan A, Gruber J, Shallcross AJ, Ford BQ, Mauss IB. Too much of a good thing? Cardiac vagal tone’s non-linear relationship with well-being. Emotion. 2013;13:599–604. doi: 10.1037/a0032725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan A, Oveis C, Carr EW, Gruber J, Mauss IB, Shallcross AJ, … Keltner D. Vagal activity is quadratically related to prosocial traits, prosocial emotions, and observer perceptions of pro-sociality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0037509. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Tamir M. Emotion goals: How their content, structure, and operation shape emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. The handbook of emotion regulation. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2014. pp. 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Troy AS, LeBourgeois MK. Poorer sleep quality is associated with lower emotion-regulation ability in a laboratory paradigm. Cognition and Emotion. 2013;27:567–576. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.727783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott WG. Beyond hedonism: Motives for inhibiting good moods and for maintaining bad moods. In: Wegner DM, Pennebaker JW, editors. Handbook of mental control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1993. pp. 278–305. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. Hierarchical linear models. [Google Scholar]

- Rusting CL, Larsen RJ. Moods as sources of stimulation: Relationships between personality and desired mood states. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;18:321–329. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)00157-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52(1):141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shallcross AJ, Ford BQ, Floerke VA, Mauss IB. Getting better with age: The relationship between age, acceptance, and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:734–749. doi: 10.1037/a0031180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M. What do people want to feel and why? Pleasure and utility in emotion regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01617.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M, Bigman Y, Rhodes E, Salerno J, Schreier J. Expected usefulness of emotions shapes emotion regulation, experience, and decision-making. 2014 doi: 10.1037/emo0000021. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M, Ford BQ. When feeling bad is expected to be good: Emotion regulation and outcome expectancies in social conflicts. Emotion. 2012a;12:807–816. doi: 10.1037/a0024443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M, Ford BQ. Should people pursue feelings that feel good or feelings that do good? Emotional preferences and well-being. Emotion. 2012b;12:1061–1070. doi: 10.1037/a0027223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M, Ford BQ, Ryan E. Nonconscious goals can shape what people want to feel. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2013;49:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AS, Shallcross AJ, Davis TS, Mauss IB. History of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is associated with increased cognitive reappraisal ability. Mindfulness. 2013;4:213–222. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AS, Shallcross AJ, Mauss IB. A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychological Science. 2013;24:2505–2514. doi: 10.1177/0956797613496434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Knutson B, Fung HH. Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:288–307. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleef GA, De Dreu CKW, Manstead ASR. The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations: A motivated information processing approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:510–528. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JV, Heimpel SA, Manwell LA, Whittington EJ. This mood is familiar and I don’t deserve to feel better anyway: mechanisms underlying self-esteem differences in motivation to repair sad moods. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:363–380. doi: 10.1037/a0012881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Sheeran T, Young D. The diagnostic inventory for depression: A self-report scale to diagnose DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60(1):87–110. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]