Abstract

Background

Significant advances in the development of SMN-restoring therapeutics have occurred since 2010 when very effective biological treatments were reported in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. As these treatments are applied in human clinical trials, there is pressing need to define quantitative assessments of disease progression, treatment stratification, and therapeutic efficacy. The electrophysiological measures Compound Muscle Action Potential and Motor Unit Number Estimation are reliable measures of nerve function. In both the SMNΔ7 mouse and a pig model of spinal muscular atrophy, early SMN restoration results in preservation of electrophysiological measures. Currently, clinical trials are underway in patients at post-symptomatic stages of disease progression. In this study, we present results from both early and delayed SMN restoration using clinically-relevant measures including electrical impedance myography, compound muscle action potential, and motor unit number estimation to quantify the efficacy and time-sensitivity of SMN-restoring therapy.

Methods

SMAΔ7 mice were treated via intracerebroventricular injection with antisense oligonucleotides targeting ISS-N1 to increase SMN protein from the SMN2 gene on postnatal day 2, 4, or 6 and compared with sham-treated spinal muscular atrophy and control mice. Compound muscle action potential and motor unit number estimation of the triceps surae muscles were performed at day 12, 21, and 30 by a single evaluator blinded to genotype and treatment. Similarly, electrical impedance myography was measured on the biceps femoris muscle at 12 days for comparison.

Results

Electrophysiological measures and electrical impedance myography detected significant differences at 12 days between control and late-treated (4 or 6 days) and sham-treated spinal muscular atrophy mice, but not in mice treated at 2 days(p<0.01). EIM findings paralleled and correlated with compound muscle action potential and motor unit number estimation (r=0.61 and r=0.50, respectively, p<0.01). Longitudinal measures at 21 and 30 days show that symptomatic therapy results in reduced motor unit number estimation associated with delayed normalization of compound muscle action potential.

Conclusions

The incomplete effect of symptomatic treatment is accurately identified by both electrophysiological measures and electrical impedance myography. There is strong correlation between these measures and with weight and righting reflex. This study predicts that measures of compound muscle action potential, motor unit number estimation, and electrical impedance myography are promising biomarkers of treatment stratification and effect for future spinal muscular atrophy trials. The ease of application and simplicity of electrical impedance myography compared with standard electrophysiological measures may be particularly valuable in future pediatric clinical trials.

Keywords: Spinal muscular atrophy, biomarker, survival motor neuron, antisense oligonucleotide, electrical impedance myography, motor unit number estimation, electromyography, clinical trials, gene therapy, pharmacodynamics

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive motor neuron disorder caused by homozygous deletion or mutation of the SMN1 gene (Lefebvre et al., 1995). Severity of the disease is related to the copy number of a second closely related gene, SMN2, which produces insufficient levels of SMN protein levels for normal motor neuron function and survival (Burghes and Beattie, 2009). SMA is the most common genetic causes of infant death (Roberts et al., 1970). Beginning in 2010, the first highly successful preclinical therapies for SMA including self-complementary adeno-associated virus subtype 9 to transfer the SMN gene (scAAV9-SMN), antisense oligonucleotides, and small molecules were reported in mouse models of the disease (Bevan et al., 2010; Dominguez et al., 2011; Foust et al., 2010; Naryshkin et al., 2014; Palacino et al., 2015; Passini et al., 2011; Valori et al., 2010). The field of SMA has since seen impressive progress towards implementation of several preclinical therapies to the clinic (reviewed in (Arnold and Burghes, 2013; Arnold et al., 2015; Kolb SJ, 2011). Now biomarkers to evaluate the effect of therapy in SMA are urgently needed to test potential treatments and accelerate clinical trials. Various forms of potential biomarkers have been studied including imaging modalities such as ultrasound and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, molecular markers, electrical impedance myography (EIM), and electrophysiological measures including compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and motor unit number estimation (MUNE) (Finkel et al., 2012; Finkel et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2014; Kaufmann et al., 2012; Lewelt et al., 2010; Pillen et al., 2011; Poruk et al., 2012; Renusch et al., 2015; Rutkove et al., 2012b; Rutkove et al., 2010; Swoboda et al., 2005).

In several clinical studies CMAP and MUNE have shown strong correlation with severity of disease, age, and functional status, supporting their potential as prognostic biomarkers (Finkel, 2013; Finkel et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2014; Kaufmann et al., 2012; Lewelt et al., 2010; Swoboda et al., 2005). Furthermore, in natural history studies CMAP and MUNE have provided important insight into the onset and progression of neuromuscular deficits in SMA (Finkel et al., 2014; Kaufmann et al., 2012; Swoboda et al., 2005). These electrophysiological measures in patients with SMA have helped define the presence of a pre-symptomatic period early in the course of the disease, when CMAP and MUNE are either normal or close to normal. This is particularly pertinent to the implementation of therapeutics as mouse studies have shown the greatest therapeutic benefit is achieved when administered pre-symptomatically (Foust et al., 2010; Robbins et al., 2014). Unfortunately, this pre-symptomatic period is followed by rapid loss of neuromuscular function indicated by plummeting electrophysiological responses (Finkel, 2013; Finkel et al., 2014; Swoboda et al., 2005). After a period of progressive decline, clinical features and electrophysiological markers show remarkable stability, and it is unlikely that SMN restoration will have much impact at later stages of disease progression (Kang et al., 2014; Swoboda et al., 2005).

EIM is a more recently developed biomarker that has shown promise in SMA (Rutkove, 2009; Rutkove et al., 2012b; Rutkove et al., 2010; Srivastava et al., 2012). As with other electrical bioimpedance-based applications, e.g. whole-body impedance (NIH, 1996) or impedance cardiography (Kubicek et al., 1966), in EIM a low-intensity (<1 mA) alternating electrical current is passed through a specific region of muscle or group of muscles using two surface electrodes and the consequent voltage response is measured with two additional surface electrodes. EIM values correlate with muscle strength testing in SMA patients(Rutkove et al., 2010), and older children with SMA show little evidence of muscle maturation over time, as assessed by EIM, as compared to healthy individuals(Rutkove et al., 2012b). The findings of EIM in younger cohorts of SMA and in patients during earlier phases of the disease have yet to be defined, but natural history studies applying EIM to younger children in the more progressive phase of the disease and in therapeutic trials are currently under way (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01736553 and NCT02122952). Despite this promising work demonstrating relationships between EIM and standard functional, electrophysiological and histological data in SMA and other animal models (Li et al., 2012), no studies have attempted to determine whether EIM can quantify a treatment effect in a neuromuscular disorder.

Currently, there are several ongoing clinical trials investigating safety and efficacy of SMN-restoring therapeutics including gene therapy to replace the SMN, as well as small molecules and antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapies to increase SMN production from the SMN2 gene. In these early clinical therapeutic trials, it is unknown how the timing of SMN intervention in relation to timing of the loss of motor neuron function will impact therapeutic response. Furthermore, due to the rapid decline in motor neuron function in the most severe SMA cases, the time from disease diagnosis to therapeutic intervention will greatly affect the number of functional motor units remaining and thus the potential benefit of any therapy. Therefore, there is an urgent need to study the neuromuscular impact of delayed SMN restoration and to define biomarkers that indicate when SMN restoration will be most effective. Until newborn screening of SMA is universal, post-symptomatic SMN restoration will be commonplace. Therefore, in this study, we sought to compare the neuromuscular effects of pre-symptomatic versus symptomatic SMN restoration on SMA phenotype.

Materials and methods

Animals

All studies were approved by the animal institutional care and use committee of The Ohio State University. For this study we used a well-characterized model of SMA, the SMAΔ7 mouse (Jackson Lab stock number 5025) (Le et al 2005). The SMNΔ7 mouse, although phenotypically normal at birth, develops progressive weakness becoming overt at about 6 days of age and dies at approximately 2 weeks(Butchbach et al., 2007; Le et al., 2005). SMNΔ7 mice (SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+; Smn−/−) were generated as previously described, by crossing phenotypically normal heterozygote mice (SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+; Smn+/−). Heterozygote mice (SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+; Smn+/−) were used as controls.

Intracerebroventricular ASO therapy

SMNΔ7 mice were treated via intracerebroventricular injection with 40 µg of morpholino ASOs directed against ISS-N1 to increase full-length SMN protein production from SMN2 as previously described by Porensky et al. (Porensky et al., 2012) This treatment increases median lifespan of the SMNΔ7 mouse from 2 weeks to over 100 days with a single injection (Porensky et al., 2012). One set of SMA mice received treatment at P2 or earlier (P2-ASO), a second group of SMA mice received treatment at P4 (P4-ASO), a third group of SMA mice received ASO treatment at P6 (P6-ASO), a third group SMA mice received scrambled ASO (SMA), and a fourth group consisted of heterozygous control animals treated with ASO or scrambled ASO as described above (Control).

Anesthesia and animal preparation

Neonatal mice were anesthetized using cryoanesthesia prior to intracerebroventricular injections. For electrophysiological and EIM studies, mice were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane and placed in the prone position on a low noise, thermostatically-controlled warming plate (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) set to maintain temperature at 37°C. The hind limbs were extended at the knees and abducted at the hips with adhesive tape. O2 flow was set at 1 L/min and the percentage isoflurane adjusted for adequate sedation, with care taken to avoid over-sedation. Although the effects of genotype and treatment on animal size could not be controlled for, the evaluator for electrophysiological, EIM, and behavioral testing (WDA) was blinded to genotype and treatment.

Electrophysiological measurements

CMAP and MUNE measurements were performed as previously described at P12, P21, and P30 (Arnold 2015; Arnold et al., 2014; McGovern et al., 2015). Briefly, the right sciatic nerve was stimulated with a pair of insulated 28 gauge monopolar needles (Teca, Oxford Instruments Medical, NY) placed in proximity to the sciatic nerve in the proximal hind limb. Recording electrodes consisted of a pair of fine ring wire electrodes (Alpine Biomed, Skovlunde, Denmark). The active recording electrode (E1) was placed distal to the knee joint over the proximal portion of the triceps surae muscle and the reference electrode (E2) over the metatarsal region of the foot. A disposable strip electrode (Carefusion, Middleton, WI) was placed on the contralateral hind limb to serve as the ground electrode.

For CMAP, supramaximal responses were generated maintaining stimulus currents <10 mA and baseline-to-peak amplitude measurements made. For MUNE, an incremental stimulus technique similar to that described was utilized (Arnold 2015; McGovern et al., 2015). Submaximal stimulation was utilized to obtain ten incremental responses to calculate the average single motor unit potential (SMUP) amplitude. The first increment was obtained by delivering square wave stimulations at 1 Hz at an intensity between 0.21 mA to 0.70 mA to obtain the minimal all-or-none SMUP response. If the initial response did not occur with stimulus intensity between 0.21 mA and 0.70 mA, the stimulating cathode position was adjusted either closer or farther away from the position of the sciatic nerve in the proximal thigh to decrease or increase the required stimulus intensity, respectively. This first incremental response was accepted if three duplicate responses were observed. To obtain the subsequent incremental responses the stimulation intensity was adjusted in 0.03 mA steps and incremental responses were distinguished visually in real-time to obtain nine additional increments. To be accepted, each increment was required to be: (1) observed for a total of three duplicate responses, (2) to be visually distinct from the prior increment, and (3) to be at least 25 µV larger than the prior increment. The peak-to-peak amplitude of each individual incremental response was calculated by subtracting the amplitude of the prior response. The 10 incremental values were averaged to estimate average peak-to-peak single motor unit potential (SMUP) amplitude. The maximum CMAP amplitude (peak-to-peak) was divided by the average SMUP amplitude to yield the MUNE. At P80, needle electromyography of the right gastrocnemius was performed in SMA mice treated at P4 as previously described(Arnold et al., 2014).

EIM measurements

EIM requires four electrodes in close approximation to one another. Given the very small size of the animals a number of alterations were made to the electrode array compared to measurements on adult mice. First, in lieu of using a surface electrode array, a 4-electrode needle array was created by employing 4 insulated monopolar needle electrodes (Natus, Inc, cat# 902-DMG50-S, Middleton, Wisconsin). The needle electrode spacing was of about 1 mm (Figure 1). The back ends of the needle electrodes were stripped off their connectors and soldered to wires that connected to the EIM 1103 system cradle.

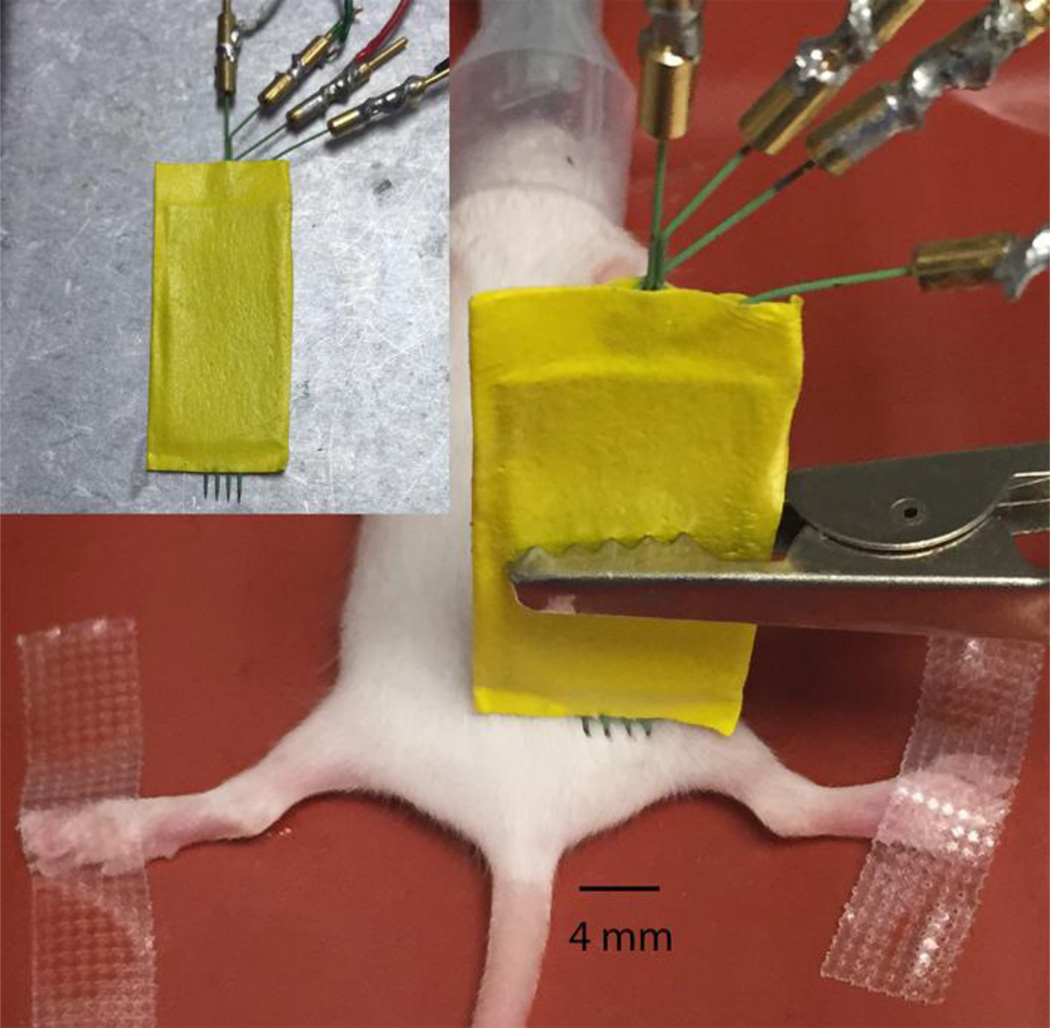

Figure 1.

Measurement set up for acquisition of electrical impedance myography (EIM) data in the SMAΔ7 mouse; inset shows a close up of the array in the muscle. The needle electrode array was placed approximately at the biceps femoris muscle; the outer two electrodes injected current into the muscle, the inner two measured the consequent voltage response.

For most EIM work in rodents to date, the gastrocnemius muscle has been studied(Ahad et al., 2009; Ahad and Rutkove, 2009; Li et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2014d; Li et al., 2012). However, given the challenges in measuring such a small muscle in these young animals, we chose to measure the biceps femoris, the array being placed in the proximal posterior thigh in all animals (Figure 1). The array was held in place using alligator clips attached to ball and socket armatures held secure with an iron base (Helping Hands by RadioShack, Fort Worth, TX). For animals that underwent both electrophysiological measures and EIM, CMAP and MUNE were performed first.

Muscle resistance and reactance were measured at 37 frequencies from 8 kHz to 1 MHz on P12 using an impedance analyzer (EIM 1103, Skulpt, Inc, San Francisco, CA). The phase was found from the angle defined by the reactance and resistance values for each frequency, i.e. phase = arctan (Reactance / Resistance)(Eisenberg, 2010; Grimnes and Martinsen, 2015). Single-frequency data at 50 kHz were correlated to CMAP and MUNE. Further, the frequency at which the peak reactance occurred was identified by fitting the multi-frequency data.(Sanchez et al., 2013) The dependence of the reactance as a function of frequency was found from the averaged parameters.

Behavioral testing

Righting reflex was performed at P12 by placing each mouse in the supine position on a stainless steel surface and recording the latency required for righting(Butchbach et al., 2007). An upper limit of 60 seconds was employed. Weight and survival were monitored daily until day 21 and 60, respectively.

Statistical analyses

For comparison between groups, ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc tests were utilized to determine significance among the groups. For correlation analysis, standard Pearson test was performed. Weight curve analysis was completed with Statmod(Baldwin et al., 2007; Elso et al., 2004). For all studies, p < 0.05 was considered significant. All values shown as mean±standard deviation.

Results

Effect of treatment and treatment timing as measured by electrophysiology at P12

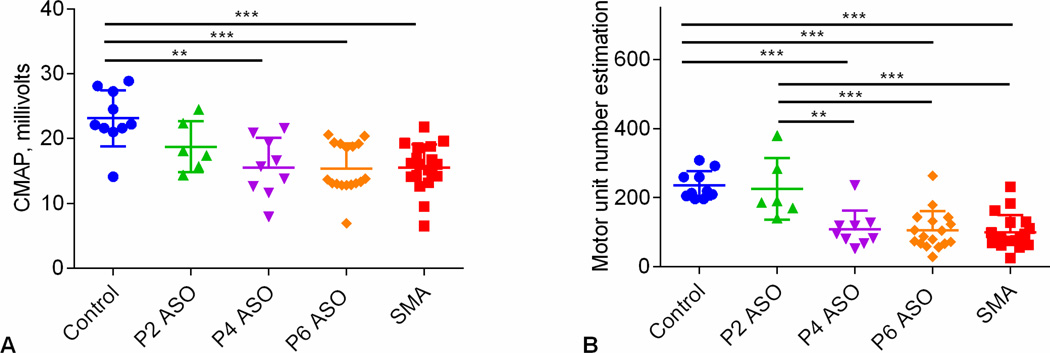

Figure 2 shows that CMAP and MUNE at P12 are reduced in Sham-treated (SMA) and Late-treated SMA (P6-ASO) versus Control mice. Similar to what we previously have shown with early therapy on day of birth, CMAP in early-treated SMA mice (P2-ASO) was not statistically different compared with sham-treated SMA or late-treated SMA (P4-ASO and P6-ASO)(Arnold et al., 2014). MUNE was preserved in early-treated SMA (P2-ASO) and identified differences between early-(P2-ASO) and late-treated (P6-ASO) animals.

Figure 2.

A. Compound muscle action potential (CMAP). Comparison of CMAP data at P12 in controls (n=10), SMA (n=19), P2-ASO (n=6), P4-ASO (n=9), and P6-ASO (n=17) showed significant differences (p=0.001). Post-hoc Tukey tests demonstrated significant differences between control and late-treated SMA mice (P4 and P6-ASO) and shamtreated animals, but not the early treated SMA mice (P2-ASO). B. Motor unit number estimation (MUNE). Comparison of MUNE at P12 in all 4 groups of animals showed statistically significant difference. MUNE demonstrated significant differences in control versus late-treated SMA (P4 and P6-ASO) and sham-treated mice and between ASO-treated mice and late-treated (P4 and P6-ASO) and sham-treated SMA mice. *, p<0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

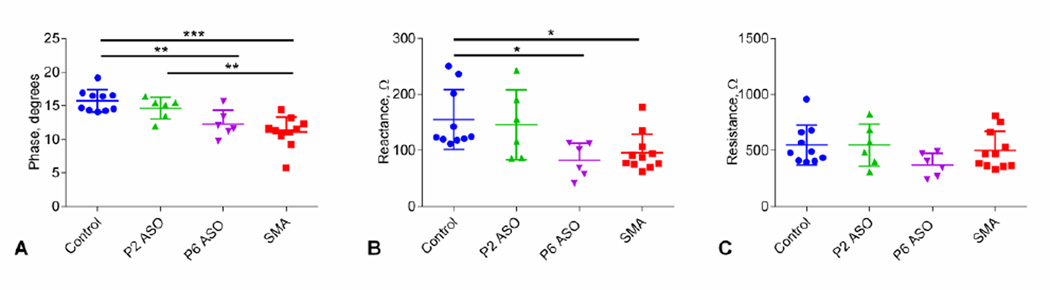

Effects of treatment and treatment timing as measured by EIM at P12

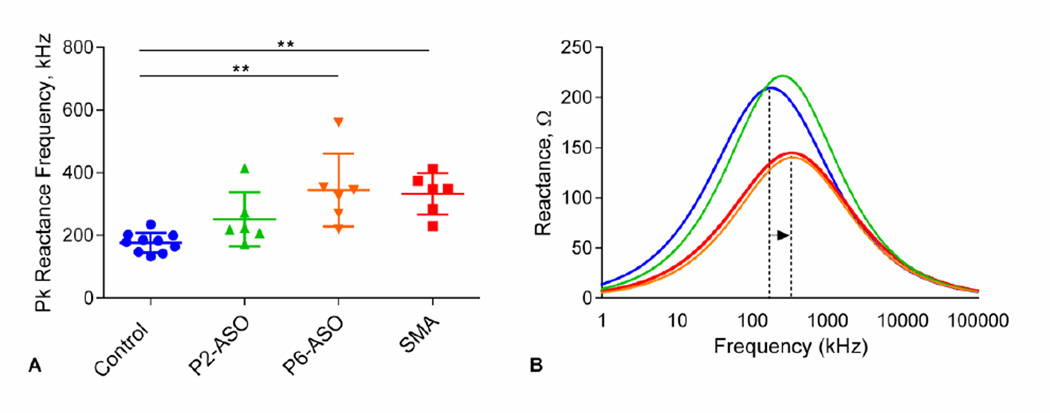

Results for EIM of the biceps femoris are shown in Figure 3. EIM measures of phase (Figure 3A) and reactance at 50 kHz (Figure 3B) were reduced in sham-treated SMA and P6-ASO-treated SMA mice. Similar to MUNE, phase and reactance values in earlyt-reated mice showed no differences compared to controls and were increased compared with late-treated and sham-treated SMA mice. In contrast to phase and reactance, resistance (Figure 3C) was unchanged between any of the groups. In addition to this single frequency data, multi-frequency analysis demonstrated significant differences between peak reactance frequency for control mice versus late-treated (P6-ASO) and sham-treated SMA mice (p<0.01), but not to early treated (P2-ASO) SMA mice (Figure 4A). Similarly, the overall, fitted multifrequency data (Figure 4B) demonstrate that the peak reactance values were significantly shifted to higher values in both late/sham-treated SMA mice compared to controls (p<0.01).

Figure 3.

Single-frequency group comparison A. 50 kHz Phase. Comparison of phase data at P12 in all 4 groups of animals. Similar to compound muscle action potential (CMAP), post-hoc Tukey tests demonstrated significant differences between control and late-treated (P6-ASO) and sham-treated SMA mice, but not the early treated (P2-ASO) SMA mice. B. 50 kHz Reactance. Comparison of reactance showed the same pattern of differences between groups as shown for phase and CMAP. C. 50 kHz Resistance. There are no significant differences between groups for resistance. *, p< 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

Figure 4.

A. Peak frequency comparison from the multi-frequency analysis. Statistical tests show significant differences between control and late-treated (P6-ASO) and sham-treated SMA mice, but not to early treated (P2-ASO) SMA mice. B. Reactance spectrum found from the averaged model parameters. The dotted lines exemplify the shift in the peak reactance frequency for the groups that were significantly different in A. **, p < 0.01

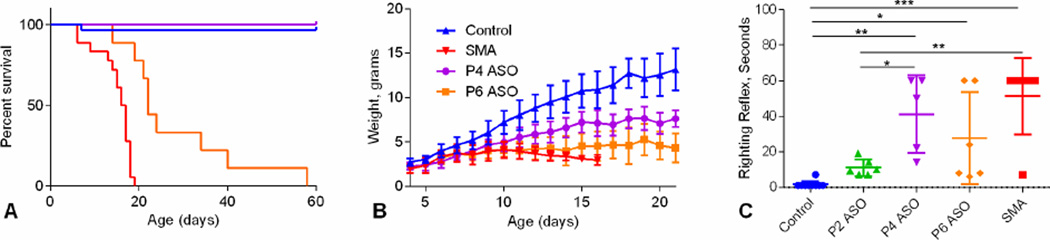

Weight and behavioral analysis following treatment

Figure 5A shows survival analysis in late treated SMA mice. In contrast to electrophysiological measures, survival was increased in P4-ASO versus P6-ASO and SMA as well as P6-ASO versus SMA (P<0.001). Weight was reduced in P4-ASO (P<0.001) and P6-ASO (p<0.001) treated SMA mice and sham-treated SMA mice (p<0.001) compared to Controls (Figure 5B). P4-ASO mice demonstrated increased weight compared with SMA mice (p<0.001) but not P6-ASO treated mice. There was no difference between sham-treated SMA and P6-ASO-treated SMA mice nor P4-ASO and P6-ASO. There was increased latency for righting in late-treated and sham-treated SMA mice compared to control mice (Figure 5B and C). There was also increased latency for righting in P4-ASO SMA and SMA mice compared with P2-ASO (p<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively).

Figure 5.

Survival, weight, and righting reflex latency. A. Median survival for controls (n=29) and P4-ASO SMA (n=5) was greater than 60 days, 22 days for P6-ASO SMA (n=9), and 16.5 days for sham-treated SMA mice (n=18). B. Weight curves from P4-P30 in controls (n=21), P4-ASO (n=7), P6-ASO (n=8), and SMA (n=15). C. Comparison of righting reflex latency in controls (n=10), P2-ASO (n=6), P4-ASO (n=5), P6-ASO (n=6), and SMA (n=11). There are significant differences between control and SMA (n=6) (p<0.001), P4-ASO (n=5) (p<0.001), and P6-ASO (n=6) (p<0.05) and between P2-ASO and SMA (p<0.01) and P4 (p<0.05).*, p<0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

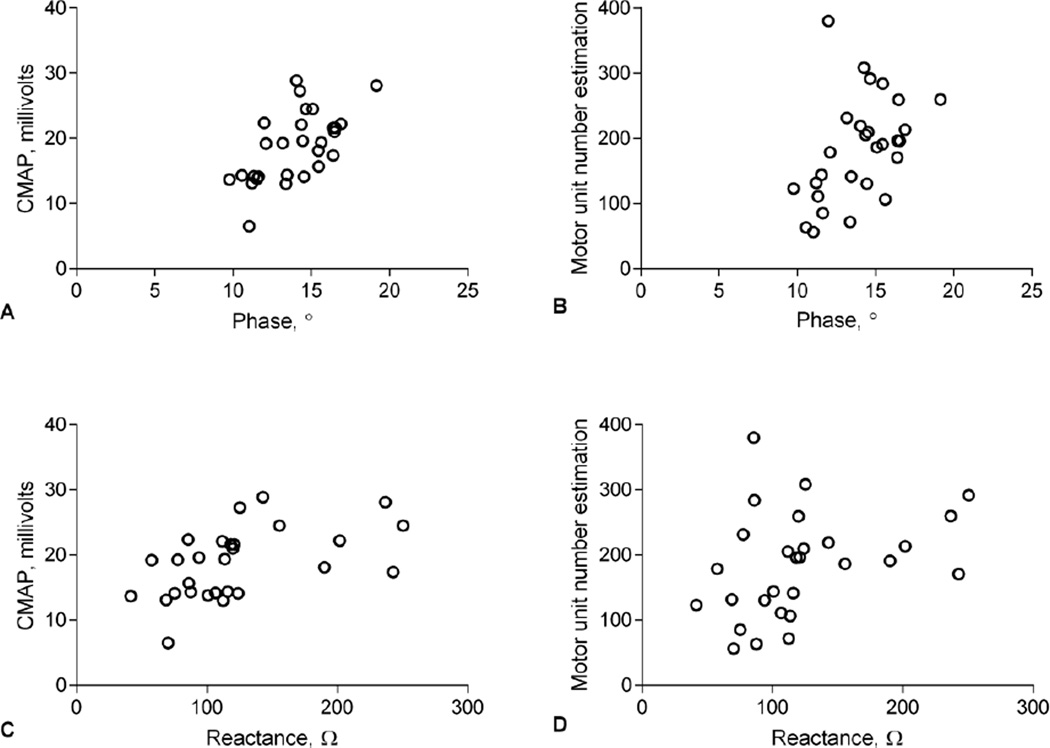

Correlations between EIM, electrophysiology and behavioral studies

There were strong correlations between EIM, CMAP, and MUNE incorporating all the data from all the groups (Figure 6). As noted, phase and reactance at 50 kHz correlated well with both CMAP and MUNE, although the correlation with CMAP was stronger. EIM and electrophysiology measures correlated well with behavioral testing (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Pearson correlation analyses showing correlation of EIM 50 kHz phase to CMAP (A) (r=0.616, p<0.001) and MUNE (B) (r=0.451, p<0.05) and 50 kHz Reactance to CMAP (C) (r=0.516, p<0.01) but not MUNE (D) (r=0.342, p=0.07).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) of 50 kHz phase, and 50 kHz reactance, and electrophysiological measures with weight and righting reflex at P12.

| Weight | Righting Reflex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-value | r | p-value | |

| Phase | 0.638 | <0.001 | −0.556 | <0.001 |

| Reactance | 0.517 | 0.004 | −0.353 | 0.065 |

| CMAP | 0.702 | <0.001 | −0.598 | <0.001 |

| MUNE | 0.658 | <0.001 | −0.578 | 0.001 |

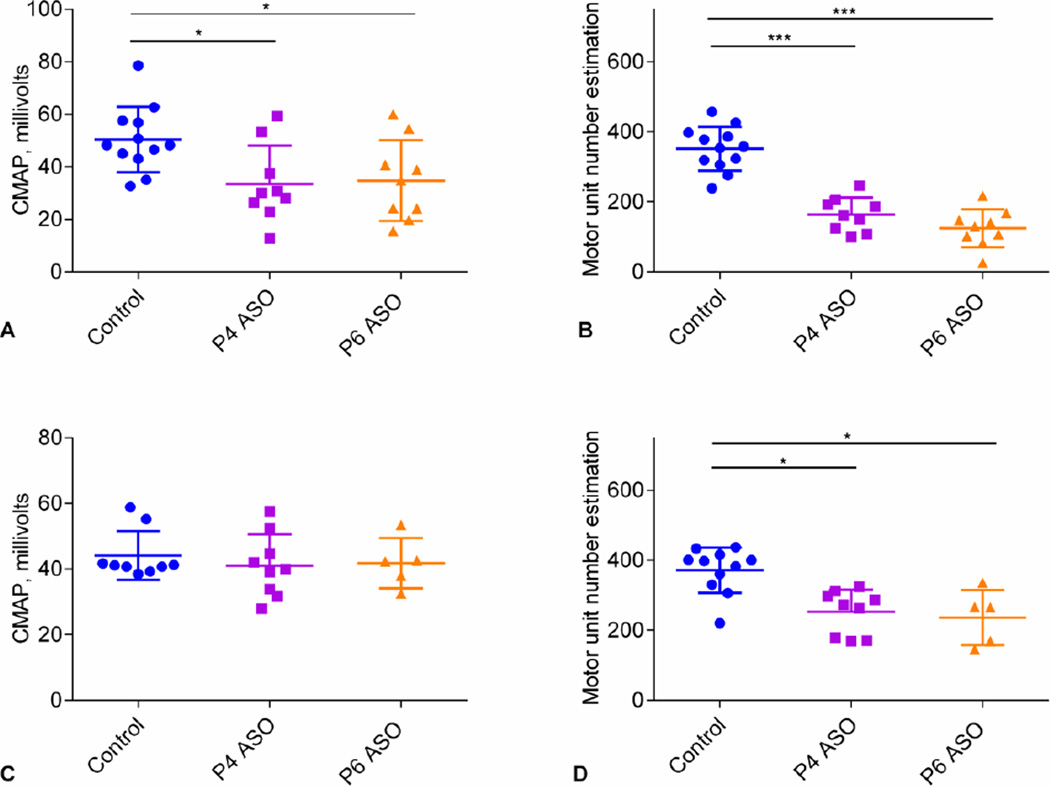

Longitudinal electrophysiological findings following delayed SMN restoration

In addition to measures at P12, longitudinal electrophysiological recordings were performed at P21 and P30 in SMA mice treated at P4 (P4-ASO) and (P6-ASO) to investigate the characteristics of motor unit responses over time. At P21 both P4-ASO and P6-ASO SMA mice showed reduced CMAP (p<0.05) and MUNE (p<0.001) (Figure 7A and 6B). At P30, CMAP responses were no longer reduced in SMA mice treated at P4 and P6 (Figure 7C), but MUNE were not recovered (p<0.05) (Figure 7D). SMA mice treated at P4 (P4-ASO) demonstrated fibrillations in the gastrocnemius at P80 (n=3).

Figure 7.

Longitudinal CMAP and MUNE measures at P21 and P30 in controls and mice treated with delayed SMN restoration. 6 A–B. At P21 both P4-ASO (33.4±14.6 mV; 164±48; n=9) and P6-ASO SMA mice (34.7±15.4 mV; 124±54; n=9) show reduced CMAP and MUNE compared to control. (50.4±12.4 mV; p<0.05 and 352±63; n=12; p<0.001). C. At P30, MUNE continues to be reduced in P4-ASO (253±63; n=9) and P6-ASO (236±78; n=5) compared with controls (371±65; n=9; p<0.05). D. At P30 CMAP is no longer reduced in SMA mice treated at P4 (41.0±9.6mV; n=9) and P6 (41.8±7.7 mV; n=5) versus control (44.1±7.4 mV; n=9). * p<0.05; ***, p < 0.001

Discussion

This study confirms the time dependency of SMN restoration for effective rescue of motor neuron function. EIM has shown sensitivity to disease status in a variety of neuromuscular conditions including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Rutkove et al., 2012a; Rutkove et al., 2007), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Rutkove et al., 2014), and disuse atrophy (Li et al., 2013; Tarulli et al., 2009). The only previous evidence of EIM data changing in respect to therapy however has been in disuse atrophy, in which subjects demonstrated improved measures after restarting full weight bearing after an ankle fracture (Tarulli et al., 2009), and in patients with cervical dystonia in whom botulinum therapy produced greater symmetry of EIM values in sternocleidomastoid and trapezius (Lungu et al., 2011). Thus, this study demonstrates, for the first time, that EIM measurements are sensitive to treatment effects in a primary neuromuscular disease.

In this study, CMAP and MUNE at P12 show good correlation with weight, survival, and righting reflex. CMAP is a measure of the total electrophysiological output from a group of muscles, in this study the sciatic-innervated triceps surae. MUNE is a measure of the number of functional motor neurons determined by estimating the number of functional motor units supplying a muscle or group of muscles (McComas et al., 1971; Shefner, 2001). Our prior study showed that untreated SMNΔ7 mice have reduced CMAP by P6 when motor phenotype becomes overt (Arnold et al., 2014). We previously demonstrated that postnatal but presymptomatic SMN restoration leads to preserved electrophysiological function in the SMNΔ7 mouse (Arnold et al., 2014) and more recently in a pig model of SMA (Duque et al., 2015).

This study expands upon previous studies to examine the effects of post-symptomatic SMN restoration by including mice that were treated with ASO at two delayed time points, P4 or P6. SMN restoration with ASO administered at P4 and P6 results in reduced number of motor units rescued (reduced MUNE) examined at P12, P21, and P30. In contrast, the functional neuromuscular output shows improvement over time (normalization of CMAP), consistent with the compensatory enlargement of the motor units that are rescued. Fibrillation potentials are a classic feature of SMA (Buchthal and Olsen, 1970; Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz and Karwanska, 1986) as well as other disorders associated with denervation of muscle fibers (Willmott et al., 2012). In SMA mice treated with ASO on P0, needle electromyography of hindlimb muscles demonstrated no fibrillation potentials at P90(Arnold et al., 2014). In this study, fibrillations were noted in mice treated with ASO at P4 when tested at P80. Importantly, detection of fibrillations at later time points in symptomatically-treated SMA mice implies increased susceptibility of the motor neuron pool to degeneration and could be related to losing the effect of the single ASO dose over time.

In contrast to human SMA, mouse models of SMA demonstrate several additional pathological features that are only rarely reported in a few patients with the most severe forms of the disease (type 0 SMA with a single copy of SMN2) (Araujo et al., 2009; Bevan et al., 2010; Distefano et al., 1994; Harding et al., 2015; Rudnik-Schoneborn et al., 2010; Shababi et al., 2012; Shababi et al., 2014). Therefore, loss of motor neuron function and degeneration is the most clinically relevant feature in SMA models. We recently demonstrated that motor neuron function is dependent upon high SMN levels in neurons (McGovern et al., 2015). In these studies, electrophysiological function of the motor unit pool is fully rescued when SMN is increased in only motor neurons (on the background of SMNΔ7 levels of SMN in other cell types), and similarly, loss of motor unit function in mice with low levels of SMN in only motor neurons is similar to that noted in ubiquitously low SMN levels (i.e. SMNΔ7 SMA mice) (McGovern et al., 2015). Thus, the findings of this previous study combined with the present study provide strong evidence that increased SMN levels in motor neurons at presymptomatic time points will be required for the most successful treatment of SMA.

The mechanism of disease change as measured by EIM in SMA is uncertain, but a variety of effects may be occurring in the muscle to explain these changes and how they relate to CMAP and MUNE. CMAP and MUNE allow a functional assessment of the motor unit pool supplying a muscle or group of muscles, and thus these measures are reduced in the setting of denervation. Thus reduction in muscle fiber size due to motor neuron loss and muscle fiber atrophy could explain a reduction in reactance and phase as both reactance and phase are both dependent on the muscle membrane area and cell size. Resistance might be expected to increase slightly due to reduced muscle volume. Resistance could also theoretically decrease to some extent due to edema, which is well-known to occur in SMA mouse models.(Hsieh-Li et al., 2000) In the current studies there was a slight, but non-significant, reduction in resistance in the sham-treated and latetreated SMA mice compared with the early-treated and control animals.

For the EIM measurements in this study, the biceps femoris was chosen given its larger size. All in vivo animal work reported to date, for example, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and muscular dystrophy mice, has been performed on adult animals and has used surface electrode arrays, analogous to those used in human studies (Ahad and Rutkove, 2010; Ahad et al., 2009; Ahad and Rutkove, 2009; Li et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2014d; Li et al., 2013; Li et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2015). Prior studies have demonstrated that subcutaneous tissue contributes little to the measurement of EIM reactance(Sung et al., 2013). Since denervation in SMA animal models is to some extent muscle dependent (Ling et al., 2012), it is certainly possible that inconsistencies with placement could lead to variations in the obtained data. However, given the small size of these mice, with the average 12-day-old animal weighing only ~10 grams, it was necessary to employ needle electrodes.

In addition to demonstrating the ability of EIM at 50 kHz to detect a treatment effect, we found that additional useful information is revealed from multifrequency analysis. The frequency reactance plot (Fig 4B) provides an overview of the differences in EIM data between the control/early-treated and late/sham treated animals. The peak, or central, frequency (shown by arrows in Figure 4A) is inversely related to myofiber size (Sekine et al., 2015). Thus, these results suggest that early treated and control mice had larger average myofiber size as compared to those treated with sham or symptomatic ASO therapy. Additionally, EIM phase and reactance correlate well with CMAP and MUNE confirming previous work in a much milder SMA mouse model where EIM correlated moderately with CMAP (in the previous study with r = 0.44, p = 0.04)(Li et al., 2014a). In summary, the therapeutic responsiveness of EIM in SMA suggests that these techniques will hold similar benefit in the treatment of other neuromuscular disorders.

For the first time we have shown that EIM phase and reactance are sensitive to both SMA phenotype and to drug effect in a severe mouse model of SMA. EIM phase and reactance correlate remarkably well to accepted electrophysiological measures. The value of standard electrophysiological measures, such as CMAP and MUNE, is that these measures provide a more direct assessment of neuromuscular function. In contrast, the measure of EIM, in the setting of motor neuron loss, is most likely indirectly reflecting atrophy of muscle fibers related to denervation(Sekine et al., 2015). We suggest that in larger clinical trials, especially those that include infants and children, EIM may be a more feasible and reliable measure for a number of reasons including no need for painful electrical stimulation which can limit standard electrophysiology testing in infants and children. Yet, our studies would not argue that EIM and electrophysiology should be employed in a mutually exclusive manner, and it is likely that these measures will be complementary to each other. EIM provides the ability to easily check numerous muscles, including proximal limb, trunk and facial muscles. Yet, electrophysiological measures of CMAP and MUNE offer more direct insight into the functional status of the neuromuscular system. In the current studies, MUNE shows increased sensitivity in identifying milder functional deficits. Thus, MUNE may be more relevant in studies investigating milder forms of SMA.

EIM and electrophysiological techniques, analogous to the ones presented, here have been utilized in both a recently completed natural history SMA study and an ongoing phase 1 gene therapy study in infants with SMA type 1. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01736553 and NCT02122952). The findings of these preclinical studies predict that measures of CMAP, MUNE, and EIM will respond to SMN therapies in infants with SMA provided that therapy is initiated prior to fulminant loss of neuromuscular function. The results of the aforementioned clinical studies, when available, combined with our preclinical results and future clinical studies targeting early symptomatic or presymptomatic infants, will help guide the use of the most effective and relevant biomarkers for future treatment trials in SMA.

Highlights.

Effect of timing of SMN restoration in a spinal muscular atrophy mouse model.

Early SMN therapy demonstrates the largest impact on motor unit deficits.

Electrical impedance myography was comparable to electrophysiological measures.

Electrical impedance myography a non-invasive technique responded to SMN therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (R01NS038650 to A.H.M.B., R01HD060586 to A.H.M.B.), (R01NS055099 to SBR), and (5K12HD001097-17 to W.D.A); and the OSU Cade & Katelyn fund for SMA research, the Marshall Heritage Foundation, and the SMA Foundation.

Abbreviations

- SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy

- EIM

Electrical impedance myography

- ASO

Antisense oligonucleotide

- CMAP

Compound muscle action potential

- MUNE

Motor unit number estimation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahad M, Rutkove SB. Correlation between muscle electrical impedance data and standard neurophysiologic parameters after experimental neurogenic injury. Physiol Meas. 2010;31:1437–1448. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/31/11/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahad MA, et al. Electrical characteristics of rat skeletal muscle in immaturity, adulthood and after sciatic nerve injury, and their relation to muscle fiber size. Physiol Meas. 2009;30:1415–1427. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/30/12/009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahad MA, Rutkove SB. Electrical impedance myography at 50kHz in the rat: technique, reproducibility, and the effects of sciatic injury and recovery. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:1534–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo A, et al. Vascular perfusion abnormalities in infants with spinal muscular atrophy. J Pediatr. 2009;155:292–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SK, Wier CG, Kissel JT,Burghes AH, Kolb SJ. Electrophysiological motor unit number estimation (MUNE) measuring compound muscle action potential (CMAP) in mouse hindlimb muscles. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2015 doi: 10.3791/52899. Accepted 2015. Journal of Visualized Experimentation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WD, Burghes AH. Spinal muscular atrophy: The development and implementation of potential treatments. Ann Neurol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ana.23995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WD, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy: diagnosis and management in a new therapeutic era. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51:157–167. doi: 10.1002/mus.24497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WD, et al. Electrophysiological Biomarkers in Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Preclinical Proof of Concept. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 2014;1:34–44. doi: 10.1002/acn3.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin T, et al. Wound healing response is a major contributor to the severity of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the ear model of infection. Parasite Immunol. 2007;29:501–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2007.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan AK, et al. Early heart failure in the SMNDelta7 model of spinal muscular atrophy and correction by postnatal scAAV9-SMN delivery. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3895–3905. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal F, Olsen PZ. Electromyography and Muscle Biopsy in Infantile Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Brain. 1970;93:15–30. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghes AH, Beattie CE. Spinal muscular atrophy: why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butchbach ME, et al. Abnormal motor phenotype in the SMNDelta7 mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiology of Disease. 2007;27:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distefano G, et al. [Heart involvement in progressive spinal muscular atrophy. A review of the literature and case histories in childhood] Pediatr Med Chir. 1994;16:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez E, et al. Intravenous scAAV9 delivery of a codon-optimized SMN1 sequence rescues SMA mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:681–693. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duque SI, et al. A large animal model of spinal muscular atrophy and correction of phenotype. Ann Neurol. 2015;77:399–414. doi: 10.1002/ana.24332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg RS. Comprehensive Physiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. Impedance Measurement of the Electrical Structure of Skeletal Muscle. [Google Scholar]

- Elso CM, et al. Leishmaniasis host response loci (lmr1–3) modify disease severity through a Th1/Th2-independent pathway. Genes Immun. 2004;5:93–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel RS. Electrophysiological and motor function scale association in a pre-symptomatic infant with spinal muscular atrophy type I. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2013;23:112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel RS, et al. Candidate Proteins, Metabolites and Transcripts in the Biomarkers for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (BforSMA) Clinical Study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel RS, et al. Observational study of spinal muscular atrophy type I and implications for clinical trials. Neurology. 2014;83:810–817. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, et al. Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:271–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Grimnes S, Martinsen ØG. Chapter 11 - History of Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity. In: Martinsen SGG, editor. Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity Basics. Third. Oxford: Academic Press; 2015. pp. 495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Harding BN, et al. Spectrum of neuropathophysiology in spinal muscular atrophy type I. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:15–24. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I, Karwanska A. Electromyographic findings in different forms of infantile and juvenile proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:37–46. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh-Li HM, et al. A mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;24:66–70. doi: 10.1038/71709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang PB, et al. The motor neuron response to SMN1 deficiency in spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49:636–644. doi: 10.1002/mus.23967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, et al. Prospective cohort study of spinal muscular atrophy types 2 and 3. Neurology. 2012;79:1889–1897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318271f7e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb SJ, KJ T. Spinal muscular atrophy: A timely review. Archives of Neurology. 2011;68:979–984. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek WG, et al. Development and evaluation of an impedance cardiac output system. Aerosp Med. 1966;37:1208–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le TT, et al. SMNΔ7, the major product of the centromeric survival motor neuron (SMN2) gene, extends survival in mice with spinal muscular atrophy and associates with full-length SMN. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14:845–857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewelt A, et al. Compound muscle action potential and motor function in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle & Nerve. 2010;42:703–708. doi: 10.1002/mus.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. A comparison of three electrophysiological methods for the assessment of disease status in a mild spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. PLoS One. 2014a;9:e111428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. Electrical impedance myography for the in vivo and ex vivo assessment of muscular dystrophy (mdx) mouse muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2014d;49:829–835. doi: 10.1002/mus.24086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. Electrical impedance alterations in the rat hind limb with unloading. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013;13:37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. A Technique for Performing Electrical Impedance Myography in the Mouse Hind Limb: Data in Normal and ALS SOD1 G93A Animals. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling KK, et al. Severe neuromuscular denervation of clinically relevant muscles in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:185–195. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lungu C, et al. Quantifying muscle asymmetries in cervical dystonia with electrical impedance: a preliminary assessment. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:1027–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComas AJ, et al. Electrophysiological estimation of the number of motor units within a human muscle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34:121–131. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.34.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern VL, et al. SMN expression is required in motor neurons to rescue electrophysiological deficits in the SMNDelta7 mouse model of SMA. Hum Mol Genet. 2015 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naryshkin NA, et al. Motor neuron disease. SMN2 splicing modifiers improve motor function and longevity in mice with spinal muscular atrophy. Science. 2014;345:688–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1250127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH. NIH Consensus statement. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in body composition measurement. National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Conference Statement. December 12–14, 1994. Nutrition. 1996;12:749–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacino J, et al. SMN2 splice modulators enhance U1-pre-mRNA association and rescue SMA mice. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passini MA, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides delivered to the mouse CNS ameliorate symptoms of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:72ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillen S, et al. Assessing spinal muscular atrophy with quantitative ultrasound. Neurology. 2011;76:933. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182068eed. author reply 933–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porensky PN, et al. A single administration of morpholino antisense oligomer rescues spinal muscular atrophy in mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1625–1638. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poruk KE, et al. Observational study of caloric and nutrient intake, bone density, and body composition in infants and children with spinal muscular atrophy type I. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012;22:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renusch SR, et al. Spinal Muscular Atrophy Biomarker Measurements from Blood Samples in a Clinical Trial of Valproic Acid in Ambulatory Adults. Vol. 2. IOS Press; 2015. pp. 119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins KL, et al. Defining the therapeutic window in a severe animal model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4559–4568. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DF, et al. The genetic component in child mortality. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:33–38. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnik-Schoneborn S, et al. Digital necroses and vascular thrombosis in severe spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:144–147. doi: 10.1002/mus.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkove SB. Electrical impedance myography: Background, current state, and future directions. Muscle & Nerve. 2009;40:936–946. doi: 10.1002/mus.21362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkove SB, et al. Electrical impedance myography as a biomarker to assess ALS progression. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012a;13:439–445. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2012.688837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkove SB, et al. Cross-sectional evaluation of electrical impedance myography and quantitative ultrasound for the assessment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in a clinical trial setting. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkove SB, et al. Electrical impedance myography in spinal muscular atrophy: A longitudinal study. Muscle & Nerve. 2012b;45:642–647. doi: 10.1002/mus.23233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkove SB, et al. Characterizing spinal muscular atrophy with electrical impedance myography. Muscle & Nerve. 2010;42:915–921. doi: 10.1002/mus.21784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkove SB, et al. Electrical impedance myography to assess outcome in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical trials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:2413–2418. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez B, et al. Novel approach of processing electrical bioimpedance data using differential impedance analysis. Med Eng Phys. 2013;35:1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine K, et al. Numerical calculations for effects of structure of skeletal muscle on frequency-dependence of its electrical admittance and impedance. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2015;48:255401. [Google Scholar]

- Shababi M, et al. Partial restoration of cardio-vascular defects in a rescued severe model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1074–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shababi M, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy: a motor neuron disorder or a multi-organ disease? J Anat. 2014;224:15–28. doi: 10.1111/joa.12083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shefner JM. Motor unit number estimation in human neurological diseases and animal models. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001;112:955–964. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava T, et al. Machine learning algorithms to classify spinal muscular atrophy subtypes. Neurology. 2012;79:358–364. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182604395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung M, et al. The effect of subcutaneous fat on electrical impedance myography when using a handheld electrode array: The case for measuring reactance. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2013;124:400– 404. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda KJ, et al. Natural history of denervation in SMA: Relation to age, SMN2 copy number, and function. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57:704–712. doi: 10.1002/ana.20473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarulli AW, et al. Electrical impedance myography in the assessment of disuse atrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1806–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valori CF, et al. Systemic Delivery of scAAV9 Expressing SMN Prolongs Survival in a Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2:35ra42. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmott AD, et al. Fibrillation potential onset in peripheral nerve injury. Muscle & Nerve. 2012;46:332–340. doi: 10.1002/mus.23310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JS, et al. Assessment OF aged mdx mice by electrical impedance myography and magnetic resonance imaging. Muscle Nerve. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mus.24573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]