Abstract

Purpose

Civilians living amid conflict are at high-risk of burns. However, the epidemiology of burns among this vulnerable group is poorly understood, yet vital for health policy and relief planning. To address this gap, we aimed to determine the death and disability, healthcare needs and household financial consequences of burns in post-invasion Baghdad.

Methods

A two-stage, cluster randomized, community-based household survey was performed in May of 2014 to determine the civilian burden of injury from 2003 to 2014 in Baghdad. In addition to questions about cause of household member death, households were interviewed regarding burn specifics, healthcare required, disability, relationship to conflict and resultant financial hardship.

Results

Nine-hundred households, totaling 5,148 individuals, were interviewed. There were 55 burns, which were 10% of all injuries reported. There were an estimated 2,340 serious burn injures (39 per 100,000 persons) in Baghdad in 2003. The frequency of serious burn injuries generally increased post-invasion to 8,780 burns in 2013 (117 per 100,000 persons). Eight burns (15%) were the direct result of conflict. Individuals aged over 45 years had more than twice the odds of burn injury than children aged less than 13 years (aOR 2.42; 95%CI 1.08 – 5.44). Nineteen burns (35%) involved ≥20% body surface area. Death (16% of burn injuries), disability (40%), household financial hardship (48%) and food insecurity (50%) were common after burn injury.

Conclusion

Civilian burn injury in Baghdad is epidemic, increasing in frequency and associated with household financial hardship. Challenges of healthcare provision during prolonged conflict were evidenced by a high mortality rate and likelihood of disability after burn injury. Ongoing conflict will directly and indirectly generate more burns, which mandates planning for burn prevention and care within local capacity development initiatives, as well as humanitarian assistance.

Keywords: burn, electrical injury, Iraq, war, epidemiology, global surgery

Introduction

Trauma and violence continue to be under-appreciated public health problems, accounting for more than 6 million deaths and 275 million disability-adjusted life years globally.[1] Civilians living amid conflict carry a disproportionate burden of injury.[2] Although intentional harm of civilians during war violates human rights and humanitarian law, civilians are injured in modern-day conflicts because of indiscriminate combat tactics and weapons used near them.[3–5] Subsequently, civilians may account for up to 80% of killed or wounded during war.[3, 5, 6] Moreover, indirect wartime civilian injury may be even greater due to the effect of conflict on daily living conditions, safe behavior, and health systems.[2, 7–9]

Since the United States-led coalition invasion in 2003, persons living in Iraq have had one of the highest risks of dying violently in the world.[4] Estimates of excess deaths from violence range between 100,000 and 800,000 persons in post-invasion Iraq with Baghdad at the epicenter.[10–13] Despite coalition withdrawal from the city center in 2011, dramatic acts of violence continue to threaten civilians daily.[14] Further, displaced persons that have taken residence in Baghdad have overwhelmed the fragile healthcare system.[15] Together, civilian injury and its sequelae likely represent an urgent public health problem.

The risk of burn injury is ubiquitous during conflict among both combatants and civilians.[16] Most wartime burns result from explosive devices, resulting breakdown of infrastructure and poor fire prevention practices.[2, 3, 17] In 2009, burns were responsible for 9% of all injuries in Baghdad;[2] death from explosions and electrocutions were common.[2] Even in peacetime, burns can be difficult to manage; they require brisk resuscitation and an adept multidisciplinary team to avert death and disability.[18] During insecurity, these services are in jeopardy or non-existent. Consequently, mortality and morbidity is common among civilians burned during conflict.[2, 17]

Despite a growing need to prevent and treat injury among civilians living amid conflict, few community-based studies characterize injury and burn epidemiology during conflict.[2] In addition, none have described both mortality and morbidity over time.[2, 6] To address this gap, we conducted a two-stage, cluster randomized, community-based survey of injuries and disabilities in Baghdad in 2014, just before the security situation worsened. We aimed to understand the epidemiology of civilian conflict- and non-conflict-related burn injuries in post-invasion Baghdad. By doing so, a better estimate of the cumulative effect of insecurity on civilian burn injury could be determined, which might inform prevention initiatives, health policy and relief planning.

Methods

Study design

A team of international and Iraqi public health and trauma experts with experience from previous two-stage cluster study designs in Iraq, Rwanda and Sierra Leone developed the survey strategy.[11, 19, 20] A survey instrument was adapted from the World Health Organization’s community injury survey guidelines and the Surgeons OverSeas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS).[19–21] The instrument was translated into Arabic, back translated to assure accuracy and piloted for utility and validity. The final version was designated the Surgeons OverSeas Injury Survey (SOSINJ).

A two-stage randomized 30 cluster by 30 households sample was performed. The total sample size was estimated to be 3,650 individuals using n=Z2p(1−p)/L2, where Z is confidence interval (95%−Z is 1.96), p was the anticipated prevalence of the injury (5%), L was the accepted range around the estimated prevalence of injury (1%), and the design effect was 2. Therefore, our sample of 5,148 individuals was more than adequate to achieve our desired precision (1%).

Baghdad was divided into 14 administrative districts and sectors and 30 random clusters were chosen using Google Earth™. Clusters were delineated based on the 2011 population estimates for administrative units in Baghdad. Data were obtained from the Iraqi Central Organization for Statistics and Information Technology and Ministry of Health.[22] Five clusters were randomly replaced due to security concerns or being located proximate sensitive military facilities a priori.

Data collection

The starting household and a backup starting household were selected using satellite imagery and grids in Google Earth™.[23] If teams deemed the starting household unsafe they proceeded to the backup starting household. After the starting household, every other household was interviewed until 30 households were completed. A household was defined as a group of persons living together in a dwelling with a separate outer door and a separate kitchen. Most clusters had no household refusal. However, five clusters had a single refusal each.

Two teams of four trained Iraqi physicians worked with a supervisor and sampled households in May of 2014. Heads of household were identified and explained the survey procedure. After obtaining verbal informed consent, heads of the household were interviewed with regard to household demographics. Questions on injuries (including burns), mechanism, relation to conflict, care required, disabilities (e.g. ability to care for self, climb stairs, walk or suffering of pain, stigma or anxiety/depression), financial hardship, suspected responsible party for intentional injuries and others were asked. Subsequently, all available household members were interviewed. The head of household provided information about injuries and disabilities for household members who were unable to answer questions (e.g. children, head injured) or not present.

Data management and analysis

Data were collected on paper forms and doubly entered into a database. Discrepancies were immediately clarified with collection teams. We described demographic factors and burn injuries with counts and relative proportions. Simple bivariate logistic regression was used to model the effect of each covariate on having suffered a burn injury after 2002. Odds ratios, adjusted for gender and age (i.e. variables with a priori evidence of strong association with burn injury), were calculated by using a three-level mixed-effects logit link function to control for intra-class correlation among clusters and within households. Bidirectional stepwise model construction was performed using Alkaike’s information criteria (AIC) and the Wald test to identify the model with the best fit and prediction ability. The p-value for gender and age as the sole covariates using the Wald test was 0.07 and 0.01, respectively. With the addition of other covariates, the p-values for gender and age increased above 0.24; similarly, the models’ AICs increased. The p-values using the Wald test for other covariates, both with and without gender and age in the model, were greater than 0.31. Thus, the a priori model demonstrated best fit. The final model was:[24, 25]

Using national census data from 1997, 2003 and 2011 performed by the Iraqi Central Organization for Statistics and Information Technology, incidence rates were calculated.[22] For years between censuses, the population of Baghdad was estimated using second-degree parabolic extrapolation.[26] All analyses were performed using Stata® (College Station, TX, USA).

To minimize reporting recall biased results, incidence rates were calculated using only serious burn injuries. Serious burn injuries were defined as those resulting in death, hospitalization or surgery or more than one month of selected disabilities (i.e. inability to care for self or walk outside of the home, suffering chronic pain or being unable to work due to anxiety or depression after injury). Further, a sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the proportion of reported burn injuries that resulted in death or ongoing disability. Non-fatal burn injuries with ongoing disability that occurred 2014 were excluded in the sensitivity analysis given their potentially short duration. By comparing all reported burn injuries and serious burn injuries per year, conclusions can be drawn about the potential for recall bias.

Ethics and funding

Al Mustansiriya University and Baghdad Provincial Council approved the study. Approvals for secondary analysis of the de-identified database were obtained through Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the University of Washington institutional review boards. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each head of household prior to interview and payment was not given to participants. No names or other identifying information were collected. Funding for logistics in Baghdad was provided by the United States based non-governmental organization, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS).

Results

Serious burn injury incidence rate

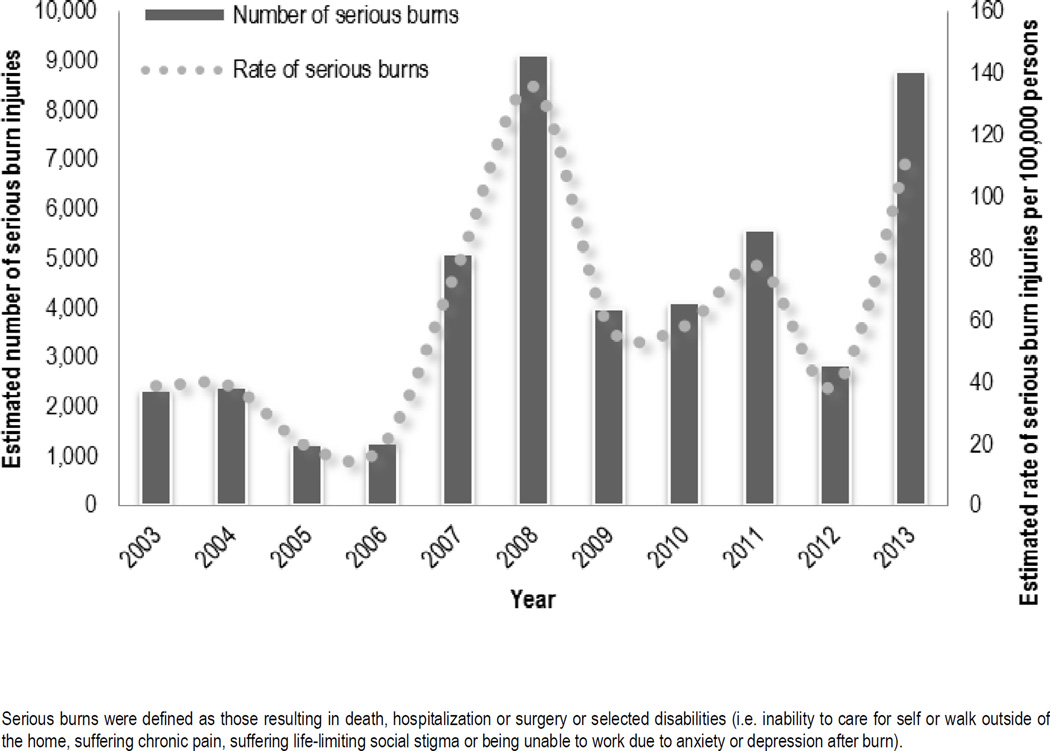

Thirty randomly selected households from each of 30 clusters were surveyed, totaling 900 households and 5,148 individuals. There were 55 burn injuries, which were 10% of all injuries reported. Forty-two of the burn injuries were serious (i.e. death, hospitalized, disabled for more than a month or required surgery; 76%). In 2003, there were an estimated 2,340 serious burn injuries (39 per 100,000 persons) in Baghdad. The incidence of serious burns generally increased post-invasion and was around 8,780 in 2013 (117 per 100,000 persons) (Figure 1). When the definition of serious burn injury was restricted to only death and ongoing disability there were an estimated 1,170 serious burn injuries in 2003 (19 per 100,000 persons) and 5,854 in 2013 (78 per 100,000) (Supplementary Material).

Figure 1. Estimated number and rate of serious burn injuries in Baghdad, Iraq from 2003 – 2014.

Serious burns were defined as those resulting in death, hospitalization or surgery or selected disabilities (i.e. inability to care for self or walk outside of the home, suffering chronic pain, suffering life-limiting social stigma or being unable to work due to anxiety or depression after burn).

Burn injury epidemiology

Burn injuries were more often reported by men (34 burn injuries; 62%) than women (21; 39%; p=0.08); however, there was not evidence for a difference for burn injury between sex (Table 1). The likelihood of burn injury among adults aged at least 45 years was around twice that of children 12 years old or younger (aOR 2.42; 95%CI 1.08 – 5.44). Burn injury was more likely to occur while at home (aOR 2.20; 95%CI 1.11 – 4.36) compared to being in public. There was weak evidence for greater odds of suffering a burn injury in a factory or industrial setting (aOR 2.69; 95%CI 0.90 – 7.84) compared to being in public. No other significant associations between other demographic characteristics (e.g. education, marital status, occupation) and odds of burn injury were found.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of household members and burn victims in Baghdad, Iraq from 2003 – 2014.

| Total | Burn injuries | Odds Ratios | Adj. Odds Ratios* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=5,148 | n | (%) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Injured | 553 | 55 | (10) | - | - |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 2,579 | 34 | (1) | Referent | Referent |

| Female | 2,569 | 21 | (1) | 0.62 (0.36 – 1.07) | 0.60 (0.35 – 1.05) |

| Age | |||||

| ≤12 years | 1,556 | 11 | (1) | Referent | Referent |

| 13 – 24 years | 1,204 | 10 | (1) | 1.18 (0.50 – 2.78) | 1.22 (0.51 – 2.92) |

| 25 – 45 years | 1,413 | 19 | (1) | 1.91 (0.91 – 4.04) | 2.01 (0.94 – 4.23) |

| ≥45 years | 975 | 15 | (2) | 2.20 (1.00 – 4.80) | 2.42 (1.08 – 5.44) |

| Education among injured | |||||

| None | 102 | 9 | (9) | Referent | Referent |

| Any Primary | 261 | 31 | (2) | 1.40 (0.64 – 3.04) | 1.59 (0.69 – 3.68) |

| Completed at least secondary | 190 | 15 | (8) | 0.89 (0.37 – 2.10) | 1.08 (0.41 – 2.83) |

| Marital status of injured | |||||

| Never married | 238 | 25 | (1) | Referent | Referent |

| Married | 292 | 27 | (9) | 0.87 (0.49 – 1.54) | 1.10 (0.51 – 2.38) |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 23 | 3 | (3) | 1.28 (0.36 – 4.61) | 1.69 (0.40 – 7.13) |

| Occupation of injured | |||||

| Student | 106 | 11 | (1) | Referent | Referent |

| Employed | 157 | 14 | (9) | 0.85 (0.37 – 1.94) | 1.15 (0.42 – 3.20) |

| Farmer | 97 | 16 | (7) | 1.71 (0.75 – 3.89) | 2.54 (0.91 – 7.07) |

| Unemployed, retired, homemaker | 139 | 8 | (6) | 0.53 (0.20 – 1.36) | 0.62 (0.20 – 1.94) |

| Other | 54 | 6 | (1) | 1.08 (0.38 – 3.10) | 0.90 (0.28 – 2.86) |

| Unintentional injury at work | |||||

| No | 240 | 31 | (3) | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 61 | 8 | (3) | 0.98 (0.43 – 2.26) | 1.13 (0.46 – 2.77) |

| Location of injury | |||||

| Public | 270 | 20 | (7) | Referent | Referent |

| Farm | 2 | 0 | - | - | |

| House | 186 | 27 | (5) | 2.12 (1.15 – 3.91) | 2.20 (1.11 – 4.36) |

| Office or school | 31 | 0 | - | - | |

| Factory, industrial shop | 29 | 5 | (7) | 2.60 (0.90 – 7.56) | 2.65 (0.90 – 7.84) |

| Automobile | 22 | 2 | (9) | 1.25 (0.27 – 5.73) | 1.23 (0.26 – 5.70) |

| Airplane | 2 | 1 | - | - | |

| Other | 11 | 0 | - | - | |

Model adjusted for gender and age.

Adj. – adjusted for age, sex and education level

Eight burn injuries (15%) were the direct result of conflict. Of these, 6 burns were reported as perpetrated by sectarian militias and 2 burns by criminals. The causes of the remaining 47 burns not directly related to conflict varied. However, fire or scald burns (22 burns; 47% of unintentional burn injuries) and electrical injuries (14; 30%) were most common (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of conflict- and non-conflict-related burn injuries in Baghdad, Iraq from 2003 – 2014 (N=55).

| Non-conflict | Conflict | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Cause | ||||

| Fire, hot liquid, other | 22 | (47) | 4 | (50) |

| Electrical injury | 14 | (30) | 0 | |

| Contact | 3 | (6) | 0 | |

| Explosion | 2 | (4) | 0 | |

| Assault | 1 | (2) | 0 | |

| Explosive device | 0 | 4 | (50) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (2) | 0 | |

| Reported responsible party | ||||

| Criminals | - | 2 | (25) | |

| Militia or sectarian group | - | 6 | (75) | |

| Iraqi or coalition forces | - | 0 | ||

| Unknown | - | 0 | ||

| Total | 47 | (100) | 8 | (100) |

Burn injuries, death and disability

Nineteen burns (35%) involved at least 20% of the individual’s body surface area (TBSA) (Table 3). The extent of 13 burns was not known (24% of burn injuries). Forty-six respondents who sustained burn injury (85%) sought care at a hospital or clinic, 20 (37%) required hospitalization and 22 (41%) required surgical care. Care required for 18 household members who suffered burn injury (33%) was unknown.

Table 3.

Extent of burns and care required for burn injury in Baghdad, Iraq from 2003 – 2014.

| Burn injuries (N=55) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| TBSA | ||

| <20% | 23 | (43) |

| ≥20% | 19 | (35) |

| Unknown | 13 | (24) |

| Initial site of care | ||

| Hospital | 21 | (41) |

| Public clinic | 3 | (6) |

| Work or private clinic | 22 | (43) |

| Nurse | 5 | (10) |

| No care sought | 0 | |

| Surgical care | ||

| Procedure(s) with anesthesia | 7 | (13) |

| Procedure(s) without anesthesia | 15 | (28) |

| No procedure requires | 14 | (26) |

| Unknown | 18 | (33) |

| Hospitalization | ||

| Not hospitalized | 17 | (32) |

| <2 weeks | 13 | (24) |

| ≥2 weeks | 7 | (13) |

| Unknown | 17 | (31) |

TBSA – total body surface area

There were 9 deaths (16% of burn injuries). Most deaths were in those with ≥20% TBSA (6 burn injuries; 67% of burn deaths) or electrical injury (2; 22%). Twenty-two respondents who sustained burn injury (40%) had some form of disability. Inability to independently perform activities of daily living (ADLs; 18 respondents; 45% of disabilities) or walk (14; 35%) was common after burn injury. In addition, suffering chronic pain (12 respondents; 30%), social stigma (29; 73%) and anxiety or stress response or emotional changes that limit pre-injury activities (15; 38%) were frequently reported (Table 4).

Table 4.

Death and disability after burn injury in Baghdad, Iraq from 2003 – 2014.

| Burn injuries (n=55) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Death | 9 | (16) |

| Electrical injury | 2 | (22) |

| <20% TBSA | 0 | |

| ≥20% TBSA | 6 | (67) |

| Unknown | 1 | (11) |

| Disability | 22 | (40) |

| Needs assistance with self-care | 18 | (45) |

| Unable to walk out of house | 14 | (35) |

| Deafness | 7 | (18) |

| Chronic pain | 12 | (30) |

| Suffers social stigma | 29 | (73) |

| Anxiety, emotional changes | 12 | (30) |

| Emotional changes preventing activity | 3 | (8) |

TBSA – total body surface area

Household consequences of burn injury

Burn injury often impacted the household. Nearly half of affected households (26 households; 48% of households that suffered a burn injury) witnessed a decline in household income and/or suffered food insecurity (27; 50%) (Table 3). Eighteen families (33%) had to borrow money to pay medical bills or sustain daily life. Nearly half of affected households that borrowed money (9 households; 48%) had to borrow 25 to ≥100% of the average Iraqi household income to recover financial losses after burn injury. In Iraq, per capita income US$ 4,272 per year.[27, 28]

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe the morbidity and mortality associated with civilian burn injuries in post-invasion Baghdad to provide better estimates of the effect of insecurity on civilian burn injury. By doing so, we could generate information useful for health system and relief planning. Civilian burn injury in Baghdad is epidemic and has generally increased since 2003. The majority of burn injuries were not a direct result of conflict. The typical epidemiological pattern of burn injury in LMICs was not seen in Baghdad. Instead, there was a high proportion of severe burns, electrical injuries and burn injuries in adults. Lastly, challenges of healthcare provision during prolonged conflict were evidenced by a higher than expected proportion of deaths and likelihood of disability after burn injury. These results suggest that burn injuries are an important public health problem in Baghdad, potentially due to the effect of insecurity on society.

Burn injury is ubiquitous during conflict.[3] Previous studies of civilian injuries in LMICs disrupted by conflict reported that burns were responsible for 4 – 10% of all injuries.[3, 29, 30] Conversely, community-based surveys in Nepal and Sierra Leone during peacetime found that 2% and 4% of respondents had suffered a burn injury, respectively.[24, 31] Wartime studies from Croatia, Bosnia, Lebanon and Afghanistan also described burns being common in all age groups, in contrast to usual high-risk groups in peacetime, namely women and children.[29, 30, 32–35] These data reinforce findings from insecure countries by reporting 10% of all injuries were burns. Additionally, there was an atypical distribution of burn injury among age-groups (i.e. more frequent in adults aged at least 45 years) and a trend toward a greater likelihood of burns in men compared to women. The unusual distribution of burn injuries among civilians affected by conflict compared to those in peacetime should be considered when developing prevention initiatives, which have typically focused on women and children in LMICs.

In addition to direct casualties, conflict disrupts structural safety, prevention programs and usual precautionary behavior.[2, 9, 15] Resultantly, all members of society become more susceptible to injury and its consequences.[2] As conflict lengthens, these important structures continue to degrade.[2, 15] Burn and electrical injuries were increasingly frequent post-invasion, which may have been the result of the toll conflict has taken on Baghdad’s safe infrastructure and degeneration of usual safe behavior.[9, 35] Given this additional background risk of burn injury, support of Iraqi health systems should consider promoting household and infrastructure fire safety, in addition to strengthening burn care.

LMICs, though usually able to provide basic resuscitation after burn injury, are often unable to care for serious injury, perform grafting, manage burn complications or provide mental health, rehabilitation or reintegration services.[36] War directly creates humanitarian medical needs by generating casualties and disrupting local healthcare provision.[2, 37] Complicating the increased burden, fragile and fragmented healthcare systems in LMICs have inadequate access to pre-hospital care, necessary resources, specialty services, and rehabilitation.[38] Therefore, the addition of conflict makes the burn injured in LMICs at even higher risk of death and disability.[3] There are around 15 functional general and teaching hospitals in Baghdad that have dedicated burn units. While these facilities are accessible by most persons, they run at or above capacity, are not designed around the ‘burn center’ concept, and have suffered from the effects of prolonged conflict.[39–41] In addition, less than half of patients in need have access to these hospitals, given an inadequate number of facilities and an uneven distribution of public hospitals.[42] Thus, 16% of those burned in Baghdad died, which is higher than previous studies that reported a 5 to 10% mortality among civilians burned during wartime elsewhere, as well as in LMICs not affected by crisis.[43–47] Significant disability was analogously common in Baghdad after burn injury (40%); the proportion of burn injuries that resulted in disability documented by a similar community-based survey from Nepal after the civil war there was only 13%.[31] These results suggest that burn prevention initiatives and the Iraqi healthcare system are in need of significant assistance to reduce the death and disability from burn injury until insecurity recedes and reconstruction successful.

The financial costs of caring for burn survivors and lost income from the previously working injured can be crippling to a family. This study found a significant proportion of households not only borrowed large sums of money, but also subsequently suffered food insecurity. After the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, children of family members who were injured had more than twice the odds of suffering from food insecurity than children without an injured family member, independent of household damage.[48] Households that received small remittances after the earthquake were less likely to face food insecurity. Given the frequency of burns in Baghdad and the impact of injury on household food security, relief and recovery efforts should also consider the broader financial implications of burn injury on affected households.

This study is a large, community-based assessment of burns in post-invasion Baghdad. However, there are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The incidence rates of burn injury reported are bare minimum estimates for several reasons. First, five insecure clusters were replaced with more secure ones for the safety of study members. These areas may have had a higher burn injury rates compared to clusters with greater security. However, these clusters were replaced a priori and at random to minimize potential selection bias. Second, individuals who reported multiple injuries, possibly including burn injury, were not included in the burn injury group since the injury pattern was not further described by the data. As described above, conflict-related injuries from explosions are often associated with burn injury. Given that respondents reported 41 explosion injuries, these figures likely underestimate burn injury in Baghdad. Third, there has been significant internal displacement and emigration for asylum and to seek medical care in the last decade in Iraq. Possibly, those greatest affected or injured by the conflict have fled, reducing the number of families that reported burn injury or death. Lastly, with only 55 burns we were unable to show evidence for associations with several demographic and circumstantial factors. However, important associations may exist.

Surveys depend on recall of respondents. Given the ten-year recall period used in this study, one would anticipate memory decay. Burn injury was reported as being more common now than immediately after the invasion. In addition, respondents more often reported minor burn injuries in recent years compared to early in the target period, suggesting recall bias. To minimize the effect of recall bias on these results, incidence rates were calculated using only serious burns that are less likely to be forgotten. Further, results from the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the rate of serious burn injuries and burn injuries that resulted in death or ongoing disability also increased across the decade (supplementary material). Therefore, recall bias did not account for this trend alone.

SOSINJ was developed to characterize the epidemiology of a number of injuries (i.e. SOSINJ was not designed specially for burns). Therefore, information on inhalation injury and other burn-specific data were not collected, limiting the analysis. It is often difficult to ascertain the etiology of the injury, its preventability and who is responsible, particularly during crisis. Therefore, more detailed ascription of a burn to its cause and the conflict was not possible. Despite these limitations, these results allow important conclusions to be drawn about the epidemiology and burden of civilian burn injuries in post-invasion Baghdad and the potential implication of prolonged insecurity on burn epidemiology more broadly.

Conclusion

Civilian burn injury in post-invasion Baghdad is epidemic, increasing in frequency and often severe. These data support findings that reported burn injuries were more common among older adults and men during wartime, compared to women and children during peacetime. Challenges of healthcare provision during prolonged conflict were evidenced by a greater than expected mortality rate and high likelihood of disability after burn injury. Lost or diverted income after burn injury often strained affected families, frequently resulting in food insecurity. For these reasons, burn prevention, local healthcare development and humanitarian assistance are urgently needed to reduce this neglected disease burden in Iraq. In addition, extending support to the households of burn-injured patients may avert indirect death and disability related to food-insecurity. Such benefits on vulnerable family members, such as women, elders and children, may be significant. These data demonstrate that LMICs strained by protracted insecurity should consider defining the burden of burn injury in their population to better plan prevention initiatives, health policy and relief efforts.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

Household financial consequences after burn injury in Baghdad, Iraq from 2003 – 2014.

| Burn injuries (N=55) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Financial consequences | ||

| Decline in household income | 26 | (48) |

| Decline in household food availability | 27 | (50) |

| Borrowed money: USD | 18 | (33) |

| <250 | 3 | (15) |

| 250 – 999 | 7 | (37) |

| 1,000 – 4,999 | 7 | (37) |

| ≥5,000 | 2 | (11) |

USD - United States dollars

Highlights.

Burns increased post-invasion from 39 per 100,000 persons in 2003 to 117 in 2013

Unlike peacetime epidemiology, burns were more common in men and older adults

Death (16%), disability (40%), and food insecurity (50%) were common after burn injury

Acknowledgments

We thank the dedicated supervisors and enumerators who for their contribution to understanding injury in Baghdad and helping to plan a response. Funding for logistics in Baghdad was provided by the United States based non-governmental organization, Surgeons OverSeas. Data analysis and manuscript preparation was done with support from the United States National Institutes of Health and Fogarty International Center through the Northern Pacific Global Health Research Fellows Training Consortium under grant R25TW009345. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no other disclosures.

Author contributions

The study was designed by RL, SAS, GB, AH and ALK. Data collection, or supervision thereof, was done by RL, SAS, GB, and ALK. The data were analyzed and interpreted by BTS, MC, AH and LG. Manuscript preparation was done by BTS, MC, AH, LG and ALK. All authors contributed critically and significantly to drafting a final manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Barclay T Stewart, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Riyadh Lafta, Department of Community Medicine, Al Munstansiriya University, Baghdad, Iraq; Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Sahar A Esa Al Shatari, Human Resources Development and Training Center, Iraq Ministry of Health, Baghdad, Iraq.

Megan Cherewick, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Gilbert Burnham, Department of International Health, Center for Refugee and Disaster Response, Johns Hopkins, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Amy Hagopian, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Health Services, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Lindsay P Galway, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada.

Adam L Kushner, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA; Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; Department of Surgery, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Data Visualizations. Global Burden of Disease Cause Patterns. Seattle, WA: Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson RI, Hung YW, Shanovich P, Hasoon T, Evans G. Injury burden during an insurgency: the untold trauma of infrastructure breakdown in Baghdad, Iraq. The Journal of trauma. 2010;69:1379–1385. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318203190f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atiyeh BS, Gunn SW, Hayek SN. Military and civilian burn injuries during armed conflicts. Annals of burns and fire disasters. 2007;20:203–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicks MH, Dardagan H, Guerrero Serdan G, Bagnall PM, Sloboda JA, Spagat M. Violent deaths of Iraqi civilians, 2003–2008: analysis by perpetrator, weapon, time, and location. PLoS medicine. 2011;8:e1000415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinsley DE, Rosell PA, Rowlands TK, Clasper JC. Penetrating missile injuries during asymmetric warfare in the 2003 Gulf conflict. The British journal of surgery. 2005;92:637–642. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aboutanos MB, Baker SP. Wartime civilian injuries: epidemiology and intervention strategies. The Journal of trauma. 1997;43:719–726. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199710000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toole MJ, Galson S, Brady W. Are war and public health compatible? Lancet. 1993;341:1193–1196. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91013-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. Refugees and displaced persons. War, hunger, and public health. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270:600–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devakumar D, Birch M, Osrin D, Sondorp E, Wells JC. The intergenerational effects of war on the health of children. BMC medicine. 2014;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnham G, Lafta R, Doocy S, Roberts L. Mortality after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: a cross-sectional cluster sample survey. Lancet. 2006;368:1421–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagopian A, Flaxman AD, Takaro TK, Esa Al Shatari SA, Rajaratnam J, Becker S, et al. Mortality in Iraq associated with the 2003–2011 war and occupation: findings from a national cluster sample survey by the university collaborative Iraq Mortality Study. PLoS medicine. 2013;10:e1001533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts L, Lafta R, Garfield R, Khudhairi J, Burnham G. Mortality before and after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: cluster sample survey. Lancet. 2004;364:1857–1864. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iraq Family Health Survey Study G. Alkhuzai AH, Ahmad IJ, Hweel MJ, Ismail TW, Hasan HH, et al. Violence-related mortality in Iraq from 2002 to 2006. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:484–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asssociated_Press. The Independent. London: 2011. US lowers flag to end Iraq war. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Hilfi TK, Lafta R, Burnham G. Health services in Iraq. Lancet. 2013;381:939–948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart B, Trelles M, Dominguez L, Wong E, Fiozounam H, Hassani G, et al. Surgical burn care by Médecins Sans Frontières Operations Center Brussels: 2008–2014. Accepted by Journal of Burn Care and Research. 2014 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000305. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atiyeh BS, Hayek SN. Management of war-related burn injuries: lessons learned from recent ongoing conflicts providing exceptional care in unusual places. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2010;21:1529–1537. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f3ed9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atiyeh B, Masellis A, Conte C. Optimizing burn treatment in developing low- and middle-income countries with limited health care resources (part 1) Annals of burns and fire disasters. 2009;22:121–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart KA, Groen RS, Kamara TB, Farahzad MM, Samai M, Cassidy LD, et al. Traumatic injuries in developing countries: report from a nationwide cross-sectional survey of Sierra Leone. JAMA surgery. 2013;148:463–469. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petroze RT, Joharifard S, Groen RS, Niyonkuru F, Ntaganda E, Kushner AL, et al. Injury, Disability and Access to Care in Rwanda: Results of a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Population Study. World journal of surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World_Health_Organization. Geneva: 2004. Guidelines for Conducting Community Surveys on Injuries and Violence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Central Statistical Organization. General Census. Iraq: Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Planning; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galway L, Bell N, Sae AS, Hagopian A, Burnham G, Flaxman A, et al. A two-stage cluster sampling method using gridded population data, a GIS, Google Earth(TM) imagery in a population-based mortality survey in Iraq. International journal of health geographics. 2012;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong EG, Groen RS, Kamara TB, Stewart KA, Cassidy LD, Samai M, et al. Burns in Sierra Leone: A population-based assessment. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roudsari BS, Shadman M, Ghodsi M. Childhood trauma fatality and resource allocation in injury control programs in a developing country. BMC public health. 2006;6:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United_Nations. Methods requiring three or more previous censuses. Geneva: The United Nations; Estimates derviced by extrapolation of census results. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World_Bank_Group. World Development Indicators. In: Accounts ON, editor. GNI per capita: Atlas method. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.UN_Development_Programme. Country report. Iraq: 2013. Country programme actrion plan: 2011–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vujovic B, Mazlagic D. Epidemiology and surgical management of abdominal war injuries in Sarajevo: State Hospital of Sarajevo experience. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 1994;9:S29–S34. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00041157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pretto EA, Begovic M, Begovic M. Emergency medical services during the siege of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina: a preliminary report. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 1994;9:S39–S45. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00041170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta S, Mahmood U, Gurung S, Shrestha S, Kushner AL, Nwomeh BC, et al. Burns in Nepal: A population based national assessment. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nassoura Z, Hajj H, Dajani O, Jabbour N, Ismail M, Tarazi T, et al. Trauma management in a war zone: the Lebanese war experience. The Journal of trauma. 1991;31:1596–1599. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhatnagar MK, Curtis MJ, Smith GS. Musculoskeletal injuries in the Afghan war. Injury. 1992;23:545–548. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(92)90157-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyder AA, Ghaffar A, Masud TI, Bachani AM, Nasir K. Injury patterns in long-term refugee populations: a survey of Afghan refugees. The Journal of trauma. 2009;66:888–894. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181627614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aenab AM, Singh SK. Environmental Assessment of Infrastructure Projects of Water Sector in Baghdad, Iraq. Journal of Environmental Protection. 2012;3:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta S, Wong E, Mahmood U, Charles AG, Nwomeh BC, Kushner AL. Burn management capacity in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review of 458 hospitals across 14 countries. International journal of surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giannou C, Baldan M. War Surgery: working with limited resources in armed conflict and other situations of violence. Geneva, Switzerland: International Committee of the Red Cross; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.World_Health_Organization. Analysing Disrupted Health Sectors. Geneva: 2008. Analysing Disrupted Health Systems in Countries in Crises. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dyer O. Iraq's hospitals struggle to provide a service. Bmj. 2003;326:899. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7395.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burnham GM, Lafta R, Doocy S. Doctors leaving 12 tertiary hospitals in Iraq, 2004–2007. Social science & medicine. 2009;69:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lafta RK, Al-Nuaimi MA. National perspective on in-hospital emergency units in Iraq. Qatar Med J. 2013;2013:19–27. doi: 10.5339/qmj.2013.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cetorelli V, Shabila NP. Expansion of health facilities in Iraq a decade after the US-led invasion, 2003–2012. Conflict and health. 2014;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf SE, Kauvar DS, Wade CE, Cancio LC, Renz EP, Horvath EE, et al. Comparison between civilian burns and combat burns from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. Annals of surgery. 2006;243:786–792. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000219645.88867.b7. discussion 92–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez R, Murray CK, Hospenthal DR, Cancio LC, Renz EM, Holcomb JB, et al. Causes of mortality by autopsy findings of combat casualties and civilian patients admitted to a burn unit. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;208:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olawoye OA, Iyun AO, Ademola SA, Michael AI, Oluwatosin OM. Demographic characteristics and prognostic indicators of childhood burn in a developing country. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahuja RB, Goswami P. Cost of providing inpatient burn care in a tertiary, teaching, hospital of North India. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2013;39:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashmi M, Kamal R. Management of patients in a dedicated burns intensive care unit (BICU) in a developing country. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2013;39:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hutson RA, Trzcinski E, Kolbe AR. Features of child food insecurity after the 2010 Haiti earthquake: results from longitudinal random survey of households. PloS one. 2014;9:e104497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.