Abstract

Background

Cyberbullying has established links to physical and mental health problems including depression, suicidality, substance use, and somatic symptoms. Quality reporting of cyberbullying prevalence is essential to guide evidence-based policy and prevention priorities. The purpose of this systematic review was to investigate study quality and reported prevalence among cyberbullying research studies conducted in populations of US adolescents of middle and high school age.

Methods

Searches of peer-reviewed literature published through June 2015 for “cyberbullying” and related terms were conducted using PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, and Web of Science. Included manuscripts reported cyberbullying prevalence in general populations of U.S. adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19. Using a review tool based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement, reviewers independently scored study quality on study methods, results reporting, and reported prevalence.

Results

Search results yielded 1,447 manuscripts; 81 manuscripts representing 58 unique studies were identified as meeting inclusion criteria. Quality scores ranged between 12 and 37 total points out of a possible 42 points (M = 26.7, SD = 4.6). Prevalence rates of cyberbullying ranged as follows: perpetration, 1% to 41%; victimization, 3% to 72%; and overlapping perpetration and victimization, 2.3% to 16.7%.

Conclusions

Literature on cyberbullying in US middle and high school aged students is robust in quantity but inconsistent in quality and reported prevalence. Consistent definitions and evidence-based measurement tools are needed.

Keywords: Cyberbullying, Bullying, Systematic review, Internet, Social media, Text messaging, Prevalence, Research, United States

Cyberbullying is an emerging public health concern among adolescents, with established links to physical and mental health problems.1 Youth who experience cyberbullying are more likely to complain of difficulty sleeping, recurrent abdominal pain and frequent headaches.2 They are also more likely to endorse symptoms of anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation compared to non-victimized peers.1,3,4 Cyberbullying differs from ‘traditional’ forms of bullying (i.e., physical, relational, and reputational aggression) due to distinct features of the electronic medium.5 These include a virtually limitless audience, greater potential for anonymity by perpetrators, permanency of bullying displays on the Internet, and minimal constraints on time and space in which bullying can occur.5,6 Although adult monitoring and supervision is a problem for both traditional and cyber forms of bullying, adult monitoring and supervision of the online activities of teens is thought to be especially poor.7 Taken together, these features have led some researchers to speculate that cyberbullying may be more pernicious than traditional forms of peer aggression, though preliminary findings addressing this claim have been mixed.8

One of the major challenges facing researchers is how to conceptualize and define cyberbullying.9 “Bullying” is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated.”10 The extent to which this definition can be applied to cyberbullying is unclear, particularly with respect to whether online behaviors can adequately be considered “aggressive” in the absence of important in-person socio-emotional cues (i.e., vocal tone, facial expressions). Additionally, there is recognition that assessing ‘repetition’ is challenging in that a single harmful act on the internet has the potential to be shared or viewed multiple times.8 Many researchers have responded to this lack of conceptual and definitional clarity by creating their own measures to assess cyberbullying—very few of which capture the components of traditional bullying (i.e., repetition, power imbalance, and whether the aggressive behavior was “unwanted”).11

Given the lack of consensus on the definition of cyberbullying, it may not be surprising that estimated prevalence rates of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization vary widely around the world. In a small sample of global studies, estimates of prevalence ranged from 1–30% for cyberbullying perpetration (CB) and from 3–72% for cyberbullying victimization (CV). 12–15 Multiple factors have been proposed to explain this broad range of estimates. First, the term “cyberbullying” is sometimes used as an all-encompassing term to describe behaviors that may be seen as distinct to some researchers, such as a single act of Internet aggression or repeated acts of electronic harassment.9,16 The use of varied instruments and samples may also contribute to variation in prevalence.11 Further, cross-cultural, age, and time of measurement differences may meaningfully influence prevalence rates.17,18 In addition, variability in rates of technology use may contribute to variance in prevalence.18,19 Previous work has suggested that increased Internet use is associated with increased risk for cyberbullying.13 Thus, rates of cyberbullying may be lower in countries where technology use is lower than that of adolescents in the United States.

Determining the prevalence of cyberbullying specific to middle and high school students in the United States may guide priorities for inclusion of cyberbullying prevention in U.S. policy and school curricula. However, given the variation of prevalence rates reported across countries and over time, and the lack of consensus on a cyberbullying definition, setting such priorities is difficult. Thus, the present review had dual purposes. Specifically, the aims of this systematic review were to 1) evaluate the methodological rigor of studies attempting to measure the prevalence of cyberbullying in U.S. adolescents of middle and high school age (ages 10–19) using a standardized appraisal checklist20,21 and 2) report the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration, victimization, and dual perpetration/victimization status as reported by the highest quality studies. Our goals in providing this information were to evaluate the current state of the science, and to understand future directions for improving research quality on this important and timely topic.

METHODS

Study design

Our goal was to conduct a systematic review of the peer reviewed literature addressing cyberbullying literature, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. Given the heterogeneity of cyberbullying measurement instruments used in the included studies, we did not feel that a meta-analysis to determine overall cyberbullying prevalence between studies was feasible.

Search Strategy

In consultation with a health sciences librarian, searches were performed on 4 major databases of medical and social science literature—PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, and Web of Science—from inception to June 2015. Given that no Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were found specific to the topic of interest, we identified keyword search terms starting with the term cyberbullying and expanded the search to keywords associated with the manuscripts found in the initial search. The final list of search terms included the following keywords or keyword combinations: cyberbullying, electronic harassment, Internet bullying, and online aggression. To identify additional manuscripts, we searched the bibliographies of included manuscripts.

Study Manuscript Selection

Given that traditional bullying tends to peak in prevalence in the middle and high school years,17 we included English-language manuscripts that reported the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and/or victimization among middle school and high school aged adolescents through surveys of participants aged 10–19. Other manuscript inclusion criteria were: 1) conducted solely in the United States, or 2) data could be separated such that prevalence in the U.S. could be determined. Given that special populations such as students with disabilities and LGBTQ students have been found to be at higher risk for bullying than the general population of students, we excluded manuscripts that focused solely on special populations.4 In order to focus this review on cyberbullying, we excluded related concerns such as electronic dating violence or unwanted electronic sexual solicitation. We included manuscripts that reported cyberbullying across all available technology platforms including social media, texting and chat rooms.

In review of our included manuscripts, we discovered that some studies measuring cyberbullying prevalence were reported in multiple manuscripts. In order to systematically determine which manuscripts referred to a single study, we examined overlap in 1) title of the survey described in the manuscript’s Methods section (if available); 2) manuscript authors; and 3) similarities in total number of participants and sample demographics. Manuscripts that referred to the same study are grouped by study in the Appendix.

Quality Review Tool

Currently, a specific tool for assessment of the quality of cyberbullying studies is lacking. However, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations were created “to improve the quality of reporting of observational studies.”20 Thus, we used the STROBE statement to develop a quality review tool (QRT) for manuscripts reporting cyberbullying prevalence (Table 1). This tool consists of 21 items assessing study design and data collection as well as assessing the measurement of cyberbullying involvement. Each item was scored on a scale of 0 to 2 (0 = no reporting, 1 = partial criteria were met, 2 = full criteria were met) for a total possible score of 42 points. High scores indicate clear reporting of rationale, methodology, and results, which is essential in order to allow readers to assess a study critically. A lower score indicates less clarity in reporting, which may impede interpretation and application of a given study.20 Scoring was based on reported information in the manuscript; corresponding authors were also contacted by email when full details of the measurement tool used were not included in the manuscript. Two investigators (E.S. and J.F.) independently scored each manuscript and met to resolve score discrepancies by consensus. Interrater agreement showed that >90% of QRT scores were identical between reviewers. If a score discrepancy was not resolved by consensus, a third investigator (M.M.) reviewed the manuscript in question to determine the QRT score in question by majority; this occurred in 0.3% of scores.

Table 1.

Summary of Quality Review Tool (QRT) Scores for 81 Manuscripts Reporting Cyberbullying Prevalencea

| QRT Item | Brief Definition | Points Awardeda | Frequency of Studies, n (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Methods | ||||

| Recruitment timeframe | ||||

| Excellent | Year and month/season of study reported | 2 | 47 (58) | 1, 3, 4, 12–14, 18, 23, 26, 29, 37–38, 44, 49–50, 52–57, 59–62, 66–68, 70–74, 76–80, 82–83, 85–86, 88, 91–93 |

| Adequate | Year or month/season of study reported | 1 | 19 (23) | 27, 35, 41–43, 45–48, 58, 64, 69, 75, 81, 84, 87, 89–90, 94 |

| Study setting | ||||

| Excellent | Describes setting of two or more: university, classroom vs. online, or specific course(s) | 2 | 69 (85) | 1, 3, 4, 14, 15, 18, 22, 25–27, 29–31, 33–38, 40–41, 43–47, 49–64, 66–73, 75–80, 82–94 |

| Adequate | Describes single school setting, home setting, or classroom vs. online setting | 1 | 10 (12) | 12, 13, 23, 32, 39, 42, 48, 65, 74, 91 |

| Cyberbullying assessment instrument | ||||

| Validated | Cites validation study or previously published assessment for instrument/reports reliability (i.e. Cronbach’s α) AND other validity testing | 2 | 5 (6) | 18, 22, 29, 59, 68 |

| Partial reporting | Reports reliability testing without other validity testing OR reports other validity testing without reliability testing | 1 | 31 (38) | 1, 3, 15, 23, 24, 26–28, 32–34, 36, 38, 39, 47–49, 51, 54, 56, 60, 62, 63, 69, 72, 73, 80, 81, 86, 87, 91 |

| Criteria for classifying cyberbullying | ||||

| Excellent | Score cutoffs clearly defined | 2 | 60 (74) | 1, 12, 15, 18, 22–31, 33, 34, 39–50, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59–64, 66, 68, 69, 71, 72, 74–83, 85, 86, 88, 90–92, 94 |

| Adequate | Some discussion of criteria | 1 | 6 (7) | 35, 37, 65, 67, 89, 93 |

| Assessment response scale | ||||

| Excellent | Type of scale defined including exact values (e.g. 6-point Likert scale, “never” to “always”) | 2 | 64 (79) | 1, 12, 14, 15, 18, 22–26, 28–36, 39–47, 49, 50, 52–57, 59–62, 64, 66, 68, 69, 71–79, 81–83, 85, 86, 88, 90–94 |

| Adequate | Scale type defined (e.g. Likert, binary) | 1 | 8 (10) | 3, 13, 27, 38, 48, 63, 65, 67 |

| Cyberbullying variables (i.e. bully, victim, bully/victim) | Variables clearly defined | 2 | 78 (96) | 1, 3, 4, 12, 14, 15, 18, 22–35, 37, 39–94 |

| Inclusion/Exclusion criteria | ||||

| Excellent | Criteria defined with rationale | 2 | 30 (37) | 14, 18, 33–35, 39, 41–44, 49, 50, 52–58, 71, 72, 76–79, 85, 87, 92–94 |

| Adequate | Criteria defined without rationale | 1 | 3 (4) | 3, 60, 70 |

| Recruitment process | Reports process of recruiting participants | 2 | 45 (56) | 1, 4, 13, 15, 18, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29–37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 48–51, 59–62, 64, 69–71, 74, 76–80, 85, 86, 88, 91, 94 |

| Response rate | ||||

| Excellent | Response rate ≥ 80% | 2 | 13 (16) | 4, 12, 23, 28, 32, 38, 45, 47, 51, 53, 89, 90, 92 |

| Reported but low | Response rate <80% | 1 | 39 (48) | 14, 18, 26, 27, 30, 35–37, 39, 40, 42–44, 50, 52, 54–57, 59–61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73–77, 79, 85–87, 93, 94 |

| Sampling strategy | ||||

| Representative | Includes an established representative sampling method with citation or conducted by established survey firm | 2 | 30 (37) | 14, 18, 44–47, 50, 52–58, 71, 72, 74, 75, 78, 80–85, 87, 89, 90, 92, 93 |

| Somewhat representative | Strategy approximates an established representative method | 1 | 4 (5) | 30, 31, 76, 77 |

| Sample size | Rational for sample size reported | 2 | 29 (36) | 4, 14, 18, 26, 39, 44–49, 52, 53, 55, 62, 71–73, 75, 82, 84–90, 92, 93 |

| Statistical methods | Methods described including specific tests | 2 | 80 (99) | 1, 3, 4, 12–15, 18, 22–37, 39–94 |

| Results | ||||

| Participants | ||||

| Excellent reporting | Reported all eligibility numbers | 2 | 13 (16) | 39, 41–44, 52, 53, 71, 76, 77, 85, 92, 93 |

| Adequate reporting | Eligibility numbers partially reported | 1 | 7 (9) | 14, 18, 32, 36, 49, 50, 78 |

| Age | ||||

| Excellent | Mean age and range reported | 2 | 48 (59) | 1, 3, 12–15, 22, 24, 25, 29, 31–34, 39–43, 45–47, 50, 52–58, 62, 64, 68, 69, 73, 74, 76, 77, 79, 80, 83, 86–91, 94 |

| Adequate | Mean age or range reported | 1 | 19 (23) | 17, 26, 28, 36, 44, 51, 59, 63, 66, 71, 72, 75, 78, 81, 82, 84, 85, 92, 93 |

| Gender | Reports information about participants’ gender | 2 | 77 (95) | 1, 3, 4, 12–15, 18, 22–39, 41–74, 76–83, 85–93 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Excellent | Participants ethnicity fully reported | 2 | 56 (69) | 3, 4, 12, 13, 15, 18, 22, 24, 27, 29, 30, 32–47, 49, 54–57, 59, 61–68, 72–79, 83, 85, 87–91 |

| Adequate | Partial reporting (i.e. white/nonwhite only) | 1 | 15 (19) | 14, 26, 50–53, 58, 60, 69, 70, 81, 82, 86, 92, 94 |

| Missing data | ||||

| Excellent reporting | Explanation of characteristics of missing data/analysis of differences between participants with missing data and nonmissing data OR explanation of strategy used to account for missing data. | 2 | 16 (20) | 32, 41, 47, 52, 53, 55, 57, 62, 64, 72, 73, 86, 87, 92–94 |

| Partial reporting | Number of participants with missing data reported | 1 | 21 (26) | 1, 13, 15, 26, 31, 33, 39, 40, 43, 45, 46, 51, 56, 60, 68, 70, 71, 75, 89–91 |

| Number of participants meeting CB criteria | Number of participants meeting CB criteria reported | 2 | 78(96) | 1, 3, 4, 13–15, 18, 22–59, 60–64, 66–85, 87–94 |

| Average CB score overall and by item | ||||

| Excellent | Reported all overall and item scores with confidence intervals/SD | 2 | 11 (14) | 15, 32, 43, 53, 55, 57, 58, 61, 64, 83, 85 |

| Adequate | Scores partially reported | 1 | 35 (43) | 1, 3, 12, 13, 22, 23, 25, 28, 29, 33, 34, 36, 38, 40–42, 45, 46, 56, 59, 60, 62, 63, 65–68, 73, 75, 79, 81, 82, 84, 86, 91 |

| CB-specific items | ||||

| CB defined | ||||

| Excellent | CB defined with supporting background or citations | 2 | 52 (64) | 1, 3, 12, 15, 22, 24–27, 29, 32–36, 38–43, 46–50, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 61–63, 66–68, 71, 73–75, 79–83, 86–91 |

| Adequate | CB defined without citations | 1 | 10 (12) | 13, 18, 23, 30, 31, 45, 54, 60, 72, 85 |

| Availability of CB measurement instrument | Full instrument in manuscript, reference for obtaining instrument in paper, or authors made available by email | 2 | 63 (78) | 1, 3, 4, 12, 14, 15, 18, 22–29, 31, 33, 34, 37–42, 45–47, 49, 50, 52–57, 59–62, 64, 66–69, 71, 73–75, 77–83, 85, 86, 89–94 |

2 points = full reporting, 1 point = partial reporting. Studies with absent reporting (0 points) not included in Table.

Prevalence of Cyberbullying

In order to report the prevalence of cyberbullying as described in each manuscript, we utilized one of two methods: 1) direct extraction of prevalence rate reported within the manuscript; or 2) calculation of prevalence in manuscripts if both total number of subjects and number of subjects reporting cyberbullying behavior were reported. Several manuscripts reported frequencies of reported behaviors (i.e., responses on a Likert-type scale) but did not report specific criteria as to which frequencies were considered cyberbullying or not. These manuscripts were included in the QRT assessment and are described in supplemental content (see Appendix), but were excluded from the compilation of prevalence data represented in the Results

In instances in which multiple manuscripts used data from the same study, the prevalence reported in the manuscript with the highest QRT score was used and the other manuscripts were excluded from the compilation of prevalence data represented in the Results. Since this was the first application of the QRT to cyberbullying studies, standard QRT score cutoffs to delineate the “best” studies were unavailable. To approximate measure of quality relative to other studies within the review, studies were divided equally into three groups by QRT score to represent high, middle, and low quality studies.

RESULTS

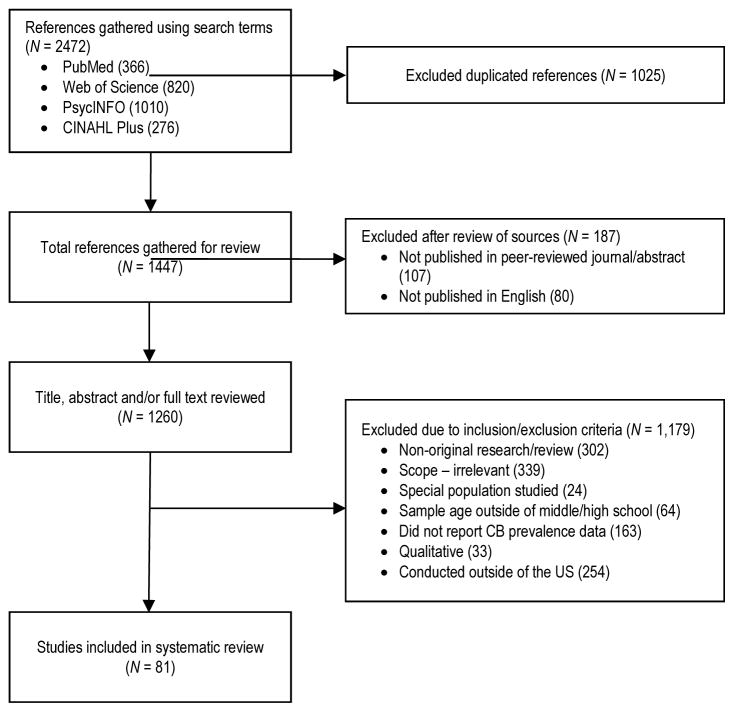

Our initial search yielded 1,447 nonduplicate manuscripts, of which 1,260 were included in the initial review of English-language peer-reviewed publications (Figure 1). Further exclusion was made of 302 non-original research manuscripts, 339 manuscripts that did not assess cyberbullying, 24 manuscripts that assessed only a special population, 64 manuscripts of participants outside of middle and high school ages, 33 qualitative manuscripts, 254 manuscripts of cyberbullying studies conducted outside of the United States, and 163 manuscripts that discussed cyberbullying but did not report prevalence, resulting in a final analysis of 81 manuscripts reporting on 58 unique studies spanning from the years 2003 to present (see Appendix). The Appendix presents key aspects of each reviewed manuscript.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Systematic Review Process Investigating Cyberbullying Prevalence.

CB indicates cyberbullying.

Quality

Using the QRT, quality assessment of the 81 included manuscripts ranged from total scores of 12 to 37 points out of a total possible 42 points, with an average score of 26.7 points (SD=4.6). Table 1 summarizes the results of the quality assessment, listing the manuscripts that scored either partial (1 point) or full (2 points) credit under each criterion. The most frequent categories in which manuscripts received no credit (0 points) included: use of a piloted or validated assessment for cyberbullying, reporting of eligible and ineligible subjects, and reporting of missing data. Manuscripts scored most highly in reporting of gender, description of analytic technique, and use of clearly defined variables.

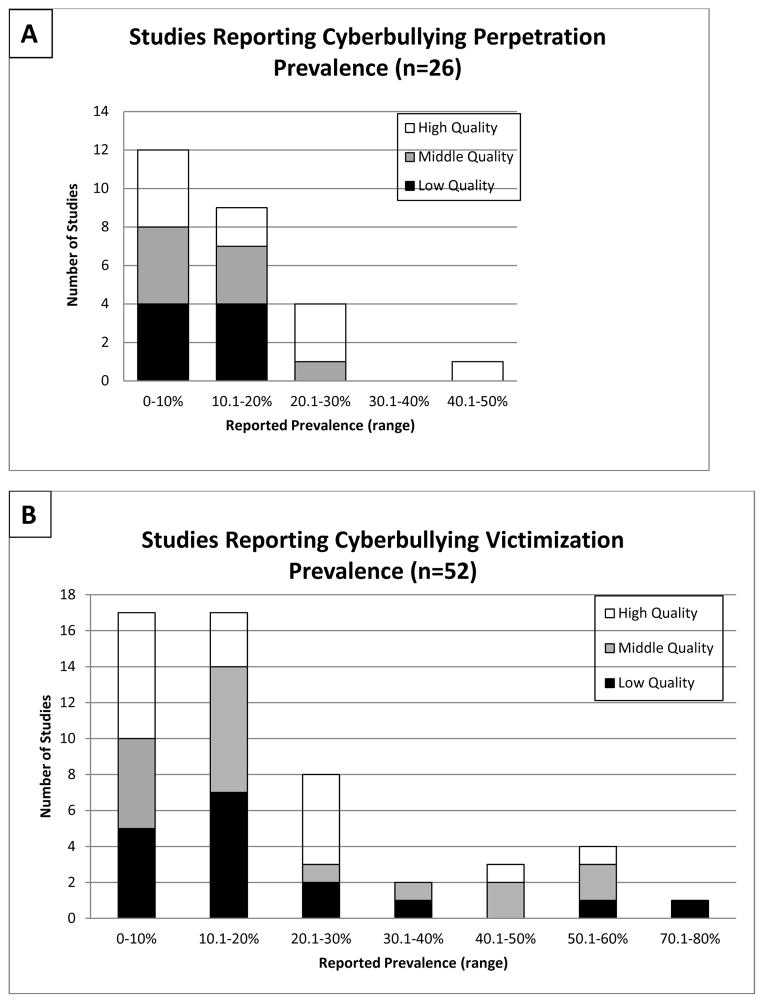

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Perpetration 1,3,12,14,18,22–57

Thirty-two unique studies (reported in a total of 41 articles) reported prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration (three reported perpetration only and 29 reported separate rates of perpetration and victimization) ranging between 1% and 41% (Figure 2). The time period over which reported cyberbullying perpetration occurred was inconsistent across studies; examples of time frames measured included “the last 30 days,”27,29 “the past couple of months,”30,45 and “the last year.”43,57 A range of terms were used when referring to the outcome of interest, including but not limited to “cyberbullying,”29,37 “cyber aggression,”27 “Internet harassment,”48,55 “online aggressive behavior,”14 and “electronic bullying.”30,32 Assessment instruments contained between 1 and 11 items on cyberbullying perpetration.

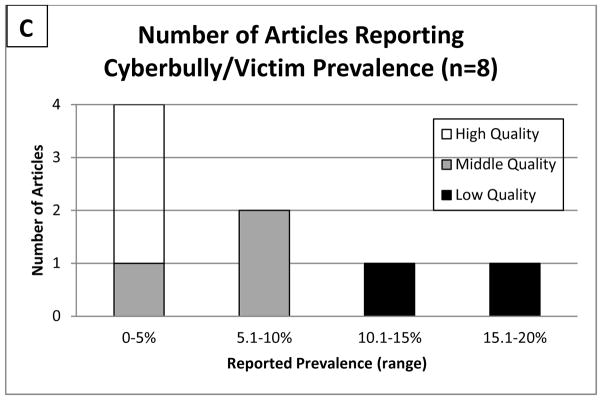

Figure 2. Prevalence of Cyberbullying Reported by Reviewed Studies*.

A, Perpetration (cyberbully) prevalence. B, Victimization (cybervictim) prevalence. C, Cyberbully/victim prevalence. High, middle, and low quality determined by top, middle, and low 1/3rd of quality review tool (QRT) scores within each manuscript category. *For duplicate manuscripts reporting data from the same study, data from the highest quality manuscript is represented in Figure.

Among high quality studies, the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration over various time periods was reported as follows: in the last 30 days, 4.9% and 21.8%;29,33 in the last couple of months, 4.3% and 8.9%;39,47 this school year (unspecified number of months), 9.4% and 12%;42,49 and in the last year, 15%, 25.4%, 29%, and 41%.18,43,53

Prevalence of Cyberbullying Victimization 1,3,4,12,13,15,18,23–26,28,30–33,35–46,48,50–54,56–94

Fifty-five unique studies (reported in a total of 73 articles) reported prevalence of cyberbullying victimization (26 reported victimization only and 29 reported separate rates of perpetration and victimization) ranging between 3% and 72% (Figure 2). The time period over which reported cyberbullying victimization occurred was again inconsistent across studies: examples of time frames measured included “the last 30 days,”33,70 “this school year,”23,42 “the last year,”67,85 and “ever.”73,80 A range of terms were used when referring to the outcome of interest, including but not limited to “cybervictimization,”35,46 “online harassment,”18,78 “electronic aggression,”70 “electronic victimization,”32,40 and “Internet harassment.”85,93 Assessment instruments contained between 1 and 14 items on cyberbullying victimization.

Among high quality studies, the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization over various time periods was reported as follows: in the last 30 days, 5.9%, 9%, and 29.4%;33,59,62 in the last couple of months, 7.1% and 9.8%;39,45 in the last three months, 24.5%;26 this school year (unspecified number of months), 13% and 24%;42,86 in the last year, 4.3%, 7%, 9%, 11%, 17%, 25.5%, and 40.6%;18,43,53,71,79,85 the past two years, 56%;72 and “ever,” 23%.73

Prevalence of Dual Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization 1,23,24,28,30,35,39,41,46,52

Although a total of 29 unique studies examined both cyberbullying perpetration and victimization separately, only 10 reported the prevalence of participants specifically in the dual bully/victim context (i.e. were both perpetrators and victims), with prevalence ranging between 2.3% and 16.7% (Figure 2). The three high-quality studies reported prevalence in the last couple of months of 2.3%39 and in the last year, 3% and 4.5%.41,52

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest a robust interest in the research community in studying cyberbullying prevalence among middle and high school aged adolescents, with 81 manuscripts (58 studies) reporting prevalence among United States adolescents in the last 12 years. We applied a quality review to manuscripts and found that manuscripts most often scored poorly using a validated measurement tool. Among these studies, we found varied prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization as well as variable terms used as outcomes including “cyberbullying,” “online harassment,” and “electronic bullying,” among others.

The quality of studies in this review was variable, but the quality ratings were often low. The majority of studies scored poorly on use of validated measures of cyberbullying, thus, the internal validity of these studies’ findings is called into question. Furthermore, many studies scored poorly based on failing to report missing data and missing descriptions of eligible and ineligible participants, which represents a threat to external validity. These quality concerns lead us to conclude that these reports of prevalence are difficult to generalize and often challenging to interpret.

The studies included in this review reported prevalence rates of cyberbullying perpetration from 1% to 41%, cyberbullying victimization prevalence rates from 3% to 72%, and cyberbully/victim rates from 2.3% to 16.7%. Even among high quality studies, the reported prevalence over equivalent time periods was variable. Previous literature has found higher prevalence of traditional bullying victimization compared to perpetration.95 However, we were unable to estimate overall prevalence for either perpetration or victimization due to the variability in measurement methods.

Variability across the reported prevalence of both perpetration and victimization was large; this wide range is likely related to several issues. First, the inconsistency in defining cyberbullying as applied to study populations very likely contributed to variability across measured outcomes between studies. For example, one survey queried respondents about others “repeatedly [trying] to hurt you or make you feel bad by e-mailing/e-messaging you or posting a blog about you on the Internet (MySpace)” and found prevalence of cybervictimization to be 9%,59 while another asked about “the use of the Internet, cell phones and other technologies to bully, harass, threaten or embarrass someone” and found cybervictimization prevalence to be 31%.38 Second, not all studies queried participants about the occurrence of cyberbullying over the same time period. Third, there were inconsistencies in the response options and analysis of responses across studies. Some studies had binary responses to questions while others had Likert scales; those with Likert scales often had non-validated varying scale cutoffs for determining whether a participant had experienced cyberbullying or not. Another systematic review has explored variability in cyberbullying measurement tools and called for further investigation of validity and reliability of existing tools.11 Whereas studies that assess traditional bullying have the benefit of using a consensus-based definition to measure the phenomenon of interest, variability in cyberbullying measurement tools is likely related to the lack of consensus on a definition of cyberbullying itself.

Strengths of this review are the inclusion of studies that examined cyberbullying prevalence both in isolation and in the context of traditional bullying, as well as inclusion of studies of cyberbullying across all available technological platforms. A recent meta-analysis compared prevalence of cyber and traditional bullying focused specifically on studies that assessed both types of bullying.95 This previous study concluded that the mean prevalence of cyberbullying was less than that of traditional bullying. However, in this review we included a full range of studies that assess prevalence of cyberbullying across all available platforms and found that, similar to traditional forms of bullying, the prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization still likely represents a significant burden to adolescents in the United States.

This systematic review has several limitations. First, several commonly cited studies of cyberbullying prevalence were excluded due to our strict inclusion criterion requiring that a study report prevalence in the United States; these studies were conducted in an online environment so had respondents from multiple countries and it was impossible to separate the United States participants from others. Similarly, studies that included participants under the age of 10 and had no separation of age groups were excluded. We also excluded studies sampling or oversampling special populations such as students with disabilities or LGBTQ youth, groups that may have unique experiences with cyberbullying. It is important that future research continue to examine cyberbullying in populations that may be at special risk; however, in order to determine broad policy and prevention priorities, we felt that our criteria should be strict to have consistency and applicability to our population of interest. Accordingly, our results are not intended to be generalizable outside of the general US middle and high school student populations. Furthermore, we did not search the grey literature (i.e. dissertations, government reports), and our results may be impacted by publication bias; however, our intent was to focus on the current state of quality in the peer-reviewed published literature.

Despite these limitations, this review emphasizes the importance of consistent, rigorous measurement of cyberbullying. Without a consensus on definition to guide measurement, studies of prevalence are likely to continue to show variability. Studies of traditional bullying have benefited from a consensus on definition. For example, the Olweus Bullying Scale is widely used for measurement of traditional bullying, and the CDC has recently released a standard definition of bullying,10 illustrating that standardization and consensus across the varied disciplines involved in studying bullying is a challenging but possible task.11 Unfortunately, this definition cannot easily be applied to cyberbullying given the unique affordances of the online medium, such as greater anonymity and the potential for an act of aggression to spread widely and rapidly in the public arena. Further, in order to meet the criteria of traditional bullying, aggressive acts must be repeated over time; this criteria may not be critical within an online context, as a single act of online aggression may be sufficiently severe as to qualify as cyberbullying. Further, repetition may have unique meaning within an online context. There is virtually no limit to the number of times a single aggressive act can be viewed or re-experienced by an individual, his or her peer group, and—in some instances—the world. Following the standardization of terminology and definition for cyberbullying, a standard instrument for measurement must also be developed, validated, and applied to populations. The ideal instrument should incorporate existing instrument properties and language that is developmentally appropriate as well as sensitive to the constant evolving nature of digital media. Consistent use of the instrument across grade levels and geographical regions will then be important to measure demographic trends and to elicit a more accurate picture of the prevalence of this phenomenon.

In addition, in order to draw firm conclusions about the prevalence of cyberbullying, it is incumbent upon researchers to improve the quality of our studies and our reporting of results. The ideal prevalence study will offer a clear and explicit definition of cyberbullying and will choose a psychometrically sound assessment instrument that reflects that definition. Multi-item measures wherein the researcher identifies specific behaviors that constitute cyber-aggression, with follow-up questions to determine repetition, power differentials, and the degree to which the aggressive act(s) was (were) ‘unwanted’, may offer the most flexibility and have the potential to minimize respondent perceptual bias.96 Consistent and widespread use of an accepted measure will allow for researchers to compare prevalence rates across time, settings, and samples and will allow for true meta-analytic techniques. Notably, all of the studies included in the present review have relied exclusively on retrospective self-report of cyberbullying, the validity of which may be threatened by inaccurate or biased recall. Researchers assessing prevalence may wish to consider concurrent or prospective designs to more accurately capture cyberbullying prevalence. Use of probability sampling is also recommended in the ideal study, as convenience samples may produce biased prevalence estimates and do not permit generalization of findings. If utilizing a probability sampling design, accurate reporting of response rates is essential for evaluating the results. Finally, as is the case for all observational studies, researchers should take care to report how missing data were handled, whether there were inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study, how inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied, and when the data were collected. This latter point is particularly critical for the study of cyberbullying prevalence, which may be influenced by increased awareness and increased exposure and access to technology over time.18

Our study has important implications. The news media is rife with stories of cyberbullying, and extreme cases linked to suicides by the victim have been reported. While these cases have received much attention, the range of cyberbullying prevalence found in this review suggests that cyberbullying may be a common occurrence among today’s youth and could lead to other negative consequences outside of the most severe cases. Educators, providers and researchers can play a role in prevention and intervention regarding cyberbullying. However, this systematic review suggests that the current state of the science is that studies assessing prevalence of cyberbullying use a variety of terms and tools, which may contribute to confusion rather than clarity regarding this growing concern. Understanding the impact of cyberbullying on victims and perpetrators, and associations with later health effects are important next steps for this field. These tasks cannot be accomplished without a sound definition and understanding of cyberbullying as an entity. Thus, this review provides a call to action for the development of evidence-based tools. Examination of the high quality studies included in this review may provide a starting point for guiding future work.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

Using an evidence-based quality tool, this review provides a detailed critical assessment of studies of cyberbullying prevalence in U.S. adolescents as well as a call for cyberbullying-related policy to incorporate quality evidence based on standardized definitions and measurement instruments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant NRSA-2T32/MH020021-16 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: Unützer). The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

List of Abbreviations

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- CB

cyberbullying

- QRT

Quality review tool

Appendix. Characteristics of Included Articles Reporting Cyberbullying (CB) Prevalence

Note: Articles are grouped by study data set used, when known

Individual studies reporting prevalence data

Allen, 20121

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying; cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 24 |

| Sample | 820 high school students from an affluent suburb in northeastern United States assessed from Feb–Jun 2009 |

| Demographics | 14–19 years of age (M = 16.0, SD = 1.23); 51.4% female, 88.9% Caucasian, 3.1% African American, 1.3% Hispanic, 6.6% Asian |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 2-items; reporting time frame not specified. |

| CB criteria | “behavior occurs 2–3 times per month or more” |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 1.0% |

| Victim: 3.2% |

Ang et al., 20142

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 27 |

| Sample | 425 middle school students from five middle schools in Kentucky; assessment time period “toward the end of the school term” |

| Demographics | 11–16 years of age (M = 13.0, SD = .98); 59.5% female; 90.6% Caucasian, 2.4% African American, 1.6% Hispanic, 1.2% American Indian, 2.3% Other, 1.9% Missing |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey previously piloted and validated; 9-items (Cronbach’s α= .91); reporting time frame “during the school term”. |

| CB criteria | No criteria for point estimate of CB prevalence. ‘Infrequent bullies’ = engaging in cyberbullying a couple to a few times in the school term; “Frequent bullies” = weekly or more cyberbullying |

| CB Prevalence | Bully |

| Frequent: 1.1% | |

| Infrequent: 16.8% |

Note: Study conducted in US and Singapore; only data for US participants is reported.

Barboza, 20153

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 22 |

| Sample | 5,589 adolescents in a nationally representative sample assessed at one of two waves in 2011 |

| Demographics | 12–18 years of age (M = 14.77, SD = 1.99); 49% female; 80% white, 20% non-white |

| Assessment Tool | National Crime Victimization Survey: School Crime Supplement; 4 items; reporting time frame “during this school year” |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response to any cyberbullying item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 14.7% |

Bauman, 20104

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 24 |

| Sample | 221 students in grades 5–8 from a rural school in southwestern United States assessed in October, year unspecified |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 54% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 9-items to assess cyberbullying (α = .89), 12 to assess cybervictimization (α = .85); reporting time frame “current school year” ~2 months. |

| CB criteria | Z score of ≥ +1.0 on either measure |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 3% |

| Victim: 4% | |

| Bully/Victim: 5% |

Note: Prevalence values are those reported in main text of article; however, the abstract reports bully prevalence of 1.5%, victim prevalence of 3%, and bully/victim prevalence of 8.6%.

Bossler et al., 20125

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Online harassment |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 26 |

| Sample | 434 middle and high school students from Kentucky assessed in the spring of 2008 |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 51.2% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey; 1 item to assess ‘harassment’ perpetration, 4 to assess victimization; victimization items previously piloted, though validation data not reported; reporting time frame within the past year. |

| CB criteria | Any victimization in the last 12 months |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 35.3% |

Burton et al., 20136

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying, cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 21 |

| Sample | 851 school-age students; sampling frame and assessment time period not specified |

| Demographics | 10–16 years of age (M = 12.93, SD = .92); 58.9% female; 91% Caucasian |

| Assessment Tool | Modified version (not previously piloted or validated) of the Traditional Bullying and Victimization Scale; 9-items to assess perpetration (Cronbach’s α = .894), 9-items to assess victimization (Cronbach’s α = .903) within the past year. |

| CB criteria | At or above 75th percentile for bullying and/or victimization measures |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 8.8% |

| Victim: 4.9% | |

| Bully/Victim: 16.7% |

Byrne et al., 20147

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 23 |

| Sample | National sample of 454 adolescents; assessment time period not specified |

| Demographics | 10–16 years of age (M = 12.93, SD = 1.99); 51% female; race/ethnicity not specified |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 1 item to assess perpetration, 2 items to assess victimization; reporting time frame not specified. |

| CB criteria | Dichotomized to any response greater than 1 (never) |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 29.74% |

| Victim: 16.3% |

Connell et al., 20148

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 29 |

| Sample | 3,867 students grade 5–8 in 14 middle schools in northeastern US state |

| Demographics | Average age 12.4; 54% female; 62.4% White |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 3 items assessing perpetration (Cronbach’s α = .728), 3 items to assess victimization (Cronbach’s α = .702) since the beginning of the school year (~3 months) |

| CB criteria | Having engaged in the behavior or experienced victimization |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: Females 16.0%, Males 10.5% |

| Victim: Female 30.1%, Males 17.9% |

Elgar et al., 20149

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying Victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 28 |

| Sample | 18,834 students (ages 12–18) from 49 schools in the Midwestern United States assessed during 2012 |

| Demographics | 12–18 years (M = 15.0, SD = 1.7); 50.7% female; 70.6% White, 7.6% Black, 6.6% Hispanic, 7.0% Mixed, 8.8% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author-designed survey not previously piloted or validated; one-item to assess victimization; response options: never, rarely, sometimes, or often; reporting time frame past 12 months |

| CB criteria | “at least once during the previous 12 months” |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 18.6% |

Gable et al., 201110

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 21 |

| Sample | 1,366 students in grades 7 and 8 from three middle schools (one urban, one suburban, and one rural) in United States; assessment time period not specified |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 48.8% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Author derived survey not previously piloted or validated; 3-items to assess victimization, 7 to assess bullying; reporting time frame not specified |

| CB criteria | Not reported; latent class analysis used to categorize sample into one of four groups (bully, victim, bully/victim, neither bullies nor victims). |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 6% |

| Victim: 5% | |

| Bully/Victim: 15% |

Gan et al., 201311

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 12 |

| Sample | 1,087 students in grades 9–12 from Chapel Hill, North Carolina; assessment time period not specified |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 51% female; 51% Caucasian, 13% African American, 6% Hispanic, 19% Asian, 11% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author-designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 2-items to assess cybervictimization; reporting time frame not specified; |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response to any item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 18% |

Gibson-Young et al., 201412

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying; Electronic Bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 25 |

| Sample | 6,212 students in grades 9–12 from 78 public high schools in Florida assessed in the spring of 2011 |

| Demographics | Mean age 16 years; 49% female; 46% Caucasian; 22.7% Black, 26.2% Hispanic, 1.9% Asian |

| Assessment Tool | 2011 Florida YRBS; one question to assess cybervictimization during the past 12 months, response options yes/no. |

| CB criteria | Yes response to cybervictimization item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 12.4% |

Goebert et al., 201113

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 22 |

| Sample | 677 students in grades 9–12 from Hawaii assessed in the spring of 2007 |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 60.2% female; 5.5% Caucasian, 59.5% Filipino, 29% Native Hawaiian, 6% Samoan |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 5-items to assess cybervictimization within the past year. |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response to any item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 56.1% |

Hase et al., 201514

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 28 |

| Sample | 1225 students from five middle and high schools in Southern Oregon were assessed in the fall of 2012. |

| Demographics | Mean age = 14.15, SD = 1.94; 47.88% female; 69.8% Caucasian; 13.31% Latino, 4.24% Asian or Asian American, 3.35% African American, 7.35% bi- or multiracial |

| Assessment Tool | Cyberbullying Questionnaire (Ang & Goh, 2010); 9 items to assess victimization. Response options: not in the past month, once in the past month, 2 or 3 times in the past month, about once a week, or several times a week. (Cronbach’s α = .90). Reporting timeframe past month |

| CB criteria | “experiencing one or more forms of cyberbullying two or three times or more in the past month” |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 16.32% |

Hinduja & Patchin, 201315

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying offending |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 31 |

| Sample | 4,441 students from 33 middle and high schools assessed in spring of 2010. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 49.10% female; 37.3% Caucasian, 23.9% African American, 24.5% Hispanic, 4.4% Asian, .9% Native American, 2.5% Multiracial, 5.8% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey previously piloted; 9 items to assess perpetration within the previous 30 days (Cronbach’s α = .965). |

| CB criteria | Answered “a few times” “many times” or “every day” to any item |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 4.9% |

Holt et al., 201416

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 24 |

| Sample | 1,972 students from 14 middle and high schools in North Carolina assessed 6 weeks into the school year |

| Demographics | Age range 11–18 (M = 13.89, SD = 1.92); 52% female; 73% white, 27% other. |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated, 2-items to assess harassing emails and texts from students in school “since school began.” Response options: 0 times, 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–9 times, and 10 or more times. (Cronbach’s α = .767). |

| CB criteria | Binary composite score created; any victimization in past 6 weeks |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 12% |

Johnson et al., 201117

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Electronic Aggression |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 18 |

| Sample | 832 students in grades 9–12 from 22 public high schools in Boston assessed from January to April in 2008. |

| Demographics | Age not reported, 100% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Shortened and adapted items (not previously piloted or validated) from an existing survey on ‘nonphysical bullying’; 1 item to assess victimization within the previous 30 days |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response to item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 8.4% |

Juvonen & Gross, 200818

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 20 |

| Sample | 1,454 adolescent users of www.bolt.com representing all 50 states were assessed from August through October 2005 |

| Demographics | 12–17 years of age (M=15.5, SD=1.47); 75% female; 66% Caucasian, 12% African American, 9% Hispanic, 5% Asian/Pacific Islander |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 5 items to assess cybervictimization within the past year. |

| CB criteria | Not reported |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 72% |

Kessel Schneider et al., 201219

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 22 |

| Sample | 20,406 students in grades 9–12 from 22 high schools in the Boston metro area assessed in fall of 2008. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 50.40% female; 75.2% Caucasian, 2.8% African American, 5.8% Hispanic, 3.9% Asian, 12.3% Mixed/other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 1 item to assess cybervictimization within the past year. |

| CB criteria | Not reported |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 15.8% |

Khurana et al., 201520

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Online harassment |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 32 |

| Sample | 629 adolescent children of a nationally representative sample of parents assessed in March 2012 |

| Demographics | 12–17 years old, 49% female, race/ethnicity not specified |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated, 2 items assessing unwanted posts and upsetting emails or instant messages in the past 12 months; response options: yes, no, don’t know, and don’t want to answer. |

| CB criteria | ‘Yes’ response to either item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 25.5% |

Kowalski & Limber, 200721

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Electronic bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 22 |

| Sample | 3,767 students in grades 6–8 from 6 elementary and middle schools in the southeastern and northwestern United States; assessment time period not specified. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 50.84% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 23-items to assess ‘experiences with electronic bullying’; reporting time frame “past couple of months” |

| CB criteria | “once or twice” or more often |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 4% |

| Victim: 11% | |

| Bully/Victim: 7% |

Kowalski et al., 201222

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 24 |

| Sample | 4,531 students in grades 6–12 from 8 schools in different regions throughout the United States; assessment time period not specified. |

| Demographics | 11–19 years of age (M=15.2, SD=1.8); 50.17% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 1 item to assess perpetration, 1 item to assess victimization within the “past couple of months” |

| CB criteria | At least once in the previous two months |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 10.9% |

| Victim:17.3% |

Kowalski & Limber, 201323

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 27 |

| Sample | 931 students in grades 6–12 from 2 schools in Pennsylvania assessed in fall of 2007. |

| Demographics | 11–19 years of age (M=15.16, SD=1.76); 47.16% female; race/ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey previously piloted (no validation data reported); 1 item to assess perpetration, 1 to assess victimization “within the past couple months.” |

| CB criteria | No criteria defined for point estimate of CB prevalence. Provides rates for participants who endorsed “at least once” and “two or three times a month or more” |

| CB Prevalence | Bully |

| At least once: 6.1% | |

| 2–3+x/month: 2.5% | |

| Victim | |

| At least once: 9.9% | |

| 2–3+ x/month: 4.0% | |

| Bully/Victim | |

| At least once: 5.3% | |

| 2–3+x/month: 1.9% |

Litwiller & Brausch, 201324

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyber bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 29 |

| Sample | 4,693 students from 27 high schools in a rural area of a Midwestern state assessed in spring of 2008 |

| Demographics | 14–19 years of age (M=16.11, SD=1.20); 49% female; 89% Caucasian, 1.5% African American, 1.5% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 2% American Indian, 1% Native HI/Pac Island, 3.6% Multiracial |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 3 items to assess lifetime history of cybervictimization (Cronbach’s α = .71). |

| CB criteria | Not defined |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 23% |

Mesch, 200925

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 28 |

| Sample | National sample of 935 adolescents assessed October and November of 2006. |

| Demographics | 12–17 years of age (M=14.71, SD=1.68); 49% female; 88.7% Caucasian, 11.3% African American; Other race/ethnicities not reported. |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 5 items to assess cybervictimization, time frame not specified. |

| CB criteria | Yes response to any item |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 40% |

Messias et al., 201426

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying; electronic bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 27 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of high school students (CDC Youth Risk Behaviors Survey; N = 15,425) assessed in 2012 |

| Demographics | Students in grade 9–12; gender not specified; 1.89% American Indian/Alaska Native, 3.01% Asian, 17.94% Black or African American, 1% Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, 40.01% White, 14.44% Hispanic/Latino, 15.56% Multiple-Hispanic, 4.22% Multiple-Non-Hispanic |

| Assessment Tool | One item to assess electronic bullying in past 12 months, yes/no response option |

| CB criteria | Yes response |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 16.2% |

Mitchell et al., 201527

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Technology-involved peer harassment |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 30 |

| Sample | National sample of 791 youth (Technology Harassment Victimization Study) assessed between December 2013 and March 2014. |

| Demographics | Age 10–20 (M = 14.7, Linearized SE = .2); 51% female; 58.8% White non-Hispanic, 12.6% Black non-Hispanic, 8.1% other race non-Hispanic, and 20.6% Hispanic, any race. |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; assessed harassment incidents via internet and cell phone in the past year; response options yes/no |

| CB criteria | Reported at least one incident in the past year |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 17% |

Moore et al., 201228

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Electronic bullying; electronic victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 29 |

| Sample | 855 7th and 8th grade students from a school in the southeastern U.S. assessed in the Spring of 2009 |

| Demographics | Mean age= 13 years, SD = .76; 52.16% female; 59% Caucasian, 28% African American, 2.6% Hispanic, 3% Asian/Pacific Islander |

| Assessment Tool | Modified version of the “Electronic Bullying Questionnaire,” piloting and validation data not reported; 4 items to assess victimization and 4 items to assess bullying within “the past couple months” |

| CB criteria | Not clearly defined by authors but appears to be any endorsement of any of the 4 bullying or victimization behaviors; “chronic bullying/victimization” group defined as those who endorsed bullying or victimization ‘several times a week.’ |

| CB Prevalence | Bullying |

| Any: 14% | |

| Chronic: 1.4% | |

| Victim | |

| Any: 20% | |

| Chronic: 3% |

Peleg-Oren et al., 201229

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying, cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 23 |

| Sample | 44,532 middle school students from Florida public schools assessed in 2008. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 48.7% female; 42% Caucasian, 19% African American, 24% Hispanic, 14.9% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 1 item to assess perpetration, 1 to assess victimization in the previous 30 days |

| CB criteria | Any involvement as a victim and/or perpetrator in the last 30 days |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 5.2% |

| Victim: 3.5% | |

| Bully/Victim: 2.9% |

Note: Prevalence is reported as weighted percentages.

Pelfrey and Weber, 201330

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying victimization; cyberbullying perpetration |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 21 |

| Sample | 3,403 students from 23 middle and high schools in a large, urban school district in a Midwest city; time frame of assessment not specified. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; describe range as “12 or less to 18 or up”; 50.8% female; 10% Caucasian, 63.6% African American, 23.5% Hispanic, 4.2% American Indian, 7.7% Asian |

| Assessment Tool | Shortened version of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey; piloting and validation data not reported; Cronbach’s alpha for the shortened measure = .605; number of cyberbullying/victimization items not specified; time frame of measure not specified |

| CB criteria | Not defined |

| CB Prevalence | Bully |

| Few x/year = 9.1% | |

| Few x/month = 3.9% | |

| Few x/week = 3.5% | |

| Every day = 2.9% | |

| Victim | |

| Few x/year = 5.3% | |

| Few x/month = 2.5% | |

| Few x/week = 1.9% | |

| Every day = 1.4% |

Pergolizzi et al., 200931

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 21 |

| Sample | 587 7th and 8th grade students from 4 middle schools in Florida, California, and Maryland assessed in May and June of 2006. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 57.7% female; 25.1% Caucasian, 13% African American, 53.6% Hispanic, 3.2% Asian, 5.1% Other/Multiethnic |

| Assessment Tool | Previously piloted Child Abuse Prevention Services Middle School Bullying Survey; piloting and validation data not reported; 1 item to assess perpetration, 1 item to assess victimization |

| CB criteria | Victim: “has been the victim of a cyberbully at least a little of the time;” Bully: “yes” response |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 15.2% |

| Victim: 27.9% |

Pergolizzi et al., 201132

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cybervictim |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 19 |

| Sample | 346 7th and 8th grade students from middle schools in Florida and California assessed in April and June of 2008. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 50.6% female; 43% Caucasian, 24% African American, 13% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 2% Native American, 11% Multiethnic, 6% Missing |

| Assessment Tool | Previously piloted Child Abuse Prevention Services Middle School Bullying Survey, piloting and validation data not reported; 1 item to assess perpetration, 1 item to assess victimization |

| CB criteria | Victim: has been the ‘victim of a cyberbully at least a little of the time;’ Bully: yes response |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 17.6% |

| Victim: 31.1% |

Price et al., 201333

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyber bullying; cyber victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 32 |

| Sample | 211 6th and 7th grade students from a rural and ethnically diverse middle school in Hawaii; assessment time period not specified. |

| Demographics | 10 to 13 years of age (M = 11.26, SD = .7); 50% female; 4.3% Caucasian, 9.5% Japanese, 4.3% Filipino, 2.4% Marshallese,1.4% Native Hawaiian, 74.8% Multiethnic, 3.5% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey (Cyber Bully/Victim Questionnaire) not previously piloted or validated; 11 items to assess perpetration (Cronbach’s α = .96), 11 items to assess victimization (Cronbach’s α = .81) in the past couple months |

| CB criteria | Engaged in any of the listed activities 2 or 3 times a month or more |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 4.3% |

| Victim: 7.1% | |

| Bully/Victim: 2.3% |

Raskauskas & Stoltz, 200734

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Electronic bullying, electronic victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 25 |

| Sample | 84 school age students participating at 2 youth development events, one in an unidentified rural locale, the other in a suburb of a large, west coast city; assessment time period not specified. |

| Demographics | 13–18 years of age (M = 15.35, SD = 1.26); gender not reported; 89.3% Caucasian, 3.6% African American, 3.6% Hispanic, 2.4% Asian, 1.2% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey, piloting and validation data not reported; 2 to assess perpetration, 3 to assess victimization ‘within this school year.’ |

| CB criteria | Any “yes” response |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 21.4% |

| Victim: 48.8% |

Rice et al., 201535

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 28 |

| Sample | 1285 students from urban and suburban middle schools in Southern California assessed in 2012 |

| Demographics | Mean age = 12.29, SD = .86; 48.3% female; .41% American Indian or Alaska Native, 3.40% Asian, 18.31% Black or African American, 59.62% Hispanic or Latino, 1.82% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 15.18% White, 1.26% Mixed |

| Assessment Tool | 2 items, one to assess cyberbullying perpetration and one to assess cyberbullying victimization during the past 12 months; validation data not reported; response options: never, once or twice, a few times, many times, and every day. |

| CB criteria | Dichotomized responses for each question, but no discussion of score cutoffs |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 4.98% |

| Victim: 6.59% | |

| Bully/Victim: 4.27% |

Roberto et al., 201436

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 30 |

| Sample | 425 students from one middle school in a large Southwestern city, assessed in May (year not reported) |

| Demographics | 10–15 years of age (M = 12.58, SD = 1.02); 53% female; 58% Caucasian, 37% African American, 34% Asian, 39% Hispanic, 35% American Indian, 41% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey, not piloted or validated; 2 items to assess perpetration, and 2 items to assess victimization during current school year (~9 months) |

| CB criteria | Any “yes” response |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 12% |

| Victim: 24% |

Note: Total for race is more than 100% because participants were asked to check all that apply.

Sontag et al., 201137

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 31 |

| Sample | 300 6th–8th grade students from two middle schools in a small city in the southeastern United States assessed during the 2006–2007 school year. |

| Demographics | Mean Age = 12.9, SD = 1.0; 63.2% female; ~52% Caucasian, 27% African American, 11% Hispanic, 10% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Adolescent Peer Experiences (APEX); piloting and validation data not reported; 2 items to assess perpetration and 2 to assess victimization within the past year. |

| CB criteria | Victim: experiencing at least one of the two victimization items in the past year; Bully: engaging in cyber aggression at least once or twice in the past year |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 25.4% |

| Victim: 40.6% |

Steiner & Rasberry, 201538

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Electronic bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 15 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 13,583 high school students assessed in 2013 (2013 YRBS) |

| Demographics | Grades 9–12; gender not reported; ethnicity not reported |

| Assessment Tool | One question about electronic bullying in past 12 months; piloting and validation data not reported; response options not provided |

| CB criteria | Not reported |

| CB Prevalence | Victim:14.8% |

Stewart et al., 201439

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 28 |

| Sample | 736 middle and high school students from 6 public schools in Mississippi; assessment time period not specified |

| Demographics | 11–18 years of age (M = 14.52, SD = 1.86); 49.20% female; 89.7% Caucasian, 6.2% African American, 2.2% Multiracial, 1.93% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey (Cyberbullying Scale ; CBS) not previously piloted or validated; 14 items to assess victimization in the past couple months (α = .94). |

| CB criteria | Non-zero score on the CBS |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 58.7% |

Turner et al., 201340

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyber bullying victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 31 |

| Sample | 1,874 6th–12th grade students from 14 middle and high schools in central North Carolina assessed in October of 2008. |

| Demographics | 11–18 years of age (M = 13.77, SD = 1.92); 51% female; 70% Caucasian, 30% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey; 2 items to assess victimization (α = .767); reporting time frame “this school year” ~2 months |

| CB criteria | Any “yes” response |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: “approximately 13%” |

Turner et al., 201441

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Internet victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 27 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 3,164 school-aged youth assessed in 2011 (National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence II) |

| Demographics | Age 6–17* (M = 12.0, SD = 3.4), 48.2% female; 68.4% white non-Hispanic, 12.4% Black non-Hispanic, 5.7% other race non-Hispanic, 13.5% Hispanic any other race. |

| Assessment Tool | “Enhanced” version of the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (Finkelhor, Hamby, Ormrod, & Turner, 2005); 3-items to assess internet victimization perpetrated by a peer in the past year; response options not reported |

| CB criteria | Not reported |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 9.3% |

Note: Prevalence based on subsample of youth ages 10–17

Werner et al., 201042

| CB prevalence main study objective | No | |

| Term Used | Internet aggression, internet victimization | |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 20 | |

| Sample | Longitudinal sample of middle school students from a small, northwestern city assessed “in the middle of spring semester” (T1, n = 330) (T2, n = 150) | |

| Demographics | T1 | T2 |

| Age not reported; 57% female; race/ethnicity not reported | Age not reported; 51% female; race/ethnicity not reported | |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey not previously piloted or validated; 4 items to assess perpetration (Cronbach’s α = .70 at T1, .71 at T2), 4 items to assess victimization (Cronbach’s α = .85 at T1, .67 at T2) in the previous 30 days | |

| CB criteria | “any acts of internet aggression (as perpetrator or victim) in the previous month” | |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 18% | |

| Victim: 17% | ||

Note: Authors assessed bullying/victimization at both time points, but do not indicate which time point prevalence rates are from.

Wigderson & Lynch, 201343

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyber-victimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 28 |

| Sample | 388 students in grades 6–12 from one rural northeast school assessed in the fall of 2011 |

| Demographics | 11–18 years of age (M = 14.3, SD = 2.0); 48% female; 87.1% Caucasian, 2% African American, 2.1% Hispanic, 1.3% Asian, 1.8% Native American, 5.7% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey; 6 items to assess victimization in the past 9 months (α = .73) |

| CB criteria | “at least one experience” |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 54.4% |

Williams & Guerra, 200744

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Internet bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 30 |

| Sample | 1,519 5th, 8th, and 11th graders enrolled in 46 Colorado schools (61% rural, 39% urban) assessed during fall 2005 (demographic data) and spring 2006 (bullying data). |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 55% female; 62% Caucasian, 6.4% African American, 26.9% Hispanic, 3.5% Asian, 1.2% Native American |

| Assessment Tool | Author designed survey to assess bullying perpetration broadly (alpha coefficient = .73); 1 item to assess cyber bullying perpetration during ‘this school year.’ |

| CB criteria | “bullying behavior one or more times” |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 9.4% |

Yahner et al., 201545

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyber bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 18 |

| Sample | 5,647 youth from 10 middle and high schools in rural New York, urban Pennsylvania, and suburban New Jersey; assessment period not specified. |

| Demographics | Ages 14–17; 51% female; 75% White/Caucasian; other race/ethnicities not specified |

| Assessment Tool | 12-items adapted from Griezel (2007; unpublished master’s thesis) to assess cyber victimization (Cronbach’s α = .898) and perpetration (Cronbach’s α = .974) in the prior year. Response options not specified. |

| CB criteria | Not reported |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 8% |

| Victim: 17% |

Studies reported by multiple articles

Health Behavior in School Aged Children survey, 2005–06

Wang et al., 200946

| CB prevalence main study objective | Yes |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying, Cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 30 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 7,182 students in grades 6 through 10 assessed from 2005 to 2006. |

| Demographics | Mean age = 14.3, SD = 1.42; 52.2% female; 42.6% Caucasian, 18.2% African American, 26.4% Hispanic |

| Assessment Tool | Health Behavior in School Aged Children; piloting and validation data not reported; 2 items to assess perpetration, 2 items to assess victimization in the ‘past couple of months’ |

| CB criteria | Involvement at least once or twice a month in the past couple of months |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 8.3% |

| Victim: 9.8% |

Wang et al., 2010a47

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 30 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 7,475 students in grades 6 through 10 assessed from 2005 to 2006. |

| Demographics | Age not reported; 51.5% female; 42.2% Caucasian, 18.7% African American, 26.4% Hispanic |

| Assessment Tool | Health Behavior in School Aged Children; piloting and validation data not reported; 2 items to assess victimization in the ‘past couple of months’ |

| CB criteria | Any involvement |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 10.1% |

Wang et al., 2010b48

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 27 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 6,939 students in grades 6 through 10 assessed from 2005 to 2006. |

| Demographics | Mean age = 14.4, SD = 1.41); 51.2% female; 43.5% Caucasian, 18.2% African American, 25.5% Hispanic |

| Assessment Tool | Health Behavior in School Aged Children; piloting and validation data not reported; 2 items to assess victimization in the ‘past couple of months’ |

| CB criteria | “A dichotomous variable was created with two categories: noninvolved and involved” |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 9.9% |

Wang et al., 201149

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying, Cybervictimization |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 29 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 7,313 students in grades 6 through 10 enrolled in public, private, and Catholic schools assessed from 2005 to 2006. |

| Demographics | Mean age = 14.2, SD = 1.42; 52% female; 42.3% Caucasian, 18.5% African American, 26.4% Hispanic |

| Assessment Tool | Health Behavior in School Aged Children; piloting and validation data not reported; 2 items to assess perpetration, 2 items to assess victimization in the ‘past couple of months’ |

| CB criteria | No criteria defined for point estimate of CB prevalence. Frequent Involvement = ‘two or three times a month’; Occasional Involvement = ‘only once or twice’ |

| CB Prevalence | Bully |

| Never: 91.5% | |

| Occasional: 4.2% | |

| Frequent: 4.3% | |

| Victim | |

| Never: 90.0% | |

| Occasional: 5.6% | |

| Frequent: 4.3% | |

| Bully/Victim | |

| Never: 86.2% | |

| Occasional: 1.6% | |

| Frequent: 1.9% | |

| Mixed: 1.1% |

Wang et al., 201250

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyber bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 32 |

| Sample | Nationally representative sample of 7,508 students in grades 6 through 10 enrolled in public, private, and Catholic schools assessed from 2005 to 2006. |

| Demographics | Mean age = 14.2, SD = 1.4; 51.5% female; 42.2% Caucasian, 18.7% African American, 26.4% Hispanic |

| Assessment Tool | Health Behavior in School Aged Children; previous piloting and validation data not reported; 2 items to assess perpetration in the past couple of months (Cronbach’s α = .83). |

| CB criteria | Endorsing one or more behaviors “at least once or twice in the past couple of months” |

| CB Prevalence | Bully: 8.9% |

Maryland public school district study, 2006

Bevans et al., 201351

| CB prevalence main study objective | No | |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying | |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 29 | |

| Sample | 17,198 middle and high school students from a public school district (31 schools total) in Maryland assessed in Nov/Dec 2006 | |

| Middle School | High School | |

| Age not reported; 50.1% female; 60.8% Caucasian, 19.4% African American, 4.5% Hispanic, 3.5% Asian, 11.8% Other | Age not reported; 49.9% female, 69.6% Caucasian, 14.7% African American, 4.0% Hispanic, 3.6% Asian, 7.8% Other | |

| Assessment Tool | Modified version (not previously piloted or validated) of the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire; 1-item: “within the last month, has someone repeatedly tried to hurt you or make you feel bad by emailing/e-messaging you or posting a blog about you on the internet (MySpace)” | |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response to cyberbullying item | |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: 9.02% | |

Bradshaw et al., 201352

| CB prevalence main study objective | No | |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying | |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 27 | |

| Sample | 11,408 middle and 5,790 high school students from a public school district (31 schools total) in Maryland assessed in Nov/Dec 2006 | |

| Middle School | High School | |

| Age not reported; 50.1% female; 60.8% Caucasian, 19.4% African American, 4.5% Hispanic, 3.5% Asian, 11.8% Other | Age not reported; 49.9% female, 69.6% Caucasian, 14.7% African American, 4.0% Hispanic, 3.6% Asian, 7.8% Other | |

| Assessment Tool | Modified version (not previously piloted or validated) of the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire; 1-item: “within the last month, has someone repeatedly tried to hurt you or make you feel bad by emailing/e-messaging you or posting a blog about you on the internet (MySpace)” | |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response | |

| CB Prevalence | Middle School | High Schoo4 |

| Victim: 7.95% | 11.14% | |

Maryland public school district study, 2012

Bradshaw et al., 201553

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Electronic bullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 32 |

| Sample | 24,620 high school students from 52 Maryland high schools assessed in spring 2012 |

| Demographics | M age = 15.98, SD = 1.32; 48.5% female; 45.4% Caucasian, 33.6% African American, 4.5% Hispanic, 4.3% Asian, 9.0% Other |

| Assessment Tool | Modified version of authors’ previous measures;1-item: “within the last month, has someone repeatedly tried to hurt you or make you feel bad by emailing, e-messaging, texting or posting a something bad on the internet (Facebook)” |

| CB criteria | “Yes” response |

| CB Prevalence | Victim: Female 7.5%, Male 4.3% |

Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 201554

| CB prevalence main study objective | No |

| Term Used | Cyberbullying |

| QRT Score (of 42 possible points) | 26 |

| Sample | 28,104 adolescents from 58 high schools in Maryland assessed in spring 2012. |