Abstract

Introduction

Lack of adequate knowledge poses a barrier in the provision of appropriate treatment and care of epileptic patients within the community. The purpose of this study was to determine the knowledge and attitude of community dwellers to epilepsy and its treatment.

Methods

A cross section population survey was conducted in urban and rural Mukono, district, central Uganda. Adult respondents through multistage stratified sampling were interviewed about selected aspects of epilepsy knowledge, attitudes and perception using a pretested structured questionnaire.

Results

Ninety-one percent of the study respondents had heard or read about epilepsy or knew someone who had epilepsy and had seen someone having a seizure. Thirty seven percent of the respondents did not know the cause of epilepsy, while 29% cited genetic causes. About seventeen percent of the subjects believed that epilepsy is contagious. Only 5.6% (21/377) of respondents would take a patient with epilepsy to hospital for treatment.

Conclusion

Adults in Mukono are very acquainted with epilepsy but have many erroneous beliefs about the condition. Negative attitudes are pervasive within communities in Uganda. The National Epilepsy awareness programs need to clarify the purported modes of transmission of epilepsy, available treatment options and care offered during epileptic seizures during community sensitizations in our settings.

Keywords: epilepsy, knowledge, attitudes, practices, Africa

1.0 Introduction

Epilepsy is the most common chronic brain disorder globally and affects people of all ages. It is estimated that more than 70 million people worldwide and 80% of them live in developing countries [1, 2]. It is estimated that about three fourths of people with epilepsy in developing countries do not get the treatment they need[1]. Furthermore, people with epilepsy and their families frequently suffer from stigma and discrimination from their communities.

A recent population study done in 5 African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Ghana, South Africa) showed a higher prevalence of epilepsy ranging between 7 and 15 per 1000 people. Study results show that Iganga district, in Eastern Uganda, the prevalence of epilepsy was 10.3 per 1000 people [3].

Epilepsy has been found to have a high preponderance in onchocerchiasis endemic areas with rates as high as 15–20 cases per 1000 people in Kabarole and Nebbi districts within Uganda [5, 6]. Epilepsy may be secondary to neurological sequelae of viral, bacterial and other parasitic infections (malaria and onchocerciasis) during and beyond childhood [7]. Having proper knowledge and attitudes are important agents’ in the provision of adequate care of epilepsy subjects. This also influences the perceptions and attitudes of communities towards epilepsy subjects and their families. Within communities, discriminations this might impede the provision of adequate care and also increase stigma. Despite advancements in treatment, diagnosis and care of epileptic individuals proper treatment has been limited by: lack of adequate knowledge, associated beliefs and attitudes among the community dwellers. [5, 8–11]. These perceptions and apprehensions vary by country and social context and may limit the implementation of individual or collective strategies to improve the quality of life of people living with epilepsy [12–14].

Community ignorance and misunderstanding about epilepsy, combined with the economic and financial barriers to availability of treatment in developing countries, plays an important role in preventing treatment becoming available to millions of people in developing countries [15, 16]. The main objective of this study was to provide baseline data of the public knowledge, attitudes and practice towards epilepsy in the Mukono district.

2.0 Methods

The cross sectional study was conducted within urban and rural Mukono, with Mukono town council as urban and Kojja sub-county as rural.

This was part of an ongoing population survey on the prevalence and incidence of neurological diseases in Mukono district supported by the U.S. National Institute of Heath-funded Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) program.

During patient recruitment, face to face interviews were conducted between August and November 2014. Multistage stratified sampling technique was used as described below. At the sub-county level, urban Mukono Town Council (TC) was randomly selected and Kojja sub – county (rural) in Mukono district. Mapping of the selected urban and rural areas was based on the Uganda Population and Housing census where 11,373 and 13930 households were identified in Mukono TC and Ntenjeru respectively. The sampling frame was all households in these areas. Systematic sampling was used to select households in each village to total 2000 in the urban area and 2200 in the rural area that would participate in the large population survey. One adult, randomly selected from each household was approached and written consent provided to participate in the study. The selected households were visited by the research team. The randomly selected participant was informed about the research and the intended use of the information obtained.

Consented participants were taken through a pre-tested screening questionnaire and those having symptoms suggesting neurological diseases were presented to the selected health facility the following morning from where they were further evaluated by a team of neurologists. Blood pressure and anthropometric measurements were taken for each participant. Out of the 1500 participants in the urban area and 1500 in the rural area, systematic sampling was used to select 177 and 200 participants from the urban and rural areas, respectively, to be interviewed on selected aspects of epilepsy knowledge, attitudes and perception. The study was conducted from August 2014 to December 2014.

2.1 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Makerere University College of Health Sciences’ School of Medicine review board and ethics committee Ref number 2013–145 and Uganda National Council of Science and Technology Ref Number. HS1551. Written informed consent was obtained before enrolling the participants into the study.

2.2 Questionnaire

A 12 item pretested questionnaire, back translated to English was used for the interview (Table A1). The Luganda study questionnaire was administered by the team of neurologists. This questionnaire was adapted from other questionnaires for epilepsy surveys that had been done elsewhere: Tanzania, Nigeria and Zambia[17–19]. The questionnaire was divided into two portions; the first documented the socio-demographic data of the respondents including the age, sex and marital status. The second part contained questions which were used to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and practice towards epilepsy. These questions included; knowledge on whether the patient had read or heard about the disease, or knew someone who had the disease, the cause of epilepsy, whether epilepsy was contagious. For their attitudes and understanding of the condition, the questionnaire evaluated whether respondents could allow their children to marry or associate with patients with epilepsy, whether epilepsy hindered patients from being employed in jobs normally like others, whether epilepsy was considered as a form of madness or insanity and the preferred treatment options. Most of the questions were simple open-ended questions requiring ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses.

2.3 Data analysis

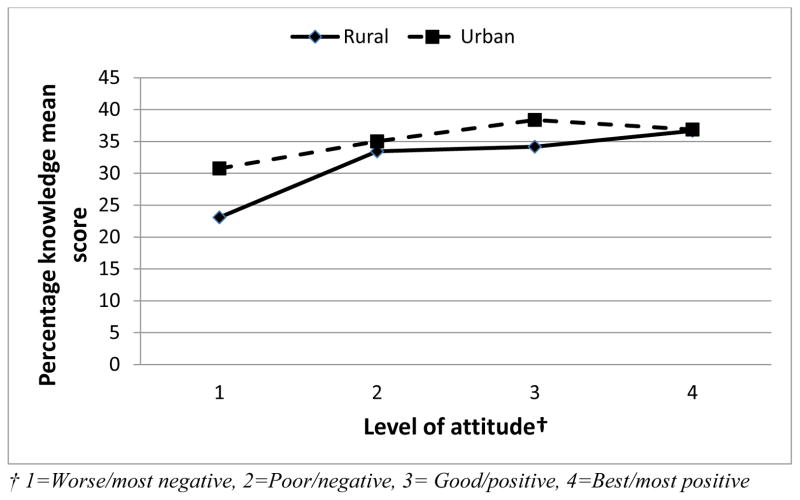

Descriptive statistics of mean, frequency, and percentages were used to summarize data on socio-demographic variables and epilepsy knowledge and attitude. In order to assess the overall distribution for and factors associated with knowledge of epilepsy disease, a percentage score was generated. First, a score 1 was assigned for those giving correct answers or having some knowledge about the epilepsy disease and 0 if otherwise. Then a total was obtained from which a percentage score was calculated. Individuals with higher percentage values above the mean percentage score were considered as having a good knowledge towards the disease. In a similar way, a total score for the attitude was generated, first by assigning a 1 to those with positive attitude and 0 for those with negative attitude. Those who did not know were given no score. Only three attitude variables for which data existed were considered (See Figure A1). A categorical variable for attitude depending on the total score was then generated as follows: 0/3 (worse/most negative), 1/3 (poor/negative), 2/3 (good/positive) and 3/3 (best/most positive).

The distribution for the percentage knowledge score was fairly normal and therefore mean percentage scores were compared using T-test and ANOVAs as appropriate. Linear regression was then fitted for the associated factors. For attitude, only four data points for percentage score existed at 0%, 33.3%, 66.7% and 100%. So an ordinal categorical variable with 4 levels as described above was generated and then a chi-square for trend test used to determine the associated factors. All tests of hypothesis were two tailed with a level of significance at 0.05. All statistical analysis was performed using STATA software version 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

3.0 Results

A total of 377 adults were enrolled to participate in this study with 177 (47%) from the urban settings. Sixty eight percent (260/377) were women with a median age (IQR) of 34 (26 – 48) years. About thirty three percent of the participants were aged between 25 – 34 years.

3.1 Knowledge on epilepsy

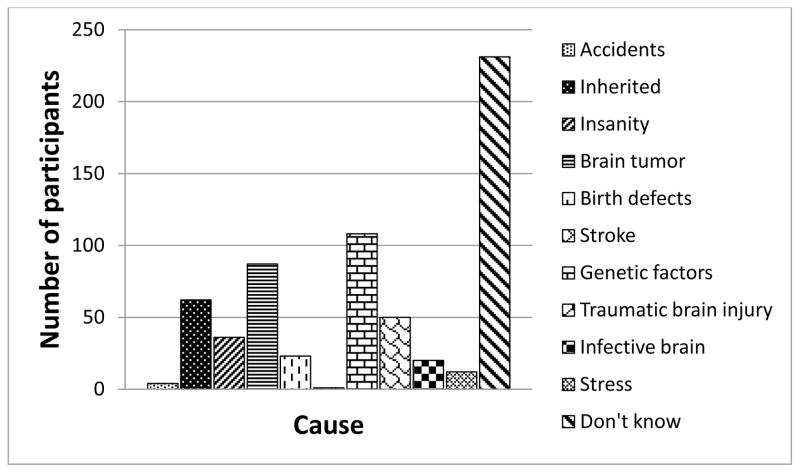

Among the study participants 92% (345/377) reported that they knew the disease called epilepsy. None of the study participants had learnt about epilepsy from health workers or medical doctors (Table 1). A minority attributed epilepsy with insanity (9.6%). About 17% of the study participants knew that epilepsy was contagious, while 39.8% and 30.2% of the study participants thought that it’s a neurological and mental illness respectively. Regarding the causes of epilepsy, the majority did not know the cause of epilepsy (61.3%). (Figure 1)

Table 1.

Knowledge of epilepsy disease (N=377)

| Study question | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Knows the disease called epilepsy | Yes | 345 (91.5) |

| If yes, source of epilepsy knowledge | By mass media | 10 (2.9) |

| Family | 60 (17.4) | |

| Friends | 177 (51.3) | |

| Doctors | 0 (0) | |

| Don’t know | 98 (28.4) | |

| Knows or ever known anyone with epilepsy | Yes | 331 (87.8) |

| Ever seen anyone having an epileptic seizure | Yes | 320 (84.9) |

| What sort of disease is epilepsy* | ||

| Neurological | Yes | 150 (32.3) |

| Mental illness | Yes | 114 (24.5) |

| Contagious | Yes | 64 (13.77.0) |

| Hereditary | Yes | 137 (29.5) |

| Treatment for epilepsy | Specific drugs | 200 (53.1) |

| Surgery | 2 (0.5) | |

| Other | 20 (5.3) | |

| Don’t know | 155 (41.1) | |

| Thinks epilepsy is curable | Yes | 156 (41.4) |

| Would object to having own children associate with persons who had sometimes epileptic seizures in school or in a playground | Yes | 72 (19.1) |

| Would object to a person with epilepsy marrying a close relative | Yes | 157 (41.6) |

| Thinks persons with epilepsy should have children | Yes | 313 (83.0) |

N=465

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution for causes of epilepsy

3.2 Attitudes

About 58% of the respondents agreed to accept someone with epilepsy as a family member through marriage of a close family member. The majority of the subjects (83%) agreed that people with epilepsy can have children. About 19.1% (72/377) would object to having their children associate with persons who have had seizures in school or playground.

3.3 Practice findings

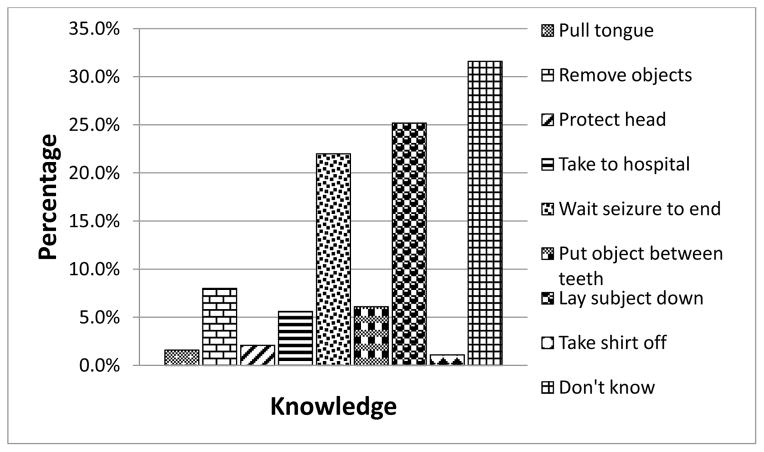

However, 31.6% did not know what to do in case they witnessed a person having a seizure. In case of seizures, only 5.6% of the study respondents would take the patient to hospital. Nearly two percent (6/377) would pull the tongue, while 6.1% (23/377) of the respondents would put an object between the teeth. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution for knowledge of how one would attend to person with seizure

3.4 Associations with knowledge for epilepsy

Generally, there was poor knowledge and perception for epilepsy disease with a median score of 32% (IQR: 24% to 36%) and 99% (373/377) scoring below 50%. Overall, about rural residency participants had scored lowly in knowledge and participants who were discriminatory also had significantly lower knowledge with p-value < 0.001 (Figure 3). Residency was significantly associated with knowledge; p – value =0.003. Age and sex were not significantly associated with knowledge (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Showing distribution for percentage knowledge score by levels of attitude towards epilepsy disease

Table 2.

Relationship between the percentage knowledge score and the study variables

| N | Mean percentage score for knowledge (SD) | P† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 377 | 35.13 (8.51) | ||

| Level of attitude | Worse/most negative | 5 | 26.15 (6.88) | <0.001 |

| Discriminatory | 78 | 34.02 (8.06) | ||

| Poor/negative Low | 143 | 35.58 (8.46) | ||

| Good/positive Moderate | 139 | 36.80 (7.48) | ||

| Best/most positive High | 12 | 21.15 (8.91) | ||

| Don’t know | ||||

| Residence | Rural | 200 | 33.90 (8.84) | 0.003 |

| Urban | 177 | 36.51 (7.92) | ||

| Age in years | <25 | 74 | 33.73 (8.93) | 0.267 |

| 25 – 34 | 125 | 35.54 (7.96) | ||

| 35 – 44 | 66 | 36.42 (7.85) | ||

| > 44 | 112 | 34.82 (9.13) | ||

| Sex | Male | 123 | 34.71 (8.91) | 0.509 |

| Female | 254 | 35.33 (8.51) | ||

comparing means using one way ANOVAs and t-test

Levels of attitude and urban residency were significantly associated with knowledge regarding epilepsy (Table 3). There was no interaction effect between the level of attitude and the residence (likelihood ratio test: p=0.215)

Table 3.

Factors associated with knowledge of epilepsy using linear regression. Linear regression model results for factors associated knowledge for epilepsy disease

| Unadjusted effects

|

Adjusted effects

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model coefficient (95% CI) | P | Model coefficient (95% CI) | P | ||

| Level of attitude | Worse/most −ve | Reference | Reference | ||

| Poor/negative | 7.87 (0.59 – 15.15) | 0.034 | 7.93 (0.69 – 15.16) | 0.032 | |

| Good/positive | 9.43 (2.25 – 16.61) | 0.010 | 9.56 (2.42 – 16.70) | 0.009 | |

| Best/most +ve | 10.65 (3.47 – 17.83) | 0.004 | 10.09 (2.93 – 17.24) | 0.006 | |

| Discriminatory | −5.00 (−13.40 – 3.40) | 0.242 | −4.87 (−13.21 – 3.48) | 0.253 | |

| Low | |||||

| Moderate | |||||

| High | |||||

| Don’t know | |||||

| Residence | Rural | Reference | Reference | ||

| Urban | 2.60 (0.89 – 4.31) | 0.003 | 2.02 (0.31 – 3.73) | 0.020 | |

3.5 Associations with attitude towards epilepsy

Of the 365 participants who responded to the attitude questions towards epilepsy, about 77% were positive or most positive towards epilepsy. About half of those from the rural area had good/positive attitude, and more than half of those in urban had best/most positive attitude. Attitude towards epilepsy was significantly better among those in the urban compared to their counterparts in the rural area (p<0.001). Attitude did not significantly differ by age or sex (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with attitude towards epilepsy using a chi-square for trend test

| Level of attitude (N = 365)

|

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worse/most negative N (%) |

Poor/negative N (%) |

Good/positive N (%) |

Best/most positive N (%) |

||

| Overall | 5 (1.37) | 78 (21.37) | 143 (39.18) | 139 (38.08) | |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 3 (1.56) | 49 (25.52) | 95 (49.48) | 45 (23.44) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 2 (1.16) | 29 (16.76) | 48 (27.75) | 94 (54.34) | |

| Age in years | |||||

| <25 | 2 (2.82) | 18 (25.35) | 21 (29.58) | 30 (42.25) | 0.129 |

| 25 – 34 | 0 (0.00) | 24 (19.83) | 48 (39.67) | 49 (50.50) | |

| 35 – 44 | 3 (4.62) | 15 (23.08) | 28 (43.08) | 19 (29.23) | |

| > 44 | 0 (0.00) | 21 (19.44) | 46 (42.59) | 41 (37.96) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1 (0.85) | 28 (23.73) | 47 (39.83) | 42 (35.59) | 0.527 |

| Female | 4 (1.62) | 50 (20.24) | 96 (38.87) | 97 (39.27) | |

Discussion

In spite of the fact that epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders, the study showed that the knowledge about epilepsy was generally poor in this Ugandan community. This finding is similar to other reports from sub – Saharan Africa [18, 20, 21]. The community study participants had limited knowledge about causes and characterisation of epilepsy which is also in agreement with other reports from sub – Saharan Africa [22, 23]. These findings have important implications for identifying and referring people with epilepsy within communities to appropriate care.

4.1 Knowledge regarding epilepsy

Majority of the study participants reported having witnessed or knew someone with epilepsy. However, overall the actual knowledge about epilepsy was poor among the study participants. The vast majority did not know any of the causes of epilepsy. The leading cause cited by the participants was inheritance. This result is poorer than earlier studies in similar African settings on knowledge of epilepsy in the community dwellers in sub Saharan Africa. In contrast to earlier studies, the study populations are different. Earlier studies have mostly been conducted within specific community groups such as teachers, traditional healers, university students, literate urban population and secondary school students [17, 21, 24]. This might explain the poorer knowledge of epilepsy in our populations. However, the survey shared some similarities with studies conducted in Tanzania and Senegal [25, 26].. A higher proportion of respondents 80% in Uganda had witnessed a seizure compared to about two-thirds (67.1% and 66.1%) in Tanzania and Senegal respectively. In Uganda a smaller proportion of respondents 17.0% believed that epilepsy was contagious compared to 40.6% and 35.1% in Tanzania and Senegal respectively. Our study comprised of both rural and urban settings, compared to the Tanzanian study which was rural while the Senegal study was urban. The different locations, awareness campaigns and timings might have played a role in increasing knowledge among the respondents in Uganda.

Whereas previous studies on knowledge, attitudes and practices towards epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa have shown that epilepsy is perceived to be caused by “supernatural” or “spiritual” factors, none of the study participants cited the role of supernatural or spiritual factors as causation of epilepsy. However, 5% of the study participants suggested that native medicine, herbal remedies or spiritual intervention could play an important role in the treatment of patients with epilepsy. A more detailed focus group discussion with the study participants would probably have unmasked these hidden beliefs.

4.2 Attitudes regarding epilepsy

Regarding the attitudes towards epilepsy, stigma and social ostracism were evident. The proportion of survey respondents objecting to a person with epilepsy marrying a close relative, are similar to those from some other sub Saharan African countries [26, 27] but lower compared to an earlier study from Cameroon [16]. Interestingly, there were no differences in response to this question related to survey respondent demographics among the study participants. This could reflect the fact that attitudes are widely shared and perhaps have not changed much in recent years.

4.3 Practice regarding epilepsy

A third of Ugandan study population did not know what to do in scenarios when faced with a person having seizures. There is a need to develop approaches to combat stigma and discrimination against people with epilepsy in our setting. Strengthening local advocacy groups or organisations which support people with epilepsy could play an important role to counter negative stereotypes [28, 29]. Increasing knowledge in the general population regarding the nature of epilepsy, possible treatments available, and nearby health centre facilities offering needed medical care might also help. Finally improving the treatment and care of people suffering from epilepsy by providing readily available medical treatments could improve seizure control, reduce epilepsy burden and improve quality of life among those with epilepsy.

4.4 Strengths and limitations

The studied population is representative of the general population, including the rural and urban settings in Uganda. Other strengths include use of a standardised instrument to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and practice. Limitations include use of cross-sectional design and the fact that self reported practice may not match actual behaviours. Majority of the study participants were female, hence might not totally represent the beliefs and attitudes of male community dwellers. We did not include focus group discussions in this study to further explore the beliefs and attitudes of the study participants. This could have given the study participants to freely express themselves without favourably talking about western medicine.

4.5 Conclusion

Knowledge regarding epilepsy among community respondents is limited in Uganda. Awareness and informational campaigns are needed to help change the perception of epilepsy and maximise the chance that people with epilepsy will present for treatment. The Epilepsy Support Association of Uganda in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, health professional organisations, needs a concerted effort to address this.

Supplementary Material

Highlights for review.

We describe knowledge on epilepsy

Stigma and care for subjects with epilepsy still remains a big challenge in Uganda. Inadequate knowledge impacts on care

Yet pProper knowledge would improves care

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institute of Health under MEPI – Neurology linked award number R25NS080968. We thank Doreen Birungi for the support and guidance. We also thank our survey subjects for participating in this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author’s contributions

MK, ED, JK and MNK collected data during the survey; IM and EK performed data analyses; MS, SP, AF and EK designed the study; IM, MK, JK, and MS wrote the paper. MS, AF, SP and EK revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mark Kaddumukasa, Email: kaddumark@yahoo.co.uk.

Angelina Kakooza, Email: Angelina-Kakooza@yahoo.co.uk.

James Kayima, Email: jkkayima@gmail.com.

Martin N. Kaddumukasa, Email: kaddumart@yahoo.com.

Edward Ddumba, Email: ddumbaentamuezala@gmail.com.

Levi Mugenyi, Email: lmugenyi005@gmail.com.

Anthony Furlan, Email: Anthony.Furlan@UHhospitals.org.

Samden Lhatoo, Email: Samden.Lhatoo@UHhospitals.org.

Martha Sajatovic, Email: Martha.Sajatovic@UHhospitals.org.

Elly Katabira, Email: katabira@imul.com.

References

- 1.WHO. Epilepsy. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Sander JW, Newton CR. Estimation of the burden of active and life-time epilepsy: a meta-analytic approach. Epilepsia. 2010;51:883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngugi AK, Bottomley C, Kleinschmidt I, Wagner RG, Kakooza-Mwesige A, Ae-Ngibise K, Owusu-Agyei S, Masanja H, Kamuyu G, Odhiambo R, Chengo E, Sander JW, Newton CR. Prevalence of active convulsive epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa and associated risk factors: cross-sectional and case-control studies. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:253–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser C, Asaba G, Leichsenring M, Kabagambe G. High incidence of epilepsy related to onchocerciasis in West Uganda. Epilepsy Res. 1998;30:247–51. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baskind R, Birbeck GL. Epilepsy-associated stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: the social landscape of a disease. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Epilepsy in the African Region. Geneva: WHO; 2004. Epilepsy in the WHO African region: bridging the gap? pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ovuga E, Kipp W, Mungherera M, Kasoro S. Epilepsy and retarded growth in a hyperendemic focus of onchocerciasis in rural western Uganda. East Afr Med J. 1992;69:554–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watts AE. A model for managing epilepsy in a rural community in Africa. BMJ. 1989;298:805–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mushi D, Hunter E, Mtuya C, Mshana G, Aris E, Walker R. Social-cultural aspects of epilepsy in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania: knowledge and experience among patients and carers. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;20:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkler AS, Mayer M, Schnaitmann S, Ombay M, Mathias B, Schmutzhard E, Jilek-Aall L. Belief systems of epilepsy and attitudes toward people living with epilepsy in a rural community of northern Tanzania. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mbuba CK, Ngugi AK, Newton CR, Carter JA. The epilepsy treatment gap in developing countries: a systematic review of the magnitude, causes, and intervention strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1491–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mbuba CK, Newton CR. Packages of care for epilepsy in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baskind R, Birbeck G. Epilepsy care in Zambia: a study of traditional healers. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1121–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.03505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bener A, al-Marzooqi FH, Sztriha L. Public awareness and attitudes towards epilepsy in the United Arab Emirates. Seizure. 1998;7:219–22. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(98)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burneo JG, Tellez-Zenteno J, Wiebe S. Understanding the burden of epilepsy in Latin America: a systematic review of its prevalence and incidence. Epilepsy Res. 2005;66:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bain LE, Awah PK, Takougang I, Sigal Y, Ajime TT. Public awareness, knowledge and practice relating to epilepsy amongst adult residents in rural Cameroon--case study of the Fundong health district. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:32. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.32.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ezeala-Adikaibe BA, Achor JU, Onwukwe J, Ekenze OS, Onwuekwe IO, Chukwu O, Onyia H, Ihekwaba M, Obu C. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards epilepsy among secondary school students in Enugu, southeast Nigeria. Seizure. 2013;22:299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pupillo E, Vitelli E, Messina P, Beghi E. Knowledge and attitudes towards epilepsy in Zambia: a questionnaire survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;34:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mushi D, Burton K, Mtuya C, Gona JK, Walker R, Newton CR. Perceptions, social life, treatment and education gap of Tanzanian children with epilepsy: a community-based study. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23:224–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiga Y, Albakaye M, Diallo LL, Traore B, Cissoko Y, Hassane S, Diakite S, Clare McCaughey K, Kissani N, Diaconu V, Buch D, Kayentoa K, Carmant L. Current beliefs and attitudes regarding epilepsy in Mali. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;33:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akpan MU, Ikpeme EE, Utuk EO. Teachers’ knowledge and attitudes towards seizure disorder: a comparative study of urban and rural school teachers in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16:365–70. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.113465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seneviratne U, Rajapakse P, Pathirana R, Seetha T. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of epilepsy in rural Sri Lanka. Seizure. 2002;11:40–3. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2001.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mugumbate J, Mushonga J. Myths, perceptions, and incorrect knowledge surrounding epilepsy in rural Zimbabwe: a study of the villagers in Buhera District. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:144–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustapha AF, Odu OO, Akande O. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of epilepsy among secondary school teachers in Osogbo South-West Nigeria: a community based study. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16:12–8. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.106709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rwiza HT, Matuja WB, Kilonzo GP, Haule J, Mbena P, Mwang’ombola R, Jilek-Aall L. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward epilepsy among rural Tanzanian residents. Epilepsia. 1993;34:1017–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ndoye NF, Sow AD, Diop AG, Sessouma B, Sene-Diouf F, Boissy L, Wone I, Toure K, Ndiaye M, Ndiaye P, de Boer H, Engel J, Mandlhate C, Meinardi H, Prilipko L, Sander JW. Prevalence of epilepsy its treatment gap and knowledge, attitude and practice of its population in sub-urban Senegal an ILAE/IBE/WHO study. Seizure. 2005;14:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghanean H, Nojomi M, Jacobsson L. Public awareness and attitudes towards epilepsy in Tehran, Iran. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:21618. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandstra NF, Camfield CS, Camfield PR. Stigma of epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:436–40. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100009082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacoby A, Gorry J, Gamble C, Baker GA. Public knowledge, private grief: a study of public attitudes to epilepsy in the United Kingdom and implications for stigma. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1405–15. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.