Abstract

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) achieve an intermediate or “primed” state of activation following stimulation with certain agonists. Primed PMN have enhanced responsiveness to subsequent stimuli, which can be beneficial in eliminating microbes but may cause host tissue damage in certain disease contexts including sepsis. As PMN priming by TLR4 agonists is well-described, we hypothesized that ligation of TLR2/1 or TLR2/6 would prime PMN. Surprisingly, PMN from only a subset of donors were primed in response to the TLR2/1 agonist, Pam3CSK4, although PMN from all donors were primed by the TLR2/6 agonist, FSL-1. Priming responses included generation of intracellular and extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), MAPK phosphorylation, integrin activation, secondary granule exocytosis, and cytokine secretion. Genotyping studies revealed that PMN responsiveness to Pam3CSK4 was enhanced by a common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in TLR1 (rs5743618). Notably, PMN from donors with the SNP had higher surface levels of TLR1, and were demonstrated to have enhanced association of TLR1 with the ER chaperone gp96. We analyzed TLR1 genotypes in a pediatric sepsis database and found that patients with sepsis or septic shock who had a positive blood culture and were homozygous for the SNP associated with neutrophil priming had prolonged pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) length of stay. We conclude that this TLR1 SNP leads to excessive PMN priming in response to cell stimulation. Based on our finding that septic children with this SNP had longer PICU stays, we speculate that this SNP results in hyperinflammation in diseases such as sepsis.

Introduction

PMN (or neutrophils), essential innate immune cells, recognize danger signals through receptors on their surface including TLRs. Upon receptor ligation, PMN may undergo priming, a sequential activation process involving shape change, integrin activation, limited granule exocytosis, and low-level ROS generation. Some of these ROS are formed in intracellular endocytic compartments and are required for activation of intracellular signaling cascades that permit a greatly enhanced cellular response upon exposure to a secondary stimulus (1, 2).

PMN priming was initially perceived as a beneficial phenomenon as primed PMN undergo further activation at sites of infection and are very effective at killing pathogens. However, there is a growing recognition that PMN priming can also be detrimental as activated PMN can potentiate hyperinflammation and subsequent host tissue damage, a leading cause of mortality in patients with sepsis (3).

Our laboratory has extensively investigated PMN priming by endotoxin (1) and TNF-α (4), ligands for TLR4 and the TNF receptors, respectively. However, there is limited literature on PMN priming through other pattern recognition receptors including TLR2, which has been implicated in several diseases including tuberculosis (5), leprosy (6, 7), and sepsis (8). TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 heterodimers recognize several stimuli, including triacylated and diacylated lipopeptides, respectively, from bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi. TLR2, TLR1, and TLR6 are expressed on PMN (9) and a limited number of studies have reported that TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 agonists induce PMN activity. In 1990, Seifert et al. published that PMN exposed to 30–200 μg/ml Pam3CSK4, a specific TLR2/1 agonist, released lysozyme and generated superoxide anion as measured by the reduction of ferricytochrome c (10). Sabroe et al. expanded on this finding and demonstrated that 10–10,000 ng/ml Pam3CSK4 increased CD11b surface expression and induced IL-8 secretion (11). Similarly, PMN treated with 10 ng/ml macrophage activating lipopeptide-2, a TLR2/6 agonist, or 1–10 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 underwent shape change, displayed enhanced phagocytic capacity, and secreted IL-8 and MIP-1β (12). Finally, Pam3CSK4 and macrophage activating lipopeptide-2 were shown to delay PMN apoptosis by Annexin V staining (13). Notably, these studies reported no differences in signaling pathways downstream of TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 (14), nor any significant donor variation in TLR2 ligand-induced cellular responses.

Our laboratory became interested in neutrophil responses to TLR2 agonists after finding complex and unexpected interactions between TLR2 ligation and the NADPH oxidase 2 using a murine model of systemic inflammation elicited by injection of a TLR2 agonist (15, 16). In the current study, we sought to further define human PMN priming responses to TLR2 ligands in vitro/ex vivo. In contrast to previously published studies, we observed that FSL-1, a TLR2/6 ligand, primes PMN isolated from all donors, but that Pam3CSK4 primes PMN isolated from one subset of donors to a significantly greater extent than PMN isolated from another subset of donors. PMN priming was evidenced by ROS generation, MAPK activation, integrin activation, secondary granule exocytosis, and cytokine release. We determined that the disparity in Pam3CSK4 priming responses correlates with a common SNP in TLR1 (rs5743618). PMN from donors with at least one SNP-containing allele have enhanced TLR1 surface expression and prime robustly in response to Pam3CSK4, suggesting that this SNP affects TLR1 trafficking and signaling. As a mechanism for this alteration in trafficking, we demonstrated by immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting that PMNs with the SNP displayed enhanced association between TLR1 and the ER chaperone gp96, previously demonstrated to have a role in TLR trafficking (17, 18). Importantly, this SNP has previously been shown to increase the risk of circulatory dysfunction (8) and mortality (19) in adult patients with sepsis. We subsequently analyzed the TLR1 genotypes from a pediatric sepsis database and demonstrated that patients with the TLR1 SNP had significantly longer stays in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. We speculate that sepsis patients with this TLR1 SNP demonstrate excessive PMN priming and altered monocyte activation putting them at risk of hyperinflammation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Dextran was purchased from Pharmacosmos (Holboek, Denmark) and Hypaque-Ficoll from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), and RPMI 1640 were obtained from Mediatech (Manassas, VA, USA). Human serum albumin was from Talecric Biotherapeutics (Durham, NC, USA). Bovine serum albumin, dextrose, and BS3 were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). FSL-1 and Pam3CSK4 were obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA), recombinant TNF-α was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA), and fMLF was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Lucigenin, SOD, and cytochrome c were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Amplex UltraRed, OxyBURST® Green BSA, and protein A and G dynabead immunoprecipitation kits were from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). Anti-CD11b was obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA), anti-active CD11b (clone CBRM1/5) from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD66b from AbD Serotec (Raleigh, NC), and anti-CD63 from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained in The University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA, USA). Anti-TLR1-APC was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-TLR6 (CD286)-PE from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-TLR2 (CD282)-FITC from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-TLR1, anti-TLR2, and anti-gp96 for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA) and MAPK antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Secondary antibodies for immunoblotting and flow cytometry were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) and Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA), respectively. ELISA antibodies (including streptavidin-HRP) were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) with the exception of the IL-8 antibodies which were from BD (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Additional reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Isolation and stimulation of human PMN and monocytes

Human PMN and monocytes were isolated from heparin-treated venous blood by standard techniques and PMN were purified by sequential dextran sedimentation, Hypaque-Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation, and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes (20). PMN were resuspended in HBSS with calcium and magnesium with 1% human serum albumin and 0.1% dextrose unless otherwise noted and were used for experimentation within 10 min of isolation. Using this method, PMN purity was > 95%. Following Hypaque-Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were removed and plated in RPMI 1640 with 10% autologous serum at a concentration of 3 × 106 cells/ml. Following 1 h incubation at 37°C, cells were washed three times with DPBS to remove lymphocytes before fresh RPMI 1640 with 10% autologous serum (with or without a stimulus) was added to wells containing adherent monocytes. Unless otherwise stated, cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml FSL-1, 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4, or 1 ng/ml TNF-α.

Measurements of NADPH oxidase activity

For lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence (LUC-CL) assays, 200 μl of suspension containing a final concentration of 2.5 × 106 PMN/ml, 100 μM lucigenin, and stimulus was added per well of a 96-well plate. Each condition was performed in triplicate wells. For priming experiments, fMLF (1 μM final concentration) was injected into the wells after 30 min. Chemiluminescence was quantitated as relative light units (RLU) using a kinetic assay with readings every 30 sec or 1 min for 0–60 min on a FLUOstar Omega or CLARIOstar (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA).

Amplex UltraRed assays for quantitation of H2O2 generation were performed by adding 100 μl of a PMN suspension containing 1 × 107 PMN/ml to duplicate wells of a 96 well plate with Amplex UltraRed (100 μM final concentration) and excess Streptavidin-HRP. PMN were stimulated as described immediately prior to loading. NOX2 activity was expressed as relative fluorescence units with readings every 60 sec for 90 cycles on a FLUOstar Omega. In some wells, fMLF was injected at cycle 30. For each plate, an H2O2 standard curve (0.5–10 μM) was performed and the amount of H2O2 (μM) generated was extrapolated. Our lab has previously tested the capacity of Amplex UltraRed to be taken up into endosomes upon cellular stimulation; thus, this assay can be used to measure both intracellular and extracellular H2O2 generation (21). For an additional specific measurement of intracellular, endocytic ROS, freshly isolated PMN were stimulated for 0 or 60 min in suspension at 37°C in the presence of OxyBURST® green BSA (100 ug/ml). At the specified time points, cells were immediately placed on ice and analyzed for fluorescence on a BD LSR II (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA).

Extracellular superoxide generation was measured by ferricytochrome c reduction. 4.5 × 105 PMN in the presence of 40 μM cytochrome c were added to each well of a 96-well plate in a final volume of 200 μl. PMN were stimulated immediately prior to loading. SOD (50 μg/ml) was added to a duplicate set of wells. Readings were taken every 60 sec for 30 cycles, fMLF was added to the wells, and readings were taken for an additional 30 cycles on a FLUOstar Omega. The total nmol superoxide/ml was calculated as the SOD-inhibitable reduction of cytochrome c.

Flow cytometry

To assess cell surface markers of activation and granule exocytosis, freshly isolated PMN were stimulated for 30 min at 37°C. In a subset of experiments, PMN were treated with 10 μM control (SB 202474) or p38 (SB 203580) inhibitor from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 10 min at room temperature prior to stimulation. Surface expression of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 were assayed in freshly isolated, unstimulated PMN. PMN were centrifuged and resuspended in blocking buffer (PBS with 2% nonfat dry milk and 4% NGS) for 20 min on ice, then incubated in the presence of primary antibodies for 1 h on ice. PMN were centrifuged and resuspended in 150 μl blocking buffer containing FITC-conjugated secondary antibody diluted 1:1000 and incubated on ice for 30 min. PMN were washed with 3 ml ice cold PBS and resuspended in PBS for analysis using a BD FACScan (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA). Neutrophils (>98% purity following isolation) were gated based on FSC and SSC and data were analyzed using FlowJo 7.6.4 software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Analysis of MAPK phosphorylation and total TLR1 by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

PMN (2 × 107/ml) were incubated in the presence of agonist for the specified time points. After incubation, cells were pelleted and lysed in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2% leupeptin/pepstatin A) for 45 min at 4°C. Lysates were centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 7 min at 4°C, placed in tubes with sample buffer, and heated to 103°C for 3 minutes. Samples were resolved in an Any kD™ gel (Biorad) by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with 3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with primary antibodies against phosphorylated or total MAPKs (p38, ERK1/2, or JNK), β-actin, or TLR1. Secondary antibodies were conjugated to HRP or fluorophores and detected by chemiluminescence or fluorescence, respectively. Blots were scanned on an Image Station 400MM Pro (Carestream Health, Inc., Rochester, NY) and bands were quantitated using ImageQuant TL software (Sunnyvale, CA).

PMN and monocyte supernatant collection and cytokine quantification by ELISA

Freshly isolated PMN or monocytes (2.5 × 106/ml) were treated as indicated. PMN were gently tumbled and monocytes were plated at 37°C for 24 h. Following the incubation, PMN were pelleted, and PMN and monocyte supernatants were frozen at −80°C. For cytokine quantification, 96-well NUNC Maxisorp microplates were coated with antibodies against IL-8, IL-6, MCP-1, TNF-α, or IL-1Ra in carbonate buffer (100 mM NaHCO3, 34 mM Na2CO3, pH 9.6) overnight at room temperature. Wells were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA and 5% sucrose for 1 h. Standards and samples (thawed supernatants) were diluted in assay diluent (PBS with 0.1% BSA), loaded into duplicate wells, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Biotinylated antibody against the target cytokine was added and allowed to incubate for 2 h followed by streptavidin-HRP for 20 min. Finally, tetramethylbenzidine was added to the wells for 10–30 min for color development and 0.5M H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction. All incubations were performed at room temperature and wells were rinsed three times with wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) between each step. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured on a FLUOstar Omega.

SNP selection, DNA isolation, and genotyping

The Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) was used to identify SNPs in the exons of TLR1. Only two SNPs were noted to have the frequency we had observed in European/American populations, rs5743618 (S602I) and rs4833095 (N248S). To sequence these SNPs, DNA was extracted from isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from consenting healthy adults using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg, The Netherlands). Primers flanking these SNPs were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The forward and reverse primers for the rs5743618 (S602I) SNP are CCCGGAAAGTTATAGAGGAACC and CATGAAACTGGAGATTTCTTTGG, respectively. The forward and reverse primers for the rs4833095 (N248S) SNP are TTGTGTTCCCCACAAACAAA and CGAACACATCGCTGACAACT, respectively. For both primers, an annealing temperature of 58°C was used. PCR products were sequenced by Functional Biosciences, Inc. (Madison, WI) or the Next Generation Sequencing Core at UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX, USA) as previously described (22).

Annexin V analysis of PMN apoptosis

Freshly isolated PMN were treated at a concentration of 2.5 × 106/ml. PMN were tumbled at 37°C for 24 h. Following this incubation, PMN were pelleted, resuspended in 100 μl of 1X Annexin V Binding Buffer, and immediately placed on melting ice. Following the addition of 5μl Annexin V-FITC and 5 μl PI to each tube, tubes were gently mixed and incubated in the dark for 15 min. 100 μl of 1X Annexin V Binding Buffer was then added to each tube and tubes were analyzed immediately on a BD FACScan. (All buffers and dyes were provided in the Annexin V FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit II from BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA.)

Immunoprecipitation

Five hundred micrograms of post-nuclear supernatant from cells lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Imidazole, 2 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% TX-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2% leupeptin/pepstatin A) was rotated with antibody-conjugated dynabeads for 1 h at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Beads were washed extensively followed by elution of bound proteins. Eluted sample was heated at 70°C for 10 min and immediately used for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described previously to detect immunoprecipitated proteins.

Pediatric septic shock cohort

DNA samples were obtained from a multi-center database of children with septic shock, previously described in detail (23). Children ≤ 10 years of age admitted to the PICU and meeting pediatric-specific consensus criteria for septic shock were eligible for enrollment. After informed consent from parents or legal guardians, serum samples were obtained within 24 hours of initial presentation to the PICU with septic shock. Clinical and laboratory data were collected daily while in the PICU. Mortality was tracked for 28 days after enrollment and organ failure was defined using pediatric specific criteria. PICU length of stay (LOS) and PICU free days were calculated for each patient. PICU free days were calculated by subtracting the actual PICU length of stay from a theoretical maximum stay of 28 days. Patients who died before the 28 observation period and patients who remained in the ICU for > 28 days were assigned zero PICU free days. Thus, a lower number of PICU free days serves as a measure of delayed or lack of recovery from critical illness. PICU LOS measurements are not adjusted for early mortality, therefore in some analyses; patients who died during their ICU course were excluded from the dataset. Complicated course was defined as persistence of two or more organ failures at day 7 of sepsis or 28 day mortality (23).

Statistics

MAPK data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests to compare between treatments at each time point. Additional comparisons of neutrophil functional output and phenotype data were made by Student’s t-tests. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad PRISM 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC). For the sepsis database genotype comparisons analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were conducted to investigate if there were significant differences in continuous clinical outcomes among three genotype groups of GG, GT, and TT. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used for binary outcomes. Bonferroni corrections were used to adjust the effect of multiple comparisons. Student’s t-tests were used to examine if there were significant differences in continuous clinical outcomes between GG and (GT+TT). Stepwise linear and logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate if genotype was significantly associated with continuous or binary clinical outcomes after controlling the confounding effects of gender, age, and race.

Study approval

Neutrophil and monocyte studies were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board for human subjects at The University of Iowa or The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and written informed consent was received from all participants prior to inclusion in the study. The pediatric study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating institution, and written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians prior to inclusion in the study.

Results

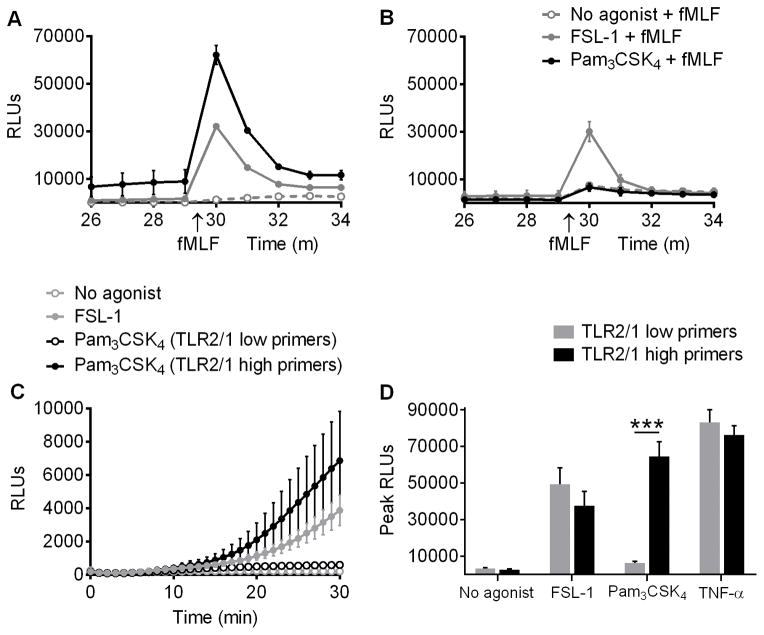

TLR2/1 ligands only elicit priming of the respiratory burst in human PMN from a subset of donors

To explore whether TLR2 agonists prime human PMN, NOX2 activity was evaluated by LUC-CL in PMN treated with no agonist, FSL-1 (a TLR2/6 agonist), Pam3CSK4 (a TLR2/1 agonist), or TNF-α (as a positive control for priming) for 30 min, and then exposed to fMLF as a secondary stimulus. The ROS formed during the 30 min exposure to only the priming stimulus (TLR ligand or TNF-α) are referred to as “direct ROS”, while ROS generated after exposure to the priming and secondary stimuli are referred to as “primed ROS”. Although there were minor differences in magnitude, PMN from all donors generated both direct and primed ROS in response to FSL-1. However, PMN from only half of the donors generated direct and primed ROS following Pam3CSK4 treatment (Figure 1). Donors whose PMN generated a greater than 5-fold increase in ROS by LUC-CL when primed with Pam3CSK4 as compared to control cells will henceforth be referred to as TLR2/1 high primers, while donors whose PMN generated a less than 5-fold increase will be referred to as TLR2/1 low primers. TNF-α, used as a positive control for priming, led to direct (data not shown) and primed (Figure 1D) ROS generation in PMN from all donors.

Figure 1. In contrast to TLR2/6 stimulation, a TLR2/1 agonist primes ROS generation in PMN from only half of donors.

ROS generation was measured by LUC-CL as RLUs in PMN primed with no agonist, 100 ng/ml FSL-1 (a TLR2/6 agonist), or 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 (a TLR2/1 agonist) for 30 min and then stimulated with fMLF. Representative tracings (mean ± SEM of three replicates) for (A) a donor whose PMN primed in response to Pam3CSK4 (TLR2/1 high primer) and (B) a donor whose PMN did not prime in response to Pam3CSK4 (TLR2/1 low primer). (C) Combined donor data (mean ± SEM) showing direct ROS production (priming stimulus only). n ≥ 16 per group. (D) Peak RLUs (mean + SEM) immediately following addition of fMLF after 30 min of priming in TLR2/1 high primers (black bars) and TLR2/1 low primers (gray bars). n ≥ 16 per group. ***p < 0.0001, Students t test.

To determine whether the minimal response observed in the TLR2/1 low primers could be overcome with higher concentrations of ligand, we primed cells from TLR2/1 high and low primers with 0, 1, 3, or 10 μg/ml of Pam3CSK4 for 30 min, added fMLF as a secondary stimulus, and measured ROS generation by LUC-CL. There was a dose-dependent increase in primed ROS generation in both TLR2/1 high and low primers, but the difference between the two groups remained highly significant at all agonist concentrations (Supplemental Figure 1). This argues against the idea that PMN from TLR2/1 low primers merely have a higher threshold dose that is needed to achieve priming responses of similar magnitude to PMN from TLR2/1 high primers. Rather, the data suggest that there is an intrinsic difference in the two subgroups of donors that determines their responsiveness to TLR2/1 agonists.

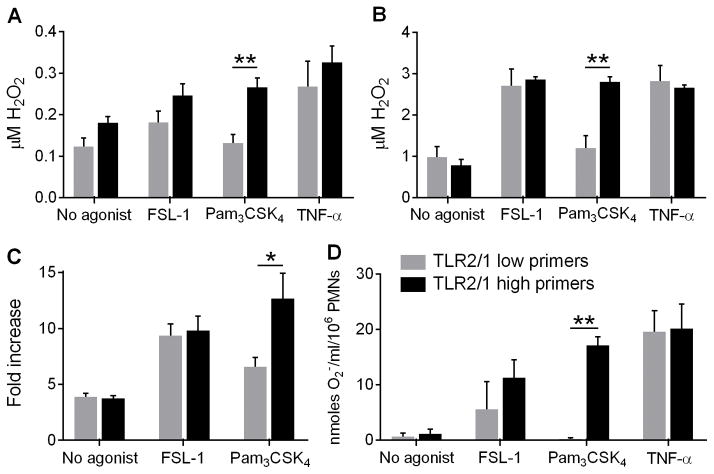

To verify these initial LUC-CL findings, and to comprehensively and quantitatively evaluate oxidant generation elicited by Pam3CSK4 or FSL-1 priming, we measured ROS generation by several additional methods. Intra- and extra-cellular H2O2 generation was measured quantitatively (Amplex Ultra Red) and confirmed that FSL-1 led to direct (Figure 2A) and primed (Figure 2B) H2O2 generation in cells from all donors, whereas Pam3CSK4 induced significantly greater direct and primed H2O2 generation in PMN from TLR2/1 high primers than low primers. In fact, TLR2/1 low primers stimulated with Pam3CSK4 did not have greater H2O2 generation than under unstimulated conditions. The division of the donors into TLR2/1 high and low primers using this quantitative methodology was identical to the division observed using the non-quantitative LUC-CL assay.

Figure 2. Pam3CSK4 induces significantly greater direct and primed ROS production by TLR2/1 high primers than TLR2/1 low primers.

(A) Direct and (B) primed generation of H2O2 measured by Amplex UltraRed in response to no agonist, 100 ng/ml FSL-1, 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4, or 1 ng/ml TNF-α. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 3 per group. **p < 0.01. TLR2/1 low primers did not generate H2O2 above no agonist levels when stimulated with Pam3CSK4. (C) Intracellular ROS generation was determined by OxyBURST® green. Mean + SEM, n = 6 per group. *p < 0.05. (D) Primed generation of superoxide measured by SOD-inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome c. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 2 per group. **p < 0.01. P values were calculated by Student’s t tests between TLR2/1 low primers and TLR2/1 high primers.

As we have previously demonstrated that intracellular, direct ROS serve as necessary signaling mediators for PMN priming (2), we measured intracellular endocytic ROS generation (OxyBURST® green BSA). Significantly, Pam3CSK4 led to greater intracellular ROS generation in PMN from TLR2/1 high primers than TLR2/1 low primers, while PMN from all donors had the same responsiveness to FSL-1 (Figure 2C). No extracellular superoxide generation was noted in response to any of the priming stimuli alone, as measured by the reduction of ferricytochrome c (data not shown), but there was enhanced primed extracellular superoxide production in response to Pam3CSK4 by PMN from TLR2/1 high primers compared to low primers (Figure 2D). Considered in combination, these assays demonstrate that FSL-1 and TNF-α prime intracellular and extracellular ROS generation in PMN from all donors, whereas Pam3CSK4 differentially primes ROS generation in PMN from discrete donor subsets. We postulate that these intracellular endosomal ROS serve a primary role to initiate pro-inflammatory signaling cascades, including activation of MAPK pathways.

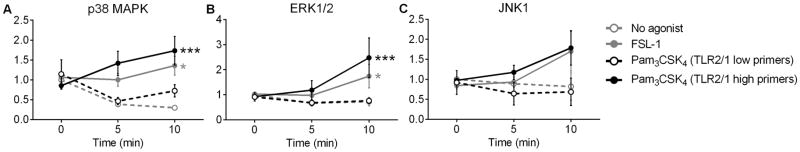

TLR2/1 high primers activate MAPK signaling

We have previously demonstrated that MAPK signaling cascades are activated in PMN primed with endotoxin or TNF-α (1, 4, 24). To quantify MAPK activation downstream of TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 ligation, we treated PMN with FSL-1 or Pam3CSK4 and blotted for phosphorylated p38 MAPK, ERK1/2, and JNK1 from the PMN lysate. FSL-1 elicited significant p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in PMN from all donors (Figure 3). In contrast, Pam3CSK4 treatment induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 in TLR2/1 high primers but no enhancement of phosphorylation in TLR2/1 low primers, indicating concordance between activation of NADPH oxidase activity and MAPK activation. Similar trends were seen with JNK1 phosphorylation (Figure 3C) although not significant. Results were unchanged when total levels of p38, ERK1/2, or JNK1, respectively, were used for normalization (data not shown).

Figure 3. Pam3CSK4 initiates MAPK signaling in PMN from TLR2/1 high primers but not in TLR2/1 low primers.

(A) p38 MAPK, (B) ERK1/2, and (C) JNK1 phosphorylation was quantified by immunoblotting and normalized to β-actin. Mean ± SEM, n ≥ 16 per group. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. P values were calculated by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test to compare between no agonist, 100 ng/ml FSL-1, and 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 at each time point. Asterisks indicate significance compared to no agonist.

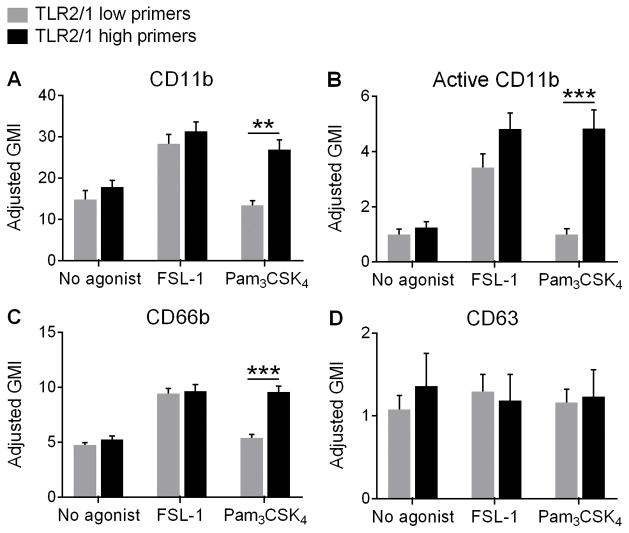

Integrin activation and partial granule mobilization occurs only in primers in response to Pam3CSK4

MAPK activation has been linked to mobilization of intracellular stores of proteins to the cell surface; thus, surface upregulation of these proteins serves as another functional phenotype of neutrophil priming. To analyze this phenotype we studied cell surface expression of critical proteins involved in the neutrophil inflammatory response and in neutrophil activation. FSL-1 elicited upregulation of CD11b, a β2-integrin, on the surface of PMN from all donors. In contrast, Pam3CSK4 only upregulated CD11b expression on PMN from TLR2/1 high primers with no change in CD11b density seen in TLR2/1 low primers as compared to unstimulated cells (Figure 4A). This pattern was also observed when quantitating surface density for the active conformation of CD11b, which promotes PMN adhesion to the endothelium and subsequent cell extravasation (Figure 4B). Secondary, or specific, granules may be partially mobilized as a component of priming to aid PMN movement from the vascular space to sites of infection. We found upregulation of CD66b on the cell surface (a marker of secondary granules) in all donors upon stimulation with FSL-1, but only PMN from TLR2/1 high primers treated with Pam3CSK4 (Figure 4C). No changes in the expression of CD63, an azurophilic granule marker, were seen in any groups or treatments (Figure 4D). This served as our negative control as we would not expect azurophilic granules to be mobilized in response to a priming stimulus alone. Considered in combination, these data suggest that mobilization of intracellular stores of proteins to the cell surface as a component of neutrophil priming is likely connected to ROS generation and MAPK activation, and does not occur in TLR2/1 low primers in response to Pam3CSK4.

Figure 4. Pam3CSK4 induces integrin activation and secondary granule exocytosis in TLR2/1 high primers but not TLR2/1 low primers.

PMN surface expression of (A) CD11b, (B) the active conformation of CD11b, (C) CD66b (a secondary granule marker), and (D) CD63 (a primary granule marker) determined by flow cytometry of PMN from TLR2/1 low primers and TLR2/1 high primers treated with no agonist, 100 ng/ml FSL-1, or 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4. There were no changes from baseline expression levels of CD11b or CD66b in TLR2/1 low primers stimulated with Pam3CSK4. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 5 per group. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student’s t tests.

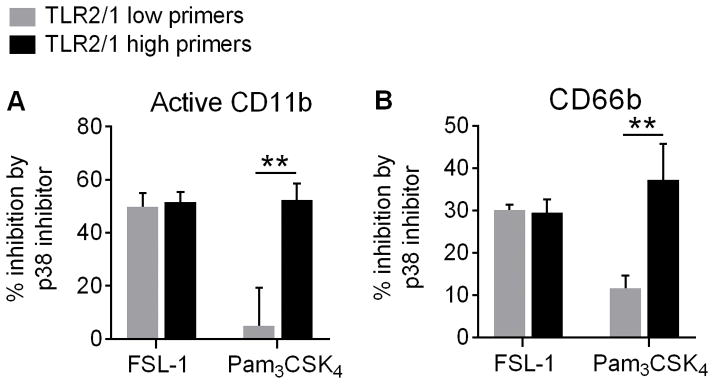

Integrin activation and granule exocytosis are downstream of p38 signaling

To determine whether integrin activation and secondary granule exocytosis occur downstream of p38 MAPK signaling, we pre-treated PMN with a rapidly diffusing p38 inhibitor or an inactive analog control prior to exposing them to a TLR2 agonist. Following treatment with the p38 inhibitor, we observed a significant decrease in both integrin activation (Figure 5A) and secondary granule exocytosis (Figure 5B) in all PMN treated with FSL-1 and in PMN from TLR2/1 high primers treated with Pam3CSK4. As expected, the p38 inhibitor had no effect on TLR2/1 low primers stimulated with Pam3CSK4 as there is no activation of p38 in this population (Figure 5). These results indicate that integrin activation and secondary granule exocytosis following TLR2 stimulation occur downstream of p38 MAPK signaling.

Figure 5. Upregulation of active CD11b and CD66b is downstream of p38 MAPK signaling.

PMN were pretreated with a p38 MAPK inhibitor or inactive analog control prior to exposure to a TLR2 agonist as indicated previously. Surface (A) active CD11b and (B) CD66b expression were then quantified by flow cytometry in TLR2/1 low primers and TLR2/1 high primers. Data are shown as a percentage of surface upregulation inhibited by the p38 MAPK inhibitor. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 5 per group. **p < 0.01, Student’s t tests.

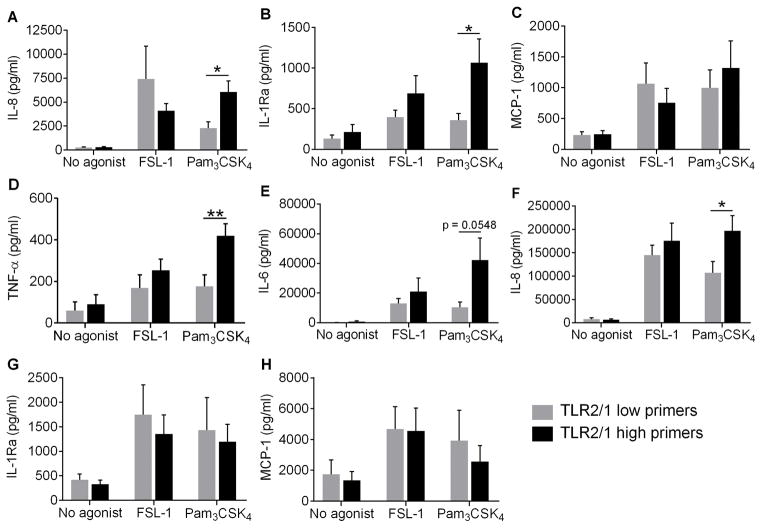

PMN and monocytes from TLR2/1 high primers have enhanced cytokine secretion following Pam3CSK4 stimulation

One mechanism by which innate immune cells orchestrate the inflammatory response is through the production and release of cytokines. We measured cytokine secretion by PMN stimulated with FSL-1 or Pam3CSK4 for 24 h. PMN have been shown to secrete biologically significant levels of proinflammatory IL-8 and MCP-1 and anti-inflammatory IL-1Ra (25). In response to stimulation with Pam3CSK4, PMN from TLR2/1 high primers generated significantly greater amounts of IL-8 and IL-1Ra, but not MCP-1, than PMN from TLR2/1 low primers (Figure 6), whereas PMN from all donors displayed similar levels of cytokine production in response to stimulation with FSL-1. As monocyte cytokine production is often an order of magnitude greater than production generated by PMN, we also investigated monocyte secretion of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, the pattern of cytokine production by monocytes was similar to the PMN responses to Pam3CSK4. Monocytes from donors that had high PMN priming responses secreted more IL-8, IL-6 and, TNF-α, but not IL-1Ra or MCP-1, than monocytes from TLR2/1 low primers (Figure 6). No differences in cytokine production were observed between monocytes from these donors following FSL-1 treatment. These results suggest that TLR2/1 stimuli induce greater cytokine generation in phagocytes from TLR2/1 high primers than low primers, and thus, TLR2/1 high primers may generate an overall greater inflammatory response.

Figure 6. Select cytokines are upregulated in PMN and monocytes from TLR2/1 high primers only following Pam3CSK4 treatment.

PMN secretion of (A) IL-8, (B) IL-1Ra, and (C) MCP-1 and monocyte secretion of (D) TNF-α, (E) IL-6, (F) IL-8, (G) IL-1Ra, and (H) MCP-1 following 24 h treatment with no agonist, 100 ng/ml FSL-1, or 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 was quantified by ELISA in TLR2/1 low primers and TLR2/1 high primers. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 9 per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, Student’s t tests.

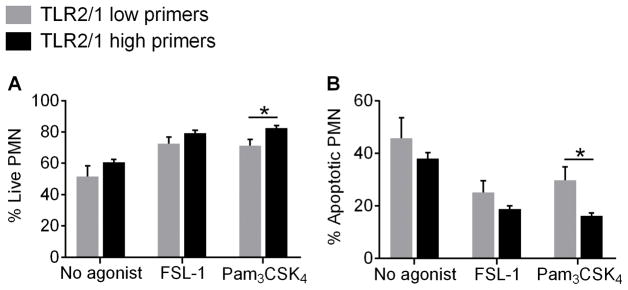

Pam3CSK4 prolongs the lifespan of PMN from TLR2/1 high primers

Based on our cytokine data following extended stimulation with TLR2 ligands and published literature demontrating prolonged PMN lifespan during inflammation in vivo and in vitro (13, 26–28), we investigated whether FSL-1 and Pam3CSK4 delay PMN apoptosis. Minimal numbers of apoptotic PMN were observed at 6 h post-stimulation (data not shown), but about 50% of control (non-stimulated) cells were apoptotic at 24 h post-isolation (Figure 7). FSL-1 treatment significantly prolonged the lifespan of PMN from all donors. However, Pam3CSK4 extended the lifespan of PMN from TLR2/1 high primers to a greater extent than PMN from TLR2/1 low primers as evidenced by fewer apoptotic cells at 24 h post-stimulation. Thus, the increase in cytokine generation by TLR2/1 high primer PMN in response to Pam3CSK4 could be due in part to prolonged PMN lifespan.

Figure 7. Pam3CSK4 delays apoptosis in PMN from TLR2/1 high primers.

Following 24 h treatment with no agonist, 100 ng/ml FSL-1, or 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4, the percentages of (A) live and (B) apoptotic PMN were determined by Annexin V staining in TLR2/1 low primers and TLR2/1 high primers. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 4 per group. *p < 0.05, Student’s t tests.

TLR2/1 high primers have a common TLR1 SNP (rs5743618) that is absent in TLR2/1 low primers

We predicted that the intrinsic difference in PMN TLR2/1 priming phenotypes, and PMN and monocyte cytokine production could be due to a polymorphism in TLR1. Using the Exome Variant Server (University of Washington), we identified two high-frequency nonsynonymous SNPs, rs5743618 (1805G/T) and rs4833095 (743A/G), in the exonic regions of TLR1. These SNPs cause amino acid changes S602I and N248S, respectively. We sequenced these sites in 43 healthy adult donors after determining the priming phenotype of the donors by LUC-CL. All donors that were classified as TLR2/1 low primers were homozygous for the G allele at site 1805G/T, whereas all TLR2/1 high primers were either heterozygous or homozygous for the T allele (Table I). These data strongly indicate that rs5743618 is the causative SNP determining PMN responsiveness to TLR2/1 ligands. For the second SNP sequenced, 743A/G, the G allele was not present in TLR2/1 low primers, but was present in only 77% of the high primers. These data suggest that rs4833095 is not the causative SNP, but rather, is in strong linkage disequilibrium with the causative SNP.

Table I.

All TLR2/1 high primers have a SNP in TLR1 (rs5743618) which is absent in all TLR2/1 low primers.

| 1804G/T (rs5743618)

|

742A/G (rs4833095)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | GT | TT | AA | AG | GG | |

| TLR2/1 low primers (n=21) Count (%) |

21 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TLR2/1 high primers (n=22) Count (%) |

0 (0) | 21 (95.4) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (22.7) | 16 (72.7) | 1 (4.5) |

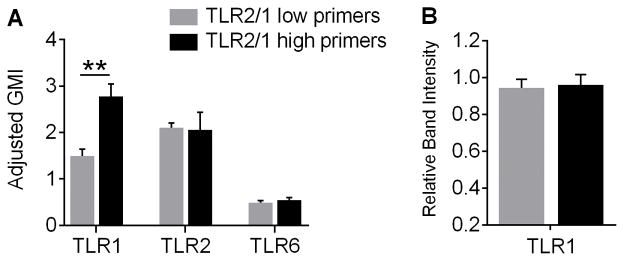

TLR1 surface expression is increased on PMN from TLR2/1 high primers

TLR1_1805G/T is located at the cytoplasmic side of the transmembrane region of TLR1 and cell surface trafficking has recently been demonstrated to be altered by this SNP in several cell types (29). Thus, we predicted that TLR1 trafficking to or from the plasma membrane may be affected in neutrophils. Using flow cytometry, we observed that TLR1, but not TLR2 or TLR6, expression was significantly higher on the surface of PMN from TLR2/1 high primers than low primers (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. TLR1 expression is significantly increased on the surface of PMN from TLR2/1 high primers compared to TLR2/1 low primers, although total cellular proteins levels are similar.

(A) PMN surface expression of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 were quantified by flow cytometry and adjusted to an IgG control. Mean + SEM, n = 7 per group. **p < 0.01, Student’s t test. (B) Total TLR1 protein in whole PMN lysates was quantified by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting in TLR2/1 low primers and TLR2/1 high primers. Mean + SEM, n ≥ 5 per group.

To establish whether the increased surface expression of TLR1 on PMN from TLR2/1 high primers was due to higher total cellular levels of TLR1 protein, we blotted for TLR1 in PMN lysate from TLR2/1 high and low primers. Notably, total cellular TLR1 protein levels were not different between the groups (Figure 8B). This suggests that altered trafficking of TLR1 to or from the PMN surface, rather than dysregulated synthesis of TLR1, leads to the differential priming phenotypes observed between TLR2/1 high and low primers.

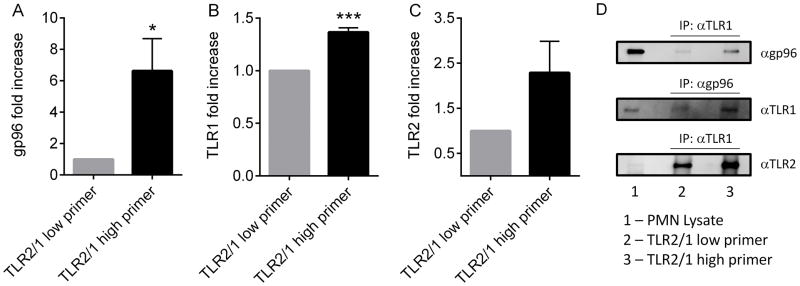

TLR2/1 high primers have enhanced association of TLR1 with the ER chaperone protein gp96

In view of our data suggesting impaired trafficking as a potential mechanism, and the existing literature identifying gp96 as a critical ER chaperone for several TLR family members in other innate immune cell types (18, 30), we investigated the association between this chaperone and TLR1 in our two donor populations. By immunoprecipitation, we observed a significantly increased association of gp96 with TLR1 in TLR2/1 high primers as compared to TLR2/1 low primers (Figure 9A–B, D). After immunoprecipitation for TLR1, we found a 6.6-(±2.06) fold increase in the abundance of gp96 by immunoblotting in neutrophils from TLR2/1 high primers as compared to TLR2/1 low primers using paired samples (N=4). In the TLR1 immunoprecipitates that were blotted for TLR2, there was 2.29-fold greater abundance of TLR2 in TLR2/1 high primers. Although this fold increase did not reach statistical significance, all 4 paired samples showed greater TLR1-TLR2 association in the TLR2/1 high primer PMN. Considered in combination, the altered PMN functional responses demonstrated in TLR2/1 low primers appear to result from impaired association with the ER chaperone gp96, leading to diminished cell surface expression.

Figure 9. Increased association between TLR1 and gp96 in TLR2/1 high primers.

(A) Immunoprecipitation of TLR1 followed by immunoblotting for gp96 demonstrates increased association in TLR2/1 high primers, n = 4. *p < 0.05. (B) Immunoprecipitation of gp96 followed by immunoblotting for TLR1 demonstrates increased association in TLR2/1 high primers, n = 3. ***p < 0.0001, t tests. (C) Immunoprecipitation of TLR1 followed by immunoblotting for TLR2 shows a trend towards increased association in the TLR2/1 high primers, n = 4. (D) Representative immunoblots.

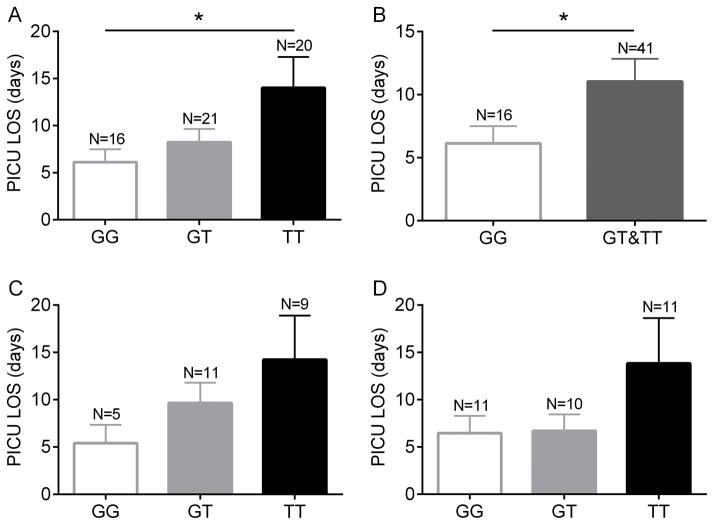

Relationship between TLR1 genotype and outcomes in pediatric sepsis

Based on our data and published literature suggesting that the rs5743618 SNP is linked to outcomes in a number of inflammatory and infectious diseases (5, 7, 8, 19, 31–34), we sequenced samples from a pediatric sepsis database (35). Among 140 children admitted with sepsis or septic shock with positive bacterial cultures from any normally sterile site, 40 patients were homozygous for the G allele at site 1805G/T, 53 patients were heterozygous (G/T), and 47 patients were homozygous for the T allele. These data were analyzed to determine if genotype was related to the clinical outcomes of complicated course (35), maximum organ failure, PICU free days, and PICU length of stay. There was no association between these clinical outcomes and genotype in this cohort (Supplemental Table I). In a subanalysis, we focused exclusively on patients with positive bacterial blood cultures. In this subpopulation, patients who were homozygous for the T allele had significantly increased PICU length of stay, compared to those who were homozygous for the G allele (Figure 10A). Moreover, in separate analyses combining the GT and TT populations (based on our in vitro finding that a single T allele conferred enhanced neutrophil activation), patients with the genotype GG had a significant reduction in PICU length of stay compared to the combined GT and TT group (Figure 10B). There were no statistically significant differences between the genotypes in terms of the outcomes of complicated course or maximum organ failure, although there was a trend towards increased organ failure in the TT genotype (2.25±1.1) in comparison with the GG genotype (1.75 ±1.3). Similarly, the TT patients had a 25% incidence of complicated course vs. a 6.2% incidence in the GG genotype patients. We hypothesized that the impact of this SNP would be most notable in patients with Gram positive bacterial sepsis and thus analyzed Gram positive bacteremia with sepsis and Gram negative separately. Although there were no significant differences between the genotypes due to the low number of patients in each subgroup, the trend towards prolonged PICU LOS in the TT genotype existed for both Gram positive and Gram negative bloodstream infections.

Figure 10. Septic patients homozygous for the 1805T allele with positive blood cultures had significantly longer stays in the PICU.

(A) Correlation between individual genotypes and PICU LOS in patients with positive bacterial blood cultures and sepsis. *p < 0.05 for GG vs. TT paired comparison, p = 0.053 for ANOVA. (B) Comparison between PICU LOS and GG vs. GT + TT combined, *p < 0.05. (C) Comparison between genotypes and PICU LOS in septic patients with Gram positive bacteremia. (D) Comparison between PICU LOS and genotype in septic patients with Gram negative bacteremia.

Neutrophil priming responses in vitro do not differ between GT and TT genotypes

The donor pool utilized for all of our initial in vitro assays of PMN priming had only a single donor homozygous for the T allele. In view of the data obtained from genotyping of the pediatric sepsis database, and a subset of the published literature suggesting that the TT genotype might be phenotypically distinct from the GT genotype (19), we evaluated neutrophil NADPH oxidase priming in a geographically distinct and more racially diverse donor pool. Consistent with data from the initial donor pool, PMN from donors with the GG genotype had minimal/no priming of the respiratory burst after incubation with Pam3CSK4 followed by stimulation with fMLF, as measured by LUC-CL. Notably, PMN from donors that were heterozygous or homozygous for the T allele had nearly identical priming responses (Supplemental Figure 2). PMN from all donors displayed priming in response to stimulation with FSL-1 (data not shown).

Discussion

PMN priming occurs in vitro and in vivo in response to various stimuli. Primed PMN have enhanced responsiveness to secondary stimuli, which may be beneficial or detrimental depending on the context. While primed PMN may eradicate pathogens more efficiently, dysregulated PMN activity or recruitment may lead to excessive oxidant generation and protease release and subsequent host tissue injury in settings such as sepsis (3).

The current study evaluated PMN priming responses to TLR2 agonists and provided evidence of three novel related findings. First, in contrast to previous studies (10, 11, 14) and in contrast to our findings with other TLR ligands (1), we demonstrated that TLR2/1 ligation does not prime PMN from all donors. Fifty percent of donors display direct ROS generation in response to Pam3CSK4 and enhanced responsiveness to subsequent stimulation, whereas the other half have minimal to no priming response. (We referred to these donor subsets as TLR2/1 high primers or TLR2/1 low primers, respectively). In contrast, TLR2/6 ligation by FSL-1 primes PMN from all donors to a similar extent. Second, we showed that TLR2/1 high primers contain at least one copy of a common SNP (rs5743618, 1805G/T) in exon 4 of TLR1 that is not present in TLR2/1 low primers. In a second distinct donor pool, we demonstrated that the presence of a single T allele is sufficient to confer neutrophil priming responses in vitro. And finally, pediatric sepsis and septic shock patients with a positive blood culture and with a copy of the SNP associated with neutrophil priming had prolonged PICU length of stay. Due to its role in modulating PMN and monocyte inflammatory function, we suggest that this SNP may significantly impact, and could possibly predict, patient risk and outcome during severe inflammatory conditions.

TLR1 site 1805G/T has previously been linked to patient risk and outcome in several diseases. The 1805T allele (consistent with our TLR2/1 high primers) has been shown to be protective against pyelonephritis (31), Candidemia (32), tuberculosis (5), and extension of inflammatory bowel disease (33). Conversely, the 1805T allele has been associated with a higher incidence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection (34) and leprosy (7), and increased circulatory dysfunction and mortality in adult sepsis patients (8, 19). Together, these studies provide evidence that the 1805T allele can confer susceptibility to certain diseases and protection against others, giving insight into why both the 1805G and 1805T alleles remain in the human population in high frequency. The high frequency of both alleles is not unexpected as inflammation is evolutionarily necessary and beneficial in certain infectious diseases; however, the extent of inflammation required to restore immunological homeostasis is dependent on the disease context. The major 1805G allele occurs at high frequencies in European, European American, and some Middle Eastern populations while the derived 1805T allele is more frequent in Asian and African populations (7, 36, 37).

The mechanism by which TLR1 site 1805G/T influences innate immune responses has not yet been fully elucidated. Notably, site 1805G/T is located at the cytoplasmic side of the transmembrane domain of TLR1 where it is not likely to affect ligand recognition or binding. In 2007, Johnson et al. reported that monocytes from 1805G homozygous donors lacked TLR1 surface expression by flow cytometry and fluorescent microscopy; however, monocytes from all donors had similar levels of intracellular TLR1 (7). Similarly, a study by Uciechowski et al. revealed that individuals homozygous for 1805G had no surface expression of TLR1 on monocytes, granulocytes, or lymphocytes by flow cytometry (5). In contrast to these studies, we observed detectable TLR1 surface expression on PMN from donors homozygous for the 1805G allele (TLR2/1 low primers), though the levels were significantly below those of PMN from heterozygous donors. This low level surface expression is consistent with our data showing that Pam3CSK4 minimally primes PMN from TLR2/1 low primers in a dose-dependent manner. TLR2/1 and TLR2/6 signaling has previously been shown to be initiated at the plasma membrane in monocytes and to be turned off following receptor/ligand endocytosis (38–40), suggesting that increased or prolonged TLR2/1 surface expression could lead to the phenotype observed in TLR2/1 high primers. Similar to Johnson et al., we observed no difference in intracellular TLR1 levels between donors. More recently, utilizing point mutations in this region of TLR1 in COS7 and HEK 293T cells, it is clear that altered trafficking to the cell surface results from this substitution.

Several endoplasmic reticulum chaperones for TLR proteins have been demonstrated to regulate TLR trafficking (29, 30). A specific role for these ER chaperones in neutrophils had not been previously studied. In the current study, we demonstrate a likely role for the ER chaperone gp96 in TLR1 trafficking in neutrophils. Our data suggest that PMN from donors with the 1805T allele display significantly enhanced association of the gp96 chaperone with TLR1 and significantly greater TLR1-TLR2 association. We are currently seeking to determine if association with this chaperone is required for conformational stability, as has been shown for TLR9 (17). Moreover, the mechanisms regulating heterodimer formation and balance of TLR2/1 vs. TLR2/6 in each cell type are currently unknown, and under investigation in our laboratory.

Previous studies have shown that Pam3CSK4-stimulated monocytes and whole blood from homozygous 1805G donors generate less TNF-α and IL-6, respectively, than monocytes and whole blood samples from donors with at least one copy of 1805T (7, 37). Similarly, HEK 293T cells transfected with the TLR1_1805G allele have significantly less NF-κB activation than cells transfected with TLR1_1805T following exposure to Pam3CSK4 (37). Consistent with previous studies, we observed that monocytes from homozygous 1805G donors secreted less TNF-α, as well as IL-6 and IL-8, than monocytes from heterozygous donors. For the first time, we also showed that PMN from donors homozygous for TLR1_1805G have minimal priming responses to Pam3CSK4 compared to heterozygous donors. This was evidenced by significantly less ROS generation, MAPK signaling, degranulation, and cytokine production. Importantly, PMN play prominent roles in the pathogenesis of several diseases impacted by TLR1_1805G/T, including pyelonephritis (41), candida infections (42), tuberculosis (43), inflammatory bowel disease (44), leprosy (45), and sepsis (46). Thus, we predict that the degree of PMN activation through TLR2/1, as a consequence of TLR1 genotype, significantly affects patient susceptibility and/or outcome for several diseases.

Further evidence for the importance of this SNP in human disease was generated by our analysis of the frequency of each of these genotypes in a pediatric sepsis database. Our finding that patients with one or two copies of this SNP had prolonged stay in a pediatric ICU after sepsis with positive blood culture demonstrates the importance of understanding host genetic susceptibility. In the early years of treating sepsis, the mortality from septicemia was a consequence of the initial “septic shock” phase of disease. As modern intensive care practice has evolved, the early mortality from sepsis has declined, and both morbidity and mortality result from multi-organ system dysfunction that stem from the host inflammatory response to the pathogen (47). Appropriate termination of host inflammation is critical to successful recovery. Our data suggest that under some conditions exuberant neutrophil and monocyte inflammatory activation delays recovery as suggested by longer requirements for ICU admission. Host differences in innate immune responses likely have a major impact on outcomes from sepsis and other systemic inflammatory diseases. Better understanding of these basic immune mechanisms will be required to improve outcomes.

In recent murine studies, Pam3CSK4 was demonstrated to boost immunogenicity to a trivalent influenza vaccine and a Leishmania (TRYP antigen) vaccine (48, 49). This enhanced protection was thought to be due to stimulation of the innate immune system and production of a cytokine mediator that enhances T cell responses. Our research has significant implications for the usefulness of Pam3CSK4 as a potential human vaccine adjuvant. Here we have demonstrated that Pam3CSK4 induces a much stronger innate immune response in human cells with at least one copy of the TLR1_1805T allele compared to those with two copies of the TLR_1805G allele. Thus, the presence or absence of this allele could have a significant impact on the effectiveness of a human vaccine utilizing Pam3CSK4 as an adjuvant due to varied degrees of innate immune stimulation.

In summary, this study defined a novel mechanism of action for TLR1 SNP rs5743618 in modulating PMN priming responses. As the extent of PMN priming can impact the severity and outcome of several global diseases, it is important to understand how this SNP affects PMN activation. Our better understanding of the basic biology of leukocyte responses and the impact of host genetic variability on these responses is required to define the next therapeutic interventions. As we look forward to an era of personalized medicine, we predict that patient genotyping for this SNP could be used to predict patient risk in heterogeneous diseases such as sepsis, and thus, could inform patient treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Flow cytometry data were obtained at the Flow Cytometry Facility, a Carver College of Medicine Core Research Facilities/Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Laboratory at the University of Iowa.

JGM is funded by NIH/NIAID 1R21 AI109127-01, and PJF is funded by NIH/NIAMS 1R01AR059703-01A1.

Abbreviations

- LUC_CL

lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence

- PICU

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- RLU

relative light unit

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Moreland JG, Davis AP, Matsuda JJ, Hook JS, Bailey G, Nauseef WM, Lamb FS. Endotoxin priming of neutrophils requires NADPH oxidase-generated oxidants and is regulated by the anion transporter ClC-3. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:33958–33967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamb FS, Hook JS, Hilkin BM, Huber JN, Volk AP, Moreland JG. Endotoxin priming of neutrophils requires endocytosis and NADPH oxidase-dependent endosomal reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12395–12404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.306530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigand MA, Horner C, Bardenheuer HJ, Bouchon A. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2004;18:455–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volk AP, Barber BM, Goss KL, Ruff JG, Heise CK, Hook JS, Moreland JG. Priming of neutrophils and differentiated PLB-985 cells by pathophysiological concentrations of TNF-alpha is partially oxygen dependent. J Innate Immun. 2011;3:298–314. doi: 10.1159/000321439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uciechowski P, Imhoff H, Lange C, Meyer CG, Browne EN, Kirsten DK, Schroder AK, Schaaf B, Al-Lahham A, Reinert RR, Reiling N, Haase H, Hatzmann A, Fleischer D, Heussen N, Kleines M, Rink L. Susceptibility to tuberculosis is associated with TLR1 polymorphisms resulting in a lack of TLR1 cell surface expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:377–388. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0409233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Marques CS, Brito-de-Souza VN, Guerreiro LT, Martins JH, Amaral EP, Cardoso CC, Dias-Batista IM, Silva WL, Nery JA, Medeiros P, Gigliotti P, Campanelli AP, Virmond M, Sarno EN, Mira MT, Lana FC, Caffarena ER, Pacheco AG, Pereira AC, Moraes MO. Toll-like receptor 1 N248S single-nucleotide polymorphism is associated with leprosy risk and regulates immune activation during mycobacterial infection. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:120–129. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson CM, Lyle EA, Omueti KO, Stepensky VA, Yegin O, Alpsoy E, Hamann L, Schumann RR, Tapping RI. Cutting edge: A common polymorphism impairs cell surface trafficking and functional responses of TLR1 but protects against leprosy. J Immunol. 2007;178:7520–7524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pino-Yanes M, Corrales A, Casula M, Blanco J, Muriel A, Espinosa E, Garcia-Bello M, Torres A, Ferrer M, Zavala E, Villar J, Flores C. Common variants of TLR1 associate with organ dysfunction and sustained pro-inflammatory responses during sepsis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi F, Means TK, Luster AD. Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood. 2003;102:2660–2669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seifert R, Schultz G, Richter-Freund M, Metzger J, Wiesmuller KH, Jung G, Bessler WG, Hauschildt S. Activation of superoxide formation and lysozyme release in human neutrophils by the synthetic lipopeptide Pam3Cys-Ser-(Lys)4. Involvement of guanine-nucleotide-binding proteins and synergism with chemotactic peptides. The Biochemical journal. 1990;267:795–802. doi: 10.1042/bj2670795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabroe I, Prince LR, Jones EC, Horsburgh MJ, Foster SJ, Vogel SN, Dower SK, Whyte MK. Selective roles for Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 in the regulation of neutrophil activation and life span. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:5268–5275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilde I, Lotz S, Engelmann D, Starke A, van Zandbergen G, Solbach W, Laskay T. Direct stimulatory effects of the TLR2/6 ligand bacterial lipopeptide MALP-2 on neutrophil granulocytes. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2007;196:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s00430-006-0027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francois S, El Benna J, Dang PM, Pedruzzi E, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Elbim C. Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by TLR agonists in whole blood: involvement of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and NF-kappaB signaling pathways, leading to increased levels of Mcl-1, A1, and phosphorylated Bad. J Immunol. 2005;174:3633–3642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farhat K, Riekenberg S, Heine H, Debarry J, Lang R, Mages J, Buwitt-Beckmann U, Roschmann K, Jung G, Wiesmuller KH, Ulmer AJ. Heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 expands the ligand spectrum but does not lead to differential signaling. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2008;83:692–701. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitmore LC, Hilkin BM, Goss KL, Wahle EM, Colaizy TT, Boggiatto PM, Varga SM, Miller FJ, Moreland JG. NOX2 protects against prolonged inflammation, lung injury, and mortality following systemic insults. J Innate Immun. 2013;5:565–580. doi: 10.1159/000347212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitmore LC, Goss KL, Newell EA, Hilkin BM, Hook JS, Moreland JG. NOX2 protects against progressive lung injury and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L71–82. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00054.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks JC, Sun W, Chiosis G, Leifer CA. Heat shock protein gp96 regulates Toll-like receptor 9 proteolytic processing and conformational stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421:780–784. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randow F, Seed B. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone gp96 is required for innate immunity but not cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:891–896. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wurfel MM, Gordon AC, Holden TD, Radella F, Strout J, Kajikawa O, Ruzinski JT, Rona G, Black RA, Stratton S, Jarvik GP, Hajjar AM, Nickerson DA, Rieder M, Sevransky J, Maloney JP, Moss M, Martin G, Shanholtz C, Garcia JG, Gao L, Brower R, Barnes KC, Walley KR, Russell JA, Martin TR. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms affect innate immune responses and outcomes in sepsis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:710–720. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-462OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nauseef WM. Isolation of human neutrophils from venous blood. Methods in molecular biology. 2007;412:15–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-467-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis Volk AP, Moreland JG. ROS-containing endosomal compartments: implications for signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2014;535:201–224. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397925-4.00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson PJ, Chen S, Tayeh MK, Ochoa L, Leal SM, Pelet A, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Majeed HA, El-Shanti H. Homozygous mutations in LPIN2 are responsible for the syndrome of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia (Majeed syndrome) Journal of medical genetics. 2005;42:551–557. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Freishtat RJ, Anas N, Meyer K, Checchia PA, Weiss SL, Shanley TP, Bigham MT, Banschbach S, Beckman E, Harmon K, Zimmerman JJ. Corticosteroids are associated with repression of adaptive immunity gene programs in pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:940–946. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0171OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan SR, Al-Hertani W, Byers D, Bortolussi R. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein- and CD14-dependent activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 by lipopolysaccharide in human neutrophils is associated with priming of respiratory burst. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4068–4074. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4068-4074.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaillon S, Galdiero MR, Del Prete D, Cassatella MA, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Neutrophils in innate and adaptive immunity. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:377–394. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon HU. Neutrophil apoptosis pathways and their modifications in inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2003;193:101–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez MF, Watson RW, Parodo J, Evans D, Foster D, Steinberg M, Rotstein OD, Marshall JC. Dysregulated expression of neutrophil apoptosis in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1263–1269. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430360009002. discussion 1269–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ertel W, Keel M, Infanger M, Ungethum U, Steckholzer U, Trentz O. Circulating mediators in serum of injured patients with septic complications inhibit neutrophil apoptosis through up-regulation of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. J Trauma. 1998;44:767–775. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199805000-00005. discussion 775–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart BE, Tapping RI. Cell surface trafficking of TLR1 is differentially regulated by the chaperones PRAT4A and PRAT4B. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:16550–16562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Liu B, Dai J, Srivastava PK, Zammit DJ, Lefrancois L, Li Z. Heat shock protein gp96 is a master chaperone for toll-like receptors and is important in the innate function of macrophages. Immunity. 2007;26:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawn TR, Scholes D, Li SS, Wang H, Yang Y, Roberts PL, Stapleton AE, Janer M, Aderem A, Stamm WE, Zhao LP, Hooton TM. Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to urinary tract infections in adult women. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plantinga TS, Johnson MD, Scott WK, van de Vosse E, Velez Edwards DR, Smith PB, Alexander BD, Yang JC, Kremer D, Laird GM, Oosting M, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, van Dissel JT, Walsh TJ, Perfect JR, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG. Toll-like receptor 1 polymorphisms increase susceptibility to candidemia. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:934–943. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierik M, Joossens S, Van Steen K, Van Schuerbeek N, Vlietinck R, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Toll-like receptor-1, -2, and -6 polymorphisms influence disease extension in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195389.11645.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor BD, Darville T, Ferrell RE, Kammerer CM, Ness RB, Haggerty CL. Variants in toll-like receptor 1 and 4 genes are associated with Chlamydia trachomatis among women with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:603–609. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Anas N, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Bigham MT, Weiss SL, Fitzgerald J, Checchia PA, Meyer K, Shanley TP, Quasney M, Hall M, Gedeit R, Freishtat RJ, Nowak J, Shekhar RS, Gertz S, Dawson E, Howard K, Harmon K, Beckman E, Frank E, Lindsell CJ. Developing a clinically feasible personalized medicine approach to pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:309–315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1864OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heffelfinger C, Pakstis AJ, Speed WC, Clark AP, Haigh E, Fang R, Furtado MR, Kidd KK, Snyder MP. Haplotype structure and positive selection at TLR1. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawn TR, Misch EA, Dunstan SJ, Thwaites GE, Lan NT, Quy HT, Chau TT, Rodrigues S, Nachman A, Janer M, Hien TT, Farrar JJ, Aderem A. A common human TLR1 polymorphism regulates the innate immune response to lipopeptides. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2280–2289. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsen NJ, Deininger S, Nonstad U, Skjeldal F, Husebye H, Rodionov D, von Aulock S, Hartung T, Lien E, Bakke O, Espevik T. Cellular trafficking of lipoteichoic acid and Toll-like receptor 2 in relation to signaling: role of CD14 and CD36. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:280–291. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triantafilou M, Gamper FG, Haston RM, Mouratis MA, Morath S, Hartung T, Triantafilou K. Membrane sorting of toll-like receptor (TLR)-2/6 and TLR2/1 heterodimers at the cell surface determines heterotypic associations with CD36 and intracellular targeting. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31002–31011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakao Y, Funami K, Kikkawa S, Taniguchi M, Nishiguchi M, Fukumori Y, Seya T, Matsumoto M. Surface-expressed TLR6 participates in the recognition of diacylated lipopeptide and peptidoglycan in human cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1566–1573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meylan PR, Markert M, Bille J, Glauser MP. Relationship between neutrophil-mediated oxidative injury during acute experimental pyelonephritis and chronic renal scarring. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2196–2202. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2196-2202.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fradin C, De Groot P, MacCallum D, Schaller M, Klis F, Odds FC, Hube B. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:397–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowe DM, Redford PS, Wilkinson RJ, O’Garra A, Martineau AR. Neutrophils in tuberculosis: friend or foe? Trends Immunol. 2012;33:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fournier BM, Parkos CA. The role of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:354–366. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliveira RB, Moraes MO, Oliveira EB, Sarno EN, Nery JA, Sampaio EP. Neutrophils isolated from leprosy patients release TNF-alpha and exhibit accelerated apoptosis in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:364–371. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kovach MA, Standiford TJ. The function of neutrophils in sepsis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25:321–327. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283528c9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hotchkiss RS, Coopersmith CM, McDunn JE, Ferguson TA. The sepsis seesaw: tilting toward immunosuppression. Nature medicine. 2009;15:496–497. doi: 10.1038/nm0509-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caproni E, Tritto E, Cortese M, Muzzi A, Mosca F, Monaci E, Baudner B, Seubert A, De Gregorio E. MF59 and Pam3CSK4 boost adaptive responses to influenza subunit vaccine through an IFN type I-independent mechanism of action. J Immunol. 2012;188:3088–3098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jayakumar A, Castilho TM, Park E, Goldsmith-Pestana K, Blackwell JM, McMahon-Pratt D. TLR1/2 activation during heterologous prime-boost vaccination (DNA-MVA) enhances CD8+ T Cell responses providing protection against Leishmania (Viannia) PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.