Abstract

Because sites of seizure origin may be unknown or multifocal, identifying targets from which activation can suppress seizures originating in diverse networks is essential. We evaluated the ability of optogenetic activation of the deep/intermediate layers of the superior colliculus (DLSC) to fill this role. Optogenetic activation of DLSC suppressed behavioral and electrographic seizures in the pentylenetetrazole (forebrain+brainstem seizures) and Area Tempestas (forebrain/complex partial seizures) models; this effect was specific to activation of DLSC, and not neighboring structures. DLSC activation likewise attenuated seizures evoked by gamma butyrolactone (thalamocortical/absence seizures), or acoustic stimulation of genetically epilepsy prone rates (brainstem seizures). Anticonvulsant effects were seen with stimulation frequencies as low as 5 Hz. Unlike previous applications of optogenetics for the control of seizures, activation of DLSC exerted broad-spectrum anticonvulsant actions, attenuating seizures originating in diverse and distal brain networks. These data indicate that DLSC is a promising target for optogenetic control of epilepsy.

Keywords: absence epilepsy, temporal lobe epilepsy, generalized epilepsy, rat, channelrhodopsin-2, partial seizure, deep brain stimulation

Introduction

Epilepsy affects an estimated 50 million people world-wide (Ngugi et al., 2010). Unfortunately, up to a third of patients do not achieve seizure control with currently available pharmacotherapy (Kwan and Brodie, 2000). Deep brain stimulation (DBS) may be beneficial in patients for whom no other therapeutic option exists, and moreover, may represent an alternative to removal of brain tissue. Current DBS targets in epilepsy (e.g., the anterior nucleus of the thalamus) show partial efficacy, but are also associated with cognitive side effects (Hartikainen et al., 2014). Thus, identification of new targets and approaches for brain stimulation in epilepsy is particularly compelling.

One approach of interest is optogenetics; this method allows for high spatiotemporal, cell-type, and pathway specific targeting of neuronal stimulation (Boyden et al., 2005; Gradinaru et al., 2010). Optogenetics may offer significant advantages over electrical DBS methods by minimizing issues associated with activation of fibers of passage, current spread, and cell targeting. Moreover, high-fidelity temporal control over neural firing may allow for finer tuning of patterns of activation. To date, most efforts employing optogenetics for seizure control have been primarily focused on circuitry within which the seizures are generated (Krook-Magnuson et al., 2013), but see: (Krook-Magnuson et al., 2014). While these studies demonstrate that optogenetics can be employed to control focal seizures, clinically, the site of seizure initiation is often unknown or multifocal, as seizures may arise from interconnected but discrete brain networks (Forcelli and Gale, 2014). Thus, evaluating endogenous circuits that can impede pathological network synchronization and exert a broad-spectrum effect is vital.

One region that has received particular attention for broad-spectrum anticonvulsant effects is the deep/intermediate layers of the superior colliculus (DLSC). Pharmacological activation of DLSC neurons or pharmacological silencing activity of the substantia nigra pars reticulata, the major inhibitory input to the DLSC, is potently anticonvulsant (Dean and Gale, 1989; Depaulis et al., 1994; Gale et al., 1993; Iadarola and Gale, 1982). It has also been suggested that the DLSC is the critical mediator of nigral seizure control (Garant and Gale, 1987). While the effect of DLSC activation has been well studied in seizure control using focal microinjections, this is not a translational approach. Several major drawbacks to this approach that are avoided by optogenetics are the need for chronic intracerebral drug delivery, issues associated with drug spread, and the lack of temporal control of activity. Because optogenetics allows for high-fidelity control of the timing and frequency of stimulation, this method enables examination of different stimulation paradigms, as well as stimulation both prior to and after the onset of seizure activity.

Here, we employed an optogenetic approach to probe the anticonvulsant effect of DLSC activation in four seizure models: i) seizures evoked by systemic pentylenetetrazole (PTZ), which activates thalamocortical, forebrain, and hindbrain seizure networks; ii) limbic motor seizures evoked focally from piriform cortex, which exclusively activates forebrain seizure networks; iii) spike-wave seizures evoked by gamma butyrolactone, which activates a thalamocortical seizure network; and iv) audiogenic seizures (AGS) in genetically epilepsy prone rats (GEPRs), which activates a brainstem seizure network. While several of these models have been examined using other methods of SC stimulation, there have been no studies that directly compare the efficacy of DLSC activation across models using the same experimental procedures.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult, male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (280–300 g at the start of the study) were purchased from Harlan (Frederick, MD) and adult female GEPR-3s (~6 weeks of age at the time of surgery) were obtained from our colony that is maintained at Georgetown University Medical Center. Animals were housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room in the Division of Comparative Medicine at Georgetown University with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures were performed during the light phase of the light-dark cycle (0600-1800, lights on). This study was approved by the Georgetown University Animal Care and Use Committee, and conducted in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council (U.S.) et al., 2011).

Surgery

Animals were anesthetized with 3 ml/kg equithesin (a combination of sodium pentobarbital, chloral hydrate, ethanol, and magnesium sulfate, all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and placed into a Kopf stereotaxic frame (Tujunga, CA). For all experimental groups, rAAV5-hSyn-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry (UNC Vector Core) was microinjected into the DLSC bilaterally through a 30-gauge dental needle. This vector allows for neuron-specific targeting of opsin expression (Kügler et al., 2003). The injection coordinates for the DLSC were: 5.0 mm posterior to bregma, 2.5 mm lateral to midline, and 4.5 mm ventral to the dura, with the incisor bar 5.0 mm above the interaural line (Pellegrino and Cushman, 1967). Microinjections consisted of 1.5–2μl of virus that was injected sequentially in each DLSC at a rate of 0.2 μl/min; the injection needle was left in place for at least 5 min to allow virus diffusion before retraction. Following the microinjections, an optical fiber (200 μm core, 0.22NA, Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) was implanted 0.2 mm dorsal to each injection site. Optical fibers were made according to a previously described protocol (Sparta et al., 2012) and held in place with jeweler’s screws and dental acrylic.

Electroencephalography

EEG screw electrodes were implanted through holes in the skull such that the bottom of each screw was in contact with the dura. Each animal was implanted with 6 screw electrodes: bilaterally over the parietal lobe, bilaterally over the frontal lobe, and two over the cerebellum (ground and reference). All animals implanted with EEG electrodes also received bilateral DLSC injections of optogenetic virus and optical fiber implants as described above. EEG wires were routed into a plastic pedestal (PlasticsOne, Roanoke, VA) and held in place with dental acrylic. EEG recordings were performed in awake, unrestrained animals by coupling the pedestal to a rat EEG preamplifier and amplifier (Pinnacle Technologies, Lawrence, KS). Data were recorded using LabChart 7 and 8 (AD instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) with a 60 Hz low pass filter. Electrographic traces are derived from frontal leads referenced to the cerebellum. As described below EEGs were performed for the pentylenetetrazole, Area Tempestas, and gamma butyrolactone models. Cortical electrographic activity is clearly apparent in each of these models without the need for depth recordings.

Optogenetic stimulation

Behavioral testing commenced 3 weeks post-surgery to allow for transgene expression and normalization of seizure threshold (Forcelli et al., 2013). The implanted optical fibers were connected to fiber-coupled diode pumped solid state lasers (OEM Laser Systems, Midvale, UT) with a wavelength of 473 nm.

In order to ensure consistent light delivery across subjects, we measured the power loss for each fiber prior to implantation and calibrated input as needed at the time of testing to deliver 10–12 mW out the tip of the implanted fiber. Unmodulated light delivery was continuous, whereas 5 Hz and 100 Hz delivery were pulsed with a 50% duty cycle using a BK Precision pulse generator (Yorba Linda, CA). 100 Hz light delivery was selected based on the report of Sahibzada and colleagues (Sahibzada et al., 1986), which demonstrated behavioral responses to SC activation with this stimulation frequency. 5 Hz was selected as it is the low end of the range of the frequency of oscillations reported in the SC (Brecht et al., 1999). Animals were connected to fiber optics prior to seizure induction, and stimulation was initiated immediately following or concurrent with chemoconvulsant administration or acoustic stimulation. Optogenetic stimulation lasted the entire observation period. The experiments in this report were performed using a repeated measures design, with each animal serving as its own control (i.e., each rat was tested with and without optogenetic stimulation). To ensure there was an seizure response to attenuate, all animals had a baseline test session prior to initiating optogenetic stimulation. To minimize order effects, some animals were tested with optogenetic stimulation as the first data point analyzed, and others with baseline as the first point, i.e., the second “baseline” (occurring after the optogenetic manipulation) was analyzed. A minimum of ~20% of animals in each experimental group were tested in this manner.

Pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) seizures

Twenty-five SD rats were used for these experiments, of which 4 animals had virus/fiber optic placement within the inferior colliculus/intracollicular nucleus and are thus presented separately as site-specificity controls in Fig 2G. 19 SD rats received baseline seizure testing as well as at least one experimental test session with 100 Hz stimulation. 6 SD rats received baseline seizure testing as well as at least one session with 5 Hz stimulation.

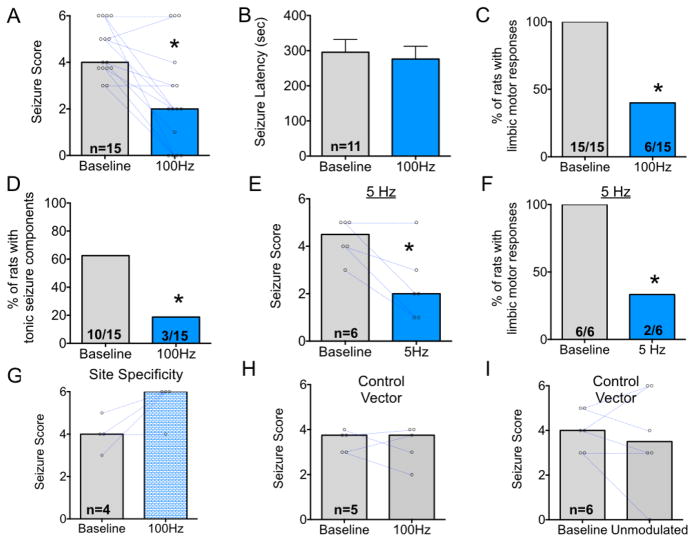

Figure 2. Optogenetic activation of DLSC attenuates forebrain and hindbrain seizure manifestations in response to pentylenetetrazole.

A. Bars indicate median seizure score; points show values for individual subjects and are connected by blue lines to indicate pre-to-post test changes in seizure score. B. Mean (+SEM) latency to first seizure manifestation (typically a myoclonic jerk). Only animals that displayed seizure responses are presented in this graph. C. Proportion of animals with limbic motor seizure responses (i.e., a score of 3 or greater) D. Proportion of animals displaying a tonic response (i.e., roll/twist, or tonic forelimb extension). E. Bars show median seizure score using the conventions in (A), under baseline and 5 Hz stimulation conditions. F. Proportion of animals with limbic motor seizure responses under baseline and 5 Hz stimulation conditions. G. Median seizure severity in the four animals with fibers and/or virus misplaced outside of SC. H. Median seizure severity in 5 animals injected with a control vector (lacking ChR2) under baseline and 100 Hz stimulation conditions. I. Median seizure severity in 6 animals injected with a control vector (lacking ChR2) under baseline and unmodulated stimulation conditions. * = P<0.05.

PTZ (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.9% saline at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and administered via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at an initial dose of 25 mg/kg. To maximize the utility of each animal, this dose was adjusted based on individual variations in response to PTZ. Baseline doses were calibrated such that each animal displayed a baseline Racine score between 3 and 5. For example, if an animal failed to display behavioral seizure response to 25 mg/kg dose, the dose was elevated by 10%. Once a dose was established for an individual rat, the same dose was used both for optogenetic testing and for baseline testing sessions. The final PTZ doses ranged from 22.5 mg/kg to 35 mg/kg, with a median dose of 26 mg/kg.

PTZ seizures were scored using a modified Racine’s scale as we have previously described (Forcelli et al., 2012a, 2011): 1 = single myoclonic jerk; 2 = multiple myoclonic jerks, unilateral forelimb clonus; 3 = bilateral facial and forelimb clonus (FFC); 3.5 = FFC with a body twist; 3.75 = FFC with a full body roll; 4 = FFC with rearing; 4.5 = FFC with rearing and a body twist; 5 = FFC with rearing and loss of balance; and 6 = running bouncing seizure +/− tonic forelimb extension.

Tests with PTZ were separated by at least 48 hours and the order of testing (i.e., with and without stimulation) was balanced to avoid potential confounds associated with repeated dosing with PTZ. Due to the nature of the stimulation (i.e., flashing light) it was impossible to blind the observes to the nature of the experimental session. Detailed behavioral observations were made in real-time by trained observers and scores were assigned after data collection based on the observation notes by a blinded observer.

Behavioral seizure monitoring was selected as the primary endpoint for this experiment because it offers greater sensitivity to changes in seizure activity as compared to sparse sampling cortical EEG. While electrographic monitoring can detect sub-clinical seizures (i.e., those without behavioral manifestations), it does not predict or distinguish between behavioral seizure stages. Some (Bergstrom et al., 2013) have interpreted this to mean that behavioral seizure scores are arbitrary. We, by contrast, take this to indicate that standard rodent EEG does not provide sufficient information to distinguish between fundamentally different behavioral seizure patterns. Based on the differences in motor output, these seizures must by definition engage divergent brain circuits.

Nevertheless, in a subset of animals, EEGs were recorded to confirm behavioral seizure scoring. For EEG assessment of convulsive seizure activity after PTZ, animals were monitored for 30 min; EEGs were analyzed offline by a treatment blind observer. Moreover, as described in the results, we also performed additional analysis to overcome the limitation of behavioral seizure scoring (i.e., electroclinical uncoupling).

For optogenetic testing, the light source was activated immediately after administration of PTZ and animals were observed for 30 minutes after the time of injection to monitor seizure activity. Seizures in this model typically occur within the first 5 minutes following drug administration, and with the doses we used, typically self-terminate within 5–10 minutes of onset.

Piriform cortex (Area Tempestas) seizures

Twenty-one SD rats were used for these experiments. A stainless steel guide cannula was stereotaxically implanted above the left AT (4.0 mm anterior to bregma, 3.5 mm lateral to midline, 5.5 mm ventral to the dura). At the time of drug infusion an internal cannula was placed to extend an additional 2 mm to reach the target site. Coordinates are derived from the atlas of Pelligrino and Cushman (Pellegrino and Cushman, 1967), with the incisor bar placed 5mm above the interaural line (Dybdal and Gale, 2000; Piredda and Gale, 1985).

Bicuculline methiodide (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.9% saline at a concentration of 1 mM. Initially, 100 pmol of bicuculline was microinjected into the AT at a rate of 0.2 μl/min (Piredda and Gale, 1985); microinjection procedures follow those we have previously described (Forcelli et al., 2012c; West et al., 2012). The dose was subsequently increased as necessary (final range 100–280 pmol) to elicit a seizure scoring between 3–5, using a modified Racine scale, as previously described: (Cassidy and Gale, 1998; Dybdal and Gale, 2000) 0.5 = jaw clonus; 1 = myoclonic jerks of the contralateral forelimb; 2 = forelimb clonus (with or without facial clonus); 3 = bilateral facial and forelimb clonus; 4 = rearing plus bilateral facial and forelimb clonus; 5 = loss of balance in addition to rearing and bilateral facial and forelimb clonus. For optogenetic testing, the light source was turned on when the injection was completed and animals were subsequently observed for 60 minutes. Detailed behavioral observations were made in real-time by trained observers and scores were assigned after data collection based on the observation notes by a blinded observer.

15 SD rats were tested on at least one baseline (no stimulation) session and at least one session with 100 Hz stimulation. In a subset of these animals (n=7), stimulation was initiated after the first behavioral seizure manifestation in order to see if seizures could be halted after they had already begun.

6 SD rats were used for 5 Hz stimulation experiments; these animals were also used for EEG confirmation of seizure activity. As in the other experiments, we employed cortical EEG electrodes, which are sufficient to capture complex partial seizure manifestations evoked from Area Tempestas (Piredda and Gale, 1985).

Audiogenic seizure (AGS) testing

Ten GEPR-3s that exhibited AGS susceptibility were used for these experiments, one of which displayed overt running responses to optical stimulation. Four weeks after surgery, GEPR-3s were tested for AGS responses. The acoustic stimulation consisted of 105–110 dB pure tones (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) or 110 dB mixed sounds (delivered via an electrical bell). Acoustic stimulation presented until a seizure was elicited, or for 60 sec if no seizure activity was observed. Sixty min after baseline AGS responses, GEPR-3s were bilaterally stimulated at 5 Hz starting ~30 s prior to presentation of AGS-inducing stimuli.

Convulsive behavior was classified into four stages: 0 = no seizure response to acoustic stimulus, 1 = one episode of wild running seizures (WRS), 2 = two or more WRS episodes of WRS, 3 = one WRS episode followed by tonic-clonic seizures characterized by bouncing clonus, and tonic dorsiflexion of the neck and shoulder. AGS severity, latency to seizure onset and seizure duration were scored in real-time by two simultaneous observers and recorded using a video monitoring system (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT).

Given that no epileptiform activity is seen in the cortex of GEPR-3s following a single AGS (Naritoku et al., 1992) and due to the limited availability of GEPR-3 rats, we only examined behavioral seizures in this subgroup. The GEPR-3 experiments were conducted after the other experiments reported in this paper, and again, due to small colony size, animals were only tested with 5 Hz stimulation, which had previously found to be effective in the other models.

Gamma butyrolactone (GBL) seizures

Nine SD rats were used for these experiments, of which 5 were tested with both unmodulated and frequency modulated stimulation.

GBL (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.9% saline at a concentration of 100 mg/ml and administered via i.p. injection (70 mg/kg). Animals were monitored for the occurrence of spike-and-wave discharge (SWDs) activity for 20 min after the time of injection. Electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring was selected as the dependent measure for these experiments, as behavioral signs of absence-like seizures are subtle and unreliable as compared to EEG measurements. Thalamocortical (absence) seizures are readily detectable as generalized spike-and-wave discharges on the cortical EEG.

EEG activity was monitored for 20 minutes after GBL injection for each of four session types: GBL alone, GBL in combination with 100 Hz optogenetic stimulation, GBL in combination with 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation, and GBL in combination with unmodulated stimulation. Unmodulated stimulation was used to determine if patterned stimulation was required for anticonvulsant activity. To avoid prolonged light delivery (and minimize the risk of tissue damage), we examined unmodulated stimulation only in this, and not the other models. Thus, the unmodulated data, while not comparable to the other models tested, are presented as additional information.

SWDs were assessed offline using LabChart 8 by a treatment-blind observer. Signal was filtered (band pass 2–50 Hz) and SWDs were differentiated from normal runs of alpha rhythm based on amplitude, as SWDs showed peak-to-peak amplitude that was >2x the background activity. A subset of 15-min EEG recordings (n=20) was analyzed in two separate sessions to provide a measure of intra-rater reliability. There was a high degree of reliability across observations (Pearson’s R=0.93) with no statistical difference between the mean cumulative time exhibiting SWDs (observation 1 = 119 sec, observation 2 = 120 sec, t=0.15, df=19, P=0.9).

Histology

Following testing, animals were deeply anesthetized with equithesin and perfused with 10 mM phosphate buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Implants were carefully retracted from the brain after perfusion. Brains were removed and cryoprotected in sucrose (30% w/v) until cryosectioning. Coronal sections (40 μm) were slide-mounted and stored at −80°C until histochemical processing. Slides were blocked (3.75% normal goat serum, 2% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% Triton X-100 in TBS). Slides were incubated for up to 24 hours with primary antibody (1:2000, rabbit anti-dsRED, ClonTech, Mountain View, CA) at 4°C and then incubated for 90 min with secondary antibody (1:1000, goat anti-rabbit, AF594, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at room temperature. Slides were washed and then coverslipped with Cytoseal-60.

Fluorescent photomicrographs were collected on a Nikon 80i microscope with a QImaging QIClick cooled camera.

Statistics and Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). Non-parametric data and data that failed tests of normality (e.g., seizure severity, seizure frequency, seizure count) were analyzed using Wilcoxon Matched Pairs test for paired data or rank-transformed t-test. Parametric data (e.g., GBL experiments) were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. Unless otherwise noted, all GBL experiments passed the normality test and were analyzed using paired t-tests or ANOVA.

For population data (i.e., the proportion of animals displaying a particular seizure response), Fisher’s exact test (one-tailed) was used. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<0.05. One-tailed tests were used for seizure severity and population data because of our strong a priori hypothesis that collicular activation would suppress seizures, a hypothesis based on several decades of work (albeit with methods using lower spatiotemporal and cell-type precision). Two-tailed tests were used for other parameters (e.g., latency to seizure onset) as we did not have a priori hypotheses regarding these parameters.

Power spectra were generated essentially as previously described (Forcelli et al., 2012b). The FFT size was 1024 with a Hamming window and 93.75% window overlap. Power (V2) was plotted on a heat map showing time and frequency using LabChart 8.

Results

Histological Verification of Virus Injection

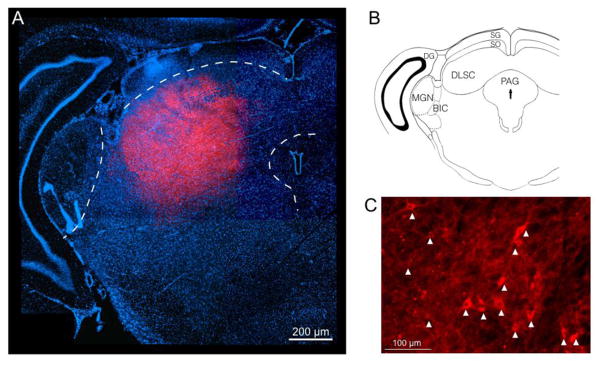

Histological confirmation of virus expression within DLSC is shown in Fig 1. mCherry fluorescence shows representative targeting of virus to the lateral superior colliculus. As shown in Fig 1a, the zone of virus expression is limited to the deep layers and avoids neighboring structures such as the medial geniculate and periaqueductal grey. Additional specificity is drawn from the fact that the fiber optic was placed within the deep/intermediate layers, and, as light is distributed ventrally from the tip of the fiber optic. Thus, activation of the superficial layers is unlikely to contribute to the effects we describe. Fig 1C shows individual neuronal somata within the DLSC labeled with mCherry, indicating virus infection.

Figure 1. Histological confirmation of virus infection within the DLSC.

A. Montage fluorescent photomicrograph showing the midbrain with the superior colliculus. DAPI=blue, mCherry=red. The zone of virus infection can be seen in the deep layers targeted to the lateral SC, avoiding the superficial layers, periaqueductal grey, and medial geniculate (each outlined in white). B. Atlas plane showing the slice presented in A. C. High power magnification showing labeled cell bodies within the DLSC. Arrow heads indicate ChR2-mCherry positive cells.

Effect of DLSC stimulation on seizures evoked by pentylenetetrazole

We first examined the ability of optogenetic activation of DLSC to attenuate seizures evoked by systemic administration of PTZ. Seizures evoked by PTZ include thalamocortical (spike-and-wave), forebrain (clonic) and hindbrain (tonic) components; because of this broad coverage of seizure types it was selected as our first model for investigation.

As shown in Figure 1A, under control (no stimulated) conditions animals displayed a median seizure severity of 4, corresponding to facial and forelimb clonus with rearing. When the same animals were tested with 100 Hz optogenetic stimulation, the median seizure response was a 2, corresponding to multiple myoclonic jerks. Wilcoxon’s test revealed a significant attenuation of seizure severity with 100 Hz stimulation, as compared to within-subject sham-stimulated control sessions (Fig 2A, P=0.0010). The latency to onset of seizure responses (typically myoclonic jerks) did not vary as a function of treatment (Fig 2B, t-test, t=0.45, P=0.66).

When we analyzed the prevalence of limbic motor seizure responses, we found that optogenetic stimulation protected a significant proportion of animals from PTZ-induced forebrain seizures (Fig 2C, P=0.0003, Fisher’s Exact Test). Moreover, when we examined the prevalence of tonic PTZ seizures (e.g., body twist or roll, tonic extension of the forelimbs), we likewise found that a significant proportion of animals were protected from this seizure manifestation by optogenetic stimulation (Fig 2D, Fisher’s Exact Test, P=0.020).

To determine if a stimulation frequency lower than 100 Hz would be sufficient to attenuate PTZ seizures, we next tested a group of rats using 5 Hz delivery of light. As shown in Fig 2E, optogenetic stimulation significantly (P=0.03, Wilcoxon’s test) reduced the median seizure score to 2 from 4.5 under baseline conditions. All animals displayed limbic motor seizure responses during baseline sessions, whereas only 33.3% did so when 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation was provided (Fig 2F; Fisher’s Exact Test, P=0.0303). As with 100 Hz stimulation, 5 Hz stimulation did not alter the latency to seizure onset (t test, P=0.46).

Controls for site-specificity and non-specific effects of light delivery

Post-mortem histological analysis revealed three animals from this experiment in which virus injections/fiber optic placement encroached on the inferior colliculus (IC). We analyzed these animals separately as a measure of site specificity within the dorsal midbrain. When virus was misplaced in this site, seizures were not attenuated by optogenetic stimulation, and in fact, in two of the three rats, seizure severity increased (Fig 2G). This is consistent with an established role for IC in the genesis of brainstem seizures (Millan et al., 1986).

To rule out non-specific effects of our optogenetic manipulations, we next injected animals with a control vector (AAV-hSyn-HA-hM4D(Gi)-ires-mCitrine). This vector does not produce a light-sensitive ion channel. Thus light delivery should be without effect. When we delivered light to rats injected with this vector at 100 Hz there was no change in seizure severity as compared to within-subject baseline sessions (P=0.88, Wilcoxon test 2-tailed, Fig 2H). This differs dramatically from the anticonvulsant effect produced in animals expressing ChR2 (Fig 2A). Similarly, delivery of unmodulated light to animals with the control vector (which was selected to represent a “worst case scenario” with respect to heating) did not attenuate seizures (Fig 2I, Wilcoxon test, 2-tailed, P=0.813). These data rule out non-specific effects of light delivery and/or tissue heating.

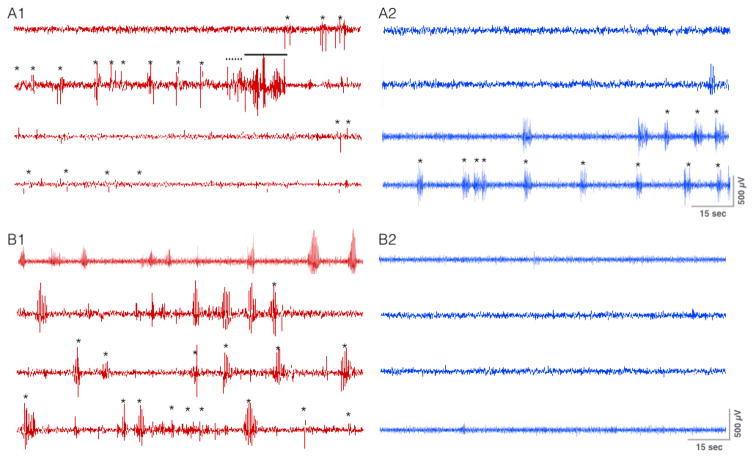

Effect of optogenetic stimulation of DLSC on electrographic seizure activity evoked by PTZ

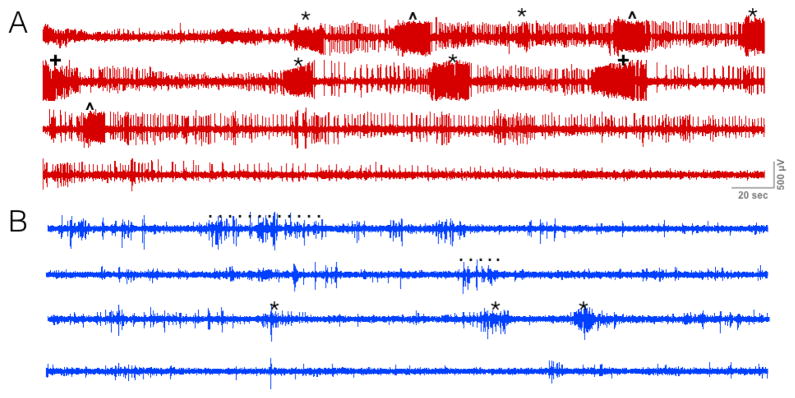

We measured the ability of DLSC stimulation to inhibit electrographic seizures in a subset of SD rats (n=5). Figure 3 shows the electrographic seizure response in two representative SD rats tested with and without 100 Hz optogenetic stimulation of DLSC. Fig 3A1 shows tonic-clonic electrographic discharges associated with running bouncing seizures in a rat that did not receive optogenetic stimulation. When the same rat was tested with 100 Hz stimulation, only myoclonic jerks were evident behaviorally, and brief discharges co-occurring with the jerks were evident electrographically (Fig 3A2). Fig 3B1 shows electrographic seizures associated with facial clonus and myoclonic jerks when tested in the absence of optogenetic stimulation. When tested with 100 Hz stimulation, both electrographic and behavioral seizures were completely suppressed (Fig 3B2). Note that of the five SD rats tested, one animal displayed electroclinical uncoupling of seizures (i.e., no behavioral seizures, but brief electrographic discharges). Electroclinical uncoupling was selected against (i.e., did not occur) under baseline conditions, as all animals were titrated to display overt behavioral seizures prior to initiating optogenetic testing.

Figure 3. Optogenetic activation of DLSC attenuates electrographic seizure response to pentylenetetrazole.

A1. Single subject treated with PTZ in the absence of optogenetic stimulation, * = myoclonic jerk, dashed line = clonic seizure response, solid line = tonic seizure response. A2. Same subject treated with the same dose of chemoconvulsant and 100 Hz optogenetic stimulation. Note the absence of clonic or tonic electrographic activity. Only brief spike-wave discharges were present co-occuring with facial clonus or myoclonic jerks (*). B1. A second subject treated with PTZ alone; behavioral response was limited to facial clonus/myoclonic jerks (*). B2. The same subject treated with the same dose with 100 Hz optogenetic stimulation. Both the behavioral and electrographic seizure manifestations were completely abolished.

To minimize the possibility that behavioral-electrographic uncoupling of seizures was responsible for the effect we detected, we re-analyzed the behavioral seizure data excluding animals that showed complete abatement of behavioral seizures during optogenetic testing (n=4 of 15). We found that optogenetic activation of DLSC significantly suppressed seizure severity (Wilcoxon test, P=0.015). Thus, behavioral-electrographic uncoupling of seizure responses cannot account for the seizure suppressive effect we describe.

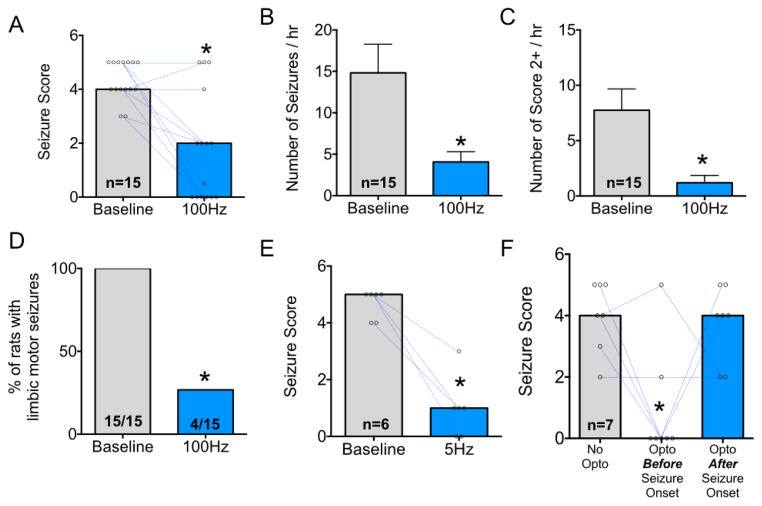

Effect of DLSC stimulation on seizures evoked from Area Tempestas

To examine the ability of optogenetic activation of DLSC to attenuate seizures evoked from a discrete and defined locus that results in seizures confined to the forebrain limbic seizure network, we turned to focal pharmacological activation of AT within piriform cortex (Gale et al., 1992; Piredda and Gale, 1985). Microinjection of picomole amounts of bicuculline methiodide into this site evokes repeated limbic motor seizures. Moreover, seizures evoked from this site have face and construct validity across a variety of species, including rats (Gale et al., 1992; Piredda and Gale, 1985), nonhuman primates (Gale and Dubach, 1993), and humans (Laufs et al., 2011). Optogenetic stimulation began immediately after bicuculline infusion into AT.

Under baseline (no stimulation) conditions, animals displayed a median seizure severity of 4, corresponding to facial and forelimb clonus with rearing. When optogenetically stimulated at 100 Hz, the median seizure severity was 2, corresponding to brief clonus of the face and/or contralateral forelimb. Wilcoxon test revealed that optogenetic stimulation significantly suppressed the severity of seizures in these rats (P=0.0007, Fig 4A).

Figure 4. Optogenetic activation reduces the severity and frequency of seizures evoked from Area Tempestas.

A. Median seizure score with points and lines indicating baseline-to-stimulated (100 Hz) changes in seizure severity. B. Mean (+SEM) number of seizure manifestations per hour (Score of 0.5 or greater). C. Mean (+SEM) number of limbic seizures per hour (Score of 2 or greater). D. Proportion of animals with limbic motor seizure responses (Score of 3 or greater). E. Median seizure severity under baseline and 5 Hz stimulation conditions. F. Median seizure severity either: without optogenetic sitmulation, with optogenetic stimulation applied before behavioral seizure onset, or with optogenetic stimulation (100 Hz) applied after behavioral seizure onset. * = P<0.05.

Seizures evoked from AT occur in clusters over ~1 hour. The median number of discrete seizure manifestations (e.g., jaw clonus or greater) observed in baseline sessions was 11/hr. When animals were optogenetically stimulated, the mean number of seizure manifestations fell to 2.5/hr. Wilcoxon test revealed a significant suppression of seizure number in response to optogenetic stimulation (W=−118, P=0.0001, Fig 4B). When we analyzed the frequency of more severe motor responses (i.e., facial+forelimb clonus, Score 2), we found a similar pattern of suppression (Fig 4C). Under baseline conditions, the median number of limbic motor seizures was 5. By contrast, when tested with optogenetic stimulation the median was 0 (Wilcoxon test, W = −105, P=0.0007). Consistent with this finding, Fisher’s exact test revealed that optogenetic activation of DLSC protected a significant proportion of animals from limbic motor seizure responses (P<0.0001, Fig 5D).

Figure 5. Optogenetic activation of SC reduces electrographic manifestations of Area Tempestas-evoked seizures.

A. Single subject with AT-evoked seizure in the absence of optogenetic stimulation, * = prolonged bilateral forelimb clonus, ^ = with rearing, + = with loss of balance. B. Same subject treated with the same dose of chemoconvulsant and 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation. The dotted lines indicate motion artifact while untangling a cable.

As in the PTZ model, we next examined the ability of lower-frequency activation of DLSC to attenuate seizures (Fig 2E). Under baseline (no stimulation) conditions, the median seizure score was 5 and all animals displayed limbic motor seizure responses. Optogenetic stimulation reduced the median seizure score to 1 and protected 83.3% of animals from limbic motor seizures. These effects reached the level of statistical significance (Wilcoxon test, P=0.0156 and Fisher’s Exact Test, P=0.024, respectively).

Seizures evoked from AT provided us with an ideal model to determine if DLSC activation would be effective after seizure onset. For this purpose, we tested seven rats with 100 Hz stimulation of DLSC both prior to seizure induction and after the first behavioral manifestation of seizure activity (myoclonic jerks, facial clonus). Interestingly, we found that while pretreatment was highly effective at attenuating seizure activity, treatment after the first behavioral manifestation was not (Fig 4F). When animals were tested without optogenetic stimulation, the median seizure score was 4, when optogenetic stimulation was delivered prior to seizure initiation it was 0, and finally, when stimulation was started after seizure initiation the median severity was 4. Only the pre-treatment and control groups differed from one another (Kruskal Wallis test, P=0.016).

To confirm that our manipulations were reducing both electrographic and behavioral seizure manifestations, we recorded cortical EEG from a subset of rats with AT seizures at 5 Hz stimulation. Figure 5 shows a representative cortical EEG from a rat during a test session without (red trace, 5A) and with (blue trace, 5B) optogenetic stimulation. When tested without optogenetic stimulation, the animal displayed multiple Stage 4/5 seizures; when tested with optogenetic stimulation, this animal displayed repeated unilateral forelimb clonus with occasional brief bilateral forelimb clonus. This is evident in the electrographic trace, which shows nine high frequency electrographic seizures with intermittent spiking in between ictal events during the baseline session. During the session with 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation, only 3 ictal discharges were observed and these were of lower amplitude. Moreover, the frequency of spiking appeared to be reduced between these events. All animals we recorded from showed a suppression in electrographic seizure activity with optogenetic stimulation.

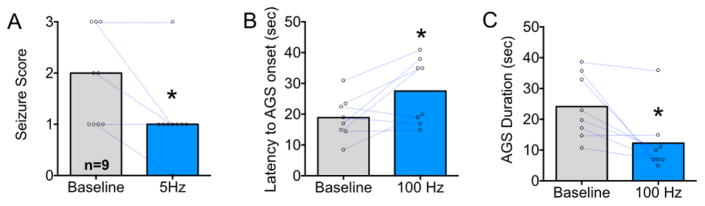

Effect of DLSC stimulation on audiogenic seizures in genetically epilepsy-prone rats

We use the GEPR-3 to determine if focal activation of DLSC would attenuate seizures evoked in an inherited model of epilepsy. Seizures in GEPR-3s are primary brainstem seizures characterized by WR that developed into bouncing clonus. GEPR-3s (n=9) were tested for seizures in response to acoustic stimulation with and without 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation of DLSC. We found that optogenetic stimulation significantly suppressed the occurrence of clonus but did not alter the prevalence of wild running (P=0.0076, Fisher’s Exact Test). During baseline test sessions, 7 of 9 (77.7% of animals) displayed clonus, while when tested with 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation only 1 of 9 (11.1%) displayed clonus. We also found that the median seizure severity was significantly (P=0.03, Wilcoxon test, Fig 6A) reduced by optogenetic stimulation. Moreover, the latency to onset was significantly increased by stimulation (P=0.016, Wilcoxon test, Fig 6B) and the duration of audiogenic seizure was significantly decreased (P=0.04, t-test, Fig 6C). Thus, as with the PTZ model, optogenetic activation of DLSC was able to suppress brainstem seizure responses.

Figure 6. Optogenetic activation of DLSC attenuates audiogenic seizure responses in GEPR-3 rats.

A. Median audiogenic seizure severity with points and lines indicating changes in seizure severity comparing baseline to 5 Hz stimulation. B. Mean latency to onset of audiogenic seizure. C. Mean duration of audiogenic seizure. * = significantly different than baseline, P<0.05; Wilcoxon Test (Panel A); P<0.05, t-test (Panel B and C).

Effect of DLSC stimulation on seizures evoked by gamma butyrolactone

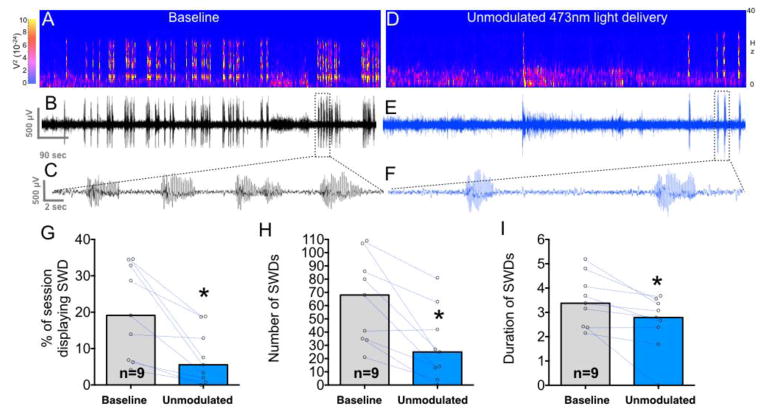

We next examined a model of electrographic seizures originating in the thalamocortical network evoked by systemic administration of gamma butyrolactone (Depaulis et al., 1989; Snead, 1991, 1990, 1982; Snead et al., 1999). We first examined the effect of unmodulated stimulation to mirror previous studies using focal drug administration (i.e., in prior studies, infusion of GABA antagonist “activated” DLSC, but did not allow for the control of the frequency/pattern of activation).

Under control conditions, rats displayed a mean cumulative duration of spike-and-wave discharges (SWDs) of 241 sec. These are evident as high-amplitude 7 Hz bursts on the electrographic trace and spectrogram shown in Fig 7A–C. When treated with unmodulated optogenetic stimulation of DLSC, this was reduced to a mean of 92 sec (compare Fig 7A–C to Fig 7D–F). This suppression in SWDs by unmodulated optogenetic stimulation is quantified in Fig 7G as percent of the observation period exhibiting SWDs (t=3.8, df=8, P=0.0054). This seizure-suppressive effect was also evident on other measures of SWDs, including the number of discharges (t=4.18, df=8, P=0.0031, Fig 7H) and the average discharge duration (t=3.3, df=8, P=0.011, Fig 7I).

Figure 7. Unmodulated light delivery suppresses spike-and-wave discharges evoked by gamma butyrolactone.

A. Spectrogram showing power as a function of frequency and time after an injection of gamma butyrolactone. B. Corresponding electrographic trace to the spectrogram in A. Seizures (spike-and-wave discharges) are clearly visible above background and are shown with an expanded timescale in C. D. Spectrogram from the same rat as in Panels A–C showing an attenuation of seizures in response to gamma butyrolactone when coupled with unmodulated delivery of blue light. E. Electrographic trace corresponding to the spectrogram shown in D; a section of this trace [indicated by the dotted box] is shown with an expanded timescale in F. G. Mean percent of the session showing SWDs when animals were tested with unmodulated blue light delivery as compared to baseline. Dots and lines show changes in individual animals comparing baseline to unmodulated Hz light delivery. H. Mean number of SWDs during the observation period. I. Mean average duration of individual SWDs. * = P<0.05.

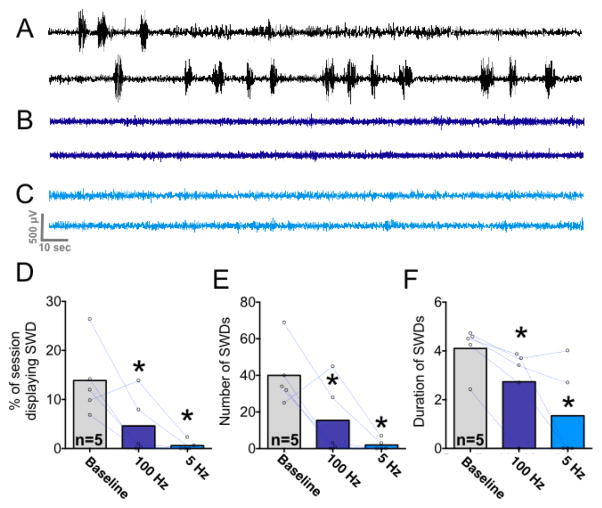

To determine if patterned activation of DLSC would exert a similar effect, we next examined the ability of 5 Hz and 100 Hz stimulation to attenuate SWDs (Fig 8). Under control (baseline) conditions, animals spent a mean of 166 sec exhibiting SWD; when stimulated at 100Hz this was reduced to 55 sec, and when stimulated at 5 Hz this was reduced to 7 sec. This is evident in both the electrographic traces (from a single subject across the three test sessions) shown in Fig 8A–C and when quantified across animals in Fig 8D–F. Analysis of variance revealed a significant main effect of stimulation (i.e., no stimulation vs. 100 Hz, vs 5 Hz) on the percent of the observation period spent exhibiting SWDs (F1.58,6.32=8.81 P=0.018). Post-hoc tests (Holm-Sidak corrected, one-tailed) demonstrated a significant suppression of SWDs by both 5 Hz and 100 Hz stimulation (Fig 8D). We did not compare differences between 100 Hz and 5 Hz stimulation, as we had not planned to examine this a priori and the study is not powered to detect differences in magnitude of treatment effects. However, this merits examination in the future.

Figure 8. Pulsed light delivery is highly effective at suppressing spike-and-wave seizures.

A. Electrographic trace of a rat after administration of gamma butyrolactone in the absence of optogenetic stimulation. B. The same animal with 100 Hz optogenetic stimulation. C. The same animal with 5 Hz optogenetic stimulation. D. Mean percentage of observation period showing spike-and-wave discharges. Dots and lines show changes in individual animals comparing baseline to 100 Hz and 5 Hz light delivery. E. Mean number of discharges observed during the test session. F. Mean duration of individual spike-wave discharges. * = P<0.05 as compared to within-subject baseline control session; Holm-Sidak (one-tailed) corrected for multiple comparisons.

Stimulation not only suppressed the percent of the observation period displaying SWDs, but also the number of discharges observed (F1.54,6.16=8.9, P=0.018); multiple comparisons tests revealed that this reached the level of significance for both 100 Hz and 5 Hz stimulation conditions (Fig 8E). Patterned stimulation also reduced the average discharge duration (data did not meet the assumption of normality and were thus analyzed using Friedman’s test; χ2(3)=8.3, P=0.0077). Post-hoc tests (Dunn’s one-tailed test) revealed that this reached the level of statistical significance for both 5 Hz and 100Hz stimulation conditions (Fig 8F).

Finally, to determine if optogenetic stimulation of DLSC evoked behavioral changes similar to those reported with pharmacological or electrical activation, we examined the effects of unilateral optogenetic stimulation (100 Hz) in six SD rats with correct placement of virus and fiber optic within DLSC. Unilateral stimulation was selected based on prior reports of movements induced by unilateral electrical and chemical stimulation of SC. Two of the 6 animals displayed contraversive posturing in response to unilateral stimulation, an additional 2 SD rats displayed freezing and/or a startle response, and the remaining 2 animals displayed no overt behavioral response to DLSC activation. All six of these animals displayed seizure suppression. With bilateral stimulation, we did not observe overt changes in behavior in animals tested across seizure models.

Discussion

The goals of the present study were three-fold: 1) to test the hypothesis that optogenetic activation of DLSC would exert anticonvulsant effects against forebrain, hindbrain, and thalamocortical seizures, 2) to characterize DLSC seizure control using the same procedures, coordinates, and manipulations across four seizure models, and 3) to examine frequency-dependent and timing-dependent effects of SC activation that were impossible to examine using microinjection methods. We have shown that optogenetic activation of the DLSC suppresses seizure activity in four seizures models: forebrain+hindbrain seizures evoked by PTZ, forebrain seizures evoked focally from AT, hindbrain seizures in GEPR-3s, and thalamocortical seizures evoked by GBL. Behavioral and electrographic seizure manifestations were both attenuated by SC activation. These effects were specific to stimulation of the deep and intermediate layers of SC, and cannot be explained by non-specific effects of optogenetics (e.g., heating).

SC activation suppresses PTZ seizures

The present study is the first to demonstrate suppressive effects of DLSC activation against convulsive seizures evoked by PTZ, which engages both forebrain and hindbrain seizure networks to model secondarily generalized seizures. Our findings contrast with a prior report which showed a potentiation of seizure responses evoked by PTZ and intravenous bicuculline in response to pharmacological activation of SC (Weng and Rosenberg, 1992). The prior report, however, may have been complicated by the dual application of systemic chemoconvulsant and focal GABA blockade.

Both behavioral and electrographic PTZ seizure manifestations were attenuated by optogenetic stimulation. At the doses we employed, PTZ seizures typically begin with forebrain manifestations (e.g., facial/forelimb clonus) before propagating to the hindbrain (e.g., tonic/clonic features). Optogenetic stimulation of DLSC suppressed both forebrain and hindbrain components of PTZ seizures. These findings suggest that activation of DLSC may attenuate propagation of seizure activity from the forebrain to the hindbrain. Another possibility is that DLSC activation may raise the threshold for forebrain seizure initiation. Indeed, the behavioral and electrographic data are similar to what would be expected from a right-shifted dose-response function for PTZ.

SC activation suppresses Area Tempestas seizures

Optogenetic activation of DLSC significantly suppressed both the severity and frequency of seizures evoked from AT. A significant proportion of animals were protected from limbic motor seizure responses (characterized by facial and forelimb clonus with rearing). These seizure manifestations are the rodent equivalent of complex partial seizures in humans, with a sub-threshold response (i.e., isolated facial clonus) representing a simple partial seizure response. This pattern of protection in rodents is consistent with that reported by Gale and colleagues using focal pharmacological activation of SC (i.e., a protection from clonic seizures) (Gale et al., 1993), suggesting an inhibitory effect of SC activation on seizure propagation within the forebrain network. In the current study, we also found that the frequency of seizure occurrence was also reduced by DLSC activation. Surprisingly, we found that activation of DLSC after the onset of a behavioral seizure was ineffective at attenuating the seizure response during the same ictal event. Together, these data suggest that DLSC may regulate the threshold for initiation of discrete forebrain ictal events, showing efficacy at attenuating seizures if activated prior to behavioral seizure onset, but not after behavioral manifestations have become evident. The degree to which early intervention (e.g., at the first sign of electrographic seizure activity, a closed loop system) would allow for SC-induced termination of forebrain seizures remains a high priority for future examination.

SC activation suppresses audiogenic seizures in GEPRs

Reports of seizure suppressive effects evoked from superior colliculus in audiogenic rat models have produced conflicting results. Many studies have reported that prototypical AGS responses can be evoked by activation of SC, and that blockade of glutamatergic transmission in SC can attenuate audiogenic seizures (Browning et al., 1999; A. Depaulis et al., 1990; Doretto et al., 2009; Faingold and Casebeer, 1999; Faingold and Randall, 1999; Merrill et al., 2003; Raisinghani and Faingold, 2003; Rossetti et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2001). In parallel, there have been reports that activation of SC can attenuate audiogenic seizure responses (Merrill et al., 2003). In this latter report, the severity of AGS was significantly attenuated by bicuculline microinjection in SC with 20–30% of animals displaying AGS-like responses to bicuculline infusion alone. While Merrill and colleagues (2003) suggest that the suppression of seizures by DLSC may be due to post-ictal refractoriness, we find this to be unlikely given our current results -- we found significant suppression of AGS seizure manifestations (increased latency, decreased severity, decreased duration) in 9 of 10 animals that did not display overt AGS-like responses to optogenetics alone. The one remaining GEPR exhibited an AGS-like running response to 5 Hz stimulation, which was behaviorally-locked to the onset and offset of optogenetic activation. Histological analysis of this animal revealed that the center of virus injection ventral to the DLSC, in the vicinity of the inferior colliculus and intracollicular nucleus, raising the possibility that virus spread (in our study) or drug spread (in other studies) may account for seizure initiation and wild running responses.

The DLSC is thought to play an important role in the generation of the WR component of AGS in the GEPR (Faingold and Randall 1999), whereas clonus is thought to be driven by the pontine reticular formation/periaqueductal grey (Faingold, 1999). These suggestions are based on the firing properties of neurons in SC and pontine reticular formation/periaqueductal grey, which enter tonic firing phases immediately before the emergence of wild running and clonus, respectively. In the present study, we found that optogenetic stimulation of DLSC primarily impacted the occurrence of clonus, not WR. This suggests that while SC activity may be necessary for some aspects (WR) of audiogenic seizures in GEPRs, it may also be exploited to suppress clonic seizure manifestations in these animals. Given the importance of SC in the genesis of WR, it is perhaps unsurprising that WR was not attenuated with our stimulation. However, it is not clear that the same neurons needed for the genesis of WR are those that are implicated for seizure suppression; indeed, activation of the medial, but not lateral SC generates explosive escape behaviors (Sahibzada et al., 1986), including running and jumping, whereas lateral SC is needed for seizure control effects (Dean and Gale, 1989; Gale et al., 1993; Shehab et al., 1995a). Furthermore, the neurons recorded by Faingold and Randall (Faingold and Randall, 1999) that burst-fire at the onset of WR are located in the medial SC.

SC activation suppresses absence seizures

We observed a pronounced seizure-suppressive effect against thalamocortical spike-and-wave seizures, consistent with prior reports (A Depaulis et al., 1990a, 1990b; Nail-Boucherie et al., 2002; Redgrave et al., 1988). This seizure suppression indicates a role for DLSC in regulating the initiation of these seizures, even though the site of initiation is distal to the SC (i.e., in the thalamus). This finding is consistent with reports of anti-seizure effects of collicular activation in genetically absence prone rats (A Depaulis et al., 1990a; Nail-Boucherie et al., 2002), as well as in evoked absence seizure models (Redgrave et al., 1988).

This seizure-disruptive effect of DLSC stimulation against absence-like seizures is consistent with our findings in the GEPR-3s, where seizure duration was also significantly suppressed by optogenetic activation. These data suggest that DLSC may exert a seizure disruptive effect, even after a discharge is initiated. Interestingly, data from these two models contrast with our finding in the AT model. In the latter case, SC activation was ineffective at suppressing a seizure once an event had been initiated. This raises the possibility that different downstream mechanisms or circuits may mediate anti-seizure effects against forebrain, as compared to hindbrain and thalamocortical seizures.

Frequency-dependent effects of SC activation

Unlike prior studies employing pharmacological activation of superior colliculus (Dean and Gale, 1989; A Depaulis et al., 1990a; Gale et al., 1993; Garant and Gale, 1987; Redgrave et al., 1992, 1988; Shehab et al., 1995a), we were able to modulate the frequency of activation of DLSC. We found that activation of DLSC at frequencies as low as 5 Hz was sufficient to suppress seizure activity. While one prior study has examined electrical activation of DLSC (25 Hz) against seizures in genetically absence epileptic rats from Strasbourg (Nail-Boucherie et al., 2002), electrical stimulation only produced a transient suppression of seizure activity (Nail-Boucherie et al., 2002). By comparison, our manipulation suppressed activity throughout the observation period, even at lower stimulation rates. Low frequency stimulation (as compared to high frequency DBS which can induce depolarization block) may allow for a greater degree of normal signaling to occur and merits investigation as a method for reducing cognitive side effects associated with DBS. Based on the data in a recent report regarding optogenetic induction of depolarization block, it seems unlikely that our 5 Hz stimulation would trigger such an effect (Herman et al., 2014).

The profile of seizure suppression with 5 Hz and 100 Hz stimulation merits further discussion. First, suboptimal stimulation with 100 Hz light delivery is unlikely to account for any differences. Channel inactivation in response to constant light delivery is low for ChR2(H134R) (Berndt et al., 2011), and several groups have reported that ChR2(H134R) can drive spiking with stimulation rates up to 100 Hz. Indeed, even unmodulated stimulation has been shown to induce prolonged and regular spiking (Grossman et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011). However, while 5 Hz stimulation can drive neurons with near-perfect spike fidelity, higher stimulation rates have spike fidelity ranging from 20 – 50% (Berndt et al., 2011; Cardin et al., 2010; Nakamura et al., 2012). Even assuming that we achieved the lower end of this range of spike fidelity with 100 Hz stimulation, we would still be driving activity at frequencies greater than those achieved with 5 Hz stimulation. One particularly compelling, but speculative, possibility is that higher stimulation frequencies increase the ratio of inhibitory to excitatory cells recruited by stimulation. This might be expected, as more than half of the inhibitory neurons within the superior colliculus are fast spiking interneurons, capable of sustained firing at frequencies of up to 100 Hz (Sooksawate et al., 2011).

Behavioral effects of SC activation

Both pharmacological and electrical activation of DLSC can produce postural and behavioral responses (Comoli et al., 2012; Dean et al., 1986; DesJardin et al., 2013; Holmes et al., 2012; Redgrave et al., 1981; Sahibzada et al., 1986). In none of the animals tested did we detect overt defense responses (e.g., explosive escape behaviors). This is likely a result of our selective targeting of the lateral SC, which has been associated with approach responses (as compared to the defensive responses evoked from the medial SC) (Comoli et al., 2012; Dean et al., 1989). However, the fact that we only evoked orienting in 2 of 6 animals tested with unilateral stimulation suggests that the pattern of spread of activation may also be a critical determinant of the behavioral response. Stationary objects within the visual field are unlikely to represent either predator or prey. Prey for a rat (e.g., a cockroach) skitters across the lower visual field (represented topographically in the lateral SC) (Favaro et al., 2011). Threat for a rat (e.g., a hawk looming from above) progressively occupies more of the upper visual field (represented in the medial SC) as it swoops towards the rat. It is possible that by avoiding spread of activation seen with other stimulation methods, the stationary location of activation failed to engage either approach or avoidance responses.

Potential circuit mechanisms for broad-spectrum seizure control

Our present results build on an extensive literature suggesting a role for DLSC in the control of seizures. A role for DLSC was first suggested based on its interconnections with the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr) in the suppression of maximal electroshock seizures (Dean and Gale, 1989; Garant and Gale, 1987). Indeed, lesions to the DLSC disrupt the potent anticonvulsant effects evoked by pharmacological inhibition of SNpr (Garant and Gale, 1987), while pharmacological activation of the DLSC potently suppresses seizures in the maximal electroshock model (Redgrave et al., 1992; Shehab et al., 1995a). Our present findings underscore a promising role for the SC in treatment of seizures.

The zone in which our virus was placed is the lateral, deep layers of the SC, in the vicinity of a region described by Shehab, Redgrave and colleagues as the “dorsal midbrain anticonvulsant zone” (DMAZ, although it is worth noting that our injections encompass only the dorsal aspect of this region, and not ventral regions such as the intracollicular nucleus) (Redgrave et al., 1992; Shehab et al., 1995a, 1995b). Redgrave and Dean have previously reported that electrical or chemical stimulation of this region can desynchronize the cortical EEG (Dean et al., 1991; Redgrave and Dean, 1985). The cortical desynchronization caused by SC activation may provide a mechanism by which focal activation of DLSC can suppress distal cortical seizure manifestations. However, the circuit mechanisms mediating desynchronization and seizure suppression remain obscure.

How can a focal motor control region, such as the SC, exert such broad-spectrum seizure suppressive effects? Several possibilities exist, each of which is a target of ongoing studies in our laboratory. First, DLSC may project to a single site that mediates anticonvulsant effects. For example, the DLSC has strong descending connections to the pontine reticular formation (Redgrave et al., 1987a; Shehab et al., 1995b), including to the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN). The PPN in turn has ascending cholinergic projections to the thalamus and, through a relay in the basal forebrain, can also trigger cortical cholinergic transmission (Dringenberg and Olmstead, 2003; Garcia-Rill et al., 2001; Kleiner and Bringmann, 1996; Rasmusson et al., 1994; Saper and Loewy, 1982; Semba and Fibiger, 1992; Ulloor et al., 2004; Vertes et al., 1993; Woolf and Butcher, 1986). In addition, PPN has descending cholinergic projections to a critical site for the initiation of tonic seizures, the nucleus reticularis pontis oralis. These projections are anatomically and neurochemically well-suited to attenuate seizures, as application of cholinergic agonists to thalamus and the nucleus reticularis pontis oralis (NPRO) both attenuate seizures (Danober et al., 1995; Peterson, 1993). In addition, the PPN has recently been examined in the context of loss of consciousness during focal limbic seizures; partial limbic seizures suppress neuronal firing within the PPN (Motelow et al., 2015), while optogenetic stimulation of these neurons during limbic seizures normalizes cortical slowing seen with focal hippocampal seizures (Furman et al., 2015). These data are consistent with a role for PPN in regulating seizure phenotypes.

Secondly, DLSC may exert its anticonvulsant effects through direct projections to each of the independent seizure networks. SC has strong projections to the thalamus, including intralaminar and midline regions associated with seizure control (Krout et al., 2001), as well as projections to amygdala mediated by pulvinar (Linke et al., 1999). Similarly, SC has strong descending projections to brainstem seizure circuitry, including direct projections to the NPRO (Redgrave et al., 1987a). The efferent connections of the SC have a well-described topology: the DMAZ/lateral DLSC send robust projections to the pons, whereas medial regions of SC referentially target the cuneiform nucleus (Redgrave et al., 1987b). Likewise, projections from the SC to the intralaminar/midline thalamus also preferentially arise from the lateral SC (Krout et al., 2001). Both of these outputs are well positioned to disrupt synchronized activity throughout the brain.

The segregation between effective sites in the SC (i.e., targeting lateral SC/DMAZ is necessary for seizure control) strongly suggests that pathways originating in the lateral SC play an important role. However, within the DLSC, the role of specific projections remains obscure. While the data we present here cannot distinguish between populations of neurons that project to pons versus thalamus, they provide the first step towards unraveling this puzzle. Our study lays the foundation for future investigations examining the role of descending projections from DLSC to the pons, and ascending projections from DLSC to the thalamus in seizure control.

Conclusions

Here we have validated optogenetic activation of DLSC as a promising target for therapeutic intervention. We found suppression of behavioral and electrographic seizures, and these effects were apparent against seizures originating in the forebrain, hindbrain, and thalamocortical seizure networks. Effects included suppression of seizure initiation and seizure propagation, as well as enhanced seizure termination. In light of the therapeutic achievements using deep brain stimulation in basal ganglia nuclei to treat movement disorders (Bronstein et al., 2010), as well as observations in patients with epilepsy (Gale, 2004; Loddenkemper et al., 2001; Luders, 2004; Luders and Comair, 2001), there is considerable hope that focal stimulation of basal ganglia structures may prove effective for the treatment of epilepsy. Our present findings suggest that selective, temporally-controlled activation of DLSC can be utilized to achieve broad-spectrum seizure control.

Highlights.

Optogenetic activation of DLSC suppressed seizures evoked by pentylenetetrazole

Optogenetic activation of DLSC suppressed Area Tempestas-evoked forebrain seizures

Optogenetic activation of DLSC suppressed thalamocortical seizures

Optogenetic activation of DLSC suppressed brainstem seizures in a genetic rat model

Seizure suppression was effective at frequencies as low as 5 Hz

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the late Dr. Karen Gale, a long-time friend and mentor. Her landmark studies of the role of basal ganglia in seizure control provided the inspiration for these experiments. We are grateful for the technical advice provided by Dr. Ed Boyden and Dr. Xue Han, to Samuel Gutherz for assistance with histology and Veronica Beck for assistance with seizure testing. This research was supported by pilot grants from the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1TR000101; UL1TR001409), a grant from the Georgetown University Medical Center Dean for Research, and a grant from the American Epilepsy Society/Epilepsy Foundation of America to PAF. PAF received support from HD046388 and KL2TR001432 and PN from AA020073, all from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Designed Experiments/Supervised Research: PAF

Conducted Experiments: CS, CVK, EW, PN, PAF

Analyzed Data: CS, EW, PN, PAF

Wrote Paper: CS, CVK, EW, PN, PAF

Obtained Funding: PAF, PN

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bergstrom RA, Choi JH, Manduca A, Shin H-S, Worrell GA, Howe CL. Automated identification of multiple seizure-related and interictal epileptiform event types in the EEG of mice. Sci Rep. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/srep01483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A, Schoenenberger P, Mattis J, Tye KM, Deisseroth K, Hegemann P, Oertner TG. High-efficiency channelrhodopsins for fast neuronal stimulation at low light levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7595–7600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017210108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M, Singer W, Engel AK. Patterns of synchronization in the superior colliculus of anesthetized cats. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1999;19:3567–3579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03567.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein JM, Tagliati M, Alterman RL, Lozano AM, Volkmann J, Stefani A, Horak FB, Okun MS, Foote KD, Krack P, Pahwa R, Henderson JM, Hariz MI, Bakay RA, Rezai A, Marks WJ, Moro E, Vitek JL, Weaver FM, Gross RE, Delong MR. Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson Disease: An Expert Consensus and Review of Key Issues. Arch Neurol. 2010 doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning RA, Wang C, Nelson DK, Jobe PC. Effect of precollicular transection on audiogenic seizures in genetically epilepsy-prone rats. Exp Neurol. 1999;155:295–301. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin JA, Carlen M, Meletis K, Knoblich U, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Tsai LH, Moore CI. Targeted optogenetic stimulation and recording of neurons in vivo using cell-type-specific expression of Channelrhodopsin-2. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:247–54. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy RM, Gale K. Mediodorsal thalamus plays a critical role in the development of limbic motor seizures. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1998;18:9002–9009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comoli E, Das Neves Favaro P, Vautrelle N, Leriche M, Overton PG, Redgrave P. Segregated anatomical input to sub-regions of the rodent superior colliculus associated with approach and defense. Front Neuroanat. 2012;6:9. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danober L, Depaulis A, Vergnes M, Marescaux C. Mesopontine cholinergic control over generalized non-convulsive seizures in a genetic model of absence epilepsy in the rat. Neuroscience. 1995;69:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00276-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Gale K. Anticonvulsant action of GABA receptor blockade in the nigrotectal target region. Brain Res. 1989;477:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Redgrave P, Sahibzada N, Tsuji K. Head and body movements produced by electrical stimulation of superior colliculus in rats: effects of interruption of crossed tectoreticulospinal pathway. Neuroscience. 1986;19:367–380. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Redgrave P, Westby GW. Event or emergency? Two response systems in the mammalian superior colliculus. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Simkins M, Hetherington L, Mitchell IJ, Redgrave P. Tectal induction of cortical arousal: evidence implicating multiple output pathways. Brain Res Bull. 1991;26:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90184-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Liu Z, Vergnes M, Marescaux C, Micheletti G, Warter JM. Suppression of spontaneous generalized non-convulsive seizures in the rat by microinjection of GABA antagonists into the superior colliculus. Epilepsy Res. 1990a;5:192–198. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90038-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Marescaux C, Liu Z, Vergnes M. The GABAergic nigro-collicular pathway is not involved in the inhibitory control of audiogenic seizures in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1990;111:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90273-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Snead OC, Marescaux C, Vergnes M. Suppressive effects of intranigral injection of muscimol in three models of generalized non-convulsive epilepsy induced by chemical agents. Brain Res. 1989;498:64–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Vergnes M, Liu Z, Kempf E, Marescaux C. Involvement of the nigral output pathways in the inhibitory control of the substantia nigra over generalized non-convulsive seizures in the rat. Neuroscience. 1990b;39:339–349. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Vergnes M, Marescaux C. Endogenous control of epilepsy: the nigral inhibitory system. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:33–52. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DesJardin JT, Holmes AL, Forcelli PA, Cole CE, Gale JT, Wellman LL, Gale K, Malkova L. Defense-like behaviors evoked by pharmacological disinhibition of the superior colliculus in the primate. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2013;33:150–155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2924-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doretto MC, Cortes-de-Oliveira JA, Rossetti F, Garcia-Cairasco N. Role of the superior colliculus in the expression of acute and kindled audiogenic seizures in Wistar audiogenic rats. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2563–2574. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dringenberg HC, Olmstead MC. Integrated contributions of basal forebrain and thalamus to neocortical activation elicited by pedunculopontine tegmental stimulation in urethane-anesthetized rats. Neuroscience. 2003;119:839–853. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybdal D, Gale K. Postural and anticonvulsant effects of inhibition of the rat subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6728–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06728.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold C, Casebeer D. Modulation of the audiogenic seizure network by noradrenergic and glutamatergic receptors of the deep layers of superior colliculus. Brain Res. 1999;821:392–399. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL. Neuronal networks in the genetically epilepsy-prone rat. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:311–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL, Randall ME. Neurons in the deep layers of superior colliculus play a critical role in the neuronal network for audiogenic seizures: mechanisms for production of wild running behavior. Brain Res. 1999;815:250–258. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro PDN, Gouvêa TS, de Oliveira SR, Vautrelle N, Redgrave P, Comoli E. The influence of vibrissal somatosensory processing in rat superior colliculus on prey capture. Neuroscience. 2011;176:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, Gale K. Brain Circuits Responsible for Seizure Generation, Propagation, and Control: Insights from Preclinical Research. In: Holmes MD, editor. Epilepsy Topics. InTech; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, Gale K, Kondratyev A. Early postnatal exposure of rats to lamotrigine, but not phenytoin, reduces seizure threshold in adulthood. Epilepsia. 2011;52:e20–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, Kalikhman D, Gale K. Delayed effect of craniotomy on experimental seizures in rats. PloS One. 2013;8:e81401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, Soper C, Lakhkar A, Gale K, Kondratyev A. Anticonvulsant effect of retigabine during postnatal development in rats. Epilepsy Res. 2012a;101:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, Sweeney CT, Kammerich AD, Lee BCW, Rubinson LH, Kayinamura YP, Gale K, Rubinson JF. Histocompatibility and in vivo signal throughput for PEDOT, PEDOP, P3MT, and polycarbazole electrodes. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012b;100:3455–3462. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, West EA, Murnen AT, Malkova L. Ventral pallidum mediates amygdala-evoked deficits in prepulse inhibition. Behav Neurosci. 2012c;126:290–300. doi: 10.1037/a0026898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman M, Zhan Q, McCafferty C, Lerner BA, Motelow JE, Meng J, Ma C, Buchanan GF, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Cardin JA, Blumenfeld H. Optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic brainstem neurons during focal limbic seizures: Effects on cortical physiology. Epilepsia. 2015;56:e198–202. doi: 10.1111/epi.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale K. Deep Brain Stimulation and Epilepsy. Tyler & Francis; London, UK: 2004. Basal ganglia circuitry as a substrate for seizure control; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gale K, Dubach M. Localization of area tempestas in the piriform cortex of the monkey. Presented at the Society for Neruoscience.1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gale K, Pazos A, Maggio R, Japikse K, Pritchard P. Blockade of GABA receptors in superior colliculus protects against focally evoked limbic motor seizures. Brain Res. 1993;603:279–283. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91248-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale K, Zhong P, Miller LP, Murray TF. Amino acid neurotransmitter interactions in “area tempestas”: an epileptogenic trigger zone in the deep prepiriform cortex. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;8:229–34. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-444-89710-7.50034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garant DS, Gale K. Substantia nigra-mediated anticonvulsant actions: role of nigral output pathways. Exp Neurol. 1987;97:143–159. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rill E, Skinner RD, Miyazato H, Homma Y. Pedunculopontine stimulation induces prolonged activation of pontine reticular neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;104:455–465. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Prakash R, Diester I, Goshen I, Thompson KR, Deisseroth K. Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell. 2010;141:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman N, Nikolic K, Grubb MS, Burrone J, Toumazou C, Degenaar P. High-frequency limit of neural stimulation with ChR2, in: 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society,EMBC. Presented at the 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society,EMBC; 2011. pp. 4167–4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen KM, Sun L, Polvivaara M, Brause M, Lehtimäki K, Haapasalo J, Möttönen T, Väyrynen K, Ogawa KH, Öhman J, Peltola J. Immediate effects of deep brain stimulation of anterior thalamic nuclei on executive functions and emotion-attention interaction in humans. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36:540–550. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2014.913554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AM, Huang L, Murphey DK, Garcia I, Arenkiel BR. Cell type-specific and time-dependent light exposure contribute to silencing in neurons expressing Channelrhodopsin-2. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.01481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AL, Forcelli PA, DesJardin JT, Decker AL, Teferra M, West EA, Malkova L, Gale K. Superior colliculus mediates cervical dystonia evoked by inhibition of the substantia nigra pars reticulata. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2012;32:13326–13332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2295-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadarola MJ, Gale K. Substantia nigra: site of anticonvulsant activity mediated by gamma-aminobutyric acid. Science. 1982;218:1237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.7146907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner S, Bringmann A. Nucleus basalis magnocellularis and pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus: control of the slow EEG waves in rats. Arch Ital Biol. 1996;134:153–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krook-Magnuson E, Armstrong C, Oijala M, Soltesz I. On-demand optogenetic control of spontaneous seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1376. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krook-Magnuson E, Szabo GG, Armstrong C, Oijala M, Soltesz I. Cerebellar Directed Optogenetic Intervention Inhibits Spontaneous Hippocampal Seizures in a Mouse Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. eneuro. 2014;1 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0005-14.2014. ENEURO.0005–14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krout KE, Loewy AD, Westby GW, Redgrave P. Superior colliculus projections to midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:198–216. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010305)431:2<198::aid-cne1065>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kügler S, Kilic E, Bähr M. Human synapsin 1 gene promoter confers highly neuron-specific long-term transgene expression from an adenoviral vector in the adult rat brain depending on the transduced area. Gene Ther. 2003;10:337–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]