Abstract

Background:

Nowadays self-medication is one of the most common public health issues in many countries, as well as in Iran. According to need to epidemiological information about self-medication, the aim of this study was to systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and cause of self-medication in community setting of Iran.

Methods:

Required data were collected searching following key words: medication, self-medication, over-the-counter, non-prescription, prevalence, epidemiology, etiology, occurrence and Iran in Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Magiran, SID and IranMedex (from 2000 to 2015). To estimate the overall self-medication prevalence, computer software CMA: 2 applied. In order to report the results, forest plot was employed.

Results:

Out of 1256 articles, 25 articles entered to study. The overall prevalence of self-medication based on the random effect model was estimated to be 53% (95% CI, lowest= 42%, highest=67%). The prevalence of self-medication in students was 67% (95% CI, lowest=55%, highest=81%), in the household 36% (95% CI, lowest=17%, highest= 77%) and in the elderly people 68% (95% CI, lowest=54%, highest=84%). The most important cause of self-medication was mild symptoms of disease. The most important group of disease in which patients self-medicated was respiratory diseases and the most important group of medication was analgesics.

Conclusion:

The results show a relatively higher prevalence of self-medication among the Iranian community setting as compared to other countries. Raising public awareness, culture building and control of physicians and pharmacies’ performance can have beneficial effects in reduce of prevalence of self-medication.

Keywords: Self-medication, Prevalence, Cause, Community setting, Iran

Introduction

Nowadays, the indiscriminate use of drugs, self-medication is among the greatest health, social and economic issues of different societies, includes Iran (1). Self-medication is a behavior in which the individual attempts to solve his/her health problem without professional opinion or help (2). The irrational and self-driven use of drugs can lead to various side effects (3, 4).

Among the most significant of these are microbial resistances, non-response to treatment, and toxications. Moreover, self-medication disrupts the drug market, wastes costs and increases per capita drug financing in the society (5–7).

The prevalence of self-medication varies from 12% to 90% in Iran (8–12). Moreover, each Iranian uses 339 drugs annually, a figure that exceeds the global standard. Analgesics, eye drops, and antibiotics hold the greatest share in self-medicated drugs (10, 13, 14). According to a report released by the Ministry of Health’s “Adverse Drug Reactions” (ADR) Center 10000 adverse drug reactions have been registered in the past 10 years, among which 30% belonged to injectable drugs (15).

The following factors affect the prevalence rate of self-medication among people: costly physician fees, transportation issues, insurance problems, easy access to drugs, feeling of well-being, not taking the disease seriously, previous prescription of the drug, unawareness, cultural and socio-economic issues, etc. (16–20).

Taking into account the high prevalence of self-medication in Iran and its adverse effects health officials and stakeholder organizations need to consider seriously reducing and preventing this phenomenon. To do this, they need accurate and valid information on the prevalence and etiology of self-treatment in the society. Hence, this study, which is a systematic review & meta-analysis, was conducted to provide health system managers, officials, and policy makers with useful and applicable data.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted in 2015, using the approach adopted in the book “A Systematic Review to Support Evidence-Based Medicine (21)”. Moreover, it was performed according to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) statement (22, 23).

The inclusion criteria for the study were cross-sectional community-based studies on the prevalence and causes of self-medication, studies conducted in Iran, articles published in Persian and English in Iran, articles published from 2000 to 2015.

Exclusion criteria included studies conducted in healthcare centers, conference presentations, case reports, interventional and qualitative studies.

Required data were collected by searching the following keywords: medication, self-medication, over-the-counter, non-prescription, prevalence, epidemiology, etiology, occurrence and Iran. The following databases were used: Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Magiran, Scientific Information Database (SID) and Iranmedex. Some of the relevant journals and websites were searched manually. The reference lists of the selected articles were also checked. In the final stage of the literature review, we searched the gray literature and consulted experts. There was no time limitation for our study search.

In the first phase of the review process, an extraction table was designed that included the following items: first author’s name, year of publication, city, sample and sample size, self-medication prevalence percent (in both males and females), Drug Group, determinant factors, cause of self-medication and type of request for the drug. The validity of the data extraction table was confirmed by experts. A pilot study (with5 articles) was conducted for further improvement of the extraction table. Two authors (M.M and N.M) who had sufficient experience and knowledge were responsible for independently extracting the data.

In the first phase of article selection, articles with non-relevant titles were excluded. In the second phase, the abstracts and full texts of articles were reviewed to include those articles that matched the inclusion criteria. Reference management (End-note X5-Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA 19130, USA) software was used to organize and assess the titles and abstracts, as well as to identify duplicate studies. Microsoft office Excel 2010 was used to draw graphs.

Two reviewers (M.M and N.M) evaluated the articles based on the “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) checklist (24–26). Cases in which a consensus had not been reached between these two reviewers were referred to a third author (A.A.S).

To estimate the overall self-medication prevalence, computer software CMA 2 (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis) (Englewood, NJ, USA) was used. Forest plot was employed to report the results. In the latter, the size of each square shows the sample size and the lines on each side of the square show the confidence interval. Self-medication prevalence was calculated based on the random effect model, with 95%confidence interval. Funnel plot was applied to evaluate the possibility of publication bias.

Results

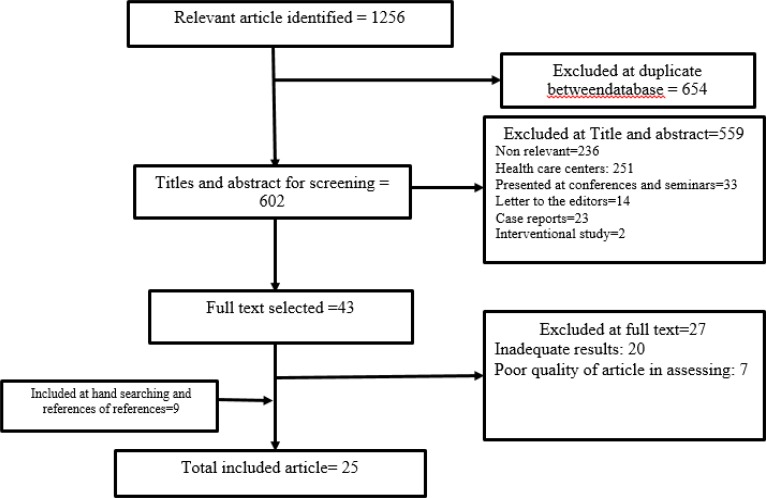

In this study, out of 1256 articles, finally 25 articles completely related to the study objects were included (1, 27–39, 9, 40–46, 12, 47) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

Bibliographical searches and inclusion process

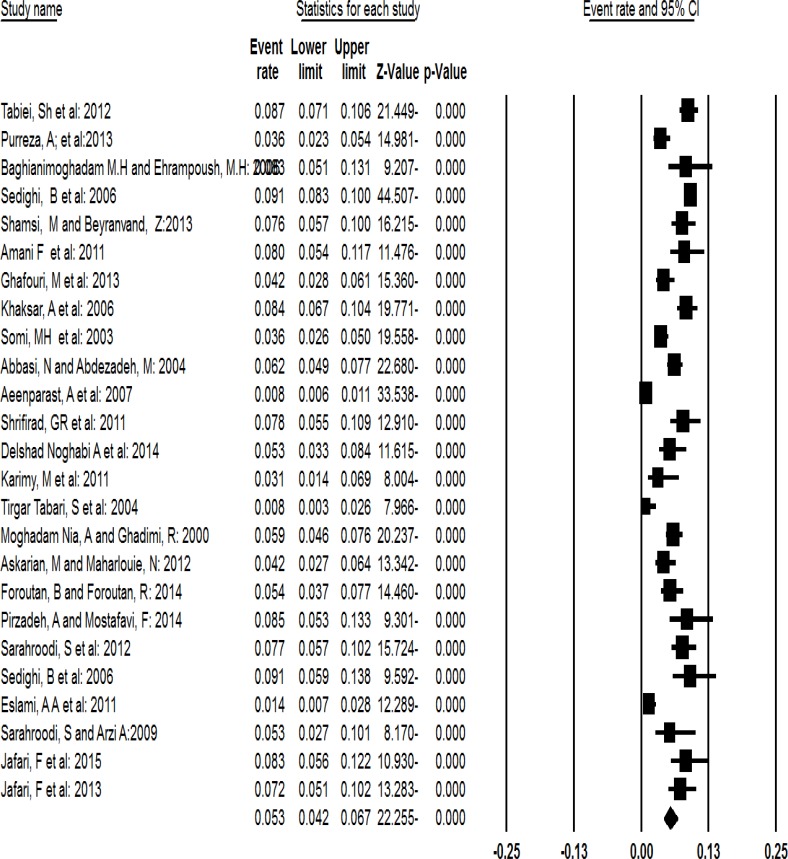

In 25 articles, which reviewed, 15222 individuals had gone under study. Most studies had been conducted in the city of Tehran. The highest and lowest prevalence were observed in Kerman Province among students, and among teachers in Babol, respectively. Among the most important determinant factors of self-medication were age, sex, education, financial status, place of residence, marital status and type of university (medical vs. non-medical). The overall prevalence of self-medication in community setting of Iran is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2:

The overall prevalence of self-medication in community setting of Iran

The overall prevalence of self-medication in community setting of Iran based on the random effect model was determined to be 53% (95% CI, lowest = 42%, highest = 67%). 95% CI for the prevalence was drawn for each study in the horizontal line format (Q = 363.8 df = 24, P < 0. 001 I2= 93.4).

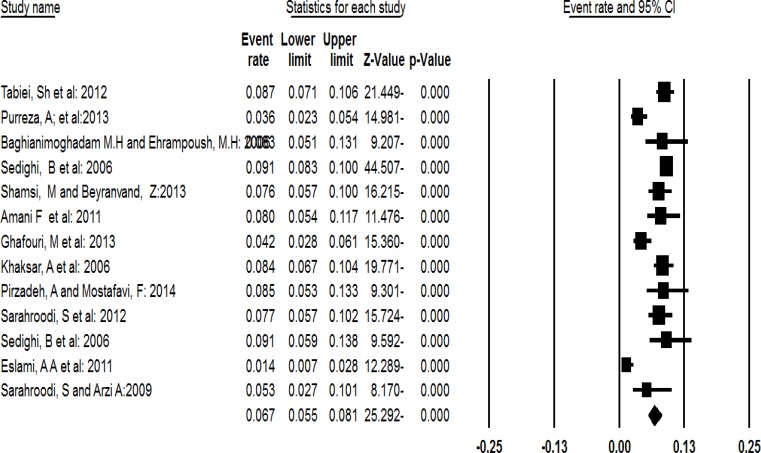

The prevalence of self-medication among students in community setting of Iran is shown in Fig. 3. The prevalence of self-medication among students in community setting of Iran based on the random effect model was determined to be 67% (95% CI, lowest = 55%, highest = 81%). 95% CI for the prevalence was drawn for each study in the horizontal line format (Q = 63.9 df = 12 P < 0. 001 I2= 81.2). The prevalence of self-medication among household in community setting of Iran is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3:

The prevalence of self-medication among students in community setting of Iran

Fig. 4:

The prevalence of self-medication among household in community setting of Iran

The prevalence of self-medication among household in community setting of Iran based on the random effect model was determined to be 36% (95% CI, lowest = 17%, highest = 77%). 95% CI for the prevalence was drawn for each study in the horizontal line format (Q = 150.8 df = 4 P < 0. 001 I2= 97.3).

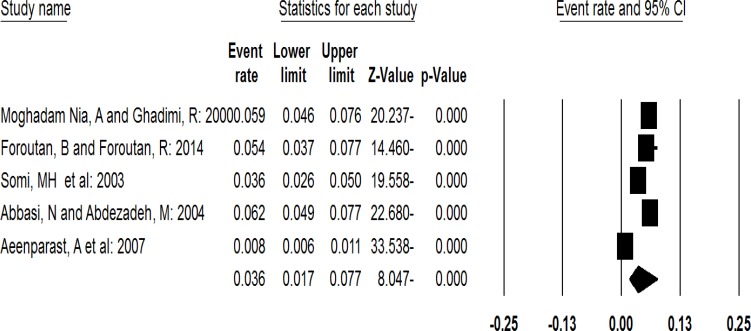

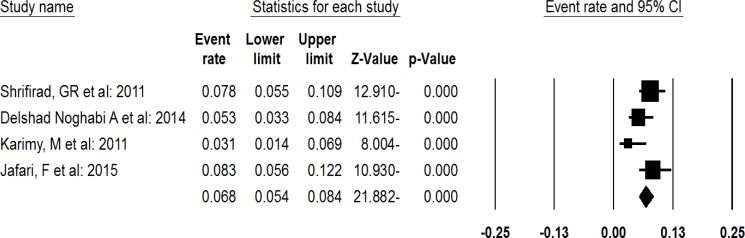

The prevalence of self-medication among elderly people in community setting of Iran is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5:

The prevalence of self-medication among elderly people in community setting of Iran

The prevalence of self-medication among elderly people in community setting of Iran based on the fixed effect model was determined to be 68% (95% CI, lowest = 54%, highest = 84%). 95% CI for the prevalence was drawn for each study in the horizontal line format (Q = 6.2 df = 3 P < 0. 09 I2= 52.2).

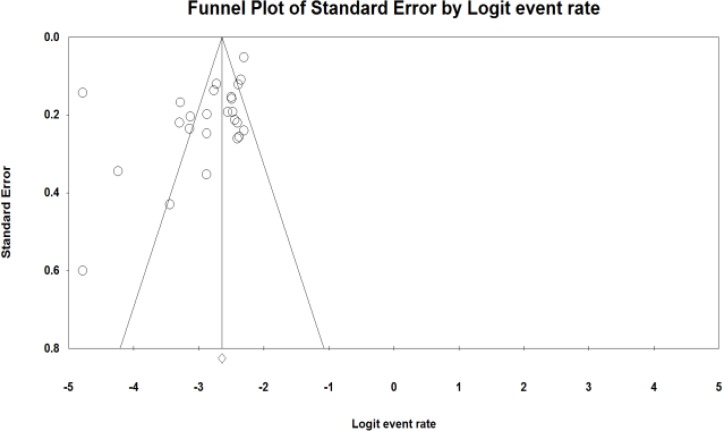

To evaluate the publication bias, funnel plot was applied (Fig. 6). Result of this funnel plot show there was possibility publication bias among studies.

Fig. 6:

Funnel plot of standard error by event rate

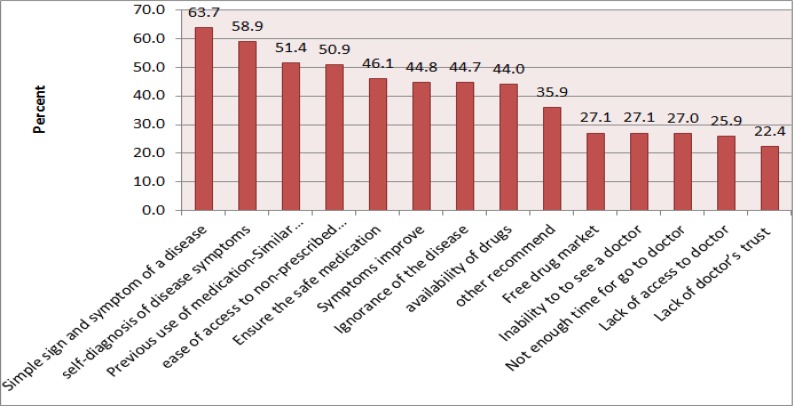

The most common causes of self-medication are shown in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 7, the most important self-medication determinant factors were: mild symptoms of disease, self-diagnosis of disease symptoms, previous use of medication, and ease of access to non-prescribed medication.

Fig. 7:

The most common causes of self-medication in community setting of Iran

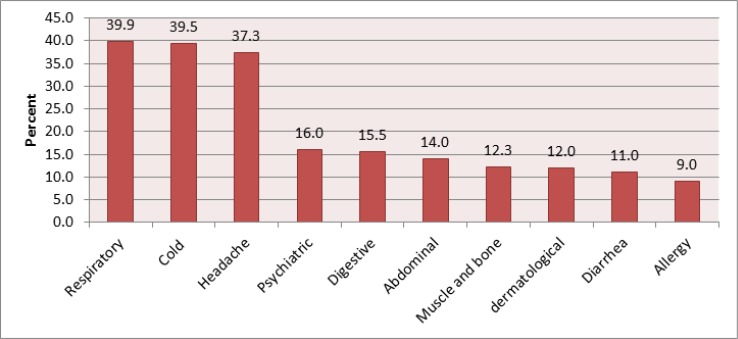

The most common groups of diseases, which patients’ self-medicated, are shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8:

The most common self-medicated groups of diseases in community setting of Iran

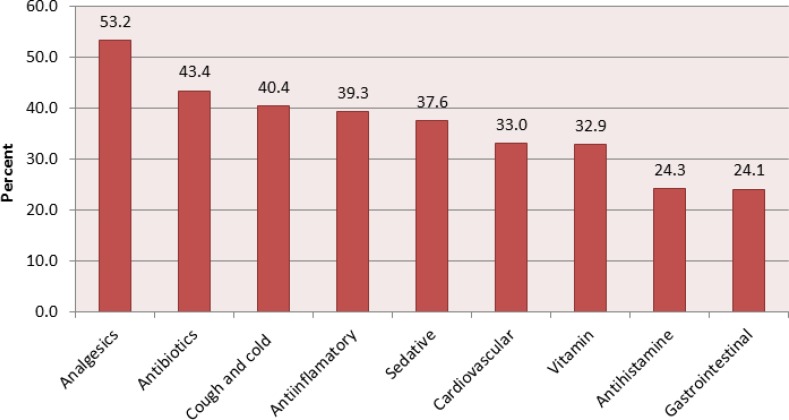

As seen in Fig. 8, the most important groups of diseases in which patients self-medicated were respiratory diseases, common cold and headache. The most common groups of medication, which patients self-medicated, are shown in Fig. 9. According to Fig. 9, the most important groups of medication that were self-prescribed were analgesics, antibiotics, and cold medications.

Fig. 9:

The most common self-medicated groups of medication in community setting of Iran

Discussion

The overall prevalence of self-medication in Iran was 53%. The most important determinant factors of self-medication were mild symptoms of disease, self-diagnosis of disease symptoms, previous use of medication, and ease of access to non-prescribed medication. The most important groups of diseases in which patients self-medicated were respiratory diseases, common cold and headache. The most important groups of medication that were self-prescribed were analgesics, antibiotics, and cold medications.

Based on our results, the overall prevalence of self-medication in Iran was 53%. This percentage exceeds that of other studies performed elsewhere: Brazil (2010) 29.9% (48), China (2011) 32.9% (49), Portugal (2014) 18.9% (50), Germany (2004) 13.8% (51), India (2014) 11.9% (4), and Nigeria (2011) 19.2% (52). Most other studies too have reported lower prevalence of self-medication than the one in Iran (53–57). The side effects of drugs are becoming more and more evident and people are getting more used to self-medication as the years pass by. Hence, medical universities and stake-holder organizations should try to reduce the rate of self-medication through proper planning, and prevent its harmful outcomes through the following measures: directing physicians toward the employment of non-medication treatment techniques, universal health insurance, reduction of treatment expenditures, creation of facilities for simple and inexpensive access to physicians, appropriate notification through mass media-Television & Radio-news agencies- publications and medical universities, raising public awareness of self-medication, limiting the sales of drugs without prescriptions, supervising pharmacies’ performance and other similar measures.

The prevalence of self-medication was higher among students (67%) than its mean public rate. This figure has been reported at a lower level in most studies conducted in other countries (58–62). However, some studies have reported the self-medication prevalences at rates higher than ours (2, 63–67). It seems that self-medication is more prevalent among students than it is among the public. Perhaps, their higher level of information–as compared to that of the public- can be one of the reasons behind this phenomenon. These individuals have access to greater information and self-medicate based on their incomplete data, an act that can be followed by detrimental effects. This phenomenon is probably higher among medical students than it is among students of other disciplines, reason being, the nature of their curricula and their high information in the fields of drugs and diseases. In any case, appropriate planning and intervention need to be carried out in this field; culture building among students and increasing their awareness on the effects of self-medication can prove beneficial.

Self-medication was also higher among the elderly (68%) than in the other community groups. Similar to the proportion observed in other groups in Iran, the prevalence of self-medication was higher among the Iranian elderly than among the elderly in other societies (68–70). The prevalence of self-medication among the elderly in the world is 38% (71). The high rate in Iran may be attributed to the low level of awareness among the elderly. A study showed an inverse relationship between self-medication and level of awareness among the elderly (37). Hence, health officials should raise awareness among this group. Upon entering the aging phase, treatment costs and medication use rise. Moreover, chronic diseases that predominantly affect the elderly cause pain & disability and reduce their quality of life, hence, raising their need for medication (72). In this respect, focus needs to be laid on the cognitive and physiologic changes that take place during aging and that pre-dispose the elderly toward medication use (73). Therefore, it is essential to teach the correct use of drugs to the elderly and advise abstinence of self-medication through models that identify and strengthen factors affecting behavior. One of the models that can prove effective for this goal is the “extended parallel process model’ (EPPM). Based on the EPPM, if individuals believe that they are highly at risk of a disease or exposed to a health risk, they will be more stimulated to confront that threat. In fact, fear of a threat causes individuals to adopt certain behaviors to confront that health threat. If the threat assessment is realized, and the efficacy of the solutions is assessed, the possibility of attitude change, behavioral intention and behavior will increase (74).

Mild symptoms of disease, self-diagnosis of disease symptoms, previous use of medication, and ease of access to non-prescribed medication were among the most important determinant factors of self-medication. These factors have been repeatedly reported in earlier studies (30, 53, 65, 75–82). Moreover, the most significant groups of diseases that are self-medicated i.e. respiratory diseases, common cold and headache, are similar to the findings of other studies too (4, 79, 83–96). Likewise, the most significantly self-medicated drugs in Iran were similar to those self-medicated elsewhere (76, 92, 95, 97–103). Prioritizing these factors while planning for self-medication reduction can yield greater results.

Limitations: One of the main limitations of this study was our lack of access to certain databases. Furthermore, certain details had not been reported in the published articles, so they could not be extracted. Laying greater focus on complete and detailed reporting in future research can resolve this problem.

Conclusion

The results of current study show a relatively higher prevalence of self-medication among the Iranian population in community setting as compared to other countries in the world. Moreover, it was relatively high in special groups (students, elderly and households). The most important reason behind self-medication was the appearance of mild symptoms of disease. The most significant group of diseases that were self-medicated was respiratory diseases, and the most important groups of drugs self-medicated were analgesics and antibiotics. The detrimental effects of self-medication from the health, social and economic perspectives warrant the need for appropriate planning and policy-making to reduce it. Raising public awareness, culture-building, control & supervision of physicians’ and pharmacies’ performance can have beneficial effects in this regard.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests and financial support for this study.

Reference

- 1. Abbasi N, Abduhzadeeh M. (2004). The Status of Self Medication in Ilam. Scientific Journal of Ilam University of Medical Sciences, 12 ( 42–43): 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klemenc-Ketis Z, Hladnik Z, Kersnik J. (2010). Self-medication among healthcare and nonhealthcare students at university of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Med Princ Pract, 19( 5): 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanchez J. (2014). Self-Medication Practices among a Sample of Latino Migrant Workers in South Florida. Front Public Health, 2: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Selvaraj K, Kumar SG, Ramalingam A. (2014). Prevalence of self-medication practices and its associated factors in Urban Puducherry, India. Perspect Clin Res, 5( 1): 32–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aoyama I, Koyama S, Hibino H. (2012). Self-medication behaviors among Japanese consumers: sex, age, and SES differences and caregivers’ attitudes toward their children’s health management. Asia Pac Fam Med, 11 (1): 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asseray N, Ballereau F, Trombert-Paviot B, Bouget J, Foucher N, Renaud B, et al. (2013). Frequency and severity of adverse drug reactions due to self-medication: a cross-sectional multicentre survey in emergency departments. Drug Saf, 36( 12): 1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heller T, Muller N, Kloos C, Wolf G, Muller UA. (2012). Self medication and use of dietary supplements in adult patients with endocrine and metabolic disorders. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes, 120( 9): 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jalilian F, Hazavehei S, Vahidinia A, Jalilian M, Moghimbeigi A. (2013). Prevalence and Related Factors for Choosing Self-Medication among Pharmacies Visitors Based on Health Belief Model in Hamadan Province, West of Iran. J Res Health Sci, 13( 1): 81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Purreza A, Khalafi A, Ghiasi A, Mojahed F, Nurmohammadi M. (2013). To Identify Self-medication Practice among Medical Students of Tehran University of Medical Science. Iran J Epidemiol, 8( 4): 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sedighi B, Ghaderi-Sohi S, Emami S. (2006). Evaluation of self-medication prevalence, diagnosis and prescription in migraine in Kerman, Iran. Neurosciences (Riyadh), 11( 2): 84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shamsi M, Bayati A. (2010). A survey of the Prevalence of Self-medication and the Factors Affecting it in Pregnant Mothers Referring to Health Centers in Arak city. JJUMS, 7( 3): 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tabibi S, Farajzadeh Z, Eizadpanah AM. (2012). Self-medication with drug amongst university students of Birjand. [Descriptive-Analytic]. Modern care(Scientific Quarterly of Birjand Nursing & Midwifery Faculty), 9( 4): 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahadian M. (2007). Self medication and drug abuse. J Drug Nedaye Mahya, 1( 3): 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ilhan MN, Durukan E, Ilhan SO, Aksakal FN, Ozkan S, Bumin MA. (2009). Self-medication with antibiotics: questionnaire survey among primary care center attendants. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 18( 12): 1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Food and Drug Department, Ministry of Health Pharmaceutical Statistics 2003 to 2008 [Online]. 2009; Available from: URL: http://hamahangi.behdasht.gov.ir.

- 16. Fruth B, Ikombe NB, Matshimba GK, Metzger S, Muganza DM, Mundry R, et al. (2014). New evidence for self-medication in bonobos: Manniophyton fulvum leaf- and stemstripswallowing fromLuiKotale, Salonga National Park, DR Congo. Am J Primatol, 76( 2): 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nguyen HV, Nguyen TH. (2013). Factors associated with self-medication among medicine sellers in urban Vietnam. Int J Health Plann Manage, 30( 3): 219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. White N, Mubarak S, Henderson JM, Pattinson J, Greenland J. (2013). An integrated assessment proforma and education package improves thromboembolic prophylaxis prescription in urological patients. J Clin Res Gov, 2( 1): 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silva K, Schrager SM, Kecojevic A, Lankenau SE. (2013). Factors associated with history of non-fatal overdose among young nonmedical users of prescription drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 128( 1–2): 104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sirey JA, Greenfield A, Weinberger MI, Bruce ML. (2013). Medication Beliefs and Self-Reported Adherence Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Clin Therap, 35( 2): 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. S Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine. Mazurek Melnyk B, editor. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. [Consensus Development Conference Guideline Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. PLoS Med, 6 (7): 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. [Consensus Development ConferenceGuideline]. BMJ, 21 (339). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Tabrizi JS, Azami-Aghdash S. (2014). Barriers to evidence-based medicine: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract, 20( 6): 793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. (2007). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med, 4 (10): e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Preven Med, 45( 4): 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aeenparast A, Maftoon F, Haghani H. (2007). Mizane Khoddarmani va Avamele Moaser Bar An dar Shahre Tehran. TebVaTazkieh, 16: 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amani F, Mohammadi S, Shaker A, Shahbazzadegan S. (2011). Study of Arbitrary Drug Use among Students in Universities of Ardabil City in 2010. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci 11( 3): 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Askarian M, Maharlouie N. (2012). Irrational Antibiotic Use among Secondary School Teachers and University Faculty Members in Shiraz, Iran. Int J Prev Med, 3: 839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baghianimoghadam M, Ehrampoush M. (2006). Evaluation of attitude and practice of students of Yazd University of Medical Sciences to self-medication. Tabib shargh, 2( 8): 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Delshad Noghabi A, Darabi F, BaloochiBeydokhti T, Shareinia H, Radmanesh R. (2014). Irrational use of Medicine Status in Elderly Population of Gonabad. Quarterly of the Horizon of Medical Sciences, 17( 5): 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eslami AA, Moazemi Goudarzi A, Najimi A, Sharifirad G. (2012). Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Students in Universities of Isfahan toward Self Medication. Health System Res, 7( 5): 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foroutan B, Foroutan R. (2014). Household storage of medicines and self-medication practices in south-east Islamic Republic of Iran. EMHJ, 20( 9): 547–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghafouri M, Yaghubi M, Lashkardoost H, Seyed Sharifi SH. (2013). The prevalence of self medication among students of Bojnurd universities and its related factors in 2013. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, 5: 1136. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jafari F, Davati A, Javanmard A, Behbahan SEB. (2013). Self-medication and its Related Factors in Health Educational Organization Staff. Biosci Biotech Res Asia, 10( 2): 775–780. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jafari F, Khatony A, Rahmani E. (2015). Prevalence of self-medication among the elderly inKermanshah-Iran. [Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t]. Glob J Health Sci, 7( 2): 360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karimy M, Heidarnia A, Ghofranipour F. (2011). Factors influencing self-medication among elderly urban centers in Zarandieh based on Health Belief Model. Arak Medical University Journal, 14( 5): 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khaksar A, Nader F, Musavi-zadeh K. (2006). A survey of the frequency of admini stering drugs without prescription among the students of medicine and engineering in 82–83. Journal of Jahrom Uiversity of Medical Sciences, 3( 3): 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pirzadeh A, Sharifirad G. (2012). Knowledge and practice among women about self-medication based on health belief model. J Gorgan Uni Med Sci, 13( 4): 76–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sarahroodi S, Maleki-Jamshid A, Sawalha A, Mikaili P, Safaeian L. (2012). Pattern of self-medication with analgesics among Iranian University students in central Iran. J Fam Community Med, 19: 125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sarahroodi S, Mikaili P. (2012). Self-medication with antibiotics:a global challenge of our generation. Pak J Biol Sci, 15( 14): 707–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sedighi B, Ghaderi-Sohi S, Emami S. (2006). Evaluation of self-medication prevalence, diagnosis and prescription in migraine in Kerman, Iran. Saudi Med J, 27( 3): 377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seyam S. (2003). Astudy on self-medication in Rasht city. Scientific Journal of llam Medical University, 10: 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shamsi M, Beyranvand Z. (2013). Knowledge, Attitude and practice of students of medical and none medical sciences about self-medication in Lorestan in 2013. Journal of Neyshabur University of MedicalSciences, 1 (1): 8. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sharifirad GR, Mohebbi S, Motalebi M, Abbasi MH, Rejati F, Tal A. (2011). The Prevalence and Effective Modifiable Factors of Self-Medication Based on the Health Belief Model among Elderly Adults in Gonabad in 2009. Journal of Health System Research, 7 (4): 411. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Somi M, Piri Z, Behshid M, Zaman Zadeh V, Abbas Alizadeh S. (2003). Self Medication by Residents of Northwestern Tabriz. J Med Sci University Tabriz, 59( 1): 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tirgar TS, Hajian K, Naderi A. (2004). Self-Management In Skin Disease Among Babolian Teachers (Educational Year Of 2000–2001). Journal of Babol University of Medical Sciences, 6( 2): 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schmid B, Bernal R, Silva NN. (2010). Self-medication in low-income adults in Southeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica, 44( 6): 1039–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. You JH, Wong FY, Chan FW, Wong EL, Yeoh EK. (2011). Public perception on the role of community pharmacists in self-medication and self-care in Hong Kong. BMC Clin Pharmacol, 11: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ramalhinho I, Cordeiro C, Cavaco A, Cabrita J. (2014). Assessing determinants of self-medication with antibiotics among Portuguese people in the Algarve Region. Int J Clin Pharm, 36( 5): 1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Beitz R, Doren M, Knopf H, Melchert HU. (2004). [Self-medication with over-the-counter(OTC) preparations in Germany]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz, 47( 11): 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bello FA, Morhason-Bello IO, Olayemi O, Adekunle AO. (2011). Patterns and predictors of self-medication amongst antenatal clients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Niger Med J, 52( 3): 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Figueiras A, Caamano F, Gestal-Otero JJ. (2000). Sociodemographic factors related to self-medication in Spain. Eur J Epidemiol, 16( 1): 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, Deschepper R, Lundborg CS, Monnet DLet al. (2008). Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and the healthcare system. J Antimicrob Chemother, 61( 5): 1172–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grigoryan L, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Burgerhof JG, Mechtler R, Deschepper R, Tambic-Andrasevic A, et al. (2006). Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis, 12( 3): 452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Grigoryan L, Monnet DL, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Bonten MJ, Lundborg S, Verheij TJ. (2010). Self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: a case for action. Curr Drug Saf, 5( 4): 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lal V, Goswami A, Anand K. (2007). Self-medication among residents of urban resettlement colony, New Delhi. Indian J Public Health, 51( 4): 249–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Buke C, Limoncu M, Ernevtcan S, Ciceklioghlu M, Tuncel M, Kose T, et al. (2005). Irrational use of antibiotics among university students. J Infect, 51: 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hussain A, Khanum A. (2008). Self medication among universitystudents of Islamabad, Pakistan- a preliminary study. Southern Med Review, 1( 1): 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pan H, Cui B, Zhang D, Farrar J, Law F, Ba-Thein W. (2012). Prior knowledge, older age, and higher allowance are risk factors for self-medication with antibiotics among university students in southern China. PLoS One, 7(7): e41 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sapkota AR, Coker ME, Rosenberg Goldstein RE, Atkinson NL, Sweet SJ, Sopeju PO, et al. (2010). Self-medication with antibiotics for the treatment of menstrual symptoms in Southwest Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 10: 610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shankar PR, Partha P, Shenoy N. (2002). Self-medication and non-doctor prescription practices in Pokhara valley, Western Nepal: a questionnaire-based study. BMC Fam Pract, 3: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Abay SM, Amelo W. (2010). Assessment of self-medication practices among medical, pharmacy, and health science students in gondar university, ethiopia. J Young Pharm, 2( 3): 306–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McCabe SE. (2008). Misperceptions of non-medical prescription drug use: A web survey of college students. Addictive Behaviors, 33( 5): 713–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sawalha AF. (2008). A descriptive study of self-medication practices among Palestinian medical and nonmedical university students. Res Social Adm Pharm, 4( 2): 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tse MH, Chung JT, Munro JG. (1989). Self-medication among secondary school pupilsin Hong Kong: a descriptive study. Fam Pract, 6( 4): 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zafar SN, Syed R, Waqar S, Zubairi AJ, Vaqar T, Shaikh M, et al. (2008). Self-medication amongst university students of Karachi: prevalence, knowledge and attitudes. J Pak Med Assoc, 58( 4): 214–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Balbuena FR, Aranda AB, Figueras A. (2009). Self-medication in older urban mexicans : an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging, 26( 1): 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bortolon PC, de Medeiros EF, Naves JO, Karnikowski MG, Nobrega Ode T. (2008). [Analysis of the self-medication pattern among Brazilian elderly women]. Cien Saude Colet, 13( 4): 1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Goh LY, Vitry AI, Semple SJ, Esterman A, Luszcz MA. (2009). Self-medication with over-the-counter drugs and complementary medications in South Australia’s elderly population. BMC Complement Altern Med, 9: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jerez-Roig J, Medeiros LF, Silva VA, Bezerra CL, Cavalcante LA, Piuvezam G, et al. (2014). Prevalence of self-medication and associated factors in an elderly population: a systematic review. Drugs Aging, 31( 12): 883–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Amoako EP, Richardson-Campbell L, Kennedy-Malone L. (2003). Self-medication with over-the-counter drugs among elderly adults. J Gerontol Nurs, 29( 8): 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vacas Rodilla E, Castella Daga I, Sanchez Giralt M, Pujol Algue A, Pallares Comalada MC, Balague Corbera M. (2009). [Self-medication and the elderly. The reality of the home medicine cabinet]. Aten Primaria, 41( 5): 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gharlipour Gharghani Z, Hazavehei M, Sharifi MH, Nazari M. (2010). Study of cigarette smoking status using extended parallel process model (EPPM) among secondary school male students in Shiraz city. Health Sci J, 2( 3): 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Abasiubong F, Bassey EA, Udobang JA, Akinbami OS, Udoh SB, Idung AU. (2012). Self-Medication: potential risks and hazards among pregnant women in Uyo, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J, 13: 15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Al-Ramahi R. (2013). Patterns and attitudes of self-medication practices and possible role of community pharmacists in Palestine. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther, 51( 7): 562–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Horton S, Stewart A. (2012). Reasons for self-medication and perceptions of risk among Mexican migrant farm workers. J Immigr Minor Health, 14( 4): 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jalilian F, Hazavehei SM, Vahidinia AA, Jalilian M, Moghimbeigi A. (2012). Prevalence and Related Factors for Choosing Self-Medication among Pharmacies Visitors Based on Health Belief Model in Hamadan Province, West of Iran. J Res Health Sci, 13( 1): 81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jassim AM. (2010). In-home Drug Storage and Self-medication with Antimicrobial Drugs in Basrah, Iraq. Oman Med J, 25( 2): 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Omolase CO, Adeleke OE, Afolabi AO, Afolabi OT. (2007). Self medication amongst general outpatients in a nigerian community hospital. Ann Ib Postgrad Med, 5( 2): 64–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sweileh WM, Ihbesheh MS, Jarar IS, Taha ASA, Sawalha AF, Zyoud SeH, et al. (2011). Self-reported medication adherence and treatment satisfaction in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior, 21( 3): 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yousef AM, Al-Bakri AG, Bustanji Y, Wazaify M. (2008). Self-medication patterns in Amman, Jordan. Pharm World Sci, 30( 1): 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ahmad A, Patel I, Mohanta G, Balkrishnan R. (2014). Evaluation of self medication practices in rural area of town sahaswan at northern India. Ann Med Health Sci Res, 4( Suppl 2): S73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Du Y, Knopf H. (2009). Self-medication among children and adolescents in Germany: results of the National Health Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Br J Clin Pharmacol, 68( 4): 599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Eticha T, Mesfin K. (2014). Self-medication practices in Mekelle, Ethiopia. PLoS One, 9 (5): e97464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Markovic-Pekovic V, Grubisa N. (2012). Self-medication with antibiotics in the Republic of Srpska community pharmacies: pharmacy staff behavior. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 21( 10): 1130–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mehuys E, Paemeleire K, Van Hees T, Christiaens T, Van Bortel L, Van Tongelen I, et al. (2012). [Self-medication of regular headache: a community pharmacy-based survey in Belgium]. J Pharm Belg, (2): 4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mehuys E, Paemeleire K, Van Hees T, Christiaens T, Van Bortel LM, Van Tongelen I, et al. (2012). Self-medication of regular headache: a community pharmacy-based survey. Eur J Neurol, 19( 8): 1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mohanna M. (2010). Self-medication with Antibiotic in Children in Sana’a City, Yemen. Oman Med J, 25( 1): 41–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Muras M, Krajewski J, Nocun M, Godycki-Cwirko M. (2013). A survey of patient behaviours and beliefs regarding antibiotic self-medication for respiratory tract infections in Poland. Arch Med Sci, 9( 5): 854–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ocan M, Bwanga F, Bbosa GS, Bagenda D, Waako P, Ogwal-Okeng J, et al. (2014). Patterns and predictors of self-medication in northern Uganda. PLoS One, 9 (3): e92323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sarahroodi S, Maleki-Jamshid A, Sawalha AF, Mikaili P, Safaeian L. (2012). Pattern of self-medication with analgesics among Iranian University students in central Iran. J Family Community Med, 19( 2): 125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Schrand JR. (2010). Does insular stroke disrupt the self-medication effects of nicotine? Med Hypotheses, 75( 3): 302–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Scicluna EA, Borg MA, Gür D, Rasslan O, Taher I, Redjeb SBet al. (2009). Self-medication with antibiotics in the ambulatory care setting within the Euro-Mediterranean region; results from the ARMed project. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 2( 4): 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shehnaz SI, Khan N, Sreedharan J, Issa KJ, Arifulla M. (2013). Self-medication and related health complaints among expatriate high school students in the United Arab Emirates. Pharm Pract (Granada), 11( 4): 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Vacas Rodilla E, Castellà Dagà I, Sánchez Giralt M, Pujol Algué A, Pallarés Comalada MC, Balagué Corbera M. (2009). Automedicación y ancianos. La realidad de un botiquín casero. Atención Primaria, 41( 5): 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Benotsch EG, Zimmerman R, Cathers L, McNulty S, Pierce J, Heck T, et al. (2013). Non-medical use of prescription drugs, polysubstance use, and mental health in transgender adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132( 1–2): 391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bertoldi AD, Camargo AL, Silveira MP, Menezes AM, Assuncao MC, Goncalves H, et al. (2014). Self-medication among adolescents aged 18 years: the 1004 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. J Adolesc Health, 55( 2): 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Giese A, Ornek A, Kurucay M, Kilic L, Sendur SN, Munker A, et al. (2013). [Self-medication to treat pain in attacks of familial Mediterranean fever: aiming to find a new approach to pain management]. Schmerz, 27( 6): 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lawan UM, Abubakar IS, Jibo AM, Rufai A. (2013). Pattern, awareness and perceptions of health hazards associated with self medication among adult residents of kano metropolis, northwestern Nigeria. Indian J Community Med, 38( 3): 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Morgenstern EC, Heintze K. (2013). [Effectiveness of analgesic combinations in the self-medication]. MMW Fortschr Med, 155( 9): 49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ndol FM, Bompeka FL, Dramaix-Wilmet M, Meert P, Malengreau M, Mangani NN, et al. (2013). [Self-medication among patients admitted to the emergency department of Kinshasa University Hospital]. Sante Publique, 25( 2): 233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Pineles LL, Parente R. (2013). Using the theory of planned behavior to predict self-medication with over-the-counter analgesics. J Health Psychol, 18( 12): 1540–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]