Abstract

BACKGROUND

Understanding residential mobility in early childhood is important for contextualizing influences on child health and well-being.

OBJECTIVE

This study describes individual, household, and neighborhood characteristics associated with residential mobility for children aged 0–5.

METHODS

We examined longitudinal data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), a nationally representative sample of children born in 2001. Frequencies describe the prevalence of characteristics for four waves of data and adjusted Wald tests compared means.

RESULTS

Moving was common for these families with young children, as nearly three-quarters of children moved at least once. Movers transitioned to neighborhoods with residents of higher socioeconomic status but experienced no improved household socioeconomic position relative to non-movers.

CONCLUSION

Both the high prevalence and unique implications of early childhood residential mobility suggest the need for further research.

Keywords: Early childhood, residential mobility, SES, race, ECLS-B

1. Introduction

Research shows that residential mobility shapes child well-being. Children who stay in the same home have better behavioral and emotional health and educational achievement than their more mobile counterparts (Jelleyman & Spencer 2008; Leventhal & Newman 2010; Ziol-Guest & McKenna 2014). The mechanisms behind these associations include changes in social relationships such as friendship networks (South and Haynie 2004) and disruptions in institutional supports such as health insurance or medical facilities (Busacker and Kasehagen 2012). Complicating causal interpretation of observed associations are the many confounding factors that influence both mobility and well-being. For example, Dong and colleagues (2005) reported that adverse childhood experiences, such as childhood abuse, are associated with residential mobility and explain the effect of frequent moving on health risks. Controlling for selection is therefore important for determining the effects of residential mobility, since mobile and nonmobile families differ in many ways (Gasper, DeLuca, & Estacion 2010). This is particularly important because some studies find that mobility exerts an independent influence on child well-being (Pribesh & Downey 1999) which cannot be examined without properly controlling for selection bias.

Further, moving does not necessarily have negative consequences, as many families move for positive reasons, such as a new or better job or to have a child attend a chosen school. Prior research has found differential effects of mobility depending on neighborhood context, child’s age/developmental period, and financial resources (Anderson, Leventhal, & Dupere 2014; Pettit 2004). Giving birth to a young child may precipitate a particular type of move, since this life course change can spur relocation efforts (Mulder & Hooimeijer 1999; Rabe & Taylor 2010). It is therefore important to examine mobility among young children separately from other groups.

Researchers usually operationalize mobility based on a short window of time prior to the interview, excluding the influence of moves earlier in life. Yet, early development shapes later development (Willson, Shuey, & Elder 2007). Further, social influences show a cumulative process over time. Evidence points to the importance of childhood circumstances for adult health outcomes (Gruenewald et al. 2012; Haas 2007; Hayward & Gorman 2004). Examining mobility at the youngest ages is therefore crucial for understanding both the effects of mobility on child health and well-being and how residential mobility is influenced by a variety of individual, family, and neighborhood constraints.

To understand young children’s mobility in the United States, it is critical to determine who is moving in early childhood and identify the circumstances of movers and non-movers. To this end, we describe levels of mobility (defined by number of moves) across ages 0–5 and the family and neighborhood characteristics that are associated with these different levels. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine early childhood residential mobility over time using a nationally representative sample. By describing mobility patterns across dynamic household and neighborhood characteristics, we provide context for future studies that seek to examine the effects of child residential mobility and health.

2. Methods

We used all waves of data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), which followed a nationally representative cohort of U.S. children born in 2001 at approximately 9 months, 2 years, 4 years, 5 years, and 6 years of age. Since the last wave of data only included a subsample of children who had not yet started kindergarten in the fourth wave, household and neighborhood information at kindergarten start was taken from either the fourth or fifth wave. The ECLS-B dataset is uniquely suited for this study because it covers early childhood and its longitudinal design does not exclude movers (Snow et al. 2009).

Approximately 6,350 children had a valid kindergarten sampling weight and the biological mother as the respondent for all waves. Of these, 6,250 had complete data on moving. Some parents reported that they did not move, but the data showed they changed ZIP codes. Because we do not know the source of the error, we dropped these children (N≈150). The resulting sample size is 6,100 (96%). Some indicators had missing data, resulting in a sample reduction ranging from 0–3% for each measure. All numbers reported here were rounded to the nearest 50 per NCES security requirements. Adjusted Wald tests compared means across mover statuses. We adjusted for complex sample design using jackknife replication weights.

Our focal variable was residential mobility across the study period. At Waves 2, 3, 4, and 5, parents were asked if they moved since the last interview and, if they moved in waves 2, 3, or 4, how many times they moved. We assumed one move for those moving in the year between Waves 4 and 5. Respondents reporting at Wave 2 they had been at their residence since before Wave 1, but not since the child’s birth, were assigned one move between birth and Wave 1. We summed together responses across the study period, which likely undercounts moves but captures birth to kindergarten start. We categorized the number of moves as 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more. The maximum number of moves per child was 25; supplemental analysis revealed that top-coding at 4 rather than 3 moves produced similar results.

Individual and household socio-demographic measures were derived from constructed ECLS-B variables and parent interviews. Individual measures included sex, race, and age (in months) of the child at each wave. We also included the following household indicators at each wave: mother’s educational attainment (in years), mother’s marital status, and income-to-needs ratio (the ratio of the household income to the year and household size-specific poverty threshold). Mother’s age at birth of the focal child and her first child were also examined.

For residential location measures, we used region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), urbanicity (urbanized area [population ≥ 50,000], urbanized cluster [population ≥ 2500 and <50,000], or rural [population < 2500]), ZIP code characteristics, and parent-reported neighborhood safety. ZIP code of residence was used as a proxy for neighborhood (a limitation of the ECLS-B dataset, as this was the only geographic identifier collected), and characteristics were extracted from the 2000 Census SF3. ZIP code characteristics included the percent of the population living below poverty, the percent with a college degree, the median household income, and the percentages White, Black, and Hispanic. Townsend and Carstairs indices were also developed from Census data and capture material deprivation in the neighborhood (Carstairs & Morris 1991; Townsend et al. 1998). ECLS-B offered one survey item of parent perceptions of the neighborhood that is consistent across waves. Parents were asked to report whether they believed their neighborhood is safe from crime, and responses were dichotomized into those reporting very safe and those reporting fairly safe, fairly unsafe, and very unsafe. All parents answered this question in Wave 2, but only parents who reported having moved since the last wave were asked this question in Waves 3 and K.

3. Results

Table 1 presents individual and household characteristics across the study period by mover status. Most children (73%) moved at least once between birth and the start of kindergarten, and 26% moved three or more times during the entire study period (Waves 1 through K). Movers, and particularly those moving three or more times, were disproportionately Black or Hispanic and low-income. Mother’s ages at first birth and birth of the sample child showed a linear gradient, such that older mothers moved less often. Looking at differences from infancy to the start of kindergarten, mothers of movers increased their educational attainment and income-to-needs ratios, and a greater proportion were married at the later time point. However, non-movers also improved on these indicators, resulting in a mostly constant disadvantage for movers over time. For example, the income-to-needs ratios of the never movers increased from 3.6 in Wave 1 to 4.0 in Wave K and those moving three or more times increased from 1.9 to 2.2. Even though the levels of income-to-needs differed at each of the waves, the change over time did not significantly differ, signifying that both groups made gains at about the same rate.

Table 1.

Individual and household characteristics, across mover categories

| All | Never moved |

Moved once | Moved twice | Moved 3+ | Adj. Wald Test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 27.2% | 28.7% | 18.2% | 26.0% | ||

| Male | 50.8% | 49.2% | 50.2% | 53.4% | 51.4% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 53.5% | 63.2% | 56.2% | 48.7% | 43.8% | *** |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.8% | 8.5% | 12.3% | 17.5% | 18.2% | *** |

| Hispanic | 25.6% | 22.2% | 23.3% | 26.6% | 31.0% | ** |

| A/PI | 2.7% | 3.0% | 3.3% | 3.0% | 1.6% | *** |

| AI/AN | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.8% | *** |

| Multiracial | 4.0% | 2.8% | 4.5% | 3.8% | 4.7% | |

| Age in months (W1) | 10.5 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.7 | *** |

| Age in months (W2) | 24.4 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 24.4 | 24.6 | *** |

| Age in months (W3 | 52.3 | 51.7 | 52.0 | 52.8 | 53.0 | *** |

| Age in months (WK) | 68.1 | 68.0 | 68.0 | 67.9 | 68.7 | ** |

| Mom's education in years (W1) | 13.3 | 13.9 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 12.5 | *** |

| Mom's education in years (W2) | 13.3 | 13.9 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 12.5 | *** |

| Mom's education in years (W3) | 13.5 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 13.3 | 12.7 | *** |

| Mom's education in years (WK) | 13.5 | 14.0 | 13.8 | 13.4 | 12.8 | *** |

| W1 to WK mom education change | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Income-to-needs (W1) | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.9 | *** |

| Income-to-needs (W2) | 3.0 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.0 | *** |

| Income-to-needs (W3) | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | *** |

| Income-to-needs (WK) | 3.3 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 2.2 | *** |

| W1 to WK income-to-needs change | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| Mom is married (W1) | 68.5% | 85.1% | 73.7% | 61.5% | 50.2% | *** |

| Mom is married (W2) | 69.5% | 85.1% | 73.6% | 63.5% | 52.7% | *** |

| Mom is married (W3) | 70.2% | 85.5% | 75.2% | 65.5% | 51.9% | *** |

| Mom is married (WK) | 70.1% | 85.3% | 74.2% | 65.7% | 52.5% | *** |

| W1 to WK marital status change | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 2.2 | |

| Mom age at birth | 27.5 | 30.9 | 28.3 | 26.1 | 24.1 | *** |

| Mom age at first birth | 24.0 | 26.3 | 24.9 | 23.1 | 21.4 | *** |

Source: ECLS-B (2001–2007).

Notes: Adjusted for complex sampling design. N ≈ 6100.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

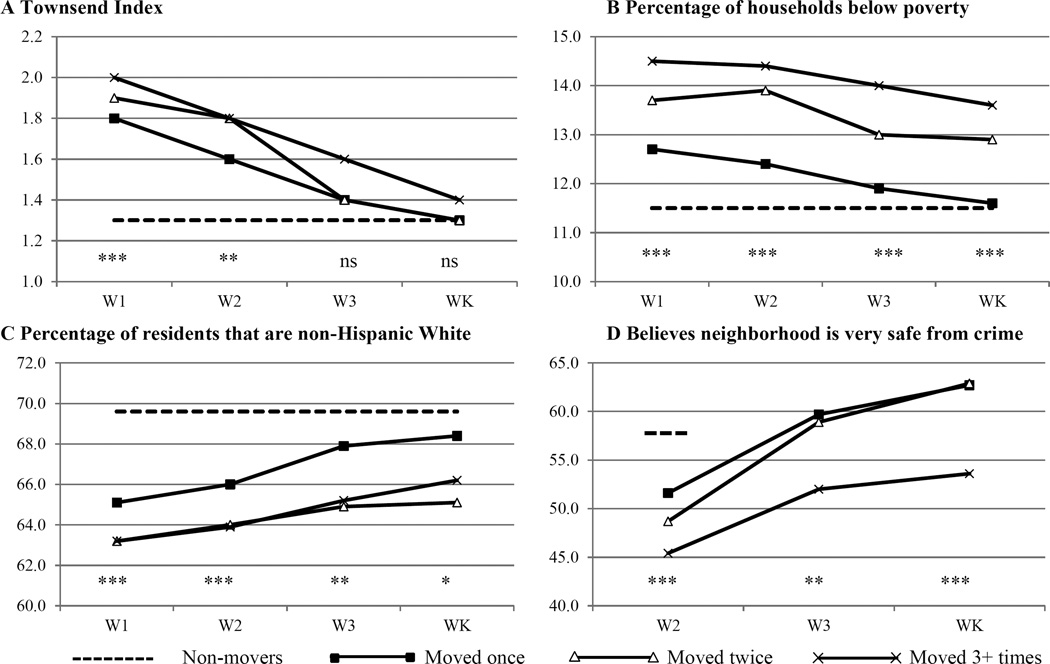

Table 2 displays neighborhood and geographic characteristics over time. In contrast to household factors, neighborhood characteristics generally improved among movers relative to non-movers. The Townsend Index, a measure of relative deprivation, shows a distinct downward trend among all movers (lower scores indicate less deprivation). Although there was a stark contrast in this measure at Wave 1 for non-movers compared to movers, there was no significant difference at Wave K across mover status, and the change in the Townsend Index from Wave 1 to Wave K differed significantly across mover status. Figure 1, Panel A visually presents the convergence over time for the Townsend index. Similar trends were observed for the other ZIP code characteristics, with differing magnitudes. Figure 1, Panel B illustrates the improvements in percentage of residents in poverty for movers, with those moving only once displaying similar values at Wave K compared to non-movers.

Table 2.

Residential location characteristics, across mover categories

| All | Never moved |

Moved once |

Moved twice |

Moved 3+ |

Wald Test |

All | Never moved |

Moved once |

Moved twice |

Moved 3+ |

Wald Test |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Townsend Index | Northeast | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 | *** | W1 | 17.4 | 21.5 | 18.5 | 16.3 | 12.5 | |

| W2 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | ** | W2 | 17.3 | 21.5 | 18.3 | 16.4 | 12.4 | * |

| W3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | W3 | 16.9 | 21.5 | 18.0 | 15.5 | 12.0 | * | |

| WK | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | WK | 16.8 | 21.5 | 18.1 | 15.0 | 11.6 | * | |

| W1 to WK change | −0.4 | 0.0 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.5 | *** | W1 to WK | −0.6 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −1.4 | −0.9 | * |

| Carstairs Index | Midwest | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 | *** | W1 | 22.1 | 24.5 | 20.2 | 21.1 | 22.5 | |

| W2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | *** | W2 | 22.0 | 24.5 | 20.4 | 21.0 | 21.9 | |

| W3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | *** | W3 | 21.7 | 24.5 | 20.0 | 20.9 | 21.1 | |

| WK | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | ** | WK | 21.7 | 24.5 | 20.6 | 20.3 | 20.9 | |

| W1 to WK change | −0.3 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.4 | *** | W1 to WK | −0.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | −0.9 | −1.6 | * |

| Living below poverty | South | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 13.0 | 11.5 | 12.7 | 13.7 | 14.5 | *** | W1 | 36.1 | 31.5 | 36.3 | 38.0 | 39.2 | * |

| W2 | 12.9 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 13.9 | 14.4 | *** | W2 | 36.3 | 31.5 | 36.4 | 38.6 | 39.6 | * |

| W3 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 13.0 | 14.0 | *** | W3 | 37.2 | 31.5 | 37.4 | 39.6 | 41.4 | ** |

| WK | 12.3 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 12.9 | 13.6 | *** | WK | 37.3 | 31.5 | 36.8 | 40.7 | 41.7 | ** |

| W1 to WK change | −0.8 | 0.0 | −1.2 | −0.9 | −1.0 | *** | W1 to WK | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | ** |

| Median Household Income (in thousands) | West | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 44.5 | 47.7 | 46.2 | 43.1 | 40.3 | *** | W1 | 24.4 | 22.5 | 25.0 | 24.5 | 25.8 | |

| W2 | 44.7 | 47.7 | 46.6 | 42.8 | 40.6 | *** | W2 | 24.4 | 22.5 | 24.9 | 24.0 | 26.1 | |

| W3 | 45.5 | 47.7 | 47.1 | 44.6 | 41.7 | *** | W3 | 24.2 | 22.5 | 24.6 | 24.0 | 25.5 | |

| WK | 45.7 | 47.7 | 47.6 | 44.7 | 42.1 | *** | WK | 24.2 | 22.5 | 24.5 | 24.0 | 25.9 | |

| W1 to WK change | 1.3 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | *** | W1 to WK | −0.2 | 0.0 | −0.4 | −0.5 | 0.0 | |

| % with College Education | Urban area | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 23.5 | 25.0 | 25.2 | 22.6 | 20.7 | *** | W1 | 74.8 | 73.2 | 78.0 | 75.0 | 72.7 | * |

| W2 | 23.4 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 22.1 | 21.0 | *** | W2 | 74.2 | 73.0 | 77.4 | 73.8 | 72.0 | * |

| W3 | 23.4 | 25.0 | 24.7 | 22 2 | 21.1 | *** | W3 | 72.5 | 73.0 | 74.9 | 71.0 | 70.2 | |

| WK | 23.5 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 22.5 | 20.8 | *** | WK | 71.9 | 73.0 | 74.9 | 70.7 | 68.1 | |

| W1 to WK change | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | W1 to WK | −2.8 | −0.3 | −3.1 | −4.0 | −4.1 | ** | |

| % White | Urban cluster | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 65.5 | 69.6 | 65.1 | 63.2 | 63.2 | *** | W1 | 10.9 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 11.5 | 14.0 | ** |

| W2 | 66.1 | 69.6 | 66.0 | 64.0 | 63.9 | ** | W2 | 11.5 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 11.1 | 13.2 | ** |

| W3 | 67.1 | 69.6 | 67.9 | 64.9 | 65.2 | ** | W3 | 11.6 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 14.0 | |

| WK | 67.5 | 69.6 | 68.4 | 65.1 | 66.2 | * | WK | 11.6 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 14.8 | * |

| W1 to WK change | 2.2 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 3.0 | *** | W1 to WK | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| % Black | Rural | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 12.7 | 9.8 | 12.6 | 14.5 | 14.7 | *** | W1 | 14.1 | 16.4 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 13.3 | |

| W2 | 12.6 | 9.8 | 12 2 | 14.6 | 14.7 | *** | W2 | 15.0 | 16.5 | 13.7 | 15.1 | 14.8 | |

| W3 | 12.3 | 9.8 | 11.6 | 14.5 | 14.1 | *** | W3 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 17.3 | 15.8 | |

| WK | 11.9 | 9.8 | 11.6 | 14.1 | 12.9 | ** | WK | 16.4 | 16.6 | 15.2 | 17.5 | 17.1 | |

| W1 to WK change | −0.9 | 0.0 | −1.2 | −0.5 | −1.9 | ** | W1 to WK | 2.4 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 3.8 | ** |

| % Hispanic | Believes neighborhood is very safe from crime | ||||||||||||

| W1 | 15.4 | 14.3 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 16.0 | ||||||||

| W2 | 15.0 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 15.5 | W2 | 51.2 | 57.8 | 51.6 | 48.7 | 45.4 | *** | |

| W3 | 14.5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 14.8 | 14.8 | W3 | 57.1 | 59.7 | 58.9 | 52.0 | ** | ||

| WK | 14.5 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 15.0 | 15.2 | WK | 59.1 | 62.7 | 62.9 | 53.6 | *** | ||

| W1 to WK | −0.9 | 0.0 | −1.8 | −1.0 | −0.7 | *** | |||||||

Source: ECLS-B (2001–2007).

Notes: Adjusted for complex sampling design. N≈6100.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 1.

Means of neighborhood characteristics over time, by mover status

Source: ECLS-B (2001 – 2007).

Notes: Adjusted for complex sampling design. N ≈ 6100.

+p < .10 * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

While neighborhood racial composition is a complex issue, many individuals, especially white Americans with children under age 18, choose to live in a neighborhood with more White and fewer Black residents (Emerson et al. 2001). In our sample over time movers, on average, transitioned to neighborhoods with higher percentages of White and lower percentages of Black residents. Panel C in Figure 1 shows this trend, with non-movers living in neighborhoods with the greatest percentages of White residents and movers converging towards this highest percentage.

Finally, parent-reported neighborhood safety suggests improvement over time among movers. Because non-movers were only asked the neighborhood safety question once, we interpret these findings with caution and do not report comparisons in changes over time. However, as illustrated in Figure 1, Panel D, movers showed fairly steep increases in reporting that their neighborhood is very safe from crime. Compared to non-movers in Wave 2, those moving once or twice reported higher levels of safety in Waves 3 and K.

4. Discussion

Like individuals of other ages, early childhood movers and non-movers differ. However, mobility during early childhood appears distinct from moving during other developmental periods. Moving was more common than not among this nationally representative group of families with young children. In contrast, a study by Root and Humphrey (2014) found a smaller proportion of families with children ages 5–10 move. Additionally, the neighborhood contexts of early childhood movers improved relative to non-movers on several dimensions, a trend that differed from that of older children. Residential mobility did not confer any advantages in improving neighborhood context for children ages 5–10 (Root and Humphrey 2014).

Further, our findings suggest that moving can be a successful strategy for improving neighborhood context. Importantly, initially large differences in neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage by move status disappeared or diminished by kindergarten start. Despite these neighborhood improvements, household-level disadvantages for mobile families remained constant across the study period. The relative neighborhood improvements among movers does not appear to be due to increases in household resources, so we speculate that families were either reallocating resources or otherwise strategizing to live in a better location. Thus, neighborhood improvements do not necessarily convey household-level socioeconomic improvement. Without a randomized controlled trial, we cannot determine whether moving would improve the neighborhoods of all families with young children, but it appears to lessen contextual disadvantages for mobile families.

The findings of this study point to early childhood as a distinct life course stage when mobility is common, and future research should examine the motivations for and consequences of early childhood mobility. Such research should consider the life course context of moving, including children’s development and parents’ life course events. The selection processes determining mobility for families with young children differ from those of other families, and the consequences of mobility likely differ as well. Despite the importance of neighborhood context and housing characteristics for child health, little is known about the moving patterns among families with young children. Both the high prevalence and distinct implications of early childhood residential mobility suggest the need for further research.

Acknowledgments

This research is based on work supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (SES 1061058). Research funds were also provided by the NIH/NICHD-funded CU Population Center (R24HD066613). The authors thank Jamie Humphrey for her contributions to this project.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Lawrence, Institute of Behavioral Science and Department of Sociology, University of Colorado Boulder.

Elisabeth Dowling Root, Institute of Behavioral Science and Department of Geography, University of Colorado Boulder.

Stefanie Mollborn, Institute of Behavioral Science and Department of Sociology, University of Colorado Boulder.

REFERENCES

- Anderson S, Leventhal T, Dupéré V. Residential mobility and the family context: A developmental approach. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2014;35(2):70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Busacker A, Kasehagen L. Association of residential mobility with child health: An analysis of the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:S68–S87. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0997-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs V, Morris R. Deprivation and health in Scotland. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press; 1991. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Williamson DF, Dube SR, Brown DW, Giles WH. Childhood residential mobility and multiple health risks during adolescence and adulthood: the hidden role of adverse childhood experiences. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2005;159(12):1104–1110. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson MO, Chai KJ, Yancey G. Does race matter in residential segregation? Exploring the preferences of white Americans. American Sociological Review. 2001:922–935. [Google Scholar]

- Gasper J, DeLuca S, Estacion A. Coming and going: Explaining the effects of residential and school mobility on adolescent delinquency. Social Science Research. 2010;39(3):459–476. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald TL, Karlamangla AS, Hu P, Stein-Merkin S, Crandall C, Koretz B, Seeman TE. History of socioeconomic disadvantage and allostatic load in later life. Social science & medicine. 2012;74(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S. Trajectories of functional health: the ‘long arm’ of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(4):849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Gorman BK. The long arm of childhood: The influence of early-life social conditions on men's mortality. Demography. 2004;41(1):87–107. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0005. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelleyman T, Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(7):584–592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Newman S. Housing and child development. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1165–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder CH, Hooimeijer P. Population issues. Netherlands: Springer; 1999. Residential relocations in the life course; pp. 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B. Moving and children's social connections: Neighborhood context and the consequences of moving for low-income families. Sociological Forum. 2004;19(2):285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Pribesh S, Downey DD. Why are residential and school moves associated with poor school performance? Demography. 1999;36(4):521–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe B, Taylor M. Residential mobility, quality of neighbourhood and life course events. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2010;173(3):531–555. [Google Scholar]

- Root ED, Humphrey J. The impact of childhood mobility on exposure to neighborhood socioeconomic context over time. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):80–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Haynie DL. Friendship networks of mobile adolescents. Social Forces. 2004;83(1):315–350. [Google Scholar]

- Snow K, Derecho A, Wheeless S, Lennon J, Rosen J, Rogers J, Kinsey S, Morgan K, Einaudi P. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth cohort (ECLS-B), kindergarten 2006 and 2007 data file user’s manual (2010-010) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A. Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. London, England: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH., Jr Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. Am J Sociology. 2007;112(6):1886–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest KM, McKenna CC. Early childhood housing instability and school readiness. Child Dev. 2014;85(1):103–113. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]