Abstract

Background:

Free-living amoeba (FLA)-related keratitis is a progressive infection of the cornea with poor prognosis. The present study aimed to investigates the contact lenses of patients with keratitis for pathogenic free-living amoebae.

Methods:

Overall, 62 contact lenses and their paraphernalia of patients with keratitis cultured and tested for the presence of free-living amoebae using morphological criteria. Unusual plates including plates containing mix amoebae and Vermamoeba were submitted to molecular analysis.

Results:

Out of 62 plates, 11 revealed the outgrowth of free living amoeba of which 9 were Acanthamoeba, one plates contained mix amoebae including Acanthamoeba and Vermamoeba and one showed the presence of Vermamoeba. These two latter plates belonged to patients suffered from unilateral keratitis due to the misused of soft contact lenses. One of the patients had mix infection of Acanthamoeba (T4) and V. vermiformis meanwhile the other patient was infected with the V. vermiformis.

Conclusion:

Amoebic keratitis continues to rise in Iran and worldwide. To date, various genera of free-living amoebae such as Vermamoeba could be the causative agent of keratitis. Soft contact lens wearers are the most affected patients in the country, thus awareness of high-risk people for preventing free-living amoebae related keratitis is of utmost importance.

Keywords: Keratitis, Acanthamoeba, Vermamoeba

Introduction

Free-living amoeba (FLA) including Acanthamoeba, Vermamoeba and Vahlkampfia are the opportunistic protist ubiquitous in the nature and they can cause severe threatening keratitis in high-risk people. Poor hygiene in maintenance of contact lens especially soft contact lens and cornea trauma are the major risk factors for FLA keratitis (1–3).

Treatment of amoebic keratitis is usually performed by combination of drugs such as brolene (0.1%), chlorhexididin 0.02% and neomycine. Recently, there are reports regarding effectiveness of polyhexamethylene biguanid (PHMB) for treatment of this devastating corneal infection (4). The problem of treating AK is mainly due to trophicidal activity without efficient cysticidal effect (5–7).

Unfortunately, AK is continued to rise in Iran. Most of the patients were soft contact lens wearers in the country and the majority showed poor prognosis (8). Another study showed an increase rate of AK in the region within young population (9). The majority of patients were treated with brolene and neosporin. However many of them did not respond well to the treatment (8). In a case, which was using contact lens, the patient had a left corneal ulcer for two months, she was treated by various antimicrobial and antiviral agents but she had a lack of response to the antiviral therapy. Immunohistochemistry analysis showed infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages throughout the cornea with Acanthamoeba parasites. The patient was administrated by PHMB and keratoplasty was performed (10).

A case had mix infections of A. polyphaga and Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis due to using soft contact lens, she had a progressively worsening corneal ulcers and did not response to the antibiotics (11). Over 12 months the therapy of the patient continued with 0.2% metronidazole and 0.02% PHMB eye drops. Finally, she went for corneal transplantation (11).

Acanthamoeba T2, T3, T4, T11, Vahlkampfia and Vermamoeba could be the cause of amoebic keratitis in Iran (8, 12–14). The other research among volunteer that used soft contact lens without any eye involvement showed 10% positive for Acanthamoeba T3, T4, T5 and V. vermiformis (15).

The present study aimed to investigates the contact lenses and their paraphernalia of patients with keratitis for pathogenic free-living amoebae.

Materials and Methods

Overall, 62 contact lenses and their paraphernalia of patients with keratitis from hospitals and private clinics referred to the Parasitology Laboratory, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Science, Iran were examined for the presence of free living amoebae using morphological criteria. All samples were cultured on 1.5% non-nutrient agar (NNA) seeded with Esherichia coli bacteria. Morphological analysis revealed that in one plate there was two different amoebae and in another plate Vermamoeba was detected. Thus, cysts of the two latter samples were cloned and DNA extraction was performed by the phenol chloroform method (9). PCR was done with JDP1 (5′-GGCCCAGATCGTTTACCGTGAA-3′) and JDP2 primer (5′-TCTCACAAGCTGCTA-GGGGAGTCA-3′), the primers amplify the ASA. S1 region with approximately 500bp of 18srRNA gene (16). Primers of Vermamoeba spp. was NA1, NA2, the primer amplify partial 18srRNA gene: NA1: 5′-GCT CCA ATA GCG TAT ATT AA-3′ and NA2: 5′-AGA AAG AGC TAT CAATCT GT-3′ (17). PCR assay was performed using the ready-made mixture of Ampliqone (Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix RED, Denmark). Taq Master Mix, template DNA, 0.1 μM of each primer were combined and finally distilled water was added. TECHNE thermal cycler (UK) program was performed, 94 °C for 1 min (initial denaturing) then 35 cycles at 94 °C for 35 s, annealing steps was 56 °C and 50 °C for Acanthamoeba and Vermamoeba respectively, 72 °C for 1 min. Ten min at 72 °C was final extension (18). Electrophoresis of PCR product was carried on 2% agarose gel stained by ethidium bromide and the bands appeared under UV light. PCR products were then sequenced with the ABI 3130X sequencer, sequences were analyzed by using Chromas (version 1.0.0.1) and compared by BLAST. Accession numbers are deposited in GenBank under KP714398 KP714399, KP714400 numbers.

It should be mentioned that the patients with mixed keratitis infection and Vermamoeba keratitis were asked for their symptoms, treatment and improvement during time.

Results

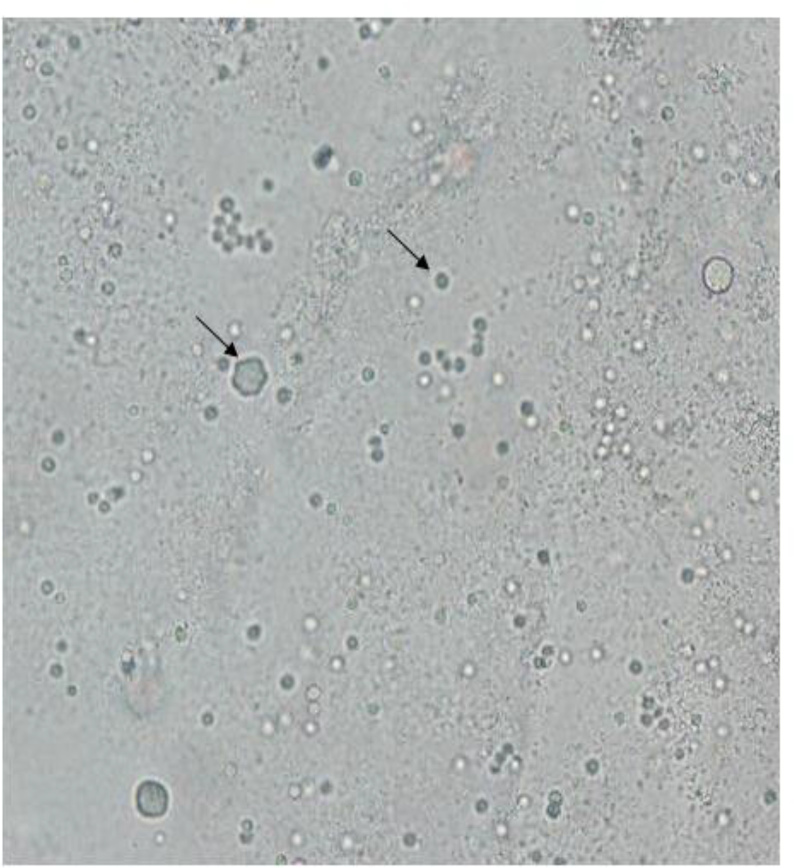

Overall, 11 plates showed growth of free-living amoebae. All patients with amoebic keratitis (11 out of 62) were soft contact lens wearers and their age ranged between 16–27 yr. Only one patient was male and the rest were female. Out of 11 positive plates, 9 contained Acanthamoeba, one plate revealed mix amoebae including Acanthamoeba and Vermamoeba and one showed the presence of Vermamoeba. Regarding the two latter cases, one plate belonged to a 23-yr-old man lived in Karaj (Alborz Province, 20 km west of Tehran). He was a soft contact lens daily wearer for three years and had complaints of eye pain, light sensitivity, foreign body sensation, redness and tearing. He had a severe unilateral keratitis on his right eye. The patient’s symptoms became worst after a month because of misdiagnosis with viral infection and treatment with aciclovir and homatropine eye drops. Later he was referred to the Laboratory of Protozoology in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Morphological survey showed of both Acanthamoeba and Vermamoeba, double-walled cysts with round shape (Vermamoeba), smooth and irregular inner layer of cyst (Acanthamoeba) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Light microscopy image of Vermamoeba vermiformis and Acanthamoeba cysts on non-nutrient agar.

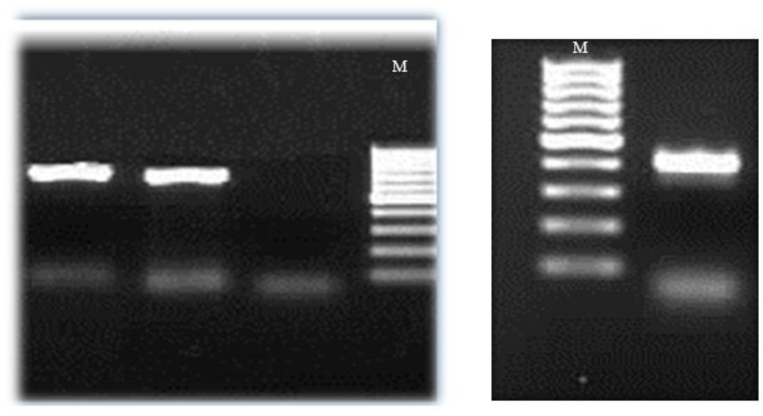

Molecular analysis for both amoebae confirmed the presence of Acanthamoeba belonging to T4 genotype and V. vermiformis (Fig. 1). In addition, PHMB was administered and his symptoms improved in five months.

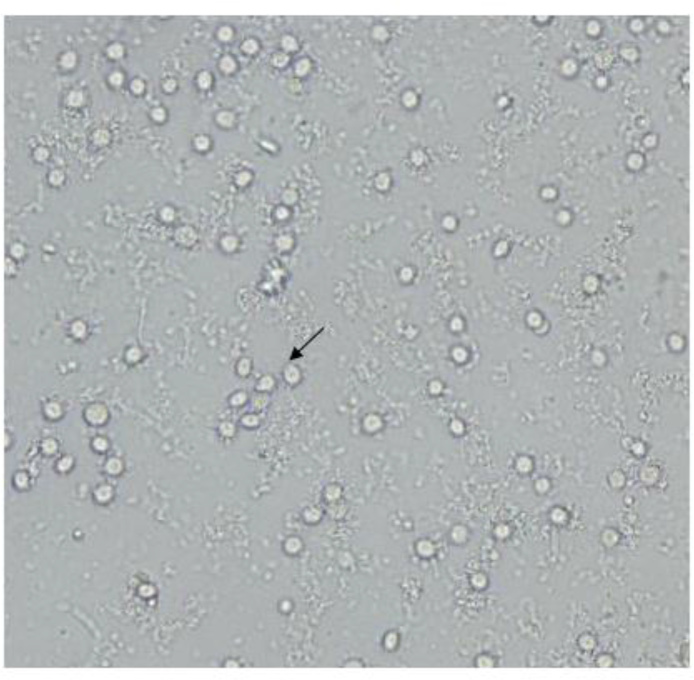

Another plate belonged to a 21-yr-old girl living in Tehran and she was a cosmetic soft contact lenses wearer for three months. The patient was suffering of eye pain, redness, burning, photophobia, foreign body sensation, blurred vision, tearing and reduced vision. She had a keratitis in her right eye because misuse of contact lens and poor hygiene. Contact lens and fluid container were sent to the Laboratory of Protozoology in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Morphological and molecular analysis on the lens and container showed V. vermiformis (Fig. 2, 3).

Fig. 2: Light microscopy image of Vermamoeba vermiformis cysts on non-nutrient agar.

Fig. 3: Gel electrophoresis of the (right): approximately 500 bp PCR product of Acanthamoeba 18s rRNA gene (left): 750 bp PCR product of Vermamoeba vermiformis 18s rRNA gene M: 100 bp Marker.

PHMB (0.02%), drop eyes, was administered for her every 30 min then use of PHMB was gradually reduced and she became healthy during three months of treatment with only PHMB without any relapse.

Discussion

This research reports FLA-related keratitis due to Acanthamoeba (T4) and Vermamoeba. Now, Acanthamoeba contains 20 genotypes based on the diagnostic fragment 3 (DF3) of 18s rRNA gene. According to previous reports, most of highly pathogenic Acanthamoeba belonged to T4 genotypes (12, 19, 20). Indeed T4 genotype produces more cytotoxic factors in comparison to other genotypes such as T2, T3 and T5 and thus the severity of disease will enhance. An increased rate of AK among the contact lens users is reported (8). The exact incidence of AK is not established well due to many unreported cases; however, the AK incidence rate varies between 17 and 70 cases per million contact lens wearers (21).

Interestingly in the present study, cases with mix keratitis and Vermamoeba infection by the early diagnosis and treatment were cured but the male patient had a mix infection, furthermore his treatment was longer with several relapses, however, the female patient had monoinfection with Vermamoeba, so she responded to the therapy faster.

During the recent years in addition to Acanthamoeba, the other FLAs were also reported from keratitis patients (1, 3, 22). There are only a few studies indicate good AK prognosis. One of the reported cases was due to a female contact lens wearer and she showed AK diagnosed by confocal microscopy, she was treated with corneal crosslinking (CXL) successfully (23). The woman, living south east Africa, after diagnosis Acanthamoeba belonging to T13 genotype, was treated with eye drops (propamidine), lavasept (biguanide) and polyspectran eye drops (polymyxin B, neomycin, gramicidin) (24). A previous study also showed effective UV therapy in the amoeba keratitis (25). Other research compared PHMB and chlorhexidine for treatment of AK. The result showed both PHMB and chlorhexidine had similar outcomes (4).

Regarding pathogenesis of Vermamoeba there are several reports due to its pathogenic potential (26–27), a recent study reported the identification of an emerging bacterial pathogen called Mycobacterium chelonae from a V. vermiformis that colonized the nasal cavities of an HIV/AIDS patient (28). Thus, awareness within clinicians should be raised, as pathogenic bacteria such as M. chelonae may be using V. vermiformis to proliferate and survive in the environment (27–28).

Conclusion

Amoebic keratitis continues to rise in Iran and worldwide. To date, various genera of free-living amoebae such as Vermamoeba could be the causative agent of keratitis. Soft contact lens wearers are the most affected patients in the country, thus awareness of high-risk people for preventing free-living amoebae related keratitis is of utmost importance.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Miss. Samira Dodangeh and Dr. Hoda Abedkhojasteh for their kind assistant. This project was granted by Tehran University of medical sciences, Tehran, Iran. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. Aitken D, Hay J, Kinnear FB, Kirkness CM, Lee WR, Seal DV. Amebic keratitis in a wearer of disposable contact lenses due to a mixed Vahlkampfia and Hartmannella infection. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103: 485– 494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Jonckheere JF, Brown S. Is the Free-Living Ameba Hartmannella Causing Keratitis? Clin Infect Dis. 1998b; 27(5: 1337– 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lorenzo-Morales J, Martínez-Carretero E, Batista N, Álvarez-Marín J, Bahaya Y, Walochnik J, Valladares B. Early diagnosis of amoebic keratitis due to a mixed infection with Acanthamoeba and Hartmannella. Parasitol Res. 2007; 102: 167– 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim N, Goh D, Bunce C, Xing W, Fraenkel G, Poole TR, Ficker L. Comparison of polyhexamethylene biguanide and chlorhexidine as monotherapy agents in the treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 145 (1): 130– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen EJ, Parlato CJ, Arentsen JJ, Genvert GI, Eagle RC, Wieland MR, Laibson PR. Medical and surgical treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987; 103: 615– 625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larkin DFP, Kilvington S, Dart JKG. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis With polyhexamethylene biguanide. Ophthalmol. 1992; 99: 185– 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seal DV, Hay J, Kirkness CM. Chlorhexidine or polyhexamethylene biguanide for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Lancet. 1995; 345: 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rezeaian M, Farnia S, Niyyati M, Rahimi F. Amoebic keratitis in Iran (1997–2007). Iran J Parasitol. 2007; 2 (3): 1– 6. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niyyati M, Lorenzo-Morales J, Mohebali M, et al. Comparison of a PCR-Based Method with Culture and Direct Examination for Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Iran J Parasitol. 2009; 2 (4): 38– 43. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knickelbein JE, Kovarik J, Dhaliwal DK, Chu CT. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A clinicopathologic case report and review of the literature. Human Pathol. 2013; 44: 918– 922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hong J, Ji1 J, Xu1 J, Cao W, Liu Z, Sun X. An unusual case of Acanthamoeba polyphaga and Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Diag Pathol. 2014; 9: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Niyyati M, Rezaeian M. Current Status of Acanthamoeba in Iran: A Narrative Review Article. Iran J Parasitol. 2015; 10: 157– 163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Niyyati M, Lorenzo-Morales J, Rezaie S, et al. First report of a mixed infection due to Acanthamoeba genotype T3 and Vahlkampfia in a cosmetic soft contact lens wearer in Iran. Exp Parasitol. 2010; 126: 89– 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abedkhojasteh H, Niyyati M, Rahimi F, Heidari M, Farnia S, Rezaeian M. First Report of Hartmannella keratitis in a Cosmetic Soft Contact Lens Wearer in Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2013; 3 (8): 481– 485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Niyyati M, Rahimi F, Lasejerdi Z, Rezaeian M. Potentially Pathogenic Free- Living Amoebae in Contact Lenses of the Asymptomatic Contact Lens Wearers. Iran J Parasitol. 2014; 1 (9): 14– 19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schroeder M, Booton GC, Hay J, Niszl IA, Seal DV, Markus MB, Fuerst PA, Byers TJ. Use of subgenic 18S ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing for genus and genotype identification of Acanthamoeba from humans with keratitis and from sewage sludge. J Clin Microbiol. 2001; 39: 1903– 1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Solgi R, Niyyati M, Haghighi A, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E. Occurrence of Thermotolerant Hartmannella vermiformis and Naegleria Spp. in Hot Springs of Ardebil Province, Northwest Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2012; 6 (2): 47– 52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lasjerdi Z, Niyyati M, Haghighi A, et al. Potentially pathogenic free-living amoebae isolated from hospital wards with immunodeficient patients in Tehran, Iran. Parasitol Res. 2011; 109: 575– 580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Memari F, Niyyati M, Haghighi A, Seyyed Tabaei SJ, Lasjerdi Z. Occurrence of pathogenic Acanthamoeba genotypes in nasal swabs of cancer patients in Iran. Parasitol res. 2015; 114 (5): 1907– 1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Niyyati M, Nazar M, Lasjerdi Z, Haghighi A, Nazemalhosseini-Mojarad E. Reporting of T4 Genotype of Acanthamoeba Isolates in Recreational Water Sources of Gilan Province, Northern Iran. Novel Biomed. 2015; 3 (1): 20– 4. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lorenzo-Morales J, Martín-Navarro CM, López-Arencibia A, Arnalich-Montiel F, Piñero JE, Valladares B. Acanthamoeba keratitis: an emerging disease gathering importance worldwide? Trend Parasitol. 2013; 29(4): 181– 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inoue T, Asari S, Tahara K, Hayashi K, Kiritoshi A, Shimomura Y. Acanthamoeba Keratitis With Symbiosis of Hartmannella Ameba. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998; 125 (5): 721– 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arance-Gila Á, Gutiérrez-Ortegaa ÁR, Villa-Collar C, Nieto-Bonac A, Lopes-Ferreirad D, González-Méijome JM. Corneal cross-linking for Acanthamoeba keratitis in an orthokeratology patient after swimming in contaminated water. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye. 2014; 37: 224– 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grün AL, Stemplewitz B, Scheid P. First report of an Acanthamoeba genotype T13 isolate as etiological agent of a keratitis in humans. Parasitol Res. 2014; 113: 2395– 2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garduño-Vieyra Leopoldo, Gonzalez-Sanchez Claudia R., Hernandez-Da Mota Sergio E. Ultraviolet-A Light and Riboflavin Therapy for Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Case Report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011; 2: 291– 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reyes-Batlle M, Niyyati M, Martín-Navarro CM, López-Arencibia A, Valladares B, Martínez-Carretero E, Piñero JE, Lorenzo-Morales J. Unusual Vermamoeba Vermiformis Strain Isolated from Snow in Mount Teide, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. NBM. 2015; 4: 189– 92. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pagnier I, Valles C, Raoult D, La Scola B. Isolation of Vermamoeba vermiformis and associated bacteria in hospital water. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2015; 80: 14– 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cabello-Vílchez AM, Mena R, Zuñiga J, et al. Endosymbiotic Mycobacterium chelonae in a Vermamoeba vermiformis strain isolated from the nasal mucosa of an HIV patient in Lima, Peru. Exp Parasitol. 2014; 145: S127– S130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]