Abstract

Background and Purpose:

The efficacy of retigabine (RGB), a positive allosteric modulator of K+ channels indicated for adjunct treatment of partial seizures, was studied in two adult models of kainic acid (KA)-induced status epilepticus to determine it’s toleratbility.

Methods:

Retigabine was administered systemiclly at high (5 mg/kg) and low (1–2 mg/kg) doses either 30 min prior to or 2 hr after KA-induced status epilepticus. High (1 µg/µL) and low (0.25 µg/µL) concentrations of RGB were also delivered by intrahippocampal microinjection in the presence of KA.

Results:

Dose-dependent effects of RGB were observed with both models. Lower doses increased seizure behavior latency and reduced the number of single spikes and synchronized burst events in the electroencephalogram (EEG). Higher doses worsened seizure behavior, produced severe ataxia, and increased spiking activity. Animals treated with RGB that were resistant to seizures did not exhibit significant injury or loss in GluR1 expression; however if stage 5–6 seizures were reached, typical hippocampal injury and depletion of GluR1 subunit protein in vulernable pyramidal fields occurred.

Conclusions:

RGB was neuroprotective only if seizures were significantly attenuated. GluR1 was simultaneously suppressed in the resistant granule cell layer in presence of RGB which may weaken excitatory transmission. Biphasic effects observed herein suggest that the human dosage must be carefully scrutinized to produce the optimal clinical response.

Keywords: Hippocampus, Retigabine, Anticonvulsant, Epilepsy, AMPA receptor, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

A large percentage of patients with partial seizures are unresponsive to presently available second-generation anti-epileptic (AED) drugs. Two-thirds of patients with epilepsy continue to have seizures despite current treatments.1 Additionally, currently available first and second generation AEDs have deleterious side effects such as depression, cognitive impairment, and toxicity.2–5 Patients with epilepsy may also have a propensity for AEDs to interact with other non-AED medications that can lead to difficult clinical management in determining effective and safe polytherapy, particularly for pharmacoresistant patients.6 Therefore, the need for improved medication is in demand, and age must be included as a determining factor for positive long-term clinical response.

Retigabine (RGB) [N-(2-amino-4-(4-fluorobenzylamino)-phenyl)-carbamic acid ethyl ester], a third-generation antiepileptic drug introduced in 2011, appears to represent a reasonable alternative therapy for treating certain types of refractory epilepsy. In human patients, the efficacy and safety of RGB was tested as a monotherapeutic agent at several clinical doses – 600, 900, and 1,200 mg/day – administered three times daily. This experimental approach was formulated to understand the efficacy of RGB as an adjunctive therapy in patients with partial-onset seizures. These studies showed the highest efficacy was achieved at the highest doses.7–9 Retigabine was also reported to be well absorbed and have fewer side-effects than many other recently released drugs such as eslicarbezepine, acetate, rufinamide, lacosamide, and permapenel.10–14 Although there was a recent FDA warning stating that RGB can produce retinal toxicity such as discoloration to the retinal pigment epithelium and blue/grey discoloration of skin, lips, finger nails, and toe nails,15 the most common side effects caused by RGB are central nervous symptoms such as somnolence, dizziness, confusion, and fatigue that diminish with time. This suggests that RGB may still have therapeutic potential that outweighs adverse effects for certain patient populations.

Unlike other AEDs that are Na+ channel blockers, RGB attenuates seizures by a unique feature of opening neuronal K(v) 7.2–7.5 K+ channels.14,16,17 Specifically, RGB is the first described M-channel agonist which binds to the cytoplasmic aspects of the S5 and S6 parts of the activation gate of K+ channels involved in M-currents. RGB binding maintains K+ channels in an open state for longer periods of time and increases the probability of further channel opening.18,19 Pharmacological studies also demonstrate that by acting as a positive allosteric modulator of KCNQ2-5 (K[v] 7.2–7.5) ion channels, RGB also circumvents cardiac side-effects.19,20 Additional studies have validated anticonvulsant effects produced by RGB in animal models of epilepsy carried out in mice and developing rats.21–24 For example, one study, conducted in ex-vivo entorhinal cortical-hippocampal slices derived from either control or KA-treated rats, illustrated a dramatic reduction in spontaneous bursting frequency with RGB application, whereas pharmacoresistance was observed with other AEDs such as lamotrigine (LTG) and valproate (VPA).25 Anticonvulsant effects were also observed in development after rapid kindling epileptogenesis24 and in conjunction with pentylentetrazole (PTZ) seizures, having higher efficacy with increasing age.22

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors are encoded by a gene family that are heteromeric complexes of four homologous subunits designated GluR1 to GluR4 (or GluRA-D) and are responsible for rapid excitatory neurotransmission.26,27 Previously, we examined these receptors in mature and immature rats at acute times following kainic acid (KA)-induced status epilepticus.28 We found fairly steady levels of the GluR1 subunit in adults 24 hr after the KA insult.29 These levels were found to exist prior to the extensive cell loss of adults, whereas prepubescent rats exhibit GluR1 depletion in the CA1 at 3 days after status epilepticus when injury typically first becomes apparent.30,31 Here we tested, in adult rats, several systemic doses of RGB on the efficacy of KA-induced status epilepticus to estimate the seizure threshold as well as potential distribution effects on the expression of the GluR1 subunit at longer delayed time points and following chronic RGB treatment.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley adult rats (200–250 gr) (Charles River, St Louis, MO, USA) were used. Animals were housed in single cages and were given food and water ad libitum until sacrifice. All animals were kept on a 12-hr light/dark cycle at room temperature (55% humidity) in our New York Medical College (NYMC) accredited animal facility. The work described has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association and all animal procedures were in accordance with NIH guidelines approved by NYMC and GlaxoSmithKline internal Animal Ethical Committees. Animals were divided into control and experimental groups as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental design

| Groups | Intraperitoneal (N) | Intrahippocampal (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 8 | 6 |

| KA | 9 | 8 |

| RGB+KA | 31 | 8 |

| KA+RGB | 18 | _ |

| RGB | 7 | 2 |

KA was administered by intraperitoneal or intrahippocampal injection to adult Sprague Dawley rats. RGB was administered either prior to or after KA-induced seizures at various doses to test the acute efficacy of RGB in an animal model of limbic seizures. KA, kainic acid; RGB, retigabine

Drugs

RGB was synthesized and donated by GlaxoSmithKline. RGB stocks of 20 mg were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (100%) and then diluted by 50% to 20 mg/mL and further diluted to a 5 mg/mL stock. The final concentration of DMSO was ≤ 10%. To evaluate the anticonvulsant effect of RGB, varied doses were tested prior to and after administration (15 mg/kg). Control animals received vehicle (DMSO, 10% in phosphate buffered saline [PBS]) (N=8). There were four experimental conditions: (1) Stage 6 seizures were induced with KA by intraperitoneal or intrahippocampal injection (Table 1). (2) To determine the efficacy of peripheral administration, RGB was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) once at various doses (1, 2, 5, 10, 100 mg/kg) (N=3, 6, 17, 3, 2) 30 min prior to injection of KA. In addition, RGB was administered by i.p. injection twice, 24 hr and 30 min prior to KA injection (N=9). (3) Two hr post-KA injection, animals received RGB at three doses (1, 2, and 5 mg/kg) (N=4, 5, 9). (4) RGB was administered at 5 mg/kg for 14 consecutive days (N=7). Experimental and controls groups were sacrificed at 1, 3, or 28 days after status epilepticus.

Induction of status epilepticus and seizure scoring

Status epilepticus was induced with KA intraperitoneally (15 mg/kg). As previously described, a modified Racine method was used to assess seizure severity.29 Seizure behaviors were scored on a scale of 0–7, with 0 representing normal behavior and 7 representing death. Stage 1=mild scratching, hyperexcitability; Stage 2=continuous scratching, soft head nods; Stage 3=wet dog shakes, and occasional rearing; Stage 4=salivation, wet dog shakes and unilateral clonus of forepaw; Stage 5=recurrent wet dog shakes, rearing and/or standing tonus, and bilateral clonus of forepaws; Stage 6= tonic-clonic seizures, heavy drooling and frothing, rearing with forelimb clonus with continuous head bobbing, circling, and running, and/or loss of postural control. These typical behaviors were recorded after early signs emerged (e.g. scratching), and seizure behavior scores were calculated for each animal. Stages 1–2 were classified as nonconvulsive; stages 3–6 were classified as convulsive as these stages were associated with epileptiform events in the electroencephalogram (EEG). After the onset to behavioral seizures (∼60 min), the number, frequency, and duration of different seizure behavior manifestations were recorded every 5 minutes for 3 hr. Approximately 90% of KA-injected animals in the absence of RGB reached stage 5–6 seizures that lasted for at least one hr. After 24 hr, half of stage 5–6 seizure animals received RGB systemically (2 mg/kg) once daily for 14 days. An equal number of injections of RGB were administered to a separate group for comparison.

Electrode implantation for EEG recordings

Acute EEG recordings were obtained from KA and RGB+KA treated groups. First, all subjects were anesthetized with a mixture of 70 mg/kg ketamine and 6 mg/kg of xylazine. They were then stereotaxically implanted with either bipolar electrodes or dual bipolar electrode/cannula assembly into the right hippocampus 48 hr prior to KA or RGB+KA treatments (coordinates in mm with respect to bregma: AP: −3.4; L: 2.6; D: −3.0; incisor bar at −3.5).32 The electrodes were perpendicularly oriented, angled at 0° from the vertical plane. After surgery, dental acrylic was used to close the wound and stabilize the electrode assembly. Rats recovered from anesthesia and became active 1–2 hr following the surgery. Animals were maintained at 30°C in a clean cage box under an incandescent lamp and then returned to their cages until testing. In order to obtain EEG recordings, KA and KA+RGB treated animals were paired, placed in an insulated chamber, and connected to the recording set up through flexible low noise leads (Plastics One), which permitted free movement.33 Baseline EEG recordings were obtained from KA and RGB+KA treated animals for 2 hr following drug administration. For offline analysis, Data Wave software was used to quantify wave frequency, amplitude, and number of spike and burst events in the EEG traces. The program uses digital filtering with a Butterworth 3 pole filter and a 6 dB per octave roll-off. EEG traces were filtered prior to being subjected to burst, Fourier, and spectral analyses to quantify changes in oscillation frequency and duration. The EEG spectral power was monitored from six frequency bands: delta (0.1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), low-gamma (30–70 Hz), and high-gamma (70–180 Hz). Epileptic spike discharges were recorded in the low and high gamma range. PBS/DMSO-injected control rats were also used for baseline comparison (N=3). Electrode placement into the CA1 was verified histologically with Nissl staining.

Injury assessment

Cresyl violet Nissl staining method was carried out on fixed serial air-dried sections (40 μm) from brains processed for neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) and GluR1 immunohistochemistry. Histology included different levels of the hippocampus along the septotemporal axis and associated areas for qualitative analysis of obvious cell loss in the CA1 or CA3 sublayers. NeuN, a specific neuronal cell marker,34 was simultaneously used to monitor neuronal injury and/or cell loss from the same animals. Nissl and NeuN labeled sections were mounted, processed through graded ethanols, and cleared with three changes of xylene for 15 min each. Sections were viewed and photographed under bright-field optics and phase contrast according to the rat atlas.32 At least 9–12 sections per animal were photographed with a CCD camera interface to a Dell computer equipped with Pro-Image software. Objectives were first calibrated with a 1 mm ruler (100 × 0.01). Due to the widespread and variable injury observed in young adult Sprague Dawley rats, using a guide reticule under light microscopy, the CA1 and CA3 areas from each animal were first ranked on an injury scale based on ruler length, ranging from 0 – 4: 1=0.2–1.0 μm; 2=1.1–2.2 μm; 3=2.3–3.5 μm, and 4 ≥ 3.6 μm. Subregion rankings were averaged to one total score per animal and subjected to non-parametric statistics. Injury was also computed from parametric linear measurements averaged from the hippocampus of both hemispheres. After scanning the sections, line tools were then used to draw a line between and/or around the endpoints of the injured areas. The distance and area between those points were calculated and averaged from at least 3–4 sections at 3 hippocampal levels spanning the CA1 and CA3 subfields (∼2.36 ± 0.41 mm3) as described.35 Cell counts of injured vs. surviving cells of the hippocampal pyramidal fields were also assessed. To avoid overlap of cell counts, the number of NeuN and Nissl stained cells were measured from the dorsal hippocampus from at least 3–4 coronal sections per level per animal as above. Numbers of healthy and injured appearing cells were averaged from each area relative to controls and mean averages were subjected to statistics.

Immunohistochemistry

Chromogen-based immunohistochemistry with commercially available antibodies (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was utilized according to standard protocols at the level of the hippocampus.31,36 To minimize pain and discomfort, animals were first anesthetized with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and perfused intra-aortically with ice cold 0.9% saline followed by 200 ml 4% PFA prepared in PBS. Brains were removed, blocked, and post-fixed for 15 hr at 4°C and then transferred to PBS. Serial free-floating coronal vibratome sections (40 μm) were subsequently prepared from posterior to anterior levels and collected in two 24 well flat culture dishes yielding approximately 48 sections per animal. Sections were randomized by alternately selecting sections for each antibody from 4 hippocampal levels (every 5th and 15th section between −2.4 and −4.6 mm from Bregma).32 Sections were washed in PBS (2×) and then incubated with 0.5% H2O2 for 30 min to remove endogenous peroxides. Brain sections were washed (4× for 10 min each) and then followed by immersion in blocking solution (5% horse serum/0.5% bovine serum albumen [BSA]-PBS) for 1 hr at room temperature. NeuN immunohistochemistry (Millipore, MA) was carried out at 1, 3 and 28 days (n=3–6 /group) to monitor injury and for estimating total numbers of surviving neurons of the hippocampal subregions. GluR1 immunolabeling was simultaneously carried out in serial sections. Primary antibodies were diluted (1:200 and 1:1000, respectively) and added to brain sections for 48 hr at 4°C. Next, sections were washed (3× for 10 min each) in PBS to remove the primary antibody. Secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (diluted 1:200) was added (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and incubated for 2 hr at room temperature. After three washes, ABC solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was added for 1 hr at room temperature. For visualization, the sections were reacted with 3′, 3-dia-minobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (5 mg/mL and 0.001% H2O2) (Sigma, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and then washed, mounted, dehydrated, cleared, coverslipped, and viewed under bright-field optics and phase contrast.

Immunodensity measurements

Sections randomized from the immunohistochemistry setup were scanned with a digital spot camera attached to an Olympus BX51 microscope interfaced with a Pentium IV DELL computer. All camera settings were held constant during image capturing. Immunodensity values for GluR1 protein were extracted from both hippocampal hemispheres, and optical density (OD) measurements using updated NIH image software was engaged. Mean values were averaged to obtain total immunodensity means in control and experimental groups. Since sections may label non-uniformly due to variability in perfusions, at least 4 slides were prepared from all animals. Three to four sections were mounted 12–15 sections apart to capture different levels of the hippocampus and avoid cell overlap. Several areas were used for subtracting background signaling – the neuropil, corpus collosum, and glass slide with no tissue – to obtain raw values. Since lesion size varied from section to section and animal to animal, raw OD values were first randomly taken from each area by tracing around the entire subfield that included the injured areas. Measurements were compared to the vehicle control and RGB prolonged treatment groups. Background values were averaged and subtracted from each of the hippocampal areas. Variations in immunodensity measurements were normalized, calculated in percentage relative to the control group (e.g. CA1KA/CA1control). Since vibratome sections label non-uniformly, internal ratiometric calculations were also carried out on the surviving regions that excluded the lesion. Experimental section values were normalized to the dorsal portion of the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (e.g. GLCKA/DG dorsal molecular layer [DML]control) from the same section as this was the only steady hippocampal area of labeling which allowed us to avoid areas devoid of tissue staining as the common background. Thusly, the DML served as the most efficient internal control to manage variable labeling that occurs between sections from the same animals. Values were then averaged from different sectors from the same animal to generate one ratio per animal per area.

Statistics

Significant differences were determined for all groups. Results are given as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Numbers assessed from measuring the area of injured cells after Nissl staining or NeuN labeling values were subjected to One-way analysis of variance (ANOVAs) using Sigma Stat software (Sigma Plot, 12.0, Systat Software, Inc., CA, USA). The Holm-Sidak Test was used for pairwise multiple comparisons because this method is more powerful than the Tukey and Bonferonni tests for measuring differences between groups with unequal sample sizes. EEG and immunodensity measurements for all groups were also subjected to One-way ANOVA. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), Mann Whitney U, and t-tests were used to compare the relationships among injury, seizure severity, and GluR1 immunodensity. Significance was set at p<0.05 for all tests.

Results

Seizure behavior

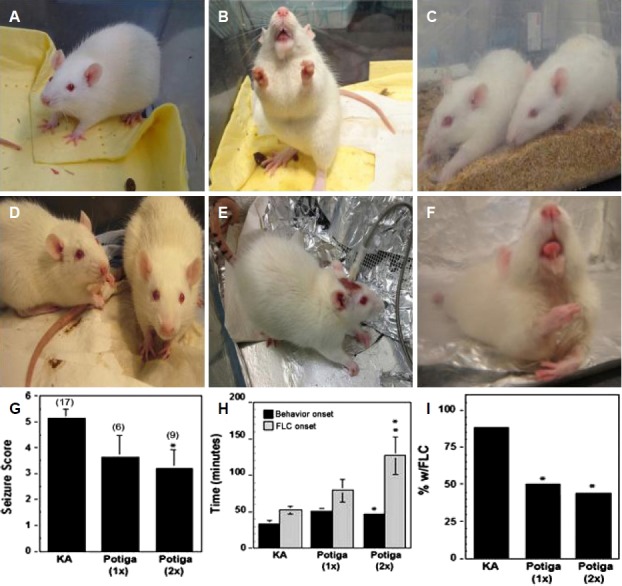

Pre-treatment with RGB doses ≥ 10 mg/kg produced deep, rapid sedation and was therefore discontinued. In contrast, lower doses of 1, 2, or 5 mg/kg did not produce obvious sedative signs or loss of posture and locomotion (Fig. 1A). All animals receiving KA in the study exhibited typical status epilepticus behavior such as drooling and salivation, circling, and rearing with forelimb clonus (FLC) (Fig. 1B). A single injection of 1, 2, or 5 mg/kg administered 30 min prior to KA injection delayed the onset to seizure behavior but was insufficient to eventually prevent the induction of status epilepticus or affect the overall averaged seizure score (Fig. 1G). However, the highest dose, 5 mg/kg of RGB, resulted in a significant reduction or absence of stage 5–6 seizure behavior symptoms in ∼50% of the animals (Fig. 1I). In addition, two prior treatments of 5 mg/kg of RGB (24 hr and 30 min prior to KA injection) significantly increased seizure behavior latency and reduced stage 5–6 symptoms (Fig. 1C and H). When RGB was administered 2 hr after the KA injection, during status epilepticus, 2 mg/kg of RGB quickly calmed seizure behavior (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the higher dose of 5 mg/kg of RGB injected 2 hr post status epilepticus unexpectedly worsened seizure severity. These animals lost postural control, laid flat in prone position, and exhibited severe drooling with protruded tongue as well as continuous FLC compared to the occasional behaviors displayed by the KA-only treatment (Fig. 1B, E, and F).

Figure 1.

Biphasic effects of RGB before and after administration of KA. (A) RGB treated animal (5 mg/kg) is alert. (B) KA treated animal exhibiting a stage 6 seizure; foaming, rearing and forelimb clonus. (C) One treatment of RGB (5 mg/kg) 30 min prior to KA injection: Left rat has tonic convulsions without reaching stage 5–6; right rat is resistant to the seizure. (D) Two treatments of RGB (2 mg/kg) 2 hr post KA: both rats are calm and seizure free. (E) KA treatment prior to RGB injection exhibits arched back and postural control. (F) The same animl shown in panel E received a post-injection of RGB (5 mg/kg): This animal became ataxic and exhibited drooling with tongue held out, body tonus, and loss of postural control resembling a severe proconvulsant effect. (G) Graphical analysis of seizure scoring showed 2 prior treatments were more effective than one. (H) Seizure behavior onset and incidence of forelimb clonus (FLC) was significantly delayed or attenuated with two prior treatments of RGB. (I) RGB also reduced the percentage of animals with stage 5–6 seizure behavioral symptoms such as drooling, rearing, and FLC. 1×=one injection and 2×=two injections of RGB. KA, kainic acid; RGB, retigabine.

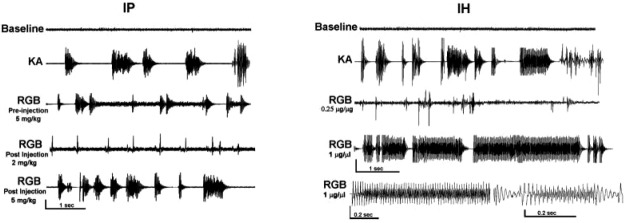

EEG activity: systemic vs. intracrainal

EEG recordings following i.p. KA administration vs. intrahippocampal microinjection (i.h.) in the presence and absence of high vs. low doses RGB are illustrated (Fig. 2). Baseline activity was of low amplitude and asynchronous (Fig. 2, top traces). KA i.p. treatment resulted in delayed spike onset at 16.17 ± 3.66 min. The onset of spikes and high frequency bursts were also delayed, arising at 36.68 ± 6.73, and continued for the remainder of the recording period (2 hr). In contrast, microinjection of KA by i.h. administration resulted in rapid spikes within seconds (10.13 ± 1.7 sec), and low amplitude burst activity initially occurred within 0.995 ± 0.17 min, while delayed bursts of high amplitude were observed at 18.18 ± 2.89 min (Table 2 and Fig. 2, second trace on left). Continuous high amplitude sharp wave and bursts of high frequency oscillations appeared at 18.18 ± 2.89 min. Sharp wave burst events continued throughout the remainder of the recording period, resembling the KA (i.p.)-treated group. Except for the onset to spike or small burst activities, offline analysis revealed no significant differences in the EEG traces between intraperitoneal vs. intrahippocampal KA administration in the absence of RGB; rhythmic oscillations and burst activity with high amplitude spikes were of similar duration (Table 2). Consistent with behavioral observations systemic pre-injection of RGB (5 mg/kg) further delayed the onset of spike activity. Synchronous spiking in the EEG as well as bursts were attenuated displaying smaller amplitudes and shorter burst duration (Fig. 2, third trace, Table 2). Post-KA-injection of a lower dose of RGB (2 mg/kg) administered during status epilepticus, greatly attenuated spike and burst activity; single spikes of lower amplitude were observed and high frequency bursting was diminished (Fig. 2, fourth trace). The higher dose of 5 mg/kg of RGB increased the number of single spikes and bursts as well as duration of burst activities (Fig. 2, fifth trace). Similarly, a biphasic effect was observed with focal microinjection of KA+RGB (Fig. 2, right panels). Although the onset to spikes was not altered with direct application to the CA1 region, the lower dose of 0.25 μg/μL significantly reduced spike and burst frequency and amplitude of initial and subsequent spiking. Several animals did not display any burst activity, only a range of single spikes, predominantly of low amplitude (∼0.1–0.5 mV). In contrast, the higher dosage of 1 μg/μL of RGB in presence of KA significantly amplified the frequency and duration of burst activity (Fig. 2, third and fourth traces Table 2).

Figure 2.

EEG tracings after systemic or intrahippocampal KA ± RGB. Intraperitoneal treatment (IP): Left panels: Baseline activity; typical KA induced spikes and burst oscillations; pre-injection of RGB (5 mg/kg) reveals partial attenuation of spikes and bursts; post-injection of RGB (2 mg/kg) diminished synchronous spike and wave activity 2 hr after administration, anti-epileptic dosage; pro-convulsant and ataxic effect of RGB on KA seizures were found at a higher dose (5 mg/kg) when administered 2 hr after KA injection. Intrahippocampal treatment (IH): Right panels: Baseline activity; typical KA induced spikes and burst oscillations; RGB (0.25 μg/μl) reduced or prevented KA-induced epileptiform activity; RGB (1.0 μg/μl) enhanced KA-induced epileptiform activity; lower trace shows expansions of burst oscillations. EEG, electroencephalogram; KA, kainic acid; RGB, retigabine.

Table 2.

Quantification of EEG recordings

| Treatment | Spike onset (min) | Amplitude (mV) | Burst onset (min) | Burst frequency (Hz) | Burst duration (sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA (i.p.) | 16.17 ± 3.66 | 3.14 ± 0.44 | 36.68 ± 6.73 | 1.27 ± 0.36 | 1.88 ± 0.34 |

| Retigabine 5 mg/kg (pre-injection) | 46.04 ± 11.85* | 0.391 ± 0.25 | 22 ± 2.2 | 0.45+0.69* | 0.94 ± 0.26 |

| Retigabine 2 mg/kg (post-injection) | - | 0.032 ± 0.024* | 18.7 ± 4.58 | 0.12 ± 0.01** | 0.62 ± 0.54* |

| Retigabine 5 mg/kg (post-injection) | - | 3.51 ± 0.32 | 43.26 ± 5.31* | 4.97 ± 1.02** | 1.48 ± 1.67 |

| KA (i.c.) | 0.16 ± 0.028 | 4.01 ± 0.55 | 18.18 ± 2.89 | 1.49 ± 0.40 | 0.89 ± 0.14 |

| RGB (0.25 μg/L)+KA | 0.18 ± 0.068 | 0.863 ± 1.66 | 28.47 ± 4.08** | 0.03 ± 0.21** | 0.22 ± 85 |

| RGB (1 μg/L)+KA | 0.80 ± 0.36 | 3.64 ± 0.48 | 11.9 ± 1.68** | 2.15 ± 0.32* | 1.33 ± 0.12* |

KA was administered by intraperitoneal or intrahippocampal injection to adult Sprague Dawley rats and EEG recordings were performed with in-depth hippocampal electrodes. Lower doses were anticonvulsant, whereas; higher doses were proconvulsant. The onset to spike activity was delayed with i.p. administration; attenuation of spike and wave activity was observed with either route of injection. Due to a wide range of spike amplitudes EEG amplitude was measured within a range to exclude signals below 0.1 mV or above 18 mV. Bars are means ± SEM of 90 min of tracing per animal per group.

p<0.05,

p<0.01. EEG, electroencephalogram; KA, kainic acid; RGB, retigabine

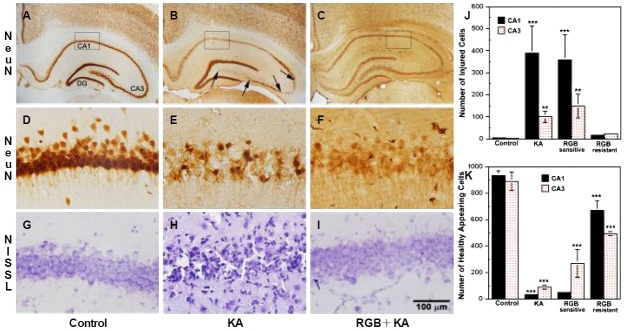

Injury assessment

Cresyl violet and NeuN immunostaining were used to estimate the linear extent of injury or cell loss in KA and RGB+KA treated groups. At 24 hr, only subtle injury was observed after either treatment, usually within the CA3a of the CA3 subregion, similar to prior findings.29 At 3 (not illustrated) or 28 days (Fig. 3), animals scored with stage 6 seizures exhibited similar and extensive hippocampal injury irrespective of treatment. Seizure scores and linear injury measurements were positively correlated (KA: r=0.863, p <0.05; RGB+KA: r=1.0, p <0.001). Three patterns of hippocampal injury were observed: (dual injury 1), the CA1 exhibited extensive amounts of injured cells; thinning and small gaps were noted within the layer including the subiculum; the CA3 tended to have large gaps of missing cells or neuronal remnants were highly necrotic (Fig. 3A–B, D–E); (dual injury 2), the CA3 had large gaps that was associated with massive hilar cell loss but the CA1 was spared; or (single injury), the hilus had massive cell loss but in the absence of obvious CA1 or CA3 damage. After KA, only 2 of 17 animals exhibited the dual injury 1 pattern, whereas 8 animals exhibited the 2nd pattern of injury, 3 had hilar injury only and 4 had extensive injury in all three subregions. In contrast, 83% of RGB+KA treated animals had injury predominantly within the CA1 with CA3 sparing; only 1 of 9 had injury in all three subregions both of which were less than that observed after KA treatment. The difference in the median ranked injury values was significantly higher in animals treated with KA compared to RGB+KA (KA: 5.5 vs. RGB: 2.0, Mann-Whitney statistic=4.5, p <0.05; mean values: t-test: 7.00 ± 1.15 vs. 2.667 ± 1.483, p <0.05). In RGB+KA resistant rats, linear parametric measurements of the lesion size confirmed neuroprotection at both time points (3 and 28 days) (CA1: KA+retigabine 0.065 mm2 ± 0.025, CA3: KA+retigabine 0.109 ± 0.066, p <0.01). In contrast, non-resistant KA+retigabine treated rats from both time points resembled KA treated groups (CA1: KA: 0.269 ± 0.036 mm2 vs. KA+retigabine 0.29 mm2 ± 0.085, CA3: KA: 0.106 ± 0.03 vs. KA+retigabine 0.114 ± 0.04). Counting the number of injured cells at 3 days after KA or RGB injections revealed that there was significantly lower numbers of injured cells found in CA1 and/or CA3 subegions in RGB resistant to seizure animals but not in RGB non-resistant animals (Fig. 3J). In addition, the number of healthy appearing cells increased in RGB resistant animals however; significantly less was counted compared to controls (Fig. 3K). At 28 days, injured appearing neurons were absent but the number of healthy appearing neurons was similar to that observed at 3 days consistent with linear measurements. The CA3 was more preserved compared to the CA1 in RGB resistant animals (healthy appearing neurons expressed as percent of control: KA: CA1: 51.4 ± 15%; CA3 38.4 ± 8% vs. RGB: CA1: 68.9 ± 8.7; CA3 102 ± 5.2%, p <0.01). Animals treated with RGB daily for 14 days followed by 24 hr of withdrawal displayed no obvious injury under bright field microscopy resembling the control (Fig. 3I).

Figure 3.

Histological examination 28 days after KA ± RGB treatment at the level of the hippocampus. (A, D), Control NeuN labeling was intense and uniform throughout the hippocampal subfields; high magnification of CA1 labeled neurons showed they were round and healthy (400×). (B, E), After KA (15 mg/kg, i.p.), extensive cell loss was observed throughout the CA1, CA3, and hilar subfields (between arrows); the DG and CA2 were relatively resistant. High magnification revealed fewer, shrunken CA1 neurons throughout the layer; CA3 and hilar neurons were shrunken or absent. (C, F), Partial injury to CA1 and CA3 neurons was revealed after 2× RGB (5 mg/kg, i.p.) followed by KA; high magnification presented many healthy neurons. (G), Nissl staining of control animal labeled healthy, round CA1 neurons. (H), Nissl staining of KA animal revealed marked injury to CA1 neurons. (I), RGB+KA animals that were resistant to seizures displayed little or no injury, resembling the controls. (J, K), Graphic analyses of the number of injured vs. healthy appearing pyramidal cells at 3 and 28 days following systemic injections of both groups of animals that were either sensitive or resistant to seizures. Bars represent the mean averages ± SEM. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. One Way ANOVA. Scale=100 μm. KA, kainic acid; RGB, retigabine; DG, dentate gyrus; NeuN, neuronal nuclear antigen.

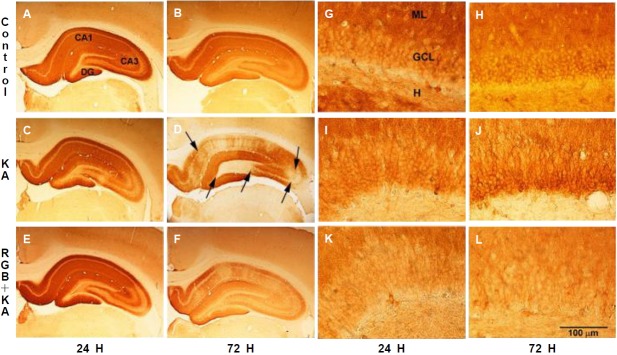

GluR1 receptor subunit protein expression

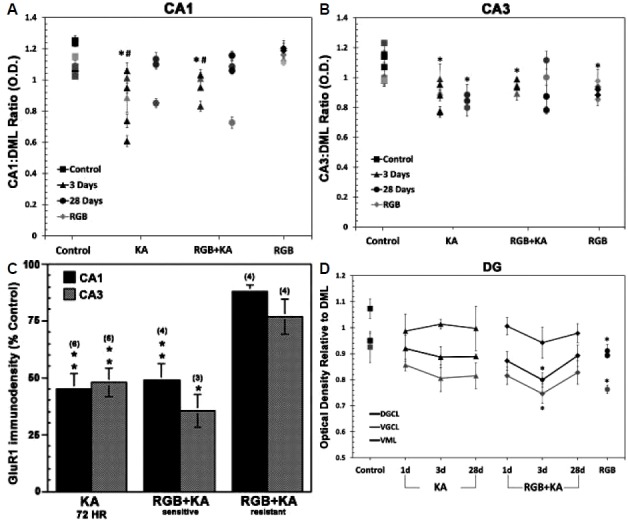

To determine whether RGB affected the expression of AMPA receptors, brain sections were analyzed immunohistochemically with a GluR1 subunit specific antibody. In controls, GluR1 immunoreactivity was relatively uniform and dense throughout all layers of the hippocampus as described36 (Fig. 4A–B). At 24 hr, GluR1 subunit expression was steady throughout the hippocampal subfields in animals treated with KA or RGB+KA, except the CA3 subregions showed a decreased trend of expression consistent with our previous report (Fig. 4C, E). Within the dentate gyrus (DG), GluR1 subunit expression was dense and uniform in molecular (ML) and granule cell layers (GCL) of the dentate gyrus of control animals treated with vehicle and single (Fig. 4A–B, G–H) or multiple injections of RGB (not illustrated). GluR1 labeling of the dorsal blade of the ML remained steady, similar to the vehicle control group at all times points examined. At 72 hr, significant decreases in GluR1 expression were observed after KA or RGB+KA within both CA1 and CA3 subregions relative to vehicle controls, which were commensurate with hippocampal injury (Fig. 4D). Within the DG, transient decreases in GluR1 subunit expression were observed within the GCL and ventral molecular layer (VML), of RGB+KA-treated animals but not in KA-treated animals (F=5.2, p =0.007 vs. F=3.38, p=0.037, respectively) (Fig. 4G–L).

Figure 4.

GluR1 immunohistochemistry in presence and absence of RGB treatment illustrated at two magnifications (20×, 400×). (A, G) GluR1 control immunolabeling was intense and uniform. (B, H) GluR1 expression was stable after RGB treatment in the absence of KA. (C, I) At 24 hr after KA, GluR1 was steady in the CA1 and DG but reduced in the CA3 within areas of cell damage. (D, J) At 72 hr, GluR1 immunolabeling was depleted in the CA1/subiculum and hilus in areas of cell loss but spared in survival regions. (E, K) At 24 hr after RGB+KA treatment, GluR1 protein was stable. (F, L), At 72 hr, GluR1 was reduced in areas of injury, similar to the KA treatment and reduced GluR1 expression was observed within the GCL. Scale=100 μm. RGB, retigabine; KA, kainic acid; GCL, granule cell layer; ML, molecular layer; dentate gyrus.

Densitometry measurements that included both surviving and damaged regions revealed decreases in GluR1 expression in either CA1 or CA3 subregions were greater after KA treatment or in animals treated with RGB but still sensitive to KA (Fig. 5A). In contrast, RGB treated rats that were resistant to KA seizures displayed higher GluR1 levels more closely resembling the controls (Fig. 5A–B). At 24 hr, lesions were small or absent and total GluR1 immunodensity measurements were at 90 ± 4.2.% of control levels in CA1 and DG subregions and at 87 ± 3.6% of control levels in the CA3 subregion. At 72 hr, decreases in GluR1 were >50 percent when lesions were apparent (Fig. 5C). Animals treated with RGB+KA also had steady GluR1 levels at this time; however, the ventral granule cell layer (VGCL) showed a trend of decline at 87.9 ± 7.2% of the control (p =0.08). Ratiometric calculations of the surviving areas (with the DML as the denominator) revealed variability between subjects similar to NeuN and Nissl staining patterns (Fig. 5B–D). The CA1 had the largest most wide spread reduction in the OD ratio (Fig. 4D, F, and Fig. 5A, C). Within the DG, GluR1 reduction was observed within the dorsal and ventral GCL; values are expressed as percent of control (KA; CA1: 76.908 ± 7.041%, CA3: 81.373 ± 3.704%, DGCL: 93.324 ± 4.054%, VML: 94.414 ± 1.792%, VGCL: 87.066 ± 5.145%; (RGB +KA; CA1: 84.002 ± 4.467%, CA3: 87.08 ± 1.97%, DGCL: 84.119 ± 2.721%, VML: 87.789 ± 5.984%, VGCL: 80.642 ± 3.752%). At 28 days, GluR1 levels were steady except in areas of cell loss where depletions were ≤ 20% following KA or RGB+KA. In contrast, the CA3 was still significantly suppressed within surviving areas in KA-treated but not RGB+KA-treated rats (Fig. 5A–C). Data expressed as percent of control OD ratio (KA: CA1: 90.354 ± 8.91%, CA3: 78.032* ± 2.489%, DGCL: 93.564 ± 0.879%, VML: 92.888 ± 8.586%, VGCL: 88.066 ± 4.962%); RGB+KA: CA1: 88.559 ± 9.578%, CA3: 87.419 ± 7.314%, DGCL: 93.922 ± 4.156%, VML: 91.151 ± 3.686%, VGCL: 89.421 ± 4.509%). Daily treatment of RGB for 14 days in the absence of KA and followed by a 24-hr delay also resulted in reduced GluR1 expression which was predominant in the CA3 subregion. At 28 days in animals treated daily for 14 days with RGB that were resistant to the KA-induced injury there was a significant reduction in GluR1 expression within the ventral ML relative to the dorsal ML of the DG (F=4.47, p =0.014) (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

(A) GluR1 Densitometry measurements of both surviving and damaged regions show marked decreases in both CA1 and CA3 subregions at 3 days. (B) Within subject ratiometric analysis of GluR1 immunodenistometry of the spared regions is illustrated at 3 and 28 days after KA ± RGB treatment. Ratiometric mean averages were significantly decreased throughout the CA1 subfield at 3 days after KA ± RGB. Variable GluR1 expression was observed at 28 days; some had marked depletions that were commiserating with cell loss. Chronic RGB treatment did not alter CA1 expression. (C) GluR1 expression of the CA3 was less variable than CA1; ratiometric mean averages were significantly decreased throughout the CA3 subfield at 3 and 28 days after KA ± RGB. Chronic RGB treatment also reduced GluR1 expression of the CA3 in the absence of KA. (D) Within the GC, GluR1 expression significantly declined after RGB+KA and after chronic RGB treatment in the absence of KA. *p<0.05, One Way ANOVA. GLC, granule cell layer; DML, dorsal molecular layer; KA, kainic acid; RGB, retigabine; DG, dentate gyrus.

Discussion

Voltage-gated K+ channels underlie M-currents (IM) and regulate sub-threshold electrical excitability, axonal excitability, and neurotransmitter release of several different types of neurons.19,37 They are characterized by unique features such as a negative activation range, reduced spike threshold, slow activation and deactivation, or no inactivation ability.37–41 Additionally, in vitro models have shown that RGB may act as a positive modulator on GABAA receptors, though it does not directly act on glutamate receptors.42–44 The objective of this study was to examine the efficacy of the K+ channel opener, RGB, on the seizure threshold in two experimental models of partial limbic seizures induced with KA (systemic vs. intrahippocampal).

Consistent with our findings in utilizing KA to evoke seizures, RGB has revealed anticonvulsant properties in other adult seizure models such as electroshock, systemic PTZ, and amygdala kindling.45,46 Anticonvulsant effects of RGB were also reported at younger ages in development following rapid kindling epileptogenesis22 or after PTZ-induced seizures.24 However, we observed biphasic effects in adults: Lower doses were efficacious against behavioral and electrographic seizures, whereas higher doses exacerbated the acute epileptic syndrome and resulted in extreme ataxia. Partial anticonvulsant effects on KA-induced seizures may be related to the pharmacodynamic properties of KA on postsynaptic KA receptors richly expressed on amygdala and CA3 neurons.47–52 For example, direct application of low nanomolar concentrations of KA to hippocampal slices evokes bursting responses that persist for several hours after washout suggesting that a long-lasting modification of CA3 neuronal properties occurs. The mechanism of these effects are not due to blockade of D-aspartate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors but rather by blocking synaptic transmission (e.g. with tetrodotoxin).48 Similar results were observed by this group when high K+ concentrations were applied, suggesting that high doses of RGB, which further open K+ channels, may act synergistically with KA-induced spontaneous bursting events to ultimately induce additive effects that exacerbate the hippocampal burst activity associated with seizure activity. Ataxic effects may also be due to multifarious pathophysiological modifications associated with KA-induced status epilepticus.

Biphasic effects (inhibition vs. excitation of epileptiform discharges) of RGB co-treatment with KA via intrahippocampal microinjection provide further evidence that the pharmacodynamic properties of KA play a role in the dual effects of RGB. Accordingly, RGB was shown to diminish both burst frequency and number of action potentials elicited by long depolarizing currents in ex-vivo entorhinal/hippocampal (mEC-HC) brain slices prepared from control and KA-treated rats. This indicates that there is a threshold for the attenuating effects, which may in part be due to dampened post-ictal discharges of the entorhinal cortex.53 Moreover, RGB reduces striatal and cortical excitability associated with psychostimulant-induced locomotor activity, which is presumed to be due to reduced dopaminergic and enhanced GABAergic neurotransmission.54 In contrast, the severe ataxia and tongue protrusion observed after KA and 5 mg/kg of RGB are likely due to RGB’s overactivation of Kv3 K+ channels. These channels regulate coupling of Na+ and Ca2+ spike-dependent Purkinje cell burst output and are highly expressed within the cerebellar vermis.55 Over-activation of brain stem nuclei such as the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMV) expressing calcium-activated K+ channels56 or the nucleus solitarius expressing presynaptic K+ channels57 may contribute to the gustatory effects.

Following the FDA safety alert from April 2013, the vast majority of patients worldwide have been taken off RGB because it caused discoloration to the skin and retinal pigment epithelium to a percentage of epilepsy cases.58 In a recent cohort study in the UK, RGB was reported to have low antiepileptic efficacy and lower long-term retention rate relative to other secondary antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).59 However, additional cohort RGB studies show a significant percent reduction in 28-day seizure rate assessment with only modest side effects that do not significantly differ from side effects produced by other AEDs, supporting its potential for future clinical use.60,61 The concept of dosage adjustment in the clinic is not novel; similar findings were discovered for the off-label use of Depakote (valproic acid), an anticonvulsant for mood disorders.42 Therefore, it is certainly plausible that a similar model may be applicable to the use of RGB, and further investigation is warranted. Our findings suggest that the side effect profile, in addition to the therapeutic efficacy, is dose-dependent. It is plausible that the side effect profile of RGB may disappear once the optimum therapeutic regimen is established. In experimental epilepsy models in adult rats, second generation AEDs have also been relatively ineffective at blocking seizures; however, despite poor seizure control, some do afford neuroprotection (e.g. valproate [VPA] and lamotrigine [LTG]).62,63 For example, LTG (3,5-diamino-6-2, 3-dichlorophenyl-1, 2, 4-triazine) an L-type calcium ion and voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker, attenuates brain damage after ischemia,63 3-nitropropionic acid toxicity,64 and KA-induced status epilepticus.4,62 Although neuroprotection by VPA has been documented in vitro, it was ineffective in a rat ischemic model and did not attenuate hippocampal degeneration caused by 4-aminopyridine in vivo.65 Furthermore, when VPA was administered chronically, side effects including nonspecific neuronal lesions and nerve cell loss were demonstrated.66 Topiramate (TPM) treatment showed lack of neurotoxic side effects at clinical doses, but a significant amount of apoptosis was observed at higher doses.67 In contrast, phenytoin (PHT) and VPA can cause apoptotic neurodegeneration in development.68 Similarly, concentration-dependent effects have been observed with carbamazepine (CBZ) whereby monoaminergic and serotonergic systems are affected in mature animals.69 In contrast, treatment with RGB or other Kv7 channel modulators such as BMS-204352 have positive anxiolytic effects without affecting the mobile activity levels in normotensive mice.70 In a companion study, we found that chronic treatment of RGB for 2–3 weeks (2–5 mg/kg daily) beginning 24 hr following the acute KA-induced episode was safe, well tolerated, did not produce neurotoxicity, and quickly calmed the animals (rats) from post-seizure-induced hyperactivity and anxiety.35 The present study showed the number of healthy appearing cells observed after 3 or 28 days following KA or RGB+KA was similar indicating that the injured neurons drop out and cell loss after the insult is complete by 3 days in non-resistant animals, consistent with our original observation.29 RGB treated animals that were resistant to seizures exhibited minimal injury indicating that RGB was neuroprotective only if seizures were significantly attenuated. Accordingly, it was illustrated that concomitant use of RGB and VPA exert supra-additive synergistic effects and can prevent or attenuate temporal lobe seizures as well as absence seizures, as seen in a 59 year-old patient suffering from pharmaco-resistance over her life-time.71,72 In addition, amygdala-kindled rats that are resistant to LTG and CBZ responded well to RGB, further indicating its clinical potential for pharmacoresistant patients.73 While RGB dosing is initially based upon patient presentation in the clinical setting, it seems that further scrutiny is necessary to fine-tune and determine the appropriate dose to ensure maximal therapeutic benefit. Thus, slow titration, pulsing lower doses of RGB, or lower efficacious doses combined with lower doses of VPA or other AED candidates all could be a clinical option to reduce adverse side effects for drug resistant seizures and perhaps anxiety disorders.

Previously, we reported that GluR1 subunit expression, the major fast synaptic central receptor, was stable in adult rats at both RNA and protein levels at acute times after the KA-induced insult (e.g. 12–24 hr), which was reconfirmed in this study.28–29 Herein, irrespective of treatment, animals with stage 5–6 seizures exhibited loss of GluR1 subunit expression which was commiserate with characteristic hippocampal injury at the delayed times points (3 and 28 days). This is consistent with GluR1 depletions reported in juvenile rats of prepubescent age at 3 days after KA-Induced seizures.31 The percent decrease of GluR1 expression relative to controls showed the CA1 had the largest reduction overall, which was likely due to the wide-spread injury still prominent to this area at the age of our animals, approximately P60. The persistent loss of GluR1 expression within surviving populations of CA3 neurons at 3 or 28 days after continued RGB treatment suggests RGB may eventually cause an indirect reduction in fast synaptic transmission mediated by AMPA receptors, which may benefit certain patients with epilepsy. In keeping with this, within the DG, GluR1 and GluR2 subunit levels decreased in prepubescent rats 3 days after KA-induced status epilepticus.31 In this study, we show that GluR1 subunit expression in the GCL was specifically decreased after KA+RGB at 3 days and also after 2 weeks of daily RGB treatment in the absence of KA seizures. These data suggest (i) that GluR1 expression varies as a function of seizure severity, age, and time after the insult and (ii) loss of GluR1 among surviving pyramidal and granule cells may contribute to a reduction in fast synaptic transmission that may further dampen excitability with continued RGB treatment. The indirect inhibition of GluR1 subunit expression by RGB exposure may be additive or synergistic with KA-induced seizures. In conclusion, the full mechanisms of RGB are still under investigation and polytherapeutic treatment may still be considered as an option in future trials for drug-resistant epilepsy patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the GlaxoSmithKline: GW58292-11653. We thank the Cell Biology & Anatomy Department for laboratory space and provision of students.

References

- 1.Ciliberto MA, Weisenberg JLZ, Wong M. Clinical utility, safety, and tolerability of ezogabine (retigabine) in the treatment of epilepsy. Drug Health Patient Saf. 2012;4:81–6. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S28814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourgeois BF. Antiepileptic drugs, learning, and behavior in childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39:913–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaitatzis A, Sander JW. The long-term safety of antiepileptic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:435–55. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halonen T, Nissinen J, Pitkanen A. Effect of lamotrigine treatment on status epilepticus-induced neuronal damage and memory impairment in rat. Epilepsy Res. 2001;46:205–23. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Yang Y, Silveira DC, et al. Consequences of recurrent seizures during early brain development. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1443–54. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patsalos PN. Drug interactions with the newer antiepileptic drugs (AEDSs) – Part 2: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between AEDs and drugs used to treat non-epilepsy disorders. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52:1045–61. doi: 10.1007/s40262-013-0088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter RJ, Burdette DE, Gil-Nagel A. Retigabine as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial-onset seizures: integrated analysis of three pivotal controlled trials. Epilepsy Res. 2012;101:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter RJ, Partiot A, Sachdeo R, et al. Randomized, multicenter, dose-ranging trial of retigabine for partial-onset seizures. Neurology. 2007;68:1197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259034.45049.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tompson DJ, Crean CS, Reeve R, et al. Efficacy and tolerability exposure-response relationship of retigabine (ezogabine) immediate-release tablets in patients with partial-onset seizures. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1174–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deckers CL, Czuczwar SJ, Hekster YA, et al. Selection of antiepileptic drug polytherapy based on mechanisms of action: the evidence reviewed. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1364–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mecklenburg L, Schraermeyer U. An overview on the toxic morphological changes in the retinal pigment epithelium after systemic compound administration. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:252–67. doi: 10.1080/01926230601178199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deeks ED. Retigabine (ezogabine): in partial-onset seizures in adults with epilepsy. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:887–900. doi: 10.2165/11205950-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fattore C, Perucca E. Novel medications for epilepsy. Drugs. 2011;71:2151–78. doi: 10.2165/11594640-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisenberg JL, Wong M. Profile of ezogabine (retigabine) and its potential as an adjunctive treatment for patients with partial-onset seizures. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:409–14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S14208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garin Shkolnik T, Feuerman H, Didkovsky E, et al. Blue-Gray Mucocutaneous Discoloration: A New Adverse Effect of Ezogabine. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:984–9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stafstrom CE, Grippon S, Kirkpatrick P. Ezogabine (retigabine) Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:729–30. doi: 10.1038/nrd3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Large CH, Sokal DM, Nehlig A, et al. The spectrum of anticonvulsant efficacy of retigabine (ezogabine) in animal models: Implications for clinical use. Epilepsia. 2012;53:425–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rundfeldt C, Netzer R. The novel anticonvulsant retigabine activates M-currents in Chinese hamster ovary-cells tranfected with human KCNQ2/3 subunits. Neurosci Lett. 2000;282:73–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunthorpe MJ, Large CH, Sankar R. The mechanism of action of retigabine (ezogabine), a first-in-class K+ channel opener for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:412–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orhan G, Wuttke TV, Nies AT, et al. Retigabine/Ezogabine, a KCNQ/K(V)7 channel opener: pharmacological and clinical data. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:1807–16. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.706278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Sarro G, Di Paola E, Conte G, et al. Influence of retigabine on the anticonvulsant activity of some antiepileptic drugs against audiogenic seizures in DBA/2 mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;363:330–6. doi: 10.1007/s002100000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forcelli PA, Janssen MJ, Vicini S, Gale K. Neonatal exposure to anti-epileptic drugs disrupts striatal synaptic development. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:363–72. doi: 10.1002/ana.23600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otto JF, Yang Y, Frankel WN, et al. Mice carrying the szt1 mutation exhibit increased seizure susceptibility and altered sensitivity to compounds acting at the m-channel. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1009–16. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.65703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazarati A, Wu J, Shin D, Kwon YS, Sankar R. Antiepileptogenic and antiictogenic effects of retigabine under conditions of rapid kindling: an ontogenic study. Epilepsia. 2008;49:17777–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith MD, Adams AC, Saunders GW, et al. Phenytoin- and carbamazepine-resistant spontaneous bursting in rat entorhinal cortex is blocked by retigabine in vitro. Epilepsy Res. 2007;74:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulter J, Hollmann M, O’Shea-Greenfield A, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of glutamate receptor subunit genes. Science. 1990;249:1033–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2168579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keinänen K, Wisden W, Sommer B, et al. A family of AMPA-selective glutamate receptors. Science. 1990;249:556–60. doi: 10.1126/science.2166337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman LK. Calcium: a role for neuroprotection and sustained adaptation. Molecular Interventions. 2006;6:315–29. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.6.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman LK, Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Sperber EF, et al. Kainate-induced status epilepticus alters glutamate and GABAA receptor gene expression in adult rat hippocampus: an in situ hybridization study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2697–707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02697.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Friedman LK, Kaur J, Keesey R. Perinatal seizures preferentially protect CA1 neurons from seizure-induced damage in prepubescent rats. Seizure: Eur J of Epilepsy. 2006;15:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman LK, Avallone J, Magrys B, Liu H. Age-dependent effects of seizures on AMPA receptors. Dev Neurosci. 2007;29:427–37. doi: 10.1159/000100078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paxinos G, Watson CR, Emson PC. AChE-stained horizontal sections of the rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Neurosci Methods. 1980;3:129–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickel B, Szelenyi I. Comparison of changes in the EEG of freely moving rats induced by enciprazine, buspirone and diazepam. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:799–803. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116:201–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slomko AM, Naseer Z, Ali SS, et al. Retigabine calms seizure-induced behavior following status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman LK. Selective reduction of GluR2 protein in adult hippocampal CA3 neurons following status epilepticus but prior to cell loss. Hippocampus. 1998;8:511–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:5<511::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, et al. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science. 1998;282:1890–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neuron. Nature. 1980;283:673–6. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halliwell JV, Adams PR. Voltage-clamp analysis of muscarinic excitation in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1982;250:71–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vervaeke K, Gu N, Agdestein C, et al. Kv7/KCNQ/M-channels in rat glutamatergic hippocampal axons and their role in regulation of excitability and transmitter release. J Physiol. 2006;29:105–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yue C, Yaari Y. KCNQ/M channels control spike after depolarization and burst generation in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4614–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0765-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenfield LJ., Jr Molecular mechanisms of antiseizure drug activity at GABAA receptors. Seizure. 2013;22:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rundfeldt C. The new anticonvulsant retigabine (D-23129) acts as an opener of K+ channels in neuronal cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;336:243–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Rijn CM, Willems-van Bree E. Synergy between retigabine and GABA in modulating the convulsant site of the GABAA receptor complex. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;464:95–100. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rostock A, Tober C, Rundfeldt C. D-23129: a new anticonvulsant with a broad-spectrum activity in animal models of epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1996;23:L211–23. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tober C, Rostock A, Rundfeldt C, Bartsch R. D-23129: a potent anti-convulsant in the amygdala-kindling model of complex partial seizures. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;30:163–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ben-Ari Y, Cossart R. Kainate, a double agent that generates seizures: two decades of progress. Trends Neuroscience. 2000;23:580–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ben-Ari Y, Gho M. Long-lasting modification of the synaptic properties of rat CA3 hippocampal neurones induced by kainic acid. J Physiol. 1988;404:365–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H, Rogawski MA. GluR5 kainate receptor mediated synaptic transmission in the basolateral amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinheiro PS, Lanore F, Veran J, et al. Selective block of postsynaptic kainate receptors reveals their function at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:323–31. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Represa A, Ben-Ari Y. Effects of colchicine treatment on the cholinergic septohippocampal system. EXS. 1989;57:288–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9138-7_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Werner P, Voigt M, Keinänen K, et al. Cloning of a putative high-affinity kainate receptor expressed predominantly in hippocampal CA3 cells. Nature. 1991;351:742–4. doi: 10.1038/351742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hetka R, Rundfeldt C, Heinemann U, Schmitz D. Retigabine strongly reduces repetitive firing in rat entorhinal cortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;386:165–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hansen HH, Andreasen JT, Weikop P, Mirza N, Scheel-Krüger J, Mikkelsen JD. The neuronal KCNQ channel opener retigabine inhibits locomotor activity and reduces forebrain excitatory responses to the psychostimulants cocaine, methylphenidate and phencyclidine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;570:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKay BE, Turner RW. Kv3 K+ channels enable burst output in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:729–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sah P. Role of calcium influx and buffering in the kinetics of Ca(2+)-activated K+ current in rat vagal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:2237–47. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haji A, Ohi Y. Inhibition of spontaneous excitatory transmission induced by codeine is independent on presynaptic K+ channels and novel voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the guinea-pig nucleus tractus solitarius. Neuroscience. 2010;169:1168–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ascaso FJ, Mauri JA, Mateo J, et al. Retigabine-induced retinal dystrophy: First reported case. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2013;91:s252. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wehner T, Chinnasami S, Novy, Bell GS, Duncan JS, Sander JW. Long term retention of retigabine in a cohort of people with drug resistant epilepsy. Seizure. 2014;23:878–81. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perucca E, Meador KJ. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2005;18:30–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sachdeo R, Partiot A, Biton V, Rosenfeld WE, Nohria V, Tompson D. A novel design for a dose finding, safety, and drug interaction study of an antiepileptic drug (retigabine) in early clinical development. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;52:509–18. doi: 10.5414/CP202081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maj R, Fariello R, Ukmar G, Varasi M, Pevarello P, McArthur RA. PNU-151774E protects against kainate-induced status epilepticus and hippocampal lesions in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;359:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trojnar MK, Malek R, Chroscinska M, Nowak S, Błaszczyk B, Czuczwar SJ. Neuroprotective effects of antiepileptic drugs. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002;54:557–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee WT, Shen YZ, Chang C. Neuroprotective effect of lamotrigine and MK-801 on rat brain lesions induced by 3-nitropropionic acid: evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging and in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuroscience. 2000;95:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie X, Hagan RM. Cellular and molecular actions of lamotrigine: Possible mechanisms of efficacy in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;38:119–30. doi: 10.1159/000026527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sobaniec-Lotowska M, Sobaniec W, Kulak W. Rat liver pathomorphology during prolonged sodium valproate administration. Materi Med Pol. 1993;25:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glier C, Dzietko M, Bittigau P, Jarosz B, Korobowicz E, Ikonomidou C. Therapeutic doses of topiramate are not toxic to the developing rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Genz K, et al. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15089–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222550499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okada M, Hirano T, Mizuno K, et al. Effects of carbamazepine on hippocampal serotonergic system. Epilepsy Res. 1998;31:187–98. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Korsgaard MP, Hartz BP, Brown WD, Ahring PK, Strøbaek D, Mirza NR. Anxiolytic effects of Maxipost (BMS-204352) and retigabine via activation of neuronal Kv7 channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:282–92. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luszczki JJ, Wu JZ, Raszewski G, Czuczwar SJ. Isobolographic characterization of interactions of retigabine with carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate in the mouse maximal electroshock-induced seizure model. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:163–79. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vossler DG, Yilmaz U. Ezogabine treatment of childhood absence epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2014;16:121–4. doi: 10.1684/epd.2014.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Srivastava AK, Alex AB, Wilcox KS, White HS. Rapid loss of efficacy to the antiseizure drugs lamotrigine and carbamazepine: a novel experimental model of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1186–94. doi: 10.1111/epi.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]