Abstract

AIM: To study the epidemiology of gastric malignancies in Jordan as a model for Middle East countries where such data is scarce.

METHODS: Pertinent epidemiological and clinicopathological data for 201 patients with gastric malignancy in north of Jordan between 1991 and 2001 were analyzed.

RESULTS: Male: female ratio was 1.8:1. The mean age was 61.2 years, and 8.5% of the patients were younger than 40 years of age. The overall age- adjusted incidence was 5.82/100 000 population/year. The age specific incidence for males raised from 1.48 in those aged 30-39 years to 72.4 in those aged 70-79 years. Adenocarcinomas, gastric lymphomas, malignant stromal tumors, and carcinoids were found in 87.5%, 8%, 2.5%, and 2% respectively. There was an average of 10.1-month delay between the initial symptoms and the diagnosis. Only 82 patients underwent “curative” gastrectomy. Among adenocarcinoma groups, Lauren intestinal type was the commonest (72.2%) and the distal third was the most common localization (48.9%). The mean follow up for patients with gastric adenocarcinoma was 25.1 mo (range 1 mo -132 mo) . The 5-year survival rates for stages I (n = 15), II (n = 41), III (n = 59), and IV (n = 53) were 67.3%, 41.3%, 5.7%, and 0% respectively (P = 0.0001). The overall 5 year survival was 21.1%.

CONCLUSION: Despite low incidence, some epidemiological features of gastric cancer in Jordan mimic those of high-risk areas. Patients are detected and treated after a relatively long delay. No justification in favor of a possible gastric cancer screening effort in Jordan is supported by our study; rather, the need of an earlier diagnosis and subsequent better care.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most prevalent cancers and, today, is the second cause of cancer death worldwide[1,2]. The pattern and incidence of GC vary widely between different parts of the world. Costa Rica and Japan have the first and second highest rates in the world with a death rate of 77.5 and 50.5 /100 000 population, respectively[2,3]. In the United States 12 100 deaths from GC were expected during 2003 with a death rate of 6.8/100 000, and it was estimated that 224 00 (13 400 in men) new cases of GC were diagnosed in the same year[4]. The risk of developing GC was relatively lower in the Middle East and North Africa compared to those of western countries[1,5].

The epidemiology of GC has been widely studied in the Western world as well as in Japan[6-12]. However, only few scattered reports from the developing world have been published[13-17]. There is a lack of good descriptive data on GC from the Middle East countries, where both cancer registration and prevalence of risk factors are relatively unknown. Because of the decreasing trend that took place in the Western world as a result of possibly, socio-economic development and its consequences, it is important to gain an insight into what is happening in other parts of the world such as in the Middle East. This prompted us to report on the epidemiological and clinicopathological features of gastric malignancy in Jordan in comparison to other countries whenever possible. This could assist in the better understanding of the important risk factors, which contribute to the development of GC. This will also give a clue about whether or not screening programs are needed in our region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This is a retrospective study of gastric malignancy in the north of Jordan over an eleven-year period (Jan 1991 to Dec 2001). The population of Irbid province (north of Jordan) as determined in the last official census conducted in Jordan in 1994 was 745 774 out of which 385 264 (51.66%) were males. Fifty percent of the Jordanian population are below the age of 16 years[18]. A total of 76% of the population live in cities and towns.

Initial data were obtained from the computer database at the Department of Pathology at Jordan University of Science and Technology. This is the only pathology center serving the area. Histologically confirmed primary gastric malignancy was found in 201 patients, including 176 patients with adenocarcinoma, 16 patients with primary gastric lymphoma (PGL), 5 patients with malignant gastric stromal tumors, and 4 patients with gastric carcinoids. Further information was obtained from the medical records of these patients at Princess Basma Teaching Hospital and Prince Rashed Teaching Hospital, the only two tertiary centers in Northern Jordan. All available endoscopy reports were reviewed. Patients and/or family members were contacted whenever possible.

A single pathologist reviewed all the histological slides. Gastric adenocarcinoma was classified into intestinal (IT), diffuse (DT), or mixed types according to the histological criteria of Lauren[19]. The site of the tumor was assessed pathologically in the resected specimens and endoscopically in the remaining cases, and was defined as that part of the stomach harboring the bulk of the tumor. Tumor staging in each patient was based on clinical information, preoperative radiological investigations, operative findings, and pathological examination. The staging was made in accordance with the TNM system endorsed by the Union Internationale Contre Le Cancer (UICC)[20].

Vital status of patients was ascertained from death certificates or from families who were contacted.

All deaths within 30 d of surgery were considered surgical mortality. The incidence rates were adjusted to the world population. Our hospital based incidence data were matched with the Jordanian National Cancer Registry (JNCR) data only for the period 1996-2001, since the Registry was established in 1996. The survival rate was analyzed for each stage by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the survival curves were compared by the log-rank test using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software Program (SPSS®, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

During the study period 201 patients with primary gastric malignancy were identified, 128 (63.7%) patients were males with a male: female ratio of 1.8:1.

Sixty-five percent of the patients (131/202) were diagnosed during the second half of the study period. Analyses of the data from the JNCR, which was established in 1996, showed that all the 131 study patients diagnosed with gastric malignancy between 1st January 1996 and 31st December 2001 appeared in the registry and there were no additional patients from northern Jordan in the registry not identified by our study.

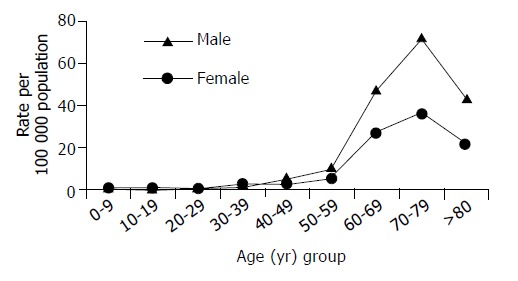

The overall age-adjusted incidence (world population) was 5.82/100 000 per year. Table 1 shows the age specific incidence rate (ASIR) per 100 000 population by gender. The peak incidence was in the age group 60-69 years (39.8%), followed by the age group 70-79 (22.9%). Approximately 8.5% of the patients were younger than 40 years of age. The mean age for the whole group was 61.2 years (SD ± 12.3, range 24-91 years).

Table 1.

Age specific incidence rate per 100 000 population/year by age and gender

| Age (yr) group |

Male |

Female |

||||

| Population | No. of cancers1 | ASIR2 | Population | No. of cancers1 | ASIR2 | |

| 0-9 | 113 142 | 0 | 0 | 106 465 | 0 | 0 |

| 10-19 | 092 899 | 0 | 0 | 087 629 | 0 | 0 |

| 20-29 | 076 938 | 0 | 0 | 071 445 | 1 | 0.13 |

| 30-39 | 043 068 | 7 | 1.48 | 038 967 | 9 | 2.1 |

| 40-49 | 024 175 | 11 | 4.14 | 023 480 | 6 | 2.32 |

| 50-59 | 019 763 | 21 | 9.66 | 017 526 | 9 | 4.67 |

| 60-69 | 010 157 | 53 | 47.44 | 009 009 | 27 | 27.25 |

| 70-79 | 003 641 | 29 | 72.4 | 004 264 | 17 | 36.24 |

| ≥ 8 0 | 001 481 | 7 | 43 | 001 725 | 4 | 21.08 |

| Total | 385 264 | 128 | 3.02 | 360 510 | 73 | 1.84 |

Number of cancers during the 11-year study.

Age specific incidence rate per 100 000 population/year.

Presenting features for our patients are summarized in Table 2. Acute presentation was seen in 59 (29.4%) patients; 37 patients (18.4%) presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, 17 (8.5%) with gastric outlet obstruction, and in the remaining 5 (2.5%) patients perforation was the mode of presentation.

Table 2.

Presenting features of patients with gastric malig-nancy

| Number of patients | % | |

| Abdominal pain | 144 | 71.6 |

| Weight loss and/or anemia | 130 | 64.7 |

| Dyspepsia | 98 | 48.8 |

| Nausea, vomiting | 96 | 47.8 |

| Abdominal mass | 62 | 30.8 |

| Anorexia | 58 | 28.9 |

| Dysphagia | 44 | 21.9 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 37 | 18.4 |

| Obstruction | 17 | 8.5 |

| Perforation | 5 | 2.5 |

There was an average of 10.1-month delay (range 2 mo-17 mo) between the initial symptoms and the diagnosis. In 119 patients this was a result of reluctance in seeking medical advice and/or delay in referring patients for endoscopy. However, in five patients the delay was caused by a false negative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Table 3 shows the distribution of the different histological types according to age and sex. The histologic subtypes of the 82 patients who had gastrectomy were correctly diagnosed in pregastrectomy endoscopic biopsies except in 2 cases, which were diagnosed as IT adenocarcinoma and turned out to be of the DT in subsequent examinations of the resected specimens. Pathological examination of the 65 resected IT and mixed adenocarcinomas revealed that 51 of the cancers were moderately differentiated, 10 were poorly differentiated and four were well differentiated.

Table 3.

Histopathological distribution of gastric malignancies according to age and sex (%)

| Histopathologic diagnosis |

Age (yr) |

Sex |

Total | ||

| Mean | Range | Male | Female | ||

| Intestinal type adenocarcinoma | 62.7 | 35-91 | 90(70.9) | 37(29.1) | 127(63.2) |

| Diffuse type adenocarcinoma | 51.9 | 24-75 | 9(31) | 20(69) | 29(14.4) |

| Mixed type adenocarcinoma | 64.3 | 51-72 | 11(57.9) | 8(42.1) | 19(9.5) |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 82 | 82 | 1 | - | 1(0.5) |

| Primary gastric lymphoma | 57.9 | 41-82 | 12(75) | 4(25) | 16(8) |

| Carcinoid | 66 | 41-81 | 2(50) | 2(50) | 4(2) |

| Malignant stromal tumors | 69.4 | 43-84 | 3(60) | 2(40) | 5(2.5) |

| Total | 61.2 | 24-91 | 128(63.7) | 73(36.3) | 201(100) |

Table 4 shows the distribution of various histologic types of gastric adenocarcinoma according to the sites affected.

Table 4.

Distribution of gastric adenocarcinoma according to site (%)

| Histopathological type | Proximal third | Middle third | Distal third | Entire stomach | Total |

| Intestinal type adenocarcinoma | 22(17.3) | 30(23.6) | 70(55.1) | 5(3.9) | 127 |

| Diffuse type adenocarcinoma | 6(20.7) | 7(24.1) | 7(24.1) | 9(31) | 29 |

| Mixed type adenocarcinoma | 3(15.8) | 5(26.3) | 8(42.1) | 3(15.8) | 19 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 31(17.6) | 42(23.9) | 86(48.9) | 17(9.7) | 176 |

For gastric adenocarcinoma, using the TNM staging, 15 patients had stage I, 41 patients had stage II, 59 patients had stage III, and 53 patients had stage IV disease. In the remaining 8 patients, the stage could not be determined due to insufficient data (stage X).

Gastrectomy was performed for 82 patients (D1 in 63 and D2 in 19 patients) . Palliative resection or bypass procedures were done for 95 patients, while 3 patients with PGL had chemotherapy only. The remaining 21 patients were too frail to be treated. No patients had D3 gastrectomy. None of the patients with adenocarcinoma was given adjuvant therapy. Postoperative morbidity occurred in 25.4%(45/177) of the patients. Eight patients died during the postoperative period giving a surgical mortality of 4.5%(8/177).

For the 176 patients with adenocarcinoma, the mean follow up until December 2002 was 25.1 mo (range 1-132 mo). At that time, vital status was available for 163 patients (92.6%). The remaining 13 patients (mean age 59.6 years; 11 males and 2 females) were lost to follow up at a mean of 28.2 mo (range 7-86 mo). The stages of the disease for these 13 patients were I, II, III, IV, and X in 1, 2, 4, 4, and 2 patients respectively.

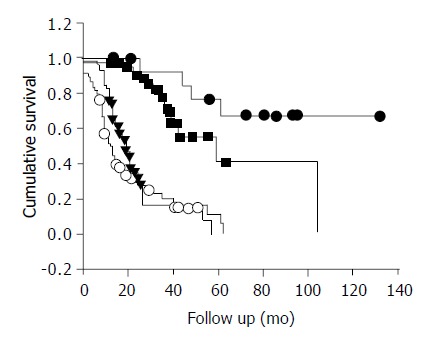

Survival analysis included the 8 early postoperative deaths and the later non-cancer deaths. The median survival for stages II, III, and both stages IV and X was 59, 19, and 13 mo respectively. Figure 1 demonstrates the survival curves for stages I -IV using Kaplan-Meier method. The 5 year survival rates for stages I, II, III, and IV were 67.3%, 41.3%, 5.7%, and 0% respectively (P = 0.0001). The overall 5 year survival was 21.1%.

Figure 1.

Survival rate of gastric adenocarcinoma patients ac-cording to stage using Kaplan-Meier analysis. (●) Stage I; n = 15, (■) Stage II; n = 41, (▼) Stage III; n = 59, (○) Stage IV and X; n = 61.

DISCUSSION

There was consistency between our study and the data of the JNCR. The incidence was calculated and corrected for age in relation to the world population. The age-adjusted incidence of gastric malignancy in this study was 5.82/100 000 per year, which was significantly lower than those of developed countries but rather similar to most other Middle East countries[1,2]. However, this incidence would rise sharply when the ASIR is calculated because of the specific pyramidal age distribution of our population where approximately 50% of our population are below the age of 16 years (1994 census) . The ASIR for males per 100000 population raised from 1.48 in those aged 30-39 years to 72.4 in those aged 70-79 years (Figure 2). Similarly, figures from the JNCR showed that during 1997, the ASIR raised sharply from 3.3 to 108 for the same gender and age groups[18]. During the same year GC was the eighth commonest cancer, representing 4% of all cancer cases, and it accounted for 22% of all primary gastrointestinal tract cancers.

Figure 2.

Age specific incidence rate per 100 000 population/year by gender.

It is well known that the incidence of GC is decreasing globally. The apparent increase in diagnosing GC during the second half of the study period most likely reflects a better diagnostic yield after the relatively recent introduction of endoscopic services throughout the country rather than an actual increase in the incidence. Still the following two factors may play a role in this increasing trend. First, the rapid change in dietary habits Jordan is witnessing might constitute a risk factor. Vitamin C-rich fresh vegetables and fruits, starch, and natural unprocessed wheat products were the major constituents of Jordanian food. However, canned food, hot spices, pickles, and animal proteins are now dominating the Jordanian menu. It is known that the environmental risk factors for GC could be dietary in origin[21,22]. Second, the already high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Jordan is increasing and the exposure time is also increasing with the improvement in life expectancy among Jordanians[23,24] . It is proposed that Lauren’s IT of GC is related to chronic Helicobacter pylori infection. Among our study group IT adenocarcinoma was the commonest histological subtype (63.2%).

Most resections were done with palliative intent. The low rate of gastrectomy with “curative” intent could be explained by the high proportion of patients with advanced GC at presentation. However, we believe that surgical undertreatment might be a contributing factor. Our patients tended to present late as evidenced by the facts that there was a long interval between onset of symptoms and presentation, 29.4% presented acutely, and that only 40.8%(82/201) of them underwent D1 or D2 gastrectomy. This is not only due to insufficiency of current endoscopic services, but also due to the fact that many people in Jordan who have non-specific dyspeptic symptoms will seek the advice of non-physician personnel who will either prescribe herbal medicine for long term treatment or induce patches of second or third degree burns to the epigastric region using hot metals in order to ameliorate the deep seated pain! Subsequently some of these patients in whom the cause of dyspepsia is cancer will present to the hospital with late stage GC or one of its complications. In addition, the elderly people usually fail to make use of the available medical services due to inadequacy of primary health care in Jordan.

Some GC patterns in north of Jordan were similar to those reported from high-risk regions worldwide[3,25]. In particular, the mean age was in the seventh decade, male to female ratio was 1.8:1, IT adenocarcinoma was more common than DT (4.4:1), and distal location was more frequent than proximal one (2.5:1). Since the demographic features among Jordanians are homogenous, we believe that these trends apply to whole Jordan. In contrary, in a low-risk area, such as Kenya, the DT is the commonest subtype[26].

In our study, DT adenocarcinoma occurred in younger patients with a mean age of 51.9 years and was commoner in females with a male to female ratio of 0.45:1 (Table 3). Similar findings of diffuse tumors prevailing among young patients and women were reported from Sweden, Finland, Mexico and Taiwan[6,8,16,17], but not from neighboring Saudi Arabia[14,15].

Our survival rate for stages I and II is consistent with the rate reported in the Western literature[27,28]. However, this rate was much lower for our patients with more advanced stages probably reflecting undertreatment at our institute. After the introduction of a specialized upper gastrointestinal unit at our hospital in January 2001, we have adopted a more radical approach.

In Western countries, PGL represented only 2% to 5% of gastric malignancies[29], while it represented 8% of our series, which was similar to the 9% figure from neighboring Iraq[30], but different from the 14-22% figure reported from Saudi Arabia[14,15]. During the past three decades the site of PGL in the Middle East has changed[31]. Small intestinal involvement became less common, and gastric involvement more frequent. This varying pattern seemed to be environmental in origin[31]. Although the ratio of PGL to gastric adenocarcinoma among our patients was higher than in western series, a recent study from Jordan demonstrated that other patterns of PGL were mimicking those of the west[32]. The stomach was the commonest site of involvement, accounting for 62% of all cases[32].

Our rates for the gastric malignant stromal tumors and carcinoids are consistent with rates reported elsewhere[33]. The survival rate for these patients was not calculated due to the small number of patients.

At the end of this discussion, we would like to highlight some of the shortcomings in our study. First, the incidence figures were calculated only after histological confirmation by endoscopy or surgery. In Jordan, hospital postmortem is rarely performed because of religious or social grounds. Additionally, only half of deaths are attended by medical workers personals. This means that some patients with GC were certainly not included in the incidence calculation. The limitation to histologically confirmed cases increases specificity but lowers the sensitivity in identifying cases to be included in the incidence figures. Cases admitted to hospitals with a suspicion of GC or deceased with a diagnosis of GC but without histological confirmation were not considered in the estimation of incidence rates. Additionally as one third of our patients presented with an abdominal mass, and there was a 10-mo delay in diagnosis so the estimated incidence was lower than the real incidence because many patients did not reach the hospitals. Second, Lauren classification is known to be affected by a quite low reproducibility[34]. Specifically, mixed cases might be classified as intestinal or as diffuse type, depending on the examined tissue areas endoscopically biopsied or from the surgical specimens.

In conclusion, the incidence of GC in Jordan is low, but increases appreciably with age. This, in addition to the fact that 50% of the Jordanian population are below the age of 16 years, shows that it does not seem justified introducing a screening program. However, general practitioners should be more liberal in referring patients for endoscopy and resist the temptation to treat dyspeptic patients with anti-ulcer therapy without an endoscopy. Open access endoscopy, greater efforts in patient education and improvement of the diagnostic technical skills may raise the chance of detecting GC early. Some patterns of GC in Jordan (age, sex, tumor location, and histological type) are similar to features from high-risk areas. Although this study clearly highlights the pertinent epidemiological and clinicopathological features of gastric malignancy in Jordan, further studies are needed to evaluate the treatment outcomes.

Footnotes

Edited by Zhu LH and Xu FM

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:827–841. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:33–64, 1. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasagawa T, Solano H, Mena F. Gastric cancer in Costa Rica. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:594–595; discussion 594-595;. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Erratum: Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int. J. Cancer, 83, 18-29 (1999) Int J Cancer. 1999;83:870–873. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991210)83:6<870::aid-ijc35>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekström AM, Hansson LE, Signorello LB, Lindgren A, Bergström R, Nyrén O. Decreasing incidence of both major histologic subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma--a population-based study in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:391–396. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaneko S, Yoshimura T. Time trend analysis of gastric cancer incidence in Japan by histological types, 1975-1989. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:400–405. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurén PA, Nevalainen TJ. Epidemiology of intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma. A time-trend study in Finland with comparison between studies from high- and low-risk areas. Cancer. 1993;71:2926–2933. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10<2926::aid-cncr2820711007>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haugstvedt TK, Viste A, Eide GE, Maartmann-Moe H, Myking A, Søreide O. Is Lauren's histopathological classification of importance in patients with stomach cancer A national experience. Norwegian Stomach Cancer Trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1992;18:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stelzner S, Emmrich P. The mixed type in Laurén's classification of gastric carcinoma. Histologic description and biologic behavior. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1997;143:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leocata P, Ventura L, Giunta M, Guadagni S, Fortunato C, Discepoli S, Ventura T. [Gastric carcinoma: a histopathological study of 705 cases] Ann Ital Chir. 1998;69:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monferrer Guardiola R, Peiro Gomez AM, Galiana Gil R, Montes Rotgla A, Lillo Sanchez A, Cuevas Campos A. [Incidence of gastric cancer in the 02 health area of Castellon] An Med Interna. 1996;13:68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson O, Ersumo T, Ali A. Gastric carcinoma at Tikur Anbessa Hospital, Addis Ababa. East Afr Med J. 2000;77:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamdi J, Morad NA. Gastric cancer in southern Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 1994;14:195–197. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1994.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Mofleh IA. Gastric cancer in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy population: Prevalence and clinicopathological characteristics. Ann Saudi Med. 1992;12:548–551. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1992.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohar A, Suchil-Bernal L, Hernández-Guerrero A, Podolsky-Rapoport I, Herrera-Goepfert R, Mora-Tiscareño A, Aiello-Crocifoglio V. Intestinal type: diffuse type ratio of gastric carcinoma in a Mexican population. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1997;16:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CW, Tsay SH, Hsieh MC, Lo SS, Lui WY, P'eng FK. Clinicopathological significance of intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma in Taiwan Chinese. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:1083–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Kayed S, Hijawi B. Cancer incidence in Jordan 1997 report. National Cancer Registry. The hashemite kingdom of Jordan. Amman (HKJ), Ministry of Health. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.LAUREN P. THE TWO HISTOLOGICAL MAIN TYPES OF GASTRIC CARCINOMA: DIFFUSE AND SO-CALLED INTESTINAL-TYPE CARCINOMA. AN ATTEMPT AT A HISTO-CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermanek P, Sobin L. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 4th ed. Berlin: Springer Verlag. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngoan LT, Mizoue T, Fujino Y, Tokui N, Yoshimura T. Dietary factors and stomach cancer mortality. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:37–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palli D. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: an evaluation of available evidence. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35 Suppl 12:84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bani-Hani KE, Hammouri SM. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Northern Jordan. Endoscopy based study. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:843–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latif AH, Shami SK, Batchoun R, Murad N, Sartawi O. Helicobacter pylori: a Jordanian study. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:994–998. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.67.793.994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correa P. Clinical implications of recent developments in gastric cancer pathology and epidemiology. Semin Oncol. 1985;12:2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogutu EO, Lule GN, Okoth F, Musewe AO. Gastric carcinoma in the Kenyan African population. East Afr Med J. 1991;68:334–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis PA, Sano T. The difference in gastric cancer between Japan, USA and Europe: what are the facts what are the suggestions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40:77–94. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuchs CS, Mayer RJ. Gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:32–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hertzer NR, Hoerr SO. An interpretive review of lymphoma of the stomach. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976;143:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Bahrani Z, Al-Mondhiry H, Bakir F, Al-Saleem T, Al-Eshaiker M. Primary gastric lymphoma. Review of 32 cases from Iraq. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1982;64:234–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taleb N, Chamseddine N, Abi Gergis D, Chahine A. [Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the digestive system. General epidemiology and epidemiological data concerning 100 Lebanese cases seen between 1965 and 1991] Ann Gastroenterol Hepatol (Paris) 1994;30:283–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almasri NM, al-Abbadi M, Rewaily E, Abulkhail A, Tarawneh MS. Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas in Jordan are similar to those in Western countries. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, eds World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon IARC Press. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palli D, Bianchi S, Cipriani F, Duca P, Amorosi A, Avellini C, Russo A, Saragoni A, Todde P, Valdes E. Reproducibility of histologic classification of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 1991;63:765–768. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]