Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic allergic, immune-mediated disorder resulting in esophageal eosinophilia and dysfunction.1 There is a strong need to identify additional biomarkers for confirmation of disease and response to treatment. 2–5

Autophagy (macroautophagy) is a cellular adaptive response to physiologic stressors such as starvation and inflammation that targets dysfunctional intracellular materials for degradation via autophagic vesicles.6 The formation of autophagic vesicles involves autophagy-related (ATG) gene products. ATG dysregulation has been implicated in immune disorders such as Crohn Disease7 and ATGs may serve as disease biomarkers.8 Thus, we hypothesized that ATG expression may be altered in esophageal biopsies from active EoE patients.

Utilizing quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), we first evaluated expression of ATG3, ATG6, ATG7, ATG8 and ATG14 in a limited pediatric cohort. A full description of these methods is provided in the Methods section in this article's supplementary material. ATG6, ATG7 and ATG8 expression was higher in active EoE subjects (n=5) when compared to normal (n=5) and EoE remission subjects (n=5)(data not shown).

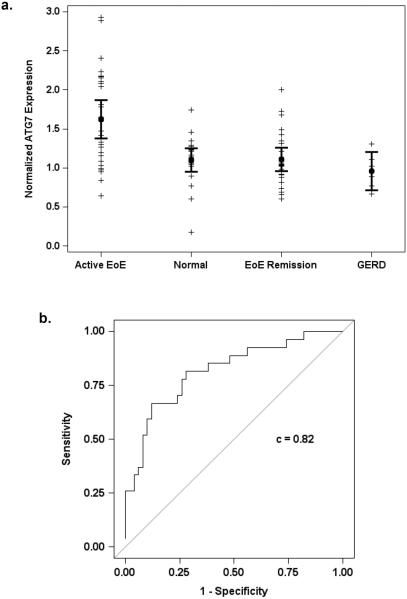

Further analysis was performed of a larger pediatric patient cohort (Table 1) including four patient groups: active EoE, EoE remission, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) and normal. ATG7 was upregulated in active EoE patients (n=27) compared to non-EoE (i.e. GERD and normal; n=26, p = 0.001) and EoE remission (n=24, p < 0.001)(Figure 1a) subjects. Logistic regression analysis of ATG7 level adjusted for age revealed an odds ratio of 12.1 (95% CI 3.0, 49.5) for active EoE. Moreover, the area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the model's predicted value was 0.82 (Figure 1b). Therefore, ATG7 may serve as a valuable tissue biomarker distinguishing active EoE from remission and non-EoE states. Using 1.6 as an optimal cut point of the ATG7 expression level, patients can be classified as active EoE with 48.1% sensitivity and 88% specificity and positive and negative predictive values of 68% and 76%, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). While not a sensitive marker for active EoE, the remarkable specificity of ATG7 highlights it's potential as a valuable diagnostic measure in conjunction with standard histopathological evaluation, particularly in cases with ambiguous eosinophil counts and or in children who are not on PPI at the time of endoscopy. Biomarker potential was further supported by a nearly significant (p=0.06) (data not shown) repeated measures analysis of ATG7 expression in a small cohort of EoE patients who transitioned from active EoE to EoE Remission or vice versa (n=18).

Table 1.

Clinical Data Summary including disease status with percent of male subjects per group as well as age in years (y) and eosinophil count per high power field (hpf) represented by median and interquartile range (IQR)

| Status | Age (y) range, Median (IQR) | Eosinophil count/hpf, Median (IQR) | Male, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n=20) | 7.33 (4.6 – 15.5) | 0.00 (0.0 – 0.0) | 19 (95%) |

| GERD (n=6) | 4.33 (1.8 – 7.7) | 0.00 (0.0 – 0.0) | 4 (67%) |

| EoE Remission (n=24) | 7.50 (4.9 – 9.4) | 1.00 (0.0 – 3.5) | 20 (83%) |

| Active EoE (n=27) | 11.42 (5.7 – 13.7) | 35.00 (25.0 – 50.0) | 22 (81 %) |

Figure 1. ATG7 may serve as novel tissue biomarker for diagnosis of active EoE inflammation in pediatric patients.

(a) qRT-PCR was performed to evaluate ATG7 mRNA expression in esophageal biopsies. (b) ROC curve for predicted values from logistic regression analysis of ATG7 adjusted for age in active versus non-active EoE subjects.

Linear regression analysis revealed only a modest positive correlation between ATG7 and eosinophilic infiltrate (r2 = 0.22)(data not shown), suggesting that ATG7 elevation may represent a specific and independent marker of active EoE. To further validate this relationship, the non-EoE group was sub-stratified into normal (n=20) and PPI-treated GERD (n=6) patients; the latter defined by a history of reflux and evidence of histologic non-EoE inflammatory changes. ATG7 expression remained significantly elevated in patients with active EoE compared to normal (p = 0.001) and GERD (p= 0.017)(Figure 1a).

In summary, we have identified ATG7 as a potential tissue biomarker distinguishing active EoE from normal, EoE remission and GERD. Since subjects in this study were PPI-treated and exhibited minimal inflammation, further study is warranted in GERD subjects prior to PPI treatment to determine if ATG7 remains specific for active EoE. If this is the case, discovery of a specific tissue biomarker for EoE will provide clarity for ambiguous cases and may allow patients to avoid the recommended 8–12 week course of high dose PPI prior to esophagogastroduodenoscopy, resulting in earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Identification of autophagy related biomarkers in EoE may also be applicable to esophageal samples obtained from less invasive disease monitoring tools such as the esophageal string test9 or cytosponge.10 Interestingly, miR-375, a microRNA that negatively regulates ATG7 expression and autophagy,11 is the most downregulated microRNA in esophageal biopsies from active EoE subjects.12 However, additional studies are required to investigate any functional relationship between microRNA, autophagy and EoE and potential autophagy-related biomarkers. Future studies will also assess ATG7 as a prognostic marker interpreted in the context of patient age, disease course and response to therapy.

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

What is known

-

1)

EoE is a chronic, allergen-mediated disorder resulting in esophageal eosinophilia and dysfunction.

-

2)

EoE diagnosis and monitoring are currently limited to endoscopy with biopsies while on high-dose PPI therapy.

-

3)

Autophagy is a cellular adaptive homeostatic mechanism with implications in other immune mediated gastrointestinal disorders such as Crohn Disease.

What is new

-

1)

ATG7 mRNA is upregulated in active EoE patients when compared to normal, EoE remission and PPI-treated GERD patients.

-

2)

ATG7 may serve as a valuable tissue biomarker of active EoE.

-

3)

Autophagy and related genes can be explored further to understand the role in EoE and for additional disease biomarkers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Valerie Teal and Amy Praestgaard at the Biostatistics Analysis Center at the Penn Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

Grant Support:This study was supported by the following NIH Grants: P01CA098101 (HN, KAW) K26RR032714 (HN), R01DK087789 (HN, MLW, JMS), K24DK100303 (GTF), K01DK103953 (KAW), F32CA174176 (KAW), K08DK106444 (ABM), F32DK100088 (ABM), T32DK007066 (JFM, KAW), NIH/NIDDK P30-DK050306 Center of Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases, The Molecular Pathology and Imaging, Molecular Biology/Gene Expression and Cell Culture Core Facilities. Additional support was provided by American Partnership For Eosinophilic Disorders Hope Award (ABM), Abbott Nutrition (MLW), Joint Penn-CHOP Center in Digestive, Liver and Pancreatic Medicine at The Perelman School of Medicine (ABM, HN), University of Pennsylvania.

Abbreviations

- ATG

Autophagy-related

- EoE

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- PPI

Proton pump inhibitor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- ROC

receiver-operating characteristic.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Experimental design (JFM, KAW, ABM, GTF, MLW, JMS, GWF, HN); experimental execution (JFM, KAW, AJB); data analysis and interpretation (JFM, KAW, ABM, GTF, GWF, MLW, JMS, HN); reagents/materials/analysis tool contributions (JFM, AJB, ABM); manuscript writing/editing (JFM, KAW, ABM, JMS, MLW, GWF, HN).

Competing Interests: none

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011 Jul;128(1):3–20. e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stucke EM, Clarridge KE, Collins MH, Henderson CJ, Martin LJ, Rothenberg ME. The Value of an Additional Review for Eosinophil Quantification in Esophageal Biopsies. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2015 Jan 28; doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014 Dec;147(6):1238–1254. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins MH. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis and eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2014 Jun;43(2):257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pentiuk S, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Rothenberg ME. Dissociation between symptoms and histological severity in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2009 Feb;48(2):152–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817f0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes & development. 2007 Nov 15;21(22):2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadwell K, Patel KK, Komatsu M, Virgin HWt, Stappenbeck TS. A common role for Atg16L1, Atg5 and Atg7 in small intestinal Paneth cells and Crohn disease. Autophagy. 2009 Feb;5(2):250–252. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanninen TT, Jayaram A, Jaffe Lifshitz S, Witkin SS. Altered autophagy induction by sera from pregnant women with pre-eclampsia: a case-control study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2014 Jul;121(8):958–964. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuta GT, Kagalwalla AF, Lee JJ, et al. The oesophageal string test: a novel, minimally invasive method measures mucosal inflammation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2013 Oct;62(10):1395–1405. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzka DA, Geno DM, Ravi A, et al. Accuracy, safety, and tolerability of tissue collection by Cytosponge vs endoscopy for evaluation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2015 Jan;13(1):77–83. e72. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Y, Yan W, He X, et al. miR-375 inhibits autophagy and reduces viability of hepatocellular carcinoma cells under hypoxic conditions. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jul;143(1):177–187. e178. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu TX, Sherrill JD, Wen T, et al. MicroRNA signature in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, reversibility with glucocorticoids, and assessment as disease biomarkers. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012 Apr;129(4):1064–1075. e1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.