Abstract

The cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is a widespread pest of many cultivated and wild plants in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. In 2013, this species was reported in Brazil, attacking various host crops in the midwestern and northeastern regions of the country and is now found countrywide. Aiming to understand the effects of different host plants on the life cycle of H. armigera, we selected seven species of host plants that mature in different seasons and are commonly grown in these regions: cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, “FM993”), corn (Zea mays, “2B587”), soybean (Glycine max, “99R01”), rattlepods (Crotalaria spectabilis), millet (Pennisetum glaucum, “ADR300”), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, “AGROMEN70G35”), and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata, “SEMPRE VERDE”). The development time of immatures, body weight, survivorship, and fecundity of H. armigera were evaluated on each host plant under laboratory conditions. The bollworms did not survive on corn, millet, or sorghum and showed very low survival rates on rattlepods. Survival rates were highest on soybean, followed by cotton and cowpea. The values for relative fitness found on soybean, cotton, cowpea, and rattlepods were 1, 0.5, 0.43, and 0.03, respectively. Survivorship, faster development time, and fecundity on soybean, cotton, and cowpea were positively correlated. Larger pupae and greater fecundity were found on soybean and cotton. The results indicated that soybean, cotton, and cowpea are the most suitable plants to support the reproduction of H. armigera in the field.

Keywords: Helicoverpa armigera, polyphagy, plant host suitability, life cycle

The cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is a polyphagous generalist pest species that occurs worldwide. It is an important insect pest on many cultivated and wild plants in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia (Fitt 1989, Zalucki et al. 1994). H. armigera can attack more than 172 plant species from 68 different families (Zalucki et al. 1986, 1994; Fitt 1989; Singh et al. 2002; Cunningham and Zalucki 2014). Because of its polyphagy, mobility as adults, and high fecundity (Fitt 1989), H. armigera has a high potential to invade and extend the areas of infestation. The species has recently invaded South and Central America (Czepak et al. 2013, Tay et al. 2013, Múrua et al. 2014, North American Plant Protection Organization 2014), although it was likely present in South America for some time before it was detected (Kriticos et al. 2015).

In Brazil, H. armigera was considered to be an A1 quarantine pest until 2012. However, in 2013, this species was reported in different host crops in the midwestern and northeastern regions of the country (Czepack et al. 2013). The estimated crop losses from H. armigera attacks in these areas are more than US$2 billion, including the direct loss of productivity and resources spent on phytosanitation products for the main Brazilian agribusiness crops (Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento [MAPA] 2014).

Agricultural practices in Brazil use mainly annual cropping systems that create a shifting mosaic of habitats that vary spatiotemporally. Despite the instability of these systems due to the annual sequence and seasonality of crop varieties, H. armigera populations can persist and expand their range using uncultivated or nontarget crops as a bridge when the main cultivated crops are scarce. The time-limited characteristics of the host plants exploited and the sequence in which target and nontarget plants become available to H. armigera populations can influence its spatiotemporal population dynamics (Kennedy and Storer 2000) and have important consequences for the population density, spread and spatial distribution pattern in the agricultural landscape (Wardhaugh et al. 1980).

To understand what plant species can be considered a true host or an alternative (poor, i.e., only marginally suitable) host, we selected seven host plants: cotton, corn, soybean, rattlepods, millet, sorghum, and cowpea. These crops are commonly cultivated in western Bahia State (one of the regions where H. armigera was first officially reported). Because they have different growing seasons, H. armigera populations could potentially exploit them in turn through the year. The development time of immatures, body weight, survivorship, and fecundity of H. armigera feeding on each plant host were evaluated in the laboratory. On the basis of the fitness results for H. armigera on these different host plants, we evaluated their suitability and potential contribution to H. armigera population sizes. Our findings can be applied to design a comprehensive IPM scheme and to help understand the rapid expansion of this polyphagous species in different areas in Brazil.

Materials and Methods

Insect Colony and Plant Sources

The seven host plants: cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, “FM993”), corn (Zea mays, “2B587”), soybean (Glycine max, “99R01”), rattlepods (Crotalaria spectabilis), millet (Pennisetum glaucum, “ADR300”), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, “AGROMEN70G35”), and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata, “SEMPRE VERDE”) were grown under field conditions at the University of São Paulo – USP/ESALQ, without pesticides.

A laboratory colony of H. armigera was established with approximately 200 individuals collected from farms in western Bahia State (12° 5′58″ S, 045° 047′54″ W) in January 2014. New individuals were frequently added to the laboratory colony to prevent a founder effect. The adult moths were reared in cages made of PVC tubes (14 by 20 cm) closed at the top with a fine-mesh net and were allowed to mate. The adult moths were provided with a 10% honey solution. The eggs were collected from the mesh net every 48 h. After hatching, the larvae were reared on artificial diet (Greene et al. 1976) at 25°C with a photoperiod of 14:10 (L:D) h. The insects tested on different host plants were reared for at least five generations on the artificial diet to prevent any influence of the host used for the source colony (i.e., preimaginal conditioning).

Development and Survivorship of Immature Stages

For each host plant treatment, we used 600 newly hatched larvae obtained from the laboratory colony. The larvae were reared in groups of 50 in Petri dishes (15 by 2 cm) until the third instar, when they were separated in individual small Petri dishes (6 by 2 cm) to prevent cannibalism. For the first larval instar reared on soybean, cotton, and cowpea, we provided leaves; after they reached the third instar, in addition to the leaves we offered pods (soybean or cowpea) or cotton bolls. For larvae reared on corn, millet, and sorghum, at the beginning of the experiment we offered leaves and reproductive structures: parts of spikelets (anthers and ovaries) of sorghum and millet, and fresh corn kernels and silk, since the first instars of H. armigera are most commonly found on these host structures in the field (Teakle and Byrne 1988, Liu et al. 2004). The leaves and other plant parts were changed each day until pupation. After the pupae were 24 h old, they were weighed and separated by sex (Butt and Cantu 1962). Individual insects were checked daily, and survival, pupal weight, and the durations of the immature stages and the pupal period were evaluated.

Adult Longevity and Reproduction

The adult moths emerging from each host-plant treatment were placed in plastic containers supplied with 10% honey solution (one pair per container). The eggs were collected from each cage every 24 h, until the females died. The adult mortality was recorded daily. The longevity and fecundity of each mating pair were determined for each host plant. Subsequently, the female moths were dissected and examined for the presence of spermatophores, to determine whether they had mated (Liu et al. 2004). The eggs were maintained in plastic containers at 25°C for 5 d, to evaluate the hatching rates. The egg viability was estimated from the total number of hatched larvae/total number of eggs laid during the entire female adult period.

Data Analyses

The effects of different host plants and the sex of individuals on the development time and pupal weight of immatures and the adult longevity of H. armigera were analyzed with two-way analysis of variance, and the means separated by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P = 0.05) using R Software (R Development Core Team 2015). Individuals that died prior to maturing and adults that died without producing viable eggs were excluded from the analyses. Survivorship and sex-ratio comparisons among individuals reared on different host plants were tested by χ2.

Results

Survivorship of Immature Stages

The survivorship of immature stages was significantly different among host plants (Table 1). Larval survival rates were lowest for instars 1–2 on all host plants. The overall survivorship was lower than 9.2%, for all host plants (Table 1). The highest survivorship was observed on soybean, followed by cotton and cowpea. The lowest survivorship was observed for larvae reared on rattlepods; only 0.34% of individuals reached the adult stage. On corn, millet, and sorghum, larval mortality was 100% (Table 1). Considering the survivorship on soybean as reference (Wsoybean = 1), the values for relative fitness (W) found on soybean, cotton, cowpea, and rattlepods were 1, 0.5, 0.43, and 0.03, respectively (Table 1). Since the larvae reared on corn, millet, and sorghum died before reaching the pupal stage, and on rattlepod only two individuals reached the adult stage (Table 1), we considered only soybean, cotton, and cowpea as host plants for analyses of development times of immatures and adult longevity.

Table 1.

Within-stage survivorship (%) of immature stages of H. armigera on different host plants

| Stage | Soybean | Cotton | Cowpea | Rattlepods | Corn | Millet | Sorghum | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st stadium | 45.3% (600) | 18.1% (600) | 22.3% (600) | 19% (600) | 3.84% (600) | 9.5% (600) | 6.67% (600) | 0 | 1 |

| 2nd stadium | 80.5% (272) | 82.7% (109) | 77.6% (134) | 38.6% (114) | 43.47% (23) | 43.85% (57) | 67.5% (40) | 393.01 | <0.001* |

| 3rd stadium | 80.4% (219) | 65.9% (91) | 55.8% (104) | 25% (44) | 30.0% (10) | 8.9% (25) | 18.52% (27) | 428.33 | <0.001* |

| 4th stadium | 75% (176) | 75% (60) | 82.7% (58) | 45.5% (11) | 0.0% (3) | 0.0% (2) | 40% (5) | 531.64 | <0.001* |

| 5th stadium | 81.8% (132) | 91.1% (45) | 91.6% (48) | 60% (5) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 50% (2) | 425.22 | <0.001* |

| Pupa | 50.9% (108) | 70.7% (41) | 56.8% (44) | 66.7% (3) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% (1) | 346.33 | <0.001* |

| Total* | 9.16% (55) | 4.8% (29) | 4.16% (25) | 0.34% (2) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 175.03 | <0.001* |

*Total represents survivorship of immature stages from first-instar larvae to pupae. Numerals in parentheses are the number of survivors in each stage.

Development of Immature Stages and Pupal Weight

The host plants significantly affected the development time of the larval stage (host plant F2,108 = 22.06, P < 0.001; sex: F1,108 = 1.27, P = 0.262; host plant by sex F2,108 = 0.072, P = 0.931). Larvae fed on soybean and cotton developed faster than those fed on cowpea (Table 2). The duration of the pupal stage was affected by the interaction effects of sex and host plant (host plant F2,108 = 79.64, P < 0.001; sex: F1,108 = 7.97, P = 0.006; host plant by sex F2,108 = 85.83, P < 0.001). Females fed on cotton showed the longest pupal stage (Table 2). The pupal period of males did not differ among host plants (Table 2). Differently from other host plants, male and female pupae of larvae reared on cowpea did not differ in the duration of that stage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Means (± SE) for development of immatures, pupa weight, adult longevity, and sex ratio of H. armigera reared on different host plants

| Duration (d) | Pupae weight (mg) | Longevity (d)* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host | Larvae | Male pupae | Female pupae | Male | Female | Male | Female | Sex ratio |

| Soybean | 20.2(±2.4)a | 13.9(±0.8)Aa | 12.9(±1.7)Ba | 256(±0.03)Aa | 241(±0.03)Ba | 20.3(±6.6)A | 15.4(±3.8)B | 0.49a |

| Cotton | 21.1(±2.7)a | 14.8(±1.6)Aa | 13.22(±0.8)Bb | 279(±0.05)Ab | 263(±0.06)Bb | 21.6(±12.1)A | 14.5(±3.6)B | 0.31a |

| Cowpea | 24.5(±3.3)b | 13.8(±1.0)Aa | 13.0(±1.2)Aa | 194(±0.02)Ac | 174(±0.02)Bc | 24.6(±6.8)A | 18.8(±8.2)B | 0.48a |

Means within columns followed by different small letters are significantly different at P < 0.05 (i.e., comparison among host plants). Means within rows followed by different capital letters are significantly different at P < 0.05 (i.e., comparison between male and female for a specific item).

*The effect of host plants on H. armigera adult longevity was not significant (F = 1.951; P = 0.151).

H. armigera pupal weight was affected by the sex of individuals and by the host plants (host plant F2,108 = 40.6, P < 0.001; sex: F1,108 = 4.66, P = 0.033) (Table 2). The interaction of host plant and sex did not significantly affect the pupal weight (F2,108 = 0.052, P = 0.949). Pupae from these emerged males were heavier than pupae from emerged females. Pupae of larvae reared on cotton were heavier than those of larvae reared on soybean and cowpea (Table 2).

Adult Emergence and Longevity

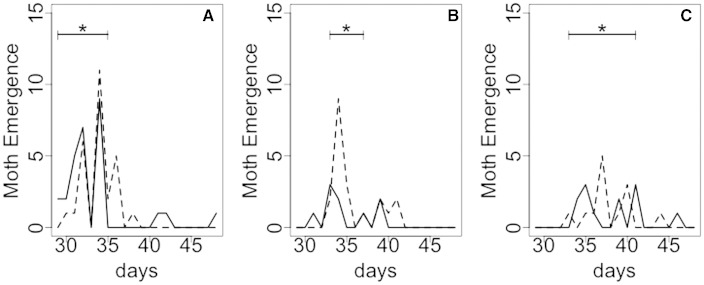

The periods corresponding to 75% of emergence for adults reared on soybean, cotton, and cowpea were on days 30–35, 33–37, and 33–41 of their life cycles, respectively (Fig. 1). The majority of moths reared on soybean emerged early, followed by moths reared on cotton and cowpea (Fig. 1). The period corresponding to 75% of emergence for moths reared on cotton was shorter (4 d) compared to moths reared on soybean (6 d) and cowpea (8 d).

Fig. 1.

Periods of H. armigera emergence of adults reared on different host plants: (A) soybean, (B) cotton, and (C) cowpea. Dashed and solid lines represent males and females, respectively. The symbol * indicates the period corresponding to 75% emergence of H. armigera reared on the different host plants.

Host plants had no effect on H. armigera adult longevity. The sex of the insects did affect adult longevity (host plant F2,61 = 2.19, P = 0.12; sex: F1,61 = 11.67, P = 0.0011); adult males lived longer than females (Table 2). The sex ratio of populations reared on soybean, cotton, and cowpea did not differ significantly (χ2 = 0.048, P = 0.97) and was close to 0.5 (Table 2).

The high mortality of the immature stages and the different periods of the male and female pupal stages did not allow us to establish enough moth couples per host-plant treatment to assess the statistical significance of the reproductive data. For moths reared on soybean, cotton, and cowpea, respectively, we obtained 20, 6, and 7 couples of H. armigera but only 14 (70%), 4 (66.7%), and 7 (100%) females bore spermatophores, and only 8, 2, and 6 females (57.2%, 50%, and 85.7%) produced viable eggs. The number of spermatophores found was not correlated with the number of eggs produced. Females from larvae reared on cotton and soybean laid more eggs (436 ± 39.59 and 433 ± 116.74, respectively) than those reared on cowpeas (274.16 ± 152.55). The viability of eggs produced by females reared on soybean, cotton, and cowpea was 62.35%, 71.10%, and 63.13%, respectively.

Discussion

The population of H. armigera tested did not survive on corn, millet, and sorghum and exhibited very low survival rates on rattlepods, indicating that these plants are poor hosts for the larvae. Despite the high mortality rates previously described for first-instar larvae (Zalucki et al. 2002), survival rates were highest on soybean, followed by cotton and cowpea, suggesting that these host plants are more suitable and allow H. armigera to complete its entire life cycle.

In polyphagous insects such as H. armigera, the temporal variation and the diversity of plant hosts raises the question of the importance of each host-plant species for the larval traits: are the larvae capable of surviving and completing development on the plant where the female laid its eggs? Studies have shown that the host oviposition preference of the adult is not always related to the performance of the offspring (Zalucki et al. 1986, Berdegué et al. 1998, Jallow and Zalucki 2003, Cunningham and Zalucki 2014). This lack of relationship stems from the wide variations in adult host choice and larval performance under different ecological conditions and selection pressures (Thompson 1988). For this reason, the recent reports of H. armigera immatures on various host plants do not necessarily mean that the larvae will reach the adult stage on those species (Kitching and Zalucki 1983, Jallow and Zalucki 2003, Cunningham and Zalucki 2014).

The reported presence of H. armigera on corn, millet, sorghum, and rattlepods in cultivated areas in Brazil may result from many factors not necessarily related to the nutritional benefits of the host plants. For instance, the presence of eggs on these host plant species can be influenced by the disproportionate frequency in which females encounter a true or an alternative (poor) host, leading the females to oviposit on a more numerous and accidental host, on which their larvae cannot feed well (Thompson 1988, Jallow and Zalucki 2003). In Brazil, most millet, sorghum, and rattlepod crops are normally planted after the main crops (soybean, cotton, and corn) are harvested. Probably, because of the absence of true hosts, the moth generations derived from the main crops then lay their eggs on these off-season crops. In this case, even a few surviving larvae could ensure the presence of some individuals, until the population increases in the next main-crop growing season (Wardhaugh et al. 1980, Jallow and Zalucki 2003).

Studies also have shown that the flowering period strongly influences the oviposition behavior of H. armigera (Wardhaugh and Room 1980, Teakle and Byrne 1988, Cunningham and Zalucki 2014) and the female moths can choose host plants on which their offspring fitness is very low (Jallow and Zalucki 2003). Therefore, the reported presence of H. armigera on corn, millet, sorghum, and rattlepod in the field may reflect their attractiveness to the adult moths and not necessarily a positive correlation between host-plant choice and larval performance.

Occurrences of H. armigera on these unsuitable hosts may also result from the choice of female moths to oviposit preferentially on hosts that ensure higher survivorship of the eggs. Older larvae could then move to more nutritionally adequate hosts (Thompson 1988, Berdegué et al. 1998, Cunningham and Zalucki 2014). A high abundance of natural enemies on some host plants may also lead females to lay their eggs on a nutritionally inferior host, to better protect their progeny (Thompson 1988). In summary, many factors must be considered before a plant species can be defined as a true host. For these reasons, reports of H. armigera in some crop systems should be evaluated with care.

Attacks of H. armigera on corn have been reported in Asia, Europe, and Australia (Maelzer and Zalucki 1999, Liu et al. 2004, Scott et al. 2006, Fefelova and Frolov 2008). However, in Brazil, the occurrence of H. armigera on corn is controversial. A recent study of H. armigera distribution in Brazil called attention to morphological similarities between H. armigera and Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Leite et al. 2014). Because these are sibling species and are capable of copulating and producing fertile offspring under laboratory conditions (Mitter et al. 1993, Cho et al. 2008), reports of them on potential host species in Brazil may be questionable.

Based on a phylogeographic analysis of natural H. armigera and H. zea populations sampled in midwestern and northeastern Brazil, Leite et al. (2014) reported a high prevalence of H. armigera on dicotyledoneous hosts (i.e., soybean, cowpea and cotton), while H. zea was prevalent on corn. On millet and sorghum, the authors reported a low occurrence of H. armigera. Our results showed that the H. armigera immatures were unable to complete their development on corn, millet, and sorghum, in agreement with the findings of Leite et al. (2014) for the distribution of H. armigera in Brazil. On the other hand, field studies in Australia have shown that sorghum and corn are potential host plants and have contributed to increases of H. armigera populations in agricultural areas (Wardhaugh et al. 1980, Maelzer and Zalucki 1999). Probably after some years, H. armigera may become more common on these crops, due to adaptation of the species to Brazilian conditions.

Regarding the analyses for soybean, cotton, and cowpea, our results showed that the components of performance (survival, development time, and fecundity) were positively correlated. On soybean and cotton, H. armigera showed high survival rates and produced heavier pupae, and although few mated females emerged in each host-plant treatment, the adults reared on these host plants were more fecund. The shorter development times and greater fecundity indicated that soybean and cotton were more suitable hosts for H. armigera than cowpea (van Lenteren and Noldus 1990).

Host plants influenced the moth emergence time. The moths originated from larvae reared on soybean emerged earliest, followed by those reared on cotton and cowpea (Fig. 1). Taking into account that for H. armigera, the mosaic of different crops in season and off-season periods can allow populations to persist year-round, differences in the length of the life cycle on each host plant can have direct consequences for the regional population dynamics (Teakle and Byrne 1988, Maelzer and Zalucki 1999).

A better understanding of the biology and feeding habits of H. armigera on its many hosts is essential to understand its adaptation to different environments and to formulate successful management practices to maintain this pest at numbers below the economic threshold for crop damage. Our results suggest that the dicotyledonous species studied were more suitable for increasing the H. armigera population. However, further studies focusing on the performance of populations in the field are recommended, to confirm the role of host-plant suitability in the persistence of H. armigera. Although our results are based on laboratory observations, this study provides insights into the dynamics of a polyphagous pest recently introduced into Brazil.

Acknowledgments

We thank Celso Omoto for a critical review and Janet W. Reid from JWR Associates for revising the English text. This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)/Programa Nacional de Pós Doutorado (PNPD: 2014.1.93.11.0), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq: 459969/2014-5), and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP: 2014/16609-7).

References Cited

- Berdegué M., Reitz S. R., Trumble J. T. 1998. Host plant selection and development in Spodoptera exigua: do mother and offspring know best? Entomol. Exp. Appl. 89: 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Butt B. A., Cantu E. 1962. Sex determination of lepidopterous pupae. USDA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Mitchell A., Mitter C., Regier J., Matthews M., Robertson R. 2008. Molecular phylogenetics of Heliothinae moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae: Heliothinae), with comments on the evolution of host range and pest status. Syst. Entomol. 33: 581–594. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J. P., Zalucki M. P. 2014. Understanding Heliothine (Lepidoptera: Heliothinae) pests: what is a host plant? J. Econ. Entomol. 107: 881–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czepak C., Albernaz K. C., Vivan L. M., Guimarães H. O., Carvalhais T. 2013. First reported occurrence of Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Brazil. Pesq Agropec Trop. 43: 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Fefelova Yu. A., Frolov A. N. 2008. Distribution and mortality of corn earworm (Helicoverpa armigera, Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) on maize plants in Krasnodar Territory. Entomol. Rev. 88: 480–484. [Google Scholar]

- Fitt G. P. 1989. The ecology of Heliothis species in relation to agroecosystems. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 34: 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Greene G. L., Leppla N. C., Dickerson W. A. 1976. Velvetbean caterpillar: a rearing procedure and artificial medium. J. Econ. Entomol. 69: 487–488. [Google Scholar]

- Jallow M.F.A., Zalucki M. P. 2003. Relationship between oviposition preference and offspring performance in Australian Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Aust. J. Entomol. 42: 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy G. G., Storer N. P. 2000. Life systems of poplyphagous arthropod pests in temporally unstable cropping systems. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45: 467–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitching R. L., Zalucki M. P. 1983. A cautionary note on the use of oviposition records as host plant records. Aust. Entomol. Mag. 10: 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kriticos D. J., Ota N., Hutchison W. D., Beddow J., Walsh T., Tay W. T., Borchert D. M., Paula-Moreas S. V., Czepak C., Zalucki M. P. 2015. The potential distribution of invading Helicoverpa armigera in North America: is it just a matter of time? PLoS One 10: e0119618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite N. A., Alves-Pererira A., Corrêa A. S., Zucchi M. I., Omoto C. 2014. Demographics and genetics variability of the new world Bollworm (Helicoverpa zea) and the old world Bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) in Brazil. Plos One 9: e113286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Li Z., Gong P., Wu K. 2004. Life table of the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepdoptera: Noctuidae), on different host plants. Env. Entomol. 33: 1570–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Maelzer D. A., Zalucki M. P. 1999. Analysis and interpretation of long-term light-trap data for Helicoverpa spp. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Australia: the effect of climate and crop host plants. Bull. Entomol. Res. 89: 455–464. [Google Scholar]

- (MAPA) Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento . 2014 Combate á praga Helicoverpa armigera. MAPA, Brasília, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Mitter C., Poole R. W., Matthews M. 1993. Biosystematics of the Heliothinae (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Annu. Rev. Entomol. 38: 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Murúa M.G., Scalora F.S., Navarro F.R., Cazado L.E., Casmuz A., Villagrán M.E., Lobos E., Gastaminza G. 2014. First record of Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Argentina. Fla Entomol. 97: 854–856. [Google Scholar]

- North American Plant Protection Organization . 2014. Detection of old world Bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) in Puerto Rico. (protocol://www.pestalert.org/oprDetail.cfm?oprID=600).

- R Development Core Team (version 3.2.1). 2015. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Scott L. J., Lawrence N., Lange C. L., Graham G. C., Hardwick S., Rossiter L., Dillon M. L., Scott K. D. 2006. Population dynamics and gene flow of Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on cotton and grain crops in the Murrumbidgee Valley. Aust. J. Econ. Entomol. 99: 155163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. P., Ballal C. R., Poorani J. 2002. Old World bollworm Helicoverpa armigera, associated Heliothinae and their natural enemies. Bangalore, India, Project Directorate of Biological Control, Technical Bulletin. 31: iii+135 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Tay W. T., Soria M. F., Walsh T., Thomazoni D., Silvie P., Behere G. T., Anderson C., Downes S. 2013. A brave new world for an old world pest: Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Brazil. PLoS One 8: e80134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teakle R. E., Byrne V. S. 1988. Food selection by larvae of Heliothis armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on grain sorghum. J. Aust. Entomol. Soc. 27: 293–296. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. K. 1988. Evolutionary ecology of the relationship between oviposition preference and performance of offspring in phytophagous insects. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 47: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- van Lenteren J. C., Noldus L.P.J.J. 1990. Whitefly- plant relationship: behavioral and ecological aspects, pp. 47–89. In Gerling D. (ed.), Whiteflies: their bionomics, pest status and management. Intercept, Andover, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wardhaugh K. G., Room P. M., Greenup L. R. 1980. The incidence of Heliothis armigera (Hübner) and H. punctigera Wallengren (Lepidoptera? Noctuidae) on cotton and other host-plants in the Namoi Valley of New South Wales. Bull. Entomol. Res. 70: 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zalucki M. P., Daglish G., Firempong S., Twine P. H. 1986. The biology and ecology of Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) and H. punctigera Wallengren (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Australia: what do we know? Aust. J. Zool. 34: 779–814. [Google Scholar]

- Zalucki M. P., Murray D.A.H., Gregg P. C., Fitt G. P., Twine P. H., Jones C. 1994. Ecology of Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) and H. punctigera (Wallengren) in the inland of Australia: larval sampling and host plant relationships during winter and spring. Aust. J. Zool. 42: 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zalucki M. P., Clarke A. R., Malcolm S. B. 2002. Ecology and behaviour of first instar larval Lepidoptera. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 47: 361–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]