Abstract

Metagenomics allows the study of genes related to xenobiotic degradation in a culture-independent manner, but many of these studies are limited by the lack of genomic context for metagenomic sequences. This study combined a phenotypic screen known as substrate-induced gene expression (SIGEX) with whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing. SIGEX is a high-throughput promoter-trap method that relies on transcriptional activation of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene in response to an inducing compound and subsequent fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate individual inducible clones from a metagenomic DNA library. We describe a SIGEX procedure with improved library construction from fragmented metagenomic DNA and improved flow cytometry sorting procedures. We used SIGEX to interrogate an aromatic hydrocarbon (AH)-contaminated soil metagenome. The recovered clones contained sequences with various degrees of similarity to genes (or partial genes) involved in aromatic metabolism, for example, nahG (salicylate oxygenase) family genes and their respective upstream nahR regulators. To obtain a broader context for the recovered fragments, clones were mapped to contigs derived from de novo assembly of shotgun-sequenced metagenomic DNA which, in most cases, contained complete operons involved in aromatic metabolism, providing greater insight into the origin of the metagenomic fragments. A comparable set of contigs was generated using a significantly less computationally intensive procedure in which assembly of shotgun-sequenced metagenomic DNA was directed by the SIGEX-recovered sequences. This methodology may have broad applicability in identifying biologically relevant subsets of metagenomes (including both novel and known sequences) that can be targeted computationally by in silico assembly and prediction tools.

INTRODUCTION

The massive influx of novel sequence data derived from next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, in the context of both individual genomes (1) and metagenomes (2, 3), has far outstripped efforts to link those sequences to specific organisms and biological functions (4). Techniques such as quantitative PCR (qPCR) (5), microarrays (6), clone libraries (7), and stable-isotope probing (8) have been used successfully to identify organisms potentially involved in biodegradation. Substrate-induced gene expression (SIGEX) was proposed as a method for uncovering novel catabolic operons from metagenomes (9–12). SIGEX is a promoter trap method based on single-cell sorting of clones from a plasmid library using flow cytometry (FCM), where metagenomic clones of interest are identified by the increased expression of a downstream fluorescent reporter gene in the presence, but not in the absence, of an inducing compound. SIGEX was initially perceived as having great potential for mining genes from metagenomic samples in a high-throughput manner, without requiring prior knowledge of the sequences being screened for (13–15). However, SIGEX, and metagenomic promoter traps in general, has not lived up to this potential. In this study, we address several issues, described below, that have limited the use of SIGEX and demonstrate that this method may be used to aid characterization of a metagenome derived from aromatic hydrocarbon (AH)-contaminated soil.

AHs are common environmental chemicals that also encompass a wide variety of toxic and carcinogenic substances (16–18). They occur naturally in soil and are formed as by-products of combustion. Although the structure of AHs imparts a relatively long environmental half-life (19), most can be mineralized under both oxic and anoxic conditions (20) by a variety of microbial species (21–23). Many studies have examined AH-degrading microbes and their functional genes through culture-based techniques (19, 24, 25), which are limited, since most strains are resistant to culture using existing procedures (26). There is now a good understanding of the specific enzymes and pathways (27) involved in aromatic degradation at contaminated sites, particularly regarding the terminal dioxygenases that perform the first step in aerobic aromatic metabolism (28, 29). However, biochemical characterization of degradation genes on a case-by-case basis cannot keep pace with the rate of discovery of ostensibly novel genes found using metagenomic methods. Furthermore, the mechanisms by which many biodegradation genes (e.g., polyaromatic hydrocarbon [PAH]-degrading genes) are regulated are still unknown.

In this work we have carried out a case study that combines SIGEX and NGS. We have used a relatively simple metagenome derived from an enrichment culture of a PAH-contaminated site to demonstrate the utility of a modified SIGEX protocol in recovering and characterizing differentially regulated genes from a soil metagenome. We examine four important factors that have limited the use of SIGEX: (i) the difficulty inherent in obtaining high-quality metagenomic DNA for cloning, (ii) the potential lack of compatibility between host transcriptional machinery and metagenomic DNA, (iii) the difficulty associated with measurement of gene expression changes between heterogeneous populations, and (iv) the challenge of obtaining upstream and downstream sequences not contained on the SIGEX-cloned metagenomic fragment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, strains, and growth of bacteria.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Antibiotics were added from stocks to their appropriate final concentrations: ampicillin (Amp) to 100 μg/ml, chloramphenicol to 10 μg/ml, kanamycin to 10 μg/ml, and erythromycin to 0.3 μg/ml. Dilute LB (dLB) was made at 1:10 strength relative to LB (Lennox L broth; Invitrogen), and if indicated, maltose was added to 2% (dLB/M). Dilute M9 medium (dM9) contained 1× M9 salts, 1% pyruvate, 0.1% Casamino Acids (Difco), and trace elements (30). The vector pMMeb was used for metagenomic library creation. It is derived from the Bacillus-Escherichia coli shuttle vector pAD123 and carries a unique multicloning site (MCS) upstream of a promoterless green fluorescent protein (GFP) (31).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Use in this study |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− Δ(argF-lac)169 ϕ80dlacZ58(M15) ΔphoA8 glnV44(AS) λ− deoR 481 rfbC1 gyrA96(Nalr) recA1 endA1 thiE1 hsdR17 | Routine cloning strain |

| DH10b | F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK λ− rpsL nupG/pMON14272/pMON7124 | High-efficiency electroporation for ligated plasmid libraries, host for several SIGEX plasmid libraries |

| GS071 | F− (araD139)B/r Δ(argF-lac)169 λ− e14− flhD5301 Δ(fruK-yeiR)725(fruA25) relA1 rpsL150(Strr) rbsR22 Δ(fimB-fimE)632(::IS1) deoC1 soxRS | Derived from MC4100; used for testing for endogenous SoxRS regulators in paraquat inducible clones |

| NR6112 | F′ lac pro Δ(lac pro) ara thi rfa | Deep rough mutant; used as a library host when membrane permeability to large hydrophobic molecules was required (68) |

| Bacillus cereus 6A5 spo0A | Δspo0A | Bacillus host (derived from ATCC 14579) for SIGEX libraries; Emr marker inserted in sporulation genes (see the methods in the supplemental material) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAD123 (5,938 bp) | pBR322 (E. coli), pTA1060 (G+ rolling-circle replication for Bacillus); GFP reporter gene; Cmr Apr | Promoterless gfpmut3a with 3 upstream stop codons (31) |

| pMUTIN4 (8,610 bp) | Emr Apr | Contains a cloning site where DNA fragments are inserted for creating the corresponding chromosomal gene knockouts in Bacillus species (69) |

| pMMeb (5,954 bp) | See pAD123 | Novel MCS for cloning low-, mid-, and high-GC digested DNA |

DNA manipulations and molecular methods.

Molecular methods were performed as described by Sambrook and Russell (30). For routine plasmid isolation from E. coli, the Wizard Plus SV kit or the Wizard Midiprep kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs (NEB).

Soil samples and treatments.

Rock Bay (Victoria Harbor, British Columbia, Canada; samples were donated by BC Hydro and Transport Canada) was the location of various industrial activities since ca. 1862. Runoff from a coal gasification plant, tannery, propane tank farm, concrete batch plant, and asphalt plant resulted in significant soil contamination consisting of coal gasification by-products, with PAH concentrations ranging from 475 to 12,600 μg/g of soil (32). Soil was homogenized before incubation in a 20% (wt/vol) bioslurry (in sterile Milli-Q water) in duplicate BioFlo 110 bioreactors. To enrich for organisms involved in aerobic degradation of aromatics, the slurry was agitated and aerated constantly for 90 days at a pH of 6.5 to 8.0, kept at 25°C. Samples of the bioslurry, taken every 15 days beginning on day 0, were stored at −80°C (with glycerol to 15%). Day 0 to 60 samples from this bioslurry showed a significant decrease or elimination of aromatic compounds, including complete elimination of naphthalene, acenaphthene, fluorene, and phenanthrene, and an overall 60% decrease, by mass, of priority PAHs (32) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Petawawa was the source of an explosive-contaminated sandy soil, from the antitank firing position of a firing range, donated by Sylvie Brochu (Life Cycle of Munitions Group, Energetic Materials Section, Defense Research and Development Canada [DRDC], Valcartier, Québec, Canada). The 2.5 cm of topsoil was collected with an acetone-rinsed stainless steel scoop; samples were stored immediately in polyethylene bags and kept in the dark at 4°C until use in bioslurry experiments done as described above for Rock Bay soil.

Metagenomic DNA isolation.

The isolation of DNA from soils is an ongoing technical challenge for metagenomics studies. In this study, the high levels of hydrocarbon contamination in the soil resulted in a reduced yield of high-quality DNA. Therefore, in order to obtain sufficient quantities of DNA for cloning and sequencing, samples from 5 time points (days 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60) from the Rock Bay bioslurry glycerol stocks were combined from duplicate reactors for a total of 10 samples each containing 25 ml of slurry. Following centrifugation at 4,500 × g for 10 min, a combined total of 3.0 g sediment was collected and rinsed with one volume of wash buffer (10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris, 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 8.0). DNA was extracted using the Mo-Bio PowerMax soil DNA isolation kit, ethanol (EtOH) precipitated, and resuspended in 1 ml of 2 mM Tris (pH 8.0).

Preparation of metagenomic libraries.

Metagenomic insert DNA was prepared by partial digestion of 5 μg of DNA with Sau3AI. Purified DNA was run on an agarose gel and showed elimination of the high-molecular-weight (HMW) fraction and production of fragments from 0 to 12 kb with approximately even density (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The desired size range was isolated from the gel using GeneClean and then purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and EtOH precipitation. Remaining contaminants were eliminated by precipitation with polyethylene glycol (PEG) as follows. DNA dissolved in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) was mixed with one volume of 35% PEG 8000–30 mM MgCl2, vortexed, and centrifuged at room temperature at 21,000 × g for 45 min. Pelleted DNA was rinsed with 70% EtOH. Size-fractionated metagenomic DNA was resuspended in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and ligated using T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen) to 100 ng vector DNA digested by BamHI (5:1 insert/vector molar ratio) for 18 h at 4°C. Ligated DNA was purified using the PureLink PCR kit (Invitrogen).

FIG 1.

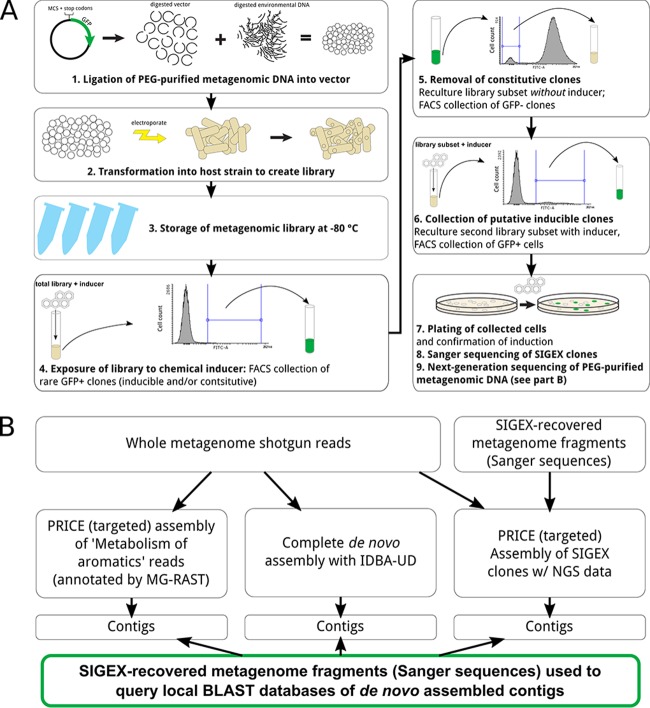

Substrate-induced gene expression (SIGEX) screening as used in this study. (A) Workflow used to obtain inducible clones from a metagenomic library. Several rounds of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) were used to select GFP-positive or -negative cells in the presence and absence, respectively, of an inducing compound of interest (in this study, aromatic hydrocarbons). Using this approach, a complex metagenomic library of millions of clones can be reduced to a simpler subset of differentially regulated clones for detailed analysis. (B) The bioinformatics pipeline used to determine the genomic context of SIGEX-recovered clones. Shotgun-sequenced metagenomic DNA was assembled using two alternative procedures. First, the IDBA-UD algorithm used all sequence reads to achieve iterative de novo assembly. Second, the PRICE algorithm was used to achieve targeted assembly of a reduced subset of sequence reads. The contigs generated by each assembly were used to compile a local BLAST database, which was then queried using Sanger sequences of SIGEX clones to identify those contigs containing phenotypically relevant sequence.

To transform ligated metagenomic DNA libraries, electrocompetent E. coli was prepared using cells grown in salt-free LB (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, no NaCl) but otherwise prepared according to reference 30. Transformations were carried out in an E. coli Gene Pulser set at 2.5 kV using a 2-mm-gap electroporation cuvette (Fisher). Following recovery in 1 ml S.O.C. medium (Invitrogen), 4 ml LB-Amp was added, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C, with shaking at 220 rpm, for 16 h. Cultures from individual transformations were pooled and resuspended in LB-Amp with 25% glycerol in a volume 1/10 the original culture volume and stored at −80°C until use; this comprised the library stock.

Flow cytometry analysis.

The BD Biosciences FACSAria II flow cytometer was fitted with a quartz cuvette flow cell operated at 70 lb/in2 using the 70-μm nozzle, resulting in sheath flow velocities of ∼6 m/s at the point of interrogation. The light source was a nonpolarized 488-nm laser (Coherent Sapphire solid state) operated at 13 mW (33). Side-scattered (SSC) light was filtered by a 530/20 band-pass filter for analysis of GFP fluorescence. Parameters were acquired using logarithmic amplification over 5 decades, with forward scatter (FSC) and SSC thresholds of 200. Identification of bacterial populations and sorting are described in the methods section in the supplemental material and shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material. Plots and histograms were created using Flowing software (Perttu Terho, http://www.flowingsoftware.com).

SIGEX induction protocol and screening libraries for individual clones.

To obtain individual clones from a library, a scheme similar to differential fluorescence induction (DFI) (34, 35) was employed for cell sorting (Fig. 1A). The entire metagenomic library was propagated in a single liquid culture for each induction experiment (see below for details), and the top 1% of GFP-expressing cells was collected from the total library in the presence of inducing compounds and recultured. This subset of the library (GFP positive in the presence of inducer) was then applied to the cytometer in the absence of inducer, and cells exhibiting the least GFP expression (bottom 10%) were collected and recultured. Finally, this subset of the library was again induced, and the cells expressing GFP at the highest levels (top 0.1% and 1%, separately) were sorted and plated for analysis. Putative inducible clones were confirmed as inducible using flow cytometric analysis of individual clones grown in monoculture with and without inducer as well as measurement of GFP in microtiter plates (see the methods section in the supplemental material).

Prior to FCM analysis, a 100-μl aliquot of the library was inoculated into 5 ml of medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. When using frozen stocks, a 1-h recovery period in 1 ml S.O.C. was used. Cultures were then rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 3 times before resuspension in medium. For samples requiring induction, the inducing compounds were added at the following concentrations: 100 μM salicylate (≥99.5%; Sigma), benzoate (≥99.0%; Sigma), naphthalene (≥99.0%; BDH Chemicals Ltd.), catechol (≥99.0%; Sigma), phenol (Ultra-Pure Buffer Saturated; Invitrogen), and phenylacetic acid (Eastman Kodak, lot 574) and 10 μM fluoranthene (Moltox), pyrene (Moltox), and phenanthrene (>98.0%; Aldrich). When defined mixtures of compounds were used as inducers, they were added at an equimolar concentration for a total of 100 μM for AHs and 10 μM for PAHs. Negative controls used a culture of the strain containing an empty vector treated with medium (and solvent if applicable). Cultures were grown at 37°C (with shaking at 220 rpm) for 18 h. Cells were harvested at 10,000 × g for 3 min, washed 3 times in one volume of PBS, and resuspended in 1 ml PBS. This suspension was then used to make dilutions at densities resulting in approximately 3,000 events per second on the flow cytometer.

DNA sequencing.

Seven micrograms of metagenomic DNA (concentrated and purified by PEG precipitation) was used to create two TruSeq genomic DNA (gDNA) libraries for whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing (performed by Genome Québec, Montréal, Québec, Canada). The libraries had average insert sizes of 255 bp and 447 bp (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Two lanes of Illumina sequencing (HiSeq 2000) were obtained from the 255-bp insert library and one lane from the 447-bp library, using 100-bp paired-end reads.

Clones recovered using SIGEX were end sequenced by BioBasic (Mississauga, Canada) using the primers GfpSeq (5′-GTTGCATCACCTTCACCCTCTCCACTGACAG-3′) and pADLeft (5′-ACCTGACGTCTAAGAACCCATTATT-3′), which anneal upstream of the GFP and downstream of the MCS, respectively, on pMMeb; subsequent reads were obtained by primer walking. The Sanger reads were aligned manually using BioEdit, and vector sequence was removed. Any regions of overlap between reads were used to build a consensus sequence for each SIGEX-recovered clone. These sequences were used to query the NCBI nr protein database using tBLASTx (36) with a cutoff of 1e−5. BLAST results were analyzed with Epos BlastViewer and Geneious.

MG-RAST (37) was used to determine functional and taxonomic relationships (http://metagenomics.anl.gov/). We uploaded the FASTQ files obtained from Illumina sequencing to the MG-RAST server, as well as several metagenomic assemblies in FASTA format. FASTQ reads were processed using the recommended MG-RAST pipeline configuration to ensure that comparison to other data sets could be performed. Coverage of the assembled sequence was computed for each contig from the IDBA-UD output file using the following formula: coverage = (number of reads on contig × 100 bp)/(contig length in bp). SEED subsystem annotations were used to identify any features annotated with “metabolism of aromatics”; these reads were assembled using IDBA-UD to obtain contigs putatively containing only aromatic-metabolizing genes.

Assembly and analysis of Illumina sequence data. (i) De novo assembly.

Figure 1B summarizes the bioinformatics workflow used to complement the sequence data obtained from Sanger sequencing of the SIGEX-isolated metagenome fragments. IDBA-UD (38) was run using a kmer size iterated from 20 to 100 with a step size of 1, following a precorrection step using a kmer size of 60. PRICE was used to assemble metagenomic sequences directly flanking known subsets of the metagenome using paired-end information (39). This tool can expand an initial set of user-specified sequences using NGS read mapping and local assembly. We used 20 cycles of PRICE, using default parameters, to expand the SIGEX clone sequences (Sanger reads). A second subset of the metagenome, the “Metabolism of aromatics” reads (as annotated by the MG-RAST pipeline and preassembled using IDBA-UD in order to collapse overlapping sequences), was also expanded using 20 cycles of PRICE.

(ii) Mapping SIGEX clones to metagenomic contigs.

A local BLAST database composed of assembled contigs was used to determine the sequence similarity and overlap shared between Sanger-sequenced SIGEX clones and NGS data. SIGEX clone sequences were used as queries with an E value cutoff of 1e−5 using BLASTn. After sorting hits by E value, the hit with the longest overlap was used to determine which contig was used for mapping that clone. Each SIGEX clone sequence was then aligned to its respective best-match contig using the “map to reference” feature of Geneious (up to 5 iterations using the highest sensitivity). Where multiple SIGEX clones mapped to the same contig, alignment with MUSCLE (40) was used to create dendrograms and visualize the alignments to examine locations of overlap and polymorphism.

Sequence accession numbers.

Sequence data from this project are available under NCBI BioProject PRJNA202911. The Rock Bay NGS sequences can be found under BioSample SAMN02440304. Raw data are available at the Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP034518, with assembled contigs under LNAO00000000, LNAP00000000, and LNAQ00000000. Data are available on MG-RAST under accession numbers 4494328.3, 4494329.3, 4494326.3, 4494327.3, 4494330.3, and 4514465.3, with assembled contigs at MG-RAST accession number 4494331.3 (project: Metagenome of a PAH-Contaminated Soil). Sanger reads of SIGEX-recovered clones are available under GenBank accession numbers KU043044 to KU043112.

RESULTS

Proof-of-principle SIGEX experiments.

Several experiments were performed to ensure that our modified substrate-induced gene expression (SIGEX) system would function as intended. We first used a Lac− host, E. coli DH10b, to screen a library derived from E. coli C600 (Lac+) genomic DNA (library designated EC-600 for E. coli strain C600) using IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and paraquat as inducers. In both cases, we recovered inducible genes that were biologically relevant to the inducer: the lacZ gene was recovered using IPTG induction, and pqiB, a known paraquat-inducible gene, was recovered using paraquat induction (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Next, we evaluated our methodology using a metagenomic library made using DNA extracted from a soil. An existing sample from an explosives-contaminated site (designated EXP-1 for explosives library 1) was used to create this library, and paraquat was used as the inducer in the SIGEX protocol. This experiment yielded a wide variety of clones originating from diverse taxa, each of which was found to be highly inducible by paraquat in the E. coli host (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Sequencing revealed that the metagenomic fragments encoded functions related to the oxidative stress response. Notably, the inducibility of a subset of these clones was abolished by transformation into a SoxRS− strain of E. coli (lacking the genes responsible for the superoxide stress response), demonstrating that host transcription factors were responsible for GFP induction in at least some clones. Most of the sequences possessed low amino acid identity (range, 29 to 66%) to their closest BLAST match in the nr database.

SIGEX library construction.

A metagenomic library containing inserts between 1 and 10 kb was created for the SIGEX experiments (named PAH-E, where PAH refers to the fact that the soil was contaminated with PAHs and E represents the E. coli host). This library was made using DNA isolated from an enrichment culture of the Rock Bay hydrocarbon-contaminated site. While a variety of methods for purifying soil DNA have been published (41), we observed that the precipitation of metagenomic DNA with PEG 8000 following restriction digestion was the best way to eliminate a high proportion of small (<1-kb) inserts. Based on dilutions of the initial transformation of ligated library clones into E. coli, approximately 1.6 × 106 inserts of >1 kb were present in ≥90% of clones in the PAH-E library. A second library, PAH-B (where B represents a Bacillus host), was generated using plasmid DNA isolated from the PAH-E library with subsequent transformation into Bacillus cereus.

Analysis of aromatic-inducible genes recovered from the PAH-E and PAH-B libraries.

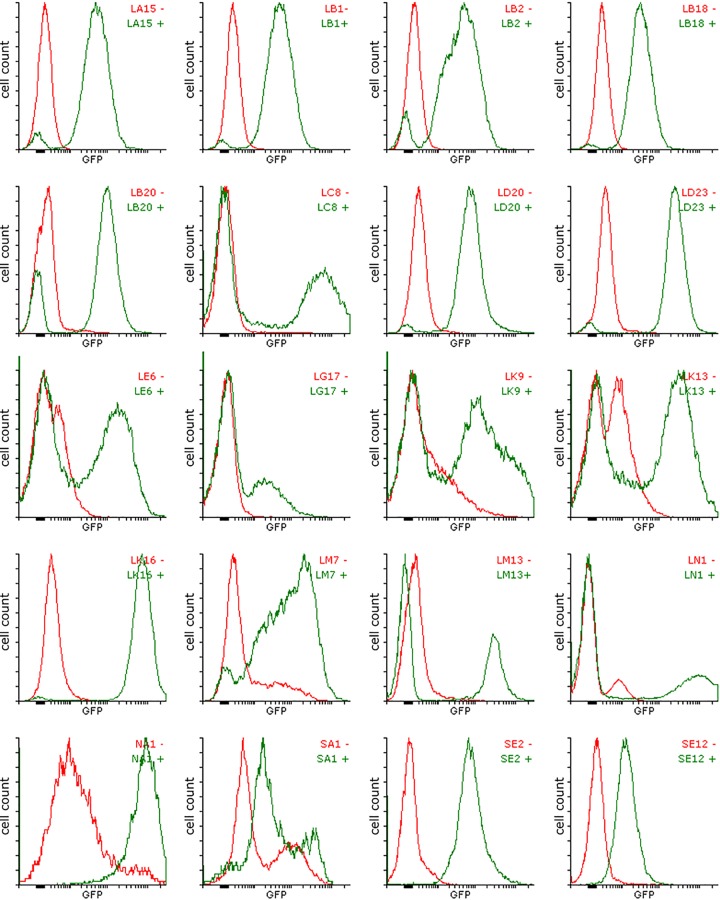

A mixture of low-molecular-weight (LMW) aromatic compounds as well as several individual AHs were used to interrogate the PAH-E library using the SIGEX induction protocol. Three hundred eighty-four putative LMW (with fewer than 3 benzene moieties) aromatic-inducible clones recovered using SIGEX were tested for inducibility in microtiter plates (see the methods section in the supplemental material). Of these, the 96 clones showing the highest levels of induction in the plate reader assay were subjected to restriction digestion of plasmid DNA to determine uniqueness. Twenty unique clones were present, with inserts ranging in size from 1.1 to ∼7 kb, and each was end sequenced. The inducibility of these clones was examined using FCM (Fig. 2) and the microtiter plate assay (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Clones were named according to the compound used for induction in the SIGEX screen (S for salicylate, B for benzoate, N for naphthalene, and L for the mixture of LMW compounds) and by their position in the 384-well plate used for screening (row and column). The sequences reveal that most clones contain genes with high similarity to aromatic-degrading operons from the genus Pseudomonas (14 of the 20 clones). No aromatic-inducible clones that aligned to sequences from phyla other than Proteobacteria were recovered, and 16 of the 20 clones aligned to Gammaproteobacteria sequences.

FIG 2.

Histograms of GFP expression for aromatic-inducible clones isolated using SIGEX from a metagenomic library derived from an aromatic hydrocarbon-contaminated site. The expression pattern of these clones reveals the variability in dynamic range that exists among the different promoters that were recovered. Cultures of E. coli containing each metagenomic clone were grown at 37°C for 18 h in dM9 before the addition of inducer; inductions were carried out for 3 h under identical growth conditions. Red lines indicate cultures grown without inducer, and green lines indicate cultures grown in the presence of a 100 μM LMW aromatic mixture (containing equimolar quantities of benzoate, salicylate, catechol, phenol, phenylacetic acid, and naphthalene). Ten thousand events were recorded for each sample.

Based on tBLASTx searches of the Sanger reads of SIGEX clones, the most common sequences (found in clones SA1, LD20, LD23, LK13, LK16, LM13, and LN1) show similarity to nahG (encoding salicylate hydroxylase) coupled with nahR (encoding an aromatic-inducible LysR-type transcriptional regulator [LTTR]). We also identified genes for multiple efflux transporters (LA15, LB1, LB2, LB18, and SE12) and a transposase (LC8) and a variety of other genes encoding proteins with putative metabolic functions (NA1, SE2, SE12, LB20, LE6, LG17, LK9, and LM7). A detailed analysis of these sequences is presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of genes that were identified by tBLASTx within the sequences of aromatic-inducible clones recovered from the PAH-E library and their inducibility as measured by FCMa

| Clone | Fold induction by 100 μM LMW aromatics | Matched protein(s) (accession no.) | E value (bit score) | Organism | Order | Comments (reference[s]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA1 | 11.86 | XylU (CAC86830.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; putative transposases (AF043544.2, AF043544.2) upstream | 0.0 (692) | Pseudomonas putida plasmid pWW0 | Pseudomonadales | Partial toluene degradation operon (56) |

| SA1 | 1.81 | NahT chloroplast ferredoxin-like protein (AAP44221.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; NahG (AAP44222.1) salicylate hydroxylase and OprD (NZ_AJMR01000068.1) upstream | 0.0 (719) | Pseudomonas sp. strain ND6 plasmid pND6-1 | Pseudomonadales | Aligns to plasmid pND6-1, a naphthalene degradation plasmid (57); contains NahG gene and degrades salicylate to catechol in E. coli |

| SE2 | 60.15 | SgpA (ACO92374.1)m first 13 bp of gene are transcriptionally fused to GFP; SgpR (ACO92380.1) divergently transcribed | 0.0 (941) | Pseudomonas putida plasmid pAK5 | Pseudomonadales | SgpA is a salicylate 5-hydroxylase ferredoxin reductase, the first gene in a salicylate-gentisate pathway; SgpR, an LTTR, is the putative regulator of the operon |

| SE12 | 9.80 | PSF113_1991 (AEV62003.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; upstream is a MarR family protein (AEV62002.1) | 1e−122 (215) | Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 | Pseudomonadales | MarR regulates multiple antibiotic resistance through upregulation of efflux pumps, etc., and is often activated by AHs (58, 59) |

| LA15 | 52.36 | Acriflavin resistance protein (ADQ85831.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP | 3e−102 (359) | Methylovorus strain sp. MP688 | Methylophilales | Efflux pump involved in antibiotic resistance |

| LB1 | 29.50 | Acriflavin resistance protein (ADQ85831.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP | 9e−126 (457) | Methylovorus sp. strain MP688 | Methylophilales | Efflux pump involved in antibiotic resistance |

| LB2 | 41.59 | Acriflavin resistance protein (ADI29216.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP | 3e−174 (617) | Methylotenera versatilis 301 | Methylophilales | Efflux pump involved in antibiotic resistance |

| LB18 | 17.89 | Acriflavin resistance protein (AEM51786.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP | 1e−127 (365) | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia JV3 | Xanthomonadales | Efflux pump involved in antibiotic resistance |

| LB20 | 47.16 | NdsR (BAC53588.1) transcribed divergently from GFP; promoter driving GFP expression is from a salicylate hydroxylase (BAC53589.1) | 7e−126 (457) | Pigmentiphaga sp. strain NDS-2 | Burkholderiales | NdsR is a putative LTTR, part of a salicylate degradation operon |

| LC8 | 69.24 | DDE-type transposase (AFM32558.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; upstream is an LTTR transcribed toward GFP (AFM32556.1); divergently transcribed is NahG | 0.0 (690) | Pseudomonas stutzeri CCUG 29243 | Pseudomonadales | Similar to a transposon involved in naphthalene degradation |

| LD20 | 37.91 | NahG (AAD02146.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; divergently transcribed is NahR (AAD02145.1) | 0.0 (549) | Pseudomonas stutzeri (GI:4104761) | Pseudomonadales | GFP is fused to the first gene in this salicylate degradation operon (60) |

| LD23 | 80.28 | Salicylate hydroxylase (AAY21679.2) transcriptionally fused to GFP; divergently transcribed NahR (AAY21678.2) | 0.0 (899) | Pseudomonas fluorescens PC20 plasmid pNAH20 | Pseudomonadales | GFP is fused to the first gene in this salicylate degradation operon; similar to plasmid pNAH20 (61) |

| LE6 | 37.34 | SalA (AAZ08064.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; divergent BphR2 (AAZ08063.1) | 0.0 (650) | Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 | Pseudomonadales | Naphthalene degradation operon; cross regulated in vivo by BphR1 and BphR2 (62, 63) |

| LG17 | 17.39 | Acyl carrier protein phosphodiesterase (ABA73175.1) fused to GFP; membrane protein (ABA73174.1) upstream; partial LTTR protein (ABA73173.1) divergently transcribed | 4e−173 (355) | Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 | Pseudomonadales | Putative antibiotic resistance genes; the acyl carrier protein contains a conserved azoreductase domain (PRK00170; E value, 7.06e−98) and a flavodoxin-like fold (pfam02525; E value, 3.95e−57); the LTTR contains a MarR domain |

| LK9 | 16.00 | LTTR (AEY00105.1) transcribed divergently from GFP; further downstream and also divergent is an IclR type regulator (YP_004931645.1) | 6e−148 (531) | Oceanimonas sp. strain GK1 | Aeromonadales | Inducible by phenol; LTTR shows similarity to BenR from Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus ATCC 49840 (YP_005428200.1); in Oceanimonas, a muconate and chloromuconate cycloisomerase (AEY00106.1) is downstream of the promoter (64) |

| LK13 | 28.93 | Salicylate hydroxylase NahG (AAD02146.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; divergently transcribed NahR (AAD02145.1) | 0.0 (200) | Pseudomonas stutzeri (GI:4104761) | Pseudomonadales | Aligns to the same sequence as clone LD20 but represents a unique restriction fragment (60) |

| LK16 | 255.48 | Salicylate hydroxylase NahG (AAQ89673.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; NahR (AAQ89672.1) divergently transcribed | 0.0 (708) | Pseudomonas putida (GI:37220701) | Pseudomonadales | First gene in salicylate degradation gene cluster and NahR; this element is widely distributed among biphenyl-utilizing bacteria (65) |

| LM7 | 7.19 | Proteins NarD (AAG34371.1), NarK (AAG34372.1), and NarG (AAG34373.1) are divergently transcribed from GFP; only the promoter region of NarX (AAG34370.1) is present | 0.0 (697) | Pseudomonas fluorescens (GI:11344596) | Pseudomonadales | Putative nitrate/nitrite transporter (NarD), putative nitrate/nitrite transporter (NarK), and respiratory nitrate reductase alpha subunit (NarG); NarX is a nitrate/nitrite sensor protein (66, 67) |

| LM13 | 61.69 | NahG salicylate hydroxylase (ACV05012.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; NahR (ACV05020.1) is divergent | 0.0 (928) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain CGMCC 1.860 plasmid | Pseudomonadales | Nearly complete NahG gene is present; naphthalene degradation operon; aligns to same sequences as LN1 but at a different site |

| LN1 | 211.36 | NahG salicylate hydroxylase (ACV05012.1) transcriptionally fused to GFP; NahR (ACV05020.1) is divergent | 0.0 (878) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain CGMCC 1.860 plasmid | Pseudomonadales | Naphthalene degradation operon; aligns to same sequences as LM13 but at a different site; higher fold induction may be due to the closer proximity of GFP to the promoter |

Genes that were found to be transcriptionally fused to the GFP reporter, as well as genes that potentially regulate the promoters driving GFP expression, are described.

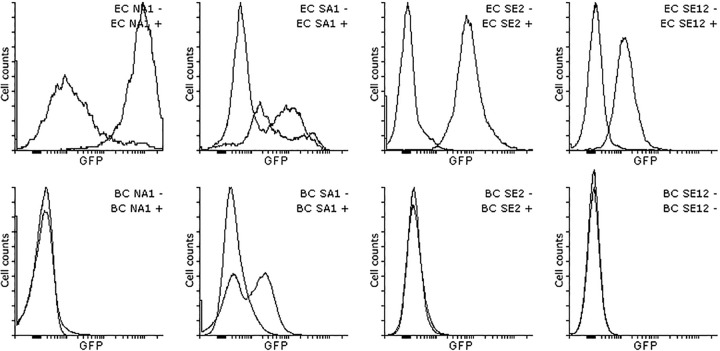

We postulated that the use of a Gram-positive host organism may be beneficial for screening genes that do not function in E. coli (12, 13). However, no inducible clones were recovered from the PAH-B library using the Gram-positive host B. cereus (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). In lieu of this, we directly transformed the B. cereus host with a small number of LMW-aromatic-inducible clones recovered using SIGEX from the PAH-E library in E. coli, and we subsequently measured their inducibility in B. cereus using FCM (Fig. 3). Three of 4 clones recovered using the E. coli host did not show any induction in the presence of LMW aromatic compounds in B. cereus. However, one clone, SA1, was also inducible in the B. cereus host (4.13-fold in B. cereus compared to just 1.8-fold in E. coli under the same growth conditions).

FIG 3.

Induction of naphthalene- and salicylate-inducible clones in B. cereus (bottom) and E. coli (top) hosts. The clones were recovered using SIGEX with an E. coli host; only clone S-A1 appears to be inducible in B. cereus.

Trends in GFP expression.

FCM analysis of cultures demonstrated that GFP expression of individual cells within a clonal population can vary dramatically. Figure S7 in the supplemental material shows histograms of GFP expression for four different clones isolated from the PAH-E metagenomic library (all shown in an uninduced state); the only difference between them is the metagenomic promoter driving GFP expression. As shown in Fig. S7A in the supplemental material, a typical population (white) expresses GFP in a Gaussian distribution. However, the pattern of GFP expression depends strongly on the genetic nature of the metagenomic sequence. With some clones, nearly identical expression patterns may exhibit vastly different mean values (see Fig. S7A in the supplemental material). The population shown in gray (with a mean of 2,158) has a higher mean than the population shown in white (with a mean of 80), the difference arising from the former exhibiting a long tail of uniformly GFP-expressing cells over a large dynamic range. Conversely, highly variable expression patterns can yield nearly identical means (see Fig. S7B in the supplemental material; light gray and white have means of 16,114 and 16,204, respectively). The results shown in Fig. S7B in the supplemental material suggest that the variation of GFP expression between cells within a population is a function of some unknown genetic determinant.

HMW aromatic inducers.

We attempted to use HMW PAH inducers (individually and in a mixture, at concentrations of 10 μM) in SIGEX experiments with the PAH-E and PAH-B libraries. None of these experiments yielded clones that were inducible by the PAHs. In total, analysis of >1,152 clones recovered with SIGEX using HMW PAH inducers was performed, but only false positives (i.e., clones expressing GFP unconditionally) were recovered.

De novo assembly of metagenomic sequences.

The Illumina sequencing produced a total of 1,251,018,284 reads (for a total of ∼125 gigabase pairs of sequence). We attempted de novo assembly with several algorithms; statistics associated with the contigs generated by each are shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. We found that IDBA-UD provided the highest N50, with a value of 9.1 kb when scaffolds were included. The longest contig was 608 kb, and the data set contained 143 contigs of ≥100 kb; 25% of total sequence length was contained in 1,998 sequences of ≥26,804 bp.

Using PRICE, we directed the de novo assembly of NGS data to metagenomic regions surrounding either (i) SIGEX-derived clones or (ii) the contigs assembled from reads annotated with “metabolism of aromatics” in the MG-RAST SEED subsystem classification (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). This provided two distinct ways to direct the assembly: using either the phenotypically characterized sequences garnered from SIGEX or a completely in silico approach based on annotations in MG-RAST. We found that, after 20 cycles of PRICE assembly, a comparable amount of total sequence was obtained (13.7 Mb for the MG-RAST-annotated aromatic assembly versus 15.2 Mb for the SIGEX clone-directed assembly). However, the MG-RAST-annotated reads provided a higher-quality assembly, with an N50 of 9.6 kb compared to an N50 of 4.6 kb obtained with the PRICE expansion of SIGEX clones.

Mapping aromatic-inducible clones to assembled metagenomic contigs.

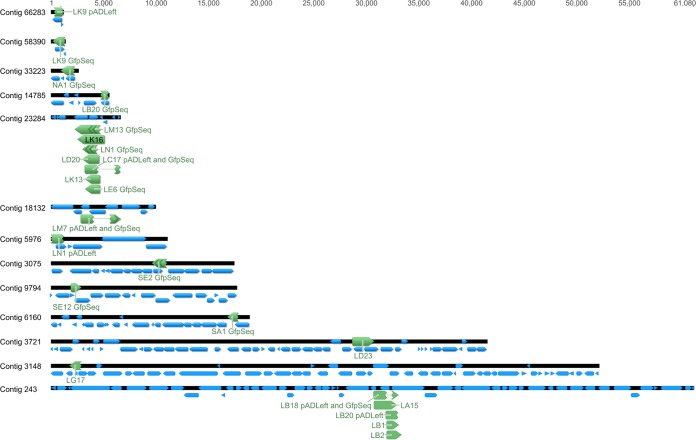

End-sequenced Sanger reads from each aromatic-inducible SIGEX clone were used as queries in BLAST searches of a database derived from de novo-assembled contigs. Each SIGEX clone aligned to contigs in the de novo-assembled NGS metagenome sequence with an E value of 0.0 in the BLAST results (Table 3 shows results for IDBA-UD contigs; see Table S4 in the supplemental material for alignment to other NGS assemblies). This indicates that a high degree of identity exists between de novo-assembled contigs and the Sanger-sequenced SIGEX clones. Since there were multiple hits for each Sanger read, the contig with the longest high-scoring pair to the SIGEX clone was used as the reference sequence for mapping in Geneious v. 6.1 (Biomatters Inc.). A graphical overview of SIGEX clones mapped to NGS-derived contigs is shown in Fig. 4. The predicted biological roles determined for the contigs using open reading frame (ORF) prediction (MetaGeneMark) (42) and subsequent BLAST searches are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 3.

Matches between SIGEX-recovered clones and contigs in the data set of assembled Illumina reads

| Clone | Best match to contig (length, bp) | Reference-mapped pairwise % identity | Predicted features on matched contig (species/strain) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA15 | Contig_243 (61,080) | 95.6 | Operon containing several efflux pumps (Methylotenera versatilis 301) |

| LB1 | Contig_243 (61,080) | 97.2 | See LA15 |

| LB18 | Contig_243 (61,080) | 100.0 | See LA15 |

| LB18 | Contig_243 (61,080) | 87.0 | See LA15 |

| LB2 | Contig_243 (61,080) | 97.8 | See LA15 |

| LB20 | Contig_14785 (5,488) | 97.9 | Type VI secretion protein, nitroreductase, and several hypothetical proteins downstream from DntR/NahR/LinR regulator (Pigmentiphaga sp.) |

| LB20 | Contig_243 (61,080) | 95.5 | See LA15 |

| LC17 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 87.2 | Salicylate degradation gene cluster (Pseudomonas stutzeri CCUG 29243 chromosome) |

| LC17 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 89.9 | See LC17 |

| LD20 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 89.9 | See LC17 |

| LD23 | Contig_3721 (41,449) | 81.2 | Operon containing nahR and nahG (Pseudomonas putida G7 plasmid pNAH7), benzoate transport protein genes (Pseudomonas sp.), and partial Xyl operon containing various aromatic oxygenase genes (Azotobacter vinelandii strain DJ) |

| LE6 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 89.3 | See LC17 |

| LG17 | Contig_3148 (52,066) | 97.0 | Contains a histidine kinase protein downstream from putative MarR regulator and ACP phosphodiesterase/azoreductase (Pseudomonas brassicacearum NFM421 and Pseudomonas mandelii) |

| LK13 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 89.4 | See LC17 |

| LK16 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 91.8 | See LC17 |

| LK9 | Contig_58390 (1,336) | 100.0 | LTTR (Oceanimonas sp.) and partial transposon (Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes) |

| LK9 | Contig_66283 (1,142) | 95.1 | Similar to a Fis family regulator (Pseudoxanthomonas spadix) and transposase Tra8 (Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes) |

| LM13 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 83.8 | See LC17 |

| LM7 | Contig_18132 (9,903) | 96.7 | Nitrite and nitrate sensor, transporter, and reductase proteins NarG, NarU, NarK, NarX/Q, NarL (Pseudomonas mandelii and Pseudomonas sp.) |

| LM7 | Contig_18132 (9,903) | 83.4 | See LM7 |

| LN1 | Contig_23284 (6,565) | 91.0 | See LC17 |

| LN1 (pALeft) | Contig_5976 (10,627) | 86.9 | Apparent chimeric sequence |

| NA1 | Contig_33223 (2,562) | 95.1 | Nitrotoluene catabolic gene cluster; similar to xyl genes from TOL plasmid (Pseudomonas sp. strain TW3) |

| SA1 | Contig_6160 (18,816) | 95.0 | Lower naphthalene-degrading pathway for catabolism of salicylate to acetyl coenzyme A and pyruvate (Pseudomonas putida strain NCIB 9816-4, plasmid pDTG1, bases 31917 to 51950 except for tnpA gene) |

| SE2 | Contig_3075 (17,374) | 97.9 | Salicylate/gentisate degradation gene cluster (Pseudomonas putida AK5, plasmid pAK5) |

| SE12 | Contig_9794 (17,614) | 99.3 | Operon containing efflux transporter and multidrug resistance proteins (Pseudomonas sp. strain GM78) |

| Avg | 92.4 |

BLAST searches were conducted on a local database of the IDBA-UD assembled contigs, using SIGEX clones as queries. BLAST hits were sorted by E value, and hits with longest query coverage are shown, as all hits had at least one match with an E value of 0.0.

FIG 4.

Overview of aromatic-inducible SIGEX-recovered clones (green arrows) mapped to NGS-derived contigs (black bars), showing ORFs predicted by MetaGeneMark (blue arrows). This demonstrates that the relatively small plasmid-based clones can be mapped to a larger genomic context to obtain sequence information downstream and upstream that would otherwise be impossible to obtain using SIGEX alone.

In addition to the IDBA-UD assembly, the SIGEX clones were also mapped to contigs assembled by PRICE (described above; see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Overall, the SIGEX clones mapped with the highest confidence to NGS contigs from the global de novo assembly performed by IDBA-UD (with an average contig size of 18.4 kb and nucleotide identity of 95.0% for mapped clones). However, in certain sporadic cases, we found that some SIGEX clones mapped to PRICE-assembled contigs that were longer than those from the IDBA-UD assembly (e.g., clone NA1 maps to a 2.6-kb contig from the IDBA-UD de novo assembly with 95.1% identity, compared to a 12.6-kb contig with 94.3% identity from the PRICE assembly; similarly, LK9-GfpSeq maps to a 1.3-kb IDBA-UD contig with 100% identity but to an 8.8-kb contig in the PRICE assembly with 99.3% identity).

DISCUSSION

Several proof-of-principle experiments done in this study demonstrated that the SIGEX system applied in this manner is capable of recovering both expected (characterized) and novel (uncharacterized) genes using a variety of DNA sources as input (including genomic DNA closely related to the host organism and metagenomic DNA that is distantly related to the host; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). However, the downstream analysis of clones recovered using SIGEX represents a major undertaking in itself. For each novel gene, a great deal of biochemical analysis and characterization must be done to determine its specific function. Therefore, in this study, we focused on the genetics of a relatively simple metagenome derived from an enrichment culture of a PAH-contaminated site as a case study to demonstrate the utility of SIGEX in combination with NGS.

Since the introduction of SIGEX in 2005 (9), relatively few laboratories have published data using this methodology. In this paper, we demonstrate key modifications that eliminate technical impediments to high-throughput screening and which should facilitate more widespread application of SIGEX to metagenomic screening. (i) The use of a vector containing a promoterless GFP gene was found to reduce background expression, increasing the sensitivity of the assay. (ii) A flow cytometric sorting scheme similar to differential fluorescence induction (DFI) (34, 35) was used, in which the first stage of cell sorting includes the collection of induced as well as constitutively expressed clones from the complete metagenomic library, and constitutive clones are removed in subsequent rounds of sorting. This reduced the number of false-positive clones that were collected. (iii) The use of polyethylene glycol (PEG) in a final step of metagenomic DNA purification resulted in significant increases in library size and quality. Using this method, clones related to the metabolism of a full range of LMW AHs were recovered. (iv) Finally, by combining the results of metagenome clone analysis with whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing of a matched DNA sample, we demonstrated that it is possible to map the cloned sequences to larger contigs assembled de novo from the whole metagenome shotgun sequence data. Such a method could be applied to improve predictions regarding the origin and surrounding sequence of short metagenomic clones that possess functional significance suggested by their gene expression or protein activity but for which the full sequence was not recovered. This work therefore presents a significant improvement over traditional methods such as hybridization to bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones to identify the surrounding sequence of small plasmid-based clones, for which reliable alternatives have not yet been suggested.

The aromatic-inducible genes recovered from the Rock Bay metagenome by SIGEX were induced by at least one LMW aromatic compound (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) and were derived from Pseudomonas or closely related genera in Proteobacteria (Table 2). The sequence of each inducible clone showed high similarity to genes that are known components of aromatic metabolic processes, including genes encoding various oxygenases (NA1, SA1, SE2, LB20, LD20, LD23, LE6, LK9, LK13, LK16, LM13, and LN1) and antibiotic resistance or efflux mechanisms (SE12, LA15, LB1, and LB18) and transposons carrying genes associated with aromatic degradation (LC8 and LM13). Cloned sequences encoding metabolic functions, such as salicylate or naphthalene oxygenases, typically contained only partial genes, often the first or second gene downstream from the putative promoter. Upstream of the promoter, oriented in the opposite direction, ORFs were often found to share high similarity to genes for transcription factors that likely respond to inducers and regulate the promoters (i.e., nahR).

The finding that many aromatic catabolic genes were induced strongly by salicylate is consistent with existing studies (43–45). Transcription factors that respond to salicylate and other LMW aromatics have been described extensively in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms (e.g., the LTTR nahR for Pseudomonas putida G7 [46] and the GntR-type regulator narR1 in Rhodococcus opacus R7 [47]). There is a notable absence of sequences derived from Gram-positive organisms in the PAH-E metagenomic clones. Even after expressing the library in B. cereus (see the methods section in the supplemental material), we did not find any inducible clones related to Gram-positive sequences. However, taxonomic analysis of both the NGS data in this study and data from previous 16S rRNA gene studies of the same sample (48) suggests that Rock Bay soil contains a very high proportion of Proteobacteria and very low proportions of Gram-positive bacteria; therefore, it is expected that this particular sample would not yield high numbers of Gram-positive inducible genes. We demonstrated that at least some proportion of the clones recovered in the E. coli host in this study maintain their inducibility with respect to GFP expression following transformation into B. cereus (Fig. 3) and should therefore be recoverable using SIGEX in a B. cereus host. However, the use of B. cereus in this study was disappointing. This may be due to its low transformation efficiency relative that of to E. coli (leading to a library of lower diversity) as well as a marked lack of sensitivity in the SIGEX protocol (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Overall, the sequences of the clones characterized in this study reveal that SIGEX is capable of recovering genes that are functionally related to the chemical used for their induction.

While the literature has focused on the high-throughput nature of FCM and its ability to rapidly analyze millions of clones (14, 15), another substantial advantage, i.e., single-cell analysis of gene expression (34, 49), has often been overlooked. Single-cell analysis improves the detection of differences between populations having unusual distributions of gene expression. For example, populations with an identical mean value may have significantly different population histograms and median values. This is especially important in metagenomic analysis because promoters in an environmental context are sensitive to alterations in effector molecules, as well as overarching global regulator proteins; in fact, most promoters in an environmental context are regulated as part of complex circuits involving several transcription factors (50). This means that individual cells in the population, which may, for instance, exist in different growth phases (i.e., expressing different σ factors), can activate transcription at the same promoter to different degrees (51). This concept is exemplified by the work of Newman and Shapiro (52), who showed that differential gene expression can be modulated by variations in overarching regulatory dynamics within clonal populations of E. coli. These differences can be detected using FCM analysis of gene expression but would not be evident using qPCR or other types of population mean measurement techniques; therefore, SIGEX is sensitive to the induction of gene expression that might be overlooked with other methods of expression profiling.

SIGEX is also limited in several important ways, many of which were previously addressed by de Lorenzo (53). Generally, it is possible that the regulatory proteins or promoters necessary for transcription do not function in E. coli. Furthermore, the substrate of a given pathway is not always the cognate inducer, and this is manifested in our results via the observation that salicylate, a common intermediate and known inducer of aromatic-degrading pathways (43), was the most common and most potent inducer among aromatic-inducible clones. Library sizes can also impose significant constraints, given that hundreds of species are likely present but it is possible to analyze only a fraction of their genomes. Although our library sizes are larger (by approximately 10-fold) than those in the initial SIGEX report (9), they still represent only a small fraction of the total metagenomic sequence present in our soil samples. Although a range of inducible clones was detected using a variety of AHs, HMW compounds such as fluoranthene, pyrene, and phenanthrene did not give rise to inducible clones in any of our screens. The mechanistic reason for this may be that the transcription factors involved in the activation of genes encoding HMW protein-metabolizing enzymes have a distal location relative to the promoters they regulate. This is likely, given the recent insights into the genetic arrangements of PAH-degrading islands such as the phn island (54), where transcriptional factors implicated in the regulation of terminal dioxygenases are located several kilobases downstream of the promoters they putatively act upon. Other factors that may limit the recovery of certain clones using the SIGEX scheme include the necessity of proper directionality (i.e., the inducible promoter must be oriented toward GFP) and the possibility that different levels of regulation may be responsible for expression of the genes of interest (e.g., posttranscriptional regulation such as antisense RNA).

A major limitation imposed by plasmid-based metagenomic screens is that the insert size is often insufficient to determine the original genomic context. In this study, this was overcome by demonstrating that the SIGEX clones can be effectively mapped to contigs derived from shotgun-sequenced metagenomic DNA (Fig. 4). The genes analyzed on these contigs often align to entire operon structures (e.g., contig 3075 aligns to the Pseudomonas plasmid pAK5 salicylate/gentisate-degrading operon) in the GenBank database, demonstrating that it is possible to use NGS to obtain relevant information about upstream and downstream sequences that are not retrieved using SIGEX by itself. We found that de novo assembly of our data set provided a sufficiently large N50 for the purposes of mapping several complete operons. The quality of a metagenome assembly, as measured by the N50, depends mainly on the species diversity present in the sample. Compared to results of other deep sequencing studies on soils (55), we obtained much larger contigs (with a scaffolded N50 of 9.1 kb and ∼2,000 sequences of >26.8 kb). This is attributable to the fact that species richness of the sample was reduced through the aeration and agitation of the contaminated soil in a bioslurry. This process enriched for species capable of degrading the complex mixture of xenobiotics found in the Rock Bay soil.

A high level of similarity was observed between the SIGEX clones and NGS-derived contigs, with an average of >95% nucleotide identity observed between IDBA-UD de novo-assembled contigs and the sequences of SIGEX clones obtained from Sanger sequencing (Table 3). This demonstrates that whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing can produce assemblies that are accurate enough and contain sufficient upstream and downstream sequence to identify the original context of a metagenome fragment obtained through standard cloning procedures. Our confidence in mapping fragments to contigs was bolstered by targeted assembly of NGS reads using PRICE: this procedure limited contig extension to regions hypothesized to be relevant for aromatic metabolism. Clones mapped to contigs of similar size and composition, regardless of the assembly process (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Amid concerns that metagenomic shotgun sequence data may frequently result in misassembled contigs, the fact that our Sanger-sequenced reads of cloned metagenomic restriction fragments match with a high similarity to the assembled short-read Illumina data provides evidence that, with sufficient coverage, whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing can result in valid sequence assemblies.

The results of this study suggest that, despite the lack of duplication of the original SIGEX reports, the method is applicable to metagenomic gene discovery. Furthermore, SIGEX represents a powerful complement to whole-metagenome NGS technologies, since it allows biologically relevant subsets of the metagenome to be targeted computationally by in silico assembly and prediction tools. The annotation of DNA sequences surrounding metagenomic clones could improve the identification of the organisms from which they originate and aid in the characterization of their role within a community of microorganisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alex Wong for commenting on an earlier version of the manuscript and Patrice Smith for allowing us to use her FACSAria II flow cytometer.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03306-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunet-Galmés I, Busquets A, Peña A, Gomila M, Nogales B, García-Valdés E, Lalucat J, Bennasar A, Bosch R. 2012. Complete genome sequence of the naphthalene-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10 (CCUG 29243). J Bacteriol 194:6642–6643. doi: 10.1128/JB.01753-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin F, Torelli S, Le Paslier D, Barbance A, Martin-Laurent F, Bru D, Geremia R, Blake G, Jouanneau Y. 2012. Betaproteobacteria dominance and diversity shifts in the bacterial community of a PAH-contaminated soil exposed to phenanthrene. Environ Pollut 162:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin F, Malagnoux L, Violet F, Jakoncic J, Jouanneau Y. 2013. Diversity and catalytic potential of PAH-specific ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases from a hydrocarbon-contaminated soil. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:5125–5135. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekkers DM, Cretoiu MS, Kielak AM, Elsas, van Elsas JD. 2012. The great screen anomaly—a new frontier in product discovery through functional metagenomics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 93:1005–1020. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3804-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yergeau E, Sanschagrin S, Beaumier D, Greer CW. 2012. Metagenomic analysis of the bioremediation of diesel-contaminated Canadian high arctic soils. PLoS One 7:e30058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yergeau E, Arbour M, Brousseau R, Juck D, Lawrence JR, Masson L, Whyte LG, Greer CW. 2009. Microarray and real-time PCR analyses of the responses of high-arctic soil bacteria to hydrocarbon pollution and bioremediation treatments. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:6258–6267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01029-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lämmle K, Zipper H, Breuer M, Hauer B, Buta C, Brunner H, Rupp S. 2007. Identification of novel enzymes with different hydrolytic activities by metagenome expression cloning. J Biotechnol 127:575–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones MD, Crandell DW, Singleton DR, Aitken MD. 2011. Stable-isotope probing of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial guild in a contaminated soil. Environ Microbiol 13:2623–2632. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchiyama T, Abe T, Ikemura T, Watanabe K. 2005. Substrate-induced gene-expression screening of environmental metagenome libraries for isolation of catabolic genes. Nat Biotechnol 23:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nbt1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchiyama T, Watanabe K. 2008. Substrate-induced gene expression (SIGEX) screening of metagenome libraries. Nat Protoc 3:1202–1212. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchiyama T, Watanabe K. 2007. The SIGEX scheme: high throughput screening of environmental metagenomes for the isolation of novel catabolic genes. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev 24:107–116. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2007.10648094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchiyama T, Miyazaki K. 2010. Substrate-induced gene expression screening: a method for high-throughput screening of metagenome libraries. Methods Mol Biol 668:153–168. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-823-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yun J, Ryu S. 2005. Screening for novel enzymes from metagenome and SIGEX, as a way to improve it. Microb Cell Fact 4:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handelsman J. 2005. Sorting out metagenomes. Nat Biotechnol 23:38–39. doi: 10.1038/nbt0105-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taupp M, Mewis K, Hallam SJ. 2011. The art and design of functional metagenomic screens. Curr Opin Biotechnol 22:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumtaz M, George J. 1995. Toxicological profile for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundstedt S, White PA, Lemieux CL, Lynes KD, Lambert IB, Oberg L, Haglund P, Tysklind M. 2007. Sources, fate, and toxic hazards of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) at PAH-contaminated sites. Ambio 36:475–485. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[475:SFATHO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemieux CL, Lambert IB, Lundstedt S, Tysklind M, White PA. 2008. Mutagenic hazards of complex polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures in contaminated soil. Environ Toxicol Chem 27:978–990. doi: 10.1897/07-157.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanaly RA, Harayama S. 2000. Biodegradation of high-molecular-weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by bacteria. J Bacteriol 182:2059–2067. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.8.2059-2067.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haritash AK, Kaushik CP. 2009. Biodegradation aspects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): a review. J Hazard Mater 169:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBruyn JM, Mead TJ, Sayler GS. 2012. Horizontal transfer of PAH catabolism genes in Mycobacterium: evidence from comparative genomics and isolated pyrene-degrading bacteria. Environ Sci Technol 46:99–106. doi: 10.1021/es201607y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng R-H, Xiong A-S, Xue Y, Fu X-Y, Gao F, Zhao W, Tian Y-S, Yao Q-H. 2008. Microbial biodegradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:927–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labana S, Kapur M, Malik DK, Prakash D, Jain R. 2007. Diversity, biodegradation and bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, p 409–443. In Singh SN, Tripathi RD (ed), Environmental bioremediation technologies. Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinyakong O, Habe H, Omori T. 2003. The unique aromatic catabolic genes in sphingomonads degrading polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). J Gen Appl Microbiol 49:1–19. doi: 10.2323/jgam.49.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S-J, Kweon O, Jones RC, Freeman JP, Edmondson RD, Cerniglia CE. 2007. Complete and integrated pyrene degradation pathway in Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1 based on systems biology. J Bacteriol 189:464–472. doi: 10.1128/JB.01310-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vartoukian SR, Palmer RM, Wade WG. 2010. Strategies for culture of “unculturable” bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 309:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S-J, Kweon O, Cerniglia CE. 2009. Proteomic applications to elucidate bacterial aromatic hydrocarbon metabolic pathways. Curr Opin Microbiol 12:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kweon O, Kim S-J, Freeman JP, Song J, Baek S, Cerniglia CE. 2010. Substrate specificity and structural characteristics of the novel Rieske nonheme iron aromatic ring-hydroxylating oxygenases NidAB and NidA3B3 from Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1. mBio 1:e00135-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00135-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singleton DR, Hu J, Aitken MD. 2012. Heterologous expression of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase genes from a novel pyrene-degrading betaproteobacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:3552–3559. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00173-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn AK, Handelsman J. 1999. A vector for promoter trapping in Bacillus cereus. Gene 226:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whynot C. 2009. The efficacy of different bioremediation strategies in removing mutagenic hazard from contaminated soil. M.S. thesis Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shapiro HM. 2003. Practical flow cytometry. Wiley-Liss, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rediers H, Rainey PB, Vanderleyden J, De Mot R. 2005. Unraveling the secret lives of bacteria: use of in vivo expression technology and differential fluorescence induction promoter traps as tools for exploring niche-specific gene expression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69:217–261. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.217-261.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pothier JF, Wisniewski-Dyé F, Weiss-Gayet M, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Prigent-Combaret C. 2007. Promoter-trap identification of wheat seed extract-induced genes in the plant-growth-promoting rhizobacterium Azospirillum brasilense Sp245. Microbiology 153:3608–3622. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer F, Paarmann D, D'Souza M, Olson R, Glass EM, Kubal M, Paczian T, Rodriguez A, Stevens R, Wilke A, Wilkening J, Edwards RA. 2008. The metagenomics RAST server—a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 9:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, Chin FYL. 2012. IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics 28:1420–1428. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruby JG, Bellare P, Derisi JL. 2013. PRICE: software for the targeted assembly of components of (meta) genomic sequence data. G3 3:865–880. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.005967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmeisser C, Steele H, Streit WR. 2007. Metagenomics, biotechnology with non-culturable microbes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 75:955–962. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0945-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu W, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. 2010. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 38:e132. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park HH, Lee HY, Lim WK, Shin HJ. 2005. NahR: effects of replacements at Asn 169 and Arg 248 on promoter binding and inducer recognition. Arch Biochem Biophys 434:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gottfried A, Singhal N, Elliot R, Swift S. 2010. The role of salicylate and biosurfactant in inducing phenanthrene degradation in batch soil slurries. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86:1563–1571. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lönneborg R, Brzezinski P. 2011. Factors that influence the response of the LysR type transcriptional regulators to aromatic compounds. BMC Biochem 12:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park W, Padmanabhan P, Padmanabhan S, Zylstra GJ, Madsen EL. 2002. nahR, encoding a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, is highly conserved among naphthalene-degrading bacteria isolated from a coal tar waste-contaminated site and in extracted community DNA. Microbiology 148:2319–2329. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-8-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Gennaro P, Terreni P, Masi G, Botti S, De Ferra F, Bestetti G. 2010. Identification and characterization of genes involved in naphthalene degradation in Rhodococcus opacus R7. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87:297–308. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose CG. 2010. Temporal changes in the microbial community of a PAH-contaminated soil during bench-top bioremediation. M.S. thesis University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hermans K, Nguyen TLA, Roberfroid S, Schoofs G, Verhoeven T, De Coster D, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SCJ. 2011. Gene expression analysis of monospecies Salmonella typhimurium biofilms using differential fluorescence induction. J Microbiol Methods 84:467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cases I, de Lorenzo V. 2005. Promoters in the environment: transcriptional regulation in its natural context. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:105–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Las Heras A, Fraile S, de Lorenzo V. 2012. Increasing signal specificity of the TOL network of pseudomonas putida mt-2 by rewiring the connectivity of the master regulator XylR. PLoS Genet 8:e1002963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newman DL, Shapiro JA. 1999. Differential fiu-lacZ fusion regulation linked to Escherichia coli colony development. Mol Microbiol 33:18–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Lorenzo V. 2005. Problems with metagenomic screening. Nat Biotechnol 23:1045 (Author reply, 23:1045–1046.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hickey WJ, Chen S, Zhao J. 2012. The phn island: a new genomic island encoding catabolism of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. Front Microbiol 3:125. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delmont TO, Simonet P, Vogel TM. 2012. Describing microbial communities and performing global comparisons in the 'omic era. ISME J 6:1625–1628. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James KD, Williams PA. 1998. ntn genes determining the early steps in the divergent catabolism of 4-nitrotoluene and toluene in Pseudomonas sp. strain TW3. J Bacteriol 180:2043–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li W, Shi J, Wang X, Han Y, Tong W, Ma L, Liu B, Cai B. 2004. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the naphthalene catabolic plasmid pND6-1 from Pseudomonas sp. strain ND6. Gene 336:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin RG, Jair KW, Wolf RE, Rosner JL. 1996. Autoactivation of the marRAB multiple antibiotic resistance operon by the MarA transcriptional activator in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 178:2216–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roldan MD, Perez-Reinado E, Castillo F, Moreno-Vivian C. 2008. Reduction of polynitroaromatic compounds: the bacterial nitroreductases. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:474–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bosch R, Moore ER, García-Valdés E, Pieper DH. 1999. NahW, a novel, inducible salicylate hydroxylase involved in mineralization of naphthalene by Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10. J Bacteriol 181:2315–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heinaru E, Vedler E, Jutkina J, Aava M, Heinaru A. 2009. Conjugal transfer and mobilization capacity of the completely sequenced naphthalene plasmid pNAH20 from multiplasmid strain Pseudomonas fluorescens PC20. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 70:563–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watanabe T, Fujihara H, Furukawa K. 2003. Characterization of the second LysR-type regulator in the biphenyl-catabolic gene cluster of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J Bacteriol 185:3575–3582. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.12.3575-3582.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujihara H, Yoshida H, Matsunaga T, Goto M, Furukawa K. 2006. Cross-regulation of biphenyl- and salicylate-catabolic genes by two regulatory systems in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J Bacteriol 188:4690–4697. doi: 10.1128/JB.00329-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harwood CS, Parales RE. 1996. The beta-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol 50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nishi A, Tominaga K, Furukawa K. 2000. A 90-kilobase conjugative chromosomal element coding for biphenyl and salicylate catabolism in Pseudomonas putida KF715. J Bacteriol 182:1949–1955. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.7.1949-1955.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stewart V, Parales J. 1988. Identification and expression of genes narL and narX of the nar (nitrate reductase) locus in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 170:1589–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rabin RS, Stewart V. 1992. Either of two functionally redundant sensor proteins, NarX and NarQ, is sufficient for nitrate regulation in Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:8419–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lambert IB, Carroll C, Laycock N, Koziarz J, Lawford I, Duval L, Turner G, Booth R, Douville S, Whiteway J, Nokhbeh MR. 2001. Cellular determinants of the mutational specificity of 1-nitroso-6-nitropyrene and 1-nitroso-8-nitropyrene in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. Mutat Res 484:19–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich SD. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 144(Pt 11):3097–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.