Abstract

MvaT proteins are members of the H-NS family of proteins in pseudomonads. The IncP-7 conjugative plasmid pCAR1 carries an mvaT-homologous gene, pmr. In Pseudomonas putida KT2440 bearing pCAR1, pmr and the chromosomally carried homologous genes, turA and turB, are transcribed at high levels, and Pmr interacts with TurA and TurB in vitro. In the present study, we clarified how the three MvaT proteins regulate the transcriptome of P. putida KT2440(pCAR1). Analyses performed by a modified chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with microarray technology (ChIP-chip) suggested that the binding regions of Pmr, TurA, and TurB in the P. putida KT2440(pCAR1) genome are almost identical; nevertheless, transcriptomic analyses using mutants with deletions of the genes encoding the MvaT proteins during the log and early stationary growth phases clearly suggested that their regulons were different. Indeed, significant regulon dissimilarity was found between Pmr and the other two proteins. Transcription of a larger number of genes was affected by Pmr deletion during early stationary phase than during log phase, suggesting that Pmr ameliorates the effects of pCAR1 on host fitness more effectively during the early stationary phase. Alternatively, the similarity of the TurA and TurB regulons implied that they might play complementary roles as global transcriptional regulators in response to plasmid carriage.

INTRODUCTION

The nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) of bacteria are recognized as global regulators of gene expression (1, 2). Histone-like protein H1 (H-NS) is one of the most abundant NAPs in Gram-negative bacteria, such as the genera Escherichia and Salmonella (3). H-NS can affect DNA topology by binding to specific loci to cause condensation of chromosomal DNA, thereby regulating gene expression (4). MvaT proteins in Pseudomonas spp. are recognized as members of the H-NS family because they can complement Escherichia coli H-NS-deficient phenotypes (5–9). H-NS and MvaT homologs share similar characteristics (e.g., dimerization, oligomerization, and DNA-binding mechanisms) (6–8), although the regions important for homo-oligomerization and DNA sequence preference are different (9, 10). Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (11) possesses five genes encoding MvaT proteins, designated turA (PP_1366), turB (PP_3765), turC (PP_0017), turD (PP_3693), and turE (PP_2947) (12). TurA and TurB were originally copurified as transcriptional repressors of the TOL plasmid upper operon (13), which regulates a large number of genes in KT2440 (12).

Interestingly, genes encoding H-NS family proteins are also found in conjugative plasmids (14–16), and their products have a stealth function by silencing transcriptional perturbation of the host chromosome with minimal effects on host fitness (17, 18). The IncP-7 carbazole-degradative plasmid pCAR1 was isolated from Pseudomonas resinovorans CA10 (19) and has been sequenced fully and found to carry an mvaT-homologous gene, pmr. Transcriptomic analysis of KT2440 harboring pCAR1 [KT2440(pCAR1)] (20) revealed that Pmr is a key transcriptional regulator of genes in both pCAR1 and the host cell chromosome (18). Genome-wide analysis of the DNA-binding regions of Pmr in KT2440(pCAR1) was performed by chromatin affinity purification coupled with a high-density tiling chip (ChAP-chip) (a modification of chromatin immunoprecipitation with microarray technology [ChIP-chip]) and showed that this protein binds preferentially to horizontally acquired DNA regions (18). Among six MvaT-encoding genes in KT2440(pCAR1), pmr, turA, and turB are transcribed at high levels, and Pmr can interact with TurA and TurB in vitro (18). Therefore, these three MvaT proteins may cooperatively regulate the expression of both chromosomal and plasmid genes in KT2440(pCAR1) by binding to chromosomal and plasmid DNAs.

In this study, the DNA-binding regions of Pmr, TurA, and TurB in the KT2440(pCAR1) genome were identified by ChAP-chip analyses. Transcriptomic analyses were then conducted by a tiling array assay using deletion mutants of the MvaT-encoding genes in cells during the log (L) and early stationary (ES) growth phases. Based on the results, we discuss how these three MvaT proteins encoded on pCAR1 and the host chromosome regulate transcriptional networks in KT2440(pCAR1) cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Pseudomonas putida KT2440(pCAR1) and its derivatives were cultivated in L broth (LB) (22) at 30°C, and Escherichia coli DH5α (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) and S17-1 λpir (21), used for construction of the derivative strains, were grown in LB at 37°C or 30°C. Ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and/or gentamicin (120 μg/ml) was added to the medium. For plate cultures, the medium was solidified using 1.6% (wt/vol) agar. For culture using succinate as the sole carbon source, overnight cultures of KT2440(pCAR1) and its derivatives in LB at 30°C were inoculated into 100 ml NMM-4 (23) supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) succinate to obtain an initial turbidity at 600 nm of 0.05 and then were incubated at 30°C in a rotating shaker at 120 rpm for 4 h (L phase; turbidity at 600 nm of 0.15 to 0.25) or 8 h (ES phase; turbidity at 600 nm of 0.35 to 0.4).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) deoR thi-1 supE44 λ gyrA96 relA1 | Toyobo |

| S17-1 λpir | RK2 tra regulon; host for pir-dependent plasmids; recA thi pro ΔhsdR M+ RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 λpir Tpr Smr | 21 |

| P. putida strains | ||

| KT2440 | Naturally Cmr | 11 |

| KT2440(pCAR1) | KT2440 harboring pCAR1 | 20 |

| KT2440(pCAR1 pmrHis) | KT2440(pCAR1) carrying gene encoding 6×His-tagged Pmr | 18 |

| KT2440 turAHis(pCAR1) | KT2440(pCAR1) carrying gene encoding 6×His-tagged TurA | This study |

| KT2440 turBHis(pCAR1) | KT2440(pCAR1) carrying gene encoding 6×His-tagged TurB | This study |

| KT2440(pCAR1 Δpmr) | KT2440(pCAR1) single-deletion mutant lacking pmr gene | 30 |

| KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1) | KT2440(pCAR1) single-deletion mutant lacking turA gene | This study |

| KT2440 ΔturB(pCAR1) | KT2440(pCAR1) single-deletion mutant lacking turB gene | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pT7Blue T-vector | Used for cloning of PCR products; Apr lacZα | Merck Millipore |

| pPS856 | Template for PCR amplification of Gmr gene flanked by FRT sites | 24 |

| pFLP2Km | Flp recombinase expression vector for removal of Gmr gene; Kmr ori1600 oriT(RP4) | 18 |

| pK19mobsacB | Suicide vector; Kmr oriT(RP4) sacB lacZα; pMB1 replicon | 25 |

| pK19mobsacBΔturA | pK19mobsacB containing 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of turA and the Gmr gene flanked by FRT sites | This study |

| pK19mobsacBΔturB | pK19mobsacB containing 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of turB and the Gmr gene flanked by FRT sites | This study |

| pK19mobsacBTurA_His | pK19mobsacB containing 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of turA, a gene encoding TurA with 6×His at its C-terminal end, and the Gmr gene flanked by FRT sites | This study |

| pK19mobsacBTurB_His | pK19mobsacB containing 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of turB, a gene encoding TurB with 6×His at its C-terminal end, and the Gmr gene flanked by FRT sites | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Plasmids used for construction of the KT2440(pCAR1) derivatives (pT7Blue T-vector [Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA], pPS856 [24], pFLP2Km [18], pK19mobsacB [25], and their derivatives) were extracted from E. coli by using the alkaline lysis method (22). Total DNAs from Pseudomonas strains were extracted using hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide as described previously (26). PCR was performed using KOD-Plus polymerase (Toyobo) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragments were extracted from agarose gels by using an EZNA gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA) and were ligated to the appropriate vector by using Ligation High reagent (Toyobo). The primers used for construction of the strains are listed in Table 2 (for detailed information regarding strain construction, see Text S1 in the supplemental material). All other procedures were performed according to standard methods (22).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Note | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP1366-Del01-F | CCCAAGCTTGGATGTTCGATGAT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturA | This study |

| PP1366-Del02-Gm-R | TTTGAAGCTAATTCGTTATCCGCATACGCC | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturA | This study |

| PP1366-Del03-Gm-F | AAGATCCCCAATTCGGGAGTGTTCCTTAAT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturA | This study |

| PP1366-Del04-R | CGGGATCCACGGTCGGGGCAGGC | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturA | This study |

| PP3765-Del01-F | CCCAAGCTTAACAACCTGTGGCA | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturB | This study |

| PP3765-Del02-Gm-R | TTTGAAGCTAATTCGTGTAATCACTCCTGT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturB | This study |

| PP3765-Del03-Gm-F | AAGATCCCCAATTCGTGAAATGCCCACATA | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturB | This study |

| PP3765-Del04-R | CGGGATCCACTTCTCGATGTCCT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBΔturB | This study |

| PP1366-His01 | CCCAAGCTTACAATTGGCCAATCAACA | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurA_His | This study |

| PP1366-His02 | TTTGAAGCTAATTCGTTATCCGCATACGCC | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurA_His | This study |

| PP1366-His03 | GATCCCCAATTCGTCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGTCCAGCAGGGTT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurA_His | This study |

| PP1366-His04 | CGGGATCCCTATTCTAGCGGTCCGCC | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurA_His | This study |

| PP3765-His01 | CCCAAGCTTCCATTGGACCATGGTCTA | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurB_His | This study |

| PP3765-His02 | TGAAGCTAATTCGTCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGCGTACCCAGCTT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurB_His | This study |

| PP3765-His03 | AAGATCCCCAATTCGTGAAATGCCCACATA | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurB_His | This study |

| PP3765-His04 | CGGGATCCGGATCGACTTCATCCACT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacBTurB_His | This study |

| Gm-F | CGAATTAGCTTCAAAAGCGCTCTGA | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacB | 27 |

| Gm-R | CGAATTGGGGATCTTGAAGTTCCT | Used to amplify insert region of pK19mobsacB | 27 |

Artificial restriction sites are underlined.

Preparation of KT2440(pCAR1) derivatives and ChAP-chip analysis.

A KT2440(pCAR1) derivative strain in which the pmr gene was replaced with a gene encoding a C-terminally six-histidine (His)-tagged Pmr protein was constructed and subjected to ChAP-chip analysis in a previous study (18). In the present study, KT2440(pCAR1) derivative strains expressing His-tagged TurA or TurB were prepared similarly, using a homologous recombination-based unmarked gene replacement system (27).

ChAP-chip analysis was performed as described previously (18), except that formaldehyde-treated cells were sonicated using a Bioruptor water bath sonication system (Cosmo Bio Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, both DNA fractions that were affinity purified with each MvaT protein (“treatment”) and those isolated from the whole-cell extract before purification (“control”) were hybridized separately to a custom tiling array which contained 25-mer probes designed to cover both strands on the whole genome of the KT2440 chromosome (11-bp offset) and pCAR1 (9-bp offset) (28, 29). The probability of binding (P value) of each probe was computed using Affymetrix tiling analysis software v1.1 (TAS; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) to examine biologically duplicated data with a window of ±300 bp, which means that every probe in the 601-bp region was included in the calculation of the P value for one probe. The regions for which the P values were <10−15 were identified as protein-binding regions.

Preparation of gene deletion mutants and tiling array transcriptomic analyses of pCAR1 and the KT2440 chromosome.

A markerless deletion mutant of pmr was constructed previously (30). In the present study, each single-gene deletion mutant of turA and turB was prepared similarly from KT2440(pCAR1) by using a homologous recombination-based unmarked gene replacement system (27) as described previously. RNAs were extracted from Pseudomonas strains grown to the L or ES phase as described previously (31), with the exception that not only a Nucleospin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany) but also an RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen) was used. Transcriptomic analyses based on the tiling arrays were performed using total RNA extracted from 1 × 109 cells during the L or ES growth phase as described previously (28, 29). It should be noted that cDNA was synthesized in the presence of actinomycin D to prevent the generation of spurious second-strand cDNA (31, 32). We used the same custom tiling array as that used for ChAP-chip. The signal intensity for each probe was computed using TAS, with a window of ±30 bp. The intensities were linearly scaled so that the median was 100. For the transcriptional value of each coding DNA sequence (CDS), the median signal intensities of the probes located within each CDS were calculated using R software (https://www.r-project.org/) as described previously (28). CDSs with values of >64 were defined as transcribed genes. Among the transcribed genes, we identified those with transcription value ratios between two strains of >2.0 (e.g., the wild-type strain and a deletion mutant) as differentially transcribed genes.

Microarray data accession number.

The array data reported in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under GEO Series accession no. GSE72639.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genome-wide analyses of Pmr-, TurA-, and TurB-binding regions.

To compare the binding regions of the three MvaT proteins, we performed ChAP-chip analyses of the KT2440 chromosome and of pCAR1 during L phase. Because Pmr, TurA, and TurB have highly identical amino acid sequences (50 to 60% identity) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), we did not have antibodies which show no cross-reactivity among these three proteins. Thus, we decided to use KT2440(pCAR1) derivatives expressing C-terminally His-tagged forms of Pmr, TurA, and TurB instead of the corresponding intact forms. It should be noted that the C-terminal His tags were not likely to affect DNA-binding ability or the sequence preference of the three proteins, because the C terminus of MvaT is not involved in DNA binding (10). Although the genome-wide Pmr-binding regions were determined previously (18), we again obtained the ChAP-chip data on Pmr-binding regions accompanied by those on TurA- and TurB-binding regions, because in this study we modified the method of ChAP-chip analysis to incorporate a different sonication system.

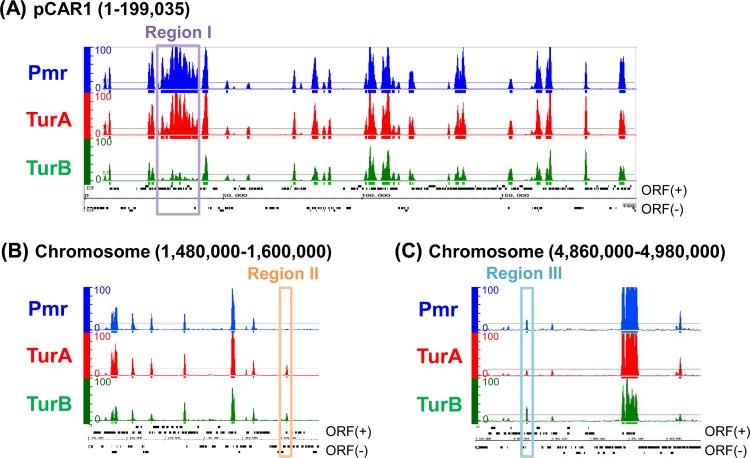

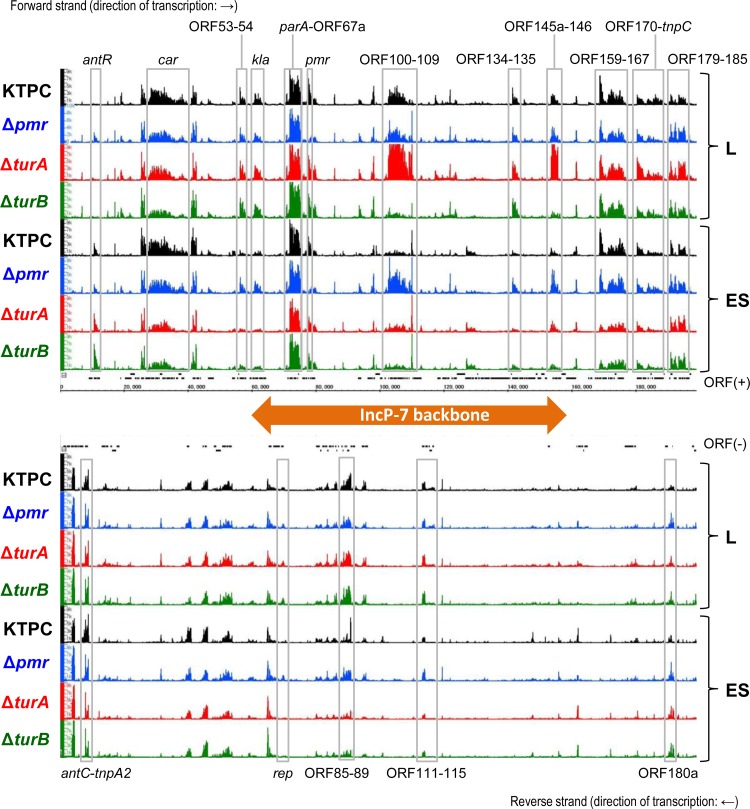

(i) Heteromeric oligomers of Pmr, TurA, and TurB form at almost all binding regions of both the pCAR1 plasmid and the KT2440 chromosome.

Among the three MvaT proteins, the P value distribution patterns were almost identical for both the KT2440 chromosome and the pCAR1 plasmid (Fig. 1; see Tables S1 to S6 in the supplemental material). Binding of the three proteins (P < 10−15) was detected at 245 (Pmr), 267 (TurA), and 263 (TurB) regions of the KT2440 chromosome and at 24 (Pmr), 34 (TurA), and 29 (TurB) regions of pCAR1 (see Tables S1 to S6). The positions overlapped each other: 90.3% (Pmr), 88.2% (TurA), and 94.0% (TurB) of the total lengths of binding regions on the chromosome and 92.4% (Pmr), 91.3% (TurA), and 94.6% (TurB) of those on pCAR1 overlapped the previously reported Pmr-binding regions (18) (see Tables S1 to S6).

FIG 1.

Distribution of P values and putative binding regions of the three MvaT proteins on pCAR1 (A) and the P. putida KT2440 chromosome (B and C). Blue, red, and green bars represent the −10 log10(P value) values for each probe determined by ChAP-chip analyses of KT2440(pCAR1) expressing Pmr, TurA, and TurB, respectively. Colored horizontal lines indicate a P value of 10−15, and putative binding regions of each H-NS family protein are shown by colored rectangles. Black rectangles indicate the locations of annotated open reading frames (ORFs) which are transcribed from left to right (above) and from right to left (below). Purple, orange, and light blue boxes indicate the regions for which the P value for one MvaT protein was markedly different from those for the other two MvaT proteins.

Considering that all three MvaT proteins have both a DNA-binding domain and a dimerization/oligomerization domain and that homodimers of each protein interact with homodimers of the others or itself (8, 18), heteromeric oligomers consisting of each homodimer of the three proteins (i.e., heteromeric oligomers cannot be defined as dimers, trimers, or tetramers, as the number and the ratio of each homodimer would vary) may have formed on chromosomal and plasmid DNAs. Because our ChAP-chip analyses involved affinity purification of His-tagged MvaT proteins cross-linked chemically with DNA and other proteins, the DNA-binding regions of each homo-oligomer as well as those of heteromeric oligomers could be detected.

(ii) The three MvaT proteins preferentially bind to low-G+C regions.

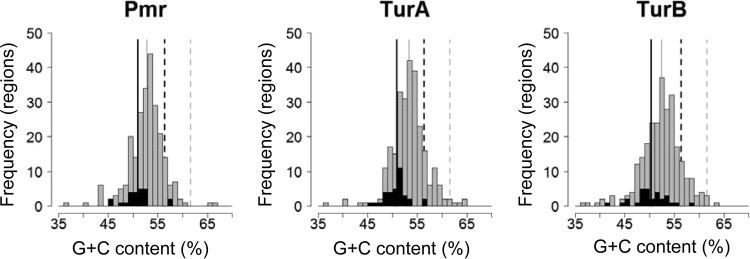

H-NS family proteins, including MvaT proteins, preferentially bind to low-G+C regions of the genome (3). Thus, we calculated the G+C contents of the identified binding regions. The average G+C contents of the 245 Pmr-binding regions (52.7% ± 3.5%), the 267 TurA-binding regions (53.3% ± 3.5%), and the 263 TurB-binding regions (52.4% ± 4.0%) on the chromosome were significantly lower than that of the entire KT2440 chromosome (61.6%) (Fig. 2). The 24 Pmr-binding regions, 34 TurA-binding regions, and 29 TurB-binding regions on pCAR1 also exhibited lower average G+C contents (50.9% ± 2.8%, 50.8% ± 2.4%, and 50.3% ± 3.4%, respectively) than that of the entire pCAR1 plasmid (56.3%) (Fig. 2). That is, the three MvaT proteins preferentially bind to low-G+C regions both on the KT2440 chromosome and on pCAR1. Based on the CDS data for KT2440 and pCAR1, we also calculated the G+C contents of the intragenic and intergenic regions (see Text S1 and Table S7 in the supplemental material). The G+C contents of intergenic regions were significantly lower than those of intragenic regions, and the three MvaT proteins preferentially bound to the intergenic regions both on KT2440 and on pCAR1 (see Text S1 and Table S7).

FIG 2.

Distribution of G+C contents of Pmr-, TurA-, and TurB-binding regions in the KT2440 chromosome (gray bars) and the pCAR1 plasmid (black bars). Average G+C contents in the binding regions for the three H-NS family proteins in the chromosome and in pCAR1 are shown by gray and black solid lines, respectively. Average G+C contents in the entire chromosome and pCAR1 are shown by gray and black dashed lines, respectively.

(iii) TurB is less abundant than TurA and Pmr in heteromeric oligomers.

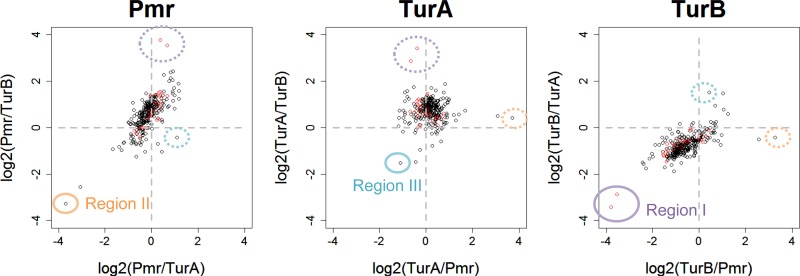

It is noteworthy that the P value (probability) for TurB binding was markedly lower than that for Pmr or TurA binding among most identified MvaT protein-binding regions, both on the pCAR1 plasmid and on the KT2440 chromosome (Fig. 1). Although the P value peak height in Fig. 1 might not necessarily be correlated with the binding region occupancy of the proteins as reported previously (33), we tried to compare these P values quantitatively. We defined “union-binding regions” at which the P value of at least one of the three MvaT proteins was <10−15 (see Tables S8 and S9 in the supplemental material) and calculated the P value ratio for each region (Fig. 3). Scatterplots showed that the distribution patterns of union-binding regions on the chromosome (the relationships among the P values for Pmr, TurA, and TurB) were similar to those on pCAR1. In addition, the P values for TurB binding were lower than those for Pmr and TurA binding (most were located in the third quadrant of the scatterplots for TurB-binding regions). These results suggest that fewer TurB proteins exist in the heteromeric oligomers formed in the binding regions. There are five possible reasons for this: (i) a lower level of TurB than Pmr or TurA in the cell; (ii) slight differences in DNA-binding domain sequence preference among the three MvaT proteins and a small number of TurB-preferred DNA sequence regions; (iii) a potentially lower DNA-binding strength of TurB than of Pmr and TurA, if the differences in the preferred binding sequences among the three MvaT proteins are negligible; (iv) a potentially lower affinity of TurB for other MvaT proteins, in terms of heteromeric oligomer formation, than those of Pmr and TurA, if the sequence preferences and DNA-binding strengths of the three MvaT proteins are nearly equivalent; and (v) the His tag in each protein might be affected by the accessibility of TurB-DNA complexes with the other complexes. For possibility i, although the levels of the three MvaT proteins in KT2440(pCAR1) cells have not been quantified, the transcription levels were reported to be lower for turB than for pmr and turA in an RNA map of KT2440(pCAR1) during L-phase growth under identical culture conditions (18, 31). Regarding possibility iv, the coupling ratio of TurB-Pmr was found to be lower than those of Pmr-Pmr and TurA-Pmr (9). Recently, Ding and colleagues identified the important residues for DNA binding in MvaT of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (10). Considering that these residues are completely conserved in TurA but not in Pmr or TurB (see Fig. S1), it is possible that the three MvaT proteins have different sequence preferences or DNA-binding strengths, as mentioned in possibilities ii and iii.

FIG 3.

Scatterplots of P value ratios for each union-binding region. “Log2(Pmr/TurA)” indicates the log2 (P value for Pmr binding divided by P value for TurA binding), for example. Black and red open circles indicate union-binding regions in the chromosome (284 regions) and pCAR1 (24 regions), respectively. Regions I to III, from which the circled plots were derived, are shown in Fig. 1.

(iv) Contents of the three MvaT proteins in heteromeric oligomers.

The data in Fig. 3 also suggest that the ratios between P values were not constant. For example, as shown in Fig. 1A, the P value for TurB was low for region I on pCAR1, which includes carbazole degradation genes. This result suggested that the ratios of TurB are not equivalent among all binding regions and that inclusion of TurB in MvaT protein oligomers formed in the corresponding region is difficult. Variations in the ratio between P values were also found for the chromosome and for Pmr and TurA (Fig. 3). For example, the P value for Pmr was relatively low for region II (Fig. 1B), and that for TurA was relatively low for region III (Fig. 1C). Similar results were also detected in pCAR1 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and these results suggested that the contents of the individual MvaT proteins in heteromeric oligomers vary among binding regions.

Transcriptomic comparisons of KT2440(pCAR1) deletion mutants of the genes encoding the three MvaT proteins.

Transcriptomic comparisons were performed between the wild-type strain KT2440(pCAR1) and deletion mutants of the genes encoding the MvaT proteins (pmr, turA, and turB). The transcriptomic analyses were conducted using cells collected during the L and ES growth phases. Our previous transcriptomic data on KT2440 and KT2440(pCAR1) (31) were used to compare the effects of pCAR1 carriage and deletion of each MvaT-encoding gene in KT2440(pCAR1) on transcription of CDSs both on chromosomes and on plasmids.

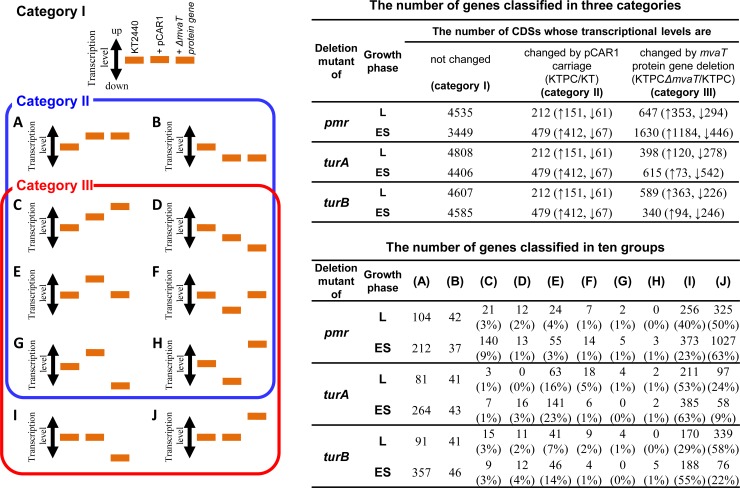

(i) Markerless deletion of turA, turB, or pmr exerts greater effects on the host transcriptome than does pCAR1 carriage.

Of the total of 5,350 CDSs on the KT2440 chromosome, 22 could not be detected by our custom tiling array (see Table S9 in the supplemental material) because no probe was available (28). The 5,328 CDSs detected were divided into 11 groups and 3 categories based on their transcriptional patterns (Fig. 4). The CDSs whose transcript levels were not affected by pCAR1 carriage or by any gene deletion (category I) were excluded from further analyses (Fig. 4). The remaining CDSs were classified into groups A to J (Fig. 4). The CDSs whose transcript levels were affected by pCAR1 carriage were included in groups A to H (category II), whereas those affected by deletion of each MvaT-encoding gene were included in groups C to J (category III). In our previous transcriptomic analysis of L-phase cells, using only a pmr disruption mutant containing a Gmr gene cassette (18), the number of CDSs in category III (159 within the chromosome) was greater than that in category II (112 genes). In the present study, with the exception of the effect of turB deletion during the ES phase, the number of CDSs in category III was also greater than that in category II (Fig. 4), suggesting that not only for Pmr but also for TurA and TurB, the effect of deletion of each gene was greater than that of pCAR1 carriage itself. It should be noted that >70% of category III CDSs were included in groups I and J (Fig. 4). The transcript levels of the genes in groups I and J were not affected by the carriage of intact pCAR1 but were influenced markedly by deletion of each of the MvaT-encoding genes. Although we previously reported such a deflection of differentially transcribed genes into groups I and J (18), the results of this study showed that the number of differentially transcribed genes in group J for KT2440(pCAR1 Δpmr) during the ES phase was considerably larger than that for the other mutants. This was supported by detailed comparisons of the differentially transcribed genes caused by deletion of the three MvaT-encoding genes (see Text S1 and Tables S10 and S11). This finding suggested that all three MvaT proteins may be involved in mediating host adaptation to plasmid carriage and that plasmid-encoded Pmr plays a central role, which is the known stealth function of H-NS proteins encoded by plasmids in Salmonella (17).

FIG 4.

Classification of CDSs differentially transcribed due to pCAR1 carriage and/or markerless deletion of pmr, turA, or turB. Each bar indicates the relative transcription level in KT2440 (KT), KT2440(pCAR1) (KTPC), or an mvaT gene (pmr, turA, or turB) deletion mutant (KTPCΔmvaT). ↑ and ↓, upregulated and downregulated CDSs, respectively.

(ii) Differences in the TurA, TurB, and Pmr regulons in KT2440(pCAR1).

In this study, we defined the regulons of the MvaT proteins as genes whose transcription was affected by deletion of the proteins. To compare the regulons of the three MvaT proteins, a comparison of host transcriptomes was performed between KT2440(pCAR1) and each deletion mutant. KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1) altered the transcript levels of 398 (120 upregulated and 278 downregulated) and 615 (73 upregulated and 542 downregulated) CDSs on the KT2440 chromosome during the L and ES phases, respectively, in comparison to those of KT2440(pCAR1) (Fig. 5; see Table S10 in the supplemental material). KT2440 ΔturB(pCAR1) altered the transcript levels of 589 (L phase; 363 upregulated and 226 downregulated) and 340 (ES phase; 94 upregulated and 246 downregulated) CDSs on the KT2440 chromosome, while KT2440(pCAR1 Δpmr) altered those of 647 (L phase; 353 upregulated and 294 downregulated) and 1,630 (ES phase; 1,184 upregulated and 446 downregulated) CDSs on the KT2440 chromosome (Fig. 5; see Table S10). The sum of the upregulated and downregulated CDSs in comparison to that for strain KT2440(pCAR1) caused by deletion of each MvaT-encoding gene was considered the regulon of the corresponding MvaT protein. Notably, the regulons of the three MvaT proteins differed (Fig. 5), although heteromeric oligomers of Pmr, TurA, and TurB formed at almost all of the putative DNA-binding regions, as mentioned above (Fig. 1). Of the CDSs of the Pmr regulon, 58.7% and 79.2% were not included in the regulons of the other two MvaT proteins during the L and ES phases, respectively (Fig. 5). In other words, the expression of those genes was regulated by Pmr independently of the other two MvaT proteins. The ratio of independently regulated genes in the Pmr regulon was higher than those for the TurA and TurB regulons (Fig. 5). In the case of CDSs in pCAR1, the independency ratios of the Pmr regulon during the L and ES phases (70.6% and 83.1%) were also higher than those of the TurA (26.5% and 10.8%) and TurB (49.0% and 14.7%) regulons (Fig. 5). This finding suggests that the role(s) of Pmr differs from those of the two chromosomally encoded MvaT proteins.

FIG 5.

Venn diagram of differentially transcribed CDSs in the KT2440 chromosome and the pCAR1 plasmid during the L and ES growth phases due to markerless deletion of pmr, turA, or turB. Blue and red numbers indicate upregulated and downregulated CDSs, respectively.

(iii) Effects of turA, turB, or pmr deletion on the transcription of pCAR1-carried genes.

Genes carried by pCAR1 can be divided into two groups: genes on the IncP-7 backbone, the conserved DNA region among IncP-7 plasmids, and accessory genes, such as carbazole and anthranilate degradation (car and ant) genes (19, 34). As shown in Fig. 5, the three MvaT proteins regulated different sets of pCAR1 genes. A large number of genes (47 genes) were upregulated by KT2440(pCAR1 Δpmr) during the ES phase (Fig. 5), suggesting that they were transcribed continuously in the stationary phase, similar to many genes on the chromosome (see Text S1 and Table S11 in the supplemental material). These genes included several on the IncP-7 backbone, as follows: repA and parW, involved in plasmid replication and partitioning (35, 36); ORF145a to ORF146, involved in the efficient transfer of pCAR1 (36); and ORF100 to ORF109, whose functions were not identified (Fig. 6; see Table S12). These findings suggest that Pmr regulates various genes on the IncP-7 backbone during the ES phase of growth.

FIG 6.

RNA maps of the entire pCAR1 plasmid obtained for P. putida KT2440(pCAR1) (KTPC), KT2440(pCAR1 Δpmr) (Δpmr), KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1) (ΔturA), and KT2440 ΔturB(pCAR1) (ΔturB). Black, blue, red, and green bars represent the signal intensities of the probes detected by tiling array assay. Black rectangles indicate the locations of annotated ORFs which are transcribed from left to right (above) and from right to left (below). The differentially transcribed regions are shown in gray boxes. The IncP-7 backbone region is indicated by the orange bidirectional arrow.

Transcriptional alteration in the regions of ORF100 to ORF109 and ORF145a to ORF146 was also found in KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1) and KT2440 ΔturB(pCAR1) (Fig. 6; see Table S12 in the supplemental material). The alteration patterns were opposite between the mutants during the L phase, i.e., the transcript levels were upregulated in KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1) and downregulated in KT2440 ΔturB(pCAR1). This suggests that TurA and TurB cooperate to regulate the transcription of genes in these two regions of pCAR1. Interestingly, the transcription levels of both of these regions were downregulated in KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1) during the ES phase. This result is in contrast to a previous report that TurA acts as a repressor of many genes during both the mid-L and ES phases in native KT2440 cells (12). It is therefore possible that genes on pCAR1 are regulated in a cooperative manner by MvaT proteins encoded on both the plasmid and the host cell chromosome.

Regarding pCAR1 accessory genes, transcript levels of the car gene cluster during the ES phase were commonly downregulated by turA or turB deletion (Fig. 6; see Table S12 in the supplemental material). Although some car genes were not downregulated during the L phase, their transcriptional values were lower than those for KT2440(pCAR1) (Fig. 6; see Table S12). Notably, the transcript levels of genes related to transposons (tnp) were also commonly downregulated by turA or turB deletion (Fig. 6; see Table S12). Therefore, TurA and TurB are important regulators not only of genes on the IncP-7 backbone but also of accessory genes of the plasmid.

Relationships between DNA-binding regions of MvaT proteins and their regulons in KT2440(pCAR1).

To analyze the relationships between DNA-binding regions of MvaT proteins and their regulons in KT2440(pCAR1), we applied putative operon information (DOOR2 [http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/DOOR/index.php]) and calculated the signal intensity (transcriptional value) of each operon from the chromosomal transcriptomic data on KT2440(pCAR1) and its derivatives used for the transcriptome comparison section (see Table S13 in the supplemental material). For the pCAR1 plasmid, we applied previously determined transcriptional units (31). We slightly modified the borders of some units and determined new units based on DOOR2 prediction so that all CDSs on pCAR1 were included in at least one unit and then calculated the signal intensity of each unit (see Table S14). While the classification of differentially transcribed operons (or units) (see Fig. S5) and the analysis of the regulon of each MvaT protein based on operons (see Fig. S6) yielded tendencies similar to those based on CDSs (Fig. 4 and 5) for both the chromosome and pCAR1, the total number of units in pCAR1 (88 units) was too small to discuss the ratio of the MvaT protein-binding operons; thus, we focused on the chromosomal operons.

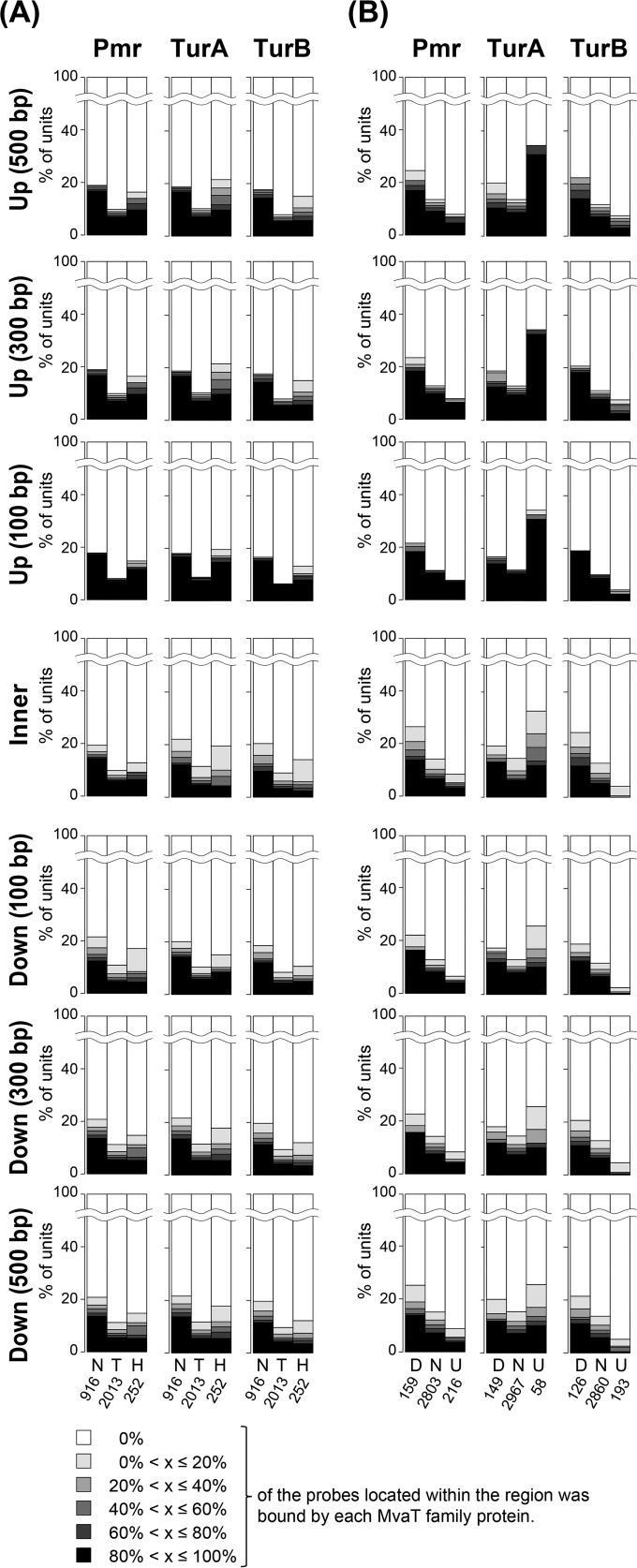

(i) All MvaT proteins bind to both nontranscribed and highly transcribed operons.

First, all 3,198 chromosomal operons were classified into the following three groups according to their signal intensities in wild-type KT2440(pCAR1) cells: (i) nontranscribed (signal intensity of <64), (ii) transcribed (64 ≤ signal intensity < 1,024), and (iii) highly transcribed (signal intensity of ≥1,024) operons. The operons in each group were then classified again according to the occurrences of the binding regions in their upstream, inner, and downstream regions (Fig. 7A). As a result, all three MvaT proteins bound to ∼20% of the flanking and inner regions of nontranscribed operons, compared with only ∼10% of the flanking and inner regions of transcribed operons (Fig. 7A). This could be explained by the fact that H-NS family proteins, including MvaT proteins, can act as silencers of xenogeneic regions, which frequently have a lower G+C content than that of the host genome (3). In fact, the average G+C content of 218 operons whose upstream (100, 300, and 500 bp), inner, or downstream (100, 300, and 500 bp) region was bound by at least one MvaT family protein was 57.4%, whereas that of all 916 nontranscribed operons was 61.2%.

FIG 7.

Relationships between the occurrences of MvaT protein-binding regions and the transcription levels of chromosomal operons. (A) All 3,198 operons on the P. putida KT2440 chromosome were classified into the following three groups according to their signal intensity in KT2440(pCAR1): (i) nontranscribed (N; signal intensity of <64), (ii) transcribed (T; signal intensity of 64 to 1,024), and (iii) highly transcribed (H; signal intensity of >1,024). The operons in each group were then classified again according to the coverage of MvaT protein-binding regions upstream (Up; 100, 300, or 500 bp upstream from the initial codon of the first CDS), within, or downstream (Down; 100, 300, or 500 bp downstream from the stop codon of the last CDS) of each operon. (B) All 3,198 operons were classified into the following three groups according to the fold change in each in KT2440(pCAR1 Δpmr), KT2440 ΔturA(pCAR1), and KT2440 ΔturB(pCAR1) compared with the level in KT2440(pCAR1): (i) downregulated (D; fold change of <0.5), (ii) not affected (N; fold change of 0.5 to 2), and (iii) upregulated (U; fold change of >2). The operons in each group were then classified again according to the occurrences of MvaT protein-binding regions upstream, within, and downstream of each operon. In both panels, the number of operons categorized into each group is shown beneath the corresponding abbreviation.

In terms of highly transcribed operons, the number of operons whose upstream, inner, or downstream region (100, 300, and 500 bp) was bound by at least one of the three MvaT proteins was larger than that for transcribed operons (Fig. 7A). Moreover, comparison of the results for upstream regions of different lengths suggested that their binding regions were shorter than those of the nontranscribed operons (Fig. 7A), because the ratio of MvaT protein (especially TurA)-bound operons decreased as the length of the upstream region increased. Moreover, the ratio of coverage by MvaT proteins was higher for upstream regions than for inner or downstream regions, suggesting that the three MvaT family proteins bound mainly to the region upstream of each operon.

(ii) Transcriptional regulation of TurA differs from that of Pmr and TurB.

Next, all 3,198 chromosomal operons were classified into the following three groups according to the fold change in each single-gene pmr, turA, or turB deletion mutant compared to KT2440(pCAR1): (i) downregulated (fold change of ≤0.5), (ii) not affected (0.5 < fold change < 2), and (iii) upregulated (fold change of ≥2). The operons in each group were then classified again according to the occurrence of binding regions in their upstream, inner, and downstream regions (Fig. 7B).

At first glance, the pattern of the bar plots for TurA appears to be different from those for Pmr and TurB. The ratio of operons bound by Pmr or TurB was higher for downregulated operons than for unaffected operons but was lower for upregulated operons; in contrast, the ratio of the operons bound by TurA was higher for both upregulated and downregulated operons. In addition, upregulated operons showed a higher TurA-binding ratio than that of downregulated operons. Note that none of the MvaT proteins bound >80% of differentially transcribed operons in each deletion mutant, suggesting that the changes in transcription of these operons were indirect effects mediated by other transcriptional regulators or that the DNA topology was altered by the binding of MvaT family proteins to remote regions. All three MvaT proteins covered upstream to downstream regions of the downregulated operons, while TurA bound particularly to the upstream regions of the upregulated operons. These results suggest that at least some MvaT proteins can act not only as transcriptional silencers (similar to xenogeneic silencers) but also as activators, possibly by affecting DNA topology in a multiply binding manner.

Conclusions.

In this study, we successfully clarified the binding regions present in both a plasmid and the host cell chromosome and the regulons of three MvaT proteins, one of which is encoded by pCAR1 and the other two of which are encoded by the chromosome of host P. putida KT2440 cells. Remarkably, the regulons of the MvaT proteins differed, although their binding regions were almost identical. It should be noted that the dissimilarity between the Pmr regulon and those of the other two proteins, TurA and TurB, was significant during the ES phase of growth. This finding suggested differences in their roles in host cells. A key role of Pmr as a “stealth” protein to minimize effects on host fitness has been described previously (18). The larger number of Pmr regulons during the ES phase indicated that the stealth function of Pmr is more effective during the ES phase than during the L phase.

This study also identified gaps in the commonality among the binding regions of the three MvaT proteins and a dissimilarity of their regulons. In previous reports, MvaT and MvaU, which are homologs of TurA and TurB, respectively, in P. aeruginosa PAO1, have been reported to bind to the same DNA regions on the PAO1 chromosome (7). No study to date has reported differences in their regulons; however, such differences are feasible. This contradiction may be explained by differences in (i) the amount of each protein in the cell, (ii) the preference for DNA-binding region sequences, (iii) the DNA-binding strength, or (iv) the affinity for other MvaT proteins in terms of forming hetero-oligomers. Therefore, posttranscriptional analyses will be necessary to understand the cooperative regulation of the host cell transcriptome by both plasmid-encoded and host chromosome-encoded MvaT proteins after conjugal transfer of plasmids. The other MvaT proteins, especially TurE, might also play an important role(s) in such cooperation. In addition, pCAR1 carries two other NAP genes, phu and pnd, which encode a histone-like protein and an NdpA-like protein, respectively (14, 15, 19). Further in-depth analyses of the relationships between H-NS family proteins and these other NAP genes are required to understand the transcriptional cross talk between plasmids and the host cell chromosome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences (PROBRAIN) and by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant 24380043. C.-S.Y. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships for foreign researchers from the JSPS.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03071-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dorman CJ. 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorman CJ. 2009. Nucleoid-associated proteins and bacterial physiology. Adv Appl Microbiol 67:47–64. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)01002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali SS, Xia B, Liu J, Navarre WW. 2012. Silencing of foreign DNA in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 15:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang FC, Rimsky S. 2008. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr Opin Microbiol 11:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tendeng C, Soutourina OA, Danchin A, Bertin PN. 2003. MvaT proteins in Pseudomonas spp.: a novel class of H-NS-like proteins. Microbiology 149:3047–3050. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.C0125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castang S, Dove SL. 2010. High-order oligomerization is required for the function of the H-NS family member MvaT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 78:916–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castang S, McManus HR, Turner KH, Dove SL. 2008. H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:18947–18952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808215105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki C, Yun CS, Umeda T, Terabayashi T, Watanabe K, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2011. Oligomerization and DNA-binding capacity of Pmr, a histone-like protein H1 (H-NS) family protein encoded on IncP-7 carbazole-degradative plasmid pCAR1. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 75:711–717. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki C, Kawazuma K, Horita S, Terada T, Tanokura M, Okada K, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2014. Oligomerization mechanisms of an H-NS family protein, Pmr, encoded on the plasmid pCAR1 provide a molecular basis for functions of H-NS family members. PLoS One 9:e105656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding P, McFarland KA, Jin S, Tong G, Duan B, Yang A, Hughes TR, Liu J, Dove SL, Navarre WW, Xia B. 2015. A novel AT-rich DNA recognition mechanism for bacterial xenogeneic silencer MvaT. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004967. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson KE, Weinel C, Paulsen IT, Dodson RJ, Hilbert H, Martins dos Santos VAP, Fouts DE, Gill SR, Pop M, Holmes M, Brinkac L, Beanan M, DeBoy RT, Daugherty S, Kolonay J, Madupu R, Nelson W, White O, Peterson J, Khouri H, Hance I, Lee PC, Holtzapple E, Scanlan D, Tran K, Moazzez A, Utterback T, Rizzo M, Lee K, Kosack D, Moestl D, Wedler H, Lauber J, Stjepandic D, Hoheisel J, Straetz M, Heim S, Kiewitz C, Eisen J, Timmis KN, Düsterhöft A, Tümmler B, Fraser CM. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 4:799–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renzi F, Rescalli E, Galli E, Bertoni G. 2010. Identification of genes regulated by the MvaT-like paralogues TurA and TurB of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 12:254–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rescalli E, Saini S, Bartocci C, Rychlewski L, de Lorenzo V, Bertoni G. 2004. Novel physiological modulation of the Pu promoter of TOL plasmid: negative regulatory role of the TurA protein of Pseudomonas putida in the response to suboptimal growth temperatures. J Biol Chem 279:7777–7784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda T, Yun C-S, Shintani M, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2011. Distribution of genes encoding nucleoid-associated protein homologs in plasmids. Int J Evol Biol 2011:685015. doi: 10.4061/2011/685015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shintani M, Suzuki-Minakuchi C, Nojiri H. 2015. Nucleoid-associated proteins encoded on plasmids: occurrence and mode of function. Plasmid 80:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorman CJ. 2014. H-NS-like nucleoid-associated proteins, mobile genetic elements and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. Plasmid 75:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle M, Fookes M, Ivens A, Mangan MW, Wain J, Dorman CJ. 2007. An H-NS-like stealth protein aids horizontal DNA transmission in bacteria. Science 315:251–252. doi: 10.1126/science.1137550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yun CS, Suzuki C, Naito K, Takeda T, Takahashi Y, Sai F, Terabayashi T, Miyakoshi M, Shintani M, Nishida H, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2010. Pmr, a histone-like protein H1 (H-NS) family protein encoded by the IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1, is a key global regulator that alters host function. J Bacteriol 192:4720–4731. doi: 10.1128/JB.00591-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nojiri H. 2012. Structural and molecular genetic analyses of the bacterial carbazole degradation system. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76:1–18. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyakoshi M, Shintani M, Terabayashi T, Kai S, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2007. Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 harboring the completely sequenced IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1. J Bacteriol 189:6849–6860. doi: 10.1128/JB.00684-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Russell D. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shintani M, Habe H, Tsuda M, Omori T, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2005. Recipient range of IncP-7 conjugative plasmid pCAR2 from Pseudomonas putida HS01 is broader than from other Pseudomonas strains. Biotechnol Lett 27:1847–1853. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-3892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jager W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Puhler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. 1990. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi KH, Schweizer HP. 2005. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol 5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shintani M, Takahashi Y, Tokumaru H, Kadota K, Hara H, Miyakoshi M, Naito K, Yamane H, Nishida H, Nojiri H. 2010. Response of the Pseudomonas host chromosomal transcriptome to carriage of the IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1. Environ Microbiol 12:1413–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyakoshi M, Nishida H, Shintani M, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2009. High-resolution mapping of plasmid transcriptomes in different host bacteria. BMC Genomics 10:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki-Minakuchi C, Hirotani R, Shintani M, Takeda T, Takahashi Y, Matsui K, Vasileva D, Yun C-S, Okada K, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2015. Effects of three different nucleoid-associated proteins encoded on IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1 on host Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2869–2880. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00023-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi Y, Shintani M, Takase N, Kazo Y, Kawamura F, Hara H, Nishida H, Okada K, Yamane H, Nojiri H. 2015. Modulation of primary cell function of host Pseudomonas bacteria by the conjugative plasmid pCAR1. Environ Microbiol 17:134–155. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perocchi F, Xu Z, Clauder-Münster S, Steinmetz LM. 2007. Antisense artifacts in transcriptome microarray experiments are resolved by actinomycin D. Nucleic Acids Res 35:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers KS, Yan H, Ong IM, Chung D, Liang K, Tran F, Keleş S, Landick R, Kiley PJ. 2013. Genome-scale analysis of Escherichia coli FNR reveals complex features of transcription factor binding. PLoS Genet 9:e1003565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shintani M, Nojiri H. 2013. Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) carrying catabolic genes, p 167–214. In Malik A, Grohmann E, Alves M (ed), Management of microbial resources in the environment. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shintani M, Yano H, Habe H, Omori T, Yamane H, Tsuda M, Nojiri H. 2006. Characterization of the replication, maintenance, and transfer features of the IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1, which carries genes involved in carbazole and dioxin degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:3206–3216. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3206-3216.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shintani M, Tokumaru H, Takahashi Y, Miyakoshi M, Yamane H, Nishida H, Nojiri H. 2011. Alterations of RNA maps of IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1 in various Pseudomonas bacteria. Plasmid 66:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.