Abstract

The quintessential property of developing cardiomyocytes is their ability to beat spontaneously. The mechanisms underlying spontaneous beating in developing cardiomyocytes are thought to resemble those of adult heart, but have not been directly tested. Contributions of sarcoplasmic and mitochondrial Ca2+-signaling vs. If-channel in initiating spontaneous beating were tested in human induced Pluripotent Stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPS-CM) and rat Neonatal cardiomyocytes (rN-CM). Whole-cell and perforated-patch voltage-clamping and 2-D confocal imaging showed: 1) Both cell types beat spontaneously (60-140/min, at 24°C); 2) Holding potentials between −70 to 0mV had no significant effects on spontaneous pacing, but suppressed action potential formation; 3) Spontaneous pacing at −50mV activated cytosolic Ca2+-transients, accompanied by in-phase inward current oscillations that were suppressed by Na+-Ca2+-exchanger (NCX)- and ryanodine receptor (RyR2)-blockers, but not by Ca2+- and If-channels blockers; 4) Spreading fluorescence images of cytosolic Ca2+-transients emanated repeatedly from preferred central cellular locations during spontaneous beating; 5) Mitochondrial un-coupler, FCCP at non-depolarizing concentrations (~50nM), reversibly suppressed spontaneous pacing; 6) Genetically encoded mitochondrial Ca2+-biosensor (mitycam-E31Q) detected regionally diverse, and FCCP-sensitive mitochondrial Ca2+-uptake and release signals activating during INCX oscillations; 7) If -channel was absent in rN-CM, but activated only negative to −80mV in hiPS-CM; nevertheless blockers of If-channel failed to alter spontaneous pacing.

Keywords: Pacing, electrophysiology, calcium, ion channels, mitochondria, sarcoplasmic reticulum, rat neonatal cardiomyocytes, cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells, genetically engineered fluorescent probes

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

In studies exploring the mechanisms of cardiac pacemaking much attention has been focused on processes that underlie the slow diastolic depolarization, that in SA-nodal cells start at −60 mV and terminates with upstroke of the action potential mediated by Ca2+ current. The primary candidates for slow diastolic depolarization have been the activation of: 1) inward If current (HCN2 and HCN4 genes [1-5]); 2) inward Na+-Ca2+ exchanger current (INCX) activated by release of Ca2+ from ryanodine receptor (RyR2) [6-8]; 3) turnoff of K+ current in Purkinje fibers [9-11] and activation of Na+-K+ ATPase or leak-type inward current [12, 13].

In considering the mechanisms of pacing, it is possible that one process may dominate in sino-atrial pacing while other mechanisms become critical in Purkinje fibers, [9-11] or in developing myocytes and pathological conditions. But, it is also plausible that the robust, persistent heartbeat requires interactions of number of entrained Ca2+- and membrane potential-dependent oscillators [14], which may be modulated by mechanical stimuli [15, 16], mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes, [17, 18], and oxidative stress [19].

We chose to examine spontaneous pacing in developing myocytes by quantifying their pacing frequency under control conditions and when action potential generation were prevented by voltage-clamping the cells at fixed holding potential of −50mV, allowing pacing to be monitored through cell shortening, INCX oscillations, and cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+-transients. After finding that generation of action potentials had little effect on pacing frequency, we proceeded to probe the role in Ca2+ signaling at −50mV to determine: 1) How robust were the Ca2+ oscillations in rN-CM and hiPS-CM; 2) How did they compare with SA-nodal Ca2+ oscillations, reported to rise at random sub sarcolemmal locations and be suppressed by clamping the membrane potential [14, 20], and 3) What were the contributions of mitochondria, where Ca2+ fluxes throughmitochondrial Ca2+-uniporter and the Na+-Ca2+-exchanger are suggested to buffer cytosolic Ca2+, thereby modulating pacing frequency [17, 18]. Others have suggested, however, that mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes are too small to have significant effects on cellular Ca2+ signaling physiologically [21].

To address these issues we used two models of developing myocytes, rN-CM and hiPS-CM. Compared to adult rodent cardiomyocytes, neonatal myocytes are reported to have altered functional protein expression (increased INCX and T-type Ca2+ current and decreased IK1, IKs, and IKr etc. [22], which might predispose them to spontaneous pacing. In general, hiPS-CMs have an immature structure (rounded or polygonal shape, few myofibrils and z-lines) and electrophysiologically express lower levels of IK1 and Ito. Most cell-line colonies appear to contain myocytes with ventricular, atrial and nodal action potential phenotypes. In addition, variability between different hiPS-CM cell-lines is even larger driving the ongoing effort to guide cellular differentiation [23]. We have previously reported on the hiPS-CMs used in the present study and found their Ca2+-signaling properties to be stable and dominated by ICa-triggered release of Ca2+ from the SR [24, 25, 26]. While both cell types continued to beat spontaneously under a broad range of experimental conditions, the critical role of subcellular Ca2+ signals was seen most clearly when they were dialyzed with Fluo-4, or infected with genetic probes targeted to RyR2 (GCamP6-FKBP [27]) or cytochrome-C (mitycam-E31Q [28]), and were voltage-clamped at −50mV to prevent the activation of any voltage-gated ion channels, but allowed activation of currents (INCX) generated by release of Ca2+.

To suppress motion-induced imaging artifacts or possible mechanical feedback mechanisms, we used firmly attached cultured myocytes and, in addition, incubated the cells with blebbistatin to desensitize the myofilaments to Ca2+ [29]. The voltage-clamped myocytes were also dialyzed with 5mM ATP to prevent exhausting them metabolically or when the mitochondrial un-coupler FCCP was used at concentrations (~50nM) that only stimulates mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, without depolarizing the mitochondria [30].

This is the first study to compare the details of Ca2+ signaling in two different spontaneously beating developing cell-types. The data suggests that spontaneous beating in hiPS-CM or rN-CM is triggered by rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations that activate in-phase NCX-currents, are independent of If expression, brief (~1min) suppression of ICa, or changes (~20s) in holding potential, and point to cross-talk between SR and mitochondria as a critical pacing mechanism. Imaging showed no indication that cellular Ca2+ transients start as random mutually reinforcing local sub-sarcolemmal Ca2+ releases. Rather, they rose from preferred central location and spread throughout the cell in a repeatable pattern. Mitycam-E31Q signals confirmed the presence of substantial mitochondrial Ca2+ transients, but also showed unexpected regional diversity between peripheral mitochondria that sequestered Ca2+ (Cf. [18, 30]), and peri-nuclear mitochondria that released Ca2+ accompanying the cytosolic Ca2+ transients.

2. Methods

2.1 General experimental approach

Experiments with spontaneously beating hiPS-CM [25, 26] and rN-CM [26, 31] cultures were carried out in accordance with national and institutional guidelines. The beating was examined at 24 and 35°C in intact cells and in single cells that were voltage- or current-clamped in configurations where the membrane under the patch pipette was either subjected to amphotericin B perforation or ruptured to allow cell dialysis. Holding potentials of −50 or −60mV were used to measure spontaneous oscillations in membrane current INCX, without activating other voltage-dependent channels, If and Ica. Ca2+ oscillations were recorded fluorometrically using dialyzing solutions with 0.1mM Fluo-4 or transient expression of either FKBP-linked GCamP6 [27] or a novel mitochondrially-targeted probe (mitycam-E31Q [28]).

2.2. Neonatal cardiomyocyte (rN-CM) isolation

Rat neonatal CMs (rN-CM) were isolated using an isolation kit from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ 08701). One to six day-old neonatal rats were decapitated and the beating hearts were surgically removed and placed in chilled Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). The main vessels and atria were removed and the ventricles were minced with a razor blade to pieces <1mm3 that were incubated in HBSS with trypsin (50μg/ml) for 14-16h at 4°C. The digestion was then arrested by exposure to trypsin inhibitor (200μg/ml) for 20min in 37°C. Thereafter collagenase (100U/ml) was used for 30min to isolate single rN-CM, which were filtered through a cell strainer and centrifuged at 1000rpm for 3min. Cells were re-suspended in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% non-essential amino acids, plated on 100mm dishes and placed in the incubator for 1-1.5h to eliminate fibroblasts. rN-CM overall viability was ~80%. Isolated single rN-CM were plated onto non-treated glass cover slips and used for electrophysiological experiments.

2.3. Cultivation of hiPS cells and preparation of hiPS-CM

Human iPS-CMs were produced by transfecting somatic cells from a healthy control individual with a set of pluripotency genes (OCT4, SOX2, cMYC, and KLF4) [32]. The generation, cardiac differentiation and characterization of these cells have been reported [24-26].

2.3.1. Culture of undifferentiated human induced pluripotent stem (hiPS) cells

The hiPS cells were maintained on mitomycin C-treated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) prepared in our laboratory in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with Glutamax, 20% knockout serum replacer, 1% nonessential amino acids (NAA), 0.1mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME, Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), 50ng/ml FGF-2 (PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany). Cells were passaged by manual dissection of hiPS cell colonies every 5-6 days.

2.2.2. Cardiac differentiation

Cardiac differentiation of hiPS cells was carried out on the murine visceral endoderm-like cell line END2, which was provided by C. Mummery (Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands) [33]. END2 cells were mitotically inactivated for 3 hours with 10μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany) and 1.2×106 cells were plated on 6cm dishes coated with 0.1% gelatin one day before initiation of hiPS cell differentiation. To initiate co-cultures, hiPS cell colonies were dissociated into clumps by using collagenase IV (Invitrogen, 1 mg/ml in DMEM/F-12 at 37°C for 5-10 minutes). The differentiation was carried out in knockout-DMEM containing 1mM L-glutamine, 1% NAA, 0.1mM βME and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100U/ml and 100μg/ml, respectively). The co-culture was left undisturbed at 37°C/5% CO2 for 5 days. Medium change was performed first on day 5 and later on days 9, 12 and 15 of differentiation.

2.3.3. Preparation of hiPS-CM for patch-clamp experiments

Beating areas were micro-dissected mechanically at day 40-45 of differentiation and dissociated with collagenase B. Single cardiomyocytes derived from hiPS cells (hiPS-CM) were then plated on fibronectin (2.5μg/ml) -coated 12 or 25mm glass cover slips and incubated for 36-72h before their use in electrophysiological experiments.

2.3.4. Cardiomyocytes derived from mouse iPS cells

(miPSC-CM) were prepared by methods described previously [34, 35] and were used in experiments probing the pacemaker current, If (Fig. 7). This iPS cell line (cloneAT25) was genetically modified to express EGFP and puromycin resistance genes under the control of α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) promoter to enable visualization and generation of pure CM. For the purpose of this study, murine iPS-CMs were not subjected to antibiotic selection and were analyzed between days 35-40 of differentiation.

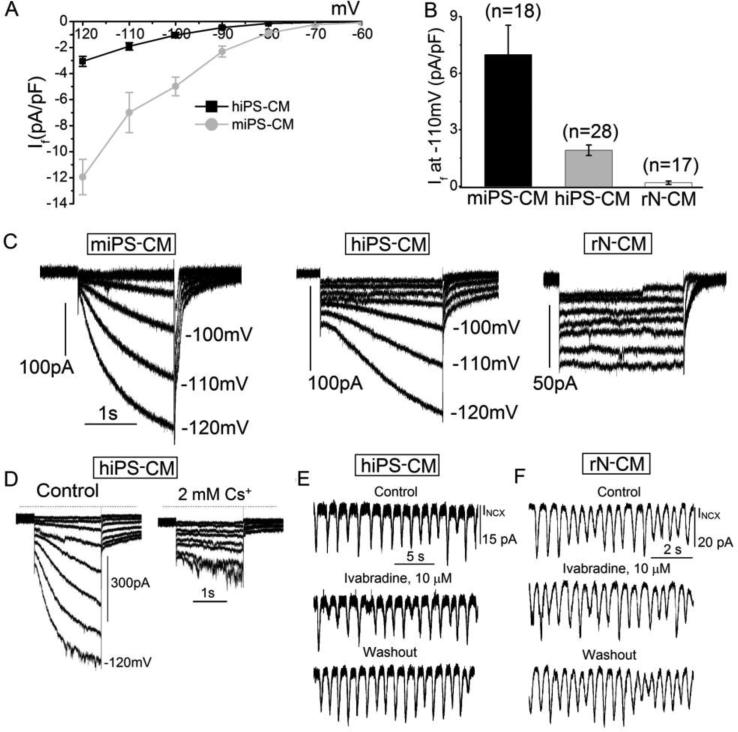

Figure 7.

If and its lack of effect on pacing at fixed membrane potential. A: Voltage-dependence of If in mouse (miPS-CM) and human (hiPS-CM) stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. B: Average If at −110mV is larger in mouse than in hiPS-CM, and is virtually absent in rN-CM. C: Sample traces of membrane current in the three cell types during 2.5s hyperpolarizations from −60mV to potentials from −70 to −130mV. D: Sample recordings with the same protocol in hPS-CM showing block of If by 2mM Cs+. E & F: Addition of 10 μM ivabradine to suppress If had no effect on oscillations of INCX in hiPS-CM (E) or rN-CM (F). The cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C and dialyzed with a solution containing 100μM EGTA.

2.4. Voltage-clamp procedures

Cells were voltage-clamped in the whole-cell configuration at −50 or −60mV tomeasure spontaneous oscillations in membrane current using a Dagan amplifier and pClamp software (Clampex 10.2). Action potentials were recorded in the current-clamp mode. Borosilicate patch pipettes were prepared using a horizontal pipette puller (Model P-87, Sutter Instruments, CA). The pipettes had a resistance of 3–5MΩ. In most experiments the membrane under the patch pipette was ruptured and the cells dialyzed with Ca2+-buffered pipette solutions containing (in mM): 110 Cs-aspartate, 15 NaCl, 20 TeaCl, 5 Mg-ATP, 0.1 EGTA with or without 0.05 or 0.1 Fluo-4, 0.1 CaCl2 ([Ca2+]i ≅ 100nM), 10 glucose and 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.2 with CsOH). In some experiments the cells were examined with the perforated patch technique using pipette solutions containing (in mM): 145 Cs-Glutamate, 9 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.2 with CsOH), and amphotericin B (Fisher Scientific) 0.69mg/ml. The extracellular solution used during experiments contained (in mM): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH). Rapid applications of 3mM caffeine and other compounds were used in the external K+-free solutions to probe the cellular Ca2+ stores or spontaneous Ca2+ releases from SR. While most experiments were carried out at room temperature, 24°C, some were performed at 35°C as indicated in the legends.

2.5. Fluorometric Ca2+ measurements in voltage-clamped cells

Cytosolic Ca2+, [Ca2+]i, was measured routinely by including 0.1mM Fluo-4 pentapotassium salt in the dialyzing pipette solution. Whole-cell fluorescence was measured using excitation with 460nm light from an LED-based illuminator (Prismatix, Modiin Ilite, Israel) and detection of emitted light (>500nm) with a photomultiplier tube that was placed behind a moveable, adjustable diaphragm, which served to limit the area of detection to the voltage-clamped cell. Fluo-4 loaded, voltage- or current-clamped cells were also imaged using rapid 2-D confocal microscopy (Odyssey XL, Noran Instruments, Middleton, WI) to chart the spread of spontaneous cytosolic Ca2+ transients (Figs. 4 & 5; [36]). The stacks of fluorescence images were collected at 30 or 120Hz, using a 63x objective (Zeiss Plan-achromat, NA 1.4, oil) providing sampling on a 0.13μm grid.

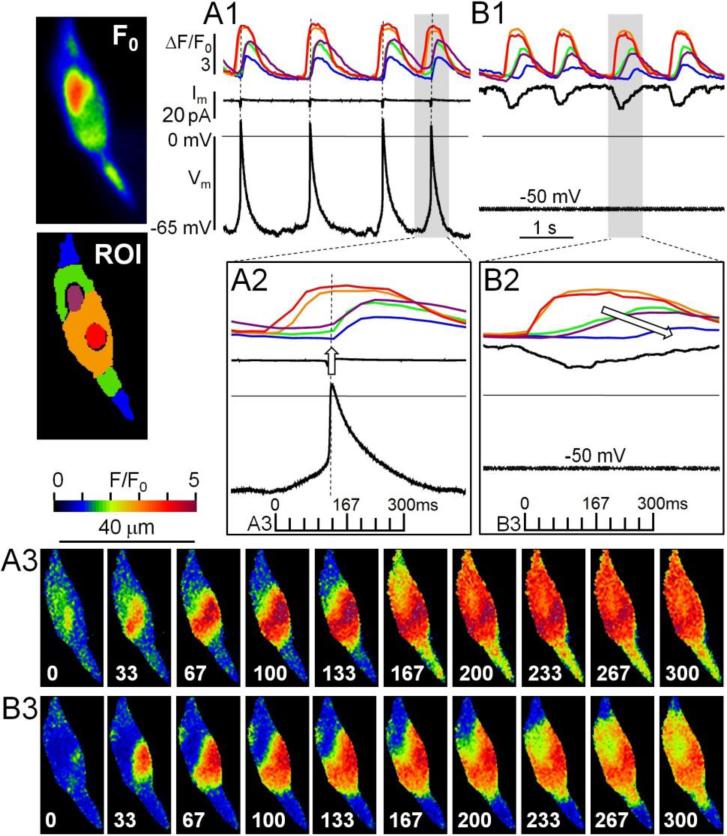

Figure 4.

The beating rates of a rN-CM are similar whether it generates action potentials under current-clamp control (A1, A2, A3) or Na+-Ca2+ exchanger current is recorded at −50mV holding potential (B1, B2, B3). A1, B1, A2, B2: Time course of color-coded regional Ca2+ signals (ΔF/F0), membrane current (Im), and membrane potential (Vm). A3 & B3: Two sequences of 10 ratiometric fluorescence images measured at the times indicated in panels A2 and B2. F0: Baseline fluorescence. ROI: Color-coded regions of interest (Red: approximate origin of spreading Ca2+ signals; purple: nucleus). Cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C, and dialyzed with a solution containing 50μM Fluo-4 to permit 2-D confocal imaging of cytosolic Ca2+ at 30 Hz.

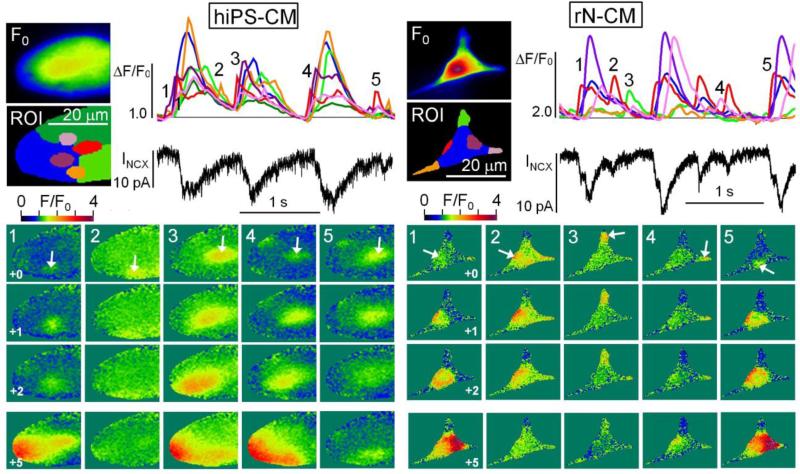

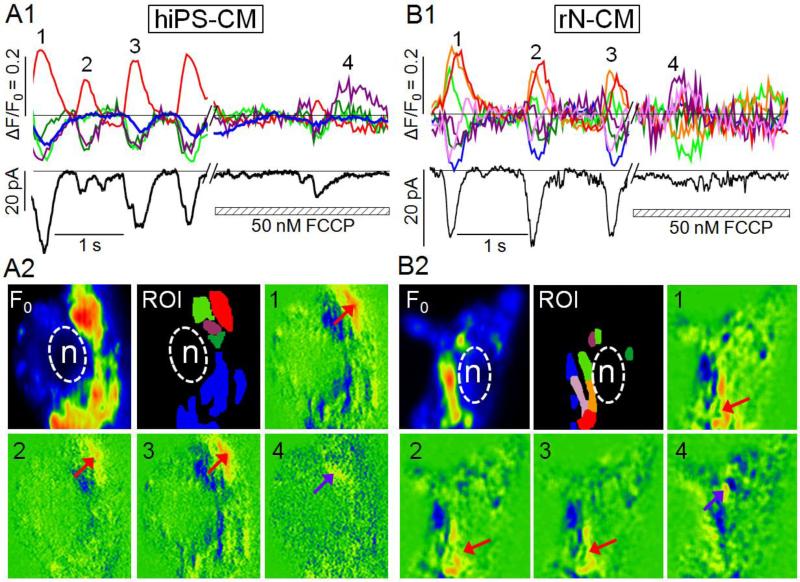

Figure 5.

Confocal images of spreading cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in hiPS-CM (Movie_S2) and rN-CM (Movie_S3). The larger images in each panel show the baseline fluorescence (F0) measured with dialyzed Fluo-4 and color-coded regions of interests (ROI) that were chosen to correspond to the shifting origins of Ca2+ waves and the larger expanses between them. The traces show the time course of the normalized fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0) in the ROIs and the simultaneously measured INCX. For each cell, the onset of each of 5 Ca2+ transients (1-5) is illustrated by 4 ratiometric images (+0, +1, +2, and +5) that were displayed at 30Hz. The last (+5) was delayed 100ms from the previous (+2) to show to what extend the Ca2+-waves spread throughout the cell. As shown on the color scale, elevation of [Ca2+]i is indicated by successive transitions from a greenish hue to yellow and red colors. Notice that some beats do not develop fully (rN-CM: 2, 3 and 4; hiPS-CM: 2 and 5) and that this is associated with reduced INCX and shifting sites of origination of the Ca2+ waves. Cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C at a holding potential of −50mV, dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1mM Fluo-4, and imaged confocally at 120Hz.

In other experiments we used adenoviral expression of genetically engineered Ca2+ probes. Cytosolic Ca2+ was measured in intact cells with a probe, GCamP6-FKBP that was targeted to ryanodine receptors with the FKBP-12.6 binding domain [27]. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signals were measured confocally with a novel mitycam probe, mitycam-E31Q [28] that is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix space by subunit VIII of human cytochrome c oxidase, contains mutant calmodulin with a relatively high Kd (~1.6μM) for binding of Ca2+, and uses yellow fluorescent protein as the reporting fluorophore. Unlike Fluo-4 and GCamP6-FKBP it responds to increasing Ca2+ concentrations with a decrease in fluorescence.

2.6. Image processing

The collected stacks of fluorescence images showing spontaneous cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations were low-pass filtered to display significant temporal and spatial variations. Individual frames were binned and filtered (2×2 or 3×3 pixel).

Cytosolic Ca2+ distributions measured with Fluo-4 were displayed ratiometrically (Figs. 4 & 5) as F/F0 meaning F(x,y,t)/<F0(x,y)> where F(x,y,t) is the low-pass filtered x-y image of a single frame measured at time t, and divisor is the baseline fluorescence image, F0 = <F0(x,y)> which was calculated from several frames collected between beats. This point-by-point division was carried out only out to the edge of the cell where the fluorescence intensity fell below 10-15 % of maximum. The ratiometric images were displayed at 30Hz on a rainbow scale where the baseline (F/F0 ≅ 1) was shown in blue and elevated [Ca2}+]i as warmer green, yellow, and red hues.

The mitochondrial Ca2+ distributions measured with mitycam-E31Q (Figs. 13 & 14) were displayed differentially as ΔF/F0 meaning (F(x,y,t)-<F0(x,y)>)/<F0> where <F0> is a single number calculated as the average of <F0(x,y)> over the entire cell. Generally short sequences of differential images (4-8) were pooled to clearly show local variation in mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling.

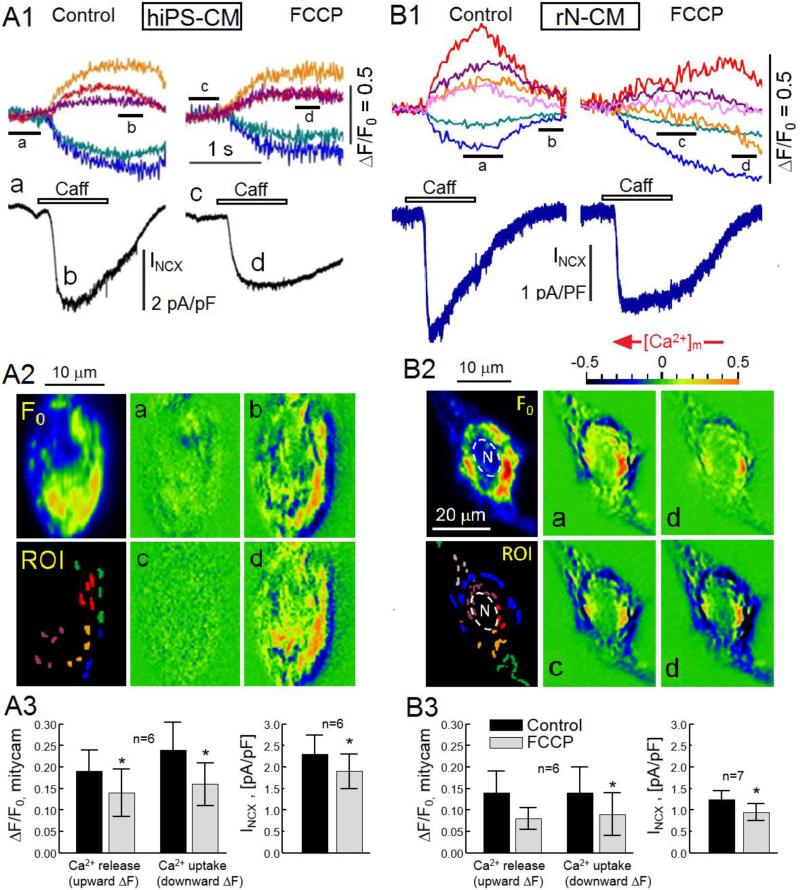

Figure 13.

Suppression of mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations by FCCP in myticam-E31Q infected hiPS-CM (A1, A2) and rN-CM (B1, B2). The tracings show changes in regional mitochondrial Ca2+ signals (top) and INCX (bottom) before and 30 s after exposure to 50nM FCCP (A1, B1). For each cell type the images (A2, B2) show baseline fluorescence (F0) and color-coded regions of interest (ROI, with “n” indicating nuclei) and 4 differential fluorescence images (measured at the times indicated along the traces) showing repeatable mitochondial Ca2+ signals before FCCP application (1, 2, 3) and smaller, more localized responses after (4). Increases in mitycam-E31Q fluorescence (reddish hues, arrows) correspond to reduced mitochondrial Ca2+, i.e. mitochondrial Ca2+ release. The cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C and dialyzed with a solution containing 100μM EGTA, while 2-D confocal imaging at 30 Hz was used simultaneously to measure mitochondrial Ca2+ reported by myticam-E31Q.

Figure 14.

Suppression of regional caffeine-induced regional mitochondrial Ca2+ signals by FCCP in a hiPS-CM (A1-3) and rN-CM (B1-3). A1 and B1: Time course of changes of fluorescence intensities in color-coded ROIs and INCX before (Control) and after addition of 50nM FCCP. A2 and B2: Baseline fluorescence (F0), ROIs (ROI), and changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ the times (a-d) indicated along the INCX trace. The cell was incubated in 10μM blebbistatin to suppress cell shortening. A3 & B3: Average values of INCX and of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and release measured in the most active regions of rN-CM and hiPS-CM. The cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C and dialyzed with a solution containing 100μM EGTA, while 2-D confocal imaging at 30 Hz was used simultaneously to measure mitochondrial Ca2+ reported by myticam-E31Q with a decrease in fluorescence.

The ratiometric images of cytosolic Ca2 distributions and the differential images of mitochondrial Ca2+ signals formed the foundations for the identification of color-coded regions of interest (ROI) with distinct kinetics. The image analysis was carried out using a custom designed program, Con2i [36].

2.6. Statistical analysis

Average values are presented in histograms and in the text as the mean ± the standard error of the mean for “n” cells. T-test was used to determine statistical significance. Significant findings are labeled with one (p< 0.05, *) or two stars (p < 0.01, **).

3. Results

3.1. Spontaneous beating: Membrane current and Ca2+ transients

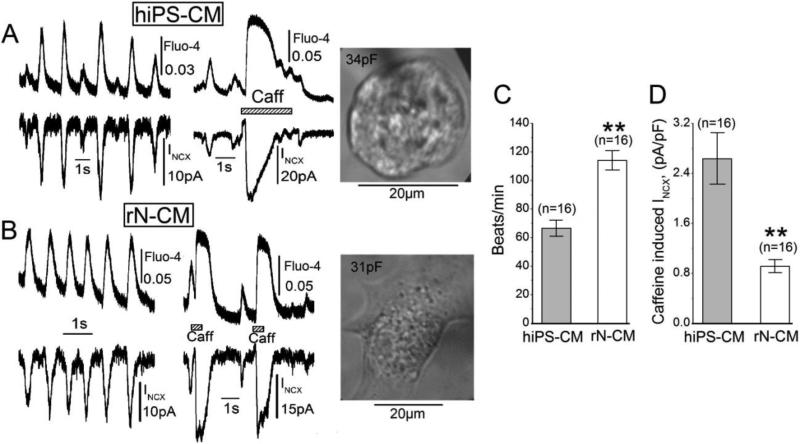

Figure 1 illustrates simultaneous measurements at room temperature, 24°C, of membrane current (Incx) and whole-cell cytosolic Ca2+ (Fluo-4) in hiPS-CM (A) and rNCM (B) that were voltage-clamped at −50 mV, dialyzed with an internal solution containing 100μM Fluo-4, and incubated with 10μM blebbistatin to suppress contractions [29]. Both cell types produced rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations that activated in-phase transient inward currents that were attributed to the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger since they occurred in the absence of membrane potential excursions and had nearly the same time course as the measured Ca2+ transients. Interruption of spontaneous rhythmic activity by rapid application of caffeine also generated transient rises in global Ca2+ that were accompanied by large transient inward INCX and transiently blocked pacing suggesting involvement of SR Ca2+ stores. Quantification of the beating frequency and the amplitude of caffeine-induced INCX in rN-CM and hiPS-CM, suggested somewhat higher beating rates in rN-CM (Fig. 1C), but larger density of INCX in hiPS-CM (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Simultaneous measurements of INCX current and Ca2+-signals in hiPS-CM (A) and rN-CM (B) voltage-clamped at −50 mV. A & B: Signals during spontaneous beating (left) and exposure to 3mM caffeine (middle) followed by microscopic bright field images of the voltage-clamped cell with labels indicating membrane capacitance (right). The bar graphs show differences in beating rate (C) and caffeine-induced INCX (D). Cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C, and dialyzed with a solution containing 100μM Fluo-4 to obtain whole-cell measurements of cytosolic Ca2+.

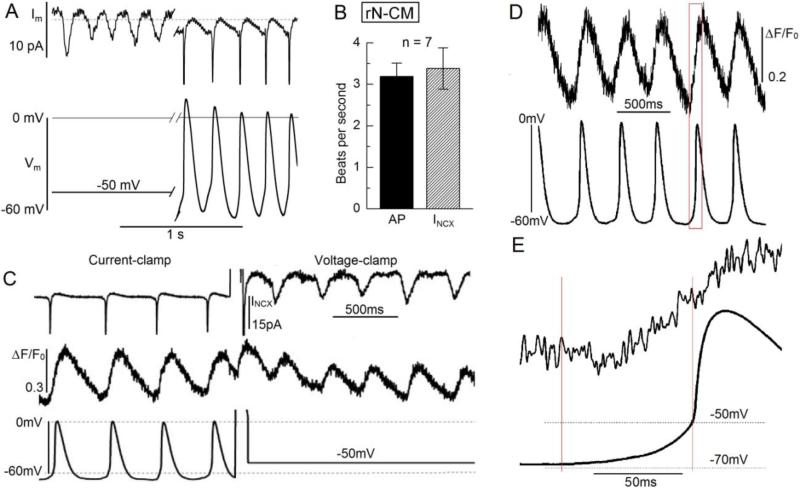

The spontaneous beating continued uninterrupted under broad array of experimental conditions. The visible contractions that guided the selections of cells had the same frequency as the Ca2+- and INCX -signals that generally continued for minutes after establishing the whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration. Recordings from rN-CM in the perforated-patch configuration and without Ca2+-dyes showed faster pacing when the temperature was raised to 35°C, but the frequency was the same whether the cells generated INCX transients at a holding potential of −50mV or generated action potentials in the current-clamp mode (Fig. 2 A & B). This was also the case when genetically engineered Ca2+ probes (Fig. 2 C) were used as indicators of beating, and it was observed under current-clamp conditions that the Ca2+-transients started to develop prior to the upstroke of the action potential (Fig. 2D &E). Similar action potentials were recorded in hiPS-CM in the current-clamp mode.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous beating in rN-CM measured at 35°C in the perforated patch configuration. A & C: Tracings of membrane current (Im) and membrane potential (Vm) measured while rapidly switching back and forth between current- and voltage-clamp modes in cells without (A) or with Ca2+ measurements (C-E, ΔF/Fo) using the biologically engineered Ca2+ probe GCamP6-FKBP. B: Comparison of average beating frequency of action potentials (AP) and INCX transients in 7 cells without expression of GCamP6-FKBP. Panel E shows a single beat from panel D on an expanded time scale illustrating that the onset of the Ca2+ signal coincides with the diastolic depolarization that precedes the upstroke of the action potential.

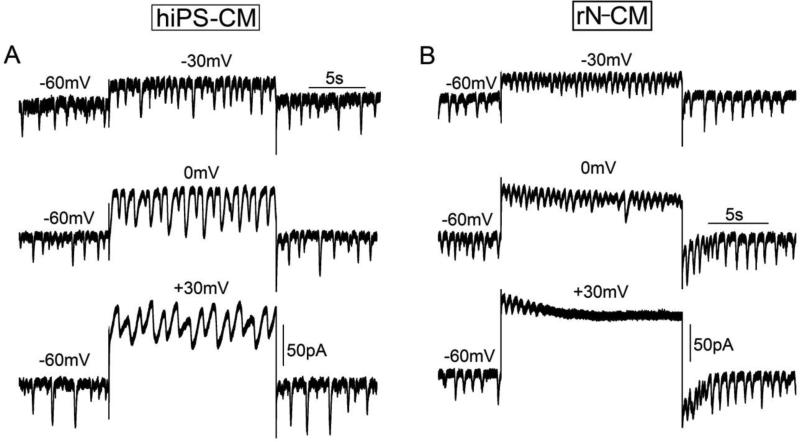

To examine the effects of membrane potential more fully we performed voltage-clamp experiments, with membrane rupture and cell dialysis, on hiPS-CM and rN-CM where the beating was assessed by measuring oscillations in the exchanger current, INCX, during clamp pulses lasting 15s. In both cell types the beating rate was insensitive to potentials ranging from −60 to 0mV, but often slowed or stopped at more positive voltages (Fig. 3). Spontaneous membrane current oscillations also continued to occur at hyperpolarizing potentials between −60 to −90mV, but the frequency of the oscillation decreased somewhat as their magnitudes became larger and longer (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Spontaneous beating of hiPS-CM (A) and rN-CM (B) are insensitive to changes in holding potential. Oscillations in INCX were insensitive to 15s voltage-clamp depolarizations from −60 to −30 and 0mV. Depolarization to +30mV stopped oscillations of INCX in rN-CMs, but not in hiPS-CM. Capacitance: rN-CM 35pF, hiPS-CM 36pF. Cells were voltage-clamped at 35°C and dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1mM EGTA.

To analyze these robust and persistent INCX and Ca2+ oscillations we performed 2-D confocal fluorescence microscopy at 30 or 120 Hz of voltage-clamped cell that were dialyzed with 50μM Fluo-4. Again we found that spontaneous Ca2+ transients (ΔF/F0) occurred with similar frequency whether the cell generated action potentials (Vm) with maximal diastolic potentials of ~-65mV (Fig. 4 A1), or generated inward INCX current at −50mV (Fig. 3 B1). Detailed examination, on an expanded time scale, revealed that the diastolic depolarization period coincided with local increases in Ca2+, which became endemic once the action potential was triggered (Fig. 4 A2, ↑).

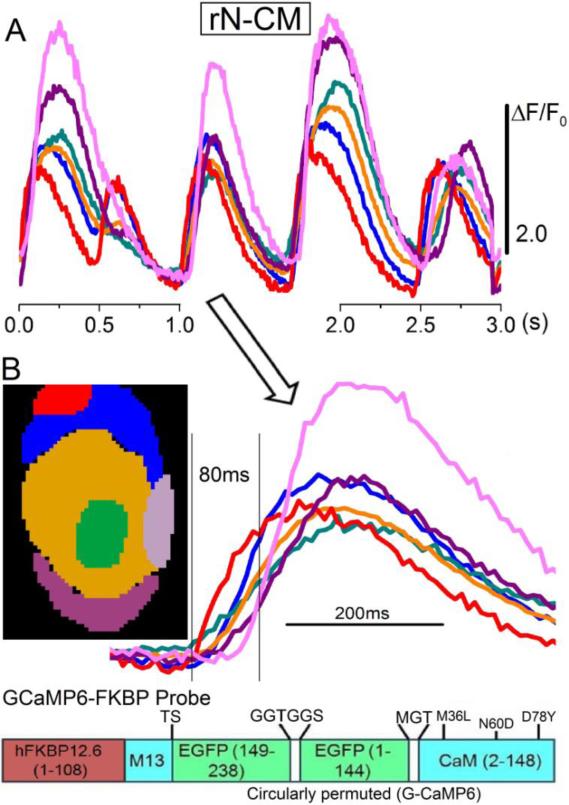

The spreading Ca2+ signals could be followed in sequential ratiometric confocal images (Fig. 4 A3 & B3) and the time-course of the normalized fluorescence intensities (corresponding to selected color-coded regions of interest, ROI; Fig. 4 A2 & B2). At 30Hz imaging speeds, both action potential- and voltage-clamp-activated image sequences show emergence of a local Ca2+ signal near the center of the cell (Frame 0, red ROI) and similar spreading of Ca2+ waves in the adjoining orange-colored ROI in the following 4 frames (33, 67, 100 and 133ms). Perhaps more significantly, under current-clamp conditions, large rises in cytosolic Ca2+ appear to take place (red ROI) during the slow diastolic depolarization period, prior to triggering of action potential and further rapid rise of Ca2+ that spreads to the ends of the cell (Fig. 3 A3, frame 167ms). Under voltage-clamp condition, however, the Ca2+ wave, in the same cell, continues to spread slowly and with decreasing amplitudes (Fig. 4 B2, 4 o'clock arrow) and appears not to invade the ends of the cell by 300ms (Fig. 4, B3, frame 300ms, blue ROI). Consistent with this pattern, most voltage-clamped, and dialyzed hiPS-CM and rN-CM generated Ca2+ waves that typically originated from a relatively fixed central, peri-nuclear location, spread to the entire cell and were accompanied by significant activation of INCX (10-30pA, but occasionally generated smaller Ca2+ signals that remained localized and generated little or no detectable INCX (Fig. 5). Using less invasive procedures, we used GCamP6-FKBP to measure Ca2+ signals in spontaneously beating, intact, non-dialyzed, non-patched cells and found persistent Ca2+ oscillations where synchronous rises in Ca2+ most likely reflect generation of action potentials, while the localized or slowly spreading Ca2+ signals resulted from failure to reach the thresholds for electrical excitation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Spontaneous Ca2+ signals at 35°C in an intact, non-voltage clamped rN-CM expressing GCamP6-FKBP probe. A: Spreading cytosolic Ca2+ signals recorded confocally at 120Hz. The curves show the time course of the fluorescence changes in selected ROIs. The same records are illustrated in Movie_S1. B: Color-coded regions of interest (left) and second beat on an expanded time scale (right). The diagram at the bottom shows the design of the expressed Ca2+-sensing probe GCamP6-FKBP.

Since pacing at distinct frequencies was robustly present in both rN-CM and hiPS-CM irrespective of methodology used (perforated-patch vs. cell dialysis vs. intact cells; dim light for whole-cell measurements vs. strong light for confocal imaging, 24 vs. 35°C, voltage- vs. current-clamp and Fluo-4 vs. GCamP6-FKBP as Ca2+ probe), in the next set of experiments we focused on Ca2+- and voltage-dependence of spontaneous pacing by: a) using holding potential of −50mV to prevent activation of voltage-gated ion channels; b) dialyzing with of 0.1mM Fluo-4 to allow detailed and fast Ca2+ measurements and c) experimenting at 24°C (instead of 35°C) to slow pacing frequency in order to more clearly monitor the sequence of events during the diastolic interval. With this general approach we assessed beating by measuring membrane current, INCX, and cytosolic Ca2+ transients where contractions were suppressed by blebbistatin [29].

3.2. Hyperpolarization-activated current, If, and spontaneous beating

Since spontaneous beating activity in the SA-nodal cells has been associated with the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated current, If, we examined the possible activation of this channel during spontaneous beating activity. We found significant expression of If channel in hiPS-CM, but not in spontaneously pacing rN-CM. Figure 7 A & B quantify the current density of If in hiPS-CM at different voltages and compares them to those recorded in mouse iPS-CM (miPS-CM) and rN-CM. It is clear that there was little or no significant activation of If at voltages positive to −80mV in either miPS-CM and hiPS-CM and none in rN-CM at any hyperpolarizing voltage. Furthermore, the small amounts of If activated at −80 or −90mV had activation kinetics that were too slow (seconds) to contribute significantly to rapid spontaneous beating (~2s−1). Figure 7 D, confirms that 2mM Cs+, reported to block If in SA-nodal cells [37], rapidly and reversibly blocked If, in hiPS-CM. Thus neither the voltage-dependence and kinetics, nor the pharmacology of If channels is consistent with its contribution to the spontaneous beating activity of rN-CM or mouse iPS-CM. Consistent with this idea, 10μM ivabradine, a potent and specific blocker of If in SA-nodal cells [38] had no effect on spontaneous beating frequency or on the current oscillations activated at −50mV in hiPS-CM or rN-CM (Fig. 7E & F).

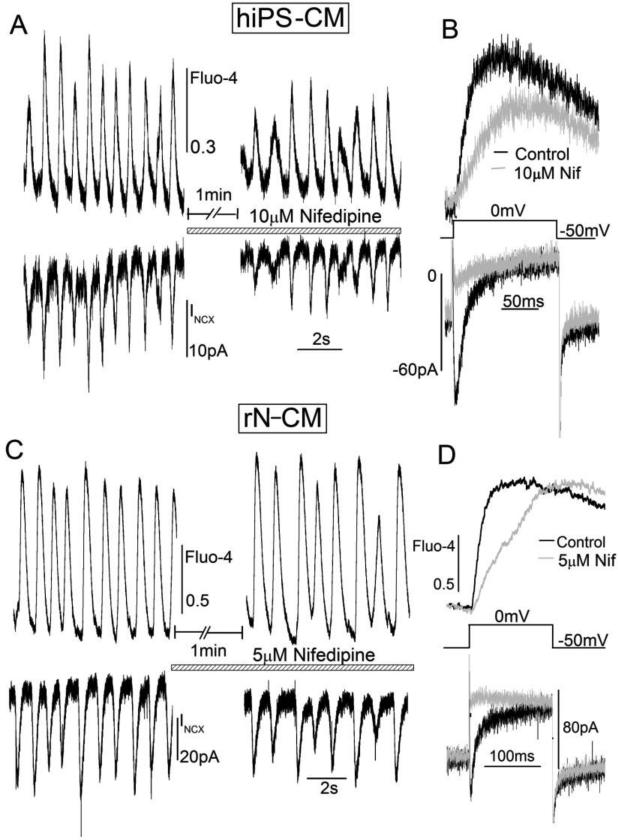

3.3. Ca2+ current and spontaneous beating

Since L-type Ca2+ channels are critically important in regulation of pacemaking activity in SA-nodal cells [37, 39], and in the light of recent reports that nifedipine suppresses spontaneous beating in hiPS-CM [40, 41], we measured the effectiveness of nifedipine in suppressing the spontaneous Ca2+ transient and membrane current oscillations recorded at −50mV. We found that 5-10μM nifedipine while fully suppressing ICa decreased the rate of spontaneous oscillation and their amplitude by only ~20% in hiPS-CM or rN-CM (Fig. 8 A & C) after ~1min. Under these conditions, significant rise in cytosolic Ca2+, though with slower kinetics, was activated with depolarizing pulses to 0mV in the ICa-suppressed cells (Fig. 8 B & D; upper traces), suggesting significant influx of Ca2+ on NCX and/or its release from the SR, independent of ICa-triggered release, underlies the spontaneous beating of these developing cardiomyocytes. Longer exposures (> ~5min) of nifedipine were accompanied by irreversible loss of ICa and irregular beating suggesting run-down or slow changes in the Ca2+ balance of the voltage clamped cells.

Figure 8.

The Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine blocks ICa (B, D), but has only a minor effect on spontaneous oscillations of INCX and [Ca2+]i (A, C) in hiPS-CM (A, B; 10μM, n=3) or rN-CM (C, D; 5μM, n=1). Panel B and D show that 5 or 10μM nifedipine effectively blocked ICa activated by depolarization to 0mV (lower traces) and delayed the development of Ca2+-dependent fluorescence (upper traces). Cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C using a holding potential of −50mV and dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1mM Fluo-4, which was excited with low intensity 460nm light for cytosolic whole-cell Ca2+ measurements.

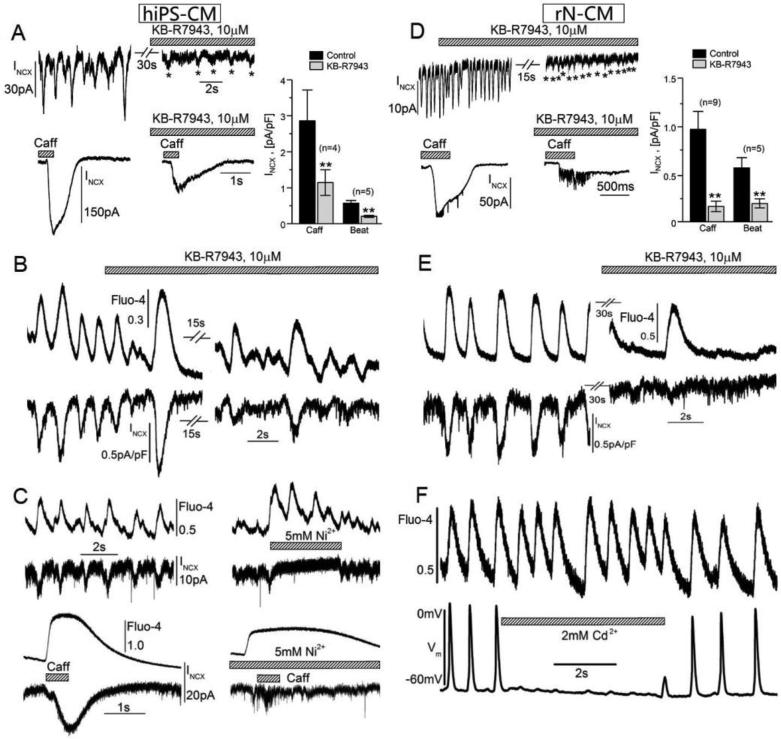

3.4. Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and spontaneous beating

To identify the molecular entity responsible for generation of spontaneous rhythmic oscillations in the membrane current in these minimally Ca2+-buffered (0.1mM EGTA or Fluo-4 plus 0.1mM Ca2+) cells, we tested the sensitivity of this current to NCX-blockers KB-R7943 (10μM), Ni2+ (5mM) and Cd2+ (2mM). KB-R7943 had little immediate effect (Fig. 9 A & D), but in 15-30s it decreased by 60-80% (histograms) the magnitude of spontaneously occurring transient inward currents and the currents activated by caffeine-triggered Ca2+-release in both hiPS-CM and rN-CM (Fig. 5 A & D). In voltage-clamped cells dialyzed with Fluo-4, we found that the greatly attenuated spontaneous oscillations of INCX that still persisted in the presence of KB-R7943 (*s in Fig. 9 A & D) were accompanied by cytosolic Ca2+ transients that were often somewhat irregular in frequency, but of near normal amplitude (Fig. 9 B & E). To achieve a faster and more complete and reversible block of INCX, we used Ni2+ (5mM) or Cd2+ (2mM). Under voltage-clamp conditions, Ni2+ effectively blocked INCX, but left strong spontaneous and caffeine-induced Ca2+ signals that, as expected, showed marked suppression of rate of relaxation (Fig. 9 C; Cf. [42]). Similarly, spontaneously developing Ca2+ signals continued unabated when rapid application of Cd2+ blocked the generation of action potentials in cells that were current-clamped at 35°C in the perforated patch configuration (Fig. 9 E). It is plausible that longer lasting exposures to KB-R7943 may block both sarcolemmal and mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchangers while divalent cations under current-clamp conditions may block the action potentials by blocking voltage-gated ion channels. Collectively the results illustrated in Fig. 9 suggest that rapid block of INCX does not abolish spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in hiPS-CM and rN-CM.

Figure 9.

KB-R7943 (A, B, D, E, 10μM), Ni2+ (C, 5mM), and Cd2+ (F) suppress INCX in hiPS-CM (A-C) and rN-CM (D-F), but do not abolish spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation or caffeine-induced Ca2+ release. A & D: Exposures to KB-R7943 for 15-30s suppress spontaneously oscillating (upper panels) and caffeine-induced INCX (lower panels) only by 60-80% (histograms) thereby leaving indications of continued Ca2+ oscillations (*). B & E: Simultaneous measurements with Fluo-4 confirm the continuation of spontaneous cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations when INCX is suppressed by KB-R7943. C: Rapid exposure of hiPS-CM to 5mM Ni2+ blocks INCX while accentuating associated spontaneous [Ca2+]i oscillations (top) and prolonging the duration of caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i transients (bottom). F: Rapid exposure of a current-clamped rN-CM reversibly blocked action potentials without affecting cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations measured with GCamp6-FKBP (Cf. Fig. 6). The cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C (A-E) using dialyzing solutions containing 100μM EGTA (A, D) or Fluo-4 (B, C, E) or current-clamped in the perforated patch configuration at 35°C (F).

3.5. ICa-gated Ca2+ release from the SR and spontaneous beating

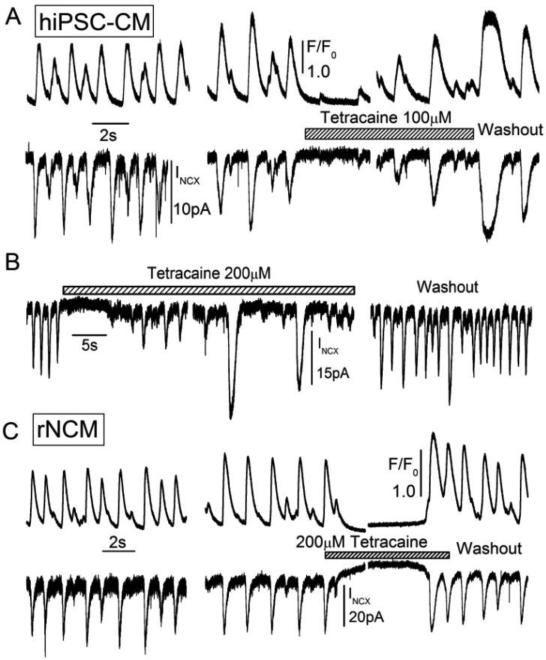

To probe the role of SR in the generation of spontaneous beating, we used agents that either blocked RyRs or depleted the SR Ca2+ content. We found that application of 100-200μM tetracaine, known to suppress SR Ca2+ release [43], arrested spontaneous beating rapidly and reversibly in both cell types clamped at −50mV (Fig. 10 A & C). Using longer exposures to tetracaine, spontaneous beating often recovered and was accompanied by sporadic larger releases of Ca2+ (Fig. 10 B). The first beat after washout of tetracaine was often accompanied by larger Ca2+ release and INCX, reflecting increased SR Ca2+ content during tetracaine block of RyRs.

Figure 10.

Transient suppression of spontaneous oscillations of Ca2+-dependent fluorescence (F/F0) and INCX in voltage-clamped hiPS-CM (A, B) and rN-CM (C) by the ryanodine receptor-blocker tetracaine (100 or 200 μM) during short-term (A, C) and long-term (B) exposure. The first beat after washout of tetracaine was generally larger, indicative of an increased SR Ca2+ load during tetracaine exposure. In some cells, during the tetracaine exposure and cessation of spontaneous activity, sporadic but large transient inward currents were activated (B), that were thought to be related to unblocking of tetracaine-block as the Ca2+ load of SR increases in the presence of the drug (A). Similar data were also obtained in rN-CM. Cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C at a holding potential of −50mV, and dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1mM Fluo-4, which was excited with low intensity 460nm light for whole-cell measurements of cytosolic Ca2+.

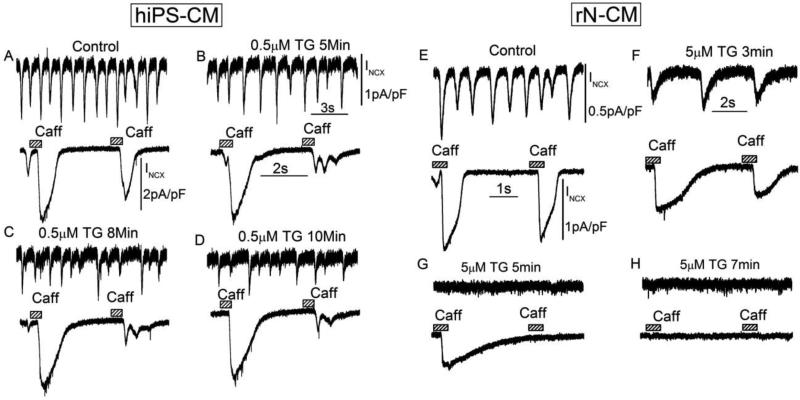

Thapsigargin, a widely used inhibitor of Ca2+-ATPase in mammalian cells, suppressed the spontaneously activating INCX in 3-5min and caffeine triggered INCX in 5-7min in rN-CM, when used in a concentration of 5μM (Fig. 11 E-H). The effects developed more slowly with 0.5μM thapsigargin in hiPS-CMs (Fig. 11 A-D). Thus both sets of data support the idea that Ca2+ release from the SR plays a critical role in supporting spontaneous beating in the developing cells.

Figure 11.

Effect of thapsigargin, an inhibitor of Ca2+-ATPases (SERCA2a) on membrane current, INCX, in hiPS-CM (A-D) and rN-CM (E-H). Each panel shows INCX during spontaneous oscillations at the top and responses to paired caffeine exposures (3mM) at the bottom. The four panels illustrating each cell type show results under control conditions (A, E) and the gradual effects of exposure of hiPS-CM to 0.5μM thapsigargin for 5min (B), 8min (C) and 10min (D) or rN-CM to 5μM thapsigargin for 3min (F), 5min (G) and 7min (H). Cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C at a holding potential of −50mV, and dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1mM EGTA.

3.6. Mitochondrial un-coupler FCCP arrests spontaneous pacing

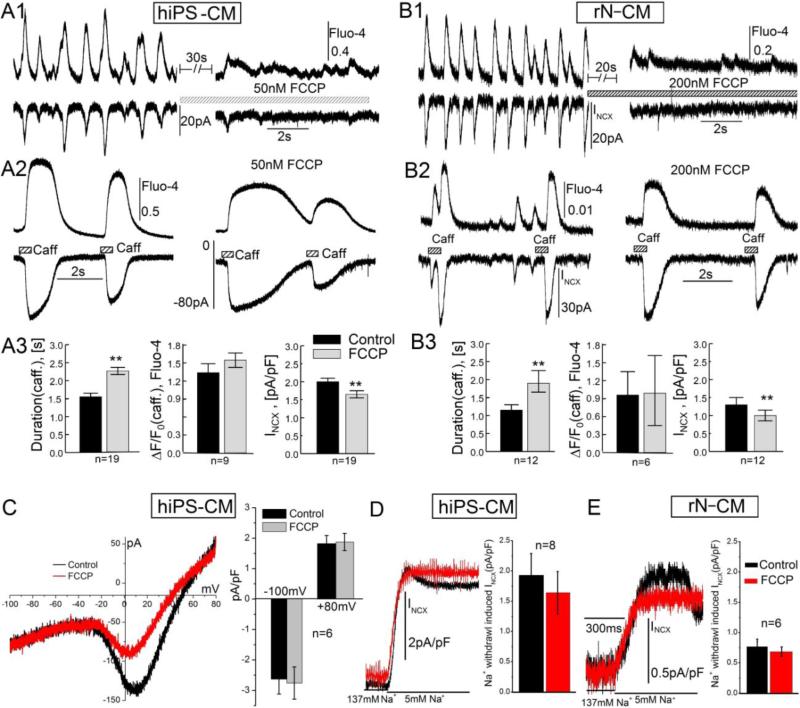

Since mitochondria constitute ~30% of the myocyte volume [44] and a number of reports suggest a critical role for mitochondria in cardiac Ca2+ signaling [18, 45], we probed the extent to which mitochondria regulate spontaneous beating. Using short exposures to low concentrations of FCCP (50-100nM), we found that this mitochondrial uncoupler abolished INCX and Ca2+ transients associated with spontaneous pacing (Fig. 12 A1 & B1). The suppressive effect of FCCP was accompanied by significant slowing in the rates of relaxation of the caffeine-induced INCX and Ca2+ transients (Fig. 12 A2 & B2), but amplitudes remained nearly intact (Fig. 12 A3 & B3), suggesting that SR Ca2+ loads and NCX activities were not affected substantially by FCCP in the low concentrations of drug used. These low concentrations of FCCP are reported to enhance oxidative mitochondrial metabolism without depolarizing the mitochondria [30] and were fully reversible after 2-3 minutes of drug washout.

Figure 12.

Suppression of spontaneous beating by the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP. A1-3 (hiPS-CM, 50nM FCCP) & B1-3 (rN-CM, 200nM FCCP): Matched tracings of Ca2+-signals (Fluo-4) and membrane current (INCX) showing strong suppression of spontaneous Ca2+ and INCX oscillations (A1, B1), but prolongation of the caffeine-induced (3mM) signals (A2, B2) with only minor changes in their amplitudes (A3, B3). C: Ramp-clamp data suggesting that 100nM FCCP slightly attenuated ICa (in the range −30 to 40mV) without affecting INcx. The histograms show that 100nM FCCP had no significant effects on the current measured at −100 and +80mV. D & E: INCX measured in response to Na+-withdrawal (137 → 5mM; TEA substitution) before (black) and after (red) treatment with FCCP in hiPS-CM (D) and rN-CM (E). The cells were voltage-clamped at 24°C and dialyzed with a solution containing 100μM Fluo-4 (A, B) or EGTA (C-E).

We also tested directly whether INCX might be suppressed by FCCP by using depolarizing/repolarizing ramp pulse protocols, from −50 to +80mV and back to −100mV, to measure both the influx and efflux of Ca2+ on NCX. Fig. 12 C shows that 100nM FCCP had no significant effect on INCX measured at −100 and +80mV even though it suppressed ICa as seen during the ramp-clamps at potentials between −30 and +60mV. This finding was further supported by the results where influx of Ca2+ on NCX was measured using the Na+ withdrawal procedure. Figure 12 D & E shows that the outward INCX activated on rapid withdrawal of Na+ (red and black traces) were not significantly affected by exposure to 50nM FCCP in either hiPS-CM or rN-CM (histograms), consistent with Fig. 6 C. The prolongation of relaxation time of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients, and suppression of spontaneous pacing by short exposures of FCCP (Fig. 12 A & B), suggests a direct role for mitochondria in the cycling of cytosolic Ca2+ and regulation of pacing.

3.7. Measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+ in mitycam-E31Q infected cells

In spontaneously beating hiPS-CM or rN-CM, infected for 2-3 days with a genetically encoded mitochondrial Ca2+-sensing probe, mitycam-E31Q [28], we measured oscillations in the global mitycam signals that accompanied membrane current oscillations. Such global signals were, however, small in amplitude, and varied in kinetics as also reported earlier for adult myocytes [46]. To examine whether regional heterogeneity in mitochondrial populations contributes to the variability of global mitycam signals, we used confocal microscopy to identify regions of interest (ROI) with different Ca2+-signaling profiles and analyzed the results along the same lines used for imaging of cytosolic Ca2+ with Fluo-4. Figure 13 illustrates how this approach was used to analyze the patterns of mitochondrial Ca2+ signals in hiPS-CM and rN-CM in control conditions and where spontaneous beating was suppressed by 30s exposures to 50nM FCCP. The images of baseline fluorescence (F0) showed that the mitycam-E31Q probe, targeted to mitochondrial subunit VIII of human cytochrome C, clustered around the nuclei of the cells (n). Under control conditions, as spontaneous beating activated large INCX transients (Figs.1-5, 7-13), the mitochondrial probe signal unexpectedly showed regionally diverse patterns, such that while some mitochondrial populations showed decrease in fluorescence (uptake of Ca2+), others displayed an increase in fluorescence corresponding to Ca2+ release. The mitochondrial populations showing Ca2+ release signals were essentially conserved in hiPS-CM (Fig. 13 A1 & A2, red trace and ROI) and rN-CM (Fig. 13 B1 & B2, red and orange traces and ROIs) from one beat to the next, consistent with findings of dominant pacing sites, (Figs. 4-6). The release sites were generally surrounded by mitochondria that appeared to concurrently take up Ca2+ (Fig. 13, green, blue, purple ROI in hiPS-CM; primarily blue ROI in rN-CM). Addition of FCCP suppressed the dominant pacing site and regular spontaneous beating, but left greatly reduced and discordantly activating INCX that were associated with more locally confined oscillatory mitochondrial Ca2+ signals where Ca2+ releases and uptakes were seen to switch back and forth between neighboring ROIs. For instance, as seen in the illustrated hiPS-CM (Fig. 13 A1), the release was seen to switch from the purple ROI to the red and back again. These patterns of mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling are characteristic of 4 recordings in rN-CM and 3 recordings in hiPS-CM and are consistent with the Fluo-4 measurements of cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 12 A & B) suggesting that mitochondria play an active role in Ca2+-mediated pacing in these developing cells.

Releases and uptakes of Ca2+ by distinct mitochondrial populations were also observed in both hiPS-CM and rN-CM in response to rapid puffs of 3mM caffeine that also activated large INCX (Fig. 14). As anticipated from Fig. 12, short (30-60s) exposures to 50nM FCCP significantly slowed the decay of INCX, (Fig. 14 A1 & B1, lower traces), but produced only minor reduction in its magnitude (Fig. 14 A3 & B3, right histograms). Simultaneously measured mitochondrial Ca2+ signals were similarly prolonged (Fig. 14 A1 & B1, upper traces) while their amplitudes corresponding to both uptake and release were reduced relatively little initially (Fig. 14 A3 & B3, left histograms). Similarly, baseline mitycam fluorescence after addition of FCCP was 80±3% (rN-CM, n=6) or 83±7% (hiPS-CM, n=6) percent of control, indicating that the mitochondrial Ca2+ content remained largely intact. The effects of exposure to 50-100nM FCCP for 1-3 min were fully reversible. When used in higher concentrations (1μM), FCCP irreversibly damaged mitochondrial Ca2+ handling.

4.1. Discussion

The quintessential property of developing cardiomyocytes is their ability to beat rhythmically in culture, a property also observed in early stages of embryonic development, long before the heart evolves its multi-chambered structure. Here, we have attempted to probe the mechanisms underlying the spontaneous rhythmic beating of cardiomyocytes in two cell models: 1) Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes isolated from 2-3 day old rat hearts, and 2) spontaneously beating human iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes [25]. Because we have already reported that Ca2+-signaling properties of rN-CM and hiPS-CM were similar to those of freshly isolated adult cardiomyocytes, [26, 31], our approach was to image focal changes in Ca2+ profiles in spontaneously beating cells either dialyzed with Fluo-4 or infected with genetically encoded Ca2+ probes directed at ryanodine receptors (GCamP6-FKBP) or mitochondria (mitycam-E31Q [28]). Fluo-4 confocal imaging showed that while Ca2+ signaling started at a preferred central location and spread throughout the cell in a repeatable pattern, the mitycam E31Q mitochondrial probe showed divergent patterns of Ca2+ release and uptake during spontaneous pacing. The finding that spontaneous pacing rate in developing myocytes were not significantly affected by triggering of action potential, but was highly sensitive to low concentrations of mitochondrial un-coupler FCCP, suggests that the primary pacing mechanism may be independent of activation of ion channels, but highly dependent on metabolic state of mitochondria.

4.2. Expression of hyperpolarization-activated current, If, and spontaneous rhythmic beating

Fig. 7 suggests significant differences in the level of expression of If in rN-CM and human or mouse iPS-CM. Interestingly, even though rat neonates do not express If (Fig. 7 A-C), the frequency of its spontaneous beating was significantly higher than that of human iPS-CM (Fig. 1). Expression of If in iPS-CM was more robust and was present in every cell examined, but If activated only at potentials negative to −80 mV in human and −70 mV in mouse iPS-CM, and was rapidly and reversibly blocked by 2mM Cs+ (Fig. 7 D) without significantly altering the pacing frequency, as reported also for human and rabbit SA-nodal cells [47, 48]. Thus, if If were to contribute to generation of spontaneous activity, it would have to carry significant inward current at voltages positive to −70 mV, clearly not the case here, where If is either absent or its kinetics too slow and activation-voltage too negative. Furthermore, the pacing rate was unaltered by blockers of If, (Fig. 7 E & F), changes in holding potential (Fig. 3, −60 to 0 mV), and the triggering of action potentials (Figs. 2, 4, 6). Pacing frequency did not vary significantly between intact nondialyzed cells (Fig. 6), and cells voltage-clamped at −50mV, but the frequency accelerated significantly (to ~3/s in rN-CM) when the temperature was increased from 24 to 35°C under perforated patch conditions (Fig. 2). Thus, our findings argue for a mechanism independent of membrane ion channels initiating the spontaneous rhythmic beating.

This raises the question as to the role of If current in mouse and human iPS-CM, as it is present in these cells (Fig. 7), and in mammalian SA-node, where it is proposed to initiate diastolic depolarization alone [3] or together with Ca2+-activated INCX [7]. It is a somewhat of over-looked observation that in SA-nodal cells too, there is a discrepancy between diastolic depolarization potentials (−60 to −40 mV) and activation range of If (negative to −70 mV), including human SA-node [48]. A combination of rapid 2-D Ca2+ imaging and voltage- and current-clamp studies might clarify the role of If in SA-nodal cells by examining whether sub-sarcolemmal Ca2+ transients always precede the diastolic depolarization. We suggest that If is critical in protecting the small pacemaker cells from the large voltage sink of bigger atrial cells by serving as a “functional insulator”. It is likely that without expression of HCN proteins, activating strongly and rapidly at potentials near the atrial resting potentials (~−90 mV), the SA-nodal cells would be hyperpolarized to more negative resting potentials of atrium, thereby preventing them from generating the diastolic depolarization necessary for pacing the heart. This property of If along with significantly lower expression of IK1 channels especially in SA-nodal/atrial junctional cells may serve as a dynamic “push-me pull-you” current oscillations that might amplify the oscillations set by the Ca2+ signaling mechanisms in central SA-nodal cells.

4.3. Rhythmic spontaneous Ca2+ release and NCX current oscillations

The central observation of this report is that spontaneous rhythmic oscillations of cytosolic Ca2+ and the accompanying INCX were consistently recorded in myocytes that were voltage-clamped at constant holding potentials of −50mV, where no ionic channels were allowed to activate (Figs. 1-5, 7-14). The sensitivity of these signals to KB-R7943, Ni2+ and Cd2+ suggest that the current oscillations (INCX) were triggered by cytosolic Ca2+ changes activating the NCX current (Fig. 9). Although the rhythmic activity was fairly constant, either at the onset of dialysis and before imaging laser light, they became more irregular following exposure to intense light of confocal imaging. Such irregularities were less apparent when imaging measurements were not attempted. Confocal examination of such rhythmic beating activity in cells dialyzed with Fluo-4 and held at −60 or −50 mV suggests multiple Ca2+ release sites. The stronger Ca2+ triggering sites appeared to invade the cell rapidly and fully (Figs. 4-6) while weaker sites were not able to invade the cell fully (Figs. 5 & 6). It is not clear as yet why the strong triggering sites give way to the weaker site, but since the frequency of spontaneously occurring rhythmic activity is not significantly altered by nifedipine (Fig. 8) or by holding potentials (−60 to 0 mV; Fig. 3), the data is consistent with activation of different Ca2+ pools capable of maintaining the rhythmic activity.

The Ca2+-dependent mechanism described here for two types of developing cells provides the intriguing possibility that significant rises of Ca2+ may occur in specific cellular micro-domains of the spontaneously pacing cell during diastolic depolarization, prior to activation of upstroke of the action potential (Figs. 2 & 4) that may in turn contribute to slow diastolic depolarization of the membrane. This mechanism might be somewhat different from that described for the adult SA-nodal cells where voltage-gated channels are thought to play a mandatory role [7, 18, 49]. It remains to be explored whether these differences are associated with the developmental stages of the examined cells or experimental approaches.

4.4. Nature of Ca2+ pools supporting the spontaneous rhythmic beating

The findings that tetracaine and thapsigargin suppressed the rhythmic beating in both hiPS-CM and rN-CM, (Figs. 10 & 11) suggests Ca2+ release from the SR is critical in generating the rhythmic beating. Somewhat less expected were the rapid and reversible suppressive effects of small (50-100nM) and short exposures to mitochondrial un-coupler FCCP on the rhythmic activity (Figs. 12 & 13). Since FCCP also suppressed the rate of relaxation of caffeine-triggered Ca2+-transients (Figs. 12 & 14) as it inhibited the mitochondrial Ca2+ signals associated with spontaneous pacing (Figs. 12 & 13), the data suggests a critical role for mitochondria in spontaneous pacing. The mitochondrial imaging experiments with mitycam-E31Q probe, suggesting that the peri-nuclear population of mitochondria release Ca2+ as the peripheral mitochondria take up Ca2+ (Fig. 13, spontaneous beating and Fig. 14, caffeine application), were somewhat surprising, but do provide an intriguing possibility that may couple the mitochondrial ATP production to the rhythmic Ca2+ signaling and spontaneous beating. It is not as yet clear whether Ca2+ sequestered by mitochondrial is re-released directly into the cytosol or is transferred via specialized SR-mitochondrial junctions into the SR, and thereby modulating spontaneous beating. Our data clearly provide some support for mitochondrial Ca2+ release (Figs. 12-14), but the release mechanism remains unclear, though proposed candidates range from mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), and mNCX, to mRyR1 [50-52].

4.5. Physiological implications

Rhythmic activity in the adult mammalian heart originates from the SA-nodal cells. The morphology of SA-nodal cells differs sharply from their neighboring atrial and ventricular cells. They are smaller, ~20pF vs. 70-250pF for atrial and ventricular cells, with large surface to volume ratios, allowing for released Ca2+ to produce larger local Ca2+ concentrations, activating thereby larger inward INCX. Spontaneously beating rNCM and hiPS-CM are similarly small (~20pF), with large surface/volume ratios, and robust Ca2+ releases generating large INCX (Figs. 1-5, 7-13). Interestingly, unlike hiPS-CM, rN-CM do not express If, yet have higher pacing frequency, and otherwise are indistinguishable from hiPS-CM electrophysiologically, supporting the idea of minor role for If in spontaneous pacing of developing cardiomyocytes

Our studies provide insight into the mechanism that sets the “Ca2+ oscillator” in developing cardiomyocytes. Clearly depletion of Ca2+ content of SR, using caffeine or thapsigargin (Fig. 11), or blocking the RyRs (Fig. 10) stops the rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations, implicating the SR Ca2+ release to be critical in initiation of rhythmic beating. More intriguing, however, is the finding that short exposures of 50nM FCCP, reported to enhance oxidative metabolism, but not to depolarize the mitochondria or reduce ATP levels [30], consistently blocked the rhythmic activity rapidly and reversibly. Since the drug prolonged the rate of re-uptake of Ca2+ of spontaneously activated or caffeine-triggered Ca2+ transients (Fig. 12), it is likely that mitochondria have a critical role in rhythmic Ca2+-cycling thus modulating pacemaker activity in developing myocytes. We suggest that a cross-talk between SR and mitochondria sets the rhythmic cycle of Ca2+ release and re-uptake that results in cyclic activation of NCX to generate the inward current necessary to depolarize the myocyte at voltages beyond the activation voltage of If (Fig. 7). This possibility is strongly supported by the perforated patch and current-clamped experiments where the pacing cell generates significant rises of Ca2+ in specific cellular micro-domains prior to the upstroke of the action potential at −50mV, see (Fig. 2).

Experiments using mitycam-infected cells show diversity in mitochondrial populations vis-à-vis Ca2+ release and uptake. In this respect FCCP was effective in suppressing both the mitochondrial release and uptake signals as it suppressed the spontaneous beating and INCX accompanying them (Fig. 13). It is likely that this diversity in Ca2+-signaling of different mitochondrial populations serves as an additional oscillatory mechanism contributing to spontaneous pacing. Whether the processes that generate spontaneous pacing are also coupled to the energy producing mechanisms remains to be explored. This possibility may reinforce the notion that Ca2+ signaling parameters are relevant to normal and abnormal cardiac impulse formation where mitochondrial dysfunction may play a critical role in pathologies like arrhythmias and dilated cardiomyopathy [53].

4.6. Conclusions

Regionally diverse mitochondrial Ca2+-signaling, in addition to RyR2/NCX co-activation, may provide the critical negative feedback mechanism that initiates and regulates spontaneous beating in developing cardiomyocytes, independent of If-channels.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Myocytes derived from newborn rat heart & human induced pluripotent stem cells pace spontaneously

Ca2+-mediated pacing mechanisms are similar in both developing cell types

Pacing depends on activation of INCX & Ca2+-transients, but not on If and acute ICa block & Vm change

Regionally diverse mitochondrial Ca2+ signals may initiate and regulate pacing in both cell types

Bullet.

Ca2+ release from SR and mitochondria, not If, controls beating in developing cardiomyocytes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Naohiro Yamaguchi and Sara Pahlavan for constructing the FKBP-linked GCamP6 Ca2+ probe and making it available to us. This study was supported by grants to MM (NIH R01 HL15162 and R01 HL107600).

Abbreviations

- HCN channel

hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel

- hiPS-CM

cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells

- If

“funny” current through HCN channel

- INCX

Na+-Ca2+ exchanger current

- miPS-CM

cardiomyocytes derived from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells

- NCX

Na+-Ca2+ exchanger

- rN-CM

rat neonatal cardiomyocytes

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

Dr. Xiao-Hua Zhang works in the laboratories of the Cardiac Signaling center in Charleston, South Carolina, where she performed almost all the reported voltage-clamp and Ca2+ imaging experiments and has had a leading role in the analysis of data and preparation of the manuscript .

Dr. Hua Wei works in the laboratories of the Cardiac Signaling center in Charleston, South Carolina, where he has generated and maintenaned of hiPS-CM and miPS-CM cultures.

Dr. Tomo Šarić works at the University of Cologne, Germany, where he was instrumental in transfecting somatic human cells with pluripotency genes and guiding their differentiation to a stable cardiac phenotype.

Dr. Jürgen Hescheler works at the University of Cologne, Germany, where he was instrumental instrumental in transfecting somatic human cells with pluripotency genes and guiding their differentiation to a stable cardiac phenotype.

Dr. Lars Cleemann works in the laboratories of the Cardiac Signaling Center in Charleston, South Carolina, USA, where he took part in the instrumentation and experimentation. He has played a major role in formalizing and executing the evaluation of data and their graphic presentation in figures and in the preparation of the final manuscript.

Dr. Martin Morad works in the laboratories of the Cardiac Signaling Center in Charleston, South Carolina, USA. He played a major role in the conception and design of the experiments and in the drafting of the manuscript. He has supervised the project and taken part in the analysis of and evaluation of data.

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Maylie J, Morad M, Weiss J. A study of pace-maker potential in rabbit sino-atrial node: measurement of potassium activity under voltage-clamp conditions. J Physiol. 1981;311:161–178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yanagihara K, Irisawa H. Inward current activated during hyperpolarization in the rabbit sinoatrial node cell. Pflugers Arch. 1980;385:11–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00583909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown H, Difrancesco D. Voltage-clamp investigations of membrane currents underlying pace-maker activity in rabbit sino-atrial node. J Physiol. 1980;308:331–351. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature. 1998;393:587–591. doi: 10.1038/31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi W, Wymore R, Yu H, Wu J, Wymore RT, Pan Z, Robinson RB, Dixon JE, McKinnon D, Cohen IS. Distribution and prevalence of hyperpolarization-activated cation channel (HCN) mRNA expression in cardiac tissues. Circ Res. 1999;85:e1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju YK, Allen DG. Intracellular calcium and Na+-Ca2+ exchange current in isolated toad pacemaker cells. J Physiol. 1998;508(Pt 1):153–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.153br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdanov KY, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res. 2001;88:1254–1258. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders L, Rakovic S, Lowe M, Mattick PA, Terrar DA. Fundamental importance of Na+-Ca2+ exchange for the pacemaking mechanism in guinea-pig sino-atrial node. J Physiol. 2006;571:639–649. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vassalle M. Analysis of cardiac pacemaker potential using a “voltage clamp” technique. Am J Physiol. 1966;210:1335–1341. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.6.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble D, Tsien RW. The kinetics and rectifier properties of the slow potassium current in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1968;195:185–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trautwein W, Kassebaum DG. On the mechanism of spontaneous impulse generation in the pacemaker of the heart. J Gen Physiol. 1961;45:317–330. doi: 10.1085/jgp.45.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai R, Hagiwara N, Matsuda N, Kassanuki H, Hosoda S. Sodium--potassium pump current in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1996;490(Pt 1):51–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noble D, Noble SJ. A model of sino-atrial node electrical activity based on a modification of the DiFrancesco-Noble (1984) equations. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1984;222:295–304. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM. A coupled SYSTEM of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart's pacemaker. Circ Res. 2010;106:659–673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn TA, Kohl P. Mechano-sensitivity of cardiac pacemaker function: pathophysiological relevance, experimental implications, and conceptual integration with other mechanisms of rhythmicity. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2012;110:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belmonte S, Morad M. Shear fluid-induced Ca2+ release and the role of mitochondria in rat cardiac myocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:58–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeuchi A, Kim B, Matsuoka S. The mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, NCLX, regulates automaticity of HL-1 cardiomyocytes. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2766. doi: 10.1038/srep02766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaniv Y, Spurgeon HA, Lyashkov AE, Yang D, Ziman BD, Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. Crosstalk between mitochondrial and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling modulates cardiac pacemaker cell automaticity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown DA, O'Rourke B. Cardiac mitochondria and arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:241–249. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinogradova TM, Zhou YY, Maltsev V, Lyashkov A, Stern M, Lakatta EG. Rhythmic ryanodine receptor Ca2+ releases during diastolic depolarization of sinoatrial pacemaker cells do not require membrane depolarization. Circ Res. 2004;94:802–809. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122045.55331.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams GS, Boyman L, Chikando AC, Khairallah RJ, Lederer WJ. Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10479–10486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300410110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang M, Jiang L, Monticone RE, Lakatta EG. Proinflammation: the key to arterial aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saric T, Halbach M, Khalil M, Er F. Induced pluripotent stem cells as cardiac arrhythmic in vitro models and the impact for drug discovery. Expert opinion on drug discovery. 2014;9:55–76. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2014.863275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta MK, Illich DJ, Gaarz A, Matzkies M, Nguemo F, Pfannkuche K, Liang H, Classen S, Reppel M, Schultze JL, Hescheler J, Saric T. Global transcriptional profiles of beating clusters derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are highly similar. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fatima A, Xu G, Shao K, Papadopoulos S, Lehmann M, Arnaiz-Cot JJ, Rosa AO, Nguemo F, Matzkies M, Dittmann S, Stone SL, Linke M, Zechner U, Beyer V, Hennies HC, Rosenkranz S, Klauke B, Parwani AS, Haverkamp W, Pfitzer G, Farr M, Cleemann L, Morad M, Milting H, Hescheler J, Saric T. In vitro modeling of ryanodine receptor 2 dysfunction using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28:579–592. doi: 10.1159/000335753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang XH, Haviland S, Wei H, Saric T, Fatima A, Hescheler J, Cleemann L, Morad M. Ca2+ signaling in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (iPS-CM) from normal and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT)-afflicted subjects. Cell Calcium. 2013;54:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haviland S, Cleemann L, Kettlewell S, Smith GL, Morad M. Diversity of mitochondrial Ca(2)(+) signaling in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes: evidence from a genetically directed Ca(2)(+) probe, mitycam-E31Q. Cell Calcium. 2014;56:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fedorov VV, Lozinsky IT, Sosunov EA, Anyukhovsky EP, Rosen MR, Balke CW, Efimov IR. Application of blebbistatin as an excitation-contraction uncoupler for electrophysiologic study of rat and rabbit hearts. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan JP, Berry RG, Baghai M, Duchen MR, Shattock MJ. FCCP is cardioprotective at concentrations that cause mitochondrial oxidation without detectable depolarisation. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janowski E, Berrios M, Cleemann L, Morad M. Developmental aspects of cardiac Ca(2+) signaling: interplay between RyR- and IP(3)R-gated Ca(2+) stores. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1939–1950. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00607.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mummery C, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Doevendans P, Spijker R, van den Brink S, Hassink R, van der Heyden M, Opthof T, Pera M, de la Riviere AB, Passier R, Tertoolen L. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes: role of coculture with visceral endoderm-like cells. Circulation. 2003;107:2733–2740. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068356.38592.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halbach M, Peinkofer G, Baumgartner S, Maass M, Wiedey M, Neef K, Krausgrill B, Ladage D, Fatima A, Saric T, Hescheler J, Muller-Ehmsen J. Electrophysiological integration and action potential properties of transplanted cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:432–440. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubach M, Adelmann R, Haustein M, Drey F, Pfannkuche K, Xiao B, Koester A, Udink ten Cate FE, Choi YH, Neef K, Fatima A, Hannes T, Pillekamp F, Hescheler J, Saric T, Brockmeier K, Khalil M. Mesenchymal stem cells and their conditioned medium improve integration of purified induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte clusters into myocardial tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:643–653. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleemann L, Wang W, Morad M. Two-dimensional confocal images of organization, density, and gating of focal Ca2+ release sites in rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noma A, Morad M, Irisawa H. Does the “pacemaker current” generate the diastolic depolarization in the rabbit SA node cells? Pflugers Arch. 1983;397:190–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00584356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bucchi A, Baruscotti M, DiFrancesco D. Current-dependent block of rabbit sino atrial node I(f) channels by ivabradine. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:1–13. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurata Y, Hisatome I, Imanishi S, Shibamoto T. Roles of L-type Ca2+ and delayed-rectifier K+ currents in sinoatrial node pacemaking: insights from stability and bifurcation analyses of a mathematical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2804–2819. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01050.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itzhaki I, Rapoport S, Huber I, Mizrahi I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Arbel G, Schiller J, Gepstein L. Calcium handling in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zahanich I, Sirenko SG, Maltseva LA, Tarasova YS, Spurgeon HA, Boheler KR, Stern MD, Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA. Rhythmic beating of stem cell-derived cardiac cells requires dynamic coupling of electrophysiology and Ca cycling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adachi-Akahane S, Lu L, Li Z, Frank JS, Philipson KD, Morad M. Calcium signaling in transgenic mice overexpressing cardiac Na(+)-Ca2+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:717–729. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mason CA, Ferrier GR. Tetracaine can inhibit contractions initiated by a voltage-sensitive release mechanism in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999;519(Pt 3):851–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0851n.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaper J, Meiser E, Stammler G. Ultrastructural morphometric analysis of myocardium from dogs, rats, hamsters, mice, and from human hearts. Circ Res. 1985;56:377–391. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drago I, De Stefani D, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake contributes to buffering cytoplasmic Ca2+ peaks in cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12986–12991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210718109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kettlewell S, Cabrero P, Nicklin SA, Dow JA, Davies S, Smith GL. Changes of intra-mitochondrial Ca2+ in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes examined using a novel fluorescent Ca2+ indicator targeted to mitochondria. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:891–901. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maylie J, Morad M. Ionic currents responsible for the generation of pace-maker current in the rabbit sino-atrial node. J Physiol. 1984;355:215–235. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verkerk AO, Wilders R, van Borren MM, Peters RJ, Broekhuis E, Lam K, Coronel R, de Bakker JM, Tan HL. Pacemaker current (I(f)) in the human sinoatrial node. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2472–2478. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stern MD, Maltseva LA, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ, Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA. Hierarchical clustering of ryanodine receptors enables emergence of a calcium clock in sinoatrial node cells. J Gen Physiol. 2014;143:577–604. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gunter TE, Buntinas L, Sparagna G, Eliseev R, Gunter K. Mitochondrial calcium transport: mechanisms and functions. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:285–296. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 2004;427:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altschafl BA, Beutner G, Sharma VK, Sheu SS, Valdivia HH. The mitochondrial ryanodine receptor in rat heart: a pharmaco-kinetic profile. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1784–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenberg P. Mitochondrial dysfunction and heart disease. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.