Medically attended acute respiratory illnesses laboratory-confirmed as influenza were more severe and resulted in more missed work hours and productivity loss than illnesses not confirmed as influenza. Modest reductions in illness severity for vaccinated influenza cases were observed.

Keywords: medically attended acute respiratory illness, medically attended influenza, illness severity, work productivity, vaccine effectiveness

Abstract

Background. Influenza causes significant morbidity and mortality, with considerable economic costs, including lost work productivity. Influenza vaccines may reduce the economic burden through primary prevention of influenza and reduction in illness severity.

Methods. We examined illness severity and work productivity loss among working adults with medically attended acute respiratory illnesses and compared outcomes for subjects with and without laboratory-confirmed influenza and by influenza vaccination status among subjects with influenza during the 2012–2013 influenza season.

Results. Illnesses laboratory-confirmed as influenza (ie, cases) were subjectively assessed as more severe than illnesses not caused by influenza (ie, noncases) based on multiple measures, including current health status at study enrollment (≤7 days from illness onset) and current activity and sleep quality status relative to usual. Influenza cases reported missing 45% more work hours (20.5 vs 15.0; P < .001) than noncases and subjectively assessed their work productivity as impeded to a greater degree (6.0 vs 5.4; P < .001). Current health status and current activity relative to usual were subjectively assessed as modestly but significantly better for vaccinated cases compared with unvaccinated cases; however, no significant modifications of sleep quality, missed work hours, or work productivity loss were noted for vaccinated subjects.

Conclusions. Influenza illnesses were more severe and resulted in more missed work hours and productivity loss than illnesses not confirmed as influenza. Modest reductions in illness severity for vaccinated cases were observed. These findings highlight the burden of influenza illnesses and illustrate the importance of laboratory confirmation of influenza outcomes in evaluations of vaccine effectiveness.

Seasonal influenza epidemics cause significant excess morbidity and mortality in the United States each year [1, 2]. The total annual economic burden of influenza in the United States has been estimated to exceed $87 billion; more than $10 billion of which is attributed to direct costs of medical treatment and more than $6 billion to lost productivity from illness [3]. Past estimates of burden, particularly in terms of lost productivity, have typically used nonspecific outcomes such as acute respiratory illness (ARI) or influenza-like illness (ILI) based on symptomatic case definitions [4–6]. With the development of real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays, we are now able to identify precisely those illnesses that are potentially vaccine preventable. We can also compare the severity of illnesses that are laboratory-confirmed as influenza to those that are not.

To reduce the burden of influenza illness, annual influenza vaccination is currently recommended for all persons aged ≥6 months [7]. Vaccine effectiveness (VE) may vary from year to year due to the age and health status of vaccine recipients, the predominant circulating virus strain, and the antigenic match between vaccine and circulating strains [8–12]. To monitor variation in VE, multiple centers in the United States have collaborated each year since the 2008–2009 season through the US Flu VE Network [8–11]. This network examines the effectiveness of influenza vaccines in preventing medically attended acute respiratory illnesses (MAARI) caused by influenza. Using a test-negative analytic approach, VE is estimated by comparing the vaccination status of those who test positive for influenza with those who test negative [13, 14]. Generally, these studies have indicated moderate VE (47%–61%), with lower effectiveness against influenza A (H3N2) viruses compared with A (H1N1) and type B strains, and variation in effectiveness by age group [8–11].

Most evaluations of VE have focused on the benefit of primary prevention of influenza illness. Less clear is whether influenza vaccines are effective in reducing the severity of influenza illnesses and the burden of lost productivity among vaccine failures—those infected with influenza despite vaccination. Studies that have examined influenza-related illness severity and the potential benefit of vaccination in modifying illness have generally reported equivocal results or modest reductions in severity among vaccine failures [15–20]. Evaluations of the negative effect of acute respiratory illnesses on work productivity have not directly examined the potential value of vaccination in reducing productivity loss [4] or laboratory-confirmed illnesses as influenza [4–6].

We examined illness severity, time to recovery, and work productivity loss among working adults with MAARI who participated in the US Flu VE Network study during the 2012–2013 influenza season. We compared these outcomes for MAARI subjects with and without laboratory-confirmed influenza and by influenza vaccination status among influenza-positive subjects. The 2012–2013 season was characterized as moderately severe, with simultaneous cocirculation of influenza A (H3N2) and type B strains; overall adjusted VE estimates from the network indicated vaccine was 49% (95% confidence interval [CI], 43, 55) effective in reducing the risk of MAARI caused by influenza [9].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Enrollment and Follow-up

The original study enrolled 6766 adults and children seeking care for ARI at ambulatory care facilities, including urgent care clinics affiliated with 5 network centers [9]. The centers included the Group Health Cooperative, Seattle, Washington; Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation, Marshfield, Wisconsin; University of Michigan School of Public Health partnered with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Henry Ford Health Systems, Detroit, Michigan; University of Pittsburgh Schools of Health Sciences partnered with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Scott & White Healthcare, Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine, Temple, Texas. The institutional review boards at participating network centers approved the study.

Briefly, patients seeking care for ARI, characterized by cough of ≤7 days duration, were interviewed regarding their illness, had throat and nasal swab specimens collected for virus identification, and were asked to complete a follow-up survey 7 days after enrollment. Enrollment data included subject demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), plus subjective assessments of health status, both general prior to ARI (1 = excellent … 5 = poor) and current (0 = worst … 100 = best), current activity relative to usual (0 = unable to perform usual activities … 9 = able to perform usual activities), current sleep quality relative to normal (0 = worst quality of sleep … 9 = normal pre-illness quality of sleep), social position relative to other US households (1 = worst off … 9 = best off) [21], and current smoking status. Respiratory specimens collected at enrollment were combined and tested for influenza virus identification at network laboratories by means of RT-PCR, the most sensitive and specific method of influenza identification currently available [17]. The RT-PCR primers, probes, and testing protocol were developed and provided by the Influenza Division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Follow-up surveys requested information on timing of return to normal activities, employment status and missed work hours due to illness, and a subjective assessment of the degree to which illness impeded work productivity (0 = no effect on work … 10 = completely prevented from working). Measures of illness severity, social position, and work productivity loss ascertained at enrollment or at follow-up were adapted from previously used instruments (Supplementary Table 1) [21–25].

Influenza vaccination for the 2012–2013 season was documented from medical records or immunization registries; subjects without evidence were considered unvaccinated. Subjects were defined as high risk if they had medical record documentation during the year before enrollment of health conditions that increased their risk of influenza complications [7]. Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) was calculated from self-reported information or medical record–determined weight and height and categorized as under or normal weight, overweight, and obese. Treatment with influenza antiviral medications was defined from the medical record; illnesses in subjects with prescription of antiviral medications within 2 days of study enrollment were considered treated.

Analysis Subset: Inclusion Criteria and Variables

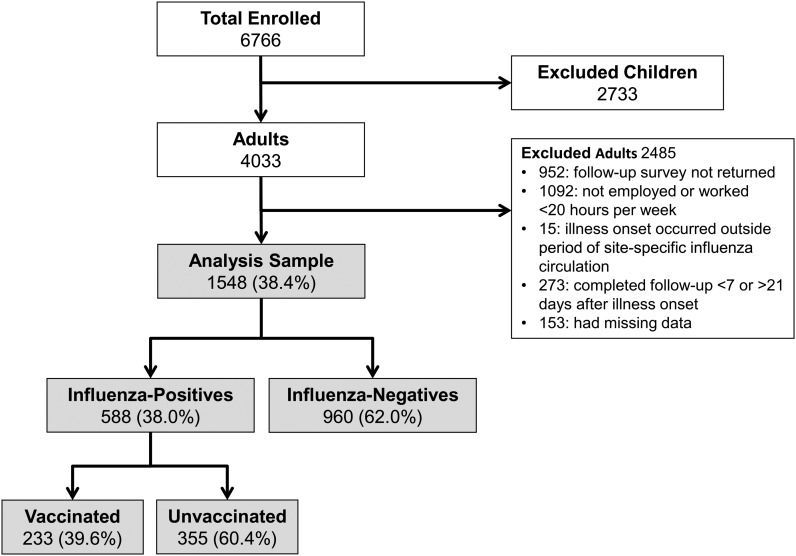

There were 4033 adults in the overall study population, of which 1548 (38%) met the criteria for inclusion in this analysis (see Figure 1). Inclusion criteria included completing the follow-up survey between 7 and 21 days after illness onset, being employed and working at least 20 hours per week, plus having complete data on defined exposures (laboratory-confirmed influenza status and documented influenza vaccination status) and defined outcomes (at enrollment: provided subjective assessments of current health status, current activity status, and current sleep quality; at follow-up: provided information on timing of return to normal activities, the number of work hours missed due to illness, and a subjective assessment of work productivity during illness).

Figure 1.

Total enrollment and number of subjects included in analyses of illness severity and work productivity loss: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013).

Illness severity was represented by subjective assessments of current health status and reported current activity and sleep quality scores, reported at the enrollment visit, plus the timing of return to normal activities. Work productivity loss was estimated by the total number of missed work hours due to illness and the subjective assessment of work productivity during illness; both were reported as part of the follow-up survey.

Statistical Methods

We examined differences in characteristics and outcomes by laboratory-confirmed influenza status among the entire analysis set and separately by influenza vaccination status among influenza-positive subjects (ie, cases). For each influenza and vaccination status group, means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges were estimated for continuous symmetrically distributed or continuous asymmetrically distributed variables, respectively. Proportions were calculated across categorical variables. Statistical significance of differences was assessed by χ2 test for categorical variables or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables.

Adjusted associations of influenza status with outcomes and vaccination status among influenza cases with outcomes were modeled in 2 ways. Reported current health status, current activity, current sleep quality, and work productivity scores were modeled using linear regression with estimation of mean differences. The total number of missed work hours due to illness was modeled using negative binomial regression with calculation of percent differences. All outcomes were modeled with the generalized estimating equation method; models were adjusted for the number of days between illness onset and the outcome (measured at either enrollment or follow-up) and for within-site dependencies by treating site as a correlated cluster. Models were also adjusted for the following covariates: general health prior to illness, age, sex, race/ethnicity, subjective social status, BMI category, current smoking status, high-risk health status, antiviral treatment, and biweekly calendar time of illness onset. The model of missed work hours was adjusted for expected weekly work hours. Differences in the rate of return to normal activities were examined using Kaplan–Meier plots and tested using the log-rank test; subjects who had not yet returned to normal activities were censored at the time of follow-up survey completion. An alpha of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance in all tests. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (release 9.3; SAS Institute); R statistical program and packages were used for the creation of plots [26].

RESULTS

Illness Severity and Work Productivity by Influenza Test Status

The analysis subset included 1548 working adult subjects with MAARI. 588 (38%) subjects tested positive for influenza (ie, cases), including 405 with influenza type A (primarily A/H3N2) and 184 with type B; 960 (62%) tested negative (ie, noncases). Distributions and comparisons of characteristics by influenza status are presented in Table 1. The mean age of included subjects was 44 years, 65% were female, 85% were white non-Hispanic, 33% had high-risk health conditions, 46% were classified as obese, 14% were current smokers, and 68% reported their health status prior to illness as excellent/very good. On average, subjects rated their subjective social position as 6.1 on a scale of 1 (worst off) to 9 (best off) [21, 27]. As expected, influenza cases were significantly less likely than noncases to have documented evidence of influenza vaccine receipt (40% vs 54%; P < .001). Overall, 141 (9%) subjects had antiviral treatment prescribed for their illness, including 17% of influenza cases and 4% of noncases (P < .001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1548 Working Adults With Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness by Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Status: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013)

| Characteristic | Total N = 1548 | Influenza Test-Positive Cases n = 588 (38%) |

Influenza Test-Negative Noncases n = 960 (62%) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD), range, 18–83 | 44.2 (13.1) | 45.1 (13.1) | 43.7 (13.1) | .07a |

| Subjective social position, mean (SD), range, 1–9 | 6.1 (1.4) | 6.0 (1.4) | 6.1 (1.4) | .28a |

| Influenza vaccinated, N (%)b,c | 750 (48.4) | 233 (39.6) | 517 (53.9) | <.001d |

| Sex, N (%)b | <.001d | |||

| Female | 1007 (65.1) | 353 (60.0) | 654 (68.1) | |

| Male | 541 (34.9) | 235 (40.0) | 306 (31.9) | |

| Race, N (%)b | .63d | |||

| White | 1311 (84.7) | 498 (84.7) | 813 (84.7) | |

| Black | 66 (4.3) | 22 (3.7) | 44 (4.6) | |

| Hispanic | 73 (4.7) | 32 (5.4) | 41 (4.3) | |

| Other | 98 (6.3) | 36 (6.1) | 62 (6.5) | |

| Body mass index category, N (%)b,e | .59d | |||

| Under/Normal weight | 361 (23.3) | 130 (22.1) | 231 (24.1) | |

| Overweight | 483 (31.2) | 182 (31.0) | 301 (31.4) | |

| Obese | 704 (45.5) | 276 (46.9) | 428 (44.6) | |

| High-risk medical condition, N (%)b | 516 (33.3) | 196 (33.3) | 320 (33.3) | 1.00d |

| Current smoker, N (%)b | 222 (14.3) | 84 (14.3) | 138 (14.4) | .96d |

| General health prior to illness, N (%)b | .31d | |||

| Excellent/Very good | 1057 (68.3) | 409 (69.6) | 648 (67.5) | |

| Good | 404 (26.1) | 142 (24.1) | 262 (27.3) | |

| Fair/Poor | 87 (5.6) | 37 (6.3) | 50 (5.2) | |

| Antiviral treatment prescribed, N (%)b,f | 141 (9.1) | 99 (16.8) | 42 (4.4) | <.001d |

| Ever stopped normal activities, N (%)b | 1364 (88.1) | 549 (93.4) | 815 (84.9) | <.001d |

| Any work productivity loss, N (%)b | 1463 (94.5) | 556 (94.6) | 907 (94.5) | .95d |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Corresponding 2-sided P values calculated by Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables.

b Percentages shown are by column totals.

c A subject was considered vaccinated given documented evidence, in the medical record or immunization registry, of vaccine receipt 14 or more days prior to the onset of illness.

d Corresponding 2-sided P values calculated by Pearson χ2 test of independence for categorical variables.

e Body mass index categories from the World Health Organization website: who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

f Illnesses in subjects with prescription of antiviral medications within 2 days of study enrollment were considered treated.

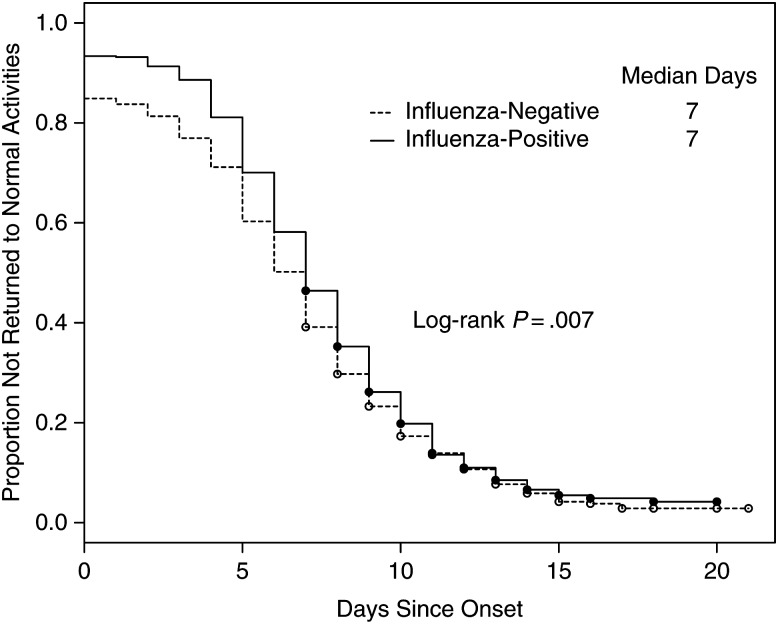

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and results from adjusted models that examined illness severity and work productivity by influenza status. Overall, current health status at enrollment was subjectively assessed as 55 (standard deviation = 20.9) on a scale of 0 (worst) to 100 (best), with significantly lower current health status reported by influenza cases compared with noncases (50.0 vs 57.4; mean difference, −7.3 [95% CI, −8.7, −5.9]; P < .001). Similarly, ability to perform current activities and current sleep quality were self-assessed as significantly lower for influenza cases compared with noncases. Influenza cases reported missing 45% more work hours (20.5 vs 15.0 missed hours; P < .001) than noncases and subjectively assessed their work productivity as impeded to a greater degree (6.0 vs 5.4; P < .001); 95% of both cases and noncases reported some degree of work productivity loss (scored as ≥1 vs 0). Overall, 88% of subjects reported ever stopping their normal activities due to their illness, including 93% of influenza cases and 85% of noncases (P < .001). Figure 2 examines differences in the rate of return to normal activities for cases and noncases. Because noncases were less likely to ever stop normal activities, the hazard function for time to return to normal activities was significantly lower for noncases (P = .01); however, the median duration of illness was 7 days for both cases and noncases.

Table 2.

Self-Assessments of Measures of Illness Severity and Work Productivity Loss Among 1548 Working Adults With Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness by Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Status: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013)

| Outcome Measure | Total N = 1548 | Influenza Test-Positive Cases n = 588 (38%) |

Influenza Test-Negative Noncases n = 960 (62%) |

Unadjusted P Value |

Adjusteda,b

Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

Adjusteda,b

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current health score at enrollment, mean (SD) | 54.6 (20.9) | 50.0 (21.4) | 57.4 (20.1) | <.001 | −7.3 (−8.7, −5.9) | <.001 |

| Current activity score at enrollment, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.5) | 4.4 (2.4) | 5.5 (2.4) | <.001 | −1.1 (−1.4, −.8) | <.001 |

| Sleep quality score at enrollment, mean (SD) | 4.1 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.5) | 4.3 (2.5) | <.001 | −.7 (−.9, −.5) | <.001 |

| Work productivity loss during illness, mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.8) | 6.0 (2.8) | 5.4 (2.7) | <.001 | 0.8 (.5, 1.04) | <.001 |

| Missed work hours during illness, median (interquartile range), range, 0–150 | 16.0 (8–28) | 20.5 (12–32) | 15.0 (4–24) | <.001 | 45.2% (26.7, 66.5) | <.001 |

Scales: Current health status (0 = worst … 100 = best); current activity relative to usual (0 = unable to perform usual activities … 9 = able to perform usual activities); current sleep quality relative to normal (0 = worst quality of sleep … 9 = normal pre-illness quality of sleep); degree to which illness impeded work productivity (0 = no effect on work … 10 = completely prevented from working).

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Adjusted estimates are mean differences calculated in linear regression (generalized estimating equation) models for the outcomes current health score, current activity score, sleep quality score, and work productivity score, and percent differences calculated in negative binomial regression models for missed work hours during illness. Models were adjusted for within-site dependencies by treating site as a correlated cluster.

b All adjusted models included the following covariates: general health status prior to illness, age, sex, race, subjective social position, body mass index category, current smoking status, presence of any high-risk health condition, antiviral treatment, and biweekly calendar time of illness onset. Models of current health, current activity, and sleep quality were also adjusted for time from illness onset to enrollment; models of work productivity and missed work time were also adjusted for time from illness onset to follow-up survey completion. Model of missed work time was also adjusted for expected work hours per week.

Figure 2.

Days from illness onset to return to normal activities comparing influenza-positive cases and influenza-negative noncases among working adults: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013).

Illness Severity and Work Productivity by Influenza Vaccination Status Among Influenza Cases

Distributions and comparisons of characteristics by vaccination status among influenza cases are presented in Table 3. Forty percent of influenza cases had documented evidence of influenza vaccine receipt. Vaccinated cases were significantly older than unvaccinated cases (48 vs 43 years; P < .001), were more likely to be female, and were more likely to have 1 or more high-risk health conditions. Vaccinated cases were also more likely to have antiviral treatment prescribed for their illness (20.6% vs 14.4%; P = .05).

Table 3.

Characteristics of 588 Working Adults With Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness Laboratory-Confirmed as Influenza by Vaccination Status: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013)

| Characteristic | Influenza Test-Positive Cases Vaccinateda n = 233 (40%) | Influenza Test-Positive Cases Not Vaccinated n = 355 (60%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD), range, 18–83 | 47.8 (13.1) | 43.3 (12.8) | <.001b |

| Subjective social position, mean (SD), range, 1–9 | 6.1 (1.5) | 6.0 (1.4) | .14b |

| Sex, N (%)c | .01d | ||

| Female | 155 (66.5) | 198 (55.8) | |

| Male | 78 (33.5) | 157 (44.2) | |

| Race, N (%)c | .31d | ||

| White | 204 (87.6) | 294 (82.8) | |

| Black | 5 (2.1) | 17 (4.8) | |

| Hispanic | 11 (4.7) | 21 (5.9) | |

| Other | 13 (5.6) | 23 (6.5) | |

| Body mass index category, N (%)c,e | .27d | ||

| Under/Normal weight | 45 (19.3) | 85 (23.9) | |

| Overweight | 70 (30.0) | 112 (31.5) | |

| Obese | 118 (50.6) | 158 (44.5) | |

| High-risk medical condition, N (%)c | 111 (47.6) | 85 (23.9) | <.001d |

| Current smoker, N (%)c | 22 (9.4) | 62 (17.5) | .01d |

| General health prior to illness, N (%)c | .18d | ||

| Excellent/Very good | 152 (65.2) | 257 (72.4) | |

| Good | 65 (27.9) | 77 (21.7) | |

| Fair/Poor | 16 (6.9) | 21 (5.9) | |

| Antiviral treatment prescribed, N (%)c,f | 48 (20.6) | 51 (14.4) | .05d |

| Ever stopped normal activities, N (%)c | 220 (94.4) | 329 (92.7) | .41d |

| Any work productivity loss, N (%)c | 221 (94.8) | 335 (94.4) | .80d |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a A subject was considered vaccinated given documented evidence, in the medical record or immunization registry, of vaccine receipt 14 or more days prior to the onset of illness.

b Corresponding 2-sided P values calculated by Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables.

c Percentages shown are by column totals.

d Corresponding 2-sided P values calculated by Pearson χ2 test of independence for categorical variables.

e Body mass index categories from the World Health Organization website: who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

f Illnesses in subjects with prescription of antiviral medications within 2 days of study enrollment were considered treated.

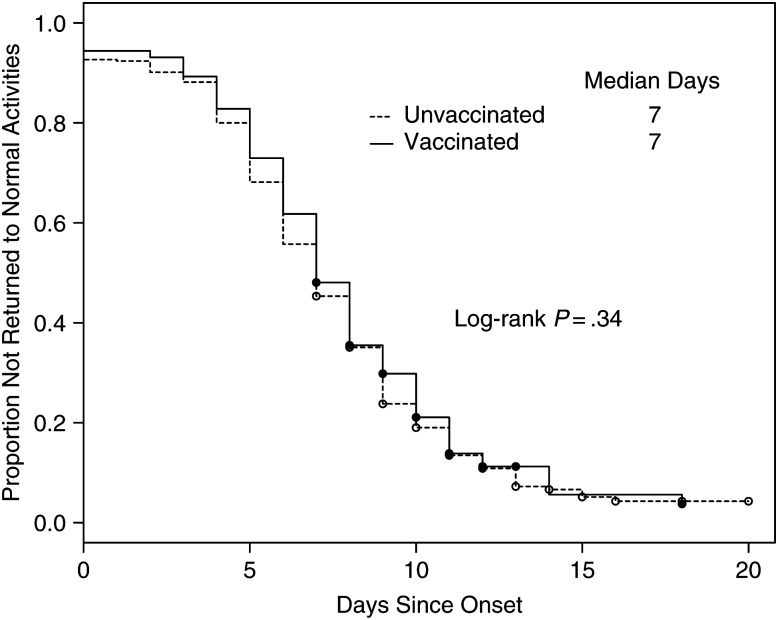

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics and results from adjusted models that examined illness severity and work productivity by vaccination status. Current health status at enrollment was subjectively assessed as modestly, but significantly, better for vaccinated cases compared with unvaccinated cases (52.0 vs 48.6; mean difference, 3.7 [95% CI, .8, 6.6]; P = .01). Similarly, current activity relative to normal activity was scored as significantly better for vaccinated cases (4.6 vs 4.3; mean difference, 0.3 [95% CI, .01, .6]; P = .04). However, no significant modifications of sleep quality, number of work hours missed, or work productivity loss were noted for vaccinated subjects, nor were any differences noted in the proportion of subjects who ever stopped their normal activities (94.4% vs 92.7%; P = .41) or who reported some degree of work productivity loss (94.8 vs 94.4; P = .80). Figure 3 examines the rate of return to normal activities. Findings indicate that vaccinated and unvaccinated influenza cases did not differ in the timing of their return to normal (log-rank P = .34).

Table 4.

Self-Assessments of Measures of Illness Severity and Work Productivity Loss Among 588 Working Adults With Medically Attended Acute Respiratory Illness Laboratory-Confirmed as Influenza by Vaccination Status: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013)

| Outcome Measure | Influenza Test-Positive Cases Vaccinated n = 233 (40%) | Influenza Test-Positive Cases Not Vaccinated n = 355 (60%) | Unadjusted P Value | Adjusteda,b

Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

Adjusteda,b P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current health score at enrollment, mean (SD) | 52.0 (21.2) | 48.6 (21.5) | .04 | 3.7 (.8, 6.6) | .01 |

| Current activity score at enrollment, mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.5) | 4.3 (2.4) | .14 | 0.3 (.01, .6) | .04 |

| Sleep quality score at enrollment, mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.6 (2.5) | .55 | 0.1 (−.4, .6) | .68 |

| Work productivity loss during illness, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.7) | 6.1 (2.8) | .46 | −0.1 (−.5, .3) | .66 |

| Missed work hours during illness, median (interquartile range), range, 0–120 | 24 (12–32) | 20 (11–32) | .65 | −4.3% (−10.9, 2.80) | .23 |

Scales: Current health status (0 = worst … 100 = best); current activity relative to usual (0 = unable to perform usual activities … 9 = able to perform usual activities); current sleep quality relative to normal (0 = worst quality of sleep … 9 = normal pre-illness quality of sleep); degree to which illness impeded work productivity (0 = no effect on work … 10 = completely prevented from working).

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Adjusted estimates are mean differences calculated in linear regression (generalized estimating equation) models for the outcomes current health score, current activity score, sleep quality score, and work productivity score, and percent differences calculated in negative binomial regression models for missed work hours during illness. Models were adjusted for within-site dependencies by treating site as a correlated cluster.

b All adjusted models included the following covariates: general health status prior to illness, age, sex, race, subjective social position, body mass index category, current smoking status, presence of any high-risk health condition, antiviral treatment, and biweekly calendar time of illness onset. Models of current health, current activity, and sleep quality were also adjusted for time from illness onset to enrollment; models of work productivity and missed work time were also adjusted for time from illness onset to follow-up survey completion. Model of missed work time was also adjusted for expected work hours per week.

Figure 3.

Days from influenza illness onset to return to normal activities comparing vaccinated and unvaccinated working adults: US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (2012–2013).

DISCUSSION

Due to the substantial economic and personal burden of acute respiratory illnesses including influenza, there are clear benefits to be gained by effective prevention and treatment strategies [3–6]. Evidence indicates that current influenza vaccines provide moderate primary protection against symptomatic influenza illnesses, including medically attended influenza illnesses [8–12, 28]. Other evidence suggests benefits for vaccination against ARI or ILI; however, failure to laboratory-confirm outcomes as influenza may compromise these results [5, 6, 29]. In terms of post-infection outcomes, some evidence suggests that vaccine may modify the severity of influenza illnesses. For example, subjects in a randomized trial who were influenza infected despite receiving inactivated influenza vaccine were less likely than similar subjects who received placebo to seek medical care for their illnesses [17]. Similarly, vaccination was associated with reduction in symptom severity among older adults who sought medical care for an influenza infection [18] and with reduced likelihood of severe outcomes among older adults hospitalized with influenza [19]. However, other studies have found no statistically significant differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in terms of development of febrile influenza illness [20], subsequent hospital admission after influenza-associated outpatient visits [15], or likelihood of severe outcomes (eg, pneumonia) or length of stay among older adults hospitalized with influenza infection [16].

We examined illness severity and work productivity loss among working adults with MAARI. Illnesses that were laboratory-confirmed as influenza were subjectively assessed as more severe than illnesses not caused by influenza based on multiple measures. Absenteeism was a particularly sensitive marker, with influenza-positive cases missing 45% more work hours during their illness than those who were influenza negative. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies that indicated influenza illnesses were more likely to be medically attended than illnesses caused by other respiratory viruses [30, 31] and that those infected with influenza had higher illness severity scores than those with noninfluenza ARI [18].

We also examined illness severity and work productivity among laboratory-confirmed influenza cases by influenza vaccination status and found modest benefits for vaccination among vaccine failures. Specifically, self-assessments of current health and current activity status at enrollment (within ≤7 days of illness onset) were scored significantly better for vaccinated cases compared with unvaccinated cases; however, the clinical relevance of these small improvements is unclear. Work productivity while ill was not improved for vaccinated cases compared with unvaccinated cases, and there was no evidence of more rapid recovery for vaccinated cases. These results are generally consistent with previously noted studies that indicated that the effectiveness of vaccination in reducing severity of post-infection outcomes, if present, is modest [15–20].

The primary strength of this study was the use of a sensitive and specific RT-PCR test to laboratory-confirm outcomes. Most previous studies that examined the effects of influenza on work absence and productivity loss used nonspecific outcomes, potentially resulting in biased estimates [4–6]. In the current study, only 38% of illnesses (≤7 days duration with cough) identified during periods of known influenza circulation were laboratory-confirmed as influenza. Similarly, in a year-long surveillance study, only 21% of outpatient visits meeting case definitions for ARI or ILI were laboratory-confirmed as influenza [31]. These findings confirm that if a higher proportion of cases in previous studies using ARI or ILI in place of laboratory-confirmed outcomes had been assumed to represent influenza, the potential for influenza vaccines and antivirals to reduce the economic burden of ARI would have been overestimated [4–6]. Other strengths include use of documented evidence of vaccination and participant recruitment, with systematic screening, enrollment, and data collection at ambulatory care sites in multiple geographic areas. The current study was focused on adults employed at least half time and required data collection at enrollment and during illness recovery. Subjects who failed to return their follow-up survey were excluded, raising concerns of selection biases.

The questions used to measure work hours missed and productivity losses were inspired by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Instrument (WPAI) [25]. This survey instrument was initially developed to assess work absenteeism and productivity impairment over the past 7 days among persons with chronic conditions. The instrument has not previously been used to assess productivity loss associated with an acute illness of variable duration, and validity in this situation has not been evaluated. Similarly, instruments to measure illness severity were adapted from validated surveys (Supplementary Table 1), but validity of these versions has not been assessed. Because productivity could not be assessed over a uniform time period, as in the original WPAI, subjects were queried on the number of hours they were expected to work in a typical week and the number of work hours missed due to their respiratory illness. This strategy did not permit precise determination of the number of work hours that were at risk of absence or productivity loss during the period of illness. As a result, an overall assessment of total productivity loss, including absenteeism (the proportion of expected work time lost to absence due to illness) and presenteeism (the proportion of expected work time lost to decreased productivity when working while ill) [32], was not possible.

We found that laboratory-confirmed influenza illnesses were more severe and resulted in more missed work hours and productivity loss than medically attended illnesses not confirmed by RT-PCR as influenza. Additionally, we observed modest reductions in illness severity for influenza cases who were vaccinated. These findings confirm the potential value and economic benefit of vaccination and illustrate the importance of laboratory confirmation of influenza outcomes in evaluations of VE. Influenza vaccines that provide greater protective effectiveness are needed to take advantage of these potential benefits.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at (http://cid.oxfordjournals.org). Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copy edited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. This work was supported by the CDC through cooperative agreements with the University of Michigan (grant number U01 IP000474), Group Health Research Institute (grant number U01 IP000466), Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation (grant number U01 IP000471), University of Pittsburgh (grant number U01 IP000467), and Scott and White Healthcare (grant number U01 IP000473). At the University of Pittsburgh, the project was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR000005).

Potential conflicts of interest. R. K. Z. reports research grant support from Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, and Merck. M. G. reports research support from Medimmune, Novartis, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and consulting fees from BioCryst. M. P. N. reports research grant support from Pfizer and Merck. A. S. M. reports research grant support from Sanofi and consulting fees from Novartis and GSK. S. E. O. reports research grant support from Sanofi. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Thompson MG, Shay DK, Zhou H et al. Updated estimates of mortality associated with seasonal influenza through the 2006–2007 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:1057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 2004; 292:1333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molinari NAM, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 2007; 25:5086–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer LA, Rousculp MD, Johnston SS, Mahadevia PJ, Nichol KL. Effect of influenza-like illness and other wintertime respiratory illnesses on worker productivity: the Child and Household Influenza-Illness and Employee Function (CHIEF) study. Vaccine 2010; 32:453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichol KL, D'Heilly SJ, Greenberg ME, Ehlinger E. Burden of influenza-like illness and effectiveness of influenza vaccination among working adults aged 50–64 years. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keech M, Beardsworth P. The impact of influenza on working days lost. A review of the literature. Pharacoeconomics 2008; 26:911–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010; 59(RR-08):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohmit SE, Thompson MG, Petrie JG et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2011–2012 season: protection against each circulating virus and the effect of prior vaccination on estimates. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012–2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis 2014; 211:1529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flannery B, Thanker SN, Clippard J et al. Interim estimates of 2013–2014 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:137–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flannery B, Clippard J, Zimmerman RK et al. Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, January 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:10–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, De Serres G et al. Low 2012–2013 influenza vaccine effectiveness associated with mutation in the egg-adapted H3N2 vaccine strain not antigenic drift in circulating viruses. PLoS One 2014; 9:e92153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2013; 31:2165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foppa IM, Haber M, Ferdinands JM et al. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2013; 31:3104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLean HQ, Meece JK, Belongia EA. Influenza vaccination and risk of hospitalization among adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza illness. Vaccine 2014; 32:453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arriola CS, Anderson EJ, Baumbach J et al. Does influenza vaccination modify influenza disease severity? Data on older adults hospitalized with influenza during the 2012–2013 season in the United States. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1200–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Johnson E, Cross RT, Monto AS. Efficacy studies of influenza vaccines: effect of end points used and characteristics of vaccine failures. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:1309–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.VanWormer JJ, Sundaram ME, Meece JK, Belongia EA. A cross-sectional analysis of symptom severity in adults with influenza and other acute respiratory illnesses in the outpatient setting. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castilla J, Godoy P, Dominguez A et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing outpatient, inpatient and severe cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridgway JP, Bartlett AH, Garcia-Houchins S et al. Influenza among afebrile and vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1591–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh-Manoux A, Marmot M, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med 2005; 67:855–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2012_brfss.pdf Accessed 26 October 2015.

- 23.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20:1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborn RH, Hawthorne G, Papanicolaou M, Wegmueller Y. Measurement of rapid changes in health outcomes in people with influenza symptoms. J Drug Assess 2000; 3:205–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmaco Econ 1993; 4:353–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 26 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malosh R, Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Thompson MG, Aiello AE, Monto AS. Factors associated with influenza vaccine receipt in community dwelling adults and their children. Vaccine 2014; 32:1841–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito Y, Sumi H, Kato T. Evaluation of influenza vaccination in health care workers, using rapid antigen detection test. J Infect Chemother 2006; 12:70–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monto AS, Malosh RE, Petrie JG, Thompson MG, Ohmit SE. Frequency of acute respiratory illnesses and circulation of respiratory viruses in households with children over 3 surveillance seasons. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1792–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fowlkes A, Giorgi A, Erdman D et al. Viruses associated with acute respiratory infections and influenza-like illness among outpatients from the influenza incidence surveillance project, 2010–2011. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:1715–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dew K, Keefe V, Small K “Choosing” to work when sick: workplace presenteeism. Soc Sci Med 2005; 60:2273–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.