Abstract

Introduction

Fair distribution of hospital beds across various regions is a controversial subject. Resource allocation in health systems rarely has focused on those who need it most and, in addition, is often influenced by political interests. The study assesses the distribution of hospital beds in different regions in Tehran, Iran, during 2010–2012.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in all regions of Tehran (22 regions) during 2010 to 2012. All hospital beds in these regions are included in the study. Data regarding populations of each region were obtained from the Statistics Center of Iran. According to the data, the total number of beds (N.B) and population (P) in 2010 (N.B=19075, P= 7585000), 2011 (N.B=21632, P= 9860500), and 2012 (N.B=21808, P=12818650). The instrument was a form, including the name of the hospital, the district in which the hospital was located, the number of staffed beds, the name of each region, and its population. Data analysis was performed using DASP software version 2.3.

Results

The results demonstrate that the Gini coefficient of distributed beds in 22 regions of Tehran was 0.46 in all three years and specifically calculated 0.4666 in 2010, 0.4658 in 2011 and 0.4652 in 2012. The Gini coefficient of beds in 22 regions of Tehran is not fair in comparison with the population of each region during the years 2010 to 2012.

Conclusion

The results demonstrate that the distribution of beds in regions in Tehran is not fair in relation to the population of each region—and some regions had no hospitals. Therefore, it is essential for policymakers to frequently monitor this issue and investigate the fair distribution of hospital beds.

Keywords: hospital bed capacity, hospitals, urban, health care rationing/organization and administration, beds/supply and distribution

1. Introduction

Distribution of hospital beds across regions is a controversial subject. Resources allocation in health systems rarely have focused on those most in need and, in addition, are often influenced by political interests (1). Today, researchers and policymakers are increasingly paying attention to the distribution of health care resources such as beds, doctors, and equipment as indicators of general health (2). Although the problems related to fairness in the distribution of health care resources, and, in particular, measurement of it does not appear easy but has a strong impact on policymaking and resource allocation in the health system (3). Nowadays, fairness in distribution of health resources and elimination of inequality in the health sector have become major concerns of health systems in the world, especially in developing countries (4). Regardless of different concepts of equality, it is the base for services system, and the focus should be on fair distribution of services among different social groups (5). Adopting particular and scientific policies to increase the amount of health care resources and the way in which they are allocated and distributed is, thus, a crucial issue (6). In order to analyze the level of inequality in the distribution of health resources, statisticians and economists have suggested several methods, the most appropriate of which is calculating the Gini coefficient. This coefficient is a quantity with the value between 0 (minimum inequality) and 1 (maximum inequality), which is symmetric and independent of the mean (7). In Iran, distribution of hospital beds refers to type of beds that advantageous provinces enjoy, such as having physicians, hospital beds, laboratories, and medical radiology, and medical facilities, in some cases, may have as much as three times more than disadvantaged, deprived, and underprivileged provinces in relation to their population. The Gini coefficient has been used in various studies in Iran. Meskarpour-Amiri et al., for example, assessed trends of distribution of CCU, ICU, and NICU beds in Iran by Gini coefficient and demonstrated that the inequality trend between 2010 to 2012 in the distribution of intensive care beds in Iran had increased; the authors also predicted that unequal distribution of intensive care beds in the next five years in Iran will be extreme if the trend continues (8). Omrani-khoo et al. also assessed inequality in the distribution of hemodialysis beds in relation to hemodialysis patients, and, according to the results, inequality was not seen in hemodialysis beds in the population level (9). The two studies used the Gini coefficient in special beds in hospitals, while Mostafavi et al. used this method in university hospital beds in the Azarbaijan-gharbi Province in Iran and demonstrated inequality in the distribution of hospital beds in the province (10). The general objective of this research was to determine inequality in distribution of all hospital beds in Tehran, Iran, during 2010–2012. The specific objectives were to determine trends of inequality distribution and the difference among these three years.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Research design

The present study investigates the equality or inequality of the distribution of staffed hospital beds in different regions of Tehran Province during the years 2010 to 2012. To do so, the Ministry of Health, Treatment, and Medical Education supplied the number of staffed hospital beds in all hospitals in Tehran. Then, according to the information from Tehran Municipality, hospitals of each region were separated, and the number of staffed beds in each region was determined. To estimate the degree of indexes, the regional population of the province was used and the number of beds per population in each region was measured.

2.2. Sampling

Sampling was not done in this study. All 124 hospitals in Tehran were studied by census. Tehran is the capital of Iran and Tehran Province. With a population of around 8.4 million and 13 million in the wider metropolitan area, Tehran is Iran’s largest city and urban area, the largest city in Western Asia, and one of the largest three cities in the Middle East (along with Istanbul and Cairo). Tehran is divided into 22 municipal districts, each with its own administrative center. Each of these municipal districts is further subdivided into municipal regions. Twenty of the 22 municipal districts are located in Tehran County’s Central District, while District 1 is in Shemiranat County, and District 20 is in Rey County.

2.3. Measurement tools

The instrument for gathering data was a researcher-developed form, which contains the name of the hospital, the district in which the hospital is located, the number of staffed beds, the name of regions in Tehran, and the population number in each region.

2.4. Data collection

The completed forms were inserted in Excel in three sheets of 2010, 2011, and 2012. Then, by referring to the Ministry of Health, Treatment, and Medical Education, the information was completed by the researcher and experts in the relevant units.

2.5. Research ethics

Information collective via questionnaire was completely confidential, and the results of the research were given to the managers.

2.6. Statistical analyses

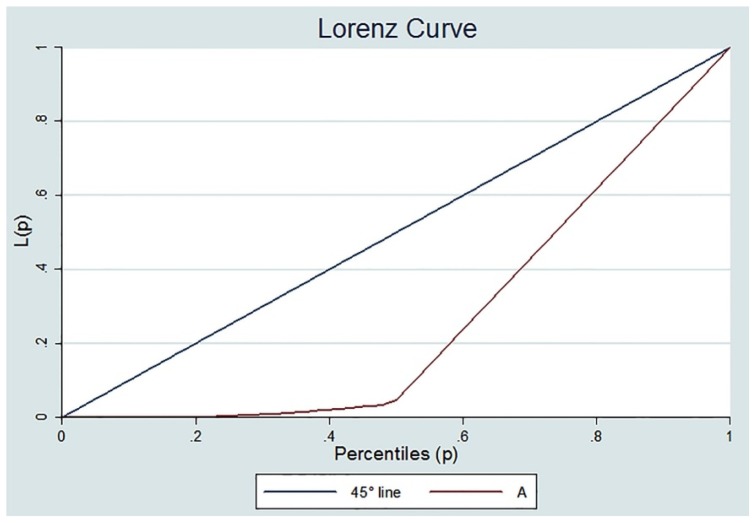

The information was entered into DASP Version 2.3, and its Gini coefficient and Lorenz curve were determined. Numerical value of the Gini index is between 0 and 1, where 0 represents perfect equality and 1 represents perfect inequality. When the Gini index is less than 0.2, complete equality is observed in the distribution. If the value of the Gini index is between 0.2–0.3, moderate equality is observed in the distribution. The values between 0.3–0.4 show inequality in the distribution, and values between 0.4–0.6 represent high inequality in the distribution. Values greater than 0.6 indicate perfect inequality (11).

3. Results

One hundred and twenty-four hospitals were actively providing services when the study was conducted in Tehran. These hospitals provided all kinds of health and treatment services, were either public or private, and managed by the government, private organizations, or individuals. The Gini coefficient of beds in 22 regions in Tehran in relation to the population in each region in 2010 was obtained to be 0.4666. The Gini coefficient of the beds in 22 regions of Tehran in relation to the population of each region in 2011 was obtained to be 0.4658. The Gini coefficient of beds in 22 regions in Tehran in relation to the population of each region in 2012 was obtained to be 0.4652 (Table 1). The Lorenz curve of distribution of hospital beds in 2010–2012 is shown in Figure 1. The Lorenz curve plotted in the three years of the study demonstrate there is a big gap between the line of equality and Lorenz curve, which indicates distribution of beds in the areas is not fair.

Table 1.

Gini Coefficient of Distribution of Beds in Relation to Population in 2010–2012

| Parameters | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Estimate | 0.4666 | 0.4658 | 0.4652 |

| STE | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Minimum (bed) | 78 | 92 | 124 |

| Maximum (bed) | 1165 | 1314 | 1379 |

| Minimum (population) | 138000 | 179400 | 233220 |

| Maximum (population) | 800000 | 1040000 | 1352000 |

| M ± SD (bed) | 164.24 | 172.02 | 179.78 |

| Mean (population) | 390227.27 | 507295.45 | 659484.09 |

Figure 1.

Lorenz curve for the distribution of beds in relation to population in 2010–2012

4. Discussion

The results further demonstrate that Gini coefficient of beds in 22 regions of Tehran in relation to the population of each region during the years 2010 to 2012 is not fair. In all three years, it was 0.46, although as we grew closer to the year 2012, the situation changed for the better. The numerical value of the Gini index between 0.4–0.6 represents a large disparity in the distribution. Based on the theoretical basis, a Gini coefficient of less than 0.2 indicates perfect equality in the distribution of resources; thus, the most important element in the definition of equality is allocation and distribution of resources according to need (12). Therefore, this study faces high inequality in the distribution of beds in different regions of Tehran.

In a study by De Bruin et al. on the distribution of CCU beds in 24 university hospitals in The Netherlands in the period from 2004 to 2006, the Gini coefficient was reported to be 0.65 and 0.5, respectively, for the mentioned years, which clearly indicates unequal distribution of beds in the studied hospitals (11). In a study to investigate geographical disparity trends in the allocation of resources in the United States, T. Horev et al. pointed to a descending trend of equality in the distribution of physicians in relation to hospital beds in a period of 30 years (13). The results of this study and other studies demonstrate that, taking into account the number of hospital beds as the basis of equality, the studied areas are facing inequality and disparity in health. Although solving problems related to equity in the distribution of health resources, particularly its measurement, does not seem easy, this issue has had a significant impact on policies and resource allocation in health systems (2). In this regard, WHO also has emphasized the necessity of equality measurement in the distribution of resources because, with regard to access to health care services as a fundamental right of all human beings, inequality in the geographical distribution of health resources creates difficulties for access to these services (14). In developing countries, these problems are more profound and salient due to weaknesses in information recording, gathering, maintaining, and analyzing systems for planning in the health sector. Therefore, the degree of geographical equality and equality in the distribution of health resources as an index of general health must be increasingly further considered (15). Given that the most important measure or criterion for computing other resources such as physicians, nurses, and equipment is hospital beds, equality in the distribution of hospital beds can implicitly bring about equality in the distribution of other service factors.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the distribution of beds in Tehran regions is not fair relative to the population, and some regions have no hospitals. It is necessary for policymakers to engage in repetitive monitoring in this regard and, based on that monitoring, investigate the distribution of hospital beds. It is also proposed that distribution of beds be considered according to specialized beds and intensive care units.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences grant number 27409. Also, the authors acknowledge the Department of Statistics of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

iThenticate screening: October 26, 2015, English editing: November 03, 2015, Quality control: December 07, 2015

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Authors' contributions: All authors contributed to this project and article equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Shinjo D, Aramaki T. Geographic distribution of healthcare resources, healthcare service provision, and patient flow in Japan: a cross sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(11):1954–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asada Y. Assessment of the health of Americans: the average health-related quality of life and its inequality across individuals and groups. Popul Health Metr. 2005;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukeri K, Alonso-Betancourt O, Emsley R. Staff and bed distribution in public sector mental health services in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;20(4):160–5. doi: 10.7196/sajp.570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashad H, Khadr Z. Measurement of health equity as a driver for impacting policies. Health Promot Int. 2014;29( Suppl 1):i68–82. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glorioso V, Subramanian SV. Equity in Access to Health Care Services in Italy. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):950–70. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mobaraki H, Hassani A, Kashkalani T, Khalilnejad R, Chimeh EE. Equality in Distribution of Human Resources: the Case of Iran’s Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Supple1):161–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Y, Zhou X. Income inequality in today’s China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(19):6928–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403158111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meskarpour-Amiri M, Mehdizadeh P, Barouni M, Dopeykar N, Ramezanian M. Assessment the trend of inequality in the distribution of intensive care beds in Iran: using GINI index. Global journal of health science. 2014;6(6):28–36. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omrani-Khoo H, Lotfi F, Safari H, Zargar Balaye Jame S, Moghri J, Shafii M. Equity in Distribution of Health Care Resources; Assessment of Need and Access, Using Three Practical Indicators. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(11):1299–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mostafavi H, Aghlmand S, Zandiyan H, Alipoori Sakha M, Bayati M, Mostafavi S. Inequitable Distribution Of Specialists And Hospital Beds In West Azerbaijan Province. Payavard Salamat. 2015;9(1):55–66. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bruin AM, Bekker R, van Zanten L, Koole GM. Dimensioning hospital wards using the Erlang loss model. Ann Oper Res. 2010;178(1):23–43. doi: 10.1007/s10479-009-0647-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ameryoun A, Meskarpour-Amiri M, Dezfuli-Nejad ML, Khoddami-Vishteh H, Tofighi S. The assessment of inequality on geographical distribution of Non-cardiac intensive care beds in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40(2):25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horev T, Pesis-Katz I, Mukamel DB. Trends in geographic disparities in allocation of health care resources in the US. Health policy. 2004;68(2):223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calman K. The ethics of allocation of scarce health care resources: a view from the centre. J Med Ethics. 1994;20(2):71–4. doi: 10.1136/jme.20.2.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asada Y. Assessment of the health of Americans: the average health-related quality of life and its inequality across individuals and groups. Population Health Metrics. 2005;3(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]