Significance

Food security and the economic well-being of millions of people depend on sustainable fisheries, which require innovative approaches to management that can balance ecological, economic, and social objectives. We offer empirical evidence that dynamic ocean management, or real-time ocean management, can increase the efficacy and efficiency of fisheries management over static approaches by better aligning human and ecological scales of use. Furthermore, we show that dynamic management can address critical ecological patterns previously considered to be largely intractable in fisheries management (e.g., competition, niche partitioning, predation, parasitism, or social aggregations) at appropriate scales. The evidence and theory offered supports the use of dynamic ocean management in a range of scenarios to improve the ecological, economic, and social sustainability of fisheries.

Keywords: dynamic ocean management, real-time management, ecosystem-based fisheries management, spatiotemporal, bycatch

Abstract

In response to the inherent dynamic nature of the oceans and continuing difficulty in managing ecosystem impacts of fisheries, interest in the concept of dynamic ocean management, or real-time management of ocean resources, has accelerated in the last several years. However, scientists have yet to quantitatively assess the efficiency of dynamic management over static management. Of particular interest is how scale influences effectiveness, both in terms of how it reflects underlying ecological processes and how this relates to potential efficiency gains. Here, we address the empirical evidence gap and further the ecological theory underpinning dynamic management. We illustrate, through the simulation of closures across a range of spatiotemporal scales, that dynamic ocean management can address previously intractable problems at scales associated with coactive and social patterns (e.g., competition, predation, niche partitioning, parasitism, and social aggregations). Furthermore, it can significantly improve the efficiency of management: as the resolution of the closures used increases (i.e., as the closures become more targeted), the percentage of target catch forgone or displaced decreases, the reduction ratio (bycatch/catch) increases, and the total time–area required to achieve the desired bycatch reduction decreases. In the scenario examined, coarser scale management measures (annual time–area closures and monthly full-fishery closures) would displace up to four to five times the target catch and require 100–200 times more square kilometer-days of closure than dynamic measures (grid-based closures and move-on rules). To achieve similar reductions in juvenile bycatch, the fishery would forgo or displace between USD 15–52 million in landings using a static approach over a dynamic management approach.

Although traditional fisheries management has focused on assessing the health of individual fish stocks, there has been a strong trend over the past two decades toward the incorporation of ecosystem components into fisheries management (1, 2). Ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) seeks to meet multiple, potentially conflicting goals across ecological, economic, and social objectives (3, 4). Meeting these goals is made more complex in marine ecosystems due to the inherent dynamic nature of the oceans. In response to continuing difficulty in managing the ecosystem impacts of fisheries in a highly dynamic environment, including bycatch (i.e., the accidental interaction of fishing gear with nontarget species), interest in the concept of dynamic ocean management (DOM) has accelerated (5–10). Maxwell et al. (8) define dynamic management as “management that changes in space and time in response to the shifting nature of the ocean and its users based on the integration of new biological, oceanographic, social and/or economic data in near real-time” (8). Dynamic management reflects advancement in our ability to manage ocean resources across finer spatial and temporal scales as a result of technological improvements that have paved the way for higher-resolution collection of both fisheries and environmental data (e.g., electronic logbooks, vessel monitoring systems, smartphone technology, remote sensing, and animal tracking) (9). The existing literature has focused on the presumed capacity of dynamic management to increase management efficiency across both ecological and economic objectives (7, 8), and in codifying the different approaches to dynamic management across fisheries and other applications (7, 10). However, little to no empirical research exists to quantify the implied benefits of dynamic management or compare the efficiency of the various spatiotemporal management measures. Additionally, and critically, the benefits of dynamic management hinge on the premise that it is capable of managing resources at scales more aligned with resources and resource users, yet we lack a quantitative assessment of how scale influences the effectiveness of dynamic management—both in terms of how it reflects underlying ecological processes, and how this relates to the efficiency of dynamic management approaches.

Scale in Fisheries Management

Frameworks for dynamic management (e.g., ref. 6) have defined it in contrast to traditional static spatiotemporal management of fisheries (i.e., coordination of fisheries in space and/or time) including monthly or seasonal closures of specific areas (often known as “time–area closures”), and seasonal full-fishery closures. Alternatively, dynamic management operates at smaller scales of space and time, and depends on contemporaneous conditions. Work on dynamic management has focused on three types of measures: grid-based hot-spot closures, real-time closures based on move-on rules, and oceanographic closures. Grid-based closures involve the overlaying of a grid on an area of interest and closing individual grid cells where bycatch has exceeded a threshold level (e.g., refs. 11 and 12); they have been implemented on a daily or weekly basis with cell sizes as small as ∼50 km2. Move-on rules are similarly triggered by a threshold, but rather than using predefined grid cells, fishermen must move a set distance away from the affected area. Move-on rules have been widely implemented with real-time closures lasting days to weeks over distances as short as 2–10 km in radius (5, 10, 13, 14), with the potential to be implemented on temporal scales of days or hours if higher-resolution catch data are incorporated. Oceanographic closures are areas defined by environmental conditions (e.g., sea surface temperature) and have been implemented on a daily (15) and biweekly (16, 17) basis. In the only compulsory example, the Eastern Australia pelagic longline fishery employs a habitat model to inform a dynamic oceanographic closure to reduce bycatch of southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) based on 5-km resolution temperature data, but the oceanographic closure is implemented at a much coarser scale (17).

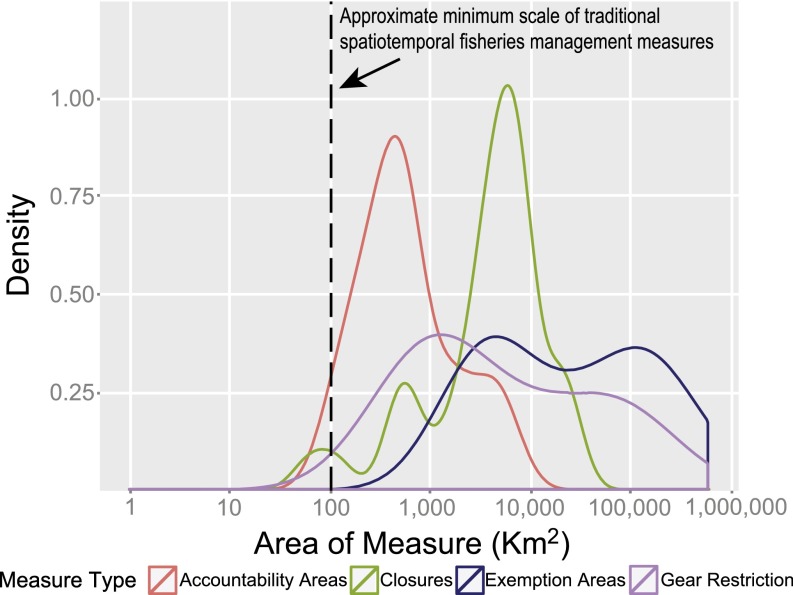

Although there are active examples of dynamic management, the vast majority of spatiotemporal fisheries management measures are static and occur at much larger scales. The resolution and extent of fisheries management have largely been dictated by logistical, and legal and political constraints, respectively, and secondarily by the geographic range of the species or subpopulation dynamics (18). Management units in developed coastal fisheries are rarely smaller than 1,000 km2, and management measures are generally larger than 100 km2. For example, in the Northeast Multispecies Fishery in the United States from which the data for this study are drawn (see Methods for further details on the fishery), the mean size of a spatiotemporal management measure is 25,635 km2 (n = 74; range, 61–592,539 km2; SD, 78,339 km2; Fig. 1 and Table S1). If we consider only closures, the mean is 6,344 km2 (n = 33; range, 61–23,454 km2; SD, 6,194 km2; Table S1). From a temporal perspective, the resolution of management measures is at best a month (e.g., Rolling Closure Areas) and generally a year (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Density of the area of spatiotemporal management measures in the Northeast Multispecies Fishery. Data abstracted from the Greater Atlantic Region Fisheries Office (www.greateratlantic.fisheries.noaa.gov/educational_resources/gis/data/index.html; downloaded on March 30, 2015). Only one management measure in the fishery, Fippennies Ledge Area, is finer than 100 km2 (Table S1).

Table S1.

Full list of spatiotemporal management measures in the Northeast Multispecies Fishery

| ID | Type | Area name | Time, d | Area, km2 | Implementing regulation | Code of Federal Regulations |

| 1 | Closures | Sector Rolling Closure Area II | 29 | 7,308 | Amendment 16 | 648.81(f)(2)(vi)(A) |

| 2 | Closures | Sector Rolling Closure Area III | 29 | 8,364 | Amendment 16 | 648.81(f)(2)(vi)(B) |

| 3 | Closures | Sector Rolling Closure Area IV | 29 | 7,054 | Amendment 16 | 648.81(f)(2)(vi)(C) |

| 4 | Closures | Western GOM Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 2,274 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(i) |

| 5 | Closures | Cashes Ledge Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 444 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(ii) |

| 6 | Closures | Jeffrey's Bank Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 499 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(iii) |

| 7 | Closures | Closed Area I–North Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 1,937 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(iv) |

| 8 | Closures | Closed Area II Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 639 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(v) |

| 9 | Closures | Closed Area I–South Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 589 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(iv) |

| 10 | Closures | Nantucket Lightship Habitat Closure Area | 365 | 3,389 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(h)(1)(vi) |

| 11 | Closures | Georges Bank Seasonal Closure Area | 29 | 21,897 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(g)(1) |

| 12 | Closures | Rolling Closure Area I | 30 | 6,875 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(f)(1)(i) |

| 13 | Closures | Rolling Closure Area II | 29 | 21,004 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(f)(1)(ii) |

| 14 | Closures | Rolling Closure Area III | 30 | 23,454 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(f)(1)(iii) |

| 15 | Closures | Rolling Closure Area IV | 29 | 17,591 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(f)(1)(iv) |

| 16 | Closures | Rolling Closure Area V | 60 | 3,757 | Amendment 13 | 648.81(f)(1)(v) |

| 17 | Closures | GOM Cod Spawning Protection Area | 90 | 114 | Framework 45 | 648.81(n)(1) |

| 18 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 1 | 30 | 4,941 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(i) |

| 19 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 2 | 27 | 4,941 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(ii) |

| 20 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 3 | 30 | 9,224 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(xi) |

| 21 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 4 | 29 | 8,473 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(xii) |

| 22 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 5 | 29 | 8,776 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(v) |

| 23 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 6 | 29 | 5,137 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(vi) |

| 24 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 7 | 60 | 5,673 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(vii) |

| 25 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 8 | 60 | 3,417 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(xiii) |

| 26 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 9 | 29 | 6,218 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(xiv) |

| 27 | Closures | Seasonal Interim Closure Area 10 | 30 | 3,757 | GOM Cod Interim Rule | 648.81(o)(1)(xv) |

| 28 | Closures | Fippennies Ledge Area | 365 | 61 | Framework 48 | 648.87(c)(2)(i)(A) |

| 29 | Closures | Closed Area I | 365 | 3,955 | Framework 9 | 648.81(a)(1) |

| 30 | Closures | Closed Area II | 365 | 6,906 | Framework 9 | 648.81(b)(1) |

| 31 | Closures | Nantucket Lightship Closed Area | 365 | 6,268 | Framework 9 | 648.81(c)(1) |

| 32 | Closures | Cashes Ledge Closure Area | 365 | 1,377 | Framework 25 | 648.81(d)(1) |

| 33 | Closures | Western GOM Closure Area | 365 | 3,032 | Framework 25 | 648.81(e)(1) |

| 34 | Special access programs | CA I Hook Gear Haddock SAP Area | 275 | 2,619 | Amendment 16 | 648.85(b)(7)(ii) |

| 35 | Special access programs | Closed Area II Yellowtail Flounder/Haddock SAP Area | 214 | 3,868 | Amendment 13 | 648.85(b)(3)(ii) |

| 36 | Special access programs | Eastern US/Canada Haddock SAP Area | 152 | 3,756 | Framework 40-A | 648.85(b)(8)(ii) |

| 37 | Gear restriction areas | GOM/GB Inshore Restricted Roller Gear Area | 365 | 11,388 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(a)(3)(vii) |

| 38 | Gear restriction areas | GOM Regulated Mesh Area | 365 | 57,437 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(a)(1) |

| 39 | Gear restriction areas | GB Regulated Mesh Area | 365 | 112,181 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(a)(2) |

| 40 | Gear restriction areas | Restricted Gear Area I | 258 | 592 | Amendment 16 | 648.81(j)(1) |

| 41 | Gear restriction areas | Restricted Gear Area II | 201 | 720 | Framework 22 | 648.81(k)(1) |

| 42 | Gear restriction areas | Restricted Gear Area III | 163 | 2,277 | Framework 22 | 648.81(l)(1) |

| 43 | Gear restriction areas | Restricted Gear Area IV | 106 | 1,304 | Framework 22 | 648.81(m)(1) |

| 44 | Accountability areas | Northern Windowpane Flounder and Ocean Pout Large AM Area | 365 | 4,641 | Framework 47 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(1) |

| 45 | Accountability areas | Southern Windowpane Flounder and Ocean Pout Large AM Area 1 | 365 | 1,806 | Framework 47 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(1) |

| 46 | Accountability areas | Southern Windowpane Flounder and Ocean Pout Large AM Area 2 | 365 | 569 | Framework 47 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(1) |

| 47 | Accountability areas | Northern Windowpane Flounder and Ocean Pout Small AM Area | 365 | 1,558 | Framework 47 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(1) |

| 48 | Accountability areas | Southern Windowpane Flounder and Ocean Pout Small AM Area | 365 | 519 | Framework 47 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(1) |

| 49 | Accountability areas | Atlantic Halibut Trawl Gear AM Area | 365 | 4,619 | Framework 48 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(2) |

| 50 | Accountability areas | Atlantic Halibut Fixed Gear AM Area 1 | 365 | 127 | Framework 48 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(2) |

| 51 | Accountability areas | Atlantic Halibut Fixed Gear AM Area 2 | 365 | 251 | Framework 48 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(2) |

| 52 | Accountability areas | Atlantic Wolffish Trawl Gear AM Area | 365 | 572 | Framework 48 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(3) |

| 53 | Accountability areas | Atlantic Wolffish Fixed Gear AM Area 1 | 365 | 257 | Framework 48 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(3) |

| 54 | Accountability areas | Atlantic Wolffish Fixed Gear AM Area 2 | 365 | 127 | Framework 48 | 648.90(a)(5)(i)(D)(3) |

| 55 | Accountability areas | SNE/MA Winter Flounder Trawl Gear AM Area 1 | 365 | 508 | Framework 50 | 648.82(n)(2)(vii) |

| 56 | Accountability areas | SNE/MA Winter Flounder Trawl Gear AM Area 2 | 365 | 518 | Framework 50 | 648.82(n)(2)(vii) |

| 57 | Accountability areas | SNE/MA Winter Flounder Trawl Gear AM Area 3 | 365 | 259 | Framework 50 | 648.82(n)(2)(vii) |

| 58 | Accountability areas | SNE/MA Winter Flounder Trawl Gear AM Area 4 | 365 | 454 | Framework 50 | 648.82(n)(2)(vii) |

| 59 | Exemption areas | GOM/GB Exemption Area | 365 | 106,329 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(a)(17) |

| 60 | Exemption areas | MA Exemption Area | 365 | 592,539 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(c)(5) |

| 61 | Exemption areas | GOM Scallop Dredge Exemption Area | 365 | 38,002 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(a)(11) |

| 62 | Exemption areas | Great South Channel Scallop Dredge Exemption Area | 365 | 6,168 | Standalone final rule | 648.80(a)(18) |

| 63 | Exemption areas | GOM/GB Dogfish and Monkfish Gillnet Fishery Exemption Area | 75 | 20,561 | Framework 20 | 648.80(a)(13) |

| 64 | Exemption areas | Nantucket Shoals Mussel and Sea Urchin Dredge Exemption Area | 365 | 5,610 | Amendment 7 | 648.80(a)(12) |

| 65 | Exemption areas | Nantucket Shoals Dogfish Fishery Exemption Area | 136 | 5,610 | Amendment 7 | 648.80(a)(10) |

| 66 | Exemption areas | Eastern Cape Cod Spiny Dogfish Exemption Area | 213 | 1,987 | Standalone Final Interim Rule | 648.80(a)(19)(i) |

| 67 | Exemption areas | Western Cape Cod Spiny Dogfish Exemption Area | 91 | 2,373 | Standalone Final Interim Rule | 648.80(a)(19)(ii) |

| 68 | Exemption areas | SNE Exemption Area | 365 | 220,275 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(b)(10) |

| 69 | Exemption areas | SNE Dogfish Gillnet Exemption Area | 183 | 132,313 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(b)(7) |

| 70 | Exemption areas | SNE Little Tunny Gillnet Exemption Area | 60 | 2,089 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(b)(9) |

| 71 | Exemption areas | SNE Monkfish and Skate Gillnet Exemption Area | 365 | 132,313 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(b)(6) |

| 72 | Exemption areas | SNE Monkfish and Skate Trawl Exemption Area | 365 | 169,833 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(b)(5) |

| 73 | Exemption areas | SNE Scallop Dredge Exemption Area | 365 | 34,375 | Amendment 13 | 648.80(b)(11)(i) |

| 74 | Exemption areas | SNE Skate Bait Trawl Exemption Area | 122 | 4,357 | Standalone Final Interim Rule | 648.80(b)(12)(i) |

Modified from data available at the Greater Atlantic Region Fisheries Office (www.greateratlantic.fisheries.noaa.gov/educational_resources/gis/data/index.html; downloaded on March 30, 2015).

Implication of Scale-Dependent Drivers of Ecosystem Structure for Fisheries Management

To understand the need to manage at sub–100-km2 and 1-mo scales (i.e., the need to use dynamic management) and the efficiency gains potentially afforded by doing so, we need to understand how those scales interact with ecosystem structure and fisheries management. The processes responsible for producing pattern in marine ecological systems vary widely across spatial and temporal scales. At the base of marine ecosystems, the drivers of variability in biomass are scale dependent (19, 20). Plankton abundance is generally a function of highly variable forcing factors influencing growth (light, temperature, and nutrient availability) and distribution at fine scale (e.g., molecular processes, internal waves and tides, and biophysical interactions), mesoscale (e.g., surface tides, fronts, and eddies), and macroscale [e.g., basinal variability, decadal/multidecadal oscillations, and climate change (21–24); reviewed in refs. 25–27]. These patterns are also true for higher trophic level organisms (including fishermen), which are also patchy and forced by diverse scale-dependent drivers, although temporal and spatial lags often exist for higher trophic level organisms because they are not as tightly coupled with physical processes and the distribution of primary productivity (18, 28, 29).

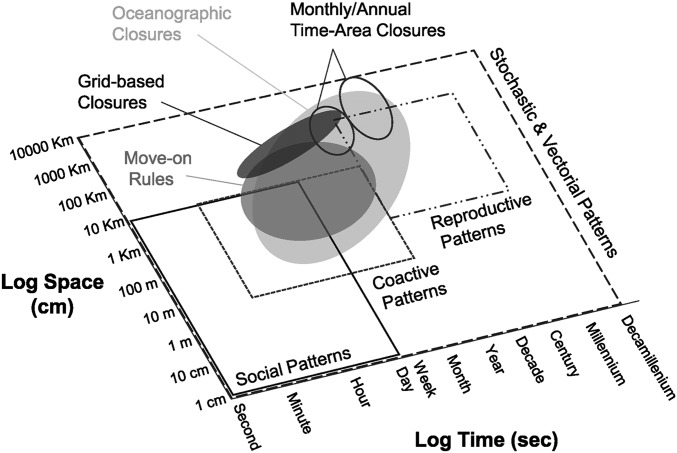

Drivers of ecosystem structure at scales smaller than 100 km2, however, differ from larger scales by including coactive and social patterns as dominant forces, as opposed to vectorial (i.e., environmental) and reproductive patterns (Fig. 2) (19). Coactive patterns, as defined by Hutchinson (30), arise from interactions between species (e.g., competition, niche partitioning, predation, and parasitism), whereas social patterns are “determined by signalling of various kinds, leading either to spacing or aggregation” (e.g., facilitated foraging, local enhancement, predator avoidance, territoriality). Coactive patterns have been widely described in the marine realm (31–34), and similarly, social patterns are seen within taxa (35, 36), and among them (37, 38). As fishing itself is a predator–prey interaction with strong social pressures among fishermen, patterns of fishing effort within a fishery are also forced by social and coactive processes at sub–100-km2 scales (39–41). If variability in the distribution and abundance of target species and fishing effort are based on multiple drivers across multiple scales, we can assume that effective fisheries management should also be a multiscale process, capable of addressing drivers at all tractable scales. However, as seen in the example of the size distribution of Northeast Multispecies Fishery measures (Fig. 1), this is rarely the case. Fisheries management is almost entirely a mesoscale activity. As such, attempts to manage processes and patterns at sub–100-km2, sub–1-mo resolution likely involves some level of spatiotemporal mismatch and some degree of inefficiency.

Fig. 2.

Spatiotemporal scales of Hutchinson’s five patterns and fishery management measures. Traditional spatiotemporal fisheries management measures (i.e., monthly and annual time–area closures) can only address reproductive and some vectorial patterns at appropriate scales. However, dynamic management measures (i.e., closures based on oceanography, grid-based hotspot closures, and real-time closures based on move-on rules) should be able to address social and coactive patterns as well as some vectorial and reproductive patterns.

Evaluation of Static vs. Dynamic Management Measures

Studies comparing static and dynamic measures are lacking despite the potential to increase efficiency through the use of dynamic measures to align the scales of resource variability, resource use, and resource management (7, 8). In a precursor to the recent work on dynamic management, Grantham et al. (42) looked at the efficiency of closures to reduce bycatch by examining permanent full-fishery closures, seasonal full-fishery closures, and a series of temporary (monthly) time–area closures. Although this effort represented a major step forward in considering the utility of dynamic management measures, it did not incorporate many of the aspects of what it might mean for a closure to be “dynamic” (e.g., near real-time closures based on contemporaneous conditions). A study comparing dynamic and static measures by O’Keefe et al. (43) evaluates the effectiveness of time/area closures, quotas/caps, and fleet communication to reduce fisheries bycatch against a set of five criteria. Evaluation criteria include “(1) reduced identified bycatch or discards, (2) no or minimal negative effect on the catch of target species, (3) no or minimal negative effect on the catch of other nontarget species or sizes, (4) no or minimal spatial or temporal displacement of bycatch, and (5) economically viable for the fisher.” Their results indicated that four of the five static time–area closures studied failed to meet even two of the criteria, whereas all of the more dynamic measures used were able to meet at least three criteria (mean, ∼4.125 of the criteria). However, no statistical tests were run to show significant differences between the two types of measures. Clearly, broader, quantitative evaluations of dynamic management are necessary, particularly using scenarios capable of comparing across multiple types of static and dynamic management to understand how efficiency differs between them, and within dynamic management approaches themselves.

Here, we highlight the importance of scale for dynamic management and the potential efficacy of dynamic management across both ecological objectives (through reduction of bycatch) and economic objectives (through decreased target catch affected and time–area closed) in the US Northeast Multispecies Fishery. Specifically, we use simulation modeling to compare the ability of closures across a range of spatial and temporal scales to meet a common management goal: the reduction of regulatory discards of undersized (juvenile) target species (Atlantic cod; Gadus morhua) while minimizing affected marketable catch and the time–area closed. We compare the efficacy and efficiency of dynamic measures (grid-based “hot-spot” measures and move-on rules) to optimized static monthly and annual closures developed through the use of a spatial conservation prioritization tool (i.e., Marxan) (44, 45). In doing so, we attempt to address both the empirical evidence gap for the increased efficiency of dynamic management over static management, as well as attempt to further the ecological theory underpinning dynamic management.

Results

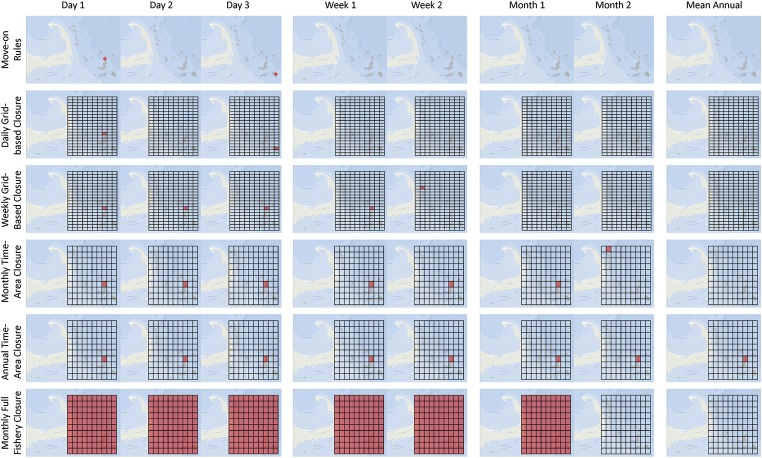

Using fishery observer data, we simulated six types of closures: (i) seasonal full-fishery closures; (ii) static annual time–area closures; (iii) monthly time–area closures; (iv and v) daily and weekly grid-based hot-spot closures; and (vi) real-time closures based on move-on rules (Fig. S1). Oceanographic closures were not considered due to limitations in the resolution and accuracy of currently available models of bottom temperature for the study area. To compare the six types of closures, we examined (i) the percent bycatch reduction achieved by weight; (ii) the percent target catch affected by weight (i.e., target catch forgone or displaced); (iii) the bycatch reduction efficiency; and (iv) the percentage of the time and area closed to fishing required to achieve the bycatch reduction (i.e., the spatiotemporal efficiency of the closure); see Supporting Information for details on how individual metrics were calculated for each closure type. We also developed a summary metric, the spatiotemporal utility metric (SUM), to integrate the other metrics and convey the overall utility of the measures.

Fig. S1.

Examples of the six types of closures simulated in this study over daily, weekly, monthly, and annual scales. Red cells indicate cells that were closed for more than 50% of the time period (e.g., more than 3 d for a weekly time period, or more than 2 wk for a monthly time period). Although the monthly and annual closures in this study were simulated using Marxan to optimize bycatch reduction across a grid, such time–area closures are more frequently implemented in real-world scenarios based on expert opinion and in negotiation with stakeholders.

The time–area required for an individual closure can be considered the resolution of the management measure. For instance, each closure based on move-on rules had an area of ∼20 km2 and was closed for 1 d, resulting in a 20 km2⋅d/closure resolution. Seen this way, the measures can be ordered by resolution: high-resolution (move-on rules, 20 km2⋅d per closure; grid-based closures, 50 km2⋅d per closure), medium-resolution (weekly grid-based closures, 350 km2⋅d per closure; monthly time–area closures, 3,000 km2⋅d per closure), and low-resolution closures (annual time–area closures, 36,500 km2⋅d per closure; and monthly total closures, 78,000 km2⋅d per closure). Results of the closure simulations are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3 ordered from high to low resolution of the individual closure.

Table 1.

Results from the simulation of six different closures type spanning a range of spatial and temporal scales

| Closure type | BLM or weight threshold, lb | Percent bycatch reduction | Percent target catch affected | Bycatch reduction efficiency | No. of closures | Area of closure; resolution, km2 | Days closed | Log km2⋅d of closure | Spatiotemporal efficiency, /1,000 | SUM |

| Move-on rules | NA | 62.17 | 8.57 | 7.25 | 48 | 19.63 | 1 | 2.97 | 0.2 | 4.64 |

| Daily grid-based closures | 10 | 61.66 | 17.39 | 3.55 | 30 | 50 | 1 | 3.18 | 0.3 | 4.13 |

| Weekly grid-based closures | 10 | 61.66 | 18.27 | 3.37 | 30 | 50 | 7 | 4.02 | 1.8 | 3.26 |

| Monthly time–area closures | 0.0001 | 60.01 | 18.77 | 3.20 | 5 | 100 | 30 | 4.18 | 2.6 | 3.08 |

| Annual time–area closures | 0.001 | 68.72 | 37.47 | 1.83 | 2 | 100 | 365 | 4.86 | 12.8 | 2.16 |

| Monthly total closures | NA | 68.54 | 43.28 | 1.58 | 4 | 2,600 | 30 | 5.49 | 54.8 | 1.46 |

BLM, boundary length modifier (see Supporting Information); SUM, spatiotemporal utility metric that provides a summary across all metrics.

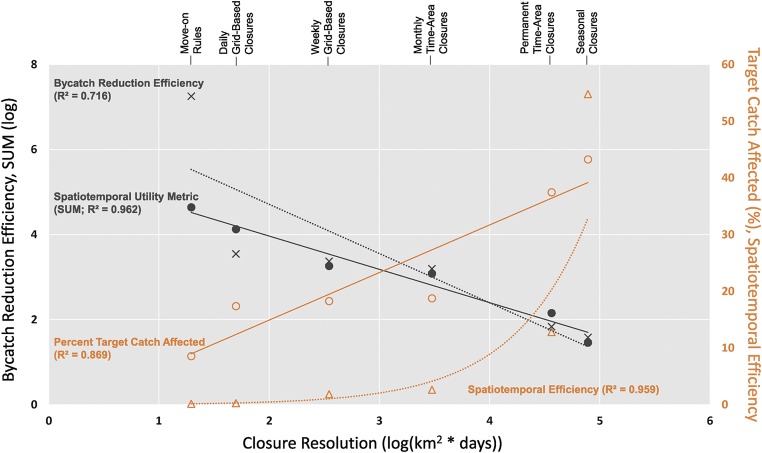

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the efficacy and efficiency of the simulated static and dynamic closure. As closure resolution decreases (i.e., as individual closures get bigger), percent catch affected and the log of the time–area required to meet the bycatch reduction target increase monotonically. Consequently, and conversely, the bycatch reduction ratio and the log of the SUM decline linearly.

A previous study showed real-time closures based on move-on rules could theoretically reduce juvenile cod bycatch 62.17% by weight (5). To draw comparisons between the real-time closures and less dynamic monthly and annual time–area closures, a general target of 60% reduction in bycatch biomass was set for all closures. Trends in the best results from each closure type based on achieving this bycatch reduction target were monotonic (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Percent target catch affected increased linearly as the resolution of the management measure decreased (slope = 8.40; R2 = 0.869). Consequently, the bycatch reduction efficiency (generally inversely related to the percent catch affected) decreased linearly with resolution (slope = −1.16; R2 = 0.716). The total kilometer-days used to achieve the target displayed a log-linear increase as resolution decreased (R2 = 0.923). The mean SUM of dynamic measures (i.e., move-on rules, daily grid-based closures, and weekly grid-based closures) was significantly higher than static measures (independent two-group Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.05).

Discussion

The results of this simulation study clearly depict how the use of more dynamic measures should reduce the negative costs associated with spatiotemporal fisheries management (i.e., lost catch or increased operational costs when effort is displaced). As the spatial and temporal resolution of the closures used increases (i.e., as more targeted closures are used), (i) the percentage of target catch affected decreases, (ii) the reduction ratio (bycatch/catch) increases, (iii) the total time–area required to achieve the target bycatch reduction decreases, and (iv) the overall SUM increases.

The coarser scale management measures (annual time–area closures and monthly full-fishery closures) affected up to four to five times the target catch and required 100–200 times the time–area of the dynamic measures (grid-based closures and move-on rules). A simple extrapolation using the value of cod landings in New England for the time period of this study ($1.524/lb*), suggests that the hypothetical difference in potential value of landings affected across the whole fishery (via displaced or forgone target catch) of using the most static measure vs. the most dynamic measure to reduce juvenile cod catch by 60% would be over US$52,750,000, or approximately a third of the value of the all of the cod landed.* The difference between real-time move-on rules and commonly used monthly time–area closures would be more than US$15,500,000. Considered as a group, dynamic measures were significantly more efficient than static measures. Higher-resolution measures had a higher SUM than lower-resolution measures across almost all scenarios [i.e., across changes in boundary length modifier (BLM) and threshold weights; Table 1 and Table S2]. However, no attempt to test for significant differences between individual measures was performed due to the small sample sizes. Allowing the BLM to vary in the Marxan runs predictably led to lower “cost” (i.e., the percent target catch affected) but also decreased the spatiotemporal efficiency of the closures.

Table S2.

Full results of all simulation model runs

| Closure type | BLM or weight threshold, lb | Percent bycatch reduction, % | Percent catch affected, % | Bycatch reduction efficiency | No. of closures | Area of closure | Days closed | Log km-days of closure | Spatiotemporal efficiency, /1,000 | SUM |

| Move-on rules | Weight = 0 | 62.17 | 8.57 | 7.25 | 48 | 19.63 | 1 | 942.24 | 0.17 | 4.642 |

| Daily grid-based closure | Weight = 0 | 71.44 | 30.88 | 2.31 | 87 | 50 | 1 | 4,350 | 0.76 | 3.481 |

| Daily grid-based closure | Weight = 1 | 71.27 | 30.41 | 2.34 | 84 | 50 | 1 | 4,200 | 0.74 | 3.502 |

| Daily grid-based closure | Weight = 5 | 67.65 | 23.65 | 2.86 | 51 | 50 | 1 | 2,550 | 0.45 | 3.805 |

| Daily grid-based closure | Weight = 10 | 61.66 | 17.39 | 3.55 | 30 | 50 | 1 | 1,500 | 0.26 | 4.129 |

| Daily grid-based closure | Weight = 25 | 52.65 | 8.91 | 5.91 | 9 | 50 | 1 | 450 | 0.08 | NA |

| Daily grid-based closure | Weight = 50 | 29.28 | 3.24 | 9.04 | 6 | 50 | 1 | 300 | 0.05 | NA |

| Weekly grid-based closure | Weight = 0 | 71.81 | 34.40 | 2.09 | 84 | 50 | 7 | 29,400 | 5.16 | 2.607 |

| Weekly grid-based closure | Weight = 1 | 71.64 | 33.92 | 2.11 | 82 | 50 | 7 | 28,700 | 5.04 | 2.622 |

| Weekly grid-based closure | Weight = 5 | 67.89 | 25.30 | 2.68 | 48 | 50 | 7 | 16,800 | 2.95 | 2.959 |

| Weekly grid-based closure | Weight = 10 | 61.66 | 18.27 | 3.37 | 30 | 50 | 7 | 10,500 | 1.84 | 3.262 |

| Weekly grid-based closure | Weight = 25 | 52.65 | 8.91 | 5.91 | 9 | 50 | 7 | 3,150 | 0.55 | NA |

| Weekly grid-based closure | Weight = 50 | 29.28 | 3.24 | 9.04 | 6 | 50 | 7 | 2,100 | 0.37 | NA |

| Monthly time–area closure | BLM = 0.00001 | 60.22 | 16.86 | 3.57 | 7 | 100 | 30 | 21,000 | 3.69 | 2.986 |

| Monthly time–area closure | BLM ≥ 0.0001 | 60.01 | 18.77 | 3.20 | 5 | 100 | 30 | 15,000 | 2.63 | 3.084 |

| Annual time–area closure | BLM = 0.00001 | 60.63 | 30.81 | 1.97 | 8 | 100 | 365 | 292,000 | 51.28 | 1.584 |

| Annual time–area closure | BLM = 0.0001 | 60.27 | 37.47 | 1.61 | 2 | 100 | 365 | 73,000 | 12.82 | 2.099 |

| Annual time–area closure | BLM ≥ 0.001 | 68.72 | 37.47 | 1.83 | 2 | 100 | 365 | 73,000 | 12.82 | 2.155 |

Simulations in bold had the highest SUM for each closure type and were used to identify trends across closure resolutions (Fig. 3).

The various metrics used suggest that the results of this study are not artifacts of the way the SUM is formulated. The spatiotemporal efficiency component likely has an outsized effect on the SUM because the range of spatiotemporal efficiency values across all closure types (spanning three orders of magnitude) is greater than the range in the bycatch reduction efficiency (less than one order of magnitude). Despite this, the three independent metrics that make up the SUM (target catch affected, bycatch reduction efficiency, and the log of spatiotemporal efficiency) all displayed the same strong trends (R2 > 0.7) with little overlap in the SUM as measures became more dynamic. Thus, although further consideration should be given to ensuring the formulation of the SUM is weighted appropriately for the context it is applied in, the general results of this study are not sensitive to changes in how the SUM is formulated.

Furthermore, the methods used to identify optimal closures for the coarser-scale spatiotemporal closures (monthly and annual time–area closures and monthly full-fishery closures) are a best-case scenario based on perfect knowledge of where the juvenile bycatch hot spots were located. That is, they were chosen after fishing occurred and the bycatch was known. The grid-based closures and real-time move-on rules are based on a trigger (i.e., bycatch in a given set exceeding a threshold) that affected sets in the future with no knowledge of where or when the future bycatch events occurred. This assumption of perfect hindsight strongly biases the results of the study in favor of the more static measures, making our conclusions regarding the utility of dynamic measures conservative.

It is important to note that DOM is made possible by the speed at which information is transferred or by defining management measures against conditions on the ground that fishermen may respond to directly. Based on technology and processes that are already in place in a number of fisheries (46), this study assumes immediate transfer of knowledge to all other fishermen in the sector. For example, mobile apps like eCatch (https://www.ecatch.org/), Digital Deck (pointnineseven.com/resources/display/digital_deck), and Deckhand (deckhandapp.com) are used by fishermen to transfer catch data in real time and can or could transmit DOM products back to fishermen. Although these tools allow for operational implementation of DOM, there is a larger question of how DOM fits within current fisheries management regimes. Previous studies have shown that DOM does not seek to supplant existing adaptive management processes but falls within the implementation component of that framework (7, 8). For example, move-on rules as they are currently implemented in numerous fisheries do not occur at a predetermined time or location and do not require management council review for each application of the measure (5, 10); rather, the distance which fishermen must move following a bycatch event is determined during the council review process and the move-on rule is applied in near real time on the ground. The potential legal constraints on the various stages encountered in implementing DOM have also been enumerated including appropriate legal notice of changes in closure location (e.g., for grid-based closures and oceanographic closures), and addressing permits that confer absolute property rights (9). In these cases, dynamic closures may violate such property rights by restricting access, although exceptions to absolute property rights already exist in a fisheries context (e.g., emergency closures due to maximum take of protected species). Moreover, this study indicates that dynamic management has less impact on fishermen (i.e., it affects less target catch and time–area) than static management. Thus, it may not be necessary to develop DOM regulations, but rather offer information to fishermen to use voluntarily to meet already legally established management goals (e.g., bycatch reduction) or improve their economic efficiency (e.g., by avoiding the need to lease more quota). In such scenarios (e.g., as implemented in the US East Coast Scallop Fishery) (12), DOM amounts to information sharing and is only limited by the aforementioned speed of content delivery.

Implications for Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management.

This study highlights the increases in efficiency that can be obtained by using finer-scale management measures than traditionally used in fisheries management, which generally occurs at mesoscale spatial resolutions and monthly or annual timescales. That is not to say that the understanding and integration of mesoscale, macroscale, and megascale processes and patterns into fisheries management is not critical. Mesoscale and macroscale are, have been, and will continue to be the dominant scales of strategic fisheries management. However, managers must develop finer-scale (1–10 km) management measures to ensure that the tactical implementation of those strategies is done as efficiently as possible.

The gap in fisheries management at scales less than 10 km also raises some doubt as to whether, and at what cost due to the inefficiency of the measures, we can meet commitments to implement ecosystem-based fisheries management with spatiotemporal measures that may be fundamentally mismatched in space and time to address important drivers of ecosystem structure (i.e., coactive and social patterns). Since its inception, calls for EBFM have contained requirements to protect ecosystem structure, stock structure, and trophic interactions (3, 47, 48). More generally, key elements of ecosystem-based management include the use of “appropriate spatial and temporal scales” and “accounting for the dynamic nature of ecosystems” (44, 49). It is critical that managers recognize ecological processes exist below 10 km and that the marine realm is a complex adaptive system where large-scale dynamics can be driven by fine-scale interactions (45, 50).

Does Dynamic Management Only Benefit Highly Mobile Species?

Beyond the question of scale, there are a number of other important ecological factors to consider as we move forward with DOM. Two recent articles (7, 8) make the argument that, as the vagility of an organism or process increases, the amount of space required to encapsulate it within a management scheme is inversely proportional to the temporal resolution used. This implies that dynamic management may be more useful for the management of highly mobile pelagic species or processes (e.g., sea turtles and tuna, or fronts and eddies), and limits the consideration of dynamic management of less mobile species. However, the work in this study shows that dynamic management can more efficiently meet management targets in demersal species as well. Considered together with other recent work (5, 10, 12, 51), a trend begins to appear indicating that the utility of dynamic management to more sedentary, demersal fisheries may be the norm, not an anomaly. Further work needs to be done to examine how dynamic management fares against a continuum of species life-histories (benthic vs. pelagic, central place foragers vs. wanderers, migratory vs. local populations, etc.). It is critical that we develop a better idea of whether, and to what degree, the use of dynamic management will reduce bycatch, decrease the time and area required to address management problems, and decrease the economic burden placed on fishermen by inefficient static management. This can be done only through the production of more example analyses examining the efficiency of spatiotemporal management measures under various scenarios.

Methods

The potential efficiency and efficacy of various static and dynamic closures were examined using observer data produced by the Northeast Fisheries Observer Program related to the Northeast Multispecies Fishery. The Northeast Multispecies Fishery management plan contains 16 species, including the iconic Atlantic cod. The Atlantic cod population has continued to decrease despite repeated attempts over decades by management to address overfishing and habitat concerns. One consistent issue across many fisheries including the Northeast Multispecies Fishery is the catch and discarding of target species smaller than the minimum size length allowed under the fishery management plan. The discarding of such juveniles or “small” fish has led to numerous regulations including gear modifications and time–area closures (5, 52). In this study, we model how time–area closures across a range of spatial and temporal scales could hypothetically decrease juvenile discards of cod in the Northeast Multispecies Fishery using high-resolution fishery-dependent data from a sector within the fishery.

Details of the method used to develop and optimize the simulated closures are provided in Supporting Information. We consider four metrics to compare static and dynamic closures (acronyms given in parentheses relate to the algorithm for calculating the SUM provided below): bycatch reduction (BR), target catch affected (TCA), bycatch reduction efficiency (BR/TCA), and spatiotemporal efficiency (STE). Bycatch reduction is the percentage (by weight) of the bycatch species that might have been avoided by using the given closure. Similarly, target catch affected is the percentage of the target catch that would be forgone or displaced if the given closure had been implemented. Bycatch reduction efficiency is the ratio of percent bycatch reduced to the percent target catch affected. Spatiotemporal efficiency refers to the percent of the total time–area available in the study that would have been closed to achieve the bycatch reduction.

Each of the metrics separately has information useful to managers, but none conveys the overall utility of the measure by themselves. As such, we also provide a summary metric, the SUM:

| [1] |

The SUM is a hurdle metric that requires that the bycatch reduction target be met before allowing further comparison of the spatiotemporal efficiency of the measures. The hurdle is applied to ensure that consideration of conservation (i.e., bycatch reduction) is not lost to either catch affected or space-time efficiency. When the bycatch reduction target is not met (i.e., BR < Reduction Target), the SUM is not applicable. The metric conveys information about efficacy and efficiency of the management measures. As the ratio of bycatch reduced to catch affected increases, the numerator goes to infinity. Alternatively, as bycatch reduction efficiency decreases, it goes to zero. The denominator [i.e., the spatiotemporal efficiency metric (STE)] is a proxy for impact on fishermen. The actual effect of a closure on an individual fisherman will vary greatly based on physical, fiscal, and social factors that are far beyond the scope of this paper to incorporate. However, the metric operates under the assumption that fishermen prefer fewer restrictions on their ability to fish, particularly to the time and area in which they are permitted to fish. As the percentage of the fishery (in time and space) required to reach the bycatch reduction goal decreases (i.e., as the spatiotemporally efficiency of the measure increases), the denominator approaches 0 and the SUM approaches infinity. Thus, the metric increases with bycatch reduction efficiency and spatiotemporal efficiency.

SI Methods

Data.

High-resolution haul data were obtained from the Northeast Fisheries Observer Program for the Northeast Multispecies Fishery. Specifically, data waivers for 36 vessels were obtained from fishermen of the Georges Bank Cod Fixed Gear Sector, affording access to high spatiotemporal resolution fishing effort and catch data. The observer data spanned 6 y (2005–2010) and contained information on 1,110 gillnet hauls, including 9,343 catch records (i.e., species by haul and disposition of the catch). Records with no catch or no information on species, location, or mesh size were removed. Furthermore, to develop a specific scenario for the hypothetical closures, we focus this analysis on the large mesh stand-up gillnets (i.e., gillnets with mesh size less than 8 in and not using tie-downs; n = 455) that are primarily used when targeting Atlantic cod. In each case, the objective of the closure is to minimize catch of juvenile Atlantic cod while maximizing the percent of adult Atlantic cod catch taken.

Development of Annual and Seasonal Static Closures.

We developed optimized annual and monthly static closures using Marxan (21) (no software was necessary to determine the optimal monthly full-fishery closure). Marxan is a conservation planning software tool that attempts to efficiently solve a minimum set reserve design problem (although see ref. 21 for other more recent and novel uses). That is, it attempts to efficiently select reserve sites that include various types of features such that targets for those features are met while a cost is minimized. This function has been described mathematically (53) as follows:

subject to the following:

The first term represents the cost c of including site i in the reserve set, across all sites Ns. This value is multiplied by a binomial variable x for site i (i.e., 0 or 1) representing whether the site was included in the reserve set. The second term adds a penalty based on the configuration of the reserve set. A boundary multiplier b is applied to a penalty generated relative to the connectivity cv between any two sites (i, h) contained in the reserve set. The terms xi(1 − xh) again use a binomial control variable to ensure that only distances between pairs of sites included in the reserve set are included in the penalty. Marxan attempts to minimize these costs subject to the need to meet a specific goal G for feature j, across all sites Ns. Following the previous examples, it does this by summing the quantity r of feature j in site i, and multiplying it by the binomial control variable xi.

Although the reserve configuration penalty [boundary length modifier (BLM); i.e., a penalty based on the sum of the lengths of the perimeters of all areas in the reserve network] is important for reserve sets considering larval transport or other movement patterns, or that need to cluster sites to make compliance and enforcement easier, there are circumstances that may not require such constraints. For instance, in their comparison of various quasidynamic closures, Grantham et al. (42) do not include the configuration penalty. Their reserve set was meant to capture a target level of the overall bycatch occurring in the fishery while minimizing any effect on the catch of commercial species. Neither the feature (bycatch) nor the cost (target catch) have movement characteristics that were meant to be considered in the reserve set, and as such it may have been ecologically reasonable for the authors to ignore the configuration penalty. However, their reserves would still require enforcement, and thus the study might have benefited from the use of a configuration penalty (as use of the penalty would result in smaller, more compact reserve sets).

In the present study, we consider a range of configuration penalties to determine whether a BLM improves the efficiency metric proposed below. So, although this study follows Grantham et al. (42) in adding a monthly time step t (for the seasonal closures), we keep the configuration penalty:

subject to the following:

The new variable t has been added, referencing the time t at which the site i was selected. The temporal resolution used in this study is a trade-off between the ability to make fair comparisons with the methods used in the other closures, which have time steps as fine as 1 d, and the validity of using such a fine time step considering the potentially large interannual variability in when bycatch occurs.

The target was a percentage of total juvenile catch in the dataset. Juvenile catch is recorded in the Northeast Fisheries Observer Program data with a specific disposition code (“RegsSmall”) and is thus easily identifiable. Cost was calculated as the percentage of target catch affected. This assumes that fishing effort is reduced by the closures rather than shifted. This assumption is difficult to justify in most implementations of time–area closures, but in this circumstance we are comparing closures using the same assumption across the board. Thus, we assume not that fishing effort is reduced, but that the shift in fishing effort due to any of the closures would have similar results. Because we are only considering a single gear type over a small area, we believe this assumption is reasonable.

The initial Marxan runs were all parameterized with a zero BLM (the model parameter that determines the weight of the penalty based on the ratio of the area of the closure to the length of its perimeter) and a target of 60% reduction of bycatch to be able to compare them to the efficacy of the move-on rules. Results for runs where the target was allowed to vary between 10% and 100% bycatch reduction and where the BLM was allowed to range between 0.00001 and 100 were also run. In both cases where the BLM was allowed to vary (i.e., monthly and annual time–area closures), the efficiency of the closure improved (SUM = +0.1 and +0.4 log units, respectively; Table S1), even though the percent catch affected also increased (11.5% and 21.6%, respectively). Similarly, the reduction ratio improved (i.e., increased) when the target was not constrained (monthly time–area = 44.0%; annual time–area = 46.1%; monthly full-fishery closure = 7.5%), but the overall percent bycatch reduction was lower in each case as well (−66.8%, −25.8%, and −46.0%, respectively). As none of the BLM-optimizing runs resulted in a set of closures that achieved the target reduction, the results for those measures are not compared against those that did achieve the target.

Development of Grid-Based “Hot-Spot” Closures.

Development of grid-based hot-spot closures was similar to the existing validation methods used to identify the effect of real-time closures based on move-on rules (5) and were meant to mimic (to the degree possible) the methods used by previous studies (12). A 5 × 10-km grid was overlaid on the cleaned Fixed Gear Sector large-mesh anchored gillnet data (excluding those nets in which the tops were tied to the bottom, which are used to target flounder) from 2005 to 2010. We then developed an R script to iteratively sorted the data by date. When a set with a catch of juvenile cod greater than a predefined threshold was encountered, the cell in which it occurred was closed to fishing the next day. Multiple juvenile catch thresholds were tested: 0, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 lb. Similarly, we tested 1-d closures and week-long closures. Last, we tested the same scenarios on the 10 × 10-km grid used for the Marxan-based closures. The threshold producing the best SUM was selected to compare with the other closure types.

Development of Real-Time Closures Based on Move-On Rules.

The methods used to implement real-time closures based on move-on rules follow those Dunn et al. (5) including the move-on distance used (2.5 km) and time (1 d) for avoiding juvenile cod). Rather than using number of events as our metric for performance, we used weight of catch. Closure effect was calculated by iterating through the dataset by time and day and removing any future sets within the time and distance indicated by the move-on rule of a set marked as containing any juvenile catch (i.e., bycatch threshold, 0 lb) (5).

Calculation of Time and Area Required by Closures.

Before comparisons between the various types of closures can be drawn, the time–area required by each closure method must first be calculated. The function used to calculate the time–area required for each type of closure will differ. For move-on rules, the total time–area required is simply the number of instances the move-on rules was implemented over the course of iterating through the dataset multiplied by the time and area used in the rule. The area of a move-on rule is found by calculating the area of a circle with radius equal to the distance used in the move-on rule. This relationship is captured by the following equation:

where k is an implementation of the move-on rule, Nk is the total number of implementations, s is the distance of the move-on rule, and t is the time lag of the move-on rule. Grid-based closures are defined similarly, but the area of an individual closure is the width and height of the grid cell (i.e., 5 × 10 or 10 × 10 km).

The time–area requirements for the static closures were based on the area within the study site that was within the selected “reserve.” However, unlike the dynamic closures, the area of the static closures vary with each time step, not with each instantiation of a rule. Thus, continuing to use the same notation, the time and area required by the closure may be described as follows:

Thus, the time requirement for a static closure is found by summing the area a of site i multiplied by a control variable describing whether the site was within the reserve set, across all sites Ns within the bounds of the study and all time steps Nt.

All analyses described above were run in R (54). Data were manipulated using the plyr (55) and reshape2 (56) packages. Spatial analyses were completed using the sp packages (57).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the fishermen of the Georges Bank Cod Fixed Gear Sector who collaborated with us, and especially to M. Sanderson and E. Brazer of the Cape Cod Fishermen’s Alliance. The manuscript was improved by constructive comments from J. Buckel, A. Read, D. Johnston, D. Hyrenbach, and two anonymous reviewers. Finally, we thank the observers of the Northeast Fisheries Observer Program and the staff of the Northeast Fisheries Science Center for their support. This analysis could not have been performed without their incredible work. This paper is a product of the NF-UBC Nereus Program, and D.C.D. and A.M.B. gratefully acknowledge their support for this work.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Average price of cod for the years 2005–2010 derived by dividing the total value of cod landed ($152,013,619) in New England by total landings (99,713,856 lb). Data were downloaded from the National Marine Fisheries Service Annual Commercial Landing Statistics website (https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/commercial-fisheries/commercial-landings/annual-landings/index).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1513626113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Larkin PA. Concepts and issues in marine ecosystem management. Rev Fish Biol Fish. 1996;6(2):139–164. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gislason H, Sinclair M, Sainsbury K, O’Boyle R. Symposium overview: Incorporating ecosystem objectives within fisheries management. ICES J Mar Sci. 2000;57(3):468–475. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pikitch EK, et al. 2004. Ecosystem-based fishery management. Science 305(5682):346–347.

- 4.Link JS. What does ecosystem-based fisheries management mean? Fisheries (Bethesda, Md) 2002;27(4):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn DC, et al. Empirical move-on rules to inform fishing strategies: A New England case study. Fish Fish. 2014;15(3):359–375. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn DC, Boustany AM, Halpin PN. Spatio-temporal management of fisheries to reduce by-catch and increase fishing selectivity. Fish Fish. 2011;12(1):110–119. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewison R, et al. Dynamic ocean management: Identifying the critical ingredients of dynamic approaches to ocean resource management. Bioscience. 2015;65(5):486–498. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maxwell SM, et al. Dynamic ocean management: Defining and conceptualizing real-time management of the ocean. Mar Policy. 2015;58:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobday AJ, et al. Dynamic ocean management: Integrating scientific and technological capacity with law, policy and management. Stanford Environ Law J. 2014;33(2):125–165. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little AS, Needle CL, Hilborn R, Holland DS, Marshall CT. Real-time spatial management approaches to reduce bycatch and discards: Experiences from Europe and the United States. Fish Fish. 2015;16(4):576–602. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bethoney ND, Schondelmeier BP, Stokesbury KDE, Hoffman WS. Developing a fine scale system to address river herring (Alosa pseudoharengus, A. aestivalis) and American shad (A. sapidissima) bycatch in the U.S. Northwest Atlantic mid-water trawl fishery. Fish Res. 2013;141:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Keefe CE, DeCelles GR. Forming a partnership to avoid bycatch. Fisheries (Bethesda, Md) 2013;38(10):434–444. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources 2011. Conservation Measures 33-02, 41-02, and 42-01.1 (Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, Hobart, TAS, Australia)

- 14.Auster PJ, et al. Definition and detection of vulnerable marine ecosystems on the high seas: Problems with the “move-on” rule. ICES J Mar Sci. 2011;68(2):254–264. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howell EA, Kobayashi DR, Parker DM, Balazs GH, Polovina JJ. TurtleWatch: A tool to aid in the bycatch reduction of loggerhead turtles Caretta caretta in the Hawaii-based pelagic longline fishery. Endanger Species Res. 2008;5(1):267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobday AJ, Hartmann K. Near real-time spatial management based on habitat predictions for a longline bycatch species. Fish Manag Ecol. 2006;13(6):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hobday AJ, Hartog JR, Timmiss T, Fielding J. Dynamic spatial zoning to manage southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) capture in a multi-species longline fishery. Fish Oceanogr. 2010;19(3):243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langton RW, Auster PJ, Schneider DC. A spatial and temporal perspective on research and management of groundfish in the northwest Atlantic. Rev Fish Sci. 1995;3(3):201–229. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haury LR, McGowan JA, Wiebe PH. Patterns and processes in the time-space scales of plankton distributions. In: Steele JH, editor. Spatial Pattern in Plankton Communities. Plenum Press and NATO Scientific Affairs Division; New York: 1978. pp. 277–327. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stommel H. 1963. Varieties of oceanographic experience. Science 139(3555):572–576.

- 21.Bainbridge R. The size, shape and density of marine phytoplankton concentrations. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1957;32(I):91–115. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele JH, editor. Spatial Pattern in Plankton Communities. Plenum; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denman KL, Gargett AE. Time and space scales of vertical mixing and advection of phytoplankton in the upper ocean. Limnol Oceanogr. 1983;28(5):801–815. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzella A, Haynes PH. Small-scale spatial structure in plankton distributions. Biogeosciences. 2007;4(2):173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Legendre L, Demers S. Towards dynamic biological oceanography and limnology. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1984;41(1):2–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin AP. Phytoplankton patchiness: The role of lateral stirring and mixing. Prog Oceanogr. 2003;57(2):125–174. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prairie JC, Sutherland KR, Nickols KJ, Kaltenberg M. Biophysical interactions in the plankton: A cross-scale review. Limnol Oceanogr Fluids Environ. 2012;2(1):121–145. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann KH. Physical oceanography, food chains, and fish stocks: A review. ICES J Mar Sci. 1993;50(2):105–119. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croll DA, et al. From wind to whales: Trophic links in a coastal upwelling system. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2005;289:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutchinson G. The concept of pattern in ecology. Proc Acad Nat Sci Philadelphia. 1953;105:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hixon MA. Competitive interactions between California reef fishes of the genus Embiotoca. Ecology. 1980;61(4):918–931. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross ST. Resource partitioning in fish assemblages: A review of field studies. Copeia. 1986;1986(2):352–388. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Josse E, Bach P, Dagorn L. Simultaneous observations of tuna movements and their prey by sonic tracking and acoustic surveys. Hydrobiologia. 1998;371:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hazen EL, Nowacek DP, St Laurent L, Halpin PN, Moretti DJ. The relationship among oceanography, prey fields, and beaked whale foraging habitat in the Tongue of the Ocean. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radakov DV. Schooling in the Ecology of Fish. Wiley; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parrish JK, Edelstein-Keshet L. 1999. Complexity, pattern, and evolutionary trade-offs in animal aggregation. Science 284(5411):99–101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Goodale E, Beauchamp G, Magrath RD, Nieh JC, Ruxton GD. Interspecific information transfer influences animal community structure. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25(6):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maxwell SM, Morgan LE. Foraging of seabirds on pelagic fishes: Implications for management of pelagic marine protected areas. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2013;481:289–303. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acheson JM. Anthropology of fishing. Annu Rev Anthropol. 1981;10(1):275–316. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Little LR, et al. Information flow among fishing vessels modelled using a Bayesian network. Environ Model Softw. 2004;19(1):27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Putten IE, et al. Theories and behavioural drivers underlying fleet dynamics models. Fish Fish. 2012;13(2):216–235. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grantham H, Petersen S, Possingham H. Reducing bycatch in the South African pelagic longline fishery: The utility of different approaches to fisheries closures. Endanger Species Res. 2008;5:291–299. [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Keefe CE, Cadrin SX, Stokesbury KDE. Evaluating effectiveness of time/area closures, quotas/caps, and fleet communications to reduce fisheries bycatch. ICES J Mar Sci. 2013;71(5):1286–1297. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLeod K, Lubchenco J, Palumbi S, Rosenberg A. 2005 Scientific Consensus Statement on Marine Ecosystem-Based Management (Communication Partnership for Science and the Sea, Signed by 221). Available at compassonline.org/?q=EBM. Accessed November 5, 2014.

- 45.Levin SA. Ecosystems and the biosphere as complex adaptive systems. Ecosystems. 1998;1(5):431–436. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilman EL, Dalzell P, Martin S. Fleet communication to abate fisheries bycatch. Mar Policy. 2006;30(4):360–366. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brodziak J, Link J. Ecosystem-based fisheries management: What is it and how can we do it? Bull Mar Sci. 2002;70(2):589–611. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francis RC, Hixon MA, Clarke ME, Murawski SA, Elizabeth M. Ten commandments for ecosystem-based fisheries scientists. Fisheries (Bethesda, Md) 2007;32(5):217–233. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long RD, Charles A, Stephenson RL. Key principles of marine ecosystem-based management. Mar Policy. 2015;57:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levin SA, Lubchenco J. Resilience, robustness, and marine ecosystem-based management. Bioscience. 2008;58(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bjorkland R, et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of rockfish bycatch in US West Coast groundfish fisheries: Opportunities for reducing incidental catch of depleted species. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2015;72(12):1835–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall SJ. 2002. Area and Time Restrictions. Fisheries Managers Handbook: Management Measures and Their Application. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, ed Cochrane K (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome), No. 424, pp 49–74.

- 53.Ball I, Possingham HP, Watt ME. Spatial Conservation Prioritisation: Quantitative Methods and Computational Tools. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2009. Marxan and relatives: Software for spatial conservation prioritisation; pp. 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 54.R Core Team 2014 R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available at www.r-project.org/. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 55.Wickham H. The split-apply-combine strategy for data analysis. J Stat Softw. 2011;40(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wickham H. Reshaping data with the reshape package. J Stat Softw. 2007;21(12):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bivand RS, Pebesma E, Gomez-Rubio V. Applied Spatial Data Analysis with R. 2nd Ed Springer; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]