Significance

Inactivating nuclear corepressor 1 (NCoR) mutations have been found in human tumors. Here, we report that NCoR has a tumor-suppressive role, inhibiting extravasation, metastasis formation, and tumor growth in mice. These changes are related to repressed transcription of genes associated with increased metastasis and poor prognosis in cancer patients. An autoregulatory loop maintains NCoR gene expression, suggesting that NCoR loss can be propagated, contributing to tumor progression in the absence of NCoR gene mutations. The nuclear receptor thyroid hormone receptor β1 increases NCoR expression, and this induction is essential in mediating its tumor-suppressive actions. Both are reduced in human hepatocarcinoma and aggressive breast cancer tumors, identifying NCoR as a potential molecular target for the development of novel therapies.

Keywords: nuclear corepressor 1, thyroid hormone receptor, tumor growth, metastasis, transcription

Abstract

Nuclear corepressor 1 (NCoR) associates with nuclear receptors and other transcription factors leading to transcriptional repression. We show here that NCoR depletion enhances cancer cell invasion and increases tumor growth and metastatic potential in nude mice. These changes are related to repressed transcription of genes associated with increased metastasis and poor prognosis in patients. Strikingly, transient NCoR silencing leads to heterochromatinization and stable silencing of the NCoR gene, suggesting that NCoR loss can be propagated, contributing to tumor progression even in the absence of NCoR gene mutations. Down-regulation of the thyroid hormone receptor β1 (TRβ) appears to be associated with cancer onset and progression. We found that expression of TRβ increases NCoR levels and that this induction is essential in mediating inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by this receptor. Moreover, NCoR is down-regulated in human hepatocarcinomas and in the more aggressive breast cancer tumors, and its expression correlates positively with that of TRβ. These data provide a molecular basis for the anticancer actions of this corepressor and identify NCoR as a potential molecular target for development of novel cancer therapies.

Corepressors play a central role in bridging chromatin-modifying enzymes and transcription factors (1). NCoR (nuclear corepressor 1) and the homologous protein SMRT (silencing mediator or retinoic and thyroid hormone receptors or NCoR2) were identified by their interaction with unliganded thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) and retinoic acid receptors (2, 3), although later studies demonstrated that they also could bind to other transcription factors (4). NCoR and SMRT belong to large complexes that contain histone deacetylases (HDACs), thereby inducing chromatin compaction and gene silencing (4–7). Although these corepressors interact with multiple HDACs, HDAC3 plays a key role in mediating their actions (8, 9) and is essential for repression by TRs (10, 11).

As expected from their prevalent role in integrating the action of many transcription factors, NCoR and HDAC3 affect numerous developmental and homeostatic processes (12). In addition, there is increasing evidence that NCoR could play a significant role in cancer. Alterations in NCoR expression or subcellular localization have been linked to various solid tumors. Thus, reduced NCoR expression has been associated with invasive breast tumors (13, 14), shorter relapse-free survival (15), and resistance to antiestrogen treatment (16). Unbiased pathway analysis recently has revealed mutations of NCoR (17, 18) among the driver mutations in breast tumors (19). The human NCoR gene is located on a region of chromosome 17p frequently deleted in hepatocarcinoma (HCC) (20, 21), suggesting that loss of this corepressor could drive liver cancer also. In agreement with this idea, liver-specific deletion of HDAC3 caused spontaneous development of HCC in mice, showing its essential role in the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability (22). Furthermore, the expression of HDAC3 and NCoR was down-regulated in a subset of human HCCs (22). All these findings suggest that NCoR could be an important suppressor of cancer initiation or progression, but the mechanisms by which the corepressor exerts its tumor-suppressing role have not yet been examined.

TRs, and in particular TRβ1, can act as tumor suppressors (23). We have shown that this receptor retards tumor growth and suppresses invasion, extravasation, and metastasis formation in nude mice (23–26). These tumor-suppressing effects are associated with a decreased expression of prometastatic genes (23). The role of TRβ1 appears to be particularly relevant in liver cancer. Thus, thyroid hormones binding to TRβ1 induce regression of carcinogen-induced nodules, reducing the incidence of HCC and lung metastasis in rodents (27, 28), and TRβ1 down-regulation appears to be associated with HCC onset and progression (29). In addition, aberrant TRs that act as dominant-negative inhibitors of wild-type TR activity and that have altered association with corepressors have been found frequently in human HCCs (30, 31).

Here, we show that NCoR depletion enhances cellular invasion in vitro and increases tumor growth and the metastatic potential in nude mice. These actions are related to the regulation of genes associated with metastatic growth and poor outcome in cancer patients. Furthermore, we demonstrate the existence of a positive autoregulatory loop that maintains NCoR gene expression. NCoR depletion results in heterochromatinization and long-term silencing of NCoR transcription. Silencing could represent an important oncogenic mechanism in tumors in which inactivating mutations in the NCoR gene are not present. Finally, we show that induction of NCoR is an essential mediator of the tumor-suppressing actions of TRβ1 and that both are down-regulated in human HCC and in estrogen receptor-negative (ER−) breast tumors, demonstrating a positive correlation between the expression of the receptor and the corepressor. Taken together, our results define NCoR as a potent tumor suppressor and as a potential target for cancer therapy.

Results

NCoR Represses Expression of Prometastatic Genes.

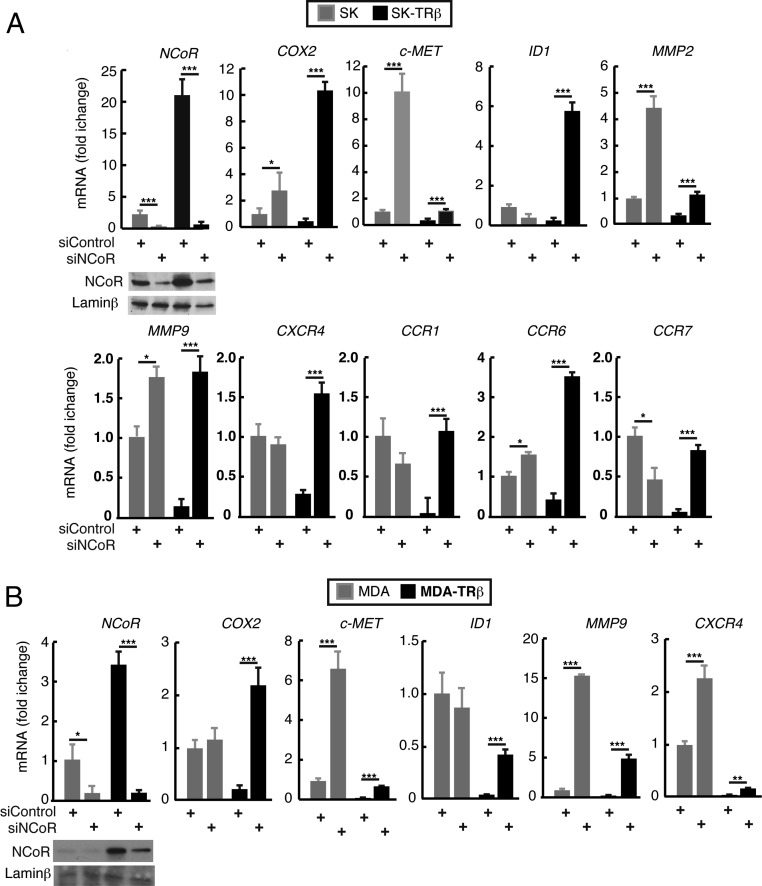

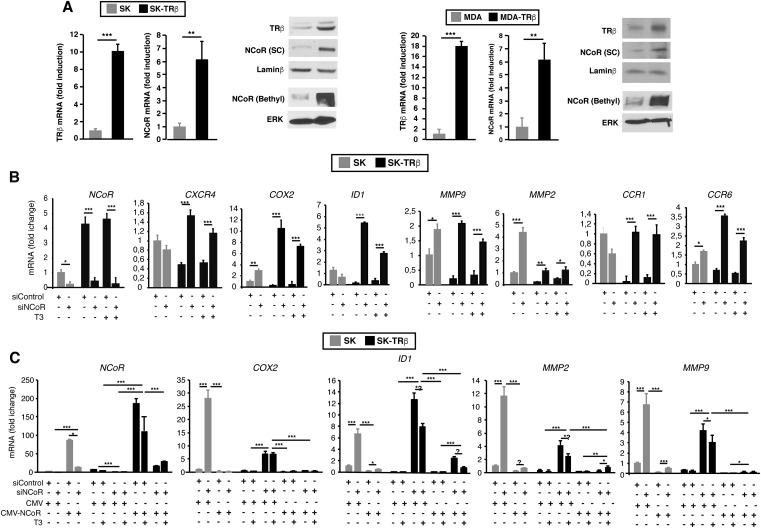

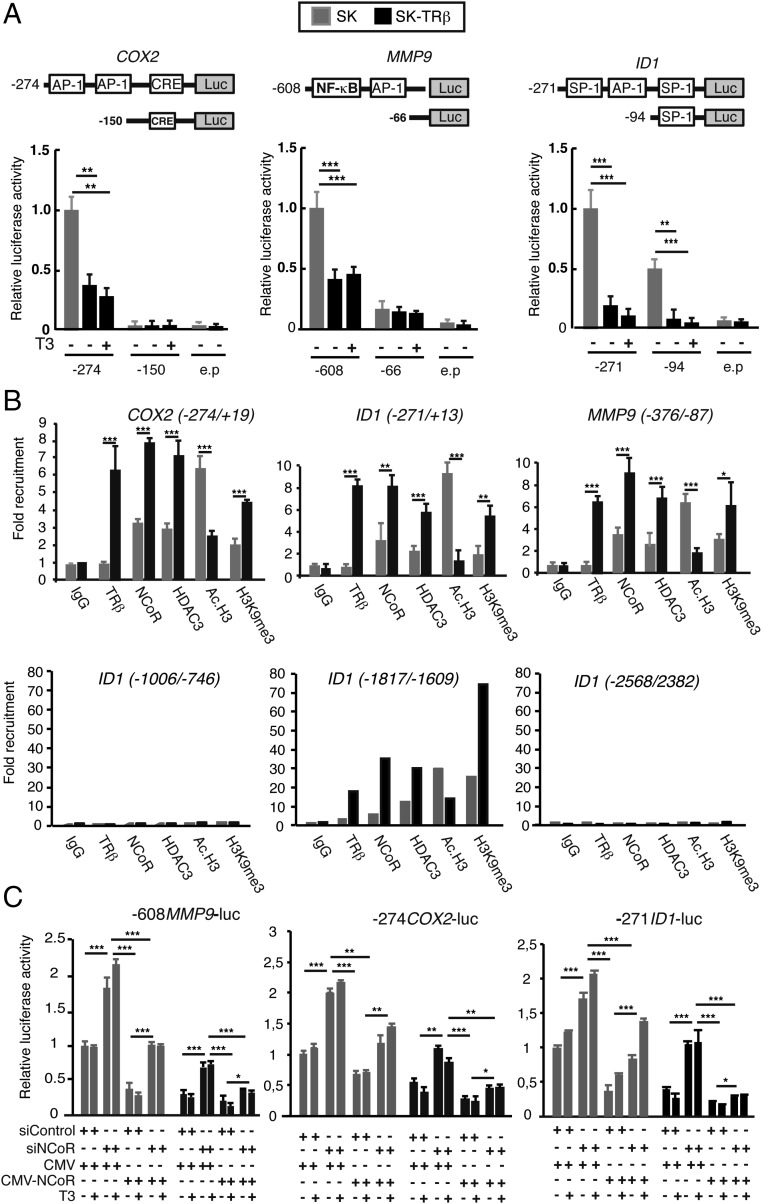

mRNAs of selected prometastatic genes, including cyclooxigenase 2 (COX2), DNA-binding protein inhibitor 1 (ID1), C-MET, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)2, MMP9, CXCR4, CCR1, CCR6, and CCR7, were measured in SK-hep1 (SK) cells transfected with a control siRNA or with an NCoR-specific siRNA. These cells were derived from a patient with liver adenocarcinoma and recently have been shown to have an oncogenic mesenchymal stem cell phenotype (32). Most of these genes were significantly increased upon NCoR depletion in SK cells (Fig. 1A) and in MDA-MB-468 (MDA) breast cancer cells (Fig. 1B). Because TRβ expression significantly increased NCoR mRNA and protein levels in SK and MDA cells (Fig. S1A), and prometastatic genes are repressed by TRβ, we reasoned that increased NCoR levels could play a role in this repression. Thus, we also measured prometastatic gene expression in SK-TRβ and MDA-TRβ cells, finding that the repressive effect of TRβ was reversed to a significant extent, or even totally in some cases, in NCoR-depleted cells (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, most of the effect of TRβ appears to be ligand independent, because incubation with triiodothyronine (T3) had little effect on transcript levels of NCoR and prometastatic genes (Fig. S1B). Similar changes were observed in human HepG2 HCC cells and in nontumoral HH4 human hepatocytes (Fig. S2 A and B), showing that TRβ also has a role as a direct regulator of NCoR in hepatocytes and the importance of the corepressor as an inhibitor of prometastatic gene expression. NCoR overexpression in SK and SK-TRβ cells reversed the effect of the siNCoR in prometastatic gene expression, eliminating the off-target effects of the siRNA pool used (Fig. S1C). In contrast with the crucial role of NCoR, efficient knockdown of the SMRT corepressor did not increase the expression of these genes, indicating that it does not participate in their regulation (Fig. S2 C and D).

Fig. 1.

NCoR depletion increases the expression of prometastatic genes. (A) mRNA levels of prometastatic genes in SK and SK-TRβ cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR. Data (means ± SD) are expressed relative to the values obtained in SK cells transfected with siControl. A Western blot of NCoR protein levels is shown. (B) An experiment in MDA and MDA-TRβ cells similar to that shown in A.

Fig. S1.

TRβ induces NCoR expression and represses expression of prometastatic genes. (A) TRβ and NCoR mRNA (means ± SD) and protein levels in SK and MDA cells transduced with an empty vector or with a vector encoding TRβ1 (SK-TRβ and MDA-TRβ cells). NCoR levels were evaluated with two different antibodies. (B) mRNA levels (means ± SD) of the indicated genes were determined in SK and SK-TRβ cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR 72 h before and treated for 36 h in the presence and absence of 5 nM T3. (C) The cells were cotransfected with the siRNAs in the presence of an expression vector for NCoR (CMV-NCoR) or the empty vector (CMV) and transcript levels of the indicated genes (means ± SD) determined in control and T3-treated cells.

Fig. S2.

NCoR, but not SMRT, regulates the expression of prometastatic genes in several cell types. (A, Left) Transcript levels (means ± SD) of NCoR and several prometastatic genes in parental HCC HepG2 cells and in cells stably expressing TRb1 (HepG2-TRb). Cells had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 72 h previously, and mRNA levels were determined after incubation with or without T3 for 36 h, as indicated. (Right) SMRT and NCoR protein levels in the HepG2-TRb cells after the same treatments. (B) Experiments performed as in A in nontransformed HH4 hepatocytes expressing an empty vector or TRb1. (C) SMRT does not regulate the expression of prometastatic genes. mRNA levels (means ± SD) of the corepressor SMRT and the indicated prometastatic genes in SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected 72 h previously with control siRNA (siControl) or with siRNA targeting SMRT (siSMRT). (D) An experiment similar to that described in C in MDA and MDA-TRβ cells.

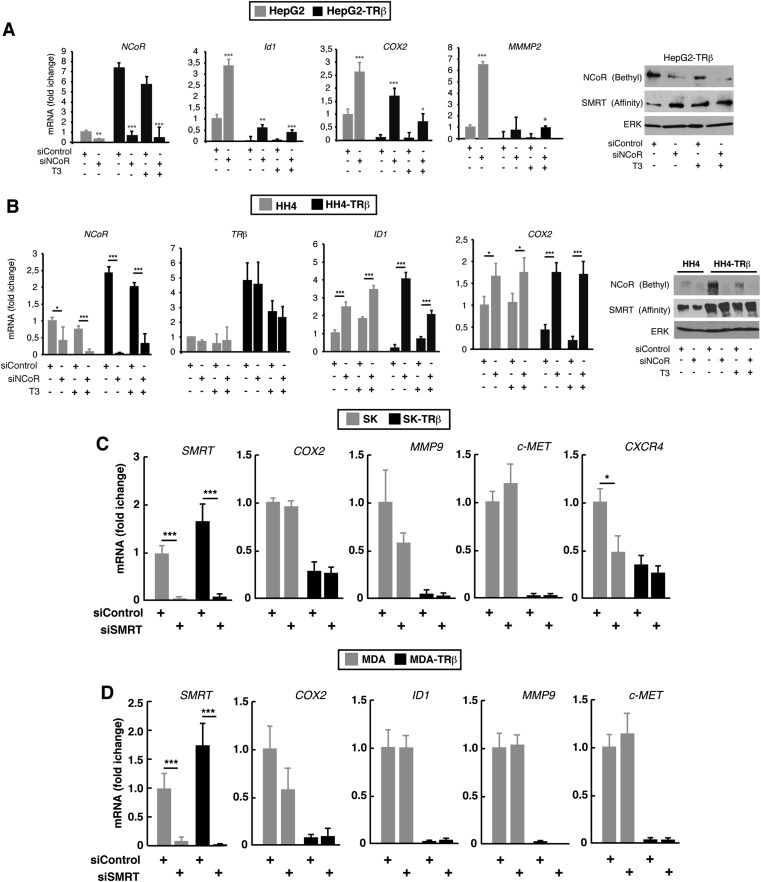

We next conducted transient transfection studies with luciferase promoter constructs of prometastatic genes in SK cells. Proximal promoter sequences of the COX2, ID1, and MMP9 genes containing binding sites for various transcription factors appear to mediate both basal promoter activity and TRβ inhibition (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, in SK-TRβ cells the receptor was constitutively bound to these sequences in ChIP assays, and NCoR and HDAC3 recruitment to the promoters was enhanced significantly in comparison with the parental cells. In parallel with this increase, histone H3 acetylation was reduced and the repressive histone marker H3K9me3 was increased in SK-TRβ cells (Fig. 2B). In the ID1 gene additional control regions have been identified (33), and although an irrelevant upstream region and the −1006/−746 control region were unaffected, the −1817/−1609 fragment also bound NCoR and TRβ, and the epigenetic changes observed were similar to those found with the more proximal promoter sequences (Fig. 2B). To analyze the functional role of NCoR in promoter regulation, the impact of NCoR gain of function and loss of function was evaluated in transfection assays. Overexpression of NCoR reduced promoter activity in SK cells to levels similar to those found in SK-TRβ cells. Conversely, NCoR depletion normalized promoter activity in the cells expressing the receptor (Fig. 2C), demonstrating the essential role of this corepressor in the inhibitory effect of TRβ on metastatic gene transcription. In addition, NCoR overexpression inhibited the stimulatory effect of siNCoR, again eliminating off-target effects of the siRNA.

Fig. 2.

NCoR represses promoter activity of prometastatic genes. (A) Transient transfection assays in SK and SK-TRβ cells with luciferase reporters of the COX2, MMP9, and ID1 promoters or an empty plasmid (e.p). Schematics of the plasmids used showing the putative binding motifs for different transcription factors are illustrated. Cells were treated with and without 5 nM T3 for 36 h as indicated. Data are means ± SD and are expressed relative to the luciferase activity obtained in untreated SK cells. (B) ChIP assays in SK and SK-TRβ cells with the antibodies and the promoter regions indicated. (C) Luciferase assays (mean ± SD) with the indicated reporter plasmids in SK and SK-TRβ cells cotransfected with siControl or siNCoR in the presence of an expression vector for NCoR (CMV-NCoR) or the empty vector (CMV). Luciferase activity (means ± SD) was determined in cells treated with and without T3.

NCoR Inhibits Invasion and Metastasis.

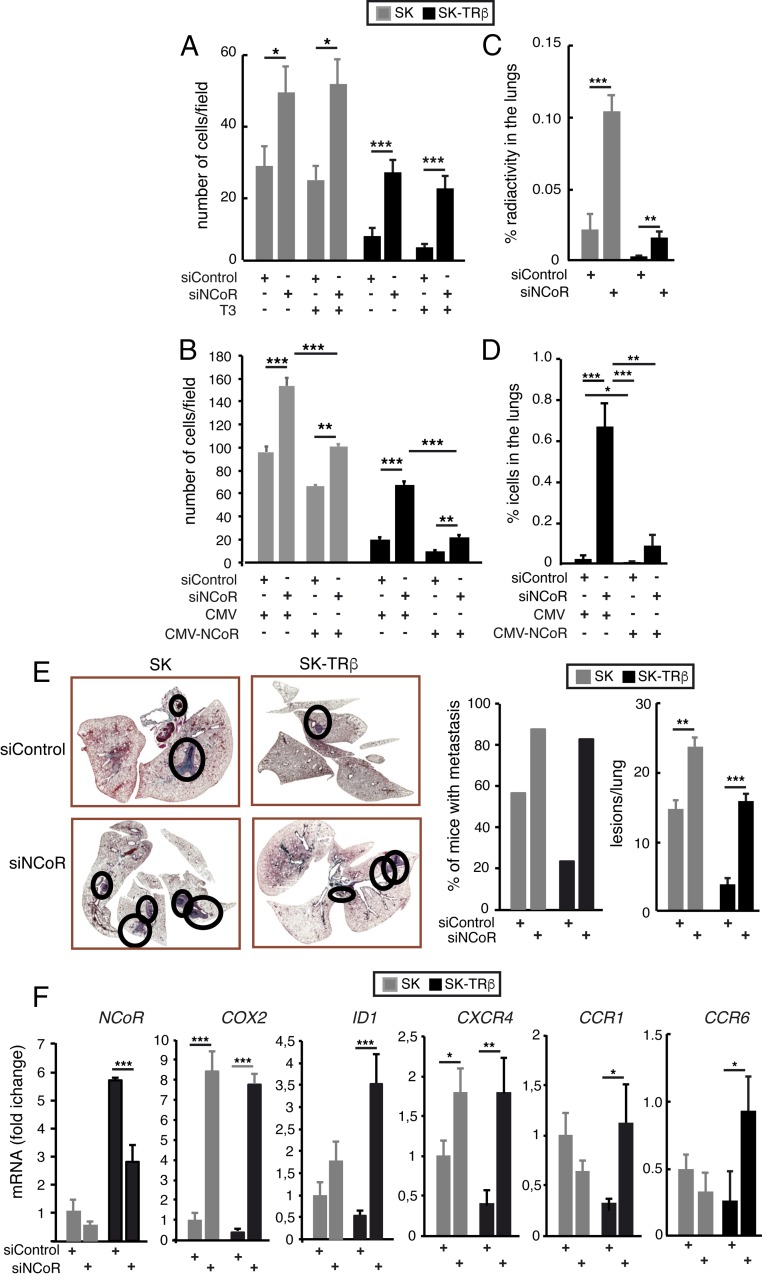

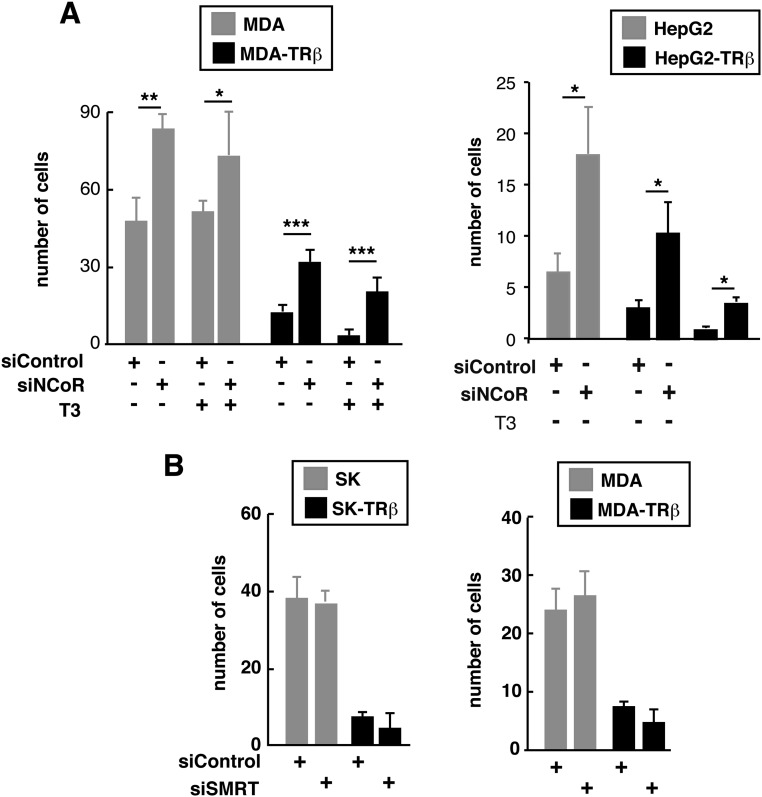

The identification of NCoR as an important regulator of genes that are well documented as playing a role in cancer progression suggested that this protein might play a role in invasion, tumor growth, or metastasis. Therefore we first investigated the role of NCoR in cell invasion in Transwell Matrigel assays. NCoR depletion increased the invasive capacity of SK, HepG2, and MDA cells and to a significant extent reversed the reduced invasion of TRβ in both the absence and presence of T3 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3A). NCoR overexpression reduced invasion and antagonized stimulation by siNCoR in SK and SK-TRβ cells (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the corepressor has a functional role as an inhibitor of cellular invasion and plays a critical function in mediating the repressive effect of TRβ. In contrast, depletion of SMRT had no effect (Fig. S3B), indicating that SMRT is not a regulator of invasion in these cells.

Fig. 3.

NCoR inhibits invasion, extravasation, and metastatic growth. (A) Invasion assays in Matrigel of SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 72 h previously. Invasion lasted for the last 16 h in the presence and absence of T3. The number of cells per field passing the filter (mean ± SD) was scored under the microscope and is shown on the y axis. (B) Similar assays in cells transfected as indicated with siNCoR, CMV-NCoR, or the corresponding controls. (C) Extravasation assays in nude mice of cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR. Data (mean ± SE) are expressed as the percentage of the inoculated cells found in the lung. (D) Extravasation of SK-TRβ cells transfected with siNCoR or CMV-NCoR or with the corresponding controls alone and in combination was analyzed by determination of human Alu sequences in the lungs. (E, Left) Metastatic lesions (surrounded by circles) in lungs from nude mice that had been inoculated 30 d previously via the tail vein with cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR. (Right) The percent of animals with metastases and number of lesions per lung (mean ± SE). (F) Relative transcript levels of NCoR and the indicated prometastatic genes (mean ± SD) in metastases excised from the lungs by laser-capture microdissection.

Fig. S3.

NCoR, but not SMRT, depletion enhances invasion. (A) Matrigel invasion assays (means ± SD) in parental and TRβ-expressing MDA and HepG2 cancer cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR for 72 h and incubated with or without T3. Invasion in the presence and absence of T3 took place during the final 16 h. (B) Invasion assays (means ± SD) in SK and MDA cells transfected with siControl or siSMRT.

To analyze whether NCoR also could play a role in cell invasion in vivo, SK and SK-TRβ cells transfected with control or NCoR siRNAs were injected into the tail vein of nude mice. NCoR depletion increased the amount of SK cells present in the lungs very significantly and increased the extravasation of TRβ-expressing cells to levels similar to those found in the parental cells (Fig. 3C). The augmented extravasation of TRβ-expressing cells transfected with siNCoR was again reversed by NCoR expression (Fig. 3D), demonstrating the specificity of the effects of the corepressor on the invasive properties of the cancer cells in vivo. Because NCoR limits cancer cell extravasation, it should act as an inhibitor of metastatic growth. Thus we next analyzed the effect of NCoR depletion in the formation of lung metastasis by SK and SK-TRβ cells 30 d after i.v. injection. The incidence of metastasis was increased in mice inoculated with SK cells transfected with siNCoR. Furthermore, SK-TRβ cells showed a reduced metastatic capacity (24), but this capacity increased significantly in the absence of NCoR. Both the incidence of lung metastasis and the number of metastatic lesions were enhanced significantly in the absence of the corepressor (Fig. 3E). Therefore, NCoR suppresses the metastatic potential in vivo. We next isolated the metastatic lesions by laser-capture microdissection to analyze the expression of NCoR and prometastatic genes. Strikingly, even at 30 d postinjection NCoR transcripts were significantly reduced in the metastases formed by cells originally transfected with siNCoR. Reduction was particularly apparent in metastases from SK-TRβ cells that expressed higher levels of the corepressor. Furthermore, prometastatic genes were derepressed in the metastasis after NCoR depletion (Fig. 3F). The finding that NCoR knockdown with siRNA lasted for a very long time suggests the existence of a positive autoregulatory loop that maintains NCoR gene expression.

Tumors Formed by NCoR-Depleted Cells Are Bigger and More Invasive.

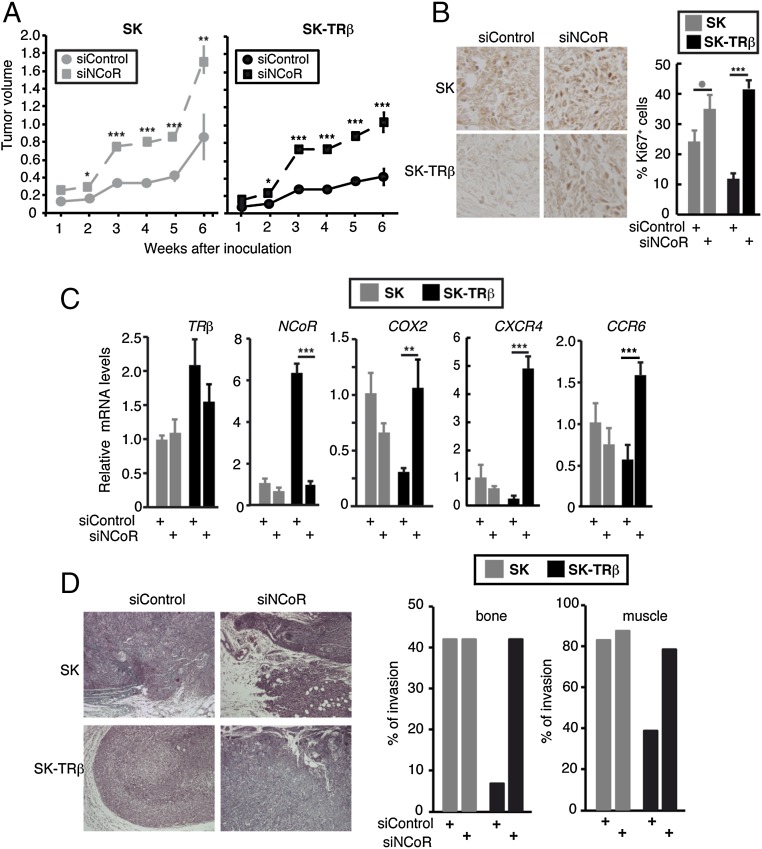

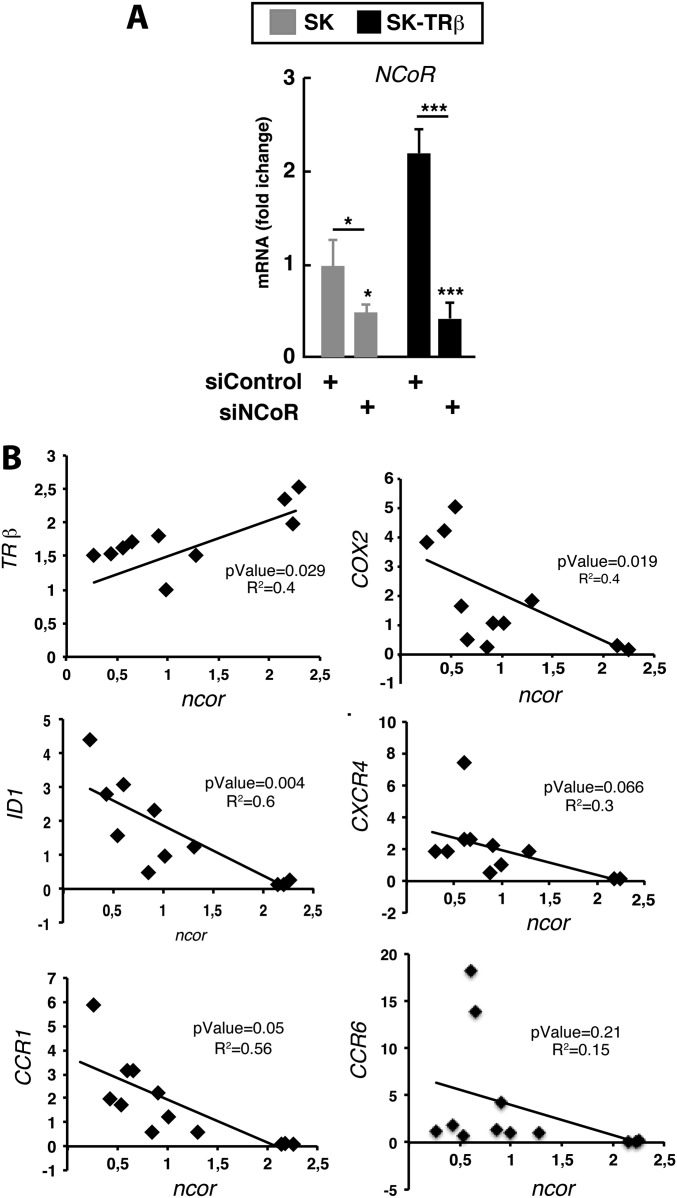

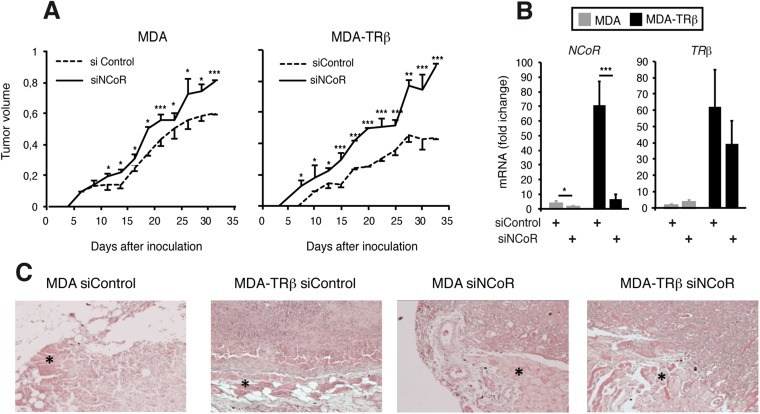

To examine the tumor-suppressive effect of NCoR in vivo further, we conducted xenograft studies with SK and SK-TRβ cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR. NCoR depletion increased tumor volume in both parental and TRβ-expressing cells. Differences were observed as early as 2 wk after inoculation and were maintained during the whole experimental period (6 wk) (Fig. 4A). In explants from tumors obtained at 2 wk, NCoR depletion was maintained in both SK and SK-TRβ cells. Furthermore, there was a significant positive correlation between the levels of NCoR and TRβ mRNAs and an inverse relationship between expression of the corepressor and the mRNA levels of several prometastatic genes, again indicating the crucial role of NCoR in prometastatic gene expression (Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

NCoR inhibits tumor growth and invasion. (A) Volume of the tumors (mean ± SE) after inoculation of cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR into nude mice. (B) Immunohistochemistry of Ki67 and the percentage of Ki67+ cells (mean ± SE) in tumors excised 6 wk after inoculation. (C) Relative transcript levels of TRβ, NCoR, and the indicated prometastatic genes (mean ± SE) in the tumors. (D, Left) Representative Masson´s trichrome staining of tumors, showing that tumors formed by cells transfected with siNCoR were more invasive. (Right) The percentage of tumors that infiltrated bone and muscle.

Fig. S4.

NCoR expression correlates with TRβ and prometastatic gene expression in tumor explants. (A) NCoR mRNA (means ± SD) in explants obtained from tumors 2 wk after nude mice were inoculated with SK and SK-TRβ cells that previously had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR. (B) Levels of TRβ mRNA and the indicated genes in each explant were determined and plotted against the corresponding value of NCoR mRNA. Linear regressions were calculated, showing a positive correlation between NCoR and TRβ and a negative correlation of NCoR with prometastatic genes in the explants.

The increased size of tumors formed by cells transfected with siNCoR correlated with a higher proliferation rate (Fig. 4B). Tumors that originated from parental SK cells were more proliferative than those formed by SK-TRβ cells, and NCoR depletion markedly increased the number of Ki67+ cells. Even 6 wk after inoculation, strongly reduced NCoR mRNA levels were observed in the tumors formed by SK-TRβ cells originally transfected with siNCoR, and transcript levels of prometastatic genes were still significantly higher than in tumors that originated from cells transfected with the control siRNA (Fig. 4C). NCoR depletion also enhanced the invasive capacity of SK-TRβ tumors (Fig. 4D). Tumors formed by SK-TRβ cells were very compact and were surrounded by a pseudocapsule, which was lost in NCoR-deficient tumors that were highly infiltrative. Furthermore, the percentage of tumors invading bone and muscle was reduced by TRβ, and this protector effect was lost upon NCoR depletion (Fig. 4D). NCoR knockdown also increased the growth rate of tumors formed by inoculation of MDA and MDA-TRβ cells into nude mice (Fig. S5A), and significantly reduced NCoR transcripts also were found in the breast tumors formed by the cells that had been transfected with siNCoR 33 d previously (Fig. S5B). In addition, the noninvasive TRβ-expressing breast tumors became highly infiltrative in the absence of the corepressor (Fig. S5B). Therefore, NCoR acts not only as a suppressor of tumor growth but also as an inhibitor of tumor invasion in vivo.

Fig. S5.

NCoR inhibits growth and invasion of tumors formed by breast cancer cells. (A) Volume of the xenografts (mean ± SE) after orthotopic inoculation of MDA and MDA-TRβ cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR into the fat mammary pad of nude mice. (B) Relative transcript levels of NCoR and TRβ (mean ± SE) in the dissected tumors. (C) Representative H&E staining of the xenografts showing that tumors formed by cells transfected with siNCoR were more invasive. The asterisks mark muscle tissue. Note that the tumors originated by MDA-TRβ cells transfected with siControl were very compact and did not infiltrate the muscle. As in the case of SK-TRβ cells, this property was lost after NCoR knockdown, and tumors became invasive.

NCoR and TRβ Expression Are Reduced in Human HCC and Breast Tumors.

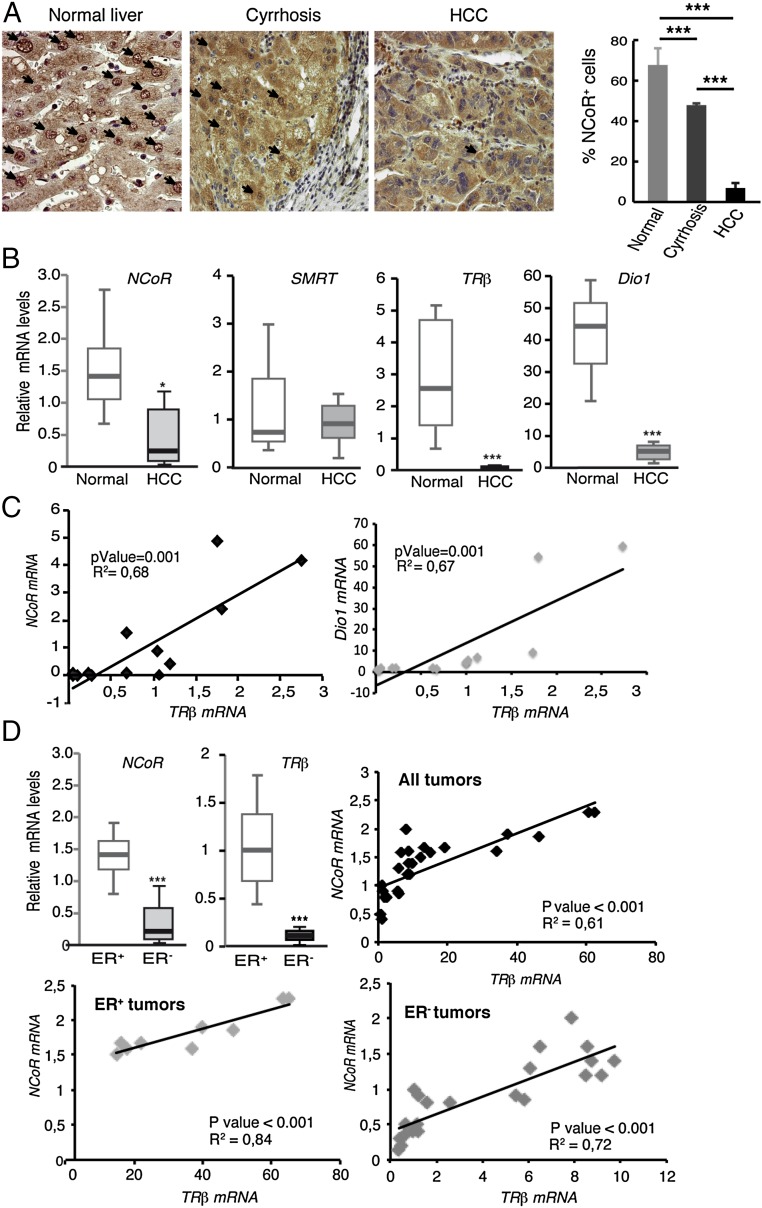

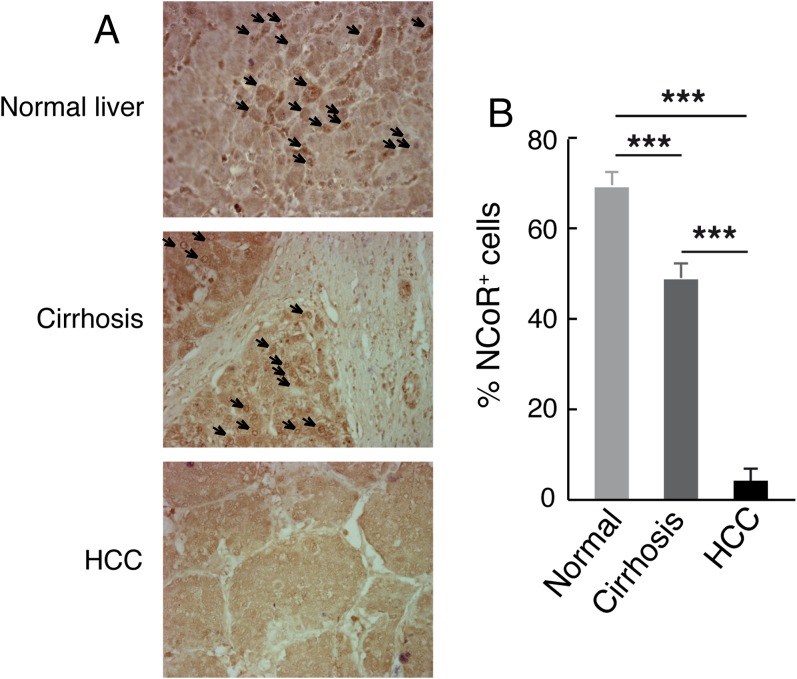

To support the role of NCoR in human cancer further, we collected human HCC and breast tumors samples. The expression of NCoR was analyzed by immunohistochemistry in the HCC, in the surrounding cirrhotic tissue, and in normal liver samples (Fig. 5A). In the normal tissue most nuclei were positive for NCoR, but this number was reduced in the cirrhotic liver and was markedly inhibited in the tumors, where less than 10% of the nuclei had detectable NCoR. These findings were confirmed by immunohistochemistry in other NCoR-specific antibodies (Fig. S6) and by mRNA analysis. The results revealed a significant decrease in NCoR mRNA in tumors compared with normal liver, whereas no differences in SMRT mRNA levels were found. TRβ transcripts also were reduced in the HCCs, and Dio1, a bona fide TR target gene in liver cells (23), showed a similar reduction (Fig. 5B). Statistical analysis found a significant positive correlation (P < 0.001) when TRβ mRNA was plotted against NCoR or Dio1 mRNAs (Fig. 5C). Strongly reduced levels of NCoR and TRβ transcripts, without changes in SMRT, also were found in RNA samples from the more aggressive ER− breast tumors as compared with ER+ tumors. Again there was a strong correlation between NCoR and TRβ transcripts (P < 0.001) that occurred independently of ER status (Fig. 5D). Taken together these data are consistent with a tumor-suppressive role for the corepressor in HCC and breast cancer and support the notion that NCoR is a downstream effector of TRβ in these tumors.

Fig. 5.

NCoR and TRβ expression in human HCC and breast cancer tumors. (A, Left) NCoR immunohistochemistry of normal liver, the surrounding cirrhotic tissue, and HCC NCoR-positive cell nuclei are indicated by arrows. (Right) The percent of NCoR-positive cells in the different groups (mean ± SD). (B) Whisker plot of NCoR, SMRT, TRβ, and Dio1 mRNAs (mean ± SD) in normal liver and HCC. (C) TRβ mRNA was plotted against the corresponding NCoR or Dio1 transcripts in each sample. The P value and linear regression coefficient obtained are shown. (D) NCoR, SMRT, and TRβ mRNAs (mean ± SD) in ER+ (n = 18) and ER− (n = 18) breast tumors. Correlation between NCoR and TRβ in all tumors as well as independently in ER+ and ER− tumors is illustrated also.

Fig. S6.

Reduced expression of NCoR in human HCC. (A) Representative NCoR immunohistochemistry of normal liver, cirrhotic tissue, and tumoral tissue performed with the NCoR antibody ab24552, which is specific for NCoR1, variant 1. NCoR-positive cell nuclei are indicated by arrows. (B) Percent of NCoR-positive cells in the different groups (mean ± SD).

Epigenetic Changes Responsible for Stable NCoR Depletion.

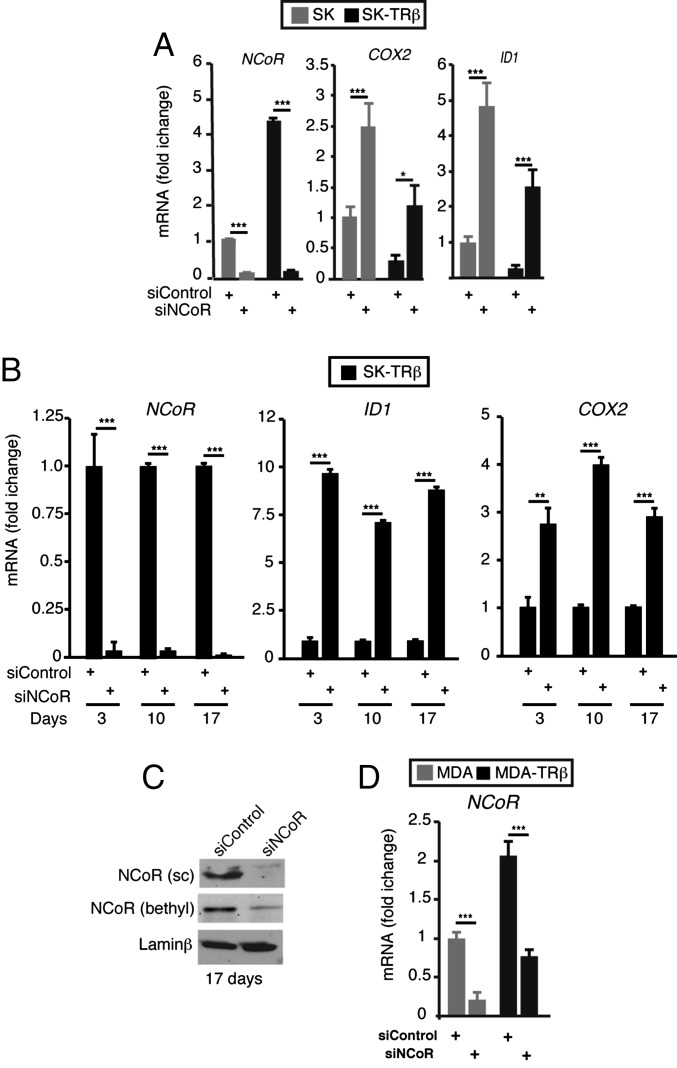

Using cultured cells, we next investigated the mechanism by which transient NCoR knockdown could lead to long-term deficiency. As shown in Fig. 6A, 17 d after siNCoR transfection, when several cell doublings had already occurred, NCoR mRNA was still depleted in SK and SK-TRβ cells. Furthermore, derepression of ID1 and COX2 mRNAs was also maintained. In fact, in SK-TRβ cells the degree of change was similar at 3, 10, and 17 d after siRNA transfection (Fig. 6B), and at these time points NCoR protein levels were reduced also (Fig. 6C). NCoR autoregulation is not an exclusive characteristic of SK cells, because NCoR mRNA levels also were depleted in MDA and MDA-TRβ cells 17 d after siNCoR transfection (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

NCoR depletion with siRNA leads to long-term reduction of NCoR gene expression. (A) NCOR, COX2, and ID1 transcripts (means ± SD) in SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 17 d previously. (B) The same mRNAs quantitated at 3, 10, and 17 d posttransfection in SK-TRβ cells. Data are means ± SD. (C) Western blot analysis of NCoR expression with Santa Cruz (SC) and Bethyl antibodies 17 d after SK-TRβ cells were transfected with siControl or siNCoR. (D) NCoR transcripts (means ± SD) in MDA and MDA-TRβ cells 17 d after transfection with siControl or siNCoR.

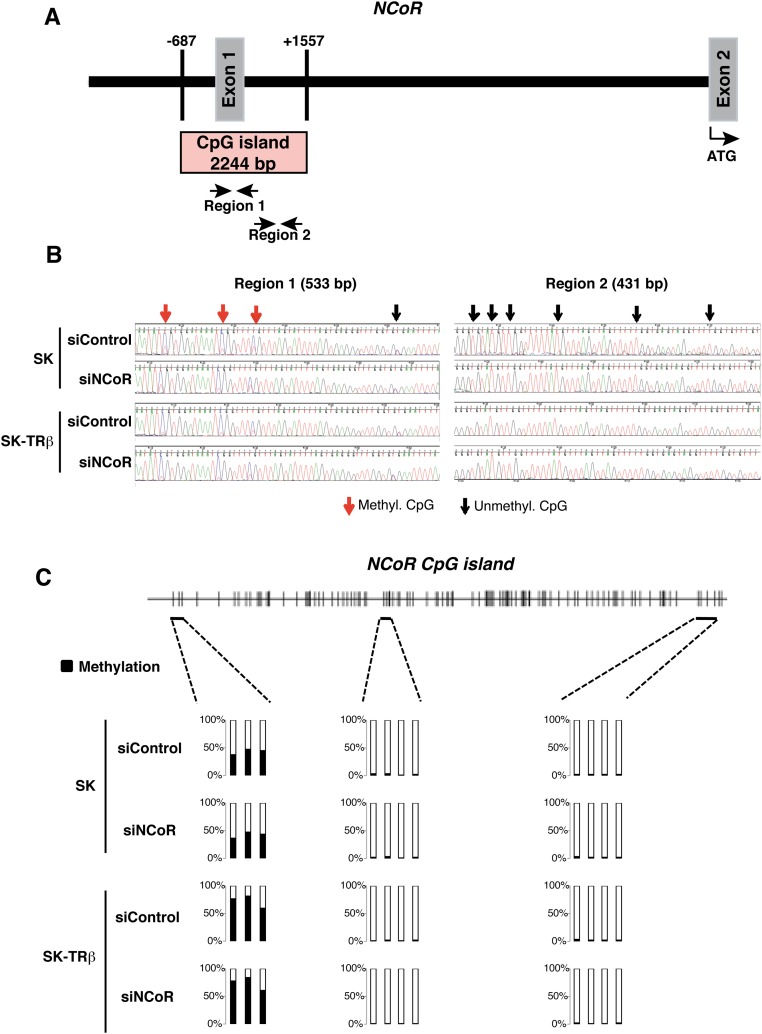

The long-term NCoR silencing obtained with the siRNA suggested the existence of an epigenetic mechanism that could maintain NCoR repression through cell generations. The most typical inheritable mechanism that could explain these results would be silencing of the NCoR gene by DNA methylation. Analysis of the NCoR gene revealed the presence of a regulatory CpG island spanning −687 to +1557 with respect to the first exon, with the ATG located in the second exon (Fig. S7A). However, bisulfite analysis of this fragment showed that the island was unmethylated to a large extent and that the same nucleotides were modified in SK and SK-TRβ cells 17 d after transfection with siControl or siNCoR (Fig. S7B). These results were confirmed by pyrosequencing (Fig. S7C), thus suggesting that increased methylation of this region was not responsible for the long-lasting repression of the NCoR gene upon siRNA transfection.

Fig. S7.

Long-lasting NCoR gene silencing does not appear to be caused by DNA hypermethylation. (A) Schematic representation of the NCoR gene indicating the presence of a regulatory CpG island located between nucleotides −687/+1557 with respect to the first exon and the position of the ATG in the second exon. (B) Methylation in the indicated regions 1 and 2 of the CpG island was determined after metabisulphite conversion of DNA obtained from SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 17 d previously. Methylated CpGs are shown by red arrows, and unmethylated CpGs are shown by black arrows. (C) Scheme of the NCoR CpG island showing the location of the regions analyzed by pyrosequencing and the percent of methylation obtained in the groups shown in B.

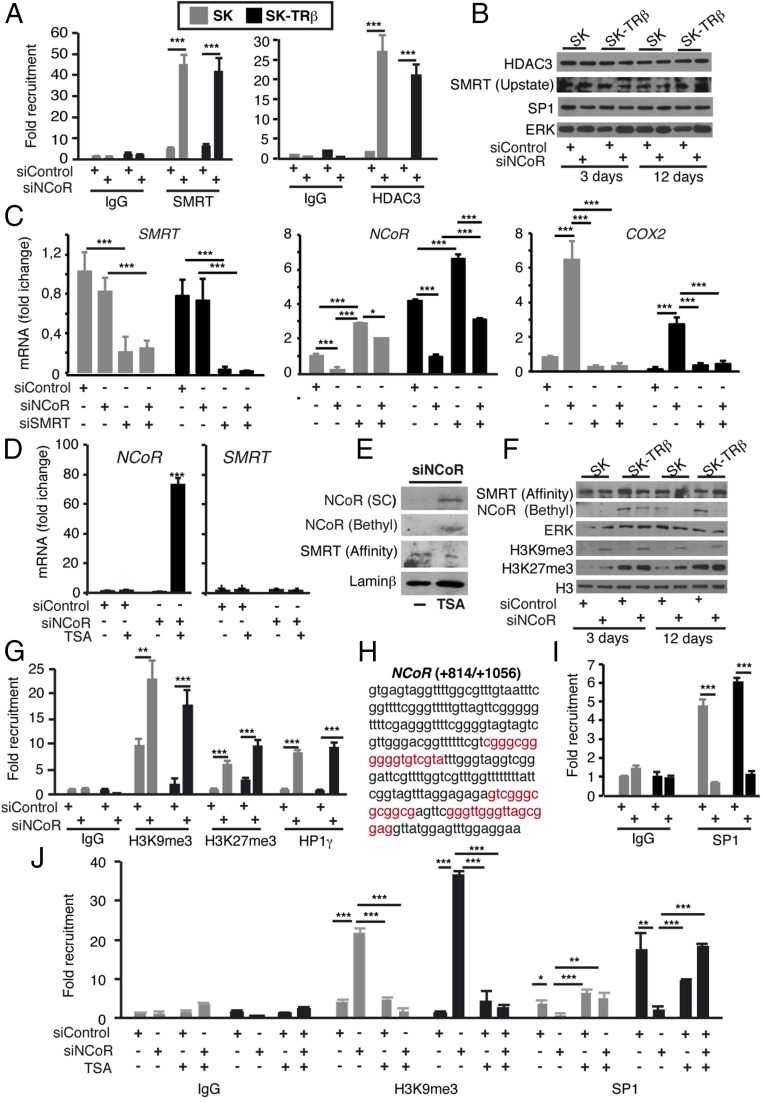

We then investigated whether recruitment of repressor proteins or increased repressive histone markers could be related to stable NCoR gene silencing in NCoR-depleted cells. Indeed, recruitment of SMRT to the +814/+1056 regulatory region of the NCoR gene increased strongly 24 d after transfection with siNCoR in SK and SK-TRβ cells (Fig. 7A). Because SMRT also silences gene expression by HDAC3 recruitment (34), there was a strong increase in HDAC3 association with the NCoR promoter (Fig. 7A). These changes occurred without alterations in the expression of HDAC3 SMRT (Fig. 7B). To test the functional significance of this pathway, we next analyzed the effect of SMRT knockdown in cells previously transfected with siNCoR. NCoR depletion did not alter SMRT mRNA levels, but the low levels of NCoR mRNA in cells transfected with siNCoR increased very significantly upon SMRT depletion, demonstrating the key role of SMRT in long-term silencing of the NCoR gene (Fig. 7C). Moreover, the enhanced expression of the NCoR target gene COX2 observed in NCoR-depleted cells was reversed, in parallel with the increased NCoR expression, when SMRT was depleted also (Fig. 7C). The importance of histone acetylation in the positive autoregulatory mechanism that maintains NCoR expression was demonstrated further by the finding that the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) was a very strong inducer of NCoR mRNA and protein expression only in cells transfected with siNCoR (Fig. 7 D and E). This effect again was specific, because it was not observed when SMRT mRNA levels were determined (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Heterochromatinization of the NCoR gene after NCoR depletion with siRNA. (A) ChIP assays of SMRT and HDAC3 with the +814/+1056 region of the NCoR gene with respect to the first exon in SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 24 d previously. (B) Western blot analysis of HDAC3, SMRT (with Upstate antibodies), SP1, and ERK in SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 3 and 12 d previously. (C) SMRT, NCoR, and COX2 transcripts (means ± SD) in cells transfected with siControl or siNCoR for 17 d and with siSMRT for the final 3 d. (D) NCoR and SMRT mRNA levels in SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with the control or NCoR siRNAs 17 d previously and treated with 300 nM TSA for the last 24 h. (E) Western blot of NCoR and SMRT with the indicated antibodies in SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 17 d previously and treated with TSA during the last 24 h. (F) Western blot of NCoR, ERK, SMRT, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and total H3 in the groups shown in B. (G) Recruitment of H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and HP1γ to the +814/+1056 region of the NCoR gene. ChIP assays were performed in SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 24 d previously. (H) Sequence of the +814/+1056 fragment of the NCoR gene showing putative binding sites for SP1 in red. (I) SP1 recruitment to the NCoR gene in the conditions shown in G. (J) ChIP assays with IgG, H3K9me3, and SP1 antibodies in cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR for 15 d and with TSA during the last 24 h.

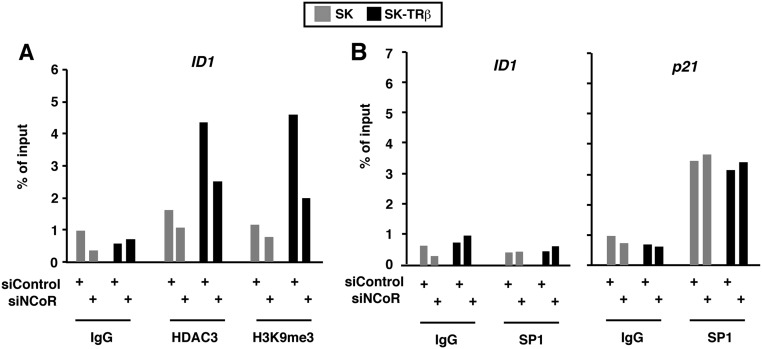

Other posttranslational histone modifications such as methylation of H3K9 have a crucial influence on chromatin structure and transcriptional repression. H3K9 trimethylation enables binding of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), which facilitates local heterochromatinization (35). Furthermore, H3K27 methylation, another repressive marker, can synergize with HDAC complexes and H3K9 methylation to silence chromatin (36). Interestingly, we found that NCoR depletion induced a global cellular increase in the levels of H3K9me3 and that H3K27me3 levels also were induced, whereas the total levels of H3 were unaltered in the absence of the corepressor (Fig. 7F). ChIP assays also showed a strong increase in the abundance of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 at the NCoR promoter associated with NCoR knockdown, and under these conditions HP1γ was recruited also (Fig. 7G), thus creating a stably silenced chromatin state. Examination of the NCoR sequences used in the ChIP assays showed the existence of three putative SP1-binding motifs (Fig. 7H). One of the mechanisms by which silencing was sustained could involve the inhibition of recruitment of key transcription factors in this repressive chromatin structure. In agreement with this hypothesis, SP1 bound the NCoR promoter in cells transfected with siControl, but it was excluded in NCoR-depleted cells (Fig. 7I). Therefore, transcriptional repression of the NCoR gene in cells transfected with siNCoR appears to be associated with heterochromatinization and SP1 removal from the promoter. This action was specific for the NCoR gene, because HDAC3 recruitment to the ID1 promoter did not increase in cells depleted of NCoR and was even clearly reduced in SK-TRβ cells, as expected for an NCoR target gene. The same results were obtained with H3K9me3 levels, which were reduced in the cells transfected with siNCoR despite the higher total levels of this histone modification (Fig. S8A). In addition, SP1 did not bind to the ID1 promoter, but its association to the p21 promoter, a well-known target gene of this transcription factor, was not affected by NCoR knockdown (Fig. S8B).

Fig. S8.

Changes seen in the NCoR gene promoter after NCoR depletion are not found in other genes. (A) ChIP assays with the −271/+13 region of the ID1 gene in SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 24 d previously. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibodies against HDAC3 and H3K9me3 or with control IgGs. (B) ChIP assays in the same experimental groups using antibodies against SP1 and amplifying the ID1 (−271/+13) and p21 (−192/+72) promoter fragments. In both panels data are expressed relative to the values obtained in SK cells transfected with the control siRNA and were obtained from two independent experiments with less than 20% variation.

To clarify why TSA invokes a strong response in NCoR expression when other repressive epigenetic marks are also altered, we tested the possibility that the HDAC inhibitor also could influence H3K9me3 abundance at the NCoR regulatory region. ChIP assays showed the expected increase in H3K9 methylation after NCoR silencing, but this increase was totally inhibited in TSA-treated cells, coinciding with NCoR derepression. As expected, heterochromatinization was reversed under these conditions because SP1 was able to associate with the NCoR gene (Fig. 7J).

Discussion

This work shows the important tumor-suppressive role of the corepressor NCoR. NCoR inhibits the invasive ability of malignant cells, and knockdown of the corepressor enhances their ability to grow as invasive tumors, to pass into the circulation, and to form metastases, agreeing with the circumstantial evidence of reduced NCoR expression in human tumors, in some cases associated with truncating mutations and homozygous deletions of the NCoR gene (19, 21, 22), providing an explanation for these findings and defining NCoR as a potential target for cancer therapy.

Increasing evidence indicates that epigenetic alterations involving an altered pattern of histone modifications lead to the misregulation of gene expression and can contribute to cancer development (37, 38). Our results show that the tumor-suppressive effects of NCoR are linked to the silencing of genes involved in metastatic spreading, whose expression has been associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients (39–44). NCoR, together with HDAC3, the main enzyme responsible for the repressive activity of NCoR (45), binds to the promoters of several prometastatic genes, thereby inhibiting histone acetylation and repressing their transcription.

An unexpected observation was that transient NCoR silencing with siRNA led to very long-lasting inhibition of NCoR expression. This inhibition was observed both in cultured cells and in the tumors and metastatic lesions and was accompanied by derepression of prometastatic genes. Similar to these results, a single episode of RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans can induce inheritable reduced transcription of some genes, which can be relieved in the presence of TSA (46). Furthermore, some cases of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance seem to involve inherited histone methylation patterns (38), and in the nematode long-term silencing is associated with increased H3K9me3 levels that can be passed through generations without being lost (18).

Stable NCoR silencing after siRNA occurs via a transcriptional mechanism dependent on changes in chromatin structure. Despite the presence of a regulatory CpG island within the NCoR gene, DNA methylation of this region was not involved in silencing, suggesting that this is not the main mechanism responsible for NCoR autoregulation. Next, we investigated histone methylation and found that increased abundance of H3K9me3, one of the best markers of heterochromatin, and to a lesser extent of H3K27me3, another repressive marker, were linked to repression. Remarkably, siRNA-mediated suppression of NCoR increased the global levels of H3K9me3, suggesting that chromatin structure is globally altered in the absence of the corepressor. However, we did not find an increase in H3K9me3 association with other genes. It presently is unclear how the gene-target specificity is achieved, but it could involve the assembly of different sets of cofactors and histone-modifying enzymes (1). H3K9 methylation facilitates the recruitment of HP1 (47, 48), allowing local heterochromatinization (49), and accordingly HP1γ also was recruited to the silenced NCoR gene. In addition to the increased abundance of transcriptional repressive methylation markers, siRNA depletion of NCoR strongly increased HDAC3 association with the NCoR gene. This paradoxical recruitment in the absence of NCoR was caused by SMRT recruitment. The existence of cross-talk between posttranslational histone modifications is well known (37), and we found that inhibiting HDAC activity with TSA also inhibits H3K9me3 abundance at the NCoR gene. Thus, both histone deacetylation and methylation appear to play important roles in the establishment of a local repressive state that leads to long-lasting inhibition of NCoR gene transcription, presumably by providing a heterochromatic environment that could prevent sequence-specific transcription factor binding. Indeed, under these conditions SP1 could not bind to the promoter, in agreement with findings indicating that occlusion of SP1 binding is associated with increased H3K9me3 (50). Interestingly, NCoR depletion could represent an important mechanism for tumor progression when no NCoR mutations are present. A cellular change resulting in a reduction in NCoR levels at a given point in time could be propagated through many cell generations, allowing the cancer cell to proliferate and to become invasive.

Our results show that NCoR levels are increased in cancer cell lines, as well as in nontumoral hepatocytes, after TRβ expression. Surprisingly, this increase occurred in a ligand-independent manner. It is possible that the unliganded receptor could have constitutive effects on NCoR expression when expressed at high concentrations or that residual amounts of thyroid hormones in the serum could be sufficient for maximal stimulation under these conditions. NCoR induction appears to play a crucial role in the antitumorigenic and antimetastatic actions of the receptor (24), because these actions were reversed almost completely upon NCoR silencing. We also have shown that, in contrast with the native receptor, TRβ mutants unable to bind the corepressor cannot antagonize Ras-mediated transformation and tumorigenesis (26), reinforcing the idea that NCoR is an essential mediator of the tumor-suppressive actions of TRβ. TRβ-mediated up-regulation of NCoR could extend the scope of genes that are influenced by the receptor, because the corepressor has been shown to repress transcription through other nuclear receptors and numerous transcription factors with a role in cancer progression (1, 12). Therefore, repression of prometastatic gene expression could be a consequence of NCoR interaction with this receptor or, more likely, with other transcription factors that associate with their promoters. The findings that the effects of TRβ are largely ligand independent and that NCoR binds to the promoters of prometastatic genes in parental SK cells that express very low levels of TR support the hypothesis that NCoR could be recruited to these promoters by other DNA-binding proteins. The increased levels of NCoR would be sufficient to account for the T3-independent action of TRβ in prometastatic gene expression. This action would be particularly important for transcription factors preferentially interacting with NCoR rather than SMRT, because TRβ did not significantly regulate SMRT. Furthermore, SMRT depletion affected neither metastatic gene expression nor the invasive capacity of SK or MDA cancer cells, suggesting the specific role of NCoR in these processes.

Our data confirm that NCoR mRNA levels are reduced in human HCC, in agreement with the finding that Hdac3 deletion in mice causes the appearance of these tumors (22). Furthermore, NCoR expression was decreased in the cirrhotic peritumoral tissue, which is considered to be precancerous, further supporting a tumor-suppressive role for NCoR in human HCC. On the other hand, hypothyroidism has been considered to be a risk factor for the development of HCC in humans (51, 52), and TRβ down-regulation has been reported recently to be an early event in human and rat HCC development (29). Interestingly, we found that TRβ transcripts not only were significantly reduced in the tumors compared with normal tissues but also correlated positively with the levels of the corepressor. A strong correlation between TRβ and NCoR expression also was found in human breast tumors and, interestingly, both genes were markedly down-regulated in ER− tumors as compared with ER+ tumors that have a better prognosis. Thus, our results support the possibility that the receptor is an upstream stimulator of NCoR gene expression and suggest that NCoR and TRβ could be considered potential biomarkers for some types of human cancers.

Although the mechanisms underlying the role of chromatin regulation in oncogenesis are complex and remain to be defined in a cellular context-dependent manner, our data hold the potential of defining the epigenetic signatures associated with NCoR expression in tumors for potential use as diagnostic or prognostic markers. Elucidating the link between epigenetic mechanisms connecting NCoR loss and tumor progression should prompt the development of more efficient therapeutic strategies as well as facilitate a better understanding of tumor biology.

Materials and Methods

Extended materials and methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Animal and human studies were approved by the Ethics Committees of the Ramón and Cajal Hospital and the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Informed consent was obtained for the study. NCoR and SMRT were knocked down in parental and TRβ-expressing cells with specific siRNA SMART pools from Dharmacon. Experimental procedures for transfections, luciferase reporter assays, Western blot, mRNA determination by real-time PCR, and ChIP assays have been published previously and are described together with the antibodies and primers used in SI Materials and Methods. Clinical and pathological characteristics of HCC and breast cancer samples are given in Tables S1 and S2. Invasion assays in vitro in Transwell plates containing Matrigel and extravasation assays to the lung in vivo were performed as previously described (24, 25). Metastasis formation in the lungs was determined 30 d after inoculation of tumor cells into the tail vein of nude mice, and tumor formation was followed for 6 wk after inoculation into the flanks or the mammary pad. Lung areas affected by metastasis were dissected by laser-capture microdissection, and RNA was extracted. Histology and immunohistochemistry were performed by standard procedures. Significance of ANOVA posttest or the Student t test among the experimental groups indicated in the figures is shown as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Table S1.

Clinical and pathological data of HCCs

| Patient age, y | Sex | Pathological diagnosis |

| 58 | Female | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis with cholestasis and siderosis. |

| 59 | Male | Poorly differentiated HCC with portal venule embolizations. Active septal incomplete cirrhosis. |

| 58 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis. |

| 63 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis. |

| 64 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis. |

| 57 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis. |

| 51 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis with siderosis. |

| 53 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis with slight inflammation (compatible with viral C etiology). |

| 63 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis with moderate steatohepatitis. |

| 67 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis. |

| 51 | Male | Moderately differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis compatible with viral C etiology. |

| 45 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis compatible with viral C etiology. |

| 53 | Male | Moderately differentiated HCC with vascular permeation images. Mixed inactive cirrhosis, compatible with viral C etiology. |

| 64 | Female | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis. |

| 49 | Male | Well-differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis with siderosis. |

| 58 | Male | Poorly differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis. |

| 62 | Female | Moderately differentiated HCC. Mixed inactive cirrhosis compatible with viral C etiology. |

| 59 | Male | Moderately differentiated HCC. Mixed cirrhosis compatible with viral C etiology. |

Table S2.

Clinical and pathological data of breast tumors

| Grade | ER status | Type |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 1 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 1 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Negative | Mucinous infiltrating carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 2 | Positive | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

| 3 | Negative | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma |

SI Materials and Methods

Study Approval.

Animal experiments were carried out in the animal facility of the Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas in compliance with European Community Law (86/609/EEC) and Spanish law (R.D. 1201/2005), with approval of the Ethics Committee of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Mice were housed in pathogen-free conditions in a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle with water and normal diet food available ad libitum. Animals always were distributed randomly among the experimental groups. The use of human HCC and normal liver paraffin samples and breast cancer RNA samples (Tables S1 and S2) was performed in accordance with standard ethical procedures of the Spanish regulations (Ley Orgánica de Investigación Biomédica, July 14, 2007) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigations of the Ramón and Cajal Hospital and the Ethics Committee of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Breast cancer samples were obtained from the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio and Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla Biobank (Andalusian Public Health System Biobank and Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Red de Biobancos PT13/0010/0056).

Cell Lines.

SK-hep1 and MDA MB 468 cells transduced with an empty vector (SK and MDA cells, respectively), and cells expressing human TRβ1 in a stable manner (SK-TRβ and MDA-TRβ cells) have been described previously (24). Parental and TRβ-expressing HepG2 and HH4 hepatocytes also have been described (25). Cells were mycoplasma free and were authenticated with the StemElite System (Promega), frozen, and always used within 1–3 mo after resuscitation. Cells were maintained in medium supplemented with 10% FBS treated with AG-X-8 resin.

siRNA Knockdown.

Validated siRNA SMART pools targeted toward human NCoR (M-058556) and SMRT (M-045364) were purchased from Dharmacon. Cells were transfected with 33 ng of NCoR siRNA (siNCoR), SMRT siRNA (siSMRT), or with nonspecific control pool (siControl) (M-001210) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were used 72 h after transfection, or as indicated, in the presence or absence of 5 nM T3.

Transfection and Reporter Assays.

Cells were transiently transfected with 300 ng of reporter plasmids and 30 ng of pRL-TK-Renilla (Promega) as a normalizer control, using Lipofectamine 2000. Reporter constructs with fragments of the COX2, MMP9, and ID1 promoters were described previously (33, 53, 54). When appropriate, the reporter was cotransfected with 33 ng of siRNAs, 200 ng of an expression vector for NCoR (55), or a noncoding vector. Luciferase activity was measured in untreated cells and in cells treated with 5 nM T3 for 36 h using the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Each experiment was performed in triplicate and normally was repeated at least three times.

Western Blotting.

Proteins from cell lysates (80 µg) were separated in SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran Whatman; Perkin-Elmer) that were blocked for 2 h at room temperature with 4% BSA or nonfat milk. Incubation with primary antibodies was performed overnight at 4 °C and with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were visualized with ECL (Amersham). The antibodies used are listed below. To verify the specificity of NCoR changes, two different NCoR and SMRT antibodies were used. The NCoR antibody A301-145A (Bethyl) was demonstrated not to show cross-reactivity with SMRT by Vella et al. (56).

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol (Sigma) and from tumors and from 30 deparaffinized sections using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). mRNA levels were analyzed in technical triplicates by quantitative RT- PCR, following the specifications of SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Data analysis was done using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method, and data were corrected with GAPDH mRNA levels. Primers are listed below.

ChIP.

Cells were plated in 150-mm dishes, fixed and lysed following the specifications of the Upstate kit (catalog no. 17-295), and sonicated in a Bioruptor UCD-200TM (Diagenode). In each immunoprecipitation 2–3 × 106 cells and the amount of antibodies listed below were used. DNA was purified, precipitated, and used for real-time PCR amplification of the regions of the genes listed below. Data are expressed relative to the values obtained in parental SK cells immunoprecipitated with control IgGs and were obtained in three independent experiments.

Invasion Assays.

Cells that had been transfected with siRNAs 56 h previously were inoculated into the upper chamber of Transwell plates containing Matrigel as previously described (24). Sixteen hours later cells that passed through the filter were stained and scored.

Extravasation Assays in Nude Mice.

Exponentially growing cells were transfected with siControl or siNCoR and 48 h later were labeled with 2.5 µCi 125I-deoxyuridine as described (24). Groups of 10 immunodeficient female mice (athymic nude-Nu; 8–10 wk old) obtained from Harlan were injected via the tail vein with 5 × 105 cells suspended in 100 µL of PBS. Animals were killed 9 h after injection, and the radioactivity incorporated into the lungs was determined (24). Alternatively, lung extravasation was quantitated 8 h after inoculation of 3 × 106 cells by real-time PCR of human APO Alu sequences located in human chromosome 11, as described (25). Results are expressed as the percent of amplified human DNA with respect to the amount of total DNA injected.

Metastasis Assays.

For the formation of experimental metastases in lung, 1 × 106 cells were injected into the lateral tail vein of nude mice. Animals (six per group) were killed 30 d after the injection of SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 72 h before injection.

Tumor Xenografts.

Groups of six nude mice were used for xenografting studies. SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR (1 × 106 cells in 100 µL PBS) 72 h before injection were injected s.c. into each flank (12 tumors per group). MDA and MDA-TRβ cells (2 × 106 cells in 100 µL PBS) were inoculated orthotopically into the fat mammary pad (eight tumors). Primary tumor outgrowth was monitored twice a week, and tumor volume was calculated as previously described (24). Animals were killed 42 d after inoculation with SK cells and 33 d after inoculation with MDA cells.

Laser-Capture Microdissection.

Lung sections (4 μm) were cut in PALM MembraneSlides 1.0 PEN (415101-4401)-0000 to be deparaffinized and stained with H&E. Lung areas affected by metastasis were dissected with an Olympus IX71-PALM Microlaser equipped with a 325-nm UV-A laser, objective U PlanFl 20×/0.50-thickness glass ring, catapulted, and captured in the cap of an Eppendorf flask with 20 μL buffer [1 mM EDTA (pH 8), 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 0.5% Tween20, and 2 mg/mL proteinase K]. Samples were digested with proteinase K for 16 h at 55 °C, and total RNA was extracted.

Histology.

Samples were fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Deparaffinized tissue sections were stained with H&E or Masson’s trichrome using standard procedures. Images were obtained using a high-resolution Leica DC200 digital camera mounted on an Olympus DMLB microscope.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry of Ki67 or NCoR with antibody ab24552 was performed on 4-µm deparaffinized and rehydrated sections. Antigen retrieval was carried out with citrate buffer, and endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited with 3% H2O2. Samples were blocked and incubated overnight with the antibody, and signal was amplified with the ABC Kit (Vectastain). Slides were revealed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (Vector), counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted with DePeX (Serva). Immunohistochemistry with NCoR antibody sc8994 was performed on 4-µM-thick slides of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks, on a Bond III Leica Automated stainer. NCoR antibody was diluted 1/30, and the Bond Polymer Refine Detection Kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantifications of histology and immunohistochemistry were performed by an examiner blinded to the experimental group of the mice.

Tumor Explants.

Explants were prepared from tumors under sterile conditions 14 d after inoculation of SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl or siNCoR 72 h before inoculation. Explants from four tumors per experimental group were maintained in DMEM:HAMS (1:1) with 10% FBS treated with AG1-X8 resin. mRNA levels were determined after 7 d in culture.

DNA Methylation Assays.

Genomic DNA isolation from SK and SK-TRβ cells that had been transfected with siControl and siNCoR 17 d previously was performed according to a standard phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction protocol after proteinase K digestion. DNA (500 ng) was bisulfite converted with the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (D5006; Zymo Research) following the manufacturer’s advice. Two DNA fragments contained within the CpG island located between nucleotides −687 and +1557 with respect to the first exon of the NCoR gene were PCR amplified from bisulfite-modified DNA and normal DNA. The PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel alongside a molecular weight marker, was cut out and purified by the QIAquick MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and then sequenced on an ABI 3130 sequencer; direct sequencing was performed. We prefer direct sequencing, as performed here, to subcloning a mixed population of alleles to avoid potential cloning efficiency bias and artifact. Alternatively, after PCR amplification of three regions of the NCoR CpG island using the primers listed below, bisulfite pyrosequencing was performed with the PyroMark Q24 reagents, equipment, and software (Qiagen) and the Vacuum Prep Tool (Biotage), following the manufacturers’ instructions. The PyroMark Assay Design tool (v. 2.0.01.15) was used to obtain pyrosequencing oligonucleotides.

Statistics.

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check a normal distribution, and the Levene test was used to assess the equality of variances. Statistical significance of data was determined by applying a two-tailed Student t test or ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test for experiments with more than two experimental groups. P values <0.05 were considered significant. The significance of ANOVA posttest or the Student t test in the experimental groups indicated in the figures is shown as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Linear regressions were calculated with SPSS software. No previous calculations were used to determine sample size, which was chosen based on usual procedures in the field. Results shown are means ± SD or means ± SEM, as specified.

Antibodies and Primers Used in This Study.

Antibodies used and the dilution for each use

| Antibody | Dilution | Use | Provider and catalog no. |

| H3K9me3 | 1 µg | ChIP | Millipore, 07-442 |

| Anti-trimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) | 1:2,000 | Western blot | |

| H3K27me3 | 1 μg | ChIP | Millipore, 07-449 |

| Anti-trimethyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) | 1:2,000 | Western blot | |

| H3Ac | 1 µg | ChIP | Upstate, 06-599 |

| H3 | 1:2,000 | Western blot | Abcam, ab1791 |

| Erk2 | 1:5,000 | Western blot | Santa Cruz, sc-154 |

| HDAC3 | 1 µg | ChIP | Abcam, 7030 |

| 1:2,000 | Western blot | ||

| Ki67 | 1:200 | Immunohistochemistry (IHH) | DakoCytomation, M7240 |

| Laminß | 1:1,000 | Western blot | Santa Cruz, sc-6216 |

| NCoR | 1:1,000 | Western blot | Bethyl A, 301-145A |

| NCoR | 5 µg | ChIP | Santa Cruz, sc-8994 |

| 1:500 | Western blot | ||

| 1:30 | IHH | ||

| NCoR | 1:20 | IHH | Abcam, ab24552 |

| SMRT | 1 µg | ChIP | Upstate, 06-891 |

| 1:1,000 | Western blot | ||

| SMRT | 1:1,000 | Western blot | Affinity Bioreagents, PA1-843 |

| TRβ | 5 µg | ChIP | Santa Cruz, sc-772 |

| 1:500 | Western blot | ||

| SP1 | 1 µg | ChIP | Santa Cruz, sc-59 |

| 1:2,000 | Western blot | ||

| HP1γ | 1 μg | ChIP | Santa Cruz, sc-365085 |

Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR

| Transcript | Forward | Reverse |

| CXR4 | ATCTTTGCCAACGTCAGT | TCACACCCTTGCTTGATG |

| C-MET | GAGCCAAGTCCTTTCAT | ATCGAATGCAATGGATGAT |

| CCR6 | CCATTCTGGGCAGTGAGTCA | AGCAGCATCCCGCAGTTAA |

| CCR1 | CTCTTCCTGTTCACGCTTCC | GCCTGAAACAGCTTCCACTC |

| CCR7 | GGTGGGCGGCTCTACTAAAA | GCACAGAGTTGGACACGACT |

| COX2 | GCA AAT CCT TGC TGT TCC | GGAGGAAGG GCT CTA GTA |

| ID1 | AGAAGCACCAAACGTGACCATT | TCCGCACACCTACTAGTCACCCA |

| MMP9 | AAGGATGGTCTACTGGCAC | AGAGATTCTCACTGGGGC |

| MMP2 | TTGATCGTTCTCGTCGCCAA | CTCCGCCGACATCTTCAGTT |

| NCoR | GCTGCAGGAGAGGTTTATC | TGTCACCTCAGCCAGCATAG |

| SMRT | TGTCACCTCAGCCAG CATAG | CGCCGTAAGTAGTCCTCCTG |

| TRβ | CCAGAAGACATTGGACAAGCACC | TGCCATTTCCCCATTCAAGG |

| GAPDH | ACAGTCCATGCCATCACTGCC | GCCTGCTTCACCCCTTCTTG |

| Dio1 | ACACCATGCAGAACCAGAG | AGAACAGCACGAACTTCCTC |

Primers used for ChIP

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| COX2 −274/ +19 | CTGGGTTTCCGATTTTCTCA | GGGTAGGCTTTGCTGTCTGA |

| MMP9 −376 /−87 | GCAGTTTGCAAAACCCTACC | GAGGGCAGAGGTGTCTGACT |

| ID1 −271/+13 | GACCCACCCTTGGCTGTTCT | GCGACTGGCTGAAACAGAAT |

| NCOR +814/+1056 | GTGAGTAGGTTTTGG | GGACAACCCATTCTTCCTCC |

| ID1 −1006/−746 | CGCCAGCCTGACAGTCCGTC | GGCTGCATTCGATTCCACC |

| ID1 −1817/−1609 | CCACTGCGCCCGGCCCCCTG | GCCGGGCATGGTAGCGTTCG |

| ID1 −2568/−2382 | GGTTTGGTTTTCCTGGTTTCC | CTGTGCTCACCAGTGGAGG |

| p21 −192/+72 | GGCTGGCCTGCTGGAACTC | GCAGCTGCTCACACCTCAGC |

Primers used for bisulfite sequencing

| Region | Forward | Reverse |

| Primer region 1 | GTYGGGTTTGGTTTTTTTAAAGGA | CTCTTCATATCTCCTCTAAACCT |

| Degenerated primer: Y = C+T | ||

| Primer region 2 | GGGGAGGGAGAGGGGTTGA | TTCCTCCAAACTCCATAAACCT |

Primers used for bisulfite pyrosequencing

| Region 1 | |

| Forward: 5′-TTGTAAGTAATTTAAGGTTAAGGAGTAA-3′ | |

| Reverse: 5′-ACCAAACCCTCACTAAAATACTA-3′ | |

| Sequencing: 5′-GTAATTTAAGGTTAAGGAGTAATA-3′ | |

| Region 2 | |

| Forward: 5′-GTTGTTAGGTTTAGAGGAGATATGA-3′ | |

| Reverse: 5′-CATCTTAACTCAACCCCTCT-3′ | |

| Sequencing: 5′-GGGAGTTGGTTTTTTAATT-3′ | |

| Region 3 | |

| Forward: 5′-ATGGAGTTTGGAGGAAGAAT-3′ | |

| Reverse: 5′-ACCCCTTCTACACTTCCAA-3′ | |

| Sequencing: 5′-AGTTTGGAGGAAGAATG-3′ |

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Fabra, M. Fresno, B. Chandrasekar, and M. Privalsky for plasmids, the Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas services for support, and C. Sanchez-Palomo for technical help. We thank the donors and the Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio and Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla Biobank (Andalusian Public Health System Biobank and Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Red de Biobancos PT13/0010/0056). This work was supported by Grants BFU2011-28058 and BFU2014-53610-P from Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad; Grant S2011/BMD-2328 from the Comunidad de Madrid; Grant RD12/0036/0030 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (to A.A.); Grants PI080971 and RD12 0036/0064 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (to J.P.); and Grant PI12/00386 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (to I.I.d.C.). O.A.M.-I. is supported by an Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer contract. The cost of this publication was paid in part by funds from the European Fund for Economic and Regional Development.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1520469113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Perissi V, Jepsen K, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Deconstructing repression: Evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(2):109–123. doi: 10.1038/nrg2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen JD, Evans RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995;377(6548):454–457. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hörlein AJ, et al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature. 1995;377(6548):397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perissi V, Aggarwal A, Glass CK, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG. A corepressor/coactivator exchange complex required for transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors and other regulated transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116(4):511–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codina A, et al. Structural insights into the interaction and activation of histone deacetylase 3 by nuclear receptor corepressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(17):6009–6014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500299102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon HG, et al. Purification and functional characterization of the human N-CoR complex: The roles of HDAC3, TBL1 and TBLR1. EMBO J. 2003;22(6):1336–1346. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Privalsky ML. The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:315–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.155556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman HB, Yu J, Alenghat T, Ishizuka T, Lazar MA. The histone-binding code of nuclear receptor co-repressors matches the substrate specificity of histone deacetylase 3. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(5):445–451. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen YD, et al. The histone deacetylase-3 complex contains nuclear receptor corepressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(13):7202–7207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astapova I, et al. The nuclear corepressor, NCoR, regulates thyroid hormone action in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(49):19544–19549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804604105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishizuka T, Lazar MA. The N-CoR/histone deacetylase 3 complex is required for repression by thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(15):5122–5131. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5122-5131.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mottis A, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J. Emerging roles of the corepressors NCoR1 and SMRT in homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):819–835. doi: 10.1101/gad.214023.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurebayashi J, et al. Expression levels of estrogen receptor-alpha, estrogen receptor-beta, coactivators, and corepressors in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(2):512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciriello G, et al. The molecular diversity of Luminal A breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(3):409–420. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2699-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green AR, et al. The prognostic significance of steroid receptor co-regulators in breast cancer: Co-repressor NCOR2/SMRT is an independent indicator of poor outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(3):427–437. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9737-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girault I, et al. Expression analysis of estrogen receptor alpha coregulators in breast carcinoma: Evidence that NCOR1 expression is predictive of the response to tamoxifen. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(4):1259–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490(7418):61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerji S, et al. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature. 2012;486(7403):405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephens PJ, et al. Oslo Breast Cancer Consortium (OSBREAC) The landscape of cancer genes and mutational processes in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;486(7403):400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature11017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu XR, et al. Insight into hepatocellular carcinogenesis at transcriptome level by comparing gene expression profiles of hepatocellular carcinoma with those of corresponding noncancerous liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15089–15094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241522398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guichard C, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):694–698. doi: 10.1038/ng.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhaskara S, et al. Hdac3 is essential for the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aranda A, Martínez-Iglesias O, Ruiz-Llorente L, García-Carpizo V, Zambrano A. Thyroid receptor: Roles in cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(7):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez-Iglesias O, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor beta1 acts as a potent suppressor of tumor invasiveness and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2):501–509. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz-Llorente L, Ardila-González S, Fanjul LF, Martínez-Iglesias O, Aranda A. microRNAs 424 and 503 are mediators of the anti-proliferative and anti-invasive action of the thyroid hormone receptor beta. Oncotarget. 2014;5(10):2918–2933. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.García-Silva S, Martínez-Iglesias O, Ruiz-Llorente L, Aranda A. Thyroid hormone receptor β1 domains responsible for the antagonism with the ras oncogene: Role of corepressors. Oncogene. 2011;30(7):854–864. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledda-Columbano GM, Perra A, Loi R, Shinozuka H, Columbano A. Cell proliferation induced by triiodothyronine in rat liver is associated with nodule regression and reduction of hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2000;60(3):603–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perra A, Kowalik MA, Pibiri M, Ledda-Columbano GM, Columbano A. Thyroid hormone receptor ligands induce regression of rat preneoplastic liver lesions causing their reversion to a differentiated phenotype. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/hep.22750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frau C, et al. Local hypothyroidism favors the progression of preneoplastic lesions to hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):249–259. doi: 10.1002/hep.27399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan IH, Privalsky ML. Thyroid hormone receptor mutants implicated in human hepatocellular carcinoma display an altered target gene repertoire. Oncogene. 2009;28(47):4162–4174. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin KH, Wu YH, Chen SL. Impaired interaction of mutant thyroid hormone receptors associated with human hepatocellular carcinoma with transcriptional coregulators. Endocrinology. 2001;142(2):653–662. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.2.7927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eun JR, et al. Hepatoma SK Hep-1 cells exhibit characteristics of oncogenic mesenchymal stem cells with highly metastatic capacity. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordà M, et al. Id-1 is induced in MDCK epithelial cells by activated Erk/MAPK pathway in response to expression of the Snail and E47 transcription factors. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(11):2389–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng XH, Lin X, Derynck R. Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with Sp1 to induce p15(Ink4B) transcription in response to TGF-beta. EMBO J. 2000;19(19):5178–5193. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V. A new world of Polycombs: Unexpected partnerships and emerging functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(12):853–864. doi: 10.1038/nrg3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):139–170. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: A dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(5):343–357. doi: 10.1038/nrg3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang F, Geng XP. Chemokines and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(15):1832–1836. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i15.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lengyel E, et al. C-Met overexpression in node-positive breast cancer identifies patients with poor clinical outcome independent of Her2/neu. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(4):678–682. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costamagna E, García B, Santisteban P. The functional interaction between the paired domain transcription factor Pax8 and Smad3 is involved in transforming growth factor-beta repression of the sodium/iodide symporter gene. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(5):3439–3446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minn AJ, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436(7050):518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schimanski CC, et al. Chemokine receptor CCR7 enhances intrahepatic and lymphatic dissemination of human hepatocellular cancer. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(1):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang X, et al. Essential contribution of a chemokine, CCL3, and its receptor, CCR1, to hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(8):1869–1876. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.You SH, et al. Nuclear receptor co-repressors are required for the histone-deacetylase activity of HDAC3 in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(2):182–187. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vastenhouw NL, et al. Gene expression: Long-term gene silencing by RNAi. Nature. 2006;442(7105):882. doi: 10.1038/442882a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410(6824):116–120. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bannister AJ, et al. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410(6824):120–124. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groner AC, et al. KRAB-zinc finger proteins and KAP1 can mediate long-range transcriptional repression through heterochromatin spreading. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(3):e1000869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strunnikova M, et al. Chromatin inactivation precedes de novo DNA methylation during the progressive epigenetic silencing of the RASSF1A promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(10):3923–3933. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.3923-3933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassan MM, et al. Association between hypothyroidism and hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-control study in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;49(5):1563–1570. doi: 10.1002/hep.22793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reddy A, et al. Hypothyroidism: A possible risk factor for liver cancer in patients with no known underlying cause of liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corral RS, Iñiguez MA, Duque J, López-Pérez R, Fresno M. Bombesin induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression through the activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells and enhances cell migration in Caco-2 colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(7):958–969. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chandrasekar B, et al. Interleukin-18-induced human coronary artery smooth muscle cell migration is dependent on NF-kappaB- and AP-1-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and is inhibited by atorvastatin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(22):15099–15109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mengeling BJ, Phan TQ, Goodson ML, Privalsky ML. Aberrant corepressor interactions implicated in PML-RAR(alpha) and PLZF-RAR(alpha) leukemogenesis reflect an altered recruitment and release of specific NCoR and SMRT splice variants. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(6):4236–4247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vella KR, et al. Thyroid hormone signaling in vivo requires a balance between coactivators and corepressors. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(9):1564–1575. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00129-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]