Significance

The mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) belongs to the emerging class of higher-order signaling machines that adopt a filamentous state on activation and propagate in a prion-like manner. Structures of helical filaments are challenging due to their size and variable symmetry parameters, which are notoriously difficult to obtain, but are a prerequisite for structure determination by electron microscopy and by solid-state NMR. Here we describe a strategy for their efficient de novo determination by a grid-search approach based exclusively on solid-state NMR data. In combination with classical NMR structure calculation, we could determine the atomic resolution structure of fully functional filaments formed by the globular caspase activation and recruitment domain of MAVS. A careful validation highlights the general applicability of this approach.

Keywords: solid-state NMR, protein structure, grid search, MAVS, innate immunity

Abstract

The controlled formation of filamentous protein complexes plays a crucial role in many biological systems and represents an emerging paradigm in signal transduction. The mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) is a central signal transduction hub in innate immunity that is activated by a receptor-induced conversion into helical superstructures (filaments) assembled from its globular caspase activation and recruitment domain. Solid-state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy has become one of the most powerful techniques for atomic resolution structures of protein fibrils. However, for helical filaments, the determination of the correct symmetry parameters has remained a significant hurdle for any structural technique and could thus far not be precisely derived from ssNMR data. Here, we solved the atomic resolution structure of helical MAVSCARD filaments exclusively from ssNMR data. We present a generally applicable approach that systematically explores the helical symmetry space by efficient modeling of the helical structure restrained by interprotomer ssNMR distance restraints. Together with classical automated NMR structure calculation, this allowed us to faithfully determine the symmetry that defines the entire assembly. To validate our structure, we probed the protomer arrangement by solvent paramagnetic resonance enhancement, analysis of chemical shift differences relative to the solution NMR structure of the monomer, and mutagenesis. We provide detailed information on the atomic contacts that determine filament stability and describe mechanistic details on the formation of signaling-competent MAVS filaments from inactive monomers.

Large higher-order protein assemblies play pivotal roles in diverse biological systems. Most of these assemblies, such as cytoskeleton filaments, fibrils, flagella, viral capsids, and the newly emerging cellular signaling machineries (1), are composed of repetitive and symmetrically arranged building blocks, the protomers. Typically, their sizes and often filamentous natures render them refractory to X-ray crystallography and solution NMR. Electron microscopy (EM) studies have provided valuable structural information. However, thus far, only few cryo-EM structures could be obtained with sufficient resolution to decipher fine details of the interprotomer contacts (2, 3). In addition, ambiguities in the determination of the helical symmetries have occasionally given rise to contradictory structural models (4–8). In the last decade, magic angle spinning solid-state NMR (ssNMR) has become a powerful technique to determine atomic resolution structures of protein filaments, in particular of amyloid fibrils (9–14). ssNMR has been successfully combined with cryo-EM data and computational approaches to determine the helical filament structure of the type III secretion needle (15, 16), and ssNMR distance restraints allowed to further refine the interprotomer contacts (16, 17). In general, helical filaments are particularly challenging because of restraint ambiguities inherent to homo-oligomeric assemblies, the large, and varying, number of interacting protomers and the ensuing size of the atomic complex to be modeled, and because the symmetry is defined by numerous parameters, most importantly the rotational twist (around the helical axis) and the translational rise (along the axis) between two subunits, the radius and the number of strands defining the helical assembly (18). Without prior knowledge of these parameters from complementary structural techniques, the conformational space to be explored can easily become intractable.

In innate immunity, the detection of viral RNA by retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I)–like receptors converts the inactive, monomeric form of the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) into high-molecular weight filaments that activate IFN signaling pathways (19). Although the N-terminal caspase recruitment domain (CARD) of MAVS (MAVSCARD) is necessary and sufficient for filament formation, downstream signaling is mediated by the more flexible C-terminal region of MAVS (19). The filaments are propagated in a prion-like manner and can be induced by the tandem CARDs of RIG-I-like receptors or by preformed MAVSCARD filaments (20). CARDs belong to the death domain superfamily of protein–protein interaction domains, which share a common six-helix bundle fold and form homo- and hetero-oligomeric structures with variable symmetry (21). The crystal structure of monomeric MAVSCARD fused to maltose binding protein is available (22), and we have previously presented the sequence-specific secondary structure of this domain in its filamentous form (23). Two competing structural models of MAVSCARD filaments derived from cryo-EM reconstructions were published last year (5, 6).

Here we present a generally applicable strategy to derive the symmetry parameters of helical filaments exclusively from ssNMR-derived data and use this strategy to determine the atomic resolution structure of MAVSCARD filaments. We show that the helical symmetry parameters and handedness can be faithfully derived from interprotomer ssNMR distance restraints. In addition, we used solution NMR, paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE), and mutagenesis to validate our approach and to unravel details of the MAVSCARD assembly mechanism.

Results

Distance Restraints from ssNMR Spectroscopy.

Isotope-labeled WT MAVSCARD filaments were purified under nondenaturing conditions from Escherichia coli. These filaments induced MAVS-mediated IFN stimulation when electroporated into a reporter cell line (Fig. S1 A–F), indicating that they were fully functional and structurally compatible with endogenous full-length MAVS. In homo-oligomeric assemblies, distance restraints observed in uniformly isotope labeled samples may arise either from inter- or intraprotomer contacts. We thus based our structure determination strategy on a set of dilute (9) and mixed isotope-labeled samples (15, 24). To prepare these, we made use of our observation that MAVSCARD filaments could be reversibly disassembled into monomers and reassembled into filaments by changing buffer pH. To confirm that the monomer remained structurally unchanged at low pH, we determined the solution NMR structure of monomeric MAVSCARD at pH 3.0 and compared it with the X-ray structure determined at neutral pH 8.5 (Table S1 and Fig. S1G). We also found no effect on the assembly pattern of the filaments as evidenced by negative stain EM images and 2D 13C-13C proton-driven spin diffusion (PDSD) spectra on uniformly 13C,15N-labeled MAVSCARD filaments before and after reassembly (Fig. S1 H–J). As no evidence has yet been found, by us or others, for smaller stable oligomeric species, we consider a single MAVSCARD molecule as the protomeric unit within the filament.

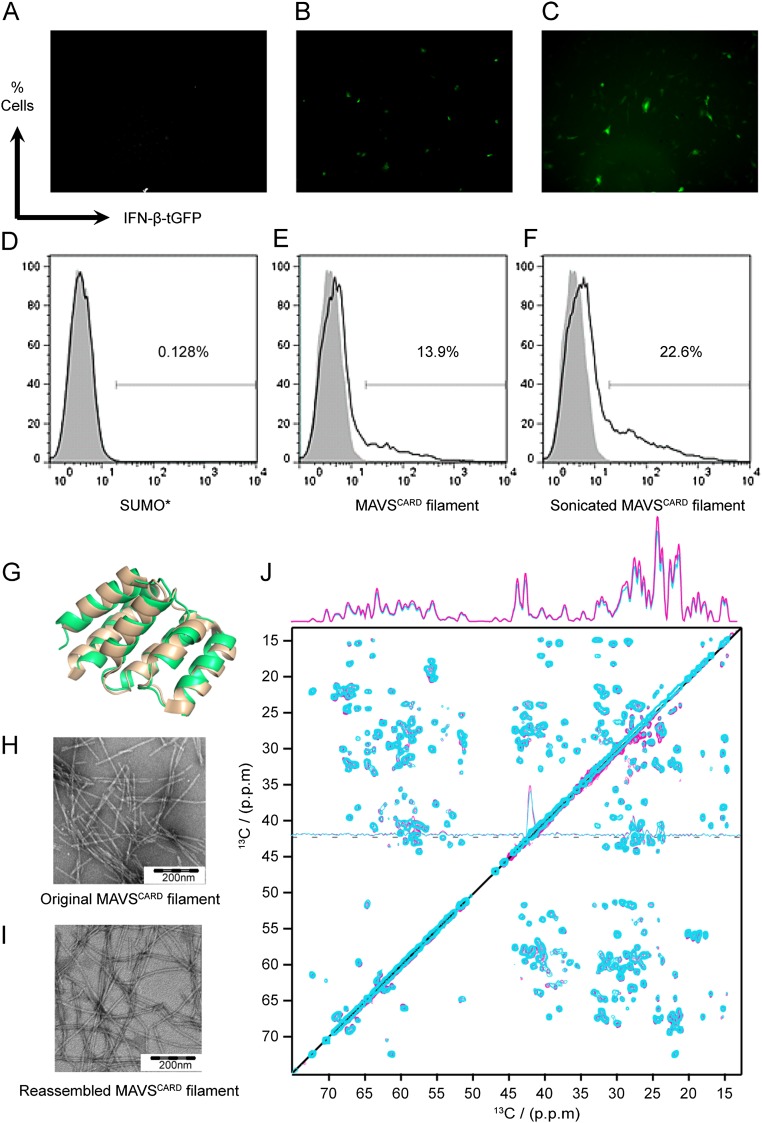

Fig. S1.

Characterization of in vitro-purified MAVSCARD filaments used for ssNMR experiments. (A–C) Fluorescence microscopy of an IFN-β-GFP reporter cell line electroporated with the small ubiquitin-like modifyer (SUMO)*-tag and with MAVSCARD filaments. GFP production is under the control of the IFN-β promotor and thus reports on the activation of the native MAVS signaling pathway. (A) SUMO* cleaved off from the SUMO+-MAVSCARD fusion protein was electroporated into the reporter cell line as negative control. (B) Untreated MAVSCARD filament was electroporated into the reporter cell line. (C) MAVSCARD filaments after ultrasonication in an ultrasonic bath was electroporated into the reporter cell line. (D–F) The population of GFP-positive cells shown in A–C was quantified by flow cytometry. (G) Superposition of the solution NMR structure of MAVSCARD (PDB 2MS8, lime green) with the previously published MBP-fused MAVSCARD 1–93 crystal structure (PDB ID code 2VGQ, shown in wheat) (22). (H) Negative stain EM images of recombinant MAVSCARD filaments purified under nondenaturing conditions from E. coli. (I) Negative stain EM images of reassembled MAVSCARD filaments after monomerization at low pH. The filaments are longer, most likely due to growth at high concentration and less handling. (J) Superposition of a 25-ms PDSD spectrum of [UL-13C6]Glc labeled original MAVSCARD filaments (cyan) and reassembled MAVSCARD filaments (magenta). The spectra were acquired at 600.28-MHz proton frequency with a spin frequency of 13.5 kHz and at a temperature of 278 K. 1D trace at δ2 = 42.25 ppm is shown. The identical “fingerprint” pattern and 1D projection of both samples indicate the same structure and assembly pattern. Both spectra are plotted with the first contour level cut at 4.7 times the white noise level of the spectrum, and each following contour level was multiplied by 1.2. Molecular figures were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

Table S1.

Acquisition parameters for solution and ssNMR spectra

| NMR experiment | Acquisition parameters | ||||

| Acquisition time | Recycle delay/measurement time | Mixing time (ms) | |||

| t1/ms | t2/ms | t3/ms | |||

| ssNMR | |||||

| Uni-CARD DARR | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 1.75 s/11 h | 50 |

| Uni-CARD DARR | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 1.75 s/12 h | 100 |

| Uni-CARD DARR | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 1.75 s/14 h | 150 |

| Uni-CARD DARR | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 1.75 s/18 h | 250 |

| Uni-CARD DARR | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 3 s/25 h | 400 |

| Uni-CARD DARR* | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 1.75 s/11 h | 15 |

| Dilu-CARD DARR | 24.5 | 15.5 | — | 3 s/135 h | 400 |

| 3D-Uni-NCACX | 15.4 | 4.2 | 10.3 | 2.6 s/153 h | 250 |

| 3D-Uni-NCOCX | 15.4 | 4.2 | 13.7 | 2.7 s/138 h | 250 |

| [2-13C]Glc -NCA* | 21.5 | 16.0 | — | 2.6 s/16 h | — |

| [1-13C]Glc PDSD | 24.6 | 15.6 | — | 1.8 s/93 h | 250 |

| [1-13C]Glc PDSD | 24.6 | 15.6 | — | 1.7 s/94 h | 1,000 |

| [2-13C]Glc PDSD | 24.6 | 15.6 | — | 1.8 s/93 h | 250 |

| [2-13C]Glc PDSD | 24.6 | 15.6 | — | 1.7 s/94 h | 1,000 |

| [1/2-13C]Glc PDSD | 24.6 | 15.6 | — | 1.7 s/157 h | 1,000 |

| [1-13C]Glc PAIN | 22.5 | 16.0 | — | 2.3 s/42 h | — |

| [2-13C]Glc PAIN | 22.5 | 15.0 | — | 2.3 s/42 h | — |

| Solution state NMR | |||||

| 15N-HSQC | 122.4 | 45.1 | — | 1 s/0.5 h | — |

| 13C-HSQC (ali.) | 244.7 | 9.1 | — | 1 s/0.5 h | — |

| 13C-HSQC (aro.) | 122.4 | 42.4 | — | 1 s/2 h | — |

| HNCO | 121.7 | 14.8 | 20.6 | 1 s/16 h | — |

| HN(CA)CO | 121.7 | 13.2 | 23.6 | 1 s/36 h | — |

| HNCACB | 243.4 | 12.3 | 15.3 | 1 s/52 h | — |

| CBCA(CO)NH | 121.7 | 14.8 | 6.4 | 1 s/22 h | — |

| HH15N-TOCSY | 113.6 | 26.3 | 21.3 | 1 s/54 h | 60 |

| HH13C-TOCSY | 113.6 | 10.3 | 21.3 | 1 s/81 h | 60 |

| HH13C-NOESY (ali.) | 85.2 | 7.1 | 17.9 | 1 s/72 h | 80 |

| HH13C-NOESY (aro.) | 85.2 | 11.9 | 17.9 | 1 s/72 h | 80 |

| HH15N-NOESY | 85.2 | 20.5 | 17.9 | 1 s/68 h | 80 |

| HSQC-T1† | 104.4 | 45.1 | — | 1 s/36 h | — |

| HQC-T2‡ | 104.4 | 45.1 | — | 1 s/36 h | — |

| 1H-15N NOE§ | 91.7 | 13.2 | — | 8 s/24 h | — |

HSQC-T1, HQC-T2, and 1H-15N NOE spectra were collected at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III 700 MHz NMR spectrometer. All other spectra were collected on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz NMR spectrometer.

13C-13C DARR spectra and 15N-13C NCA spectra of MAVSCARD filament were recorded in the presence and absence of 100 mM Gd-DTPA.

HSQC with a delay for inversion recovery.

HSQC with Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) delay.

HSQC spectra were recorded in an interleaved manner for NOE and NO NOE where NO NOE is a standard HSQC; NOE is preceded by proton saturation transfer step.

The resonance assignment had been previously achieved on a single, uniformly 13C,15N-labeled sample (23). Dihedral angles and H-bonds were calculated from the chemical shifts of backbone nuclei with TALOS+ (25). MAVSCARD has excellent spectroscopic properties with good line widths of ∼75–80 Hz even for uniformly 13C-labeled samples ([UL-13C6]Glc) (Fig. S2A), suggesting a reproducibly high degree of microscopic order within the NMR samples. This high spectroscopic quality allowed the unambiguous determination of many intraresidue and sequential cross-peaks from a set of dipolar-assisted rotational resonance (DARR) experiments with short mixing times (Table S1), as well as from 3D NCACX and NCOCX spectra (Fig. 1 F and G). Assignments were considered to be unambiguous if they were either frequency unambiguous within a ±0.21-ppm tolerance window or supported by an extensive network of intraresidue and sequential restraints (Fig. 1 F and G). Short- and medium-range restraints could be unambiguously assigned using these criteria. However, spectral crowding would severely complicate the unambiguous manual assignment of further medium- and long-range restraints, and additional ambiguities exist in homo-oligomeric assemblies as cross-peaks could arise either from intra- or interprotomer contacts. Thus, we used a strategy that relies on sparse 13C-labeling to reduce spectroscopic assignment ambiguities (26, 27) and on mixed samples with differential isotopic labeling patterns to distinguish between intra-and interprotomer cross-peaks (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). To achieve the latter, we recorded long mixing time DARR and PDSD spectra on samples that were labeled with 15N and either [UL-13C6]Glc, [1-13C]Glc, or [2-13C]Glc and compared them to a 400-ms DARR spectrum of a [UL-13C6]Glc-labeled sample that was diluted 1:6 with unlabeled MAVSCARD. Any cross-peak that was absent in the diluted sample was considered to be potentially interprotomer and was removed from the set of restraints used for the protomer structure calculation. In addition, a PDSD spectrum was recorded on a 1:1 mixture of [1-13C]Glc and [2-13C]Glc-labeled MAVSCARD. Any resonance present in this spectrum, but not in the spectra of the individual [1-13C]Glc and [2-13C]Glc samples, was also removed from the set of intraprotomer cross-peaks (Fig. 2). To achieve unambiguous assignments of medium- and long-range restraints from this set, we relied on the long mixing time PDSD and on proton-assisted insensitive nuclei (PAIN) spectra of the sparsely labeled samples. These spectra exhibited significantly improved 13C line widths of 40–45 Hz and chemical shift deviations of less than 0.04 ppm for intraresidual and sequential cross-peaks (26, 27). Thus, we could assign 859 short- and medium-range intraprotomer distance restraints and 64 long-range ones (Table S2) either as frequency-unambiguous within a ±0.12-ppm tolerance window (Fig. 1 A–C) or, in cases where no more than three assignment options existed within this tolerance window, assignments were accepted as network unambiguous if there is extensive restraints (>3) between the two residues and if supported by other unambiguously assigned cross-peaks. The calculation of the protomer structure made use of in total 923 unambiguous restraints along with additional 2,185 ambiguous restraints.

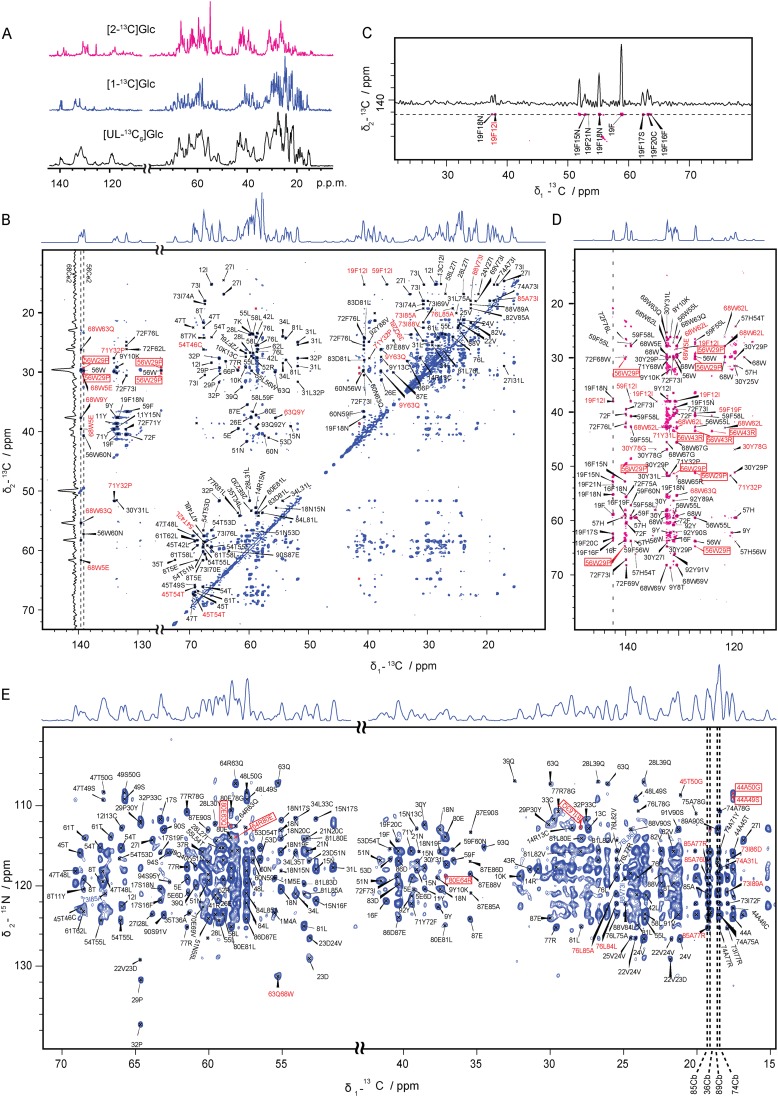

Fig. S2.

Spectra and unambiguous assignments of sparsely ([2-13C] Glc and [1-13C] Glc) labeled samples used for distance restraints determination. (A) 1D spectra of [2-13C] Glc, [1-13C] Glc, and [UL-13C6] Glc labeled samples. The line widths of the sparsely ([2-13C] Glc and [1-13C] Glc) labeled samples are ∼1.5–1.8 times narrower than those of the [UL-13C6] Glc labeled sample. (B) 2D PDSD spectrum of [1-13C]Glc labeled MAVSCARD filaments recorded at 600.28-MHz proton frequency with a mixing time of 1,000 ms. The excerpt shown in Fig. 1 is marked by dashed lines, and the 1D trace of 68WCe2 is shown to indicate the line width and S/N ratio. (C and D) Aromatic region of 2D 1,000-ms PDSD spectrum of [2-13C]Glc labeled MAVSCARD filaments. The signals from the aromatic region are typically weaker than those from the aliphatic region and thus represent the lowest signal-to-noise values. The excerpt shown in C is marked by dashed lines in D, and the 1D trace of 19F is shown to indicate the line width and S/N ratio. (E) 2D PAIN spectrum of [1-13C]Glc labeled MAVSCARD filaments recorded at 600.28-MHz proton frequency. The excerpt shown in Fig. 1 is marked by dashed lines. Approximately 57% of peaks could be assigned unambiguously including intraresidue cross-peaks. In B–E, all intraprotomer distance restraints are labeled as follows: short, medium range distance restraints (black), and long range distance restraints (red). All interprotomer distance restraints are labeled with a red box. Peaks that could not be unambiguously assigned are not labeled. All spectra were plotted at the same contour level; the first contour level was cut at 4.7 times the white noise level of the spectrum, and each following contour level was multiplied by 1.2.

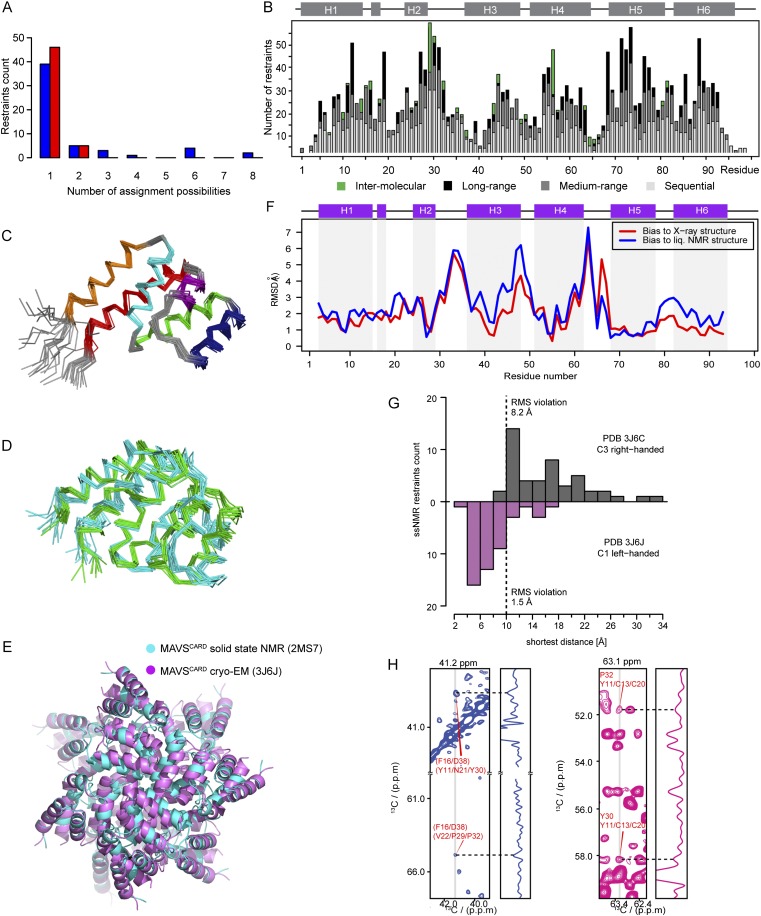

Fig. 1.

Intraprotomer distance restraints obtained in the ssNMR spectra of MAVSCARD filament. (A) Sections of 2D PDSD spectra of [1-13C]Glc (blue) labeled MAVSCARD filament. (B) Sections of 2D PDSD spectra of [2-13C]Glc (magenta) labeled MAVSCARD filament. (C) Sections of the 2D PAIN spectrum of [1-13C]Glc labeled MAVSCARD filament. The chemical shifts of 74A Cb and 89A Cb (18.54 and 18.66 ppm) and of 36A Cb and 85A Cb (19.21 and 19.33 ppm) are well distinguishable. (D and E) Structural models showing long-range intraprotomer distance restraints denoted in A and C by black boxes. (F and G) Strip plots of 3D 250-ms NCACX spectrum (teal) of [UL-13C6]-Glc labeled MAVSCARD filament. Unambiguous assignments of short and medium range distance restraints are indicated. Dashed lines between sequential residues highlight the dense network unambiguous assignments. All intraprotomer distance restraints are labeled as follows: short, medium (black), and long range distance restraints (red). All spectra were plotted at the same contour level; the first contour level was cut at 4.7 times the white noise level of the spectrum, and each following contour level was multiplied by 1.2. Molecular figures were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

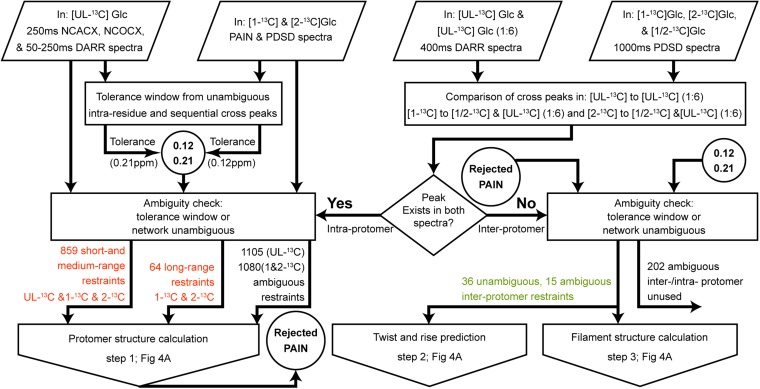

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the distance restraints assignment procedure. The flowchart presents the workflow for the unambiguous and ambiguous assignment of intra- and interprotomer solid state NMR distance restraints. Input data are represented by tilted rectangles, processing steps by rectangles, conditions for decision-taking by a rhombus, intermediate outputs applied to downstream processing steps by circles, and the final output feeding into the structure determination process depicted in Fig. 4A by arrows. Numbers for unambiguous intraprotomer restraints are written in red and numbers for interprotomer restraints in green.

Table S2.

List of 64 unambiguously identified long-range intraprotomer restraints, 36 unambiguously identified interprotomer restraints from all spectra mentioned in Table S1, and 47 unique interprotomer restraints assigned after grid search and ARIA MAVSCARD filament structure calculation

| Unambiguous long-range intraprotomer restraints | Unambiguous interprotomer restraints | Interprotomer restraints after ARIA calculation | |

| E5Cb-W68Cd1 | Y71Cg-P32Cb | R14C-P29Cd | K10Ca-P29Ca/P32Ca |

| E5Cb-W68Cd2 | Y71Cg-P32Cd | R14C-P29Cg | R14C-P29Cd |

| E5Cd-G67Ca | I73Cg1-A85Cb | N18Nd2-A36Cb | R14C-P29Cg |

| Y9Cb-Q63Ca | I73Cg1-V88Cg1 | E26Ca-R64Cz | R14Ca-P32Cd |

| Y9Cb-Q63Cb | I73Cg1-V88Cg2 | P29Ca-R14Ca | F16Cb-P29Ca |

| Y9Cb-Q63Cg | I73Cg2-A85Cb | P29Ca-W56Ce2 | F16Cb-Y30Cb |

| I12Cg2-F19Cb | I73Cg2-V88Cg1 | P29Cb-W56Ca | N18Nd2-A36Cb |

| I12Cb-F19Ca | L84N-L76Cd2 | P29Cb-W56Ce2 | E26Ca-R14Cb/R37Cb |

| I12Cb-F19Cz | A85N-I73Ca | P29Cd-W56Ca | E26Ca-R64Cz |

| I12Cg1-F19Cz | A85N-L76Cd2 | P29Cd-W56Ce3 | P29Ca-R14Ca |

| I12Cb-F59Ca | D86N-I73Cg2 | P29Cg-W56Cd1 | P29Ca-W56Ca |

| I12Cg2-F59Cb | D86N-L76Cd2 | P29Cg-W56Ce2 | P29Ca-W56Ce2 |

| Y30Cb-A75Cb | V88Cb-I73Cb | P29Cg-W56Ce3 | P29Cb-F16Cb |

| L31Cd1-A75Cb | V88Cb-I73Cg1 | Y30C-N15Cb | P29Cb-W56Ca |

| L31Cd1-A75Ca | A89Ca-I73Cb | R37Ca-N18Nd2 | P29Cb-W56Ce2 |

| L31Cg-A75Ca | A89Ca-I73Cg1 | R43Cd-H57Ce1 | P29Cd-W56Ce3 |

| Q39Ne2-L28Ca | A89N-I73Cg2 | R43Cd-W56Ce3 | P29Cg-F16Cb |

| Q39Ne2-L28Cda | R43Cd-W56Cz3 | P29Cg-W56Cd1 | |

| Q39Ne2-L28Cg | A44Cb-G50N | P29Cg-W56Ce2 | |

| T45Cb-T54Ca | A44Cb-S49Ca | P29Cg-W56Ce3 | |

| T45Cb-T54Cb | A44Cb-S49Cb | Y30C-N15Cb | |

| T54Cb-L42Ca | A44Cb-S49N | Y30Ca-C13Ca | |

| T54Cb-C46Cb | W56Cd1-P29Ca | P32Cd-Y11Ca/C13Ca | |

| T54Ca-T45Ca | W56Cd1-P29Cb | T35Ca-K10Cd | |

| T54Ca-C46Ca | W56Cd1-P29Cd | R37Ca-N18Nd2 | |

| L55Ca-F16Cg | W56Cd1-R43Cd | R43Cd-H57Ce1 | |

| L55Cb-F16Cg | W56Cd1-V25Cb | R43Cd-W56Ce3 | |

| L55Cg-V22Ca | W56Ce2-P29Cd | R43Cd-W56Cz3 | |

| F59Ce-F19Cb | W56Ce2-R43Cd | A44Cb-G50Ca | |

| F59Cg-I12Cb | W56Ce2-Y30Ca | A44Cb-G50N | |

| L62Ca-W68Cd1 | R64Cd-L81N | A44Cb-S49Ca | |

| L62Cb-W68Cd1 | R64Cz-L81Cd2 | A44Cb-S49Cb | |

| L62Cb-W68Cd2 | R65Cz-L81Cg | W56Cd1-P29Ca | |

| L62Cg-W68Cd1 | E80Ca-Q63Ne2 | W56Cd1-P29Cb | |

| L62Cg-W68Cd2 | E80Cg-R64Ne | W56Cd1-P29Cd | |

| Q63Cb-W68Cd1 | L81Cd1-Q63Ne2 | W56Cd1-R43Cd | |

| Q63Cb-W68Cd2 | W56Cd1-V25Cb | ||

| W68Ce2-D6Ca | W56Ce2-P29Cd | ||

| W68Ce2-Y9Cb | W56Ce2-R43Cd | ||

| W68Ce2-Q63Ca | R64Cd-L81N | ||

| W68Ce2-Q63Cb | R64Cz-L81Cd2 | ||

| W68Ne1-Q63Ca | R65Cz-L81Cg | ||

| W68Ce3-Q63Cb | K7Ca-T35Cb | ||

| W68Cd1-Q63Ca | E80Ca-Q63Ne2 | ||

| W68Ch2-L62Cb | E80Cg-R64Ne | ||

| W68Cz2-L62Cg | L81Cd1-Q63Ne2 | ||

| Y71Cg-L31Cb | V82Cg2-R65Ca/P66Cd |

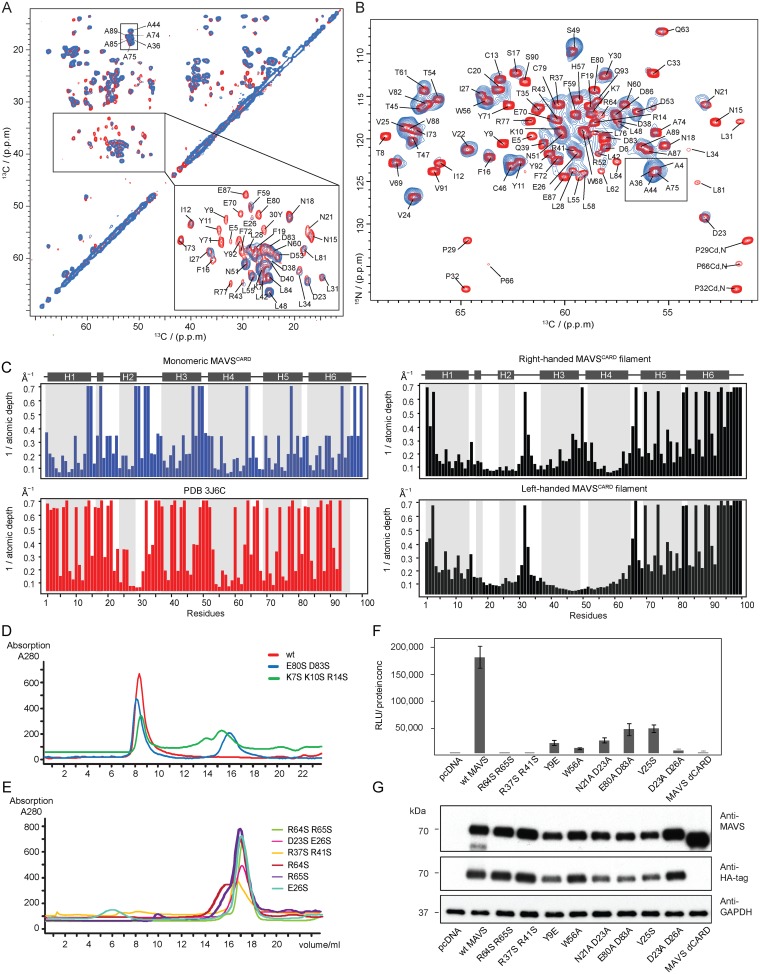

Interprotomer distance restraints are of crucial importance for the calculation of the filament structure. Thus, cross-peaks were considered and accepted as unambiguous interprotomer restraints only if they met the following two criteria: (i) cross-peak is absent in the spectrum of the 1:6 diluted [UL-13C6]Glc sample (Fig. 3 A and C) or present only in the spectrum of the mixed [(1/2)-13C]Glc labeled sample (Fig. 3B) and (ii) frequency-unambiguous assignment within a ±0.12-ppm tolerance window (Fig. 3 A–D) or network unambiguous as defined above; most cross-peaks were further substantiated by one of the following criteria: (iii) at least two unambiguous cross-peaks for each pair of residues (Fig. 3 A–D) and (iv) resonances in PAIN-CP spectra of [1-13C]Glc and [2-13C]Glc labeled samples (Fig. 3 E and F) were incompatible with the protomer structure, leaving only frequency-unambiguous interprotomer assignment options. In total, 51 interprotomer distance restraints were identified, of which 36 were unambiguous, relating to 15 pairs of interacting residues (Table S2). Fifteen more had two to eight interprotomer assignment options (Fig. S3 A and H).

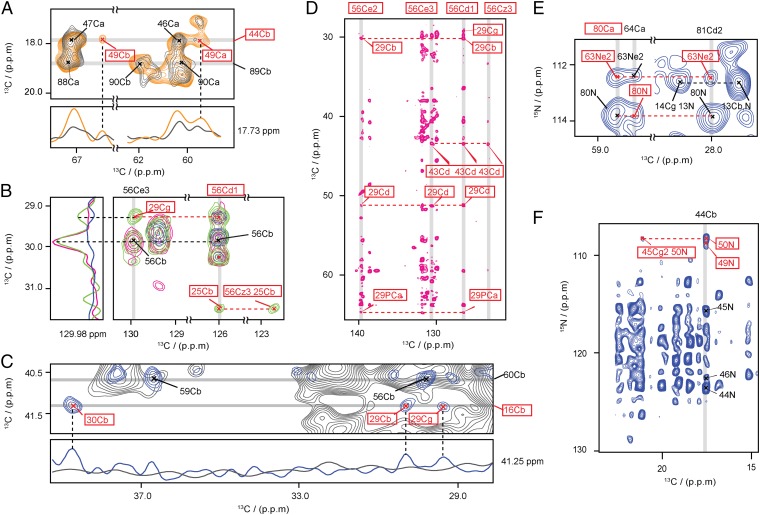

Fig. 3.

Collection of interprotomer ssNMR distance restraints. All spectra were plotted at the same contour level; the first contour level was cut at 4.7 times the white noise level of the spectrum, and each following contour level was multiplied by 1.2. (A and C) Superposition of 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra of [1-13C]Glc (blue) and [UL-13C6]Glc (orange) labeled MAVSCARD with that of 1:6 diluted [UL-13C6]Glc (gray) labeled MAVSCARD. 1D slices at δ2 = 17.73 ppm (A) and δ2 = 41.25 ppm (C) are shown with dashed line to indicate the interprotomer peaks. (B) Superposition of the 2D PDSD of mixed [1/2-13C]Glc (green) labeled MAVSCARD with the 2D PDSD of [1-13C]Glc (blue) and [2-13C]Glc (magenta) labeled MAVSCARD. 1D traces at δ1 = 129.9 ppm are shown with dashed line to indicate the interprotomer peaks. (D) Section of the 2D PDSD of [2-13C]Glc (magenta) labeled MAVSCARD. The network between unambiguously assigned interprotomer restraints is indicated by dashed lines. (E and F) Sections of the 2D PAIN spectrum of [1-13C]Glc labeled MAVSCARD containing both intra- and interprotomer distance restraints. The unambiguous restraints shown in A also appear in F. All interprotomer distance restraints are labeled in boxed red.

Fig. S3.

Tertiary structure of the MAVSCARD protomer and quaternary structure of the MAVSCARD filament calculated with ssNMR distance restraints. (A) The number of assignment possibilities for interprotomer restraints before and after ARIA filament calculation. Histogram of the number of nonredundant interprotomer restraints as a function of the number of assignment possibilities used as input for the grid search (blue) and remaining ambiguity after the filament structure calculation using ARIA (red). The grid search approach and ARIA calculation could work with a certain extend of spectroscopic ambiguity of interprotomer restraints in addition to full protomer ambiguity. (B) The structure of MAVSCARD filament was calculated with both intra- and interprotomer distance restraints. The number of distance restraints for each residue after the structure calculation is plotted against the sequence. The secondary structure is indicated on the top of the chart. (C) Backbone superposition of the 10 lowest-energy structures of MAVSCARD protomer determined by ssNMR. (D) Overlay of the MAVSCARD protomer structure (PDB ID code 2MS7; shown in cyan) with the structure of monomeric MAVSCARD determined by solution NMR (PDB ID code 2MS8; shown in green). (E) Superposition of the ssNMR (cyan) and the 3J6J cryo-EM (6) (purple) structures of MAVSCARD filament structure. Eight protomers in the cryo-EM PDB structure are represented (M − 3 to M + 4). The Ca RMSD between the two structures is 3.05 Å (residues 2–95). The resolution of the 3J6J cryo-EM structure is 3.64 Å. (F) RMSD per residue along the MAVSCARD sequence between the MAVSCARD protomer structure in the filament and the X-ray structure (red) or the monomeric solution NMR structure (blue). Positions of helices 1–6 are shown on top. The RMSD was calculated on Ca atoms after superimposing the average protomer structure of MAVSCARD in filaments with the X-ray structure (PDB ID code 2VGQ) (22) and with the average solution NMR structure. Largest RMSD values were observed in interhelical loop regions in both cases and in helix 3 when comparing to the solution NMR structure. (G) Distribution of measured distances for the ssNMR interprotomer restraints in two cryo-EM structures of MAVSCARD filaments from Xu et al. (5) (Upper) and Wu et al. (6) (Lower). For each restraint, the shortest distance is obtained from among all possible pairs of protomers in the filament structure. (H) Sections of 2D PDSD of [1-13C]Glc (blue) and [2-13C]Glc (magenta) labeled MAVSCARD show ambiguous interprotomer restraints used as input for the ARIA structure calculation.1D traces at δ1 = 41.2 and 63.1 ppm are shown with dashed line to indicate the interprotomer peaks. Molecular figures were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

Three-Step Structure Calculation of MAVSCARD Filaments.

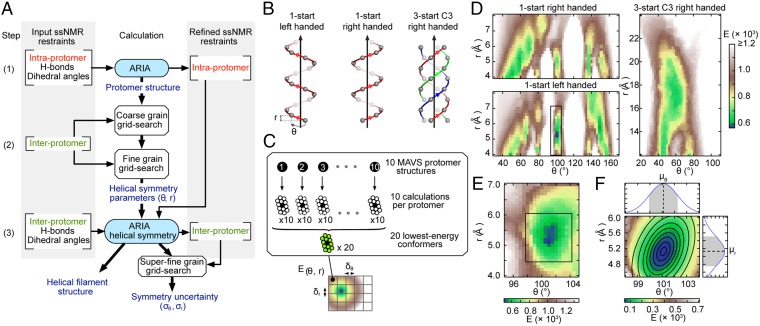

To determine the 3D atomic resolution structure of MAVSCARD helical filaments without prior structural knowledge, we conceived a three-step approach of (i) protomer structure determination, (ii) determination of helical symmetry parameters from interprotomer distance restraints via grid-search, and (iii) semiflexible calculation of the complete filament structure. This approach efficiently exploits the symmetric properties of the filamentous complex to unambiguously determine its unknown helical parameters (Fig. 4A). First, we used established iterative ARIA (28) protocols to determine the structure of the protomer from dihedral angles, H-bonds, and intraprotomer distance restraints. The ensemble of protomers is very well converged with a backbone RMSD of 0.60 ± 0.10 Å (Table S3) and exhibits the six-helix bundle Greek-Key topology characteristic for the death domain superfamily (Fig. 1 D and E and Fig. S3 C and D). The structure of the MAVSCARD protomer is based on a unique set of NMR signals with no indications for peak doubling (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2), indicating that all protomers in the filament are in the same conformation and are arranged homogeneously in a symmetrical manner along the filament axis. This finding is consistent with known structures of oligomeric complexes in the death domain superfamily, all of which exhibit helical or pseudohelical symmetries, albeit with variable parameters and handedness (21).

Fig. 4.

Grid-search (GS) for helical symmetry and MAVSCARD filament structure calculation. (A) Flowchart of the three-step structure calculation protocol of MAVSCARD filament structure from ssNMR restraints. (B) Three types of helical symmetry probed in the GS approach. θ and r represent the helical twist and rise, respectively. (C) Schematic representation of the GS approach. The grid is filled with the median energy (E(θ,r)) of the 20 best helical conformers for each (θ,r) combination using δθ and δr increments. (D) Result of the coarse-grained GS. Black box indicates the region explored in the fine-grained GS. (E) Results of the fine-grained GS. Black box indicates the region explored in the superfine-grained GS. (F) Result of the superfine-grained GS with the fitted bivariate Gaussian function on p(θ,r) and the corresponding univariate Gaussian distributions for θ and r on the top and left sides, respectively.

Table S3.

Summary of structural restraints and structure statistics of MAVSCARD filament determined by ssNMR

| Statistics | MAVSCARD protomer | MAVSCARD filament |

| Number of restraints* (ssNMR distance restraints) | ||

| Total | 2,554 | 2,547 |

| Intraprotomer | 2,554 | 2,500 |

| Interprotomer | 0 | 47 |

| Intraresidue (|i-j| = 0) | 531 | 540 |

| Sequential (|i-j| = 1) | 525 | 557 |

| Medium-range (2 ≤ |i-j| < 5) | 346 | 384 |

| Long-range (|i-j| ≥ 5) | 222 | 249 |

| Ambiguous | 930 | 770 |

| Dihedral angle restraints (φ/ψ) | 182 (91/91) | 182 (91/91) |

| Hydrogen bonds restraints | 86 | 86 |

| Restraints statistics† (RMS of distance violations) | ||

| ssNMR restraints | 0.011 ± 0.001 Å | 0.073 ± 0.005 Å |

| H-bonds restraints | 0.031 ± 0.003 Å | 0.026 ± 0.005 Å |

| RMS of dihedral violations | 0.721 ± 0.115° | 0.551 ± 0.063° |

| RMS from idealized covalent geometry | ||

| Bonds | 0.003 ± 0.001 Å | 0.001 ± 0.000 Å |

| Angles | 0.455 ± 0.009° | 0.318 ± 0.007° |

| Impropers | 1.097 ± 0.042° | 0.200 ± 0.012° |

| Structural quality† (Ramachandran statistics‡) | ||

| Most favored regions | 90.8 ± 1.2% | 90.1 ± 1.9% |

| Allowed regions | 8.9 ± 1.4% | 9.3 ± 1.8% |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.3 ± 0.5% | 0.7 ± 0.6% |

| Disallowed regions | 0.0 ± 0.0% | 0.0 ± 0.0% |

| Coordinates precision§ | ||

| All backbone atoms | 1.48 ± 0.41 Å | 0.97 ± 0.54 Å |

| All heavy atoms | 1.77 ± 0.38 Å | 1.38 ± 0.46 Å |

| All backbone atoms (3–94) | 0.60 ± 0.10 Å | 0.42 ± 0.07 Å |

| All heavy atoms (3–94) | 1.13 ± 0.09 Å | 0.93 ± 0.09 Å |

| Ca RMSD vs. reference structure¶ | ||

| Solution NMR | 2.58 Å | 2.37 Å |

| X-ray (2VGQ1) | 2.12 Å | 1.82 Å |

Number of nonredundant restraints for one protomer.

Average values and SDs over the final ensemble.

Percentage of residues in the Ramachandran plot regions determined by PROCHECK.

Average RMSD over the ensemble’s atomic coordinates with respect to the average structure.

RMSD of the average ssNMR protomer structure with respect to the reference structure for secondary-structure elements (residues 3:14, 16:18, 24:39, 36:48, 51:63, 68:78, and 82:93).

To determine the parameters defining the symmetry of the MAVSCARD filament, we next deviced a grid-search approach that is independent of complementary techniques for the determination of helical symmetry parameters and handedness. Instead, it makes use of interprotomer ssNMR distance restraints and systematically explores the helical space in a given range of twist and rise values (Fig. 4C). Existing grid-based methods are limited to symmetric oligomers with point symmetries (29–31). To accommodate helical symmetries, we therefore based our grid-search on a previously proposed approach for efficient modeling of symmetric oligomers from NMR data for any given fixed symmetry (32). This approach is particularly suitable for oligomers with point symmetry because the symmetry parameters can be inferred from the finite number of protomers in the oligomer. However, this is not possible for filaments with helical symmetry. Twist and rise values were thus separately and regularly incremented to generate an ensemble of helical conformations for every combination of these two parameters. Each symmetry-constrained helical conformation was determined by semiflexible energy minimization of 100 starting conformations using the previously solved protomer structure and 51 interprotomer restraints. At this stage, each interprotomer restraint was not assigned to specific protomer pairs but rather applied between a given protomer and all other protomers in the modeled filaments, in a protomer-ambiguous fashion (Fig. 5D and Table S4). In addition to left-handed and right-handed 1-start helices, which represent the simplest description of a helical arrangement, we also tested 3-start helices with C3 symmetry (three strands related by a threefold rotational symmetry), as previously reported by cryo-EM reconstruction (5) (Fig. 4B). Such a large grid-search can be performed because we built on an efficient approach to constrain the symmetry during the minimization (32). Here, only one protomer is explicitly (all atoms) modeled and symmetry related protomers only exist as virtual images. Because the number of strands is not a free parameter, it is required to perform separate grid-search calculations for every Cn symmetry to be probed. This approach of strict symmetry was shown to work successfully on oligomers with helical and point symmetry, and computational time is largely independent of the number of protomers (32) or strands.

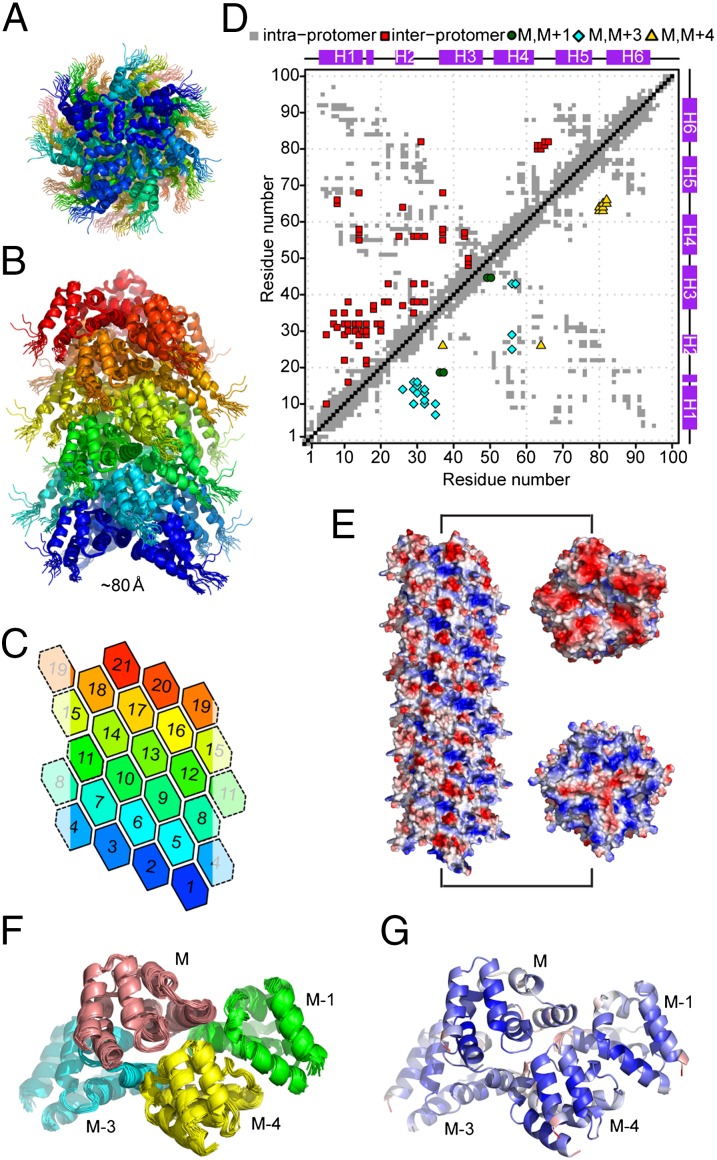

Fig. 5.

Structure of MAVSCARD filament calculated with ssNMR distance restraints. (A and B) Side and top views of the MAVSCARD filament structure ensemble determined with ARIA. Protomers are colored as in C. (C) 2D lattice representation of the MAVSCARD filament topology. Protomers are represented as hexagons, numbered according to the 1-start helix. (D) Restraint map of the initial (Upper) and final (Lower) set of ssNMR distance restraints. In the initial set, interprotomer restraints are ambiguous and not assigned to specific protomers. In the final set, restraints were specifically assigned by ARIA between protomers M and M + 1 (green circles), M + 3 (cyan diamonds), or M + 4 (yellow triangles). The positions of helices 1–6 of MAVSCARD are shown on the top and left sides with purple boxes. (E) Electrostatic potential plot of MAVSCARD filament. The cross sections of the electrostatic potential plot of MAVSCARD filament show mostly negative charges (red) on one side and positive charges (blue) on the other side. (F) Cartoon representation of the ensemble of 10 refined conformers of a MAVSCARD tetrameric subcomplex. The four MAVSCARD protomers (M, M − 1, M − 3, and M − 4) are colored separately. For sake of clarity, C- and N-terminal residues have been removed. The average backbone RMSD of the subcomplex ensemble is 0.68 ± 0.12 Å and 0.51 ± 0.10 Å for the protomer M (residues 3–95). (G) Cartoon representation of the average MAVSCARD tetramer structure colored by the RMS fluctuation (RMSF) among the ensemble. The largest RMSF values (red) were observed for the N-terminal parts of helix 1 and 3. Molecular figures were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

Table S4.

Detailed results of the grid-search calculations performed on MAVSCARD filaments

| Parameter | Coarse-grained | Fine-grained | Superfine-grained | ||

| Hand | Left | Right | Right | Left | Left |

| Cn symmetry | C1 | C1 | C3 | C1 | C1 |

| θ range (°) | [0, 180] | [0, 180] | [0, 120] | [95, 105] | [98, 104] |

| r range (Å) | [4, 8] | [4, 8] | [12, 24] | [4, 7] | [4.5, 6] |

| Δθ (°) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Δr (Å) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| θmin (°) | 100 | 101 | 101 | ||

| rmin (Å) | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 | ||

| CPU time per conformer (s) | ∼2.4 | ∼2.4 | ∼2.9 | ∼2.4 | ∼2.4 |

| No. conformers calculated | 191,100 | 191,100 | 372,100 | 311,100 | 189,100 |

| No. CPU used | 182 | 182 | 122 | 126 | 122 |

| Total computational time (min) | 42 | 42 | 147 | 98 | 62 |

For each grid-search, the hand of the tested helical symmetry is given, along with the ranges for rotational twist (θ) and translational rise (r), the grid increments for θ and r, and the Cn symmetry applied. θmin and rmin are the respective values of θ and r that give rise to the absolute minimal energy () in the given grid-search. Additionally, the average computational time to calculate a single helical conformer is given (in seconds), along with the overall number of conformers calculated, the number of CPU simultaneously used and the total computation time (in minutes).

The result of an initial coarse-grained grid-search with relatively large twist and rise increments yielded a very well-defined minimum of energy corresponding to a left-handed helical structure with a twist of 100° and a rise of 5.2 Å (Fig. 4D). The symmetry was further refined to a twist of 101° and rise of 5.1 Å with a finer-grained search using smaller increments on a reduced range (Fig. 4E). We confirmed the accuracy of the approach with a higher-resolution grid that converged to the very same twist and rise values (super fine-grained grid-search; Fig. 4F and Table S4). Our values are very close to the ones obtained by Wu et al. (6) (101.1° and 5.13 Å).

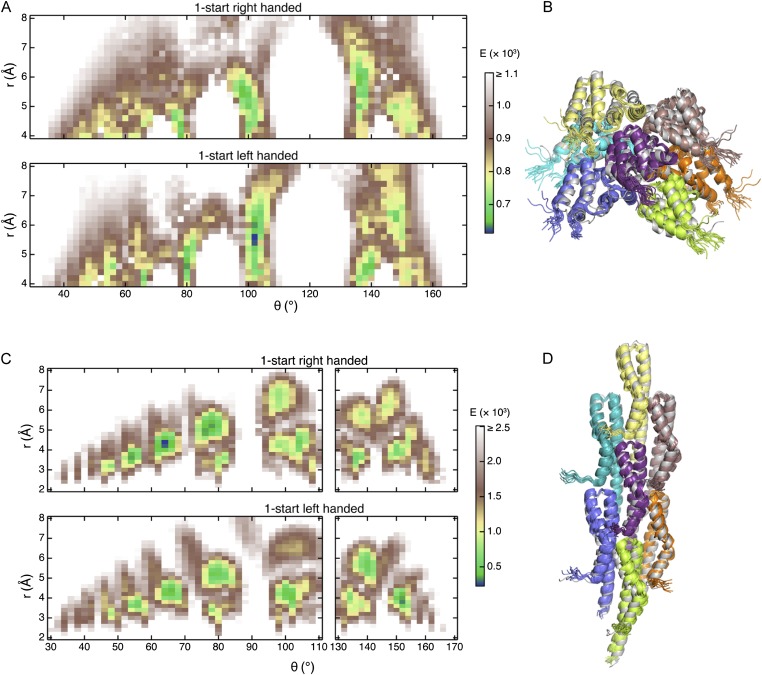

To further prove the applicability of our approach, we used the solution NMR structure of the MAVSCARD monomer determined at low pH as input structure (Fig. S4 A and B). The symmetry parameters, and in particular the handedness, could be well approximated, indicating that our approach is not sensitive to small differences in the input monomer structure. In addition, we performed a grid-search on the type III secretion system needle (Fig. S4 C and D). The result was very close to the values obtained by Loquet et al. (15, 17), suggesting that our approach is robust and will be generally applicable to determine the helical symmetry and the handedness of large protein assemblies.

Fig. S4.

Robust applicability of grid-search for determining the helical symmetry and the handedness of large protein assemblies. (A and B) Results of the coarse-grained grid-search for MAVSCARD filament using the solution NMR structure as initial protomer structure. (A) The median energy of the grids is shown for the right- (Upper) and left-handed (Lower) helix. Twist angles around 0° and 180° give rise to high-energy barriers and are not shown for clarity. The absolute minimal energy of the grid corresponds to a left-handed helix of twist θmin = 102° and rise rmin = 5.6 Å. These values differ only by ∼1 SD from the values obtained with the ssNMR MAVSCARD protomer structure. (B) Superposition of the best solution of the grid-search (gray) with the 2MS7 structure ensemble (colored by protomers) for a heptameric complex (MAVSCARD protomers M, M ± 1, M ± 3 and M ± 4). The Ca RMSD between the two structures is 3.72 Å (residues 2–95). The correct topology of the three interprotomer interfaces is correctly found by the grid-search despite the slight conformational difference between the monomeric MAVSCARD structure in solution and its protomer structure in filaments. (C and D) Results of the coarse-grained grid-search for the type III secretion needle. (C) The median energy of the grids is shown for the right- (Upper) and left-handed (Lower) helix. Twist angles around 0°, 120°, and 180° gave rise to high-energy barriers and are not shown for clarity. The absolute minimal energy of the grid corresponds to a right-handed helix of twist θmin = 64° and rise rmin = 4.4 Å, very close to the values obtained by Loquet et al. using a Rosetta approach, assuming an 11-start helix (15) (∼64° and ∼4.3 Å). (D) Superposition of the best solution of the grid-search (gray) with the 2LPZ structure ensemble (colored by protomers) for a heptameric complex (Prgl protomers i, i ± 5, i ± 6, and i ± 11). The Ca RMSD between the two structures is 1.79 Å (residues 8–80). Molecular figures were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

We then determined a high-resolution structure of MAVSCARD filaments using the iterative ARIA/CNS methodology (33, 34) with an extension to include helical symmetry constraints (32). This strategy allowed us to automatically assign the initially protomer-ambiguous 51 interprotomer restraints to protomers M, M ± 1, M ± 3, and M ± 4 (Fig. 6 E and F) and to reestimate the set of intraprotomer restraints in the context of the helical filament. Although no significant changes to the protomer structure were observed, the set of long-range intraprotomer restraints was increased by ∼10%. Forty-three unique interprotomer restraints could be assigned unambiguously, and four more had two assignment options (Fig. S3A and Table S3). The structure of MAVSCARD filaments is shown in Fig. 5 A–C. Structural statistics are given in Table S3 and Fig. S3B. The ensemble of MAVSCARD structures is very well converged (backbone RMSD of 0.5 ± 0.1 Å over 21 protomers) and is very similar to the model of Wu et al. (6) when superimposing eight consecutive protomers (Fig. S3E). In this model (3J6J), only 17% of the atom pairs defined as ssNMR restraints have a distance greater than 10 Å, whereas in the 3J6C model (right-handed helix with C3 symmetry), more than 95% do (Fig. S3G). The threshold of 10 Å (8 Å upper bound + 2 Å) was chosen to account for alternative side chain conformations in the cryo-EM structures with regards to the ssNMR structure.

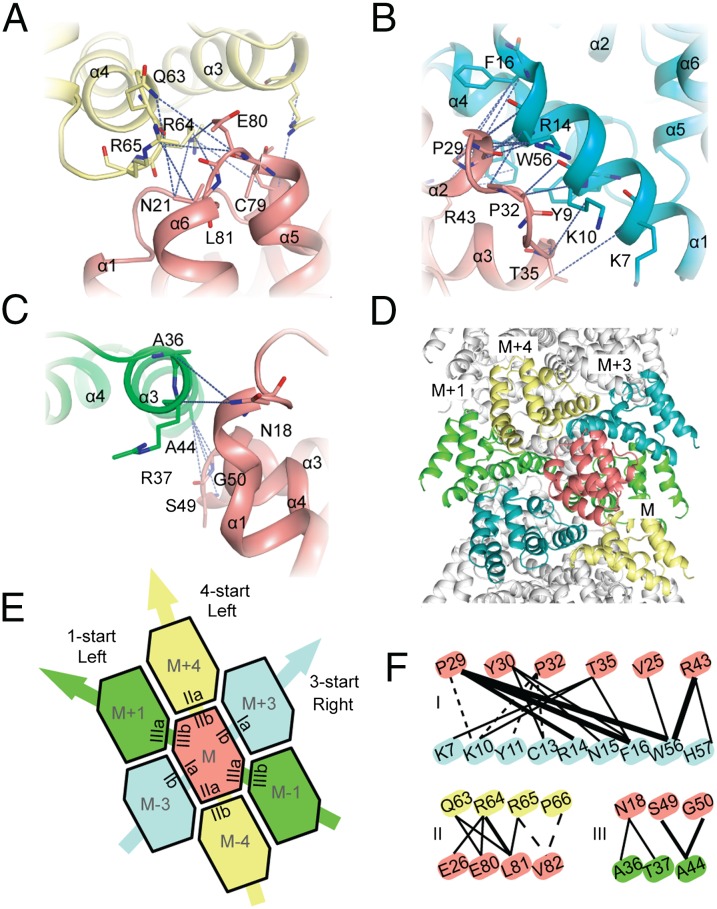

Fig. 6.

Interaction interfaces involved in assembly of MAVSCARD filament. (A–C) Three types of interaction interfaces were identified in the assembly of MAVSCARD filament. Key residues and interprotomer ssNMR distance restraints for each interface are labeled. (D) Cartoon diagram of the structure of MAVSCARD filament. (E) 2D lattice representing all three types of interfaces in the context of the MAVSCARD filament. (F) Schematic representation of interprotomer distance restraints for the three types of interfaces. Unambiguous and ambiguous distance restraints are plotted as solid and dashed lines, respectively. The thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of restraints.

The smallest entity describing all interprotomer contacts in the filament consists of four protomers M, M + 1, M + 3, and M + 4 (or, equivalently, M, M − 1, M − 3, and M − 4). Such a tetrameric subcomplex of the MAVSCARD filament structure was further refined without constraining the helical symmetry. The final ensemble has a backbone RMSD of 0.7 ± 0.1 Å (Fig. 5 F and G). The average twist and rise values confirmed the fixed parameters used for the previous ARIA calculation (101 ± 1° and 5.1 ± 0.5 Å). In addition, such an ensemble provides a first approximation of the uncertainty of the helical symmetry parameters compatible with the interprotomer distance restraints. This uncertainty was further analyzed from the super fine-grained grid-search where the spread of the twist and rise were estimated at 1.1° and 0.4 Å, respectively (Fig. S5 and SI Text). Although it is not possible to relate directly this data-derived uncertainty to an intrinsic feature of MAVSCARD filaments, we would like to stress that a variable twist angle has been observed for some helical filaments (2, 35).

Fig. S5.

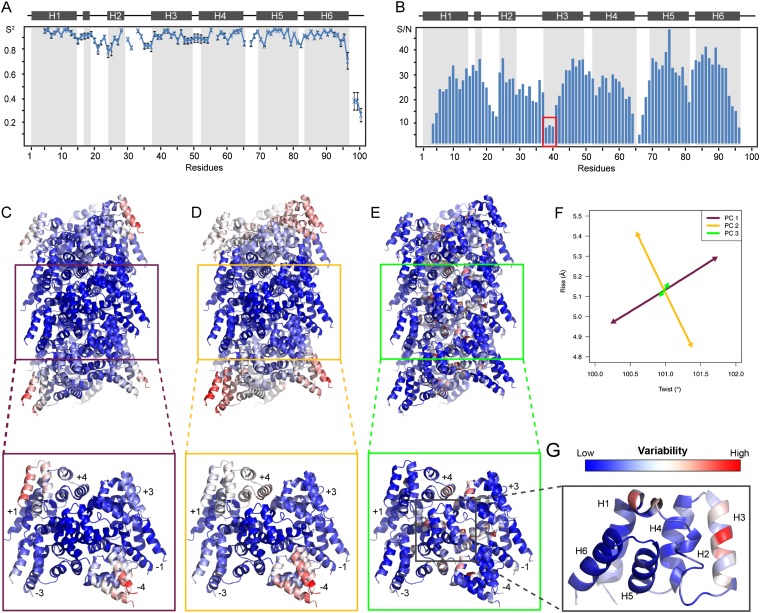

Flexibility analysis of MAVSCARD in the monomer and in the filament. (A) Dynamics of monomer MAVSCARD was determined on D23S E26S mutant by solution NMR. The S2 value is plotted against the sequence. The errors were determined from 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations of Brent’s implementation of Powel’s method for multidimensional minimization (61). (B) Signal-to-noise ratios of each residue in MAVSCARD filament in the 3D ssNMR CONCA experiment on a [UL-13C6] Glc labeled sample. The peak intensities are usually inversely correlated with the local mobility of the residues. Residues 38–40 of helix 3 (red box) appear to have higher local mobility in the filament than in the monomeric mutant D23S E26S. The secondary structure is indicated on the top of the chart. (C–G) Results of the PCA on samples of MAVSCARD helical conformations from the 2D Gaussian distribution. (C–E) (Upper) Cartoon representation of the MAVSCARD filament structure colored by the residue variability for the first (C), second (D), and third (E) principal components. (Lower) Central heptamer encompassing protomers M − 4, M − 3, M − 1, M, M + 1, M + 3, and M + 4. (F) First three principal components (PC1 PC2, and PC3) projected on the (θ,r) space. (G) MAVSCARD protomer structure colored by the variability from PC3. Molecular figures were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC).

Structure of the MAVSCARD Filament.

The MAVSCARD filament [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2MS7] has an outer diameter of ∼82 Å and no inner pore. Each protomer is in contact with six other protomers via three interfaces denoted Ia/Ib, IIa/IIb, and IIIa,IIIb (Fig. 6 A–D), which are preserved in death domain complexes determined to date (2, 21, 36). The IIIa/IIIb interface mediates the intrastrand contacts that form the left-handed 1-start helix. It is formed by residues of the C-terminal kink of helix α1 and the loop between helices α3 and α4 (IIIa) interacting with helix α3 (Fig. 6C). Interstrand contacts are mediated by the Ia/Ib and IIa/IIb interfaces. Alternatively, these interfaces can be described to form a 3-start, right-handed and a 4-start, left-handed helix, respectively (Fig. 6E). The Ia/Ib interface is formed by residues of helices α1 and α4 interacting with the tips of helices α2, α3 and the loop in between (Fig. 6B). In the IIa/IIb interface, the loop between helices α4 and α5 is in contact with the two loops connecting helices α1, α2 and α5, α6, respectively (Fig. 6A). Although the type II and III interfaces are dominated by polar and charged interactions, the type I interface is characterized by a mix of polar and hydrophobic interactions. In particular, the aromatic residues Y11, Y30, F16, and W56 contribute to this interface and give rise to multiple interprotomer distance restraints. The strong contribution of charged residues to all three interfaces is in agreement with our observation that MAVSCARD fibrils can be disassembled at low pH and is also reflected by loss-of-activity mutants generated by us (Fig. S6 D–G) and others (5, 37), which often target charged residues.

Fig. S6.

Validation of the MAVSCARD filament structure by solvent PRE and mutagenesis. (A–C) Surface accessibility of MAVSCARD filament probed by Gd-DTPA via ssNMR. (A) 25-ms DARR spectra of MAVSCARD filaments in the absence (red) and presence (blue) of Gd-DTPA. The lower boxed region is shown enlarged together with assignments. (B) NCA spectra of MAVSCARD filaments in the absence (red) and presence (blue) of Gd-DTPA. Loss of signal intensity on mixing with 100 mM Gd-DTPA is indicative of residues that are located near the surface of of MAVSCARD filaments. (C) Inverse of the average depth (Δ) of each Ca atoms from the solvent accessible surface of MAVSCARD monomer and three different MAVSCARD filament structures. Secondary structure elements are indicated on the top of the chart. (D and E) Size exclusion chromatography of MAVSCARD mutants by Superdex 200. Absorptions at 280 nm is plotted against the elution volumes. All of the mutants at the interaction surfaces completely or partially disrupt the formation of the filament. (F) Interferon-sensitive response element (ISRE) promoter activity of HA-tagged WT and mutant MAVS. WT MAVS, the dominant negative mutant MAVSΔCard, and various mutants were transiently expressed in HEK293T-ISG54-luciferase reporter cells. Cells were lysed after 48 h, and the MAVS signaling was tested by luciferase reporter assay and normalized by protein concentration. The y axis depicts the normalized relative light units (RLU/protein concentration). (G) Western blot of samples shown in F was performed to monitor the expression level of the transfected MAVS proteins with GAPDH as a loading control.

Cross-Validation of the Filament Structure.

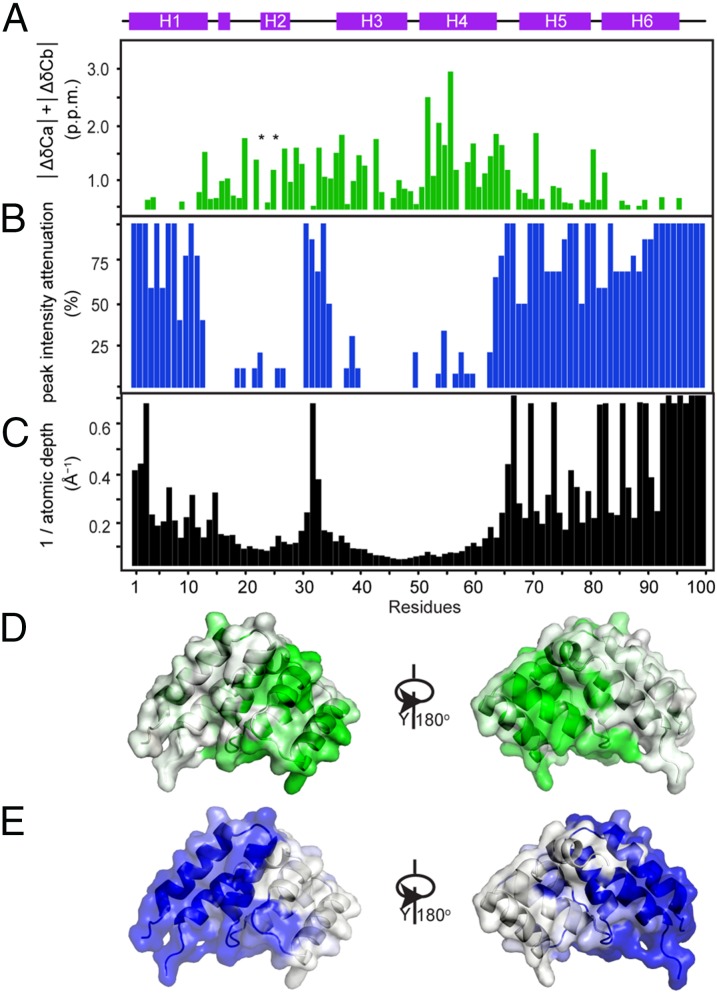

Toward an unbiased validation of our final structure, we probed the orientation and packing of the protomers within the filament by two independent experiments. First, we analyzed the solvent accessibility of individual residues by measuring the PRE effect of 100 mM gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentacetate (Gd-DTPA) added to the solvent. To have at least one signal for every amino acid that could be faithfully integrated, 13C-13C DARR spectra and 15N-13C NCA spectra of MAVSCARD filament were recorded in the absence and presence of Gd-DTPA (Fig. S6 A and B). The addition of Gd-DTPA caused considerable peak broadening, but had only marginal effects on peak positions. Fig. 7B shows the relative attenuation of the peak intensity along the sequence. Strikingly, these values correlate precisely with the calculated depth of the Ca atoms within the context of the filament (Fig. 7C), supporting the accuracy of the structure. In contrast, the same calculations for monomeric MAVSCARD and for the structure of Xu et al. (PDB ID code 3J6C) (5) differ drastically from our experimental PRE data (Fig. S6C). To identify residues that become buried in the filament core compared with the monomeric structure, we analyzed the Ca and Cb chemical shift changes between the monomeric MAVSCARD mutant D23S E26S in solution and the MAVSCARD filament measured at the same buffer conditions. (Fig. 7 A and D). A representation of the residues affected by either PRE or by chemical shift perturbation on the protomer structure of MAVSCARD shows that the data are perfectly complementary (Fig. 7 D and E). These experiments can thus be taken as convincing independent confirmation of the calculated structure and the validity of our approach.

Fig. 7.

Orientation of the MAVSCARD protomer within the filament. (A) Sum of the absolute values of Ca and Cb chemical shift changes between monomeric MAVSCARD mutant D25S E28S and MAVSCARD filament. The sites of point mutants are marked (*). (B) Gd-DTPA–induced PRE peak intensity reduction plotted against the sequence. (C) The depth (Δ) of each Ca atom from the Gd-DTPA accessible surface of a MAVSCARD protomer in the filament. For purpose of comparison with the PRE peak intensities, the inverse of the depth (1/Δ) is shown. (D) Residues with chemical shift differences larger than 0.4 ppm are displayed on the surface of the MAVSCARD protomer structure in green. (E) Residues with a severe decrease of the peak volume (more than 50%) in the presence of Gd-DTPA are displayed on the surface of the MAVSCARD protomer structure in blue.

Assembly Mechanism of MAVSCARD Filaments.

The protomer structure of MAVSCARD filaments is virtually identical to the solution NMR and crystal structures of the monomeric form, with backbone RMSD values of 2.37 and 1.82 Å, respectively (Figs. S1G and S3 D and F). This observation suggests that MAVSCARD monomers assemble into filaments by a rigid-body docking mechanism. The largest deviations occur in helix α3, which is deeply buried in the filament structure and contributes to both type I and type III interfaces. Residues at the N-terminus of α3 contribute most to the uncertainty of the helical symmetry determination (Fig. S5) and exhibit lower-than-average signal to noise values in the CONCA spectrum (Fig. S5B), indicating increased local dynamics and/or chemical exchange due to its contribution to the protomer interfaces. Among known death domain assemblies, the pyrin domains of ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD) and AIM2 (absent in melanoma 2) form helical structures with a similar orientational change of the helix2-helix3 loop and helix α3, suggesting that such a conformational change might facilitate the formation of the helical assembly and contribute to their plasticity (2, 38). Notably, one face of the cross section of a MAVSCARD filament is highly positively charged and the opposite one is mostly negatively charged (Fig. 5E), which supports our notion that the charge complementarity plays an important role in the filament assembly.

To gain additional insights into the assembly mechanism, we tested a number of single and double point mutants targeting each of the six interaction sites for their ability to form filaments at neutral pH. Gel filtration using Superdex 200 showed that filament formation was impaired for all these mutants. The double mutants D23S E25S, R64S R65S, and R37S R41S were completely monomeric (Fig. S6 D and E). Nevertheless, all mutants impaired the ability to activate the IFN-β signaling pathway (Fig. S6 F and G), suggesting these interfacial residues are crucial for MAVS functionality in vivo and further confirming the validity of our structure.

Discussion

We presented an efficient approach to determine the atomic resolution structure of a helical filament based exclusively on experimental ssNMR data without using any template or input from EM other than the information that the complex has a filamentous structure. We show that helical symmetry parameters can be faithfully determined from a set of interprotomer distance restraints with moderate levels of spectroscopic ambiguity. As these are essential for our approach, sparse isotope labeling was particularly useful as it yielded high-resolution spectra, which allowed a precise assignment within a narrow ±0.12-ppm tolerance window (Fig. 1C and Fig. S2). The presented approach is robust in the sense that it allows the unambiguous extraction of the helical handedness. The need to determine reliable helical symmetry parameters was highlighted by the recent dispute on the correct symmetry of MAVSCARD filaments analyzed by two different groups using cryo-EM (5–7).

Traditional approaches used for structure determination of proteins from NMR restraints often require the modeling of the entire molecular system with all degrees of freedom. Symmetric complex structure minimization by docking is a practical alternative but usually requires the number of subunits to be known, and an unambiguous assignment of the interprotomer restraints to specific pairs of protomers. This approach was mainly demonstrated for homo-oligomers with point symmetry where only rotations are involved (39–41). Thus far, only few high-resolution structures of helical assemblies from NMR data have been published (9–14). These structures were mostly cross–β-sheet amyloid fibrils, which constitute a particular case because protomers are stacked on each other with a helical rise corresponding to the hydrogen-bond length between β-strands of neighboring subunits (12, 42, 43). The only filamentous structures with more complex symmetries solved by ssNMR thus far are the type III secretion system needle and the M13 bacteriophage capsid that were determined using Rosetta-based approaches in combination with EM or fiber diffraction data (15, 16, 44). The Rosetta approach for oligomers combines efficient sampling of the conformational space with a physical all-atom force field that can possibly dominate over experimental input restraints (39, 45). In our approach to determine the helical symmetries, we intentionally used a simplistic force field commonly used for NMR structure determination (46). This choice ensures that the calculated oligomeric structures are predominantly the result of the experimental data, as this force field cannot effectively assess the correctness of structures by itself, and structure calculation thus relies on the input ssNMR restraints as the only attractive forces. However, this required the implementation of an efficient strategy to objectively evaluate and refine the set of NMR-derived restraints. We thus adapted the well-established ARIA approach to iteratively reassign intra- and interprotomer restraints within the context of the predetermined helical symmetry.

Additionally, our three-step strategy aims at disentangling the double problem of simultaneously finding the correct fold of the protomer and the correct arrangement of protomers. The strategy we implemented is completely automatable, which is advantageous to reduce user intervention and to ensure the objectivity and reproducibly of the calculation.

Despite their obvious significance, molecular structures of high-molecular-weight machineries are still scarce. We demonstrated an efficient ssNMR-based approach to derive not only atomic resolution structural restraints required for highest resolution structures but also the correct symmetry parameters with high fidelity. ssNMR allows for a straightforward structure validation by independent experiments such as solvent paramagnetic resonance enhancement. Our approach does not require any prior structural knowledge of the system and can be easily extended to other types of symmetry. In addition, structural information from other techniques could be efficiently implemented, thus enabling a combination of benefits from different experimental and computational techniques toward integrative approaches.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

Protein expression and purification was performed as described previously (23). For solution NMR measurements, samples containing 300 µM protein were kept in 50 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM DTT, pH 3, buffer with 0.01% NaN3. Sparse labeling with [1 or 2-13C] Glc was achieved by using [1-13C] Glc or [2-13C] Glc with 15N-labeled ammonium chloride as the sole 13C or 15N source in the growth medium. A diluted sample was prepared at pH 3 by mixing of unlabeled monomeric MAVSCARD with monomeric uniformly 15N-13C labeled MAVSCARD at a molar ratio of 6:1. Then the pH of the buffer was brought back to 7 to reassemble MAVSCARD into filaments. The [1/2-13C] Glc mixed sample was prepared in the same way by mixing [1-13C] Glc labeled protein with [2-13C] Glc labeled protein at an equimolar ratio. Approximately 15 mg MAVSCARD filament were packed into a 3.2-mm thin-wall NMR rotor by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 15 h using a specially designed filling device (47). To probe the solvent-accessible surface of the MAVSCARD filament, 10 mL MAVSCARD filaments (1.5 mg/mL) was incubated overnight with 100 mM Gd-DTPA and then ultracentrifuged into an ssNMR rotor at 100,000 × g for 15 h.

ssNMR Spectroscopy and Data Processing.

All NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance III 600-MHz spectrometer operating at a static field of 14.1 T equipped with a standard 3.2-mm Bruker triple-resonance MAS probe. All spectra were recorded at a sample temperature of 5 ± 1 °C. 15N and 13C transfer was established through band-selective cross-polarization, and SPINAL64 decoupling of 90 kHz was used during direct and indirect chemical shift evolution. Details of experimental parameters are described in Table S2. Chemical shift assignment was achieved in a previously described protocol with Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) code 25076 (23). To collect distance restraints, homonuclear 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra with DARR and PDSD were recorded on uniformly 15N-13C labeled, diluted and [1-13C] Glc, [2-13C] Glc sparsely labeled samples with a series of mixing times from 15 to 1,000 ms. PAIN-CP spectra were recorded on [1-13C] Glc-15N and [2-13C] Glc-15N labeled samples as previously described (48). To probe the solvent-accessible surface of the MAVSCARD filament, 13C-13C DARR spectra and 15N-13C NCA spectra of MAVSCARD filament were recorded in the absence and presence of 100 mM Gd-DTPA. All spectra were processed using Topspin 3.2 (Bruker Biospin) by applying squared sine bell shifted by 60° before zero filling and Fourier transformation. Polynomial baseline correction was used for both dimensions. The white noise level was calculated for all spectra as the mean root square of intensity over a wide spectral region depleted of any signal due to protein or possible spinning side band. We used an in-house written LUA script within the CARA environment to perform these calculations and mapped the obtained levels to CcpNmr for subsequent steps. Integration of peak intensities for PRE and other spectral analyses, peak picking, and assignments were performed using the CcpNmr software package (49). Peak integration was carried out in CcpNmr using the box sum volume method.

Assignment of Distance Restraints and Handling of Chemical Shift Ambiguities.

Peaks were picked automatically using a threshold of 4.7 times white noise level for all spectra. Peaks corresponding to artifacts such as spinning side bands were discarded. The isotopic labeling pattern present in the [1-13C]Glc and [2-13C]Glc-labeled samples was determined experimentally on the basis of 13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra recorded on monomeric MAVSCARD at pH 3, because we observed significant scrambling compared with the published basic labeling pattern. Intraresidual and sequential, as well as some medium-range, cross-peaks (between residues j and k, 2<|j–k|<4) were assigned from a series of short mixing time DARR spectra (50–250 ms) and from long mixing (250 ms) 3D NCACX and NCOCX spectra. Cross-peaks were considered as unambiguous if no other assignment options existed within a ±0.21-ppm tolerance window or if supported by an extensive network of other cross-peaks. The tolerance windows for the frequency-unambiguous assignment of cross-peaks were determined separately for uniformly and sparsely labeled samples. In both cases, we first determined the average resonance frequency and the respective chemical shift deviation for each nucleus from the intraresidual and sequential cross-peaks, averaged over all available spectra. The chemical shift deviations were less than 0.04 ppm for sparsely labeled samples and ∼0.07 ppm for uniformly labeled samples. For the manual assignment of frequency-unambiguous distance restraints, we thus chose tolerance windows of ±0.12 and ±0.21 ppm, respectively. Frequency-unambiguous long-range distance restraints were only assigned when supported in the spectra of sparsely labeled samples due to their improved resolution (Figs. 1 and 2 and Fig. S2). Additional short- and medium-range and all long-range intraprotomer distance restraints were assigned in the PDSD and PAIN spectra of [1-13C]Glc and [2-13C]Glc labeled sample based on the following criteria: (i) the cross-peaks must also be present in the 400-ms DARR spectrum of the [UL-13C6]Glc 1:6 diluted sample; (ii) the cross-peak is defined as frequency-unambiguous if no other assignment options exist within the tolerance window; and (iii) the cross-peak is classified as network-unambiguous only if no more than three assignment options exist within the tolerance window, the chemical-shift deviation of this assignment is significantly smaller than for the other possibilities (at least 0.06 ppm), and the assignment is supported by other cross-peaks (>3) (16). All other cross-peaks were considered as ambiguous. Interprotomer distance restraints were unambiguously assigned only if they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) absence in the spectrum of the [UL-13C6]Glc 1:6 diluted sample, or presence only in the spectrum of the mixed [(1/2)-13C]Glc-labeled sample compared with the spectra of the [1-13C] Glc or [2-13C] Glc samples (48) and (ii) frequency unambiguous assignment within a ±0.12-ppm tolerance window or network unambiguous; additional, optional criteria were (iii) at least two unambiguous cross-peaks for each pair of residues and (iv) cross-peak becomes frequency unambiguous in the PAIN spectra of [1-13C] Glc or [2-13C] Glc samples after all other intraprotomer assignment options were rejected in the protomer structure calculation.

Protomer Structure Calculation.

The structure of the MAVSCARD protomer (within the context of the filament) was calculated iteratively with ARIA 2.3 (28) and CNS software (33). Backbone dihedral angles were predicted with TALOS+ (25) from backbone chemical shifts, and predictions classified as “good” were converted into φ and ψ dihedral angle restraints. In addition, 86 hydrogen bonds, derived from TALOS+ secondary structure predictions, were introduced as distance restraints in the structure calculation. Both unambiguous and ambiguous distance restraints derived from ssNMR cross-peaks were applied with a flat-bottom harmonic potential using an upper bound of 8 Å. Structure calculation was performed using the following simulated annealing protocol: high-temperature sampling at 10,000 K (10,000 steps), the first annealing stage from 10,000 to 1,000 K (100,000 steps), and the second annealing stage from 1,000 to 50 K (60,000 steps). During the ARIA protocol, 60 conformers were calculated for the first eight iterations and 200 conformers were calculated in the final iteration. The 10 lowest energy structures were refined in a shell of water molecules. Table S3 provides a summary of ssNMR-derived restraints and statistics on the final ensemble of the protomer ssNMR structure.

Determination of the Helical Symmetry by Grid Search.

Helical screw symmetry is defined by the azimuthal rotation (or rotational twist θ) around the helical axis and the axial translation (or rise r) along the helical axis between two consecutive subunits in a given start (Fig. 4B). Our grid-search approach systematically calculates conformations of 1-start helical filaments for given sets of helical parameters (θ, r) and uses the 10 best conformers of the ssNMR protomer ensemble as initial coordinates. For each (θ, r), 100 conformers were calculated (10 per randomly positioned initial protomer structure) by applying protomer-ambiguous interprotomer ssNMR restraints using CNS (33). The helical symmetry was imposed by strict noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) constraints using 20 virtual copies of the central protomer (10 in each directions of the helical axis). The protocol to calculate a single helical conformation of 21 protomers consisted of (i) random positioning of the central protomer, (ii) a series of four rigid-body energy minimizations of 2,000 steps each, with decreasing values of force constant for the repulsive potential term (5.0–1.0), and (iii) 500 steps of flexible side chain minimization where backbone atoms were kept fixed. At each energy evaluation during minimizations, energetic contributions of interprotomer nonbonded interactions and distance restraints were computed by applying the helical symmetry operators (rotation of k*θ around and translation of k*r along the arbitrarily chosen helical axis for k in [−10,10]) to the coordinates of the central protomer (32). During the rigid-body minimizations, the central protomer had all degrees of freedom. The PARALLHDG 5.3 force field was used in conjunction with a single repulsion energy term using PROLSQ parameters for nonbonded interactions (46). Interprotomer distance restraints were applied using a soft-square potential with a scale of 50 kcal/mol/A2 and an upper limit of 8 Å. Because the symmetric copies of the central protomer were not modeled explicitly, interprotomer distance restraints were ambiguously applied between the central protomer (m) and its 20 symmetric copies (p) and averaged with “r6 summation” (50) using the following equation:

| [1] |

where da,m,p is the distance between a pair of atoms in protomers m and p corresponding to the ath assignment possibility of an interprotomer restraint. n-start helical conformations with cyclic Cn symmetry (n strands with n-fold rotational symmetry) were modeled by supplementing the set of helical strict NCS constraints with the appropriate rotational operators around the fixed helical axis (n − 1 rotations of 360°/n). The choice of the helical rotational axis has no influence on the outcome of the calculation because the modeled protomer is free to rotate and translate in all directions. The 2D grid-search was performed by repeating the protocol described above for all combinations of (θ,r) in the defined ranges and using increments of δθ for the twist angle and δr for the rise. Then, for each pair of (θ, r) explored in the grid, the median () of the total energy of the 20 lowest-energy helical conformers (among 100) was computed, and values were smoothened by averaging the grid with a sliding square window of size (3δθ, 3δr). Such smoothing was intended to correct for unexplored (θ, r) due to the resolution of the grid (size of the increments δθ, δr). Because the calculation of all individual helical conformations in the grid was independent from the others, the computational time can be greatly reduced by parallelizing the grid and dispatching the calculations on a computer cluster. To determine the helical parameters of MAVSCARD filaments using ambiguous interprotomer distance restraints, a coarse-grained grid-search was first performed using increments of δθ = 2° for the twist and δr = 0.2 Å for the rise and modeling of 1-start left-handed, 1-start right-handed and 3-start C3 helices. To further refine the symmetry parameters, a fine-grained grid-search was performed (δθ = 0.5° and δr = 0.1 Å) in a reduced range around the solution found with the coarse-grained search (left-handed, 100.0 ± 5.0° and 5.5 ± 1.5 Å). This fine-grained search yielded a minimum for θmin = 101° and rmin = 5.1 Å, values that were not explored in the coarse-grained search due to larger increments. Finally, a superfine-grained grid was computed using the final MAVSCARD protomer structure as starting conformation and the protomer-unambiguous interprotomer distance restraints determined by ARIA. While using very small increments, the superfine-grained grid-search converged to the same symmetry parameters as the fine-grained search, thus confirming the accuracy of the grid-search approach. Details (θ and r ranges, increments, and computational times) for the coarse-, fine-, and superfine-grained grid-search are given in Table S4.

Validation of the Grid-Search Approach.

A second coarse-grained search was performed using the 10 best conformers of the monomeric MAVSCARD solution NMR ensemble as initial structures of the protomer. Using the same protocol, interprotomer restraints, and search criteria as previously described for the coarse-grained grid-search (helix type, twist/rise ranges, and increments), the absolute grid minimum was obtained for a left-handed helix with θmin = 102° and rmin = 5.6 Å (the next minimum being θ = 102° and r = 5.4 Å; Fig. S4 A and B).

We further tested the grid-search methodology on a different helical assembly solved by ssNMR: the type III secretion system needle of Salmonella typhimurium (15). The initial atomic coordinates of the PrgL protomer structure and 162 interprotomer distance restraints were taken from PDB ID code 2LPZ (6). Helical symmetry was modeled using 30 copies of the central protomer (15 in both directions of the helical axis), and both left- and right-handed helices were tested. The grid ranges were set to [0°, 180°] for θ and [2.0 Å, 8.0 Å] for r using increments δθ = 2° and δr = 0.2 Å. The inner and outer diameters were restrained by imposing flat-bottom harmonic distance restraint between the Ca atoms of the PrgL protomer and the helical axis (lower bound of 12.5 Å and upper bound of 45 Å). The absolute grid minimum was obtained for a right-handed helix with θmin = 64° and rmin = 4.4 Å (the second minimum being θ = 64° and r = 4.2 Å; Fig. S4 C and D).

Helical Filament Structure Calculation with ARIA.

The helical structure of MAVSCARD was automatically calculated with ARIA 2.3/CNS 1.2 (28, 33). The standard ARIA calculation protocols and CNS routines were modified to fix the helical symmetry during the simulated-annealing (SA) stage with the same constraint used in the grid search and described elsewhere (32, 51). The helical symmetry of the filament was modeled with a total of 11 protomers (five copies of the central protomer in both directions of the helical axis). The symmetry parameters imposing the helical symmetry were the ones obtained by the fine-grained grid-search (θ = 101° and r = 5.1 Å). Input distance restraints were (i) the refined set of intraprotomer restraints obtained by ARIA for the calculation of the protomer structure and (ii) protomer-ambiguous interprotomer restraints (not assigned to specific protomers). Assignment of protomer-ambiguous interprotomer distance restraints was performed using the atomic coordinates of the central protomer (M) and its six closest symmetric neighbors, corresponding to protomers M − 4, M − 3, M − 1, M + 1, M + 3, and M + 4. The threshold for considering a restraint as violated was set to 0.1 Å, whereas the ambiguity cutoff for filtering unlikely assignment possibilities was set to 0.8. In addition to the ssNMR distance restraints, the backbone dihedral angle and hydrogen-bond restraints used for the calculation of the protomer structure were also applied. To ensure convergence of the calculation, the total number of steps in the cooling stage of the simulated annealing was increased to 140,000, and 500 conformers were generated per iterations (of which the 15 lowest energy ones were analyzed). All other ARIA parameters were set to their default values. Convergence was reached after two iterations. ARIA automatically removed three interprotomer restraints and the number of unambiguous intraprotomer restraints increased. Statistics on the ssNMR filament structure are given in Table S3 and Fig. S3B.

Code Availability.

An archive containing scripts and data for grid-search and ARIA calculations with helical symmetry may be downloaded at aria.pasteur.fr/supplementary-data/helical-ARIA.

Accession Codes.

The solution state NMR structure of monomeric MAVSCARD has been deposited under PDB ID code 2MS8. Chemical shift and restraint lists were deposited in BMRB under entry 25109. The ssNMR structure of the MAVSCARD filament has been deposited under PDB ID code 2MS7. Chemical shift and restraint lists were deposited in BMRB under entry 25076.

SI Materials and Methods

Negative Stain Electron Microscopy.

Negative stain sample preparation, according to Valentine et al. (52), was applied to visualize purified MAVS by means of medium-dose energy-filter transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM). Formation of protein filaments and sample homogeneity were thus checked. Working solutions of 100 µg/mL protein concentration were used to adsorb filaments to a 40-nm ultra-thin carbon foil by floating partially from a 1-mm2 carbon-coated piece of mica for 30 s at ambient temperature. After blotting with filter paper (Schleicher-Schuell), the carbon foil was transferred shortly to saturated uranyl acetate solute, pH 4.0, and was picked up with a reticulum foil-coated 300-mesh copper grid. The stain bulk was blotted and finally air dried. Ultrastructural analysis of negatively stained molecules was performed with an EF-TEM (Libra 120 plus; Zeiss), equipped with a bottom-mount cooled 2,048 × 2,048 CCD camera (SharpEye; Tröndle). Elastic brightfield images, free from electron energy loss and objective astigmatism (energy-slit width: 10 eV; objective aperture: 60 µm; beam current: 2 µA; acceleration voltage: 120 kV), were recorded at ×40,000 and/or ×50,000 magnification under close to low-dose conditions within the range of Gaussian and Scherzer focus (150–250 nm under focus).

Functionality Assay of the in Vitro-Expressed MAVSCARD.

National Institutes of Health 3T3 IFN-β-tGFP cells (kindly provided by Mario Köster, HZI Braunschweig, Germany) were cultured as a monolayer in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 400 µg/mL G418. At 80% confluence, cells are digested and resuspended in PBS to 5 × 106 cells/mL. Eight hundred microliters of the cell suspension was transferred into a 0.4-cm electroporation cuvette, with MAVSCARD filament or control protein at final concentration 100 µg/mL after removing the endodoxin. Cells were electroporated with 0.3 kV and 125-μF capacitance using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser. The time constant should be between 12 and 22 ms under this condition. The cell suspensions were then transferred to a flask containing prewarmed medium. The fluorescence of tGFP was detected by fluorescence microscopy 16 h after electroporation, and the population of GFP-positive cells was quantified by flow cytometry.

Solution NMR Spectroscopy.

All spectra were collected at 298 K using Bruker Avance III 600- or 700-MHz NMR spectrometers, both equipped with cryo-probes. For backbone and side chain assignment, a series of 2D 15N-HSQC, 13C-HSQC experiments and 3D HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HHN-Total Correlation Spectroscopy (TOCSY) (60 ms), and HHC-TOCSY (60 ms) experiments were acquired. An HH13C-Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement Spectroscopy (NOESY)-HSQC (80 ms) spectrum was acquired for aromatic side chain assignment. For distance restraints aliphatic HH13C-NOESY (80 ms), aromatic HH13C-NOESY (80 ms) and HH15N-NOESY (80 ms) spectra were recorded. Data were processed with Prosa (53) and analyzed with CARA (cara.nmr.ch/) (54). For measurements of relaxation parameters of 15N, conventional R1, R2, and 1H-15N NOE relaxation spectra were acquired using standard approaches (55). To determine the spin-spin relaxation constant R2, experiments were recorded with delays of 17, 34, 51, 85, 119, 153, 187, 237, 288, and 356 ms. To determine the R1 relaxation constant, delays of 10, 30, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 800, 1,000, and 1,200 ms were applied. The detailed acquisition parameters for solution NMR are listed in Table S1. The relaxation rates and the experimental errors were calculated by following the decay of the height of each 1H-15N peak from a series of spectra using a build-in option in the CcpNmr software package (49).

Structure Calculation of Monomeric MAVSCARD by Solution NMR.