Abstract

Background:

This study was to examine the expression of total vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the anti-angiogenic VEGF165b isoform in the vitreous body of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) patients, and to further study the role of the VEGF splicing in the development of ROP.

Methods:

This was a prospective clinical laboratory investigation study. All patients enrolled received standard ophthalmic examination with stage 4 ROP that required vitrectomy to collect the vitreous samples. The control samples were from congenital cataract patients. The expression of total VEGF and the anti-angiogenic VEGF165b were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results were analyzed statistically using nonparametric tests.

Results:

The total VEGF level was markedly elevated in ROP samples while VEGF165b was markedly decreased compared to control group. The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform was significantly decreased in ROP patients which were correlated with the ischemia-induced neovascularization.

Conclusions:

There was a switch of VEGF splicing from anti-angiogenic to pro-angiogenic family in ROP patients. A specific inhibitor that more selectively targets VEGF165and controls the VEGF splicing between pro- and anti-angiogenic families might be a more effective therapy for ROP.

Keywords: Neovascularization, Retinopathy of Prematurity, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, VEGFxxx, VEGFxxxb

INTRODUCTION

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) has become one major cause of visual loss in children recently. The normal retinal vessel development was suppressed in ROP, which could lead to an ischemia-induced neovascularization and proliferative retinopathy.[1]

Neovascularization is one of the major pathological changes in ROP patients which is a complex process mediated by various factors including vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A, hereinafter referred to as VEGF). VEGF is the dominant pro-angiogenic factor that could increase the abnormal vascular permeability and finally lead to retinal neovascularization following with vitreous hemorrhage, traction retinal detachment, and loss of vision.[2]

It has been identified that actually VEGF was differentially spliced from exons 8 to form two opposite-functioned VEGF families: The pro-angiogenic VEGFxxx family and the anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb family (xxx represents the number of amino acids of the secreted isoform). The VEGFxxxb family had the same length as VEGFxxx family, but with different C-terminal amino acid sequences.[3,4,5] Some studies found that both two VEGF isoforms expressed in human eyes while VEGFxxxb isoforms were the most abundant species in normal vitreous.[3,6,7]

VEGF165b was the first member identified. VEGF165b could also bind to VEGFR2 (KDR/FLK1), but without activating downstream angiogenesis signaling. Previous studies showed that VEGF165b was downregulated in angiogenic diseases such as diabetic retinopathy,[4,8] retinal vein occlusion, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD).[9,10] However, VEGF165b was up-regulated in nonangiogenic diseases such as glaucoma[11] and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[12]

In our previous studies, we have illustrated the neovascularization may depend on the imbalance of the two VEGF isoforms in a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR). However, the VEGF165b protein expression in the vitreous of ROP patients has not been investigated previously. We sought to determine the expression pattern of VEGF165b and the relative expression of the anti-angiogenic isoforms in the vitreous sample of ROP patients to further study the role of the VEGF splicing in the development of ROP.

METHODS

Patients

Our prospective study was performed with the approval of the Ethical Committee of Peking University People's Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

All patients were enrolled and provided their written informed consents between July 2013 and December 2013.

This prospective series included 20 vitreous samples from 17 patients with ROP stage 4 who had received vitreous aspiration during vitrectomy surgery. Samples from five patients with congenital cataract were selected as a control group.

All patients with stage 4 ROP received a standard ophthalmic examination by retinal specialist (Dr. Jianhong Liang and Dr. Hong Yin) under anesthesia by indirect ophthalmoscopy and a RetCam 120 digital fundus camera (Massie Research Laboratories, Inc., USA).

Infants with stage 4 ROP after peripheral laser treatment were enrolled. Twenty eyes of 17 infants (10 male and 7 female) were included. The stages of ROP were classified according to the International Classification of ROP.

Vitreous was collected from the eyes of stage 4 ROP patients who underwent vitrectomy. The control group vitreous samples was collected from 5 eyes underwent surgery for congenital cataract. The control group patients were all full-term babies without any systemic, inherited, or metabolic disorders.

Sample collection

All patients underwent vitrectomy surgery performed by Dr. Jianhong Liang and Dr. Hong Yin at the Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing, China, after approval by the hospital's institutional review board.

Undiluted vitrectomy samples were obtained from the mid vitreous of children with stage 4 ROP using a 3-port lens-sparing vitrectomy with manual suction by sterile syringes. Approximately 100 μl undiluted vitrectomy samples were obtained from the mid vitreous of patients. The intraocular irrigating solution (Alcon) was not opened until the procedure completed.

In the control group (congenital cataract), anterior vitrectomy approach was used after the phacoemulsification. The undiluted vitreous samples were also aspirated by sterile syringes.

The undiluted vitreous samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to remove cells and debris, then immediately transferred to store at −80°C until the time of assay. The technician and doctor involved in the study were masked to all the samples.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Total VEGF and VEGF165b were measured in vitreous samples by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a kit for human anti-VEGF (all isoforms) (Duoset VEGF ELISA DY-293; R and D Systems) and a kit for human VEGF165b (Duoset VEGF ELISA DY3045; R and D Systems).

Each assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instruction for the VEGF and VEGF165b ELISA. The optical density was determined at 450 nm using an absorption spectrophotometer. The optical density mean values were reading for three times for quantitative analysis.

A standard curve for this assay was built with recombinant human VEGF and VEGF165b (R and D Systems).

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed statistically using nonparametric tests because of the skewed distribution (Kruskal–Wallis variance analysis and Bonferroni corrected Mann–Whitney U-test) and were expressed as the median and range. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

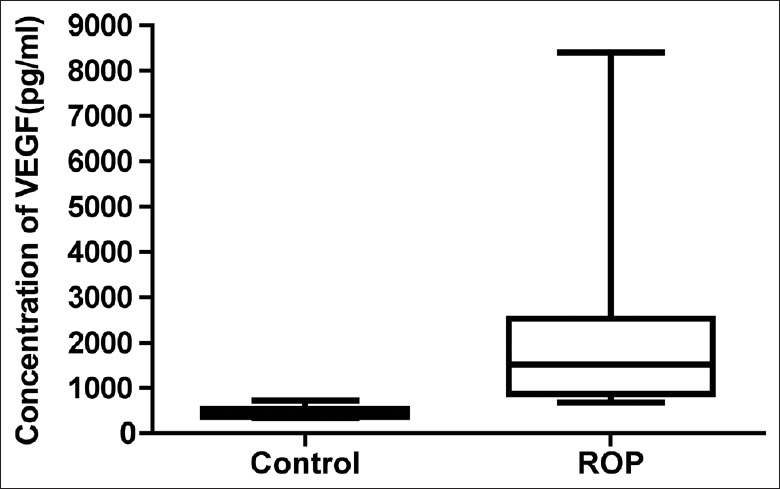

Total vascular endothelial growth factor levels were markedly elevated in the retinopathy of prematurity patients’ vitreous samples

The concentrations of total VEGF in ROP patients and congenital cataract patients’ vitreous samples were measured by ELISA. Our results showed that the concentration of total VEGF was 467.2 ± 45.86 pg/ml (mean ± standard error of mean [SEM]) in the control group. However, the concentration of total VEGF was 2396 ± 695 pg/ml (mean ± SEM) in ROP vitreous samples which was markedly elevated when compared with control group [P < 0.01, Figure 1]. A 5.12-fold increase of total VEGF protein expression was detected in ROP patients’ vitreous body compared to control group.

Figure 1.

Total vascular endothelial growth factor levels elevated in the retinopathy of prematurity patients’ vitreous samples. The concentrations of total vascular endothelial growth factor in retinopathy of prematurity patients and congenital cataract patients’ vitreous samples were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

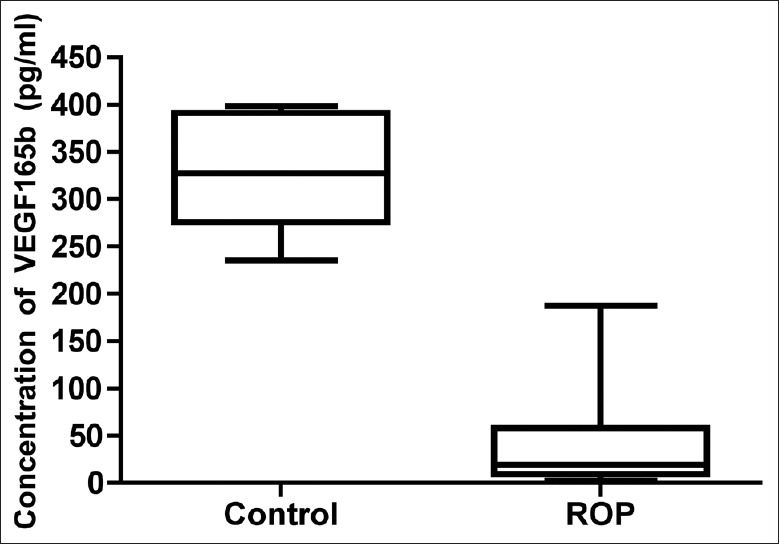

VEGF165b levels was markedly down regulated in the retinopathy of prematurity patients’ vitreous samples

The concentration of VEGF165b in ROP patients and congenital cataract patients’ vitreous samples were measured by ELISAs. Our results showed that the concentration of VEGF165b was 331.2 ± 23.63 pg/ml (mean ± SEM) in the control group. However, the concentration of VEGF165b was 51.32 ± 16.35 pg/ml (mean ± SEM) in ROP vitreous samples which was markedly decreased when compared with control group [P < 0.01, Figure 2]. A 6.45-fold down-regulation of the VEGF165b protein expression was detected in ROP patients’ vitreous body compared to control group.

Figure 2.

VEGF165b Levels down-regulated in the retinopathy of prematurity patients’ vitreous samples. The concentrations of VEGF165b in retinopathy of prematurity patients and congenital cataract patients’ vitreous samples were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

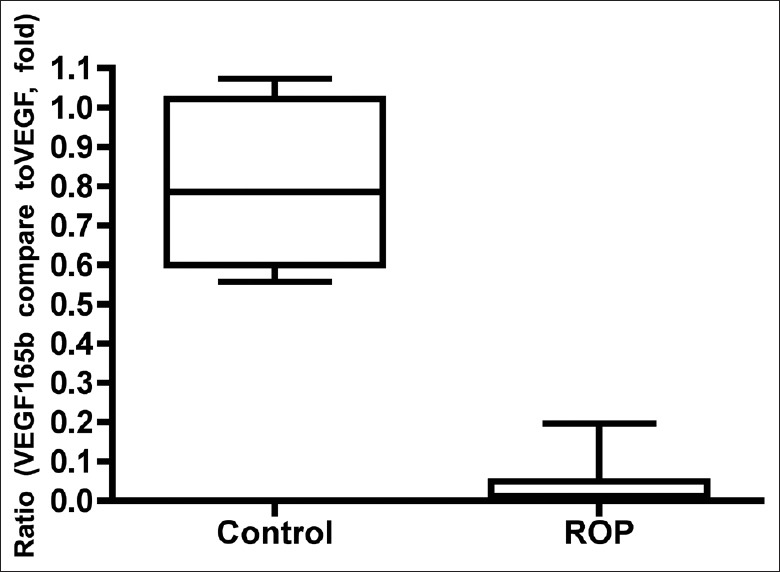

The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform decreased in retinopathy of prematurity patients

When analyzing the relative protein expression level of the VEGF165b isoform, the ratio of VEGF165b and total VEGF, it was much clearer to see the switch from anti-angiogenic isoform to pro-angiogenic isoform in ROP patients. The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform was significantly decreased in ROP group than in control group (P < 0.01) which was correlated with the ischemia-induced neovascularization in ROP patients [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform decreased in retinopathy of prematurity patients. The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform (the ratio of VEGF165b and total vascular endothelial growth factor) was significantly decreased in retinopathy of prematurity group than in control group (P < 0.01). Thus, there was a switch of vascular endothelial growth factor splicing from anti-angiogenic to pro-angiogenic family in retinopathy of prematurity patients.

DISCUSSION

The pathological process of ROP patients was divided into two phases: Phase I as the hyperoxic phase and phase II as the ischemic phase.[13] In the relatively hyperoxic phase I, the VEGF expression was downregulated. The normal retinal vessel growth was suppressed, and the vessels were constricted. In the hypoxia phase II, the ischemic retina produced angiogenic factors including VEGF, which further resulted in neovascularization.[14,15,16]

Neovascularization is one of the major pathological changes in ROP patients which is a complex process mediated by the imbalance of anti-angiogenic system and pro-angiogenic system. Among those, VEGF is the key factor for neovascularization. Our understanding of how neovascularization is regulated by VEGF requires a complete re-evaluation since the VEGF was differentially spliced into two opposite-functioned families.[3,4]

In our previous studies, we showed that the neovascularization may be related to the imbalance of the two VEGF isoforms in a mouse model of OIR.[17] However, the VEGF165b protein expression in ROP patients remains unknown. Here, for the first time, we investigated the expression of VEGF165b and the relative expression of the anti-angiogenic isoforms in the vitreous sample of ROP patients. From the data we described, it showed that the level of VEGF165b was significantly downregulated in ROP patients while the total VEGF level was significantly up regulated and overwhelmed the anti-angiogenic VEGF165b isoforms. When analyzing the relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform, it was much clearer to see the switch from anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform to pro-angiogenic VEGF isoform in ROP patients. The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform was significantly decreased in ROP group, which was correlated with the ischemia-induced neovascularization. Those results were corresponding with previous studies showing that VEGF165b was downregulated in angiogenic diseases such as diabetic retinopathy,[4,8] retinal vein occlusion and AMD patients.[9,10]

The mechanism for the switch of VEGF splicing from anti-angiogenic to pro-angiogenic family in ROP patients remains unknown. However, our results showed that the two VEGF families were not equally affected. The relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform was significantly down regulated while the total VEGF level was significantly up regulated. This suggested that the pro-angiogenic VEGF isoforms was the majority of the total VEGF and overwhelmed the anti-angiogenic VEGF isoforms along with the neovascularization development in ROP patients. Previous studies have investigated the splice site selection factors including insulin-like growth factor-1, which induced more VEGF165b and less VEGF165b expression. Other studies also showed that the splicing could be regulated by protein kinase C inhibition and SRPK1/2 inhibition.[18] Thus, we assumed that the regulation of alternative splicing could be a potential therapeutic strategy in ROP. Further studies focused on the alternative splicing regulation may provide new therapy for controlling neovascularization.

We have illustrated that the neovascularization development correlates with an increase of total VEGF isoforms and the decrease of VEGF165b, indicating that there is a pro-angiogenic VEGF shift in the neovascularization development in a mouse model previously.[17] In this study, we also noticed the same switch of VEGF splicing from anti-angiogenic to pro-angiogenic family in ROP patients.

In our study, we noticed that the range of total VEGF and VEGF165b varied form patient to patient, which may associate with the effect of anti-VEGF treatment and prognosis. Recent studies have showed that the resistance to anti-VEGF treatment may depend on the high level of VEGF165b expression in colon cancer.[19] Our previous study illustrated that the anti-angiogenic effectiveness of bevacizumab might depend on the relative high expression of VEGF165b after intravitreal bevacizumab injection in a mouse model of OIR.[20] However, there have been no studies to determine whether anti-VEGF therapy can affect the two VEGF isoforms equally in ROP patients which need to be verified in further studies. Considering the varied response to anti-VEGF therapy of ROP as well as AMD clinically, we assumed that anti-VEGF therapy could be more effective in those condition with majority of VEGFxxx expression, whereas being less effective in those condition with majority of VEGFxxxb expression.

In neovascular diseases such as exudative AMD and PDR, the release of VEGF is continuous.[21,22] However, there is only a single burst of VEGF release in ROP.[23] Anti-VEGF therapy would be a more effective treatment of ROP if it were delivered in the VEGFxxx dominated patients and VEGFxxx dominated disease stage which could rapidly switch the pro-and anti-angiogenic isoforms, but this needs to be further verified. Our further studies for the treatment in ROP patients should focus on the optimal timing for the therapy and the selection of the sensitive patients for the anti-VEGF therapy considering the switch of the two VEGF isoforms.

Furthermore, VEGFxxxb isoforms are not only competitive inhibitors, but also may play a physiological role in ROP patients. Thus, the preservation of the physiologic development of retina is equally important as the effectiveness on the pathologic neovascularization. Anti-VEGF therapy that more selectively targeted VEGF165by may be more effective. Previous studies concluded that VEGF165b increased the normal vessels area in mouse[24] and did not prevent physiological revascularization in the central ischemic retina.[25,26]

Taken together, our results suggested that the relative protein expression level of VEGF165b isoform was significantly decreased in ROP patients’ vitreous body which was correlated with the ischemia-induced neovascularization. There was a switch of VEGF splicing from anti-angiogenic to pro-angiogenic family in ROP patients. The role of VEGF splicing regulation plays a key role in the neovascularization in ROP. We believed that specific inhibitor that more selectively targets VEGF165 and controls the VEGF splicing between pro- and anti-angiogenic families might be a more effective therapy for ROP.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by a grant from Beijing Nova Program (Z131102000413004), National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2011CB510200) and Peking University People's Hospital Research and Development Funds (RDB2013-21, 2118000540).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yi Cui

REFERENCES

- 1.Terry TL. Fibroblastic overgrowth of persistent tunica vasculosa lentis in infants born prematurely: II. Report of cases-clinical aspects. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1942;40:262–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witmer AN, Vrensen GF, Van Noorden CJ, Schlingemann RO. Vascular endothelial growth factors and angiogenesis in eye disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, et al. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4123–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrin RM, Konopatskaya O, Qiu Y, Harper S, Bates DO, Churchill AJ. Diabetic retinopathy is associated with a switch in splicing from anti-to pro-angiogenic isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2422–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates DO, Mavrou A, Qiu Y, Carter JG, Hamdollah-Zadeh M, Barratt S, et al. Detection of VEGF-A (xxx) b isoforms in human tissues. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beazley-Long N, Hua J, Jehle T, Hulse RP, Dersch R, Lehrling C, et al. VEGF-A165b is an endogenous neuroprotective splice isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor A in vivo and in vitro . Am J Pathol. 2013;183:918–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Dou T, Liu C, Fu M, Huang Y, Gu S, et al. The evolution of alternative splicing exons in vascular endothelial growth factor A. Gene. 2011;487:143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter JG, Gammons MV, Damodaran G, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO. The carboxyl terminus of VEGF-A is a potential target for anti-angiogenic therapy. Angiogenesis. 2015;18:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s10456-014-9444-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baba T, Bikbova G, Kitahashi M, Yokouchi H, Oshitari T, Yamamoto S. Level of vascular endothelial growth factor 165b in human aqueous humor. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:830–6. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.877935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehlken C, Rennel ES, Michels D, Grundel B, Pielen A, Junker B, et al. Levels of VEGF but not VEGF (165b) are increased in the vitreous of patients with retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:298–303.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ergorul C, Ray A, Huang W, Darland D, Luo ZK, Grosskreutz CL. Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-A165b (VEGF-A165b) are elevated in experimental glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1517–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricker LJ, Dieudonné SC, Kessels AG, Rennel ES, Berendschot TT, Hendrikse F, et al. Antiangiogenic isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor predominate in subretinal fluid of patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Retina. 2012;32:54–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821800b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossi E, Koerner F. Retinopathy of prematurity. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:241–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01701481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alon T, Hemo I, Itin A, Pe’er J, Stone J, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nat Med. 1995;1:1024–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce EA, Foley ED, Smith LE. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by oxygen in a model of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1219–28. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140419009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone J, Itin A, Alon T, Pe’er J, Gnessin H, Chan-Ling T, et al. Development of retinal vasculature is mediated by hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression by neuroglia. J Neurosci. 1995;15(7 Pt 1):4738–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04738.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao M, Shi X, Liang J, Miao Y, Xie W, Zhang Y, et al. Expression of pro-and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF in the mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93:921–6. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nowak DG, Amin EM, Rennel ES, Hoareau-Aveilla C, Gammons M, Damodoran G, et al. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) splicing from pro-angiogenic to anti-angiogenic isoforms: A novel therapeutic strategy for angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5532–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolard J, Bevan HS, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Molecular diversity of VEGF-A as a regulator of its biological activity. Microcirculation. 2009;16:572–92. doi: 10.1080/10739680902997333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi X, Zhao M, Xie WK, Liang JH, Miao YF, DU W, et al. Inhibition of neovascularization and expression shift of pro-/anti-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms after intravitreal bevacizumab injection in oxygen-induced-retinopathy mouse model. Chin Med J. 2013;126:345–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik RA, Schofield IJ, Izzard A, Austin C, Bermann G, Heagerty AM. Effects of angiotensin type-1 receptor antagonism on small artery function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2005;45:264–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153305.50128.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grisanti S, Tatar O. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor and other endogenous interplayers in age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:372–90. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micieli JA, Surkont M, Smith AF. A systematic analysis of the off-label use of bevacizumab for severe retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:536–543.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnussen AL, Rennel ES, Hua J, Bevan HS, Beazley Long N, Lehrling C, et al. VEGF-A165b is cytoprotective and antiangiogenic in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4273–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, et al. VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: Mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7822–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rennel E, Waine E, Guan H, Schüler Y, Leenders W, Woolard J, et al. The endogenous anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform, VEGF165b inhibits human tumour growth in mice. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1250–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]