Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic inflammation and muscle aging are closely linked. Mitochondrial clearance is a process to dampen inflammation and is a critical pre-requisite to mitobiogenesis. The combined effect of aging and chronic inflammation on mitochondrial degradation by autophagy is understudied. In interleukin 10 null mouse (IL-10tm/tm), a rodent model of chronic inflammation, we studied the effects of aging and inflammation on mitochondrial clearance. We show that aging in IL-10tm/tm is associated with reduced skeletal muscle mitochondrial death signaling and altered formation of autophagosomes, compared to age-matched C57BL/6 controls. Moreover, skeletal muscles of old IL-10tm/tm mice have the highest levels of damaged mitochondria with disrupted mitochondrial ultrastructure and autophagosomes compared to all other groups. These observations highlight the interface between chronic inflammation and aging on altered mitochondrial biology in skeletal muscles.

Keywords: IL-10, Autophagy, Mitochondria, MIF, NIX

INTRODUCTION

The age-related inflammatory myopathies are strongly associated with mobility impairment, falls, and frailty (1–6). The mitochondria plays a central role in the muscle inflammatory aging process and serves as a link between aging and inflammation (7). Evidence suggests that changes in mitochondria are influenced by chronic inflammation, and as a result, the increased free radical production from dysfunctional mitochondria further activates inflammatory cascades thus creating a vicious cycle (8). The clearance of damaged mitochondria is therefore a critical step in breaking this cycle and is an important pre-requisite for the generation of new mitochondria (9). The impact of chronic inflammation on mitochondrial degradation and clearance by autophagy (mitophagy) is understudied in the context of aging and frailty.

Several factors mediate the interaction between inflammation and mitophagy. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine expressed in muscle fiber membranes (10). MIF has been shown to inhibit mitochondria-dependent death pathways (11) and prevent apoptosis. In contrast, Nix/Bnip3L (NIP3-like protein X, NIX) (12) is a mitochondrial death protein in that it triggers mitophagy and triggers apoptosis (13). NIX and MIF have been shown to functionally and physically antagonize each other (14). The combined effects of aging and chronic inflammation on NIX/MIF and subsequently on autophagy and mitochondrial clearance in skeletal muscles are not known. Here we sought to investigate the progression and development of age-related myopathies in the pre-existing context of inflammatory conditions. To model inflammation and to study the biology linking chronic inflammation, aging, and late-life myopathy, we utilized the B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn/J (IL-10tm/tm) mouse that is deficient for interleukin-10 (IL–10). The IL-10tm/tm mouse has a propensity to develop age-related elevated serum inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-a)), muscle weakness, and higher mortality compared to C57BL/6 (B6) controls (15;16). Our prior findings including abnormal mitochondrial energy production, ATP kinetics (17) and differential expression of apoptosis and mitochondrial function genes (15) in the skeletal muscles of old IL-10tm/tm mice suggest that mitochondria alterations may play an important role in linking chronic inflammation and myopathy. Given this evidence, we hypothesized that in the skeletal muscles of IL-10tm/tm mouse, disturbance in mitochondrial ATP kinetics is precipitated by inflammation and age-related changes in mitochondrial clearance. In order to test these hypotheses, we sought to identify in the quadriceps femoris muscles of IL-10tm/tm and B6 mice, inflammation- and age-associated differences in mitochondrial degradation biology using markers of mitophagy induction (NIX), microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 autophagosomes marker (LC3), apoptosis inhibition (MIF) (14;18;19), and changes in mitochondria ultrastructure using electron microscopy.

METHODS

Animals

Female IL-10tm/tm and B6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD) were housed in specific pathogen free barrier conditions until the appropriate age was reached and then sacrificed. A cross-sectional study design was utilized to compare differences in quadriceps femoris muscle (QF) gene expression and mitochondria ultrastructure between groups (N=3–6) of young (3–5 months-old) and old (22–24 months-old) mice. All protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Protein extraction/Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from flash frozen QF muscles using T-PER (Thermo Scientific) with the addition of protease (Complete Mini, Roche) and phosphatase (PhosStop, Roche) inhibitors. Equal concentrations of proteins were electrophoresed using Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: NIX (Invitrogen: 1:5,000 mouse primary, 1:10,000 goat secondary), LC3 (Cell Signaling: 1:1,000 mouse primary, 1:10,000 goat secondary), MIF (Santa Cruz: 1:500 rabbit primary, 1:5,000 goat secondary), and actin (Sigma: 1:10,000 rabbit primary, 1:20,000 goat secondary). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to detect bands (Amersham). Quantitative Western blot analyses were performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test or Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis with a Dunnett’s post-hoc test were used to determine differences among groups. When 2 groups were compared, an unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t-test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM was used to compare differences in mitochondrial ultrastructure and autophagosome (AP) accumulation. Data acquisition and analyses for TEM utilized multiple thin QF sections (70–90 nm) with high tissue integrity captured on representative photomicrographs (45 µm2 of muscle tissue/image) from 10 randomly selected fields (20). Mitochondria were identified as normal if intact, or abnormal if they had disrupted membranes, cristae depletion, and matrix dissolution (21;22). Group differences in the frequency of mitochondria with abnormal morphology were tested by chi-square. AP were quantified for each mouse by averaging the number of AP detected at 10,000× magnification per 32,000 µm2 of tissue from three distinct grids. Group differences in AP/32,000 µm2 were tested by repeated-measure ANOVA.

RESULTS

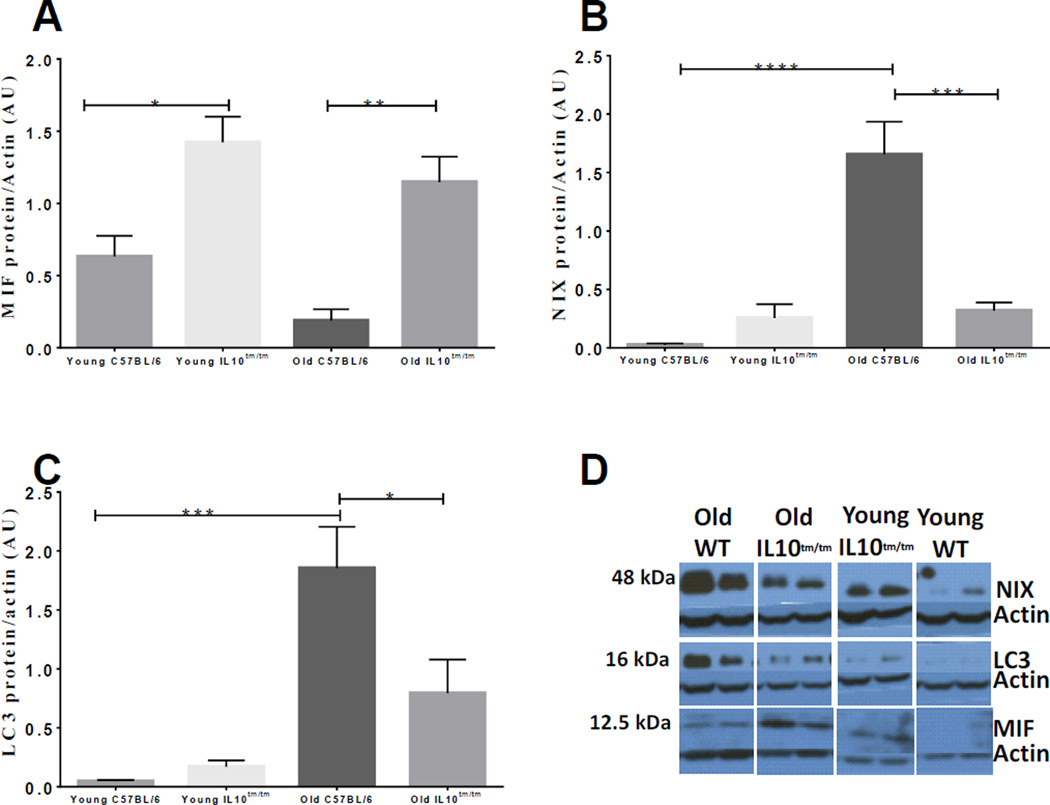

MIF is detected at higher levels in inflammatory myopathies and may function as a NIX antagonist to delay apoptosis by inhibiting mitochondria-dependent death pathway. In the IL-10tm/tm mouse, inflammation was associated with higher levels of skeletal muscle MIF proteins (young B6, 0.6 ± 0.1 AU vs. young IL-10tm/tm, 1.4 ± 0.2 AU, P<0.05; and old B6, 0.2 ± 0.1 AU vs. old IL-10tm/tm, 1.1 ± 0.2 AU, P<0.01; Fig 1A). Given the antagonistic crosstalk between MIF and NIX on mitochondrial homeostasis, we quantified changes in NIX protein levels in skeletal muscles of our mouse cohorts. In contrast to MIF, the expression of NIX was highest in the skeletal muscles of the old control mice (young B6, 0.03 ± 0.01 AU vs. old B6, 1.7 ± 0.3 AU, P<0.0001; Fig 1B). Interestingly, in old IL-10 tm/tm mice that exhibited combined effects of aging and inflammation, the expression of NIX was lower compared to the old control mice (old IL-10tm/tm, 0.3 ± 0.08 AU vs. old B6, 1.7 ± 0.3 AU, P<0.001; Fig 1B).

Fig 1. Aged and inflamed skeletal muscles show changes in MIF, NIX, and LC3 expression.

Western blot analyses of skeletal muscle protein extracts using antibodies against (A) MIF, (B) NIX, and (C) LC3. Actin was used as a loading control. Relative expression was calculated in arbitrary units (AU). (D) A representation of the MIF, NIX, and LC3 Western blots. Data are means ± SEM (n=3–5 animals) *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

In order to determine if NIX and MIF expression in the different animal groups resulted in changes in assembly of autophagosomes (AP), we quantified changes in LC3 expression. Parallel to NIX levels, the highest expression of LC3 was seen in the old control group as compared to all the other groups (old B6, 1.9 ± 0.4 AU vs. old IL-10tm/tm, 0.8 ± 0.3 AU, P<0.05; Fig 1C). Taken together, these data suggest that inflammation- and age-associated differences in NIX, MIF and LC3 expression are particularly pronounced in old IL-10tm/tm mice and that these changes may influence mitochondrial autophagy.

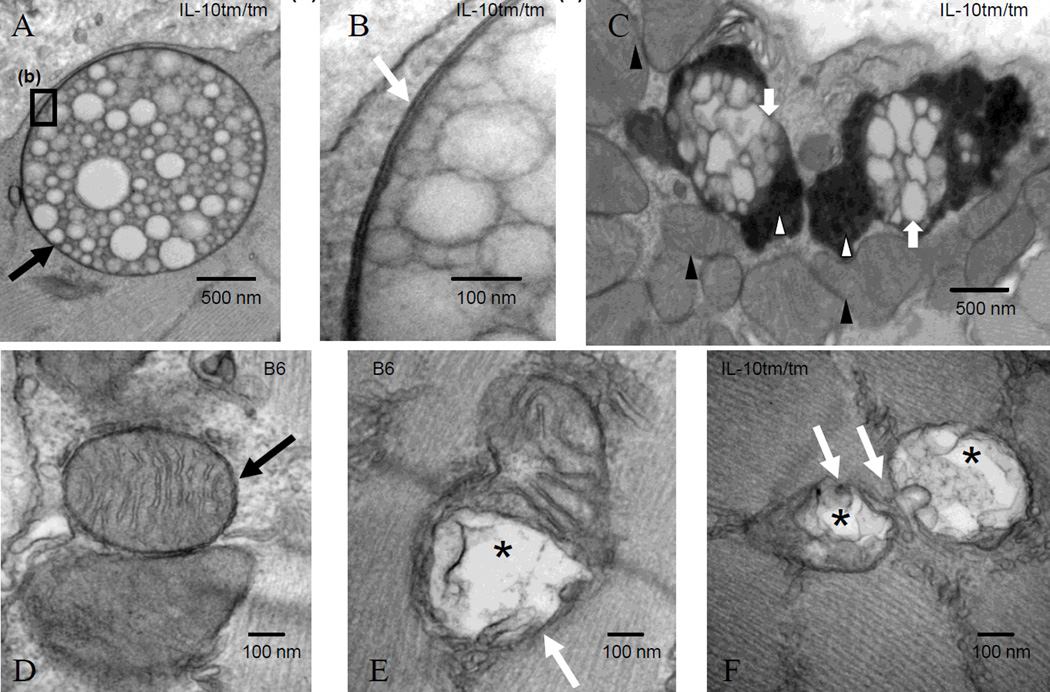

Parallel to MIF, NIX, and LC3 gene expression changes, more intracellular double-membrane vacuolated structures consistent with AP (Fig 2A, 2B) were identified in old IL-10tm/tm compared to old B6 (12.7 ± 4.8 AP/32,000 µm2 vs. 8.3 ± 3.2 AP/32,000 µm2, p=0.03; Table 1) on TEM. AP frequently localized to clusters of mitochondria (89.5% in old IL-10tm/tm, 88.1% in old B6; Fig 2C). Some AP appeared to contain predominately lipids (Fig 2A, 2B), while most others appeared to contain mixed cellular contents and electron-dense lipofuscin-like granules (Fig 2C) (25, 26). Old IL-10tm/tm had more AP with granular inclusions compared to old B6 (35.6% vs. 23.2%, p<0.015 by chi-square). Normal (Fig 2D) and abnormal, likely depolarized (Fig 2E, 2F) mitochondria were present in all mice groups but the frequency of mitochondria with abnormal ultrastructure was higher in old IL-10tm/tm (7.55% in young IL-10tm/tm vs. 14.21% in old IL-10tm/tm, p<0.001) and old B6 (4.88% in young B6 vs. 7.63% in old B6, p=0.012; Table 1). IL-10tm/tm had significantly more abnormal appearing mitochondria compared to B6 of both age groups (Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest inflammation- and age-associated differences in mitochondrial damage and clearance and mitochondrial autophagy in skeletal muscles of mice.

Fig 2.

Altered mitochondrial ultrastructure and autophagosomes with aging and/or inflammation. TEM assessment of autophagosomes (AP) and mitochondrial morphology in quadriceps femoris muscles of female IL-10tm/tm and B6 mice. (A) Photomicrograph demonstrating the presence of an intracellular, vacuolated, double-membrane AP (black arrow, 30,000×) in a longitudinal skeletal muscle section of a 23 months-old IL-10tm/tm mouse. (B) Double-membrane structure (white arrow, 200,000×) surrounding an AP. (C) AP with electron-dense granular inclusions (white arrow heads, 25,000×) located in proximity of clusters of mitochondria (black arrow heads). (D) Mitochondria with normal ultrastructure including intact mitochondrial membranes, cristae, and matrix (black arrow, 80,000×) in the skeletal muscle of a 23 months-old B6 mouse. (E, F) Mitochondria with abnormal structure including disrupted membrane (white arrows), loss of cristae, and matrix dissolution (asterisks) in 23 months-old B6 (E, 100,000×) and IL-10tm/tm (F, 80,000×) mice.

Table 1.

Autophagosome (AP) quantification and mitochondria morphology in quadriceps femoris muscles demonstrating an age and genotype effect.

| Genotype and Age | Mitochondria Morphology | Comparison p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Abnormal | Percent Abnormal |

IL-10tm/tm 3 months-old |

IL-10tm/tm 23 months-old |

B6 3 months-old |

B6 23 months-old |

|

| IL-10tm/tm 3 months-old | 784 | 64 | 7.55 | _ | |||

| IL-10tm/tm 23 months-old | 1,098 | 182 | 14.21 | <0.001* | _ | ||

| B6 3 months-old | 799 | 41 | 4.88 | 0.03* | <0.001* | _ | |

| B6 23 months-old | 1,476 | 122 | 7.63 | _ | <0.001* | 0.012* | _ |

| Autophagosomes per 32,000 µm2 |

IL-10tm/tm 3 months-old |

IL-10tm/tm 23 months-old |

B6 3 months-old |

B6 23 months-old |

|||

| IL-10tm/tm 3 months-old | 0 | _ | |||||

| IL-10tm/tm 23 months-old | 12.7 ± 4.8 | <0.001* | _ | ||||

| B6 3 months-old | 0 | _ | <0.001* | _ | |||

| B6 23 months-old | 8.3 ± 3.2 | <0.001* | 0.03* | <0.001* | _ | ||

Asterisks indicate statistically significant p values. Sample size was 4 for 3 months-old B6 and IL-10tm/tm and 6 for 23 months-old B6 and IL-10tm/tm mice.

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that in the skeletal muscles of IL-10tm/tm and B6 mice, there are inflammation- and age-associated changes in mitochondrial biology including mitochondrial ultrastructure (abnormal appearing mitochondria), mitophagy induction (NIX, AP and LC3), and mitochondria-dependent death pathway inhibition (MIF). In old IL-10tm/tm mice compared to age-matched B6 controls, these mitochondria-related changes are particularly enhanced, suggesting that inflammation and aging have an additive role in altered mitochondrial biology in skeletal muscles.

The pathogenesis of sarcopenia likely involves a number of intramuscular specific processes including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired mitochondrial turnover, and mitochondrion-mediated apoptosis (23). In this study, we focused on the process of mitophagy (autophagy-mediated mitochondrial turnover) in skeletal muscles. Many studies have demonstrated aging-associated progressive accumulation of damaged macromolecule and organelle and alteration in mitophagy (24–30). Consistent with the literature, our TEM observations support the notion that aging itself is associated with progressive accumulation of damaged mitochondria and alteration in the formation of lipofuscin-laden AP in skeletal muscles. Interestingly, the IL-10tm/tm mice show evidence of enhanced accumulation of damaged mitochondria and AP compared to B6 controls. A possible explanation of this IL-10 genotype effect is that chronic inflammation (i.e. elevated IL-1β, TNF-α) inherent in IL-10tm/tm mice may further impair skeletal muscle’s capacity to dispose of damaged mitochondria (15;16;31). Additionally, because IL-10 could inhibit autophagy in murine macrophages, the absence of IL-10 in IL-10tm/tm mice may be associated with a disinhibition of normal mitophagy (32). Thus, the associated increase in damaged mitochondria and lipofuscin-laden AP in skeletal muscles may underscore a failure of mitochondria and AP clearance or a compensatory response to maintain homeostasis in the setting of sarcopenia-inducing processes such oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction known to be present in IL-10tm/tm mice. (17;27)

Although the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and increase in AP are present in both old IL-10tm/tm and B6 mice, expressions of markers of mitochondrial degradation biology (i.e. NIX, LC3) are different. In old B6, age-associated elevated NIX and LC3 suggest mitophagy induction in skeletal muscles. This observation, while consistent with studies that show an increase in autophagy markers in aged muscles (33;34), contrasts with many studies that show aging-associated decline in mitophagy (24–30). A possible explanation for this discrepancy may be the extreme ages (3–5 months-old vs. 22–24 months-old) of mice used in this study. Similar increase in LC3 protein expression has been observed in the biceps femoris muscle of 22 months-old B6 compared to 3 months-old controls (33). [In contrast to B6, age-associated changes in NIX and LC3 expression are absent in skeletal muscles of old IL-10tm/tm mice. These differences suggest that in IL-10tm/tm mice a chronic inflammatory state may influence age-associated changes in the molecular regulation of mitochondrial degradation and turnover. While the mechanisms underlying these differences are unknown and beyond the scope of this brief report, future mechanistic experiments focused on the dynamic process of mitophagy flux are needed to help address this knowledge gap.

These findings, while certainly not conclusive, support the hypothesis that altered mitophagy may be operant in the accelerated decline in age-associated muscle weakness, abnormalities in energy generation, and frailty previously reported in the IL-10tm/tm mice (15–17). While many previous studies have shown that a combination of mitochondrial and autophagy dysfunction could contribute to age-associated degenerative and neuromuscular diseases (24–26;35–38), others have shown that reduced NIX signaling many be protective (39). In the skeletal muscles of old IL-10tm/tm mouse, the reduction in NIX is accompanied by TEM evidence of mitochondrial damage and altered mitophagy, and inhibition of apoptosis and mitochondria-dependent death pathway (increased anti-NIX cytokine MIF). These concurrent changes may suggest a protective role of NIX-MIF in the context of altered mitochondrial degradation and clearance in the skeletal muscles of chronically inflamed mice. In view of the mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging, whereby abnormal lipofuscin-laden autophagosomes fail to clear abnormal mitochondria, which in turn further increase oxidative stress damage and perhaps trigger apoptosis, these observations may underscore a compensatory response of skeletal muscles to maintain cellular homeostasis in the setting of chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. (27).

Aging, chronic inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction are closely linked. Given that the IL-10tm/tm mouse demonstrates key features of frailty including early onset muscle weakness (15), chronic inflammation (15;16), and ATP kinetics impairment, future studies utilizing this mouse as an in vivo model to explore molecular mechanisms connecting the dynamic process of mitophagy flux, mitochondrial energy production, chronic inflammation, loss of muscle mass, and frailty are merited.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (P30-AG021334, R21-AG025143); the American Federation for Aging Research; T-32 (AG000120); National Institute on Aging Grant K23 (AG035005–01) and Nathan Shock in Aging Scholarship Award (to P.M.A.); and the Mount Sinai Clinical and Translational Science Award (5KL2RR029885) and National Institute on Aging K08 (AG050808) (to F.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J.Gerontol.A Biol.Sci.Med.Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, Tracy RP, Kop WJ, Hirsch CH, Gottdiener J, Fried LP. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch.Intern.Med. 2002;162:2333–2341. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J.Gerontol.A Biol.Sci.Med.Sci. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen HJ, Harris T, Pieper CF. Coagulation and activation of inflammatory pathways in the development of functional decline and mortality in the elderly. Am.J.Med. 2003;114:180–187. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Topinkova E, Michel JP. Understanding sarcopenia as a geriatric syndrome. Curr.Opin.Clin.Nutr.Metab Care. 2010;13:1–7. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333c1c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue Q, Ferrucci L, Walston J, Guralnik JM, Chaves P, Zeger S, Fried LP. Phenotype of Frailty: Characterization in the Women's Health and Aging Studies. Journal of Gerontology. 2006;61:260–261. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson CM, Johannsen DL, Ravussin E. Skeletal muscle mitochondria and aging: a review. J.Aging Res. 2012;2012:194821. doi: 10.1155/2012/194821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Burgh R, Nijhuis L, Pervolaraki K, Compeer EB, Jongeneel LH, van GM, Coffer PJ, Murphy MP, Mastroberardino PG, Frenkel J, Boes M. Defects in mitochondrial clearance predispose human monocytes to interleukin-1beta hypersecretion. J.Biol.Chem. 2014;289:5000–5012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.536920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Mitochondrial homeostasis: the interplay between mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis. Exp.Gerontol. 2014;56:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reimann J, Schnell S, Schwartz S, Kappes-Horn K, Dodel R, Bacher M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in normal human skeletal muscle and inflammatory myopathies. J.Neuropathol.Exp.Neurol. 2010;69:654–662. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181e10925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumann R, Casaulta C, Simon D, Conus S, Yousefi S, Simon HU. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor delays apoptosis in neutrophils by inhibiting the mitochondria-dependent death pathway. FASEB J. 2003;17:2221–2230. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0110com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Ney PA. NIX induces mitochondrial autophagy in reticulocytes. Autophagy. 2008;4:354–356. doi: 10.4161/auto.5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yussman MG, Toyokawa T, Odley A, Lynch RA, Wu G, Colbert MC, Aronow BJ, Lorenz JN, Dorn GW. Mitochondrial death protein Nix is induced in cardiac hypertrophy and triggers apoptotic cardiomyopathy. Nat.Med. 2002;8:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nm719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damico RL, Chesley A, Johnston L, Bind EP, Amaro E, Nijmeh J, Karakas B, Welsh L, Pearse DB, Garcia JG, Crow MT. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor governs endothelial cell sensitivity to LPS-induced apoptosis. Am.J.Respir.Cell Mol.Biol. 2008;39:77–85. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0248OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walston J, Fedarko N, Yang H, Leng S, Beamer B, Espinoza S, Lipton A, Zheng H, Becker K. The Physical and Biological Characterization of a Frail Mouse Model. Journal of Gerontology. 2008;63:391–398. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko F, Yu Q, Xue QL, Yao W, Brayton C, Yang H, Fedarko N, Walston J. Inflammation and mortality in a frail mouse model. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:705–715. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9269-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akki A, Yang H, Gupta A, Chacko VP, Yano T, Leppo MK, Steenbergen C, Walston J, Weiss RG. Skeletal muscle ATP kinetics are impaired in frail mice. Age (Dordr) 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9540-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding WX, Ni HM, Li M, Liao Y, Chen X, Stolz DB, Dorn GW, Yin XM. Nix is critical to two distinct phases of mitophagy, reactive oxygen species-mediated autophagy induction and Parkin-ubiquitin-p62-mediated mitochondrial priming. J.Biol.Chem. 2010;285:27879–27890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang YC, Su WH, Lei HY, Lin YS, Liu HS, Chang CP, Yeh TM. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces autophagy via reactive oxygen species generation. PLoS.One. 2012;7:e37613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frazier EP, Isenberg JS, Shiva S, Zhao L, Schlesinger P, Dimitry J, Abu-Asab MS, Tsokos M, Roberts DD, Frazier WA. Age-dependent regulation of skeletal muscle mitochondria by the thrombospondin-1 receptor CD47. Matrix Biol. 2011;30:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arismendi-Morillo G. Electron microscopy morphology of the mitochondrial network in human cancer. Int.J.Biochem.Cell Biol. 2009;41:2062–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Divi RL, Haverkos KJ, Humsi JA, Shockley ME, Thamire C, Nagashima K, Olivero OA, Poirier MC. Morphological and molecular course of mitochondrial pathology in cultured human cells exposed long-term to Zidovudine. Environ.Mol.Mutagen. 2007;48:179–189. doi: 10.1002/em.20245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marzetti E, Calvani R, Cesari M, Buford TW, Lorenzi M, Behnke BJ, Leeuwenburgh C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: from signaling pathways to clinical trials. Int.J.Biochem.Cell Biol. 2013;45:2288–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajawat YS, Bossis I. Autophagy in aging and in neurodegenerative disorders. Hormones.(Athens) 2008;7:46–61. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1111037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandri M. Autophagy in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1411–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masiero E, Sandri M. Autophagy inhibition induces atrophy and myopathy in adult skeletal muscles. Autophagy. 2010;6:307–309. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terman A, Kurz T, Navratil M, Arriaga EA, Brunk UT. Mitochondrial turnover and aging of long-lived postmitotic cells: the mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging. Antioxid.Redox.Signal. 2010;12:503–535. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutta D, Xu J, Dirain ML, Leeuwenburgh C. Calorie restriction combined with resveratrol induces autophagy and protects 26-month-old rat hearts from doxorubicin-induced toxicity. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2014;74:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph AM, Adhihetty PJ, Wawrzyniak NR, Wohlgemuth SE, Picca A, Kujoth GC, Prolla TA, Leeuwenburgh C. Dysregulation of mitochondrial quality control processes contribute to sarcopenia in a mouse model of premature aging. PLoS.One. 2013;8:e69327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marzetti E, Csiszar A, Dutta D, Balagopal G, Calvani R, Leeuwenburgh C. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and altered autophagy in cardiovascular aging and disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am.J.Physiol Heart Circ.Physiol. 2013;305:H459–H476. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00936.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Inflammaging: disturbed interplay between autophagy and inflammasomes. Aging (Albany.NY) 2012;4:166–175. doi: 10.18632/aging.100444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park HJ, Lee SJ, Kim SH, Han J, Bae J, Kim SJ, Park CG, Chun T. IL-10 inhibits the starvation induced autophagy in macrophages via class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. Mol.Immunol. 2011;48:720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenz T, Rossi SG, Rotundo RL, Spiegelman BM, Moraes CT. Increased muscle PGC-1alpha expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2009;106:20405–20410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911570106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.O'Leary MF, Vainshtein A, Iqbal S, Ostojic O, Hood DA. Adaptive plasticity of autophagic proteins to denervation in aging skeletal muscle. Am.J.Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C422–C430. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00240.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Debnath J, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Does autophagy contribute to cell death? Autophagy. 2005;1:66–74. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim I, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Lemasters JJ. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 2007;462:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinet W, De Meyer GR. Autophagy in atherosclerosis: a cell survival and death phenomenon with therapeutic potential. Circ.Res. 2009;104:304–317. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green DR, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Mitochondria and the autophagy-inflammation-cell death axis in organismal aging. Science. 2011;333:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1201940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimoto K, Ford EL, Tran H, Wice BM, Crosby SD, Dorn GW, II, Polonsky KS. Loss of Nix in Pdx1-deficient mice prevents apoptotic and necrotic β cell death and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4031–4039. doi: 10.1172/JCI44011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]