Abstract

Context/objective

To examine the effects of repetitive QuadroPulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMSQP) on hand/leg function after spinal cord injury (SCI).

Design

Interventional proof-of-concept study.

Setting

University laboratory.

Participants

Three adult subjects with cervical SCI.

Interventions

Repeated trains of magnetic stimuli were applied to the motor cortical hand/leg area. Several exploratory single-day rTMSQP protocols were examined. Ultimately we settled on a protocol using three 5-day trials of (1) rTMSQP only; (2) exercise only (targeting hand or leg function); and (3) rTMSQP combined with exercise.

Outcome measures

Hand motor function was assessed by Purdue Pegboard and Complete Minnesota Dexterity tests. Walking function was based on treadmill walking and the Timed Up and Go test. Electromyographic recordings were used for neurophysiological testing of cortical (by single- and double-pulse TMS) and spinal (via tendon taps and electrical nerve stimulation) excitability.

Results

Single-day rTMSQP application had no clear effect in the 2 subjects whose hand function was targeted, but improved walking speed in the person targeted for walking, accompanied by increased cortical excitability and reduced spinal excitability. All 3 subjects showed functional improvement following the 5-day rTMSQP intervention, an effect being even more pronounced after the five-day combined rTMSQP + exercise sessions. There were no rTMSQP-associated adverse effects.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a functional benefit of motor cortical rTMSQP after SCI. The effect of rTMSQP appears to be augmented when stimulation is accompanied by targeted exercises, warranting expansion of this pilot study to a larger subject population.

Keywords: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, Motor function, Rehabilitation, Spinal cord injury

In human beings, recovery of voluntary motor function in segments caudal to a spinal cord injury (SCI) is highly unlikely without contribution from at least some corticospinal tract (CST) fibers.1,2 Even with sparing of fibers, spontaneous reorganization within the injured CST may give rise to only modest functional recovery.3 Moreover, structural changes in the cortex and pathways both rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter may provide additional barriers for restoring motor function following SCI.4–7

Non-invasive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the motor cortex, a powerful tool for modulating excitability of the motor cortex, has been used to treat a variety of neurological disorders, including stroke, Parkinson's disease, and multiple sclerosis.8 Several groups have used rTMS for supraspinal targeting of motor function in persons with SCI. Improved hand dexterity accompanied by reductions in cortical inhibition has been observed after 5 days of paired-pulse rTMS in 4 subjects with motor-incomplete cervical SCI.9 Improvements in walking ability coincident with lowered spasticity were seen following 15 sessions of high-frequency (20-Hz) rTMS.10 Finally, 5-Hz rTMS applied over the hand motor area on 5 successive days modulated corticospinal excitability and improved hand gross motor skills in persons with injury to the cervical spinal cord.11

A novel form of rTMS—known as QuadroPulse stimulation—combines features of low- and high-frequency rTMS. This device produces 4-pulse trains of ultra high frequency (e.g. 2 ms interpulse interval), with no fewer than 5 seconds between trains (i.e. 0.2 Hz). A single-session application of QuadroPulse rTMS (rTMSQP) in able-bodied subjects was recently shown to safely increase cortical excitability more effectively than paired-pulse stimulation.12,13 We wanted to see if a comparable effect of rTMSQP on motor cortex excitability in persons with SCI might lead to improvement in motor function. We report herein our findings of a wide-ranging exploration of different regimens of rTMSQP delivery—both alone and in combination with targeted exercise—in a small population of persons with SCI. Given the differences in subject characteristics, regions of motor cortex being targeted, and ‘dose’ of rTMSQP delivered, we present our findings in the form of 3 different case studies.

Methods

Experiments were conducted on three adult subjects (Table 1). The inclusion criteria were: (1) injury at or rostral to T10 vertebrae (i.e. excluding persons with conus or cauda equina lesion); (2) post-injury time of at least 6 months; (3) some hand dexterity or walking ability; and (4) no contraindication to TMS (e.g. seizure history; implanted electronic device).

Table 1 .

Subject demographic and clinical characteristics

| Subject #1 | Subject #2 | Subject #3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26 | 31 | 52 |

| Sex | M | F | F |

| Level of SCI (bone) | C6 | C7 | C5 |

| Time post-injury (m) | 28 | 9 | 33 |

| AIS | D | B | C |

| FIM | 89 | 32 | 61 |

| WISCI II | 19 | 0 | 17 |

SCI, Spinal Cord Injury; m, months; AIS, American Spinal Association Impairment Scale; FIM, Functional Independence Measure, Motor Subtotal Score is only given (maximal score=91); WISCI II, Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury (maximal score=20).14

Subjects gave their informed consent to participate in this study approved by Upstate Medical University's IRB. Because it is considered an experimental device, an Investigational Device Exemption (G020083) was granted by the US Food and Drug Administration to B. Calancie (Sponsor/Investigator) for use of the QuadroPulse stimulator (Magstim Company Ltd, Whitland, United Kingdom).

QuadroPulse TMS was comprised of four-pulse trains with an intertrain interval of 5–6 seconds (i.e. ∼0.2–0.15 Hz train delivery rate). Individual stimulus pulses were identical in magnitude, corresponding to 0.8–0.9 times the single-pulse motor threshold measured when the subject was at rest. The within-train instantaneous stimulus rate ranged between 250 and 500 Hz (i.e. 4–2 ms interpulse interval). The number of trains delivered within a single daily session was either 250 or 360 (i.e. approximately 23 or 33 minutes of train delivery). When targeting hand function, either a round or flat figure-8 coil was used for stimulation over the hand area of the contralateral motor cortex, whereas a large double-cone coil over the vertex was used for bilateral and simultaneous targeting of the leg areas.

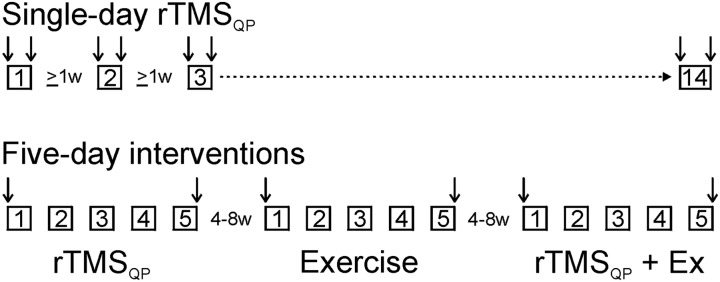

As this was our first experience using rTMSQP in persons with SCI, we did not settle upon a final protocol immediately, but instead tried both single-day and five-day exposures, as summarized in Fig. 1. Single-session rTMSQP was examined extensively in subjects number 1 and 3, in which we varied interstimulus intervals and numbers of applied trains; subject number 2, due to family matters, received only one single-day rTMSQP session. In all cases at least 1 week elapsed between one single-day rTMSQP session and the next (Fig. 1—top). Mixed results from these sessions led us to examine in all 3 subjects the effect of 5 successive daily sessions of rTMSQP and/or targeted exercises, in which case at least 4 weeks elapsed between one 5-day session and the next (Fig. 1—bottom). These 5-day sessions took one of 3 forms, and were delivered in the same order across subjects: (1) rTMSQP alone; (2) targeted exercise alone (hand dexterity or treadmill walking); and (3) rTMSQP followed immediately by either hand dexterity exercises or treadmill walking. For all 5-day sessions, testing—indicated by vertical arrows in Fig. 1—was done immediately before the start of session number 1 (i.e. on Day 1), and immediately after the conclusion of session number 5 (i.e. on Day 5).

Figure 1 .

Study flow diagram; each box represents delivery of an rTMSQP session. Two series of experiments–single-day rTMSQP and five-day interventions–were conducted in each subject. Subjects number 1 and 3 participated in 14 single-day rTMSQP sessions each; subject number 2 participated in only one single-day session. Vertical arrows indicate when testing was done (e.g. immediately before and after each single-day session; immediately before day-1 and after day-5 sessions). Single-day sessions were separated by at least one week. All subjects underwent three different five-day interventions: rTMSQP alone; exercises alone; and rTMSQP + exercises. All 5-day sessions were separated from the next by 4–8 weeks.

Hand motor training (subjects number 1 and 2) consisted of 10 standardized exercises performed 10 times each training day and restricted to the subject's weaker hand. Tasks included grasp and release, isometric and concentric contractions of wrist, thumb, and interphalangeal joints in flexion, extension, abduction and abduction, and hand pronation/supination. For ambulation training (subject number 3), the subject walked on a custom treadmill (minimum belt speed = 0.05 m/s) at a self-selected pace for 30 minutes. This subject was encouraged to choose a walking pace that she felt was at the high end of her capacity to maintain throughout the training session.

Hand dexterity was assessed by a subset of the Purdue Pegboard test (Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN) using pin-placement for one hand only (30-second trials; number of pins averaged for 3 trials) and excluding the “assembly” component. We also used the ‘Turning and Displacement’ portion (the total time (in seconds) to complete 2 trials) of the Complete Minnesota test (Lafayette Instrument Company, Lafayette, IN, USA), modified in that subjects were tested seated, and only a single board with 40 “wells” was included—instead of the standard 2 boards with 60 wells each—due to difficulty with balance/reach. Walking ability was assessed by the maximal walking speed (m/s) our subject could attain during a 2-minute period of treadmill walking, with the stipulation that at least 2 complete step cycles had to be performed at that speed. We also had our subject perform the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test (total time in seconds) before and after multiple individual sessions of rTMSQP delivery.

During electrophysiological procedures, subjects were tested in a sitting position. EMG activity was recorded bilaterally using pairs of self-adhesive surface electrodes placed over the extensor carpi radialis (ECR), flexor carpi radialis (FCR), abductor pollicis brevis, and adductor digiti minimi muscles in the upper limbs (subjects number 1 and 2). In the lower limbs, EMG was recorded bilaterally from quadriceps, tibialis anterior, soleus, and abductor hallucis (AbH) muscles bilaterally (subject number 3). Single-pulse TMS was used to measure motor evoked potential (MEP) resting threshold (RT) of the FCR (or ECR, if no response in FCR) muscle in the upper limbs, and the AbH in the lower limbs, in each case targeting the subject's weaker side. The peak-to-peak MEP amplitude and cortical silent period duration were tested at a stimulus intensity 1.2 times RT. Intracortical facilitation (ICF) and short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) were tested with double-pulse TMS,15 using conditioning and testing stimulus intensities of 0.8 and 1.2 times RT, respectively. Spinal monosynaptic reflexes (i.e. the T-response) were evoked from wrist flexors and quadriceps using mechanical taps to the FCR and patellar tendons, respectively. Constant-current stimulus pulses (0.2 ms pulse duration) were delivered to the tibial nerve at the popliteal fossa in subject number 3 to elicit the H-reflex from the soleus muscle to quantify Hmax:Mmax (0.2 Hz stimulus rate), and to examine low-frequency depression. For this latter test, we delivered 3 stimuli to the tibial nerve at constant intensity (sufficient to elicit both M-and H-waves, on the rising edge of the H recruitment curve) and varying stimulus rates, measuring the peak-to-peak amplitudes of H3/H1 for each rate delivered, as described previously.16 The MEP, T-response, M-response, and H-reflex amplitudes were measured in mV; the latency of responses and the silent period duration were measured in ms.

Results from the multiple single-session rTMSQP trials conducted in subjects number 1 and 3 were calculated, normalized, and averaged (mean ± SD). Because this proof-of-concept study involved multiple evaluations on a small number of subjects, statistical comparisons between pre- vs post-intervention differences within or between subjects were not calculated due to the expectation that the study would be underpowered.

Results

Single-day rTMSQP

Subject number 1 received 14 single-day applications of rTMSQP over the motor area innervating his targeted (i.e. weaker) hand, with at least one week separating each of these sessions. There was little difference in Purdue Pegboard (PPT) or Minnesota Dexterity (CPM) test scores after a single rTMSQP session compared to pre-testing scores, as summarized in Table 2. Although there was no obvious benefit to hand function of single-day rTMSQP, there was a large increase in the mean amplitude of the test MEP after this stimulation. Conversely, spinal excitability as judged by the T-response to taps of wrist flexor tendons was attenuated, suggesting the larger MEP was due to increased cortical outflow, rather than to higher spinal excitability. None of the RT, MEP latency, SICI, ICF, or silent period measures were affected by a single session of rTMSQP (data not shown).

Table 2 .

Functional and neurophysiologic test results of single-session rTMSQP delivery. Data (mean ± SD) are normalized to pre-rTMSQP measures

| Subject #1 | Subject #2 | Subject #3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexterity | |||

| PPT | 101.5 ± 12.7 | 122.3* | – |

| CMT | 101.3 ± 5.0 | 96.5* | – |

| Walking | |||

| TM | – | – | 173.7 ± 19.3 |

| TUG | – | – | 102.7 ± 5.2 |

| MEP size | 146.5 ± 32.0 | 118.5* | 125.2 ± 40.3 |

| T-response size | 65.1 ± 16.7 | 96.0* | 91.1 ± 19.7 |

PPT, Purdue Pegboard Test; CMT, Complete Minnesota Test; TM, Treadmill walking speed; TUG, Timed Up and Go Test; MEP size, motor evoked potential amplitude; T-response size, wrist-flexor (Hand) or patellar (Leg) Tendon tap response.

*Single trial measures are presented.

Subject number 2 received only one single-day session of rTMSQP. Post-testing showed a moderate improvement in pin placement but little difference in her “Turning and Displacement” test scores (Table 2; asterisk denotes a single measurement). Cortical excitability as judged by MEP amplitude was increased, and spinal excitability was slightly lower, but in all cases these findings must be tempered by the fact they reflect results from only a single rTMSQP session.

Whereas single sessions of rTMSQP had limited impact on hand function in the two subjects tested, the one subject (number 3) tested with rTMSQP targeting her motor cortex leg area (n = 14 sessions) showed a marked (∼75%) increase in treadmill-based maximal walking speed, and modest increases in MEP amplitude in AbH muscles after stimulation (Table 2). Other measures of TMS-evoked responses (RT, MEP latency, SICI, ICF, silent period) in subject number 3 were unchanged (not shown). Average times to complete the TUG test showed no consistent difference after a single session of rTMSQP. Finally, there was a moderate drop in patellar tendon response amplitudes for subject number 3 (Table 2), but no obvious change in Hmax:Mmax (not shown).

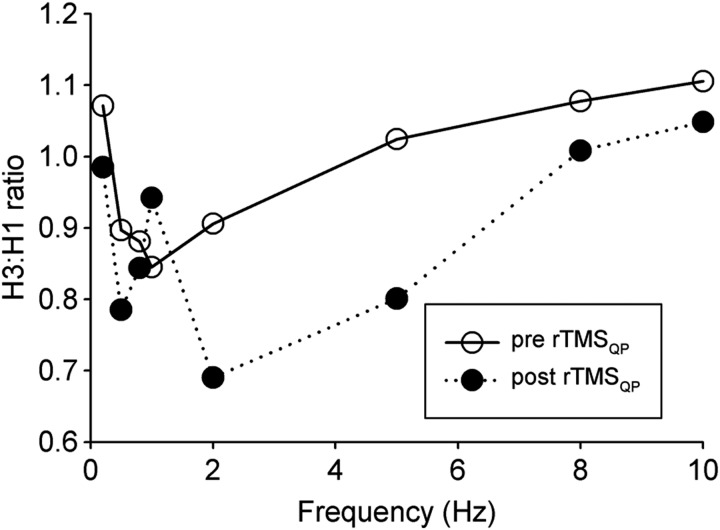

One spinal-based parameter that did change after a single rTMSQP session targeting the lower limbs was low-frequency depression of the H-reflex. Based on findings from a single session of rTMSQP, Fig. 2 shows that across almost all test frequencies the post-rTMSQP ratio of H3:H1 was lower, particularly at 2- and 5-Hz, compared to values immediately before delivery of rTMSQP stimulus trains. In this case, measurements were made on the subject's left leg, which was her weaker side.

Figure 2 .

The effect of single-day rTMSQP of the leg motor area on soleus H-reflex low-frequency depression. The tibial nerve was stimulated at the popliteal fossa using square-wave, constant-current pulses (0.2 ms pulse duration). Stimulus intensity was adjusted to cause a constant M-wave, and an H-reflex of the same or slightly larger amplitude, on the rising edge of the stimulus-response curve. Using identical stimulus intensities, three pulses were delivered at each of 7 different rates (0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 8, and 10 Hz). At least 10 seconds separated each 3-pulse delivery from the next. For each tested frequency of stimulation, the amplitudes (peak-to-peak) of the last (H3) and the first (H1) responses are expressed as H3:H1 ratio. Note that post-rTMSQP H3:H1 values (filled symbols) at 2–10 Hz are lower than pre rTMSQP (open symbols) data, indicative of greater H-reflex depression.

Five-day interventions

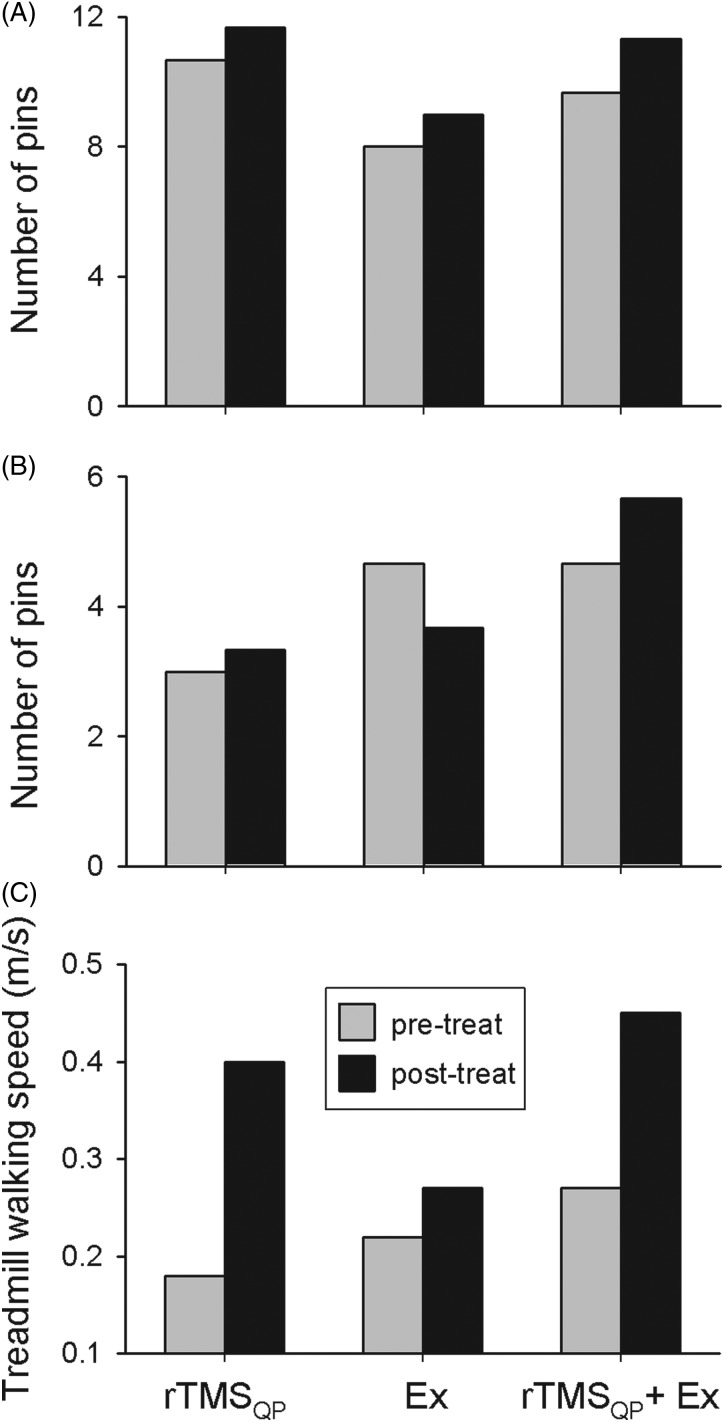

The effect of different 5-day trials utilizing exercise and rTMSQP–alone and in combination–on either hand dexterity or walking were examined in each of our 3 subjects, the results of which are presented individually in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 .

The effects of three different 5-day trials utilizing rTMSQP alone, exercise alone (‘Ex’), and rTMSQP in combination with exercise on hand dexterity in subject number 1 (A) and subject number 2 (B) and walking in subject number 3 (C). In (A) and (B), the absolute number of pins placed during the Purdue Pegboard dexterity test by the subject immediately after the day-5 rTMSQP session (black columns) is compared to the value immediately before the day-1 session's score (grey columns). (C) illustrates the absolute maximal treadmill walking speed measured in subject number 3 before (grey columns) and after (black columns) each of the 3 interventions.

In subject number 1, rTMSQP was delivered to the hand area of his right motor cortex, targeting left hand function. The left-most bars of Fig. 3A show that following 5 days of rTMSQP only (‘rTMSQP’), his pin-placement performance showed ∼10% improvement over that seen immediately before the Day 1 rTMSQP session. After a one-month washout period, five successive days of hand exercise (only) resulted in comparable improvement in pin-placement relative to the effect of rTMSQP alone in this subject (Fig. 3A—middle bars—‘Ex’). The combination of rTMSQP + exercise led to the largest improvement in pin-placement performance in this subject (Fig. 3A—right-most bars—“rTMSQP + Ex”), again following a one-month washout period from the prior 5-day series of hand exercises. Findings for the “Turning and Displacement” test led to modest (5–10%) improvements for all 3 interventions on subject number 1's treated hand (data not shown), without obvious differences between the 3 interventions.

Hand function was targeted in subject number 2, who showed a modest improvement in pin placement after rTMSQP alone (Fig. 3B—left-most bars). Pin placement performance was worse in this subject's weaker hand after the exercise-only intervention (Fig. 3B—middle bars), but she had developed a significant urinary tract infection (UTI) and was experiencing a pronounced increase in spasticity during this period of intervention. Six weeks later, and when her UTI had resolved, this subject's pin placement after the combination of rTMSQP + exercise showed a 20% improvement over her pre-intervention performance. As for subject number 1, scores of the ‘Turning and Displacement’ test in subject number 2 were all modestly better after the 5-day intervention (not shown), but there were no obvious differences in improvements between interventions.

In subject number 3, rTMSQP was delivered to the leg area of the motor cortex to target walking function. As shown in Fig. 3C, large improvements in maximum walking speed occurred after both rTMSQP alone, and after the rTMSQP + exercise intervention. In fact this combined approach led to the fastest walking speeds the subject had yet achieved post-injury. In contrast, treadmill training alone had little effect on walking speed (Fig. 3C—middle bars). Note also that the “pre-treatment” walking speeds were progressively higher across the 3 intervention periods, suggesting a carryover from one training session to the next, even though sessions were separated from one another by at least one month. Finally, and as we saw for one-day interventions summarized above, this subject did not show any consistent improvement in TUG measures upon completion of any of the interventions examined, as her ability to go from sit-to-stand, and to turn once standing, appeared to be the same before and after both single-day and five-day rTMSQP sessions, negating any improvements in walking speed that might have occurred during this test (data not shown).

There were no adverse events associated with rTMSQP delivery. One side effect that was reported by 2 of our 3 subjects and described as being quite pleasant was a feeling of drowsiness brought on within a minute or two of beginning rTMSQP delivery. In both subjects, this sensation persisted for the duration of stimulation and for about 5 minutes after its discontinuation. Finally, all 3 subjects said that they felt “less rigid” and ‘more loose’ after completing any single session that included rTMSQP.

Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study we examined the effect that QuadroPulse rTMS stimulation has on hand and leg motor function diminished by spinal cord injury. The QuadroPulse stimulator delivers patterned rTMS shown to induce a broad range of cortical plasticity, varying from MEP facilitation to suppression depending on the parameters of stimulation.12,13 In contrast to other rTMS techniques, the modulating effect of rTMSQP on motor cortex does not depend on polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene, thus minimizing inter-individual variability, a critical aspect in any clinical study.17 Although as many as 4 closely-spaced pulses can be delivered within each train, the QuadroPulse stimulator restricts the delivery of successive stimulus trains to rates not higher than 0.2 Hz (i.e. one train every 5 seconds). Our study included only 3 subjects, but collectively they received well over 12 000 individual 4-pulse rTMS trains of an intensity that—while sub-threshold for their impaired central motor systems—would have far exceeded threshold intensities for virtually all able-bodied subjects,18 yet they were seizure-free. Our findings in this small sample that the QuadroPulse rTMS pattern presents no more of a seizure risk to subjects than does low-frequency rTMS are consistent with one other report.19

In the present case study on 3 subjects with a history of spinal cord injury, we combined low-frequency trains (0.2 Hz), short interpulse intervals (2–4 ms) and subthreshold stimulus intensities in an attempt to increase motor cortical excitability, as has been shown in able-bodied subjects.12 Stimulation to leg area motor cortices was bilateral for subject number 3, yet the protocol we used when unilaterally stimulating the hand area has been shown to affect motor cortex excitability bilaterally by increasing inter-hemispheric interactions via the corpus callosum.20

In the absence of any other intervention, even a single session of rTMSQP over the hand/forearm cortical motor area in our 2 subjects (numbers 1 and 2) targeted for hand function sometimes caused a modest improvement in dexterity of the treated hand, and was accompanied by modest increases in cortical and decreases in spinal excitability as assessed by MEP facilitation and T-response reduction, respectively. However, these effects were inconsistent within and between the 2 subjects, as evidenced by the large variance across trials.

A better-defined trend towards functional improvement, including an increase in walking speed accompanied by increased corticospinal output and an increase in low-frequency depression of the H-reflex, was seen following rTMSQP applied over the leg motor area in the one subject (number 3) whose leg function was targeted. Although in this subject the overall size of monosynaptic spinal reflexes did not change after rTMSQP, the downward shift in the H-reflex low-frequency depression curve in this subject approached values previously described for able-bodied subjects, indicating an increase in presynaptic inhibition of Ia-afferent input16 following rTMSQP to the leg area of this subject's motor cortex. Moreover, this normalization of spinal presynaptic inhibition has been associated with improved motor control in both animal models21–23 and human studies24–27 of SCI.

Our 2 hand-function subjects completed only one series of 3 different 5-day interventions, hence we cannot address variance within subjects. However, in both subjects their best improvement in performance of all different times being tested was immediately after completing the 5-day rTMSQP + exercise study combination. The modest functional improvements seen suggest slightly greater cortical outflow coupled with a diminution of excess spinal excitability that might otherwise interfere with these descending motor commands.

Improvements in walking speed after the five-day combined rTMSQP + exercise regimen in our one subject whose leg function was targeted by rTMS were even more pronounced than the improvements described above for hand function. Should this effect be carried over to a larger sample size, it would suggest that walking, with its strong spinal component through existence of a central pattern generator,28 is readily-impacted by the relatively crude inputs we delivered to motor cortex. Conversely, the limited gains we noted in hand function following rTMSQP may reflect the need for more moment-by-moment modulation of descending inputs to optimize hand function; a similar argument may explain the absence of significant improvement in TUG scores in the one subject so tested, since standing and turning are more complex movements than treadmill walking at a fixed speed.

All three of our subjects reported feeling less spastic after receiving ∼30 minutes of rTMSQP, supporting the hypothesis that segmental stretch reflexes are modulated via corticospinal-mediated rTMS effects.10,29 The finding of an opposing effect of rTMS on motor cortex (i.e. increased excitability) and spinal cord circuitry (i.e. reduced excitability) has been previously described in healthy subjects,30 and may be especially beneficial for neurological patients presenting with cortical hypo- and spinal hyperexcitability. Consistent with the study by Perez and colleagues,30 our preliminary observations suggest that post-rTMSQP functional improvements in SCI subjects may be attributed, at least in part, to rTMSQP-mediated facilitation of motor cortical activity and the resultant optimization of corticospinal drive to the spinal reflex network, perhaps acting via enhanced presynaptic inhibition, leading to a decrease in reflex hyperexcitability.

There are few reports on the potential functional benefits of motor cortical rTMS after SCI.9–11 Multiple rTMS sessions appear to be more effective at eliciting CNS plasticity compared to single, discontinuous sessions.31 Extending this finding, a regimen using 5 daily sessions of rTMS has been adopted in clinically-oriented rTMS studies.32,33 Improved hand dexterity and ASIA motor/sensory scores have been reported in 4 individuals with motor-incomplete cervical SCI following five consecutive days of paired-pulse rTMS (0.1 Hz, 360 doublet stimuli, 90% motor threshold of hand muscles), with sham stimulation producing no effect.9 Likewise, hand and arm gross motor skills were improved by a 5-day high-frequency rTMS regimen (5 Hz, 900 stimuli, subthreshold intensity for upper-limb muscles) in a more recent SCI study conducted in the same institution.11 For repetitive magnetic stimulation of the leg cortical motor area, significant improvement in walking speed and ASIA lower-extremity motor scores was achieved by 15 daily sessions of high-frequency active (20 Hz, 1800 pulses, 90% RMT of upper-limb muscles) but not sham rTMS, both being combined with ambulation training.10

Several studies comparing the effects of different rTMS sessions used washout periods of 2–4 weeks in duration.10,11,34 Our use of a 4-week washout period between different rTMSQP regimens in the present study is therefore not without precedent. Nevertheless, a more rigorous study design would call for either a longer washout period between 5-day sessions of rTMSQP, or randomization of the presentation order of the different regimens used.

We felt it necessary for this pilot study of a novel form of rTMS to include both single-session and five-day regimens of stimulation. Our reasoning included a desire to corroborate earlier studies of the beneficial actions of rTMS on function after CNS trauma, and to simply establish whether subjects were willing to tolerate the discomfort caused by repeated trains of high-intensity TMS pulses delivered by the QuadroPulse stimulator. Note that for our purposes, “Training alone” was chosen as a control intervention due to the fact that our subjects could always discriminate between active and sham forms of stimulation (in this case stimuli of similar intensity but posterior to the motor cortical area). Moreover, sham rTMS has been shown to have the potential for a low but detectable placebo effect.35

Although both rTMSQP (present data) and training36 modalities can facilitate descending corticospinal pathways after neurologically-incomplete SCI, the functional outcome appears to be greater when two modalities (i.e. inputs) are combined, supporting the “more is better” concept.37 In agreement with the above SCI reports, these preliminary data underscore the promise of using repetitive motor cortical stimulation for supraspinal targeting of motor function after SCI, particularly for improving walking ability. Further testing in a larger population of SCI subjects would show whether rTMS, particularly in its low-frequency (and accordingly, low-risk) QuadroPulse mode, could be used as a specific rehabilitative treatment or an add-on modality to more conventional physical therapy. While the latter can be beneficial for improving motor function in persons with chronic, motor-incomplete SCI,38 we propose that rTMSQP may itself prove valuable for restoring function in this SCI subpopulation, particularly in cases when the effect of physical exercise has reached a plateau.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors Natalia Alexeeva was primarily responsible for data acquisition, analysis, and writing the first manuscript draft. The study was conceived of jointly by Drs Alexeeva and Calancie. Dr. Calancie gained regulatory approval for the study, helped with data acquisition and analysis, edited the manuscript, and helped prepare figures.

Funding The study was supported by NIH grant RO1 NS 36542.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the Upstate Medical University's IRB, and all subjects gave their Informed Consent to participate.

References

- 1.Nathan PW. Effects on movement of surgical incisions into the human spinal cord. Brain 1994;117(Pt 2):337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemon RN. Descending pathways in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci 2008;31:195–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oudega M, Perez MA. Corticospinal reorganization after spinal cord injury. J Physiol (Lond) 2012;590(Pt 16):3647–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calancie B, Alexeeva N, Broton JG, Molano MR. Interlimb reflex activity after spinal cord injury in man: strengthening response patterns are consistent with ongoing synaptic plasticity. Clin Neurophysiol 2005;116(1):75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrigley PJ, Gustin SM, Macey PM, Nash PG, Gandevia SC, Macefield VG, et al. Anatomical changes in human motor cortex and motor pathways following complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Cereb Cortex 2009;19(1):224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson LA, Gustin SM, Macey PM, Wrigley PJ, Siddall PJ. Functional reorganization of the brain in humans following spinal cord injury: evidence for underlying changes in cortical anatomy. J Neurosci 2011;31(7):2630–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freund P, Weiskopf N, Ashburner J, Wolf K, Sutter R, Altmann DR, et al. MRI investigation of the sensorimotor cortex and the corticospinal tract after acute spinal cord injury: a prospective longitudinal study. Lancet Neurology 2013;12(9):873–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wassermann EM, Zimmermann T. Transcranial magnetic brain stimulation: therapeutic promises and scientific gaps. Pharmacol Ther 2012;133(1):98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belci M, Catley M, Husain M, Frankel HL, Davey NJ. Magnetic brain stimulation can improve clinical outcome in incomplete spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord 2004;42(7):417–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benito J, Kumru H, Murillo N, Costa U, Medina J, Tormos JM, et al. Motor and gait improvement in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury induced by high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012;18(2):106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuppuswamy A, Balasubramaniam AV, Maksimovic R, Mathias CJ, Gall A, Craggs MD, et al. Action of 5 Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on sensory, motor and autonomic function in human spinal cord injury. Clin Neurophysiol 2011;122(12):2452–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamada M, Hanajima R, Terao Y, Arai N, Furubayashi T, Inomata-Terada S, et al. Quadro-pulse stimulation is more effective than paired-pulse stimulation for plasticity induction of the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol 2007;118(12):2672–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamada M, Ugawa Y. Quadripulse stimulation – a new patterned rTMS. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience 2010;28(4):419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marino RJ, Scivoletto G, Patrick M, Tamburella F, Read MS, Burns AS, et al. Walking index for spinal cord injury version 2 (WISCI-II) with repeatability of the 10-m walk time: inter- and intrarater reliabilities. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2010;89(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Ferbert A, et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;471:501–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calancie B, Broton JG, Klose KJ, Traad M, Difini J, Ayyar DR. Evidence that alterations in presynaptic inhibition contribute to segmental hypo- and hyperexcitability after spinal cord injury in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1993;89:177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura K, Enomoto H, Hanajima R, Hamada M, Shimizu E, Kawamura Y, et al. Quadri-pulse stimulation (QPS) induced LTP/LTD was not affected by Val66Met polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene. Neurosci Lett 2011;487(3):264–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calancie B, Alexeeva N, Broton JG, Suys S, Hall A, Klose KJ. Distribution and latency of muscle responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation of motor cortex after spinal cord injury in humans. J Neurotrauma 1999;16:49–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 2009;120(12):2008–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutsumi R, Hanajima R, Terao Y, Shirota Y, Ohminami S, Shimizu T, et al. Effects of the motor cortical quadripulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (QPS) on the contralateral motor cortex and interhemispheric interactions. J Neurophysiol 2014;111(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson FJ, Parmer R, Reier PJ. Alteration in rate modulation of reflexes to lumbar motoneurons after midthoracic spinal cord injury in the rat. I. Contusion injury. J Neurotrauma 1998;15(7):495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiser TS, Reese NB, Maresh T, Hearn S, Yates C, Skinner RD, et al. Use of a motorized bicycle exercise trainer to normalize frequency-dependent habituation of the H-reflex in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2005;28(3):241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cote MP, Azzam GA, Lemay MA, Zhukareva V, Houle JD. Activity-dependent increase in neurotrophic factors is associated with an enhanced modulation of spinal reflexes after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2011;28(2):299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trimble MH, Kukulka CG, Behrman AL. The effect of treadmill gait training on low-frequency depression of the soleus H-reflex: comparison of a spinal cord injured man to normal subjects. Neurosci Lett 1998;246:186–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz R. Presynaptic inhibition in humans: a comparison between normal and spastic patients. J Physiol Paris 1999;93(4):379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meunier S, Kwon J, Russmann H, Ravindran S, Mazzocchio R, Cohen L. Spinal use-dependent plasticity of synaptic transmission in humans after a single cycling session. J Physiol (Lond) 2007;579(Pt 2):375–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson FJ, Reier PJ, Uthman B, Mott S, Fessler RG, Behrman A, et al. Neurophysiological assessment of the feasibility and safety of neural tissue transplantation in patients with syringomyelia. J Neurotrauma 2001;18(9):931–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calancie B, Needham-Shropshire B, Jacobs P, Willer K, Zych G, Green BA. Involuntary stepping after chronic spinal cord injury: evidence for a central rhythm generator for locomotion in man. Brain 1994;117:1143–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valle AC, Dionisio K, Pitskel NB, Pascual-Leone A, Orsati F, Ferreira MJ, et al. Low and high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of spasticity. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49(7):534–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez MA, Lungholt BK, Nielsen JB. Short-term adaptations in spinal cord circuits evoked by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: possible underlying mechanisms. Exp Brain Res 2005;162(2):202–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumer T, Lange R, Liepert J, Weiller C, Siebner HR, Rothwell JC, et al. Repeated premotor rTMS leads to cumulative plastic changes of motor cortex excitability in humans. Neuroimage 2003;20(1):550–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khedr EM, Kotb H, Kamel NF, Ahmed MA, Sadek R, Rothwell JC. Longlasting antalgic effects of daily sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76(6):833–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Valle AC, Rocha RR, Duarte J, Ferreira MJ, et al. A sham-controlled trial of a 5-day course of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the unaffected hemisphere in stroke patients. Stroke 2006;37(8):2115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chieffo R, De Prezzo S, Houdayer E, Nuara A, Di Maggio G, Coppi E, et al. Deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with H-coil on lower limb motor function in chronic stroke: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95(6):1141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bae EH, Theodore WH, Fregni F, Cantello R, Pascual-Leone A, Rotenberg A. An estimate of placebo effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2011;20(2):355–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas SL, Gorassini MA. Increases in corticospinal tract function by treadmill training after incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 2005;94(4):2844–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein RB, Everaert DG, Roy FD, Chong S, Soleimani M. Facilitation of corticospinal connections in able-bodied people and people with central nervous system disorders using eight interventions. J Clin Neurophysiol 2013;30(1):66–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexeeva N, Sames C, Jacobs PL, Hobday L, Distasio MM, Mitchell SA, et al. Comparison of training methods to improve walking in persons with chronic spinal cord injury: a randomized clinical trial. J Spinal Cord Med 2011;34(4):362–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]