Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with the development of many human diseases, and with poor reproductive performance in laboratory rodents. We currently have no idea how natural selection directly acts on variation in vitamin D metabolism due to a total lack of studies in wild animals. Here, we measured serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentrations in female Soay sheep that were part of a long-term field study on St Kilda. We found that total 25(OH)D was strongly influenced by age, and that light coloured sheep had higher 25(OH)D3 (but not 25(OH)D2) concentrations than dark sheep. The coat colour polymorphism in Soay sheep is controlled by a single locus, suggesting vitamin D status is heritable in this population. We also observed a very strong relationship between total 25(OH)D concentrations in summer and a ewe’s fecundity the following spring. This resulted in a positive association between total 25(OH)D and the number of lambs produced that survived their first year of life, an important component of female reproductive fitness. Our study provides the first insight into naturally-occurring variation in vitamin D metabolites, and offers the first evidence that vitamin D status is both heritable and under natural selection in the wild.

Traditionally, the main physiological role of vitamin D has been considered to be in the development and maintenance of skeletal health. Vitamin D deficiency was demonstrated to be the cause of rickets nearly a century ago but over the past two decades, numerous studies have linked vitamin D deficiency to the development of a wide range of non-skeletal disorders, including the development of numerous inflammatory, neoplastic and autoimmune diseases1,2,3,4. Considerable variation has typically been observed in circulating levels of vitamin D metabolites within healthy human populations5,6,7. This variation has been linked to environmental and phenotypic influences including diet, exposure to sunlight and skin colour, and has a heritable component8,9,10. At least part of the genetic variation observed in vitamin D status is likely to have its origin in our evolutionary past11. However, there remains considerable debate over the importance of potential fitness consequences of vitamin D deficiency in human evolution, in particular with respect to evolution of skin colour11. Epidemiological studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with all-cause mortality in humans12,13,14, while laboratory experiments using rodents have linked deficiency to infertility, reduced pregnancy rates and litter sizes15,16,17,18. This suggests vitamin D metabolism may influence two central components of Darwinian fitness: survival and reproductive success. However, we currently have no idea how natural selection really acts on variation in vitamin D metabolism due to a total lack of studies in the wild. Here, we present the first evidence linking variation in vitamin D metabolites and reproductive fitness from a natural population.

Vitamin D can be obtained from dietary sources or from the endogenous synthesis of vitamin D3 which occurs after photolytic conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol, located in the dermal fibroblasts and epidermal keratinocytes, by the ultraviolet B component of sunlight19. Nutritional forms of vitamin D consist of plant derived vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 which is found in oily fish, eggs and liver. Vitamin D undergoes hydroxylation in the liver to 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and is then converted into the active metabolite, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D, (1,25(OH) 2D) in the kidneys by renal 1-α hydroxylase (CYP27B1)19. Due to the longer half-life and higher serum concentrations of 25(OH)D compared to 1,25(OH)2D, serum concentrations of 25(OH)D are the most widely used assessment of vitamin D status19. In the present study, we measured concentrations of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 in serum collected from a group of female Soay sheep (Ovis aries) which were part of the long-term study in the Village Bay area on the island of Hirta in the St Kilda archipelago. Our aims were: (i) to test whether and how age and other available phenotypic traits, including coat colour, immunological measures, parasite burden and body mass, were associated with 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3; (ii) to determine whether vitamin D concentrations predicted important reproductive fitness traits, including fecundity, offspring birth weight and offspring first year survival.

Soay sheep are descendants of domestic sheep that were present throughout the northwest of Europe during the Bronze age, and probably reached the St Kilda archipelago 3000–4000 years ago20. Previous studies have reported that 25(OH)D concentrations can be influenced by skin pigmentation in humans21,22, and so it is salient that Soay sheep can have either a dark or light coat colour phenotype (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Dark and light coated Soay sheep in the Village Bay area of St Kilda (photo credit Arpat Ozgul).

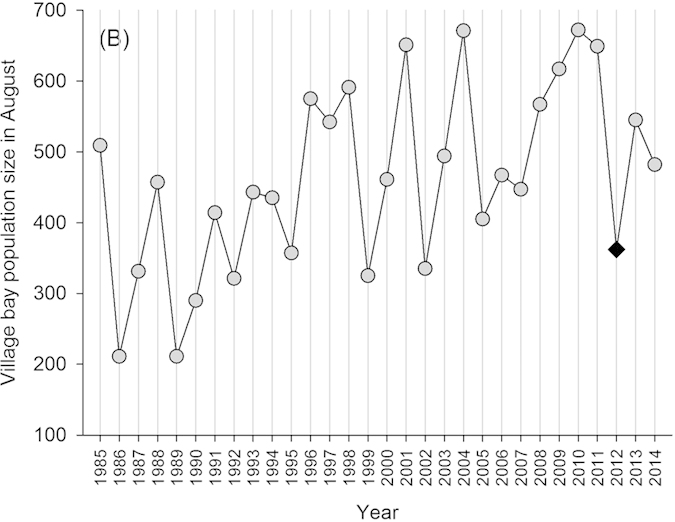

This polymorphism is known to be under the control of a single genetic locus (TYRP1), and occurs on St Kilda at an approximate 3 dark: 1 light ratio23. Soay sheep have been resident to the St Kilda archipelago for thousands of years, but were resident only on the smaller island of Soay until 1930 when around one hundred were moved to the (then uninhabited) larger island of Hirta which is where Village Bay and our study area is located. This population has been the subject of long term individual-based monitoring since 1985, and have been completely unmanaged and unpredated since the 1930s20. Sheep resident to Village Bay are captured and marked at birth and subsequently closely monitored and regularly captured, providing exceptionally detailed reproductive life history and survival data. They are also subject to variable and often very strong natural selection, characterized in particular by irregular ‘crash’ winters when upwards of 60% of the population can perish due to interactions among food limitation, climate conditions and parasite infection (Fig. 2)20. Importantly, the relatively homogeneous (compared to humans) and unsupplemented vegetable diet of the sheep means circulating 25(OH)D3 will be of cutaneous origin, while 25(OH)D2 will be dietary in origin. Here, we test the phenotypic predictors of vitamin D status in wild Soay sheep and, in turn, its ability to predict annual reproductive fitness. We present the first documentation of an association between colouration and serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations from the wild, and the first evidence that higher levels of either 25(OH)D3 or 25(OH)D3 predict improved female fecundity and reproductive fitness under natural conditions.

Figure 2. Annual population size of Soay sheep population in August in Village Bay area on the island of Hirta, with year of sample collection in this study highlighted as a black diamond.

Results

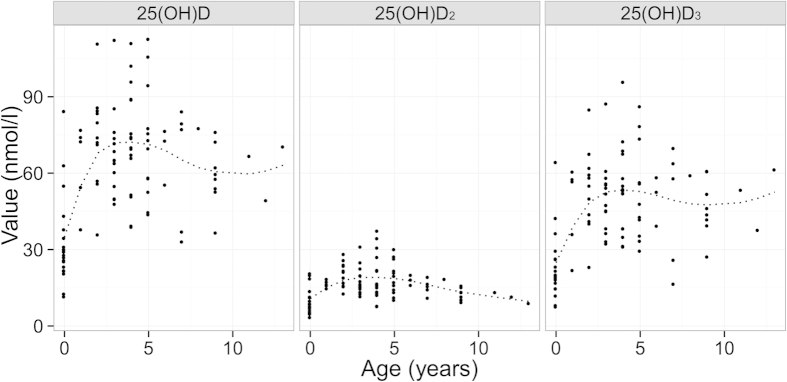

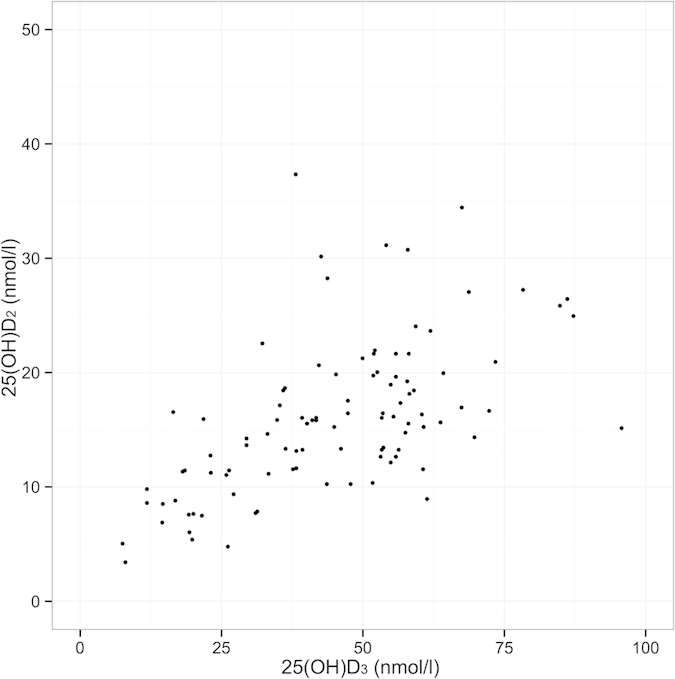

Serum 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 concentrations were positively correlated (r = 0.58, t(99) =7.12, p < 0.001; Fig. 3), although 25(OH)D3 concentration were on average 29.14 ng/ml (95% CI 25.98–32.29 ng/ml) higher and thus contributed considerably more to individual’s total 25(OH)D (Fig. 3). Age explained a considerable amount of variation in 25(OH)D concentrations (Fig. 4). Comparison of models with a smooth function of age (implemented using a generalised additive model) and a three-level categorisation of age (lambs, adults aged 1–6 years, and geriatrics aged 7 years or more) revealed that the latter adequately described variation in all three vitamin D measures (ΔAIC was lower for all categorical models compared to the respective general additive models: 25(OH)D2 =−5.86, 25(OH)D3 = −7.96, total 25(OH)D = −8.31). The three category age function explained a considerable amount of variation in all three measures: r2 = 0.42, 0.31 and 0.39, respectively. For the 3 general additive models r2 was 25(OH)D2 = 0.28, 25(OH)D3 = 0.35, total 25(OH)D = 0.38.

Figure 3. Scatterplot showing relationship between 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3.

Figure 4. Association between age and serum concentrations of total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3.

Individual results are shown as dots. Fitted general additive model shown as dotted line.

Serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations were significantly higher in adults and geriatrics than lambs (p < 0.05 Tukey HSD test) and 25(OH)D2 concentration was significantly higher in adults than geriatrics and lambs (p < 0.05 Tukey HSD test). Serum 25(OH)D showed a decline from adult to geriatric age groups which was only statistically significant for 25(OH)D2 concentrations (mean difference 8.76 ng/ml, 95% CI 3.08–7.43, p < 0.001 unpaired T-Test).

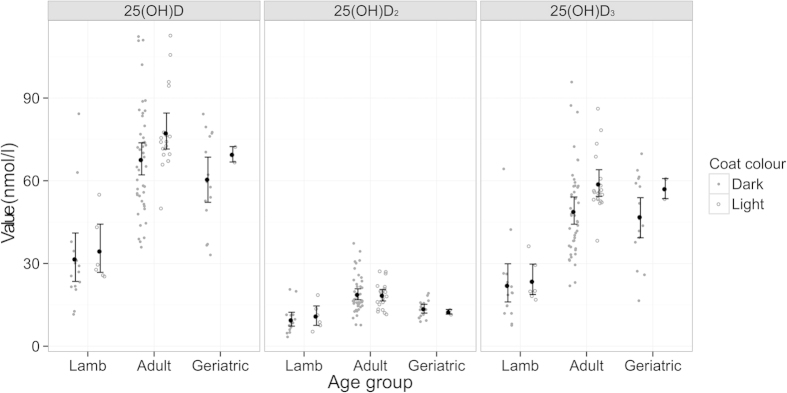

Once age was accounted for, our main findings were that light coated ewes had higher 25(OH)D3 concentrations than dark ones (mean 25(OH)D3 concentration in light sheep was 8.11 ng/ml 95% CI 1.52–14.71 higher than in dark sheep, p = 0.014) (Fig. 5) and that 25(OH)D2 concentrations were positively associated with anti-T. circumcincta IgE levels (p = 0.003) and positively associated with weight (p = 0.046). T. circumcincta is an important gastrointestinal parasite of sheep and there is good evidence that on St Kilda these parasites exert a considerable selective pressure on Soay sheep24.

Figure 5. Association between 25(OH)D concentration, age and coat colour.

Black points show mean with 95% confidence interval.

Final models of total 25(OH)D included a coat colour effect (P = 0.014, mean total 25(OH)D concentration 9.74 ng/ml 95% CI 1.78–17.70 higher in light than dark sheep), a positive anti-T. circumcincta IgE effect (p = 0.022), a negative anti-T. circumcincta IgG effect (p = 0.043), and an effect of age group (p < 0.001). All other terms were non-significant including faecal egg count (FEC) and were dropped from the model (Table 1).

Table 1. Results of regression models of 25(OH)D components including likelihood ratio test (LRT) p-values, estimates and standard error of estimate in brackets.

| Total 25(OH)D | 25(OH)D2 | 25(OH)D3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final model | Coat colour (light vs dark) | P = 0.014 9.744 (4.008) | – | P = 0.014 8.112 (3.323) |

| IgE | P = 0.022 38.848 (12.764) | P = 0.003 8.755 (2.964) | – | |

| IgG | P = 0.043 −18.679 (9.460) | – | ||

| Weight | – | P = 0.046 0.451 (0.229) | – | |

| Age Group (adult vs lamb) (geriatric vs lamb) | p < 0.001 36.706 (4.787) 25.937 (6.263) | p < 0.001 3.093 (2.592) -4.563 (3.518) | p < 0.001 29.250 (3.681) 27.002 (4.799) | |

| Dropped terms | Coat colour | – | P = 0.680 | – |

| IgE | – | — | P = 0.080 | |

| IgG | – | P = 0.227 | P = 0.792 | |

| Weight | P = 0.870 | – | P = 0.545 | |

| Addition of FEC to model using only Age Group | P = 0.123 | P = 0.224 | P = 0.161 |

LRT of addition of previous dropped terms and addition of faecal egg count to a model using only age group are shown in the lower sections.

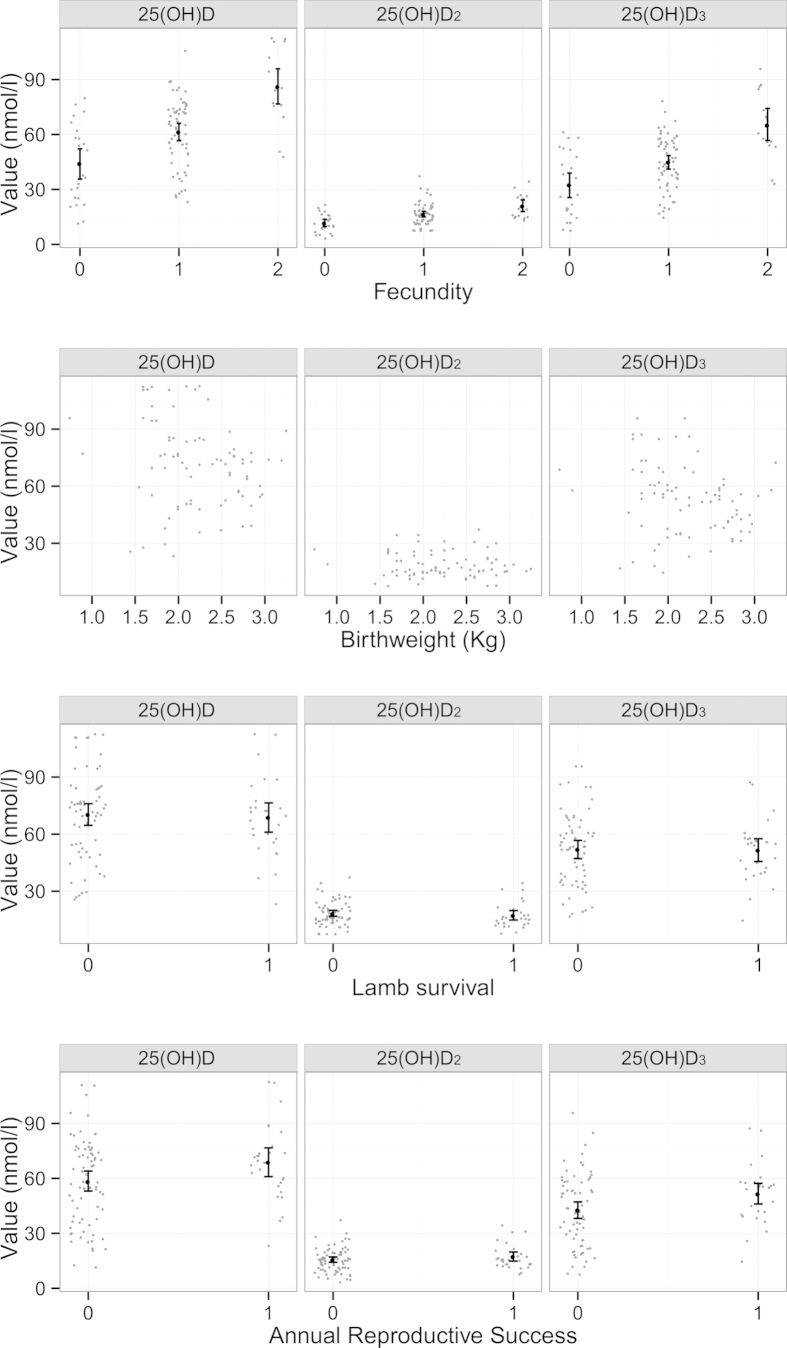

Vitamin D status in August 2012 strongly predicted a female’s fecundity the following spring, but not lamb birth weight or lamb survival over the following 12 months (Fig. 6; Table 2). However, the fecundity effect alone meant that females with higher summer total vitamin D levels had a greater annual reproductive success (i.e. more lambs surviving to one year of age; Fig. 6; Table 2). Our final proportional odds regression model of female fecundity, prior to inclusion of Vitamin D measures, included only age group and IgETc (p = 0.008 & p = 0.009), as August weight and female coat colour did not improve model explanatory power once age was included (Table 2). Independent of age, 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 or total 25(OH)D added separately to the model all improved model fit and positively predicted fecundity (p = 0.007, p < 0.001 & p < 0.001; Fig. 6, Table 2). Relaxing the assumption of proportional odds in each of these models did not result in a significant change in model fit, suggesting the assumption was supported (p = 0.394, p = 0.298 & p = 0.270 for 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D total models respectively).

Figure 6. Association between fecundity (number of lambs born), Birthweight, Lamb survival to 4 months of age (conditional on birth) and Annual reproductive success and serum concentrations of total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3.

Points are randomly ‘jittered’ on the horizontal axis, to separate points, for all variables except for birth weight.

Table 2. Results from regression models of fecundity, annual reproductive success, lamb birthweight and lamb over winter survival showing LRT p-values, estimates and (standard errors).

| Fecundity | Annual reproductive success | Birthweight | Lamb survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final model | Age group | p = 0.008 Adult: 1.41 (0.56) Geri: 0.16 (0.72) | P < 0.001 Adult: 0.755 (0.152) | ||

| IgETc | p = 0.009 3.03 (1.19) | ||||

| Lamb sex | p = 0.016 Female: 0.187 (0.078) | ||||

| Twin | P < 0.001 Twin: −0.661 (0.080) | ||||

| Birthweight | p = 0.002 1.606 (0.571) | ||||

| Dropped terms | Age group | p = 0.073 | p = 0.936 | ||

| Weight | p = 0.122 | p = 0.091 | |||

| Coat colour | p = 0.287 | p = 0.797 | p = 0.875 | ||

| IgETc | - | p = 0.368 | |||

| IgGTc | p = 0.292 | p = 0.345 | |||

| Lamb sex | p = 0.423 | ||||

| Twin | p = 0.489 | ||||

| Addition of 25(OH)D | 25(OH)D2 | p = 0.007 0.106 (0.040) | p = 0.245 | p = 0.670 | p = 0.403 |

| 25(OH)D3 | P < 0.001 0.066 (0.017) | p = 0.033 0.026 (0.013) | p = 0.621 | p = 0.893 | |

| Total 25(OH)D | P < 0.001 0.058 (0.014) | p = 0.045 0.020 (0.010) | p = 0.570 | p = 0.880 |

Lower sections show dropped terms from models (LRT p-values) and effect of adding 25(OH)D components to models (LRT p-values). Fecundity, lamb survival and annual reproductive success estimates are log odds ratios. Birth weight estimates are linear model coefficients.

Our final model of lamb birth weight included mother’s age group, lamb sex, and lamb twin status, while capture age and mother’s coat colour did not improve model fit and were thus dropped (Table 2). None of the maternal vitamin D measures explained additional variation in lamb birth weight when added to this model (p = 0.670, p = 0.621 & p = 0.570 for 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D models respectively). The final model for lamb first winter survival included only lamb birth weight; mother’s age group and coat colour and lamb sex and twin status did not explain additional variation (Table 2). None of the maternal vitamin D measures explained additional variation in lamb first winter survival when added to this model (p = 0.403, p = 0.893 & p = 0.880 for 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D models respectively). Finally, none of the terms tested were significant predictors of female annual reproductive success (ARS) (Table S2), but we found that total 25(OH)D and 25(OH)D3 significantly and positively predicted ARS when fitted along in the model (p = 0.245, p = 0.033 & p = 0.045 for 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D total models respectively; Fig. 6, Table 2). The effect size of 25(OH)D2 on ARS was of a similar magnitude but was not statistically significant (log odds ratio 0.039, 0.026 & 0.020 for 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D total respectively; Fig. 6).

Discussion

This study offers the first insight into the predictors of vitamin D status within an unmanaged animal population, and the first direct evidence of natural selection acting on circulating levels of vitamin D metabolites in the wild. We observed relationships between serum 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 concentrations and age, coat colour and anti-nematode IgE levels, which appear consistent with some previous findings from studies of humans and domestic animals5,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Strikingly, we observed a very strong relationship between total 25(OH)D levels in summer and a ewe’s fecundity the following spring (Fig. 6). There was no evidence that vitamin D predicted lamb birth weight or over-winter survival, but the fecundity effect alone was sufficient to result in significantly improved annual reproductive success in females with higher vitamin D concentrations (Fig. 6). There is an evident reproductive fitness advantage to females with improved vitamin D status, which our findings suggest is mediated by an association with fecundity rather than post-parturition maternal care. This constitutes important support for the role of vitamin D in mammalian reproductive performance, and the first direct observation of natural selection acting on vitamin D metabolism in the wild.

In wild Soay sheep, cutaneously produced vitamin D3 contributed considerably more to total 25(OH)D concentrations than orally consumed vitamin D2 during the summer. Previous studies of vitamin D in humans and domestic animals are frequently confounded by regular vitamin D supplementation, as well as potentially dramatic variation in diet and exposure to sunlight10,31. The unsupplemented and relatively homogeneous vegetable diet of Soay sheep on St Kilda means that they did not have access to dietary sources of vitamin D332. Thus, in our animals, all 25(OH)D3 must have been cutaneous in origin. It seems unlikely that variation in UV exposure can explain observed variation in 25(OH)D3 in Soay sheep, since there is a total lack of canopy cover on Hirta, and our samples were collected within a 2 week period in mid-summer. Our study therefore demonstrates that latitude alone is poor predictor of vitamin D3 status in wild animals; we have demonstrated that sheep of the same gender, coat colour and age living in a geographically constrained area can have wide fluctuations in serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that vitamin D3 status is highly predictive of subsequent fecundity and annual reproductive success when latitude is fixed and opportunities to modify exposure to UV radiation are limited.

Serum 25(OH)D3 concentrations in Soay sheep were predicted by coat colour, independent of age, which adds to existing evidence for associations between pigmentation and vitamin D metabolism21,22, as well as providing strongly suggestive evidence that vitamin D3 variation is under genetic control under natural conditions. It was recently established that in Soay sheep, the light/dark coat colour polymorphism is the result of a single base pair substitution at a single genetic locus, TYRP1, at which the dark allele is dominant to light23. The locus itself is known to be under complex natural selection, with homozygous dark sheep at an apparent fitness disadvantage33. The increased 25(OH)D3 concentrations in light sheep is consistent with previously observed associations between light skin or wool pigmentation and vitamin D status in humans and domestic sheep21,22,31. However, it also implies that the recessive allele responsible for light colouration has either direct or indirect effects on vitamin D metabolism and thus, to some degree at least, that genetic factors underpin 25(OH)D3 variation in our study population. Human twin studies have demonstrated that vitamin D status has a heritable component34, and recent genome wide association studies of circulating 25(OH)D concentrations identified several genes which influenced vitamin D status in humans8,9. Our study provides the first evidence suggesting that genetic variation exists in vitamin D status in a wild animal.

Variation in serum 25(OH)D2 concentrations in the Soay ewes sampled here was also noteworthy and could reflect altered grazing behaviour between individuals as well as genetic factors. We found evidence of a positive correlation between 25(OH)D2 concentrations and plasma levels of IgE immunoglobulin against T. circumcincta. Development of a robust IgE response is important in preventing T. circumcincta parasites becoming established in the gut of domestic sheep35,36,37, and there is good evidence that on St Kilda these parasites exert a considerable selective pressure on Soay sheep24. Positive correlations between vitamin D status and antigen specific IgE responses have also been reported in human studies25,26, and vitamin D supplementation has also been shown to increase IgE production to whole worm antigen in patients with Schistostoma haematobium infection30.Thus, it is possible that ewes with raised vitamin D2 and IgE levels may show improved resistance to gastrointestinal nematode parasites. However, previous work suggests broadly positive associations between anti- T. circumcincta IgE levels and Strongyle FEC in adult Soay ewes, consistent with antibody levels reflecting parasite exposure rather than resistance38. It is therefore also possible that the association between IgE and vitamin D2 is driven by spatial heterogeneity in both vegetation and exposure to Strongyle larvae. Our sample size was insufficient to meaningfully test how variation in habitat within Village Bay might influence vitamin D status, but this is an important avenue for future study.

Summer vitamin D status predicted annual reproductive success over the following year in female Soay sheep. Importantly, we were able to demonstrate that this was due to associations between vitamin D concentrations and fecundity, rather than with lamb birth weight or lamb first year survival rates. Previous work on domestic animals and rodent models supports a link between vitamin D status and both fecundity and reproductive performance traits16,17,39,40,41. Although the mechanisms responsible for the association between vitamin D status and female fecundity documented in Soay sheep remains unknown, the strength of the relationship – which is considerably stronger than observed for other potential predictors of fecundity, such as age and weight – in what is a relatively small sample, suggests important links between vitamin D metabolism and reproductive fitness exist in natural populations of animals. However, our study provides only a first glimpse of the potentially complex way in which natural selection acts on vitamin D status in the wild. We have considered only a single year’s reproductive performance across the life times of individual ewes that can live well over a decade under natural conditions. Whether and how vitamin D status relates to longevity or lifetime reproductive fitness remains to be determined. Furthermore, our samples come from a year when sheep numbers were low and conditions were relatively benign on Hirta. Both vitamin D status itself and its relationship with fitness may change dramatically with environmental conditions in different years. Our work provides the first evidence that vitamin D status has a genetic basis and is under selection in the wild. Further long-term studies in the wild can help elucidate how natural selection shapes and maintains genetic variation in vitamin D status.

Materials & Methods

Field and laboratory data collection

Since 1985, the sheep resident in the Village Bay area on the island of Hirta have been the subject of long term individual-based monitoring. These animals are completely unmanaged and unpredated and their reproductive life histories and survival rates are closely tracked throughout the year. Ewes typically produce a single lamb each spring, although around 18% produce twins. Fecundity is strongly influenced by age: Soay ewes are mature in their first year but fecundity in lambs is low and environment-dependent, while most prime age adults (1–6 years) produce lambs each year and fecundity declines as individuals senesce from 7 years onwards. Lambs are caught, weighed and tagged within a few days of birth in spring, and are then monitored closely for the rest of their lives. Every August as many sheep as possible in the Village Bay study area are captured using temporary traps and weights and blood and faecal samples are taken. Natural mortality occurs in late winter as a result of poor nutrition, challenging climate conditions and infection with parasites, particularly gastro-intestinal nematodes42,43. The population dynamic is characterised by periods of low and rising sheep numbers followed by dramatic ‘crash winters’ when greater than 60% of the population can perish (Fig. 2). Regular censuses and searches of the study area through the late winter and early spring period mean that the majority of carcasses are found, and death dates can be reliably assigned to study animals20.

In this study we used data and samples collected from 101 ewes caught in August 2012. The survival and reproductive performance of these ewes was monitored over the following two years. August 2012 directly followed a population crash over the winter of 2011/2012 (Fig. 2), and since sheep numbers were relatively low and there was very low mortality in winter 2012/2013: only 4 of 101 ewes died. 77 of the surviving ewes were fecund and produced 93 lambs in spring 2013 (16 twin pairs, 61 singletons), of which 83 were caught and weighed at birth. Lamb neonatal mortality in 2013 was very low (83 of the 93 lambs survived to August) but lamb over-winter mortality was high (only 28 of the 93 survived their first winter) due to harsh winter weather in late 2013 and early 2014.

Individuals captured in August 2012 were weighed, faecal sampled, and 9ml of whole blood was collected into a heparinised tube and a further 5 ml into a serum tube and both were stored at 4 °C. Nematode eggs in faecal samples were counted shortly after collection, and strongyle faecal egg count (FEC) was estimated as the number of eggs per gram using a modified McMaster technique44. On St Kilda, five nematode species contribute to this count, the most abundant being T. circumcincta, Trichostrongylus axei and Trichostrongylus vitrinus, and FEC has previously been shown to correlate with weight and over-winter survival prospects in our study population24,43. Within 24 hours of collection, heparinised tubes were centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m. (approx. 1500g) for 10 min and the plasma layer removed and stored at −20 °C. These plasma samples were used in ELISA antibody assays to quantify concentrations of anti-T. circumcinta third larval stage (L3) IgG and IgE as previously described38. Anti-T. circumcinta antibody levels have previously been related to FEC, adult survival and subsequent fecundity in this population38,45.

Serum tubes were centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m. (approx. 1500g) for 10 min, and the serum was removed and stored at −20 °C. Serum concentrations of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OHD3 were determined by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrophotometry (LC-MS/MS) using an ABSciex 5500 tandem mass spectrophotometer (Warrington, UK) and the Chromsystems (Munich, Germany) 25OHD kit for LC-MS/MS following the manufacturers’ instructions (intra- and inter-assay CV 3.7% and 4.8% respectively). This Supraregional Assay Service laboratory is accredited by CPA UK (CPA number 0865) and has been certified as proficient by the international Vitamin D Quality Assurance Scheme (DEQAS) (25). Total 25(OH)D is defined as the sum of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. Serum calcium concentrations were measured on an automated wet chemistry analyser (KoneLab 60i; Thermo Clinical Labsystems, Vantaa, Finland). Only 7 out of 99 sheep with electrolyte results had a serum calcium concentration below 2mmol/l demonstrating that hypocalcaemia was rarely diagnosed in our cohort.

All experiments had local ethical approval and were performed in accordance with UK legislation. The experimental protocols were approved by the University of Edinburgh Animal Welfare and Ethics Review Body.

Statistical analysis

We began by examining the distributions of our three vitamin D measures, and testing the difference in mean concentrations of 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 within samples, as well as their correlation (paired t-test, Pearson’s product moment correlation). We found a strong positive correlation between 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 concentrations (Fig. 3). In our analysis we examined total 25(OH)D and its two constituent measures separately in all further models. We first tested whether and how available phenotypic data predicted 25(OH)D status using separate linear models of total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. Since dramatic age-related variation in demographic rates, biometrics, immune and parasitological measures have been previously observed in Soay sheep, which characteristically show increases from lamb to adult (1–6 years) followed by senescent declines from 7 years onwards42,46,47, we began by examining age effects on vitamin D status. We fitted a smoother for age, implemented using a generalised additive model, and compared the fit of this unconstrained age function to models using our a priori expectation of a three-level age function comprising lamb, adult (1–6 years) and geriatrics (7 years or more) groups using AIC.

Having established that, as expected, age explained a considerable proportion of variation in all three vitamin D measures, and that our three-level age function adequately captured age-related variation (see Results), we proceeded to test additional effects in these models whilst retaining age group in all models. Since we did not have complete observations for FEC (88 observations) we tested this effect separately, comparing models of each vitamin D measure with accordingly restricted sample sizes which either excluded or included FEC, using likelihood ratio tests (LRTs). Since FEC did not significantly improved model fit, we proceeded, using a full data set, by adding August weight and anti-T. circumcincta IgG and IgE levels to models of total 25(OH)D, 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3. We simplified models by dropping each term in the model and removing the one producing the lowest LRT statistic, until only terms that were significant at the p < 0.05 level remained. We then checked for erroneous term deletions by separately adding each term back into the final model, and confirming this did not improve model fit using LRTs.

The relationship between candidate predictors and subsequent fecundity was investigated by treating ewe fecundity as an ordinal outcome (0, 1, or 2 lambs born the following spring). Previous studies have shown that ewe fecundity is strongly predicted by ewe age and, to a lesser degree, by her weight the previous August20. We used proportional odds logistic regression (POLR) to model the relationship between fecundity and candidate predictors. POLR models the ratio of the odds that an individual has a particular outcome compared to the next ‘lower’ outcome as being dependent on a linear combination of predicting variables. Here, the proportional odds assumption assumes that a change in covariates has the same impact on the odds ratio of producing two lambs vs. one lamb as it does on the odds ratio of producing one lamb vs. no lambs. This assumption simplifies the fitted model and if valid increases the precision of estimated relationships. The ordinal regression model’s assumptions can be relaxed, at the expense of inclusion of extra parameters, by allowing the influence of covariates to be different between no lambs and one lamb compared with one and two lambs. We tested the assumption of proportional odds by comparison with non-proportional odds models using a likelihood ratio test. In our initial POLR model we included age group, weight, coat colour, anti-T. circumcincta IgE and IgG. We excluded 25(OH)D from the initial model. This model was simplified using likelihood ratio tests as described earlier in the methods. We then added each individual vitamin D component into the final model to assess whether it added predictive value to the model using likelihood ratio tests.

Fecundity is only one aspect of a ewe’s annual reproductive success or fitness. Lamb birth weight has important fitness consequences, as it strongly predicts lamb survival which, in turn, has important consequences for both offspring and maternal reproductive fitness48. We therefore tested whether and how vitamin D status predicts lamb birth weight and lamb first winter survival. Birth weights were normally distributed and addressed using standard linear models. Previous work has demonstrated effects of capture age (in days), offspring sex, twin status and mother’s age on birth weight48. Therefore, we initially tested the effects of these terms, as well as mother’s coat colour and anti-T. circumcincta IgE levels (since they predicted 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 concentrations, respectively), on offspring birth weight, using the model simplification approach described above. Having determined a final model for birth weight, we separately added 25(OH)D2, 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D to the model to test their importance. Lamb neonatal survival rates were so high in our sample (89%) that they were not deemed worthy of further analysis, but first winter survival rates were relatively low (30%) and we therefore modelled winter survival as a binary variable (1 = survived, 0 = died) using generalised linear models with a binomial error distribution. We tested the same initial terms as in the birth weight models, except we substituted birth weight itself for capture age, and proceeded to test vitamin D measures against the final model as described for birth weight. Finally, we tested the overall effects of vitamin D on ewe annual reproductive success (ARS) – which we defined as the number of lambs produced by a female sheep which survived their first year of life. Since female ARS in our sample was either zero or one, we coded this as a binary variable and fitted a generalised linear model fitted with a binomial error distribution, but otherwise modelled this trait as we had done for fecundity. All models were fitted using the R statistical system.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Handel, I. et al. Vitamin D status predicts reproductive fitness in a wild sheep population. Sci. Rep. 6, 18986; doi: 10.1038/srep18986 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Trust for Scotland for their support and permission to work on St Kilda. We also thank the many volunteers and researchers involved in the course of the study. RJM was supported by a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship. The Soay sheep project is currently funded by NERC. DHN and KAW are funded by a BBSRC David Phillips research fellowship. The Roslin Institute is supported by an Institute Core Strategic Grant from the BBSRC.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed experiments : I.H., K.W., J.G.P., J.M.P., D.N. and R.J.M. Performed the experiments: I.H., K.W., J.G.P., J.M.P., A.M., P.S., T.M., J.B., D.C., D.N., R.J.M. Analysed the data: I.H., K.W., J.M.P., D.N. and R.J.M. Wrote and reviewed the paper: I.H., K.W., J.G.P., J.M.P., A.M., P.S., T.M., J.B., D.C., D.N. and R.J.M.

References

- Martineau A. R. et al. Neutrophil-mediated innate immune resistance to mycobacteria. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1988–1994 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascherio A., Munger K. L. & Simon K. C. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. The Lancet. Neurology 9, 599–612, 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70086-7 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolden-Kirk H., Overbergh L., Christesen H. T., Brusgaard K. & Mathieu C. Vitamin D and diabetes: its importance for beta cell and immune function. Mol. and cell. endo. 347, 106–120, 10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.016 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober U., Spitz J., Reichrath J., Kisters K. & Holick M. F. Vitamin D: Update 2013: From rickets prophylaxis to general preventive healthcare. Dermato-endo. 5, 331–347, 10.4161/derm.26738 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi A., Baddoura R., El-Rassi R. & El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Age but not gender modulates the relationship between PTH and vitamin D. Bone 47, 408–412, 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.002 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg M. K., Tandon N., Marwaha R. K., Menon A. S. & Mahalle N. The relationship between serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D, parathormone and bone mineral density in Indian population. Clin. endo. 80, 41–46, 10.1111/cen.12248 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcour A., Blocki F., Hawkins D. M. & Rao S. D. Effects of age and serum 25-OH-vitamin D on serum parathyroid hormone levels. J. clin. endo. and met. 97, 3989–3995, 10.1210/jc.2012-2276 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J. et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D levels. Hum. mol. gene. 19, 2739–2745, 10.1093/hmg/ddq155 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. J. et al. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 376, 180–188, 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60588-0 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M. F. Vitamin D deficiency. NEJM 357, 266–281 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen A. W. & Jablonski N. G. Vitamin D: in the evolution of human skin colour. Med. hypo. 74, 39–44, 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.08.007 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed M. L., Michos E. D., Post W. & Astor B. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch. int. med. 168, 1629–1637, 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1629 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba R. D. et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with greater all-cause mortality in older community-dwelling women. Nutr Res 29, 525–530, 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.07.007 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginde A. A., Scragg R., Schwartz R. S. & Camargo C. A. Jr. Prospective study of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality in older U.S. adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57, 1595–1603, 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02359.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk J., Torrealday S., Neal Perry G. & Pal L. Relevance of vitamin D in reproduction. Hum Reprod 27, 3015–3027, 10.1093/humrep/des248 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerchbaum E. & Obermayer-Pietsch B. Vitamin D and fertility: a systematic review. Euro. J. of endo. 166, 765–778, 10.1530/EJE-11-0984 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran B. P. & DeLuca H. F. Effect of vitamin D deficiency on fertility and reproductive capacity in the female rat. J. of nut. 110, 1573–1580 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa T. et al. Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor exhibit impaired bone formation, uterine hypoplasia and growth retardation after weaning. Nature genetics 16, 391–396, 10.1038/ng0897-391 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder C. J. & Bishop N. J. Rickets. Lancet 383, 1665–1676, 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61650-5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T. H. a. P., J. M. Soay sheep: dynamics and selection in an island population. (Cambridge University Press, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Harris S. S. & Dawson-Hughes B. Seasonal changes in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations of young American black and white women. Amer. J. Clin. Nut. 67, 1232–1236 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesby-O’Dell S. et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Amer. J. Clin. Nut. 76, 187–192 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratten J. et al. Compelling evidence that a single nucleotide substitution in TYRP1 is responsible for coat-colour polymorphism in a free-living population of Soay sheep. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274, 619–626, 10.1098/rspb.2006.3762 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward A. D. et al. Natural selection on a measure of parasite resistance varies across ages and environmental conditions in a wild mammal. J. evol. biol. 24, 1664–1676, 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02300.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. W., Kim J. H., Yoon J. H. & Kim C. H. The association between serum vitamin D level and immunoglobulin E in Korean adolescents. Inter. J. ped. otor. 78, 817–820, 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.02.021 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypponen E., Berry D. J., Wjst M. & Power C. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and IgE - a significant but nonlinear relationship. Allergy 64, 613–620, 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01865.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitt E., Sprenger-Mahr H., Knoll F., Neyer U. & Lhotta K. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with poor response to active hepatitis B immunisation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Vaccine 30, 931–935, 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.086 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha M. K. et al. Effect of 25-hydroxyvitamin D status on serological response to influenza vaccine in prostate cancer patients. The Prostate 71, 368–372, 10.1002/pros.21250 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine G. et al. Efficient tetanus toxoid immunization on vitamin D supplementation. Euro. J. Clin. Nut. 65, 329–334, 10.1038/ejcn.2010.276 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyman J. R., de Sommers K., Steinmann M. A. & Lizamore D. J. Effects of calcitriol on eosinophil activity and antibody responses in patients with schistosomiasis. Euro. J. Clin. Pharm. 52, 277–280 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. S. & Wright H. Relative contributions of diet and sunshine to the overall vitamin D status of the grazing ewe. Vet. Record. 115, 537–538 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japelt R. B. & Jakobsen J. Vitamin D in plants: a review of occurrence, analysis, and biosynthesis. Front. in plant sci. 4, 136, 10.3389/fpls.2013.00136 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratten J. et al. A localized negative genetic correlation constrains microevolution of coat color in wild sheep. Science 319, 318–320, 10.1126/science.1151182 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. et al. Genetic contribution to bone metabolism, calcium excretion, and vitamin D and parathyroid hormone regulation. J. Bone Min. Res. 16, 371–378, 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.2.371 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly T. N., Devaney E. & Matthews J. B. Teladorsagia circumcincta in the sheep abomasum: defining the role of dendritic cells in T cell regulation and protective immunity. Paras. immuno. 31, 347–356, 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01110.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy L. et al. Genetic variation among lambs in peripheral IgE activity against the larval stages of Teladorsagia circumcincta. Parasitology 137, 1249–1260, 10.1017/S0031182010000028 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stear M. J., Park M. & Bishop S. C. The key components of resistance to Ostertagia circumcincta in lambs. Parasitol Today 12, 438–441 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussey D. H. et al. Multivariate immune defences and fitness in the wild: complex but ecologically important associations among plasma antibodies, health and survival. Proc. Royal. Soc. 281, 20132931, 10.1098/rspb.2013.2931 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey J. D., Hines E. A., Starkey J. D., Starkey C. W. & Chung T. K. Feeding 25-hydroxycholecalciferol improves gilt reproductive performance and fetal vitamin D status. J. Anim. Sci. 90, 3783–3788, 10.2527/jas.2011-5023 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brommage R. & DeLuca H. F. Vitamin D-deficient rats produce reduced quantities of a nutritionally adequate milk. Amer. J. Physio. 246, E221–226 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marya R. K., Saini A. S., Lal H. & Chugh K. Effect of vitamin D supplementation in lactating rats on the neonatal growth. Ind. J of Physiol. Pharm. 35, 170–174 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson T. et al. Age, sex, density, winter weather, and population crashes in Soay sheep. Science 292, 1528–1531, 10.1126/science.292.5521.1528 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig B. H., Pilkington J. G. & Pemberton J. M. Gastrointestinal nematode species burdens and host mortality in a feral sheep population. Parasitology 133, 485–496, 10.1017/S0031182006000618 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulland F. M. & Fox M. Epidemiology of nematode infections of Soay sheep (Ovis aries L.) on St Kilda. Parasitology 105 (Pt 3), 481–492 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward A. D. et al. Heritable, heterogeneous, and costly resistance of sheep against nematodes and potential feedbacks to epidemiological dynamics. Ameri. Nat. 184 Suppl 1, S58–76, 10.1086/676929 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward A. D., Wilson A. J., Pilkington J. G., Pemberton J. M. & Kruuk L. E. Ageing in a variable habitat: environmental stress affects senescence in parasite resistance in St Kilda Soay sheep. Proc. Roy. Soc. 276, 3477–3485, 10.1098/rspb.2009.0906 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussey D. H., Watt K., Pilkington J. G., Zamoyska R. & McNeilly T. N. Age-related variation in immunity in a wild mammal population. Aging cell 11, 178–180, 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00771.x (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. J. et al. Selection on mothers and offspring: whose phenotype is it and does it matter? Evolution 59, 451–463 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]