Abstract

Invasion of ocean surface waters by anthropogenic CO2 emitted to the atmosphere is expected to reduce surface seawater pH to 7.8 by the end of this century compromising marine calcifiers. A broad range of biological and mineralogical mechanisms allow marine calcifiers to cope with ocean acidification, however these mechanisms are energetically demanding which affect other biological processes (trade-offs) with important implications for the resilience of the organisms against stressful conditions. Hence, food availability may play a critical role in determining the resistance of calcifiers to OA. Here we show, based on a meta-analysis of existing experimental results assessing the role of food supply in the response of organisms to OA, that food supply consistently confers calcifiers resistance to ocean acidification.

Increased CO2 derived from anthropogenic emissions is causing a decrease in surface ocean pH1,2,3, carbonate ion concentration ([CO32−]) and saturation states of calcite and aragonite3, which are predicted to affect the acid–base status and energy budgets of marine organisms4,5,6. Predicted impacts of low pH are particularly severe for marine organisms with carbonate skeletons7,8,9, where calcification is significantly affected by a reduction of carbonate ion concentration10. However, some recent studies question the importance of the reduction of carbonate ion concentration11 and show the importance of other carbonate system species (i.e. HCO3−) during calcification12. Ocean acidification (OA) experiments consistently show a decline in the rate of calcification at CO2 and pH levels expected by the end of the century, although with considerable variability in the responses7,8,9. Calcifiers can respond to critical environmental stress, as low pH, through metabolic changes, development of protective membranes, and by enhancing the activity of proton and calcium pumps among others5. Most of these physiological processes are energy demanding, implying that the vulnerability of calcifiers to low pH seawater may depend on their energetic status4,5,6 and, therefore, be affected by food availability13. Hence, food availability may play a critical role in determining the resistance of calcifiers to OA13. Yet, 51% of the laboratory experiments testing responses of larvae, juveniles and adults of calcifying animals to OA included in a recent meta-analysis9 did not supply food to the animals during the experiments. These studies included experiments testing OA effects on mollusks14 and corals15, echinoderms16 and crustaceans17. This practice is contrary to proposed to best practices for experiments evaluating biological responses to OA18, which recommends that food supply mimicking those in natural conditions should be provided to ensure that the results of OA experiments and conclusions be applicable to natural systems and to avoid additional stress to specimens tested.

To date, the role of food supply on the response of marine calcifiers to OA has been assessed by a limited number of experiments. Accordingly, none of the meta-analyses conducted to-date did address the possible role of food supply on calcifiers7,8,9, including the meta-analysis9 used as a basis to evaluate the likelihood of impacts of OA in the recent AR5 assessment of the IPCC19. Here we test the hypothesis that food supply consistently confers resistance to marine calcifiers against OA. We do so based on a meta-analysis of reported results from experiments assessing the role of food availability on the growth and calcification of calcifying animals exposed to OA conditions.

Results

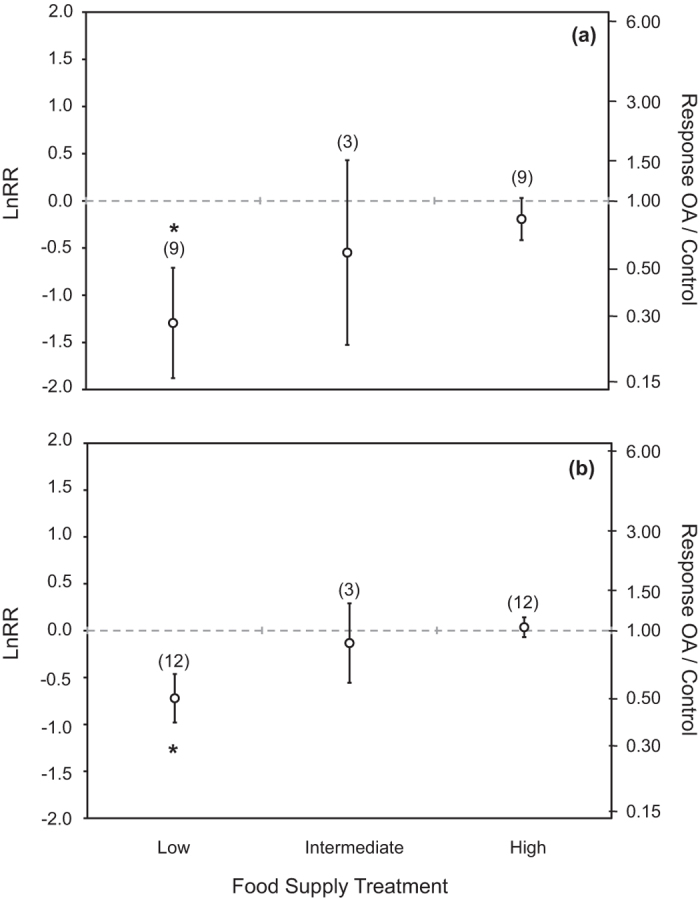

A total of 12 published reports, most published very recently were found that experimentally assessed the effect of food supply on calcification and growth of marine calcifying animals, including echinoderms, crustaceans, molluscs and coral species under OA conditions. However, the limited number of studies available as yet precluded the examination of phylogenetic or ontogenetic differences, as our meta-analysis only encompassed 11 different species (Table S1). A total of 45 growth-responses observations and 35 calcification- responses observations were analyzed. Significant heterogeneity among effects sizes for calcification response (QT = 1056.50, d.f. = 34, p < 0.0001) and growth response (QT = 1471.42, d.f. = 44, p < 0.0001) were detected. The magnitude of the effects varied among food treatments for both growth (QM 1,43 = 31.92, p < 0.0001) and calcification (QM 1,33 = 13.81, p = 0.0002). In addition, there was a significant decrease in the effect size for calcification responses with increasing pH decline between control and acidification treatment under high food supply, providing evidence of a significant decline in calcification rates when pH was experimentally reduced by > 0.6 pH units under high food supply (QM 1,33 = 6.46, p = 0.011, Table S2, Fig. S1). In contrast, the effect size for growth response was independent of the magnitude of the experimental reduction in pH (QM 1,43 = 0.86, p = 0.353) for any food treatment (Table S2, Fig. S1). Food supply increased the resistance of marine calcifying animals to low pH for both processes (calcification and growth) examined (Fig. 1). OA conditions caused a significant reduction in calcification of 56.1 ± 10.8% relative to that at present pH when food was supplied at low level (Mann-Whitney U-test, p < 0.05) as opposed to statistically insignificant (Mann-Whitney U-test, p > 0.05) reductions of 27.5 ± 22.7% at intermediate food supply and a moderate 10.0 ± 11.7% decline at high food supply (Table 1). Increased levels of food supply also alleviated growth suppression under reduced pH, and no significant decline in growth was found when food supply was provided at intermediate or high concentrations (Table 1, Fig. 1). Whereas growth of calcifying organisms was reduced by 45.2 ± 5.3% (Mann-Whitney U-test, p < 0.05) when the animals were exposed to low pH and low levels of food supply, their growth rate tended to increase by 6.6 ± 6.5% (Mann-Whitney U-test, p > 0.05) under high food supply in acidified treatments (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Figure 1. Mean effect size (LnRR) and response: control ratio of ocean acidification and food availability on calcification.

(a) and growth (b). Significance is determined when the 95% confidence interval does not cross zero. The number of experiments used to calculate the mean is included in parentheses. *denotes a significant effect.

Table 1. Growth and calcification under acidified conditions relative to present pH and food supply levels.

| Biological Variable | Food Supply Treatment |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Intermediate | High | |

| Calcification | 43.9 ± 10.8%(*) | 72.5 ± 22.7%(NS) | 90.0 ± 11.7%(NS) |

| Growth | 54.8 ± 5.3%(*) | 92.0 ± 15.0%(NS) | 106.6 ± 6.5%(NS) |

Data are mean ± SE percent relative to control. Ho no difference from control (percent = 100%): NS = p > 0.05, * p < 0.05.

Discussion

Although to date only 12 studies have assessed the role of food supply on OA effects over calcifiers species, our results confirm that food supply reduces the impacts of experimental ocean acidification on the growth and calcification rates of a range of marine organisms including corals, molluscs, crustaceans and echinoderms. Whereas the number of assessments of the role of food supply on the performance of calcifiers under experimental ocean acidification conditions is still limited, the analysis suggests that marine calcifiers might be more resistant to ocean acidification than portrayed by existing assessments, based on meta-analysis including a large proportion of experiments were the organisms were not fed. In addition, our results suggest that forecasting the future of marine calcifiers requires consideration of both expected changes in carbonate chemistry and the productivity regimes of the ecosystems. Based on our analysis, the hypothesis that food supply confers marine calcifiers resistance against ocean acidification seems to hold. Although there seems to be an upper limit to this increased resistance as even organisms receiving high food supply may become vulnerable to OA when pH would decline by more than 0.6 units.

These findings are consistent with our understanding of the mechanisms allowing marine calcifiers to promote bio-calcification, a process mainly under biological control20, under the adverse conditions associated with OA. These mechanisms include the use of macromolecules (i.e. organic matrix proteins), proton and calcium pumps and the formation of membranes favoring aragonite or calcite deposition21,22,23,24. Some corals and foraminifera are able to increase pH at the site of calcification while some decapods, cephalopods and fishes can accumulate HCO3− in extracellular fluids, thus buffering the negative impacts of hypercapnia and promoting calcification even under adverse conditions5. Bivalves lack the capacity to pump HCO3− to increase pH within hemolymp or extrapallial fluid in order to avoid a decrease of pH at calcification sites25. Accordingly, the poor capacity of bivalves to regular their acid-base status has been inferred to render them particularly sensitive to the changes in the seawater carbon system involved in OA26. Nevertheless, bivalves exhibit a suite of mechanisms to cope with adverse pH environmental conditions to calcify, such as increased ammonia excretion, intracellular release of inorganic molecules and ions (i.e. CaCO3) and the presence of organic layers (i.e. periostracum or the shell organic matrix) guiding carbonate crystal deposition27,28,29,30,31. Although some of these mechanisms (i.e. capacity to increase pH at the site of calcification in corals) appears to be a particularly energy-efficient way to cope with pH variability32, the most of these processes are metabolically demanding, especially protein synthesis to generate the organic matrix of the shell33,34,35. Indeed, calcification processes have been reported to require 75% of the energy invested in somatic growth and 410% of that invested in reproduction by calcifying organisms such as echinoderms36. Food supply, thus, becomes significantly important in order to supply the energy required to support the metabolic processes facilitating bio-calcification under normal and specifically under adverse conditions associated with ocean acidification5.

The hypothesis that food supply confers marine calcifies resistance to OA is consistent with the current understanding of the energetic requirements of marine animals. It also would explain the apparent paradox that many upwelling areas around the world support some of the highest commercial fisheries of bivalves37,38 despite being frequently invaded by corrosive waters with pH even below the average pH in ocean surface waters expected by 21003,39. Upwelling areas are characterized by very high primary production driven by the high-nutrients of upwelled waters40 and, hence, food supply, thereby conferring resistance to cope with their corrosive waters to calcifiers. However, the existence of lag of a few days between the upwelling of CO2–rich waters and peak primary productivity41 requires the presence of biological and evolutionary mechanisms (i.e. phenotypic plasticity) of calcifiers to cope with adverse conditions prior to increase food supply5,42,43. Hence, whereas high food supply certainly helps calcifiers support their characteristic high productivity in upwelling regions, this also requires local adaptations to cope with the adverse conditions the organisms experience immediately following upwelling events.

Our results show that caution should be taken to only base predictions of the response of calcifying organisms to future OA on pH or CO2 alone and that the role of concurrent changes in primary production should also be considered. For instance, the impact of OA on tropical and subtropical calcifiers, such as coral reefs, may be enhanced by parallel oligotrophication of the subtropical ocean driven by warming44. In contrast, over large spans of the Arctic Ocean, considered to be the ocean closest to experiencing corrosive conditions, warming and the loss of sea ice may lead to increased primary production45,46, possibly enhancing food supply, thus a possible increase in the resistance of Arctic calcifiers to OA. To date the expected response of Arctic pelagic calcifiers to OA is based solely on experiments with the pteropod Limacina47,48,49 conducted without offering food supply, possibly conducive to a perception of high vulnerability of these organisms compared to that they would experience under natural conditions and levels of food. Hence, concerted future trajectories in OA and food supply should be considered to formulate robust forecasts of the responses of marine calcifiers beyond speculations based on changes in one component alone.

Our analyses demonstrate the importance of OA experiments to adhere to best practices guidelines18 by providing adequate food levels when testing animals. The results point to the fact that failure to provide food to marine calcifiers can increase their vulnerability to OA in experimental assessments, which may yield inflated assessments of the impacts of OA on these organisms. Hence, the fact that more than half of the studies involving calcifying animals included in a recent meta-analysis9 did not supply food to the tested animals, may have lead to an overestimation of the impacts of OA on calcifying animals. This is of consequence as the results of that particular study were used as a basis to evaluate impacts of OA in the AR5 report of the IPCC19. Whereas the interaction between warming and OA has been addressed in the past9,50,51, models predicting the effect of OA on vulnerable marine calcifiers should also consider projected changes in food supply, which according to our results might act as main driver of the resistance of calcifiers to OA.

Methods

Bibliographic Search

We identified studies that measured any biological response to ocean acidification and included food supply treatments published to date. For the search, we used ISI web of science [v. 5.16.1©], the European Project on Ocean Acidification (EPOCA) blog (http://oceanacidification.wordpress.com/) and the updated bibliographic database from IAEA Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre (OA-ICC)52, as well cross-references of the bibliographies of identified articles. We used the following keywords: “ocean acidification”, “food supply”, “food availability” and combinations of these. To date, only 12 experimental studies have been published which have recorded both the effects of OA and food supply.

Data Extraction

We extracted the response of the investigated organism and/or process to the experimental OA treatments and the corresponding values of the control treatment. We used the experimental treatment with the highest pH and highest food supply level as control, and compared the results with any other treatment where pH was decreased and food supply was manipulated to different concentrations (high, intermediate and low food level). We followed the authors in ranking the food levels supplied. However, only five studies specifically justified the ecological relevance of the food levels supplied (see Table S1). In the case of low food treatments, this food treatment corresponded to a starvation regime in five of the 12 studies, while for the rest of the studies this treatment corresponded to food concentrations that reduced food considerably in comparison with that provided in the high food treatment. Provided the importance of food supply in the responses of marine calcifiers to OA, it is important that food supply be justified in relation to organismal requirements and the levels the organisms experience in the environment. When a single experiment reported several response variables that measured the same biological response, we included only one response per experiment to avoid pseudo-replication. When a biological response was measured repeatedly at different time intervals, we only considered the results for the final time point of exposure to experimental treatments. Calcification responses were primarily based on estimates of net calcification and skeleton weight while growth responses included estimates of change in biomass, length, cell volume and growth rates. There were insufficient data on other response variables such as metabolism, mortality and feeding rates to allow quantification of these effects. Data were extracted from tables, text and Pangaea® database. To obtain data from graphics we used the software GraphClick (version 3.0) (Neuchatel, Switzerland).

Data Analysis

Log-transformed response ratio (LnRR), which is the ratio of the mean effect in the acidification treatment to the mean effect in a control group53 was calculated. A log-transformed response ratio of zero is interpreted as the experimental treatment having no effect on the response variable, while a positive value indicates a positive effect and a negative value indicates a negative effect. The statistical significance of mean effect sizes is based on bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. When these 95% confidence intervals do not overlap zero, the effect size is considered significant (α = 0.05). In order to determine if there was variation of effect sizes magnitude among studies (heterogeneity) for both growth and calcification responses a QT (α = 0.05) statistic test was performed54. The variation in effect sizes among food treatments and ΔpH (reduction from control conditions) for all growth and calcification observations were tested using a random effects meta-analysis. Lastly, the relationship between differences in effects with the experimental pH change (ΔpH) was tested using linear regression for each food treatment. Additionally, effects of OA for each food supply treatment were calculated as a percentage related to control conditions (see above). Statistical differences in calcification and growth between control and experimental treatments were tested using a Mann-Whitney test. All of the analyses were performed using JMP software (Version 9.0.1) and R routines (metafor package) (R Development Core Team 2009).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ramajo, L. et al. Food supply confers calcifiers resistance to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 6, 19374; doi: 10.1038/srep19374 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency within the Danish 486 Cooperation for Environment in the Arctic (DANCEA), ASSEMBLE grant agreement no. 227799 from European Community and from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (ESTRESX, number CTM2012-32603). N.A.L. acknowledges support from grants Fondecyt 1140938 and NC 1200286 (Millennium Nucleus Project MUSELS) and L.R. was supported by BECAS CHILE fellowship program from Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica de Chile (CONICYT).

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.R., I.E.H., N.M., D.K.-J., M.K.S., M.E.B., N.A.L., Y.S.O. and C.M.D. conceived and designed the study, L.R., N.M. and E.P.-L. collected the data, L.R. and C.M.D. analyzed the results, and all authors contributed to writing the paper.

References

- Wolf-Gladrow D. A., Riebesell U., Burkhardt S. & Bijma J. Direct effects of CO2 concentration on growth and isotopic composition of marine plankton. Tellus B . 51, 461–476 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira K. & Wickett M. E. Anthropogenic carbon and ocean pH. Nature 425, 365 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feely R. A., Sabine C. L., Hernandez-Ayon J. M., Ianson D. & Hales B. Evidence for upwelling of corrosive “acidified” water onto the continental shelf. Science 320, 1490–1492 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood H. L., Spicer J. I. & Widdicombe S. Ocean acidification may increase calcification rates, but at a cost. Proc. R. Soc. B . 275, 1767–1773 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks I. E. et al. Biological mechanism supporting adaptation to ocean acidification in coastal ecosystems. Estuar Coast. Shelf Sci. 151, A1–A8 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Pan T. C. F., Applebaum S. L. & Manajan D. T. Experimental ocean acidification alters the allocation of metabolic energy. P. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA , 10.1073/pnas.1416967112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks I. E., Duarte C. M. & Alvarez M. Vulnerability of marine biodiversity to ocean acidification: a meta-analysis. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 89, 186–190 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker K. K., Kordas R. L. & Singh G. G. Meta-analysis reveals negative yet variable effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms. Ecol. Lett 13, 1419–1432 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker K. J. et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interactions with warming. Glob Change Biol. 19, 1884–1896 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser G. G. et al. Saturation-state sensitivity of marine bivalve larvae to ocean acidification. Nat Clim Change. 5, 273–280 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bach L. T. Reconsidering the role of carbonate ion concentration in calcification by marine organisms. Biogeosciences 12, 4939–4951 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Jury C. P., Whitehead R. F. & Szmant A. M. Effects of variations in carbonate chemistry on the calcification rates of Madracis auretenra (=Madracis mirabilis sensu Wells, 1973): bicarbonate concentrations best predict calcification rates. Glob Change Biol. 16, 1632–1644 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen J., Casties I., Pansch C., Körtzinger A. & Melzner F. Food availability outweighs ocean acidification effects in juvenile Mytilus edulis: laboratory and field experiments. Glob Change Biol. 19, 1017–1027 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay H. S., Kendall M. A., Spicer J. I., Turley C. & Widdicombe S. Novel microcosm system for investigating the effects of elevated carbon dioxide and temperature on intertidal organisms. Aquatic Biol 3, 51–62 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Putron S. J., de McCorkle D. C., Cohen A. L. & Dillon A. B. The impact of seawater saturation state and bicarbonate ion concentration on calcification by new recruits of two Atlantic corals. Coral Reefs 30, 321–328 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Wood H. I., Widdicombe S. & Spicer J. I. The influence of hypercapnia and the infaunal brittlestar Amphiura filiformis on sediment nutrient flux – will ocean acidification affect nutrient exchange? Biogeosciences 6, 2015–2024 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Findlay H. S., Kendall M. A., Spicer J. I., Turley C. & Widdicombe S. Novel microcosm system for investigating the effects of elevated carbon dioxide and temperature on intertidal organisms. Aquat Biol 3, 51–62 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe S., DuPont S. & Thorndyke M. Guide to best practices for ocean acidification research and data reporting (eds Riebesell U. et al.) Ch. 7, 113–122 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2010).

- Gattuso J.-P. et al. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Field C. B. et al.) Cross-chapter box on ocean acidification, 129–131 (Cambridge University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Addadi L. & Weiner S. Control and design principles in biological mineralization. Angewandte Chemie 31, 153–169 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy W. J., Taylor J. D. & Hall A. Environmental and biological controls on bivalve shell mineralogy. Biol. Rev. 44, 499e530 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. L. & McConnaughey T. Geochemical perspectives on coral mineralization. Rev. Min. Geochem . 54, 152–187 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Allemand D. et al. Biomineralisitation in reef-building corals: from molecular mechanism to environmental control. C. R. Pale 3, 453–467 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Elhadj S., De Yoreo J. J., Hoyer J. J. & Dove P. M. Role of molecular charge and hydrophilicity in regulating the kinetics of crystal growth. P. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19237–19242 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann A., Fietzke J., Melzner F., Bohm F., Thomsen J., Garbe-Schonberg D. & Eisenhauer A. Conditions of Mytilus edulis extracellular body fluids and shell composition in a pH-treatment experiment: acid-base status, trace elements and δ11B. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 13, Q01005 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Parker L. et al. Predicting the response of molluscs to the impact of ocean acidification. Biology 2, 651–692 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Reiriz M. J., Range P., Álvarez-Salgado X. A., Espinosa J. & Labarta U. Tolerance of juvenile Mytilus galloprovincialis to experimental seawater acidification. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 454, 65–74 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Akberali H. B. 45Calcium uptake and dissolution in the shell of Scrobicularia plana (da Costa). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 43, 1–9 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfo-Metalpa R. et al. Coral and mollusc resistance to ocean acidification adversely affected by warming. Nat Clim Change 1, 308–312 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser G. G. & Salisbury J. E. Ocean Acidification in the Coastal Zone from an Organism’s Perspective: Multiple System Parameters, Frequency Domains, and Habitats. Ann Rev Mar Sci 6, 221–247 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. A., Jones M. E., Boudreau C. L., More R. L. & Westman B. A. Dissolution mortality of juvenile bivalves in coastal marine deposits. Limnol Oceanogr 49, 727–734 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch M. T., Falter J., Trotter J. & Montagna P. Coral resilience to ocean acidification and global warming through pH up-regulation. Nat Clim Change 2, 623–627 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A. R. Relative cost of producing skeletal organic matrix versus calcification: evidence from marine gastropods. Mar Biol 75, 287–292 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A. R. Calcification in marine molluscs: how costly is it ? P. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 1379–1382 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser G. G. et al. A developmental and energetic basis linking larval oyster shell formation to ocean acidification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2171–2176 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Paine R. T. A short-term experimental investigation of resource partitioning in a New Zealand rocky intertidal habitat. Ecology 52, 1096–1105 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Pauly D. & Christensen V. Primary production required to sustain global fisheries. Nature 374, 255–257 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Bakun A. Global climate change and intensification of coastal ocean upwelling. Science 247, 198–201 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte C. M. et al. Is ocean acidification an open-ocean syndrome ? Understanding anthropogenic impacts on marine pH. Estuar Coast 36, 221–236 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst A., Sathyendranath S., Platt T. & Caverhill C. An estimate of global primary production in the ocean from satellite radiometer data, J Plankton Res 17, 1245–1271 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Figueiras F. G., Labarta U. & Fernández-Reiriz M. J. Coastal upwelling, primary production and mussel growth in the Rías Baixas of Galicia. Hydrobiologia 484, 121–131 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Calosi P. et al. Adaptation and acclimatization to ocean acidification in marine ectotherms: an in situ transplant with polychaetes at a shallow CO2 vent system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci . 368, (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramajo L., Rodriguez-Navarro A., Duarte C. M., Lardies M. A. & Lagos N. A. Shifts in shell mineralogy and metabolism of Concholepas concholepas juveniles along the Chilean coast. Mar Freshwater Res 66, 1147–1157 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lo-Yat A. et al. Extreme climatic events reduce ocean productivity and larval supply in a tropical reef ecosystem. Glob Change Biol 17, 1695–1702 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fortier M., Fortier L., Michel C. & Legendre L. Climatic and biological forcing of the vertical flux of biogenic particles under seasonal Arctic sea ice. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 225, 1–16 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Slagstad D., Ellingsen I. H. & Wassmann P. Evaluating primary and secondary production in an Arctic Ocean void of summer sea ice: An experimental simulation approach. Progr Oceanogr 90, 117–131 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Comeau S., Jeffree R., Teyssié J.-L. & Gattuso J.-P. Response of the Arctic Pteropod Limacina helicina to Projected Future Environmental Conditions. PLoSOne 5, e11362, 10.1371/journal.pone.0011362 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka S., Buedenbender J.,. Boxhammer T., Riebesell U. & Büdenbender J. Impact of ocean acidification and elevated temperatures on early juveniles of the polar shelled pteropod Limacina helicina: mortality, shell degradation, and shell growth. Biogeosciences . 8, 919–932 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Lischka S. & Riebesell U. Synergistic effects of ocean acidification and warming on overwintering pteropods in the Arctic. Glob Change Biol 18, 3517–3528 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gruber N. Warming up, turning sour, losing breath: ocean biogeochemistry under global change. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A . 369, 1980–96 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey B. P., Gwynn-Jones D. & Moore P. J. Meta-analysis reveals complex marine biological responses to the interactive effects of ocean acidification and warming. Ecol Evol 3, 1016–1030 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatusso J.-P. & Hansson L. Ocean acidification (eds Gatusso J.-P. & Hansson L.) (Oxford University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L. V., Gurevitch J. & Curtis P. The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80, 1150–1156 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L. V. & Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis (eds Hedges L. V. & Olkin I.) Ch. 6, 108–148 (Academic Press, 1985). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.