Abstract

Apart from its role in MHC class I antigen processing, the immunoproteasome has recently been implicated in the modulation of T helper cell differentiation under polarizing conditions in vitro and in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases in vivo. In this study, we investigated the influence of LMP7 on T helper cell differentiation in response to the fungus Candida albicans. We observed a strong effect of ONX 0914, an LMP7-selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome, on IFN-γ and IL-17A production by murine splenocytes and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated with C. albicans in vitro. Using a murine model of systemic candidiasis, we could confirm reduced generation of IFN-γ- and IL-17A-producing cells in ONX 0914 treated mice in vivo. Interestingly, ONX 0914 treatment resulted in increased susceptibility to systemic candidiasis, which manifested at very early stages of infection. Mice treated with ONX 0914 showed markedly increased kidney and brain fungal burden which resulted in enhanced neutrophil recruitment and immunopathology. Together, these results strongly suggest a role of the immunoproteasome in promoting proinflammatory T helper cells in response to C. albicans but also in affecting the innate antifungal immunity in a T helper cell-independent manner.

The 26S proteasome is a multicatalytic enzyme expressed in the nucleus and cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells. It is responsible for the degradation of the bulk (80–90%) of cellular proteins thereby regulating many biological processes including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen presentation1,2,3. In response to the proinflammatory cytokine interferon (IFN)-γ, the catalytically active β subunits of the proteasome are replaced by their inducible counterparts low molecular mass polypeptide (LMP)2 (β1i), multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like (MECL)-1 (β2i), and LMP7 (β5i), building the so-called immunoproteasome4,5. The incorporation of the inducible subunits leads to minor structural changes within the proteasome, to a marked change in the cleavage site preference, and to an enhanced production of T cell epitopes4,6. However, it has been demonstrated that immunoproteasomes do not only play an important role in MHC class I antigen processing but also in shaping the naive T cell repertoire in the thymus and regulating immune responses in the periphery7,8. ONX 0914 (formerly named PR-957), an LMP7-selective epoxyketone inhibitor of the immunoproteasome, reduced cytokine production in activated monocytes or lymphocytes in vitro and attenuated disease progression in various mouse models of autoimmune diseases7,9,10,11,12,13,14. Moreover, selective inhibition of LMP7 was shown to suppress the development of T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 cells and to promote regulatory T (Treg) cell generation under polarizing conditions in vitro9,11

Candida albicans is a commensal organism of mucosal and skin surfaces which can cause various disease manifestations ranging from oral or mucocutaneous to lethal disseminated candidiasis in immunocompromised hosts15,16. Host protection from infection ultimately depends on the recognition of C. albicans by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their associated signalling pathways that initiate antifungal immunity. C. albicans is a strong inducer of Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation by the engagement of C-type lectins on the surface of antigen presenting cells and the subsequent induction of cytokines like interleukin (IL)-6, IL-12, IFN-γ, and IL-2317,18,19,20. Th1 cells provide fungal control through IFN-γ production required for optimal activation of phagocytes and for helping in the generation of a protective antibody response21. Th17 cells act as an important source of IL-17A which is crucial for the anti-C. albicans host defence by inducing the expression of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides, as well as by promoting granulopoiesis and recruiting neutrophils to the site of infection19,22,23. Despite adaptive immunity being important for host defence against mucocutaneous candidiasis, it does not play a prominent role in combatting disseminated C. albicans infection. Instead, innate immunity acts as the major barrier to systemic Candida spread. The candidacidal activity of neutrophils is the key mediator of immunity to systemic candidiasis and neutropenia is a major risk factor for invasive candidiasis24,25. As in humans, the mouse kidney is the primary target organ during systemic C. albicans infection and progressive sepsis as well as renal failure account for mortality in that model26,27,28. Since the severity of kidney damage is quantitatively related to the levels of host innate immune responses, it has been suggested that uncontrolled inflammation and subsequent immunopathology, rather than C. albicans itself, may worsen disease outcome. Indeed, massive infiltration of neutrophils is commonly observed and believed to contribute significantly to host tissue destruction29,30,31.

Here, we found that ONX 0914 treatment blocks Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation in response to C. albicans in vitro and in a murine model of systemic candidiasis in vivo. Interestingly, ONX 0914 treated mice displayed an enhanced susceptibility at early stages of infection implicating a so far undescribed influence of LMP7 inhibition on innate anti-C. albicans immune responses.

Results

Reduced C. albicans-induced production of IL-17A and IFN-γ by murine splenocytes and human PBMCs in vitro

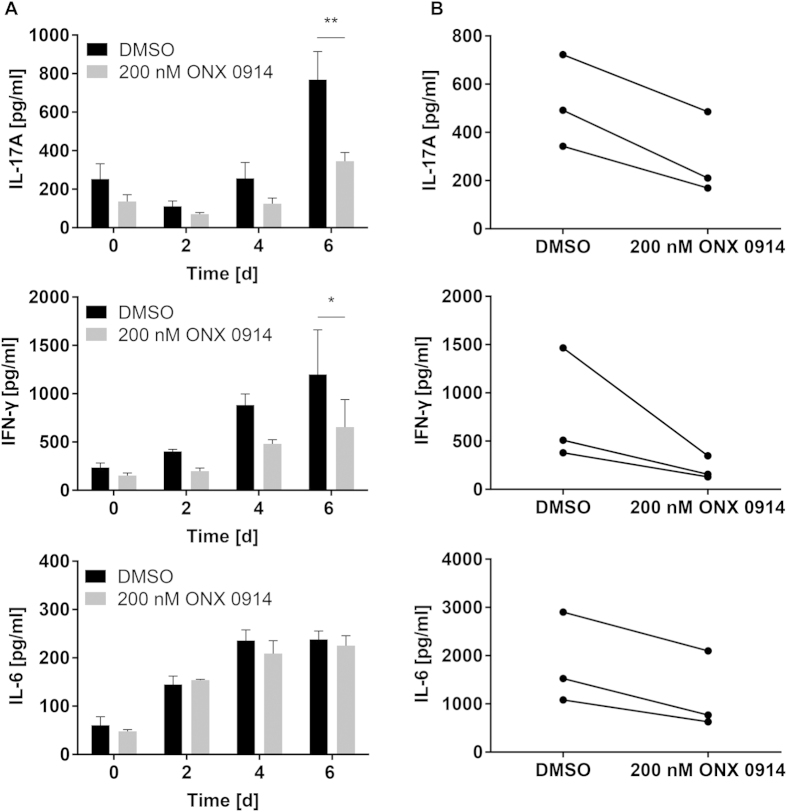

Hitherto, the inhibition of LMP7 has been shown to suppress several autoimmune diseases which correlated with a reduction in the differentiation of pathogenic Th1 and Th17 cells. Since Th1 and especially Th17 cells play a central role in the host defence against C. albicans, we investigated the impact of immunoproteasome inhibition on the immune response against this pathogen. In a first approach, we stimulated naive splenocytes with heat-killed C. albicans yeast in vitro, leading to IL-17A and IFN-γ release into the culture supernatant. Compared to cells treated with DMSO, we observed reduced IL-17A and IFN-γ production by splenocytes pulsed with 200 nM ONX 0914 (Fig. 1A). This effect was LMP7-dependent because ONX 0914 treatment of splenocytes from LMP7−/− mice did not lead to reduced cytokine production (Supplementary Fig. S1). In order to investigate whether LMP7 inhibition has a similar effect on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), PBMCs from healthy volunteers were stimulated with heat-killed C. albicans in vitro and cytokines were measured in the supernatant by ELISA. Similar to murine splenocytes, ONX 0914 treatment of human PBMCs resulted in reduced IL-17A and IFN-γ production in response to C. albicans (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the secretion of IL-6, a key cytokine for Th17 differentiation, was reduced in human PBMCs by LMP7 inhibition while it was not affected in murine splenocytes (Fig. 1A). Next, naive murine splenocytes were negatively sorted for CD4+ T cells and either the ‘antigen presenting cells’-containing fraction (splenocytes - CD4+ T cells) or the CD4+ T cell fraction was pulsed with 200 nM ONX 0914. Untreated and treated cell fractions were combined and stimulated with heat-killed C. albicans. IFN-γ and IL-17A production was also strongly reduced by ONX 0914 treatment of only the ‘antigen presenting cells’-containing fraction (splenocytes - CD4+ T cells) (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Similarly, the release of IFN-γ and IL-17A was reduced by treatment of the CD4+ T cell fraction, although not quite significant for IFN-γ (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Moreover, when splenocytes were stimulated with C. albicans in the presence of blocking antibodies to MHC-II, we observed a strong reduction of IL-17A (Supplementary Fig. S2C) indicating that IL-17A production is to a large degree dependent on MHC-II antigen presentation. These results indicate that ONX 0914 is able to block the production of proinflammatory cytokines by directly acting on CD4+ T cells as well as affecting ‘antigen presenting cells’.

Figure 1. Influence of ONX 0914 on C. albicans-induced production of IL-6, IL-17A, and IFN-γ by murine splenocytes and human PBMCs in vitro.

Culture supernatant levels of IL-6, IL-17A, and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA. (A) Naive murine splenocytes were pulsed with DMSO or 200 nM ONX 0914 for 2 h and cultured in the presence of heat-killed C. albicans yeast for up to 6 days. Data are representative for one out of three independent experiments and expressed as mean +/− SD. (B) Human PBMCs from healthy donors were treated as described in (A) and cultured in the presence of heat-killed C. albicans hyphae for 5 days. Data represent blood samples from three different donors. Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

Impaired generation of IL-17A- and IFN-γ- producing cells and aggravated clinical outcome of disseminated candidiasis in ONX 0914 treated mice

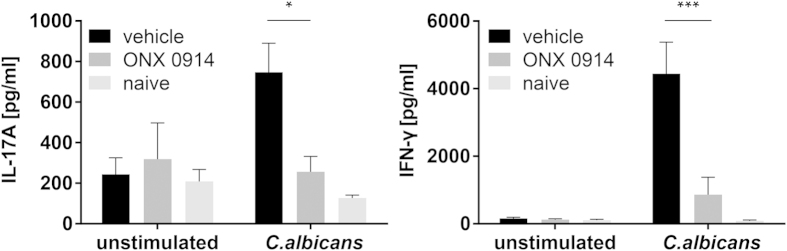

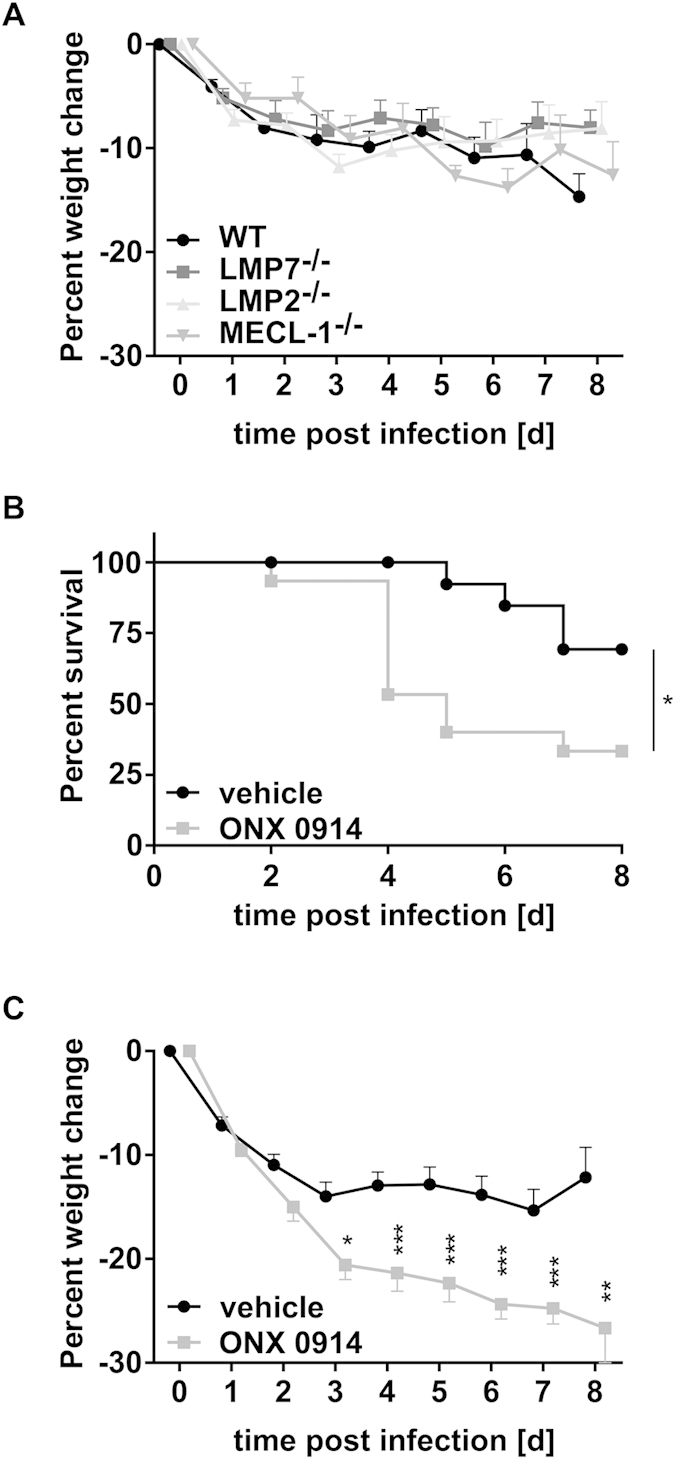

Our results obtained with splenocytes and PBMCs stimulated with C. albicans in vitro (Fig. 1) and previous reports suggest a role of LMP7 inhibition in T helper cell differentiation9,11,13. Thus, we intended to investigate whether the immunoproteasome has an influence on the generation or activation of IL-17A- and IFN-γ-producing cells in response to systemic C. albicans infection in vivo. Analyzing cytokine production of splenocytes upon ex vivo restimulation with heat-killed C. albicans on day 7 postinfection revealed a marked reduction of IL-17A and IFN-γ production upon LMP7 inhibition in vivo (Fig. 2). While immunoproteasome-deficient mice showed no altered susceptibility to invasive candidiasis (Fig. 3A), ONX 0914 treated mice suffered from accelerated and more pronounced weight loss as well as higher mortality compared to vehicle treated mice already on day 2 of infection (Fig. 3B,C). Moreover, in some experiments, we observed that LMP7 inhibition led to movement disorders and neurological abnormalities of mice as manifested by a slight tilting of the head and uncontrolled twisting/rotation when handled (data not shown).

Figure 2. LMP7 inhibition reduces the development of IL-17A and IFN-γ producing cells in vivo.

Mice were i.v. infected with 1 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) every second day. On day 7 postinfection, splenocytes were restimulated with 106/ml heat-killed C. albicans yeast cells for 48 h. Levels of IL-17A (left graph) and IFN-γ (right graph) were measured in the supernatant by ELISA. Data are representative for one out of three independent experiments and expressed as mean +/− SEM of n = 5 mice (n = 2 naive mice). Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA with *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3. Influence of the immunoproteasome on weight loss and survival in systemic candidiasis.

C57BL/6, LMP7−/−, LMP2−/−, and MECL-1−/− mice were i.v. infected with 1 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) every second day where indicated (B,C). (A,C) Change of body weight during systemic infection with C. albicans. Percent weight loss (y-axis) is plotted versus time (x-axis). Data points represent mean weight change +/− SEM. (B) Survival curves of ONX 0914 and vehicle treated mice. Data represent combined results from 2–3 experiments with n = 8–18 mice per group. Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Selective inhibition of LMP7 leads to increased fungal burden at early time points in the course of invasive candidiasis

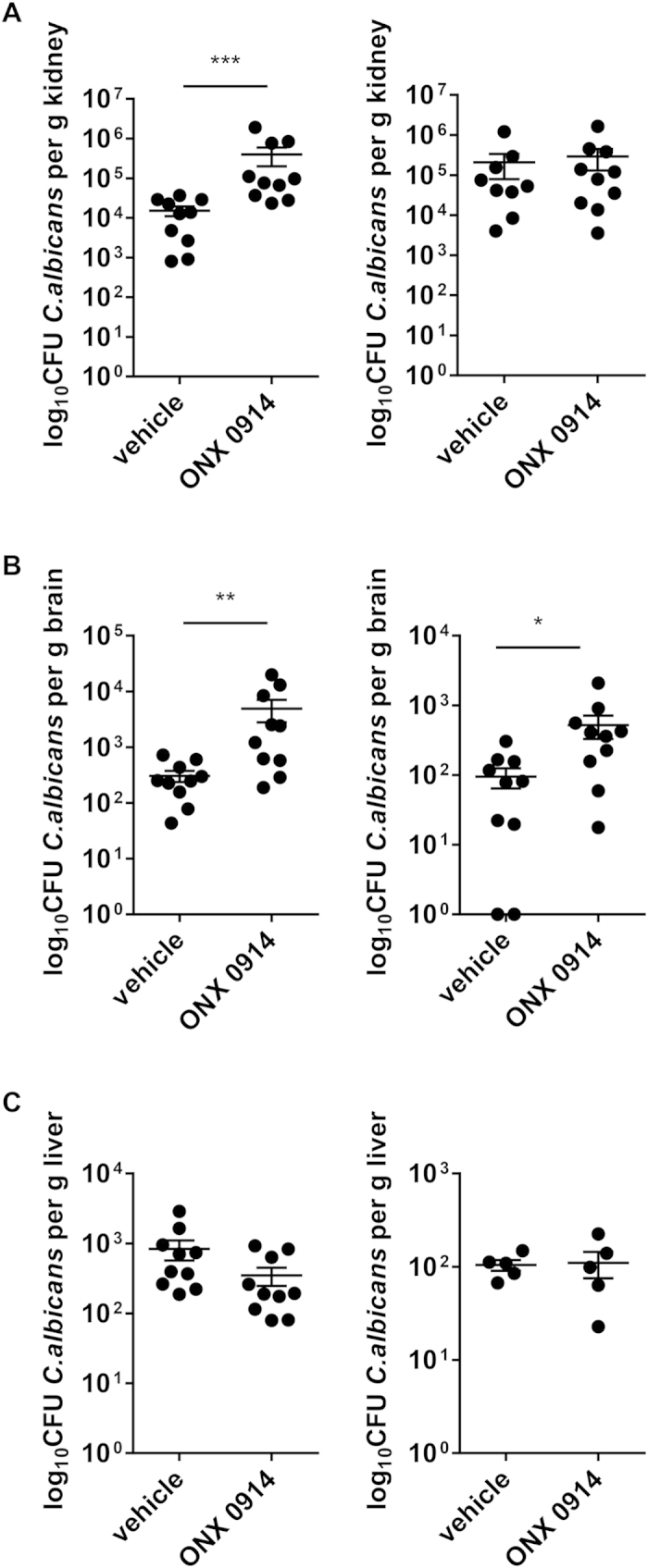

Mice with disseminated candidiasis die because of progressive sepsis and, notably, kidney fungal burden was shown to correlate with severity of renal failure and acidemia, which are hallmarks of severe sepsis28. Therefore, we investigated whether the observed enhanced susceptibility to systemic infection with C. albicans in ONX 0914 treated mice is due to defects in the control of the fungus. Kidney, brain, and liver tissue homogenates were analyzed for fungal outgrowth. Interestingly, mice treated with ONX 0914 had higher fungal burden in kidneys and brains compared to vehicle treated mice at early stages (day 3) of disseminated candidiasis (Fig. 4A,B). The increased fungal burden in the brain of ONX 0914 treated mice was also detectable at later stages (day 7) of infection (Fig. 4B). In contrast, in the liver (day 3 + 7) and at later time points in the kidney (day 7), LMP7 inhibition had no influence on the immune systems’ capability to control the fungus (Fig. 4A,C). Importantly, we found that ONX 0914 had no impact on the growth of C. albicans cultures in vitro (data not shown).

Figure 4. Influence of LMP7 inhibition on fungal burden in kidney, liver, and brain.

Mice were intravenously infected with 1 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) every second day. On day 3 (left panels) and day 7 (right panels) fungal burden was determined in kidneys (A), brains (B), and livers (C). Bars show mean log10 CFU/g tissue +/− SEM. Data represent pooled results from two independent experiments and are analyzed by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Antifungal treatment is still effective in ONX 0914 treated mice

We wondered whether the increased susceptibility to systemic candidiasis observed upon LMP7 inhibition would be treatable with antifungal agents like Amphotericin B (AmpB). Mice receiving vehicle or ONX 0914 were daily treated with 10 mg/kg AmpB. Strikingly, these mice, no matter if treated with vehicle or ONX 0914, were almost fully protected from weight loss (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Analyzing renal fungal burden revealed that independent of LMP7 inhibition, AmpB treatment resulted in almost complete clearance of the fungus on day 7 postinfection (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

Elevated neutrophil numbers in kidneys and brains of ONX 0914 treated mice during invasive candidiasis

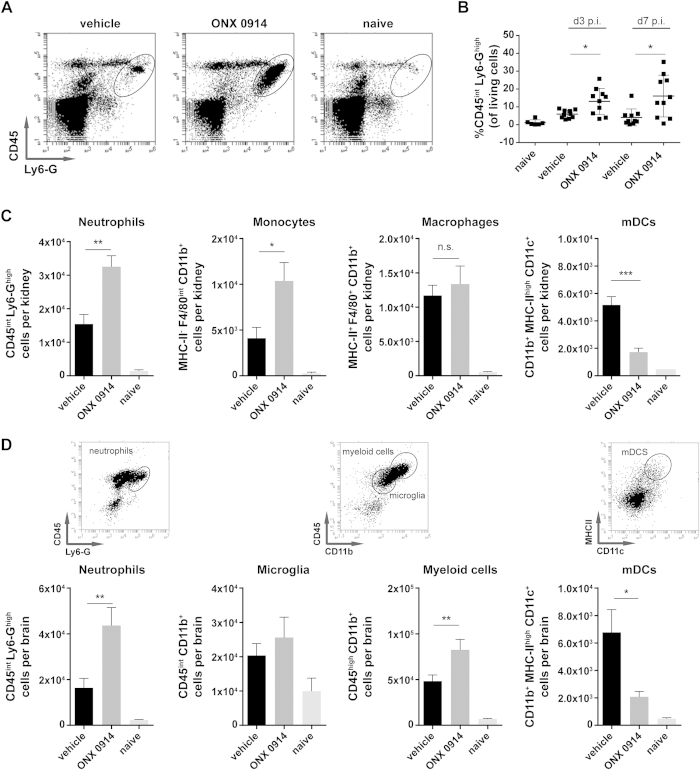

Defects in IL-17 immunity are often associated with impaired neutrophil recruitment and function22,32. Hence, we investigated the influence of ONX 0914 treatment on neutrophil recruitment to the kidney, which is the main target of systemic candidiasis26,27,28,33. Unexpectedly, we observed significantly increased CD45int Ly6-Ghigh neutrophil numbers in the kidneys of ONX 0914 treated mice both early (day 2 + 3) and late (day 7) in the course of invasive candidiasis (Fig. 5A–C) as detected by flow cytometric analysis of purified renal leukocytes. Moreover, we observed significantly increased numbers of kidney infiltrating F4/80+ CD11b+ MHC-II- monocytes upon LMP7 inhibition 48 h postinfection (Fig. 5C). While the infiltration of F4/80+ CD11b+ MHC-II+ macrophages was not affected by LMP7 inhibition, we found reduced numbers of CD11b+ MHC-IIhigh CD11c+ myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) in the kidney of ONX 0914 treated mice (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, we noticed a strong inflammatory infiltration of innate immune cells into the brain on day 3 of systemic infection with C. albicans in both, ONX 0914 and vehicle treated mice (Fig. 5D). Nevertheless, compared to vehicle treated mice, ONX 0914 treatment resulted in a strong increase of CD45int Ly6-Ghigh neutrophils and CD45high CD11b+ myeloid cells while infiltrating CD11b+ MHC-IIhigh CD11c+ mDCs numbers were reduced (Fig. 5D). CNS resident CD45int CD11b+ microglia, which were demonstrated to be the main cell type responding to C. albicans in the brain33, were also increased upon infection. However, we observed no difference between vehicle and ONX 0914 treated mice.

Figure 5. Elevated neutrophil numbers in the kidney and the brain of ONX 0914 treated mice.

Mice were i.v. infected with 1.5 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) every second day. Kidneys and brains were removed and isolated leukocytes were stained for Ly6-G, CD45, F4/80, CD11b, MHC-II, and CD11c and analyzed by flow cytometry (gated on living cells according to FSC/SSC). Graphs show (A) representative flow cytometry profiles of kidney infiltrating CD45intLy6-Ghigh neutrophils on day 7, (B) pooled results from two independent experiments presented as mean percentage of kidney infiltrating CD45intLy6-Ghigh neutrophils +/− SEM, (C,D) pooled results from two independent experiments presented as mean absolute numbers +/− SEM of (C) kidney infiltrating CD45intLy6-Ghigh neutrophils, MHCII-F4/80intCD11b+ monocytes, MHCII+ F4/80+ CD11b+ macrophages, and CD11b+MHCIIhighCD11c+ myeloid derived dendritic cells (mDCs) 48 h p.i., and (D) brain infiltrating CD45intLy6-Ghigh neutrophils, CD45highCD11b+ myeloid cells, CD11b+MHCIIhighCD11c+ mDCs, and CD45intCD11b+ CNS resident microglia 72 h p.i. Data were analyzed by students t test with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

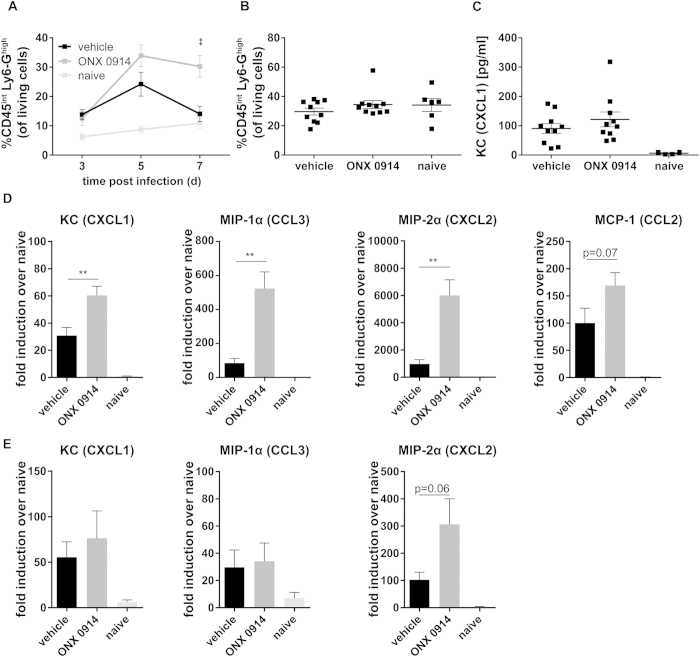

In an attempt to identify the cellular source of the increase of neutrophilic granulocytes, we detected significantly elevated numbers of blood neutrophils in mice treated with ONX 0914, particularly at later stages of infection (Fig. 6A). However, when analyzing bone marrow neutrophils we could not find any difference in the percentage of mature CD45int Ly6-Ghigh cells between vehicle and ONX 0914 treated mice on day 3 (Fig. 6B) or day 5 postinfection (data not shown) suggesting that the development of neutrophils in the bone marrow was not affected. In order to clarify the reason for the increased neutrophil numbers in blood and kidney upon LMP7 inhibition, we assessed the expression of important chemoattractants for monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. On day 3 postinfection, we detected increased keratinocyte-derived cytokine (KC) (CXCL1) serum cytokine levels (Fig. 6C) which were not altered by ONX 0914 treatment. In contrast, kidney mRNA levels of KC (CXCL1), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α (CCL3), monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 (CCL2), and MIP-2α (CXCL2) were strongly upregulated upon LMP7 inhibition 48 h postinfection (Fig. 6D). At later stages (day 7) of systemic candidiasis, no difference was seen for KC and MIP-1α (CCL3), whereas MIP-2α (CXCL2) was still upregulated (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Influence of ONX 0914 treatment on neutrophil recruitment.

Mice were i.v. infected with 1 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) every second day. (A) Peripheral blood (day 3, 5, and 7) and (B) bone marrow cells were stained for Ly6-G and CD45 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Graphs show mean percentage of CD45intLy6-Ghigh neutrophils (gated on living cells according to FSC/SSC) +/− SEM. (C) Serum levels of KC (CXCL1) were determined by cytometric bead array. Graphs show pooled data from two independent experiments and are presented as mean +/− SEM. (D,E) Relative mRNA expression of KC (CXCL1), MIP-1α (CCL3), MCP-1 (CCL2), or MIP-2α (CCXL2) in the kidney on day 2 (D) or day 7 p.i. (E). Real-time RT-PCR data are pooled from two independent experiments with n = 8–10 mice per group and expressed as fold induction over naive +/− SEM relative to one out of four naive mice, which served as uninfected control. Data were analyzed by students t test with **p < 0.01.

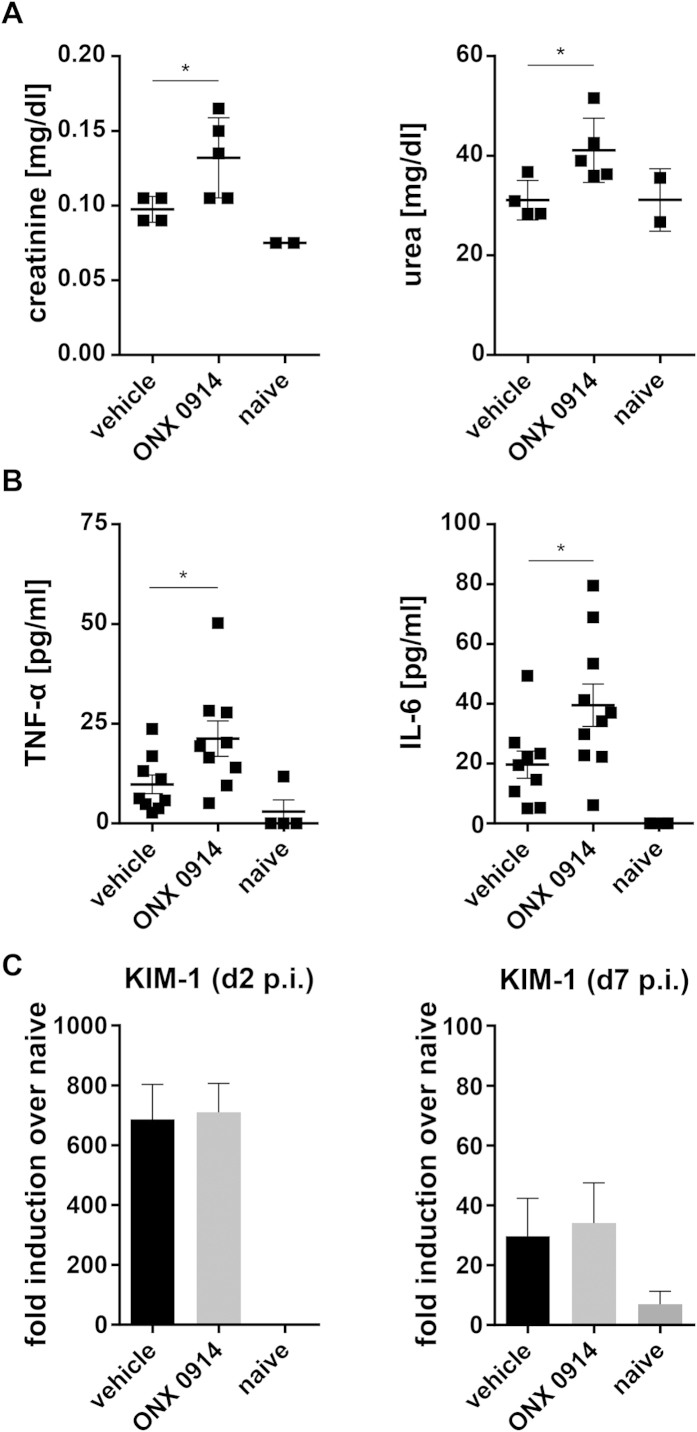

Enhanced neutrophil recruitment to the kidney during systemic candidiasis has been correlated with inflammation and immunopathology-mediated renal failure31. This would fit to the observation that ONX 0914 treated mice are more susceptible to invasive candidiasis and indicate that these mice might suffer from deregulated immunopathology leading to increased renal tissue damage. Indeed, in some cases, the kidneys of ONX 0914 treated mice appeared paler and more swollen than kidneys of vehicle treated mice by gross pathology (data not shown). In ONX 0914 treated mice we found elevated serum levels of creatinine and urea on day 7 (Fig. 7A) and of TNF-α and IL-6 on day 3 and day 7 (Fig. 7B; data not shown) indicating that renal failure and sepsis might occur faster upon LMP7 inhibition. Renal mRNA expression of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), a marker for early kidney damage, was strongly upregulated on day 2 and day 7 postinfection, but no difference could be detected between ONX 0914 and vehicle treated mice (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. Influence of LMP7 inhibition on the maintenance of kidney function and proinflammatory serum cytokine levels.

Mice were i.v. infected with 1 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) every second day. Graphs show (A) photometrically determined serum levels of urea and creatinine on day 7 and (B) serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α as detected by cytometric bead array on day 3. (C) Relative mRNA expression of KIM-1 on day 2 and day 7, pooled from two independent experiments with n = 8–10 mice per group, and presented as fold induction over naive +/− SEM relative to one out of four naive mice, which served as uninfected control. Data are analyzed by students t test with *p < 0.05.

Reduced activation of innate immune cells upon LMP7 inhibition in vivo

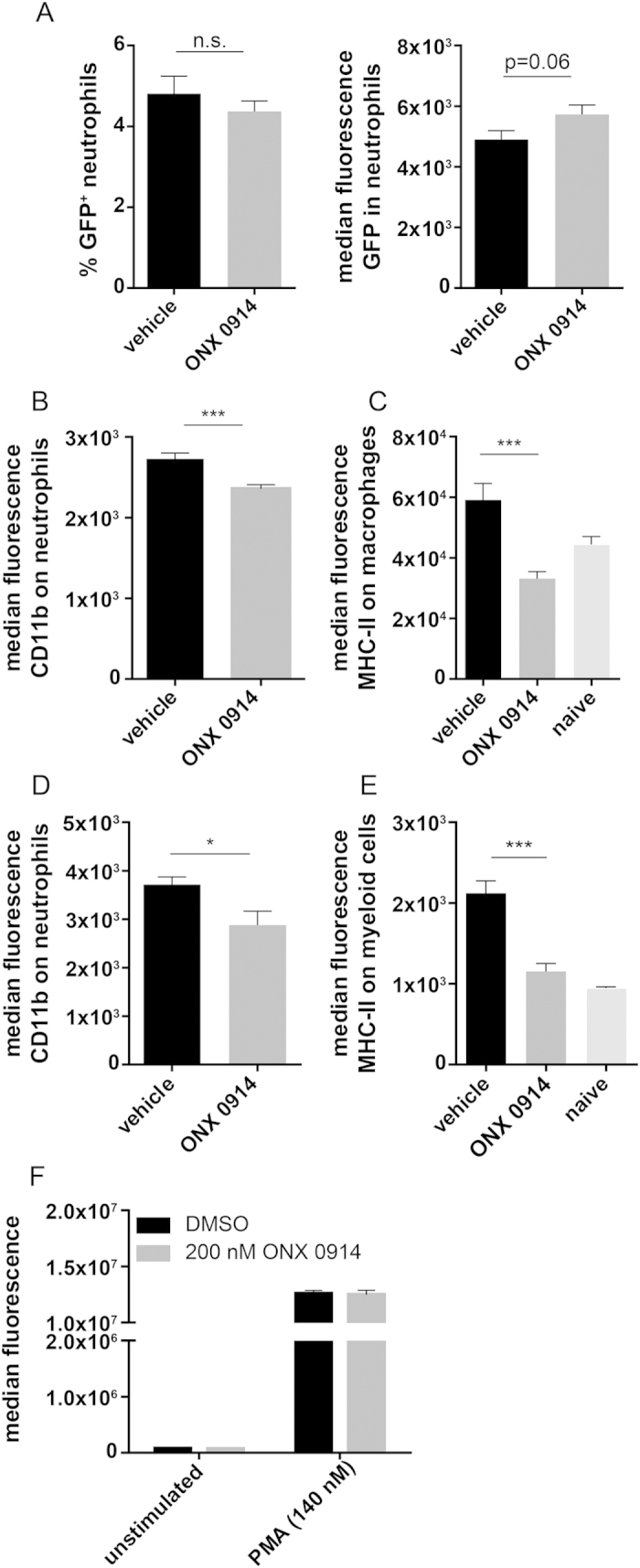

Increased renal fungal burden during systemic C. albicans infection suggests impaired fungal control by innate immune cells. Especially neutrophils represent key innate immune effector cells that play a crucial role in phagocytosis and killing of C. albicans34. To assess the ability of neutrophils to kill C. albicans, mice were infected with a strain of GFP-positive C. albicans and the GFP signal among kidney neutrophils was measured. We found no difference in the percentage of GFP+ neutrophils between ONX 0914 treated and control mice (Fig. 8A) indicating that the phagocytic activity of neutrophils is not affected by LMP7 inhibition. However, there was a slightly (not quite significantly) higher median fluorescence of GFP within neutrophils of ONX 0914 treated mice which suggests that killing efficiency of neutrophils might be reduced by LMP7 inhibition (Fig. 8A). Moreover, we observed that neutrophils of ONX 0914 treated mice in the kidney as well as in the brain expressed reduced levels of the activation marker CD11b (Fig. 8B,D). Additionally, infiltrating macrophages in the kidney and myeloid cells of the brain expressed significantly lower levels of MHC class II supporting the hypothesis that LMP7 inhibition interferes with proper activation of innate immune cells in response to C. albicans (Fig. 8C,E). However, ONX 0914 treatment did not alter the capacity of isolated human neutrophils to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vitro (Fig. 8F).

Figure 8. Influence of LMP7 inhibition on C. albicans-induced activation of innate immune cells.

(A) Mice were intravenously infected with 1.5 × 105 CFU live C. albicans-GFP blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) on the day of infection. 48 h p.i., kidneys were removed and isolated leukocytes were stained for Ly6-G and CD45. Graph shows mean percentages of GFP+CD45intLy6-Ghigh cells or median fluorescence of GFP in CD45intLy6-Ghigh cells +/− SEM, respectively. (B–E) Mice were i.v. infected with 1.5 × 105 CFU live C. albicans blastoconidia and treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg ONX 0914 (s.c.) on the day of infection. Graphs show median fluorescence +/− SEM of CD11b expression on (B) kidney or (D) brain infiltrating CD45intLy6-Ghigh neutrophils and MHC class II expression on (C) kidney infiltrating MHC-II+F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages or (E) brain infiltrating CD45high CD11b+ myeloid cells, respectively. Data were pooled from two independent experiments (n = 7–10 mice per group). Data were analyzed by students t test with *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001. (F) NADPH oxidase activity as determined by DHR test. Isolated human neutrophils were treated with DMSO or 200 nM ONX 0914 in vitro for one hour and stimulated with 140 nM PMA for 30 min. Graph shows result from one experiment representative for three different blood donors.

Discussion

Besides its important role in MHC class I antigen processing, the immunoproteasome was found to be involved in proinflammatory immune responses and T helper cell differentiation9,11 while immunoproteasome inhibition ameliorated the outcome of several autoimmune diseases9,10,11,12,13,14. However, T helper cells do not only exert pathogenic functions in autoimmune disorders but also play a central role in host defence against for example fungal infections. In this study, we have investigated whether LMP7 inhibition would also affect T helper cell differentiation in response to C. albicans, a strong inducer of Th1 and Th17 cells17,18,19. Indeed, we found a reduced production of the Th1- and Th17-derived cytokines IL-17A and IFN-γ by ONX 0914 treated human PBMCs and murine splenocytes in vitro stimulated with heat-killed C. albicans (Fig. 1A,B). IL-17A and IFN-γ might also be produced by other cell types present in bulk splenocytes or PBMCs, however, treatment of CD4+ T cells was sufficient to reduce their release into the supernatant although not quite significantly for IFN-γ (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Moreover, IL-17A production was strongly dependent on MHC-II antigen presentation, indicating that LMP7 inhibits release of IL-17A by T helper cells (Supplementary Fig. S2C). IFN-γ and IL-17A production was also strongly reduced when only the ‘antigen presenting cells’-containing fraction (splenocytes - CD4+ T cells) was treated with ONX 0914 (Supplementary Fig. S2A), suggesting that immunoproteasome inhibition affects T helper cells as well as antigen presenting innate immune cells. Corroboratively, LMP7 inhibition in vivo led to a reduced generation of IL-17A- and IFN-γ- producing cells in mice systemically infected with C. albicans (Fig. 2) supporting the idea that LMP7 inhibition interferes with the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells.

ONX 0914 treated mice displayed a higher susceptibility to systemic candidiasis compared to vehicle treated control mice which, unexpectedly, manifested at very early stages of infection. We observed a more pronounced weight loss, an impaired survival, and a higher fungal burden of the kidney and the brain (Figs 3B,C and 4A,B). Interestingly, mice lacking immunoproteasome subunits LMP2, MECL-1, or LMP7 showed no difference in weight loss (Fig. 3A) or survival (data not shown) compared to WT mice. The difference between LMP7−/− and ONX 0914 treated mice might be explained by structural changes in the immunoproteasome when LMP7 is absent and replaced by its constitutive counterpart β5 which maintains the chymotrypsin-like activity in immunoproteasomes of LMP7−/− cells35. In contrast, when LMP7 is chemically inhibited with ONX 0914, the LMP7-dependent chymotrypsin-like activity of the immunoproteasome is irreversibly blocked. However, the influence of LMP7 inhibition became apparent far too early for impaired T helper cell differentiation being the reason for the increased susceptibility of ONX 0914 treated mice. In fact, adaptive immunity does not play a prominent role in combatting disseminated candidiasis. Instead, resistance to systemic C. albicans infection is mainly mediated by innate immune cells indicating that immunoproteasome inhibition has a more versatile effect on the anti-C. albicans immunity25,30,36.

Neutrophils are key innate immune effector cells that play a crucial role in phagocytosis and killing of C. albicans20,34,37. Therefore, it was surprising to observe strongly increased neutrophil numbers (Fig. 5) and higher fungal burden in the brains and kidneys of ONX 0914 treated mice (Fig. 4A,B) at the same time. Excessive neutrophil accumulation is most probably a compensatory event to fight increased renal fungal burden which might in turn result from impaired candidacidal activity of neutrophils and/or other innate immune cells as observed by others38. Upon PMA stimulation of purified PMNs in vitro, we observed no effect of LMP7 inhibition on the production of ROS (Fig. 8F), representing an important killing mechanism of neutrophils. However, killing of C. albicans by neutrophils occurs intracellularly and extracellularly as well as through oxidative and non-oxidative mechanisms. Hence, LMP7 might affect one or several non-oxidative killing mechanisms like for example the ability of neutrophils to phagocytose C. albicans or to form extracellular traps by releasing decondensed chromatin fibres decorated with antifungal proteins15,39. Moreover, LMP7 inhibition might influence neutrophil activity in an indirect manner. In fact, DCs which are strongly reduced in the brains and kidneys of ONX 0914 treated mice (Fig. 5C,D), were shown to be essential to sustain the anti-microbial activity of neutrophils via the induction of natural killer (NK) cells to produce GM-CSF38. Correspondingly, brain and kidney neutrophils of ONX 0914 treated mice displayed reduced expression of the activation marker CD11b which is part of the complement receptor CR3 and important for phagocytosis of C. albicans (Fig. 8B,D). Recently, Whitney et al. used GFP+ C. albicans to assess killing capacity of neutrophils in vivo. They observed a greater frequency of GFP+ neutrophils in CD11cΔSyk mice than in controls and concluded that kidney neutrophils from the former strain are impaired in their ability to destroy the fungus38. We found no difference in the percentage of GFP+ C. albicans containing neutrophils (Fig. 8A). However, this could mean that either uptake and killing is not affected by LMP7 inhibition or that neutrophils of ONX 0914 treated mice have reduced phagocytic activity. However, we noticed slightly enhanced fluorescence of GFP (reflecting the number of viable GFP+ C. albicans) within GFP+ neutrophils which might suggest reduced killing capacity in vivo. Additionally, we detected strongly decreased MHC class II expression on the surface of myeloid cells in the brain and macrophages in the kidney of ONX 0914 treated mice (Fig. 8C,E) suggesting that LMP7 inhibition interferes with a proper activation of innate immune cells and, consequently, probably also with an effective fungal control by these cells.

In order to characterize the influence of LMP7 inhibition on neutrophils in systemic candidiasis, we wanted to investigate whether increased neutrophil numbers result from an enhanced recruitment from peripheral blood. Interestingly, we observed elevated blood neutrophils in ONX 0914 treated mice particularly at later stages of disease (Fig. 6A). We found no difference in the percentage of neutrophils in the bone marrow between ONX 0914 treated and vehicle treated mice (Fig. 6B) suggesting that LMP7 inhibition has no impact on granulopoiesis but only leads to increased neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection or, possibly, to reduced neutrophil clearance in the periphery.

Interestingly, ONX 0914 treatment did only result in increased fungal burden in the kidney and the brain but not in the liver (Fig. 4). Hence, the question arises why control of C. albicans growth is only affected in the brain and in the kidney which are, also under “normal” circumstances, the most affected organs during systemic candidiasis37. Failure of fungal clearance might relate to organ-specific factors that impair neutrophil function, such as the high osmolarity and urea content of renal tubules, or, for example, to the induction of regulatory responses33,40. Indeed, hyphal forms of C. albicans, which are only found in the kidney (but not in the spleen or in the liver), are more resistant to killing by phagocytes than yeasts and too large to be ingested by neutrophils, which instead degranulate and release oxidative contents extracellularly thereby contributing to tissue damage33. Furthermore, hyphae induce a more anti-inflammatory profile than the yeast form, suggesting that morphogenetic changes can modulate the immune response to the advantage of the fungus. Conveniently, the PRR genes most highly upregulated in response to infection in the kidney were TLR2 and dectin-2, which is involved in the recognition of C. albicans hyphae37. Although TLR2 signaling can induce the production of proinflammatory mediators such as MIP-2, KC, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ37,41, it can also induce IL-10 production and the expansion of Treg cells, suppressing immune responses to C. albicans42,43,44. Likewise, the anti-inflammatory milieu within the immune-privileged CNS might also contribute to reduced anti-C. albicans immunity within the brain45,46,47,48,49. Interfering with proinflammatory immune responses by LMP7 inhibition might further enhance the advantageous environment for fungal growth within these organs.

It has been demonstrated that disease severity in C. albicans infections correlates with kidney levels of many cytokines and chemokines like IL-6, KC (CXCL1), MIP-2 (CXCL2), TNF, and MCP-1 (CCL2)30. Interestingly, these cytokines and chemokines were strongly upregulated in ONX 0914 treated mice (Figs 6D,E and 7B). In particular, MacCallum et al. demonstrated significant correlation of early kidney KC (CXCL1) concentrations with subsequent histological kidney lesion parameters30. Hence, the development of tissue pathology in C. albicans-infected mice appears to depend on relative balances of cytokine or chemokine production and of neutrophil recruitment to the kidney supporting a direct exacerbating effect of LMP7 inhibition on the pathogenesis of disseminated candidiasis. Although neutrophils represent a central arm of the anti-C. albicans immunity they may also be harmful to the host by mediating immunopathology and tissue injury31. While sepsis is the major cause of death in systemic candidiasis, the extent of kidney damage in animals showing severe symptoms contributes to the overall pathology of the disease28,30. It has been recognized for many years that the disease processes in C. albicans-infected kidneys lead to heavy host leukocyte infiltrates and microabscess formation which in turn result in tissue damage30. Hence, excessive infiltration of monocytes and neutrophils into the brain and the kidney of ONX 0914 treated mice (Fig. 5C,D) might lead to meningoencephalitis and kidney injury, respectively29,31,33,50. Indeed, at least in some experiments, we noticed that kidneys of ONX 0914 treated mice had severe swelling and pallor in gross pathology and that these mice display altered behaviour as manifested by movement disorders and neurological abnormalities (data not shown). Moreover, although the expression of KIM-1, a marker of tubular epithelial damage currently used for diagnosis of acute kidney injury in humans51, was not changed (Fig. 7C), we measured significantly elevated TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 7B) as well as urea and creatinine (Fig. 7A) levels in the serum of ONX 0914 treated mice. This suggests that LMP7 inhibition contributes to both death-associated pathologies, sepsis as well as renal failure, respectively.

Taken together, it appears that LMP7 inhibition leads to reduced Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation in response to C. albicans but also affects the innate immunity resulting in higher susceptibility of ONX 0914 treated mice to systemic candidiasis. Hence, the question arises whether immunoproteasome inhibitors can in general be applied in the therapy of autoimmunity if they interfere with host defence against pathogens like fungi. Proteasome inhibitors are already used in humans e.g. for the treatment of multiple myeloma and, importantly, except for an increased incidence of varicella herpes zoster in bortezomib treated patients, there is no evidence for higher susceptibility to fungal infections52,53. Moreover, during infection with WT vaccinia virus (VV-WR) or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV-WE), we observed no influence on the immune system’s capability to clear the virus in mice treated with ONX 09149. Nevertheless, it would be worthwhile to investigate the influence of LMP7 inhibition for example on oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) where host resistance is strictly dependent on T helper cells23. However, since even systemic candidiasis can be easily controlled with standard fungicide therapy (Supplementary Fig. S3), our data do not discourage the development and testing of LMP7-selective inhibitors as therapeutics against autoimmune diseases and inflammatory disorders.

To our knowledge this is the first time that ONX 0914 treatment was demonstrated to affect the innate immunity. An underlying mechanism could be reduced IL-23 secretion by dendritic cells and tissue-resident macrophages as observed for human PBMCs9,13. This would, for example, affect IL-23R+ IL-17-producing immune cells like γδT cells, iNKT cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), or nTH17 cells which are implicated in host defence against C. albicans54,55,56. Moreover, Whitney et al. recently demonstrated that IL-23 produced by DCs is essential to induce GM-CSF production in NK cells which in turn sustains anti-microbial activity of neutrophils, the main fungicidal effectors38,57. Hence, it is of great interest to further investigate the role of the immunoproteasome in innate immunity and to determine the underlying mechanism of its influence on host defence against C. albicans and other pathogens.

Material and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) were originally purchased from Charles River, Germany. MECL-158, LMP259, and LMP7 gene-targeted mice60 were provided by John Monaco (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH). Mice were kept in a specific pathogen-free facility and used at 8–10 weeks of age. Animal experiments were approved by the Review Board of Governmental Presidium Freiburg of the State of Baden-Württemberg. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Immunoproteasome inhibition

For in vitro experiments, the LMP7-selective inhibitor ONX 0914 (Onyx Pharmaceuticals) was dissolved at a concentration of 10 mM in DMSO and stored at −80 °C. For in vivo proteasome inhibition, ONX 0914 was formulated in an aqueous solution of 10% (w/v) sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin and 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6) referred to as vehicle and administered to mice as an s.c. bolus dose of 10 mg/kg.

Systemic infection with C. albicans

The Candida albicans laboratory strain SC5314 (kind gift from Prof. Joachim Morschhäuser, Institute for Molecular Infection Biology, University of Würzburg) or C. albicans strain CAI4-pACT1 GFP (kind gift from Prof. Salome LeibundGut, Institute of Microbiology, ETH Zürich) was grown on YPD plates at 30 °C. A single colony of C. albicans was grown for 18 h at 30 °C in YPD media and yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with PBS, and counted with a hemocytometer. Mice were injected i.v. with blastoconidia in PBS and their health status was monitored daily. Animals that became immobile or otherwise showed signs of severe illness were humanely terminated and recorded with 30% weight loss and as dying on the following day. For in vitro experiments, C. albicans yeast and hyphae were heat-killed for 1 h at 100 °C. To generate pseudohyphae, blastoconidia were grown at 37 °C and 6% CO2 in serum-free RPMI medium overnight.

Fungal burden

To assess the tissue outgrowth of C. albicans, kidneys, brains, and livers of the sacrificed animals were removed aseptically, weighed, and homogenized in sterile distilled water using a tissue homogenizer. The number of viable C. albicans cells in the tissues was determined by plating serial dilutions on YPD plates. The colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation at 30 °C, and the fungal burden was expressed as log10 CFU/g tissue.

Antifungal therapy

Amphotericin B was purchased as FungizoneTM (Medicopharm AG, Germany). Amphotericin B as raw material (50 mg) was dispersed in 10 ml sterile distilled water and aliquots were stored at −20 °C. Amphotericin B stock solution (5 mg/ml) was diluted with 5% glucose (pH > 4.2) and administered intraperitoneally as a single bolus of 10 mg/kg every day.

Ex vivo cytokine production by primed splenocytes

To assess in vivo T helper cell differentiation, ~5 × 106 primed spleen cells from C. albicans infected mice were in vitro restimulated with heat-killed C. albicans yeast (~106 cells/mL) and cultured for 48 h at 37 °C. Culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-17A and IFN-γ by ELISA according to the manufacturer´s protocol (eBioscience).

In vitro T helper cell differentiation

Human PBMCs from healthy volunteers (2.5 × 105/well) or bulk splenocytes of naive C57BL/6 (2 × 105/well) were pulsed for 2 h with 200 nM ONX 0914 at 37 °C, washed and cultured in the presence of heat-killed C. albicans yeast or hyphae (~1 × 106 cells/ml) in IMDM at 37 °C. Cytokines in the supernatant were determined by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (eBioscience). In some experiments (Supplementary Fig. S2A, 2B), splenocytes were magnetically sorted (MACS) for CD4+ T cells using a negative sorting approach. Either CD4+ T cells or the ‘antigen presenting cell’-containing cell fraction (splenocytes - CD4+ T cells) were pulsed with ONX 0914 before combining both fractions and stimulating with C. albicans.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was used to quantify cytokine expression levels in mouse kidney as previously described13 with slight modifications. RNA from mouse kidney was extracted with the RNeasy mini plus kit of Qiagen. One μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using oligonucleotide (dT) primers (see Table 1) and the reverse transcription system (Promega). Gene expression was normalized to glycerolaldehyd-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a reference gene and results for all mice are expressed relative to one naive uninfected mouse (fold induction over naive).

Table 1. PCR primers used in this study.

| Target gene | Fwd Primer | Rev primer |

|---|---|---|

| MIP-2α | 5′ -AAGTTTGCCTTGACCCTGAA-3′ | 5′ -AGGCACATCAGGTACGATCC-3′ |

| KC | 5′ -TGGCTGGGATTCACCTCAAG-3′ | 5′ -CCGTTACTTGGGGACACCTT-3′ |

| MIP-1α | 5′ -GTAGCCACATCGAGGGACTC-3′ | 5′ -GATGGGGGTTGAGGAACGTG-3′ |

| MCP-1 | 5′ -TCAGCCAGATGCAGTTAACG-3′ | 5′ -GTTGTAGGTTCTGATCTCATTTGG-3′ |

| KIM-1 | 5′ -ACATTCTCCGTAAATGGGCTT-3′ | 5′ -CTGCTGTGAAGGAGACCCTG-3′ |

Isolation of leukocytes from kidney

Mice were sacrificed and leukocytes from the kidney were isolated by enzymatic digestion of tissues with collagenase D (0.2 mg/ml) and DNase I (0.2 mg/ml) followed by Percoll® density gradient (70%/30%) centrifugation. Cells were collected from the interphase and analyzed for surface marker expression by flow cytometry.

Isolation of leukocytes from brain

Mice were sacrificed and perfused with cold PBS to minimize contamination of brain and spinal cord with blood-derived leukocytes from peripheral blood. Leukocytes from CNS were isolated by enzymatic digestion of brains followed by Percoll® density gradient centrifugation as previously described13.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described13. Abs to Ly6-G (RB6-8C5), CD45 (30-F11), IL-17A (eBio17B7), F4/80 (BM8), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (HL3), MHC-II (AF6-120.1), were obtained from BD Biosciences or eBioscience. Anti-IFN-γ antibody (AN18) was kindly provided by Dr. Michael Basler. Cells were acquired with the use of the BD AccuriTM C6 flow cytometer system and pregated on living cells according to FSC/SSC signal.

Bead-based cytokine assay

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and KC (CXCL1) were determined by multiplexed bead-based assays (Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine Assays, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were analyzed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems, Heidelberg, Germany). Absolute cytokine concentrations were calculated based on the mean fluorescence intensity of cytokine standards with a 4-parameter logistic curve model. The sensitivity of the assays was 1.4 pg/ml for TNF-α, 0.2 pg/ml IL-6, and 0.3 pg/ml for KC.

Photometric assays

Serum creatinine and urea were measured photometrically using an automated clinical chemistry analyser (ADVIA 1800, Siemens) at the medical laboratory Dr. Brunner in Konstanz.

Isolation of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) from human peripheral blood

Neutrophils were isolated using a density gradient centrifugation method. In brief, 1 part of 1× HBSS diluted blood (without Ca2+/Mg2+) was carefully underlayed by Ficoll PaqueTM Plus (δ = 1.077 g/ml) and centrifuged at 400 × g, 20 °C for 40 min without brake. Supernatant and mononuclear cell fraction were removed and the pellet was washed in HBSS. Erythrocytes were lysed with H2O for 20 s and PMNs were washed and resuspended in HBSS.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from human blood

Human PBMCs were isolated from whole blood with the help of BD Vacutainer® CPTTM and cultured in RPMI medium.

NADPH oxidase activity assay

PMNs (5.0 × 106 cells/ml) that were previously treated with DMSO or 200 nM ONX 0914 for 1 h at 37 °C were activated or not with 140 nM PMA for 30 min at 37 °C, respectively. After stimulation, the cells were incubated with 50 μM DHR for 30 min, washed once, and resuspended in HBSS. The fluorescence of gated neutrophils was detected in FL1 using the BD AccuriTM C6 flow cytometer.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance was determined using the students t test, two-way ANOVA or non-parametric Mann-Whitney test with two-tailed P value. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software (version 4.03) (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was achieved when p < 0.05. If not indicated otherwise, differences are not significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mundt, S. et al. Inhibiting the immunoproteasome exacerbates the pathogenesis of systemic Candida albicans infection in mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 19434; doi: 10.1038/srep19434 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Joachim Morschhäuser and Prof. Salomé LeibundGut-Landmann for the contribution of C. albicans, Christopher J. Kirk for the gift of ONX 0914, and Magdalene Vogelsang for excellent technical assistance. This work was funded by German Research Foundation grants Nr. BA 4199/2-1 and GR 1517/14-1 and the Swiss National Science Foundation grant Nr. 31003A_138451

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.M. designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. H.E. performed the bead-based cytokine assays. M.B. designed the experiments, supervised the project and corrected and refined the manuscript. S.B. helped with fluorescent activated cell sorting experiments and corrected and refined the manuscript. M.G. supervised the project and corrected and refined the manuscript.

References

- Goldberg A. L. & Rock K. L. Proteolysis, proteasomes and antigen presentation. Nature 357, 375–379 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coux O., Tanaka K. & Goldberg A. L. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 801–847 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock K. L. et al. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell 78, 761–771 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groettrup M., Khan S., Schwarz K. & Schmidtke G. Interferon-gamma inducible exchanges of 20S proteasome active site subunits: why? Biochimie 83, 367–372 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. F., Cruz M., Rangwala R., Deepe G. S. & Monaco J. J. Regulation of immunoproteasome subunit expression in vivo following pathogenic fungal infection. J. Immunol. 169, 3046–3052 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber E. M. et al. Immuno- and constitutive proteasome crystal structures reveal differences in substrate and inhibitor specificity. Cell 148, 727–738 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M., Kirk C. J. & Groettrup M. The immunoproteasome in antigen processing and other immunological functions. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 25, 74–80 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groettrup M., Kirk C. J. & Basler M. Proteasomes in immune cells: more than peptide producers? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 73–78 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchamuel T. et al. A selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome subunit LMP7 blocks cytokine production and attenuates progression of experimental arthritis. Nat. Med . 15, 781–787 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M., Dajee M., Moll C., Groettrup M. & Kirk C. J. Prevention of experimental colitis by a selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome. J. Immunol. 185, 634–641 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalim K. W., Basler M., Kirk C. J. & Groettrup M. Immunoproteasome subunit LMP7 deficiency and inhibition suppresses Th1 and Th17 but enhances regulatory T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 189, 4182–4193 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H. T. et al. Beneficial effect of novel proteasome inhibitors in murine lupus via dual inhibition of type I interferon and autoantibody-secreting cells. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 493–503 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M. et al. Inhibition of the immunoproteasome ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 226–238 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M., Mundt S., Bitzer A., Schmidt C. & Groettrup M. The immunoproteasome: a novel drug target for autoimmune diseases. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 33, 74–79 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeibundGut-Landmann S., Wuthrich M. & Hohl T. M. Immunity to fungi. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 449–458 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionakis M. S. & Netea M. G. Candida and host determinants of susceptibility to invasive candidiasis. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003079 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Veerdonk F. L. et al. The inflammasome drives protective Th1 and Th17 cellular responses in disseminated candidiasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2260–2268 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeibundGut-Landmann S. et al. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 8, 630–638 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo S. et al. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity 32, 681–691 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani L. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 275–288 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozalbo D., Maneu V. & Gil M. L. Role of IFN-gamma in immune responses to Candida albicans infections. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 19, 1279–1290 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Na L., Fidel P. L. & Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 624–631 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti H. R. et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 206, 299–311 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulurija A., Ashman R. B. & Papadimitriou J. M. Neutrophil depletion increases susceptibility to systemic and vaginal candidiasis in mice, and reveals differences between brain and kidney in mechanisms of host resistance. Microbiology 142 (Pt 12), 3487–3496 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt M. B., Aliprantis A., Hu B. & Glimcher L. H. Calcineurin regulates innate antifungal immunity in neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 207, 923–931 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisplinghoff H., Seifert H., Wenzel R. P. & Edmond M. B. Inflammatory response and clinical course of adult patients with nosocomial bloodstream infections caused by Candida spp. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12, 170–177 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg B. & Edwards J. E. The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Candida Sepsis. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep . 4, 387–399 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg B., Ibrahim A. S., Edwards J. E. Jr. & Filler S. G. Mice with disseminated candidiasis die of progressive sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 192, 336–343 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer O. et al. Type I interferons promote fatal immunopathology by regulating inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils during Candida infections. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002811 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum D. M., Castillo L., Brown A. J., Gow N. A. & Odds F. C. Early-expressed chemokines predict kidney immunopathology in experimental disseminated Candida albicans infections. PLoS One 4, e6420 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionakis M. S. et al. Chemokine receptor Ccr1 drives neutrophil-mediated kidney immunopathology and mortality in invasive candidiasis. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002865 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye P. et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J. Exp. Med. 194, 519–527 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionakis M. S., Lim J. K., Lee C. C. & Murphy P. M. Organ-specific innate immune responses in a mouse model of invasive candidiasis. J. Innate Immun. 3, 180–199 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuit K. E. Phagocytosis and intracellular killing of pathogenic yeasts by human monocytes and neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 24, 932–938 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohwasser R., Kuckelkorn U., Kraft R., Kostka S. & Kloetzel P. M. 20S proteasome from LMP7 knock out mice reveals altered proteolytic activities and cleavage site preferences. FEBS Lett. 383, 109–113 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo L. Y. et al. Inflammatory monocytes mediate early and organ-specific innate defense during systemic candidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 109–119 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum D. M. Massive induction of innate immune response to Candida albicans in the kidney in a murine intravenous challenge model. FEMS Yeast Res. 9, 1111–1122 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney P. G. et al. Syk signaling in dendritic cells orchestrates innate resistance to systemic fungal infection. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004276 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban C. F. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000639 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargan R. A., Hamilton-Miller J. M. & Brumfitt W. Effect of pH and osmolality on in vitro phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils in urine. Infect. Immun. 61, 8–12 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea M. G. et al. The role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 in the host defense against disseminated candidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 185, 1483–1489 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S. et al. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 916–928 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutmuller R. P. et al. Toll-like receptor 2 controls expansion and function of regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 485–494 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea M. G. et al. Toll-like receptor 2 suppresses immunity against Candida albicans through induction of IL-10 and regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 172, 3712–3718 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus T. et al. Microglial expression of the B7 family member B7 homolog 1 confers strong immune inhibition: implications for immune responses and autoimmunity in the CNS. J. Neurosci. 25, 2537–2546 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwidzinski E. et al. Indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase is expressed in the CNS and down-regulates autoimmune inflammation. FASEB J . 19, 1347–1349 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic V. et al. Astrocyte-induced regulatory T cells mitigate CNS autoimmunity. Glia 47, 168–179 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flugel A. et al. Neuronal FasL induces cell death of encephalitogenic T lymphocytes. Brain Pathol 10, 353–364 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. D., Gold L. I. & Moses H. L. Evidence for transforming growth factor-beta expression in human leptomeningeal cells and transforming growth factor-beta-like activity in human cerebrospinal fluid. Lab. Invest. 67, 360–368 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarathna D. H. et al. MRI confirms loss of blood-brain barrier integrity in a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis. NMR Biomed. 26, 1125–1134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya V. S. et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 outperforms traditional biomarkers of kidney injury in preclinical biomarker qualification studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 478–485 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y., Qian J., Li Y., Meng H. & Jin J. The high incidence of varicella herpes zoster with the use of bortezomib in 10 patients. Am J Hematol 82, 403–404 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varettoni M. et al. Late onset of bortezomib-associated cutaneous reaction following herpes zoster. Ann. Hematol. 86, 301–302 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua D. J. et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature 421, 744–748 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti H. R. et al. Oral-resident natural Th17 cells and gammadelta T cells control opportunistic Candida albicans infections. J. Exp. Med. 211, 2075–2084 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladiator A., Wangler N., Trautwein-Weidner K. & LeibundGut-Landmann S. Cutting edge: IL-17-secreting innate lymphoid cells are essential for host defense against fungal infection. J. Immunol. 190, 521–525 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar E., Whitney P. G., Moor K., Reis e Sousa C. & LeibundGut-Landmann S. IL-17 regulates systemic fungal immunity by controlling the functional competence of NK cells. Immunity 40, 117–127 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M., Moebius J., Elenich L., Groettrup M. & Monaco J. J. An altered T cell repertoire in MECL-1-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 176, 6665–6672 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kaer L. et al. Altered peptidase and viral-specific T cell response in LMP2 mutant mice. Immunity 1, 533–541 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehling H. J. et al. MHC class I expression in mice lacking the proteasome subunit LMP-7. Science 265, 1234–1237 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.