Abstract

Loss of Tsc1/Tsc2 results in excess cell growth that eventually forms hamartoma in multiple organs. Our study using a mouse model with Tsc1 conditionally knockout in mammary epithelium showed that Tsc1 deficiency impaired mammary development. Phosphorylated S6 was up-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium, which could be reversed by rapamycin, suggesting that mTORC1 was hyperactivated in Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium. The mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin restored the development of Tsc1−/− mammary glands whereas suppressed the development of Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands, indicating that a modest activation of mTORC1 is critical for mammary development. Phosphorylated PDK1 and AKT, nuclear ERα, nuclear IRS-1, SGK3, and cell cycle regulators such as Cyclin D1, Cyclin E, CDK2, CDK4 and their target pRB were all apparently down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands, which could be reversed by rapamycin, suggesting that suppression of AKT by hyperactivation of mTORC1, inhibition on nuclear ERα signaling, and down-regulation of cell-cycle-driving proteins play important roles in the retarded mammary development induced by Tsc1 deletion. This study demonstrated for the first time the in vivo role of Tsc1 in pubertal mammary development of mice, and revealed that loss of Tsc1 does not necessarily lead to tissue hyperplasia.

The genes Tsc1 and Tsc2 got their names from a severe autosomal dominant disorder, called Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), resulting from mutations in one or two of these genes. TSC is characterized by formation of hamartomas in multiple organs and tissues, including derma, smooth muscle, kidney and nervous system1. Given the serious consequences of mutations in these genes, the functions of Tsc1 and Tsc2 have been well investigated. The protein hamartin, encoded by Tsc1, and the protein tuberin, encoded by Tsc2, form a functional heterodimer (TSC1/TSC2) with a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity, which regulates signaling pathways controlling cell size, cell cycle and cellular proliferation1,2. TSC1 and TSC2 bind to each other via their respective coiled-coil domains2. It is TSC2 that contains a C-terminal GAP domain3, while binding of TSC1 seems to protect TSC2 against ubiquitin-mediated degradation4,5. Studies have shown that inactivating mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2 give rise to indistinguishable phenotypes in Drosophila. Therefore silence of either of these two genes is equally efficient to inhibit TSC1/TSC2 complex activity1.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine-threonine kinase belonging to the phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase family, is a principal downstream target of TSC1/TSC2 complex6. mTOR plays its role in two kinds of protein complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)7 and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2)8. mTORC1, containing mTOR, regulatory protein of mTOR (Raptor), PRAS40 and mLST8, is directly activated by a small GTPase called Ras-homology enriched in brain (Rheb), whose activation is controlled by TSC1/TSC2 complex7,9. TSC1/TSC2 complex binds to GTP-bound Rheb and stimulates GTP hydrolysis, so as to inhibit the activity of Rheb and subsequently causes inactivation of mTORC110. Therefore loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 will lead to sustained activation of mTORC1. Activated mTORC1 positively regulates several growth-related cellular process such as transcription and protein translation, which contributes to cell growth and cellular proliferation11. Notably, there exist a negative feedback regulation between mTORC1 and AKT, another key protein promoting cell survival and proliferation. When mTORC1 is activated, S6K, one of the mTORC1 downstream target, will disrupt the interaction of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) with insulin receptors12, leading to a blockage in insulin signaling to AKT13,14, and consequently suppress the AKT activity. Such negative feedback regulation on AKT by mTORC1 surely plays a vital role in controlling proper cell growth and proliferation.

Tissue and organ development demands appropriate cell growth, proliferation and apoptosis, where mTORC1 signaling exert a critical role. However embryonic lethality caused by knockout of a vital gene such as Tsc1 hinder our full knowledge about the role of the gene in development. The mammary gland, unlike other organs, undergoes most of its development postnatally with the onset of puberty rather than in utero15. Here we used a Cre-LoxP conditional knockout strategy to build a mouse model with a specific Tsc1 deletion in mammary epithelium, which can be born and grow into adult ages and allow us to study the in vivo effects of Tsc1 deletion in mammary development. Interestingly, Tsc1 deficiency did not caused hyperplasia of mammary epithelium but evidently retarded the mammary gland branching by decreasing epithelial cell proliferation and increasing cell apoptosis. This study indicated that a modest mTORC1 activity was critical for pubertal mammary gland development in mice.

Results

Conditional knockout of Tsc1 in mammary epithelium impaired mammary development in mice

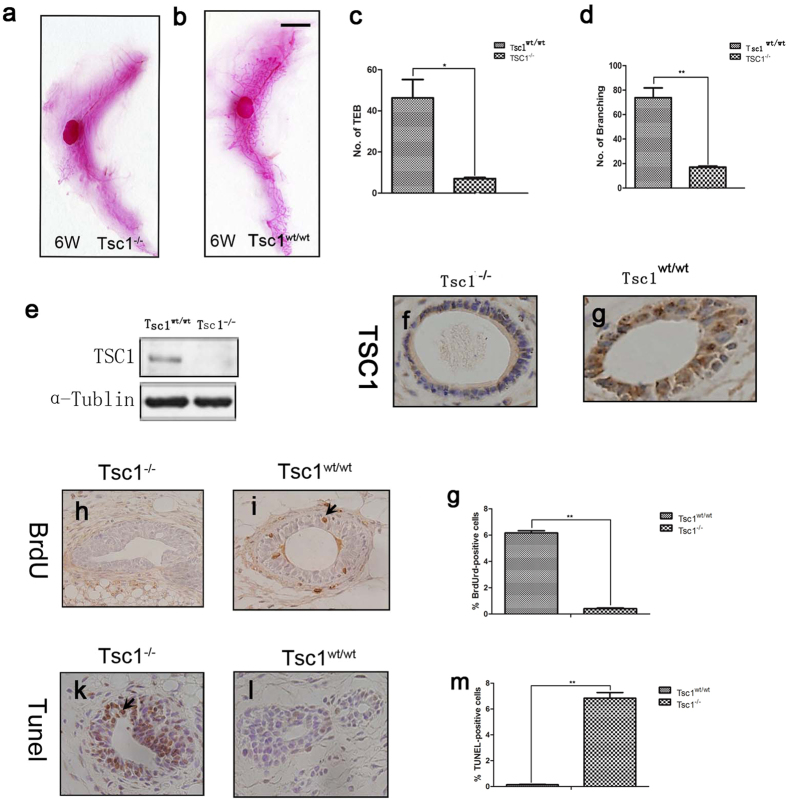

Using a Cre-LoxP conditional knockout strategy, we generated a mouse model with a specific knockout of Tsc1 in mammary epithelium (Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+) to study the role of Tsc1 in mammary development. At the age of 6 weeks, equivalent to puberty, female Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ mice (shortened as Tsc1−/−) and Tsc1wt/wtMMTVCre+ mice (the wild type control, shortened as Tsc1wt/wt) were evaluated by whole mount analysis for their mammary glands morphogenesis. It was evident that the mammary ductal tree was less developed in Tsc1−/− mammary glands than it was in the control Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (Fig. 1a,b), confirmed by quantitative comparison of numbers of terminal end buds (TEBs) and mammary branches between Tsc1−/− and Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (Fig. 1c,d). At the same time, immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry was carried out to confirm that Tsc1 was efficiently knockout in the mammary epithelium of the Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ mice (Fig. 1e–g). To identify the reasons underlying the poor development of Tsc1−/− mammary glands, BrdU incorperation staining assays and TUNEL assays were performed to examine the proliferation and apoptotic status of the mammary cells. As is shown in Fig. 1h–m, the number of BrdU-positive cells was markedly decreased while the number of apoptotic cells was increased in the Tsc1−/− mammary glands, compared with the wild type mammary glands. These data indicated that the pubertal mammary development is impaired in Tsc1−/− mammary glands.

Figure 1. Conditional knockout of Tsc1 in mammary epithelium led to retarted mammary development in mice.

Whole mount staining of the 4th mammary gland of the 6-weeks old female Tsc1−/− mice (a), Tsc1wt/w mice (b) showed that Tsc1 deficiency induced less developed mammary gland. The number of TEBs (c) and branches (d) were compared between Tsc1−/− mammary glands and Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (n = 3). Asterisks indicate the P value (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Expression of TSC1 of mammary glands were detected by immunoblotting (e) and immunohistochemistry (f,g) to confirm the effect of Tsc1 deletion. Immunohistochemical detection of BrdU incorporation was performed to Tsc1−/− mammary glands (h) and Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (i), with comparison of number of BrdU-positive cells of the two genotypes (j) (n = 3). Immunohistochemical detection of TUNEL-staining-positive cells was performed to Tsc1−/− mammary glands (k) and Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (l), with comparison of number of TUNEL-positive cells of the two genotypes (m) (n = 3). Asterisks indicate the P value (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Rapamycin restored the mammary development in Tsc1 −/− mice while suppressed it in Tsc1 wt/wt mice

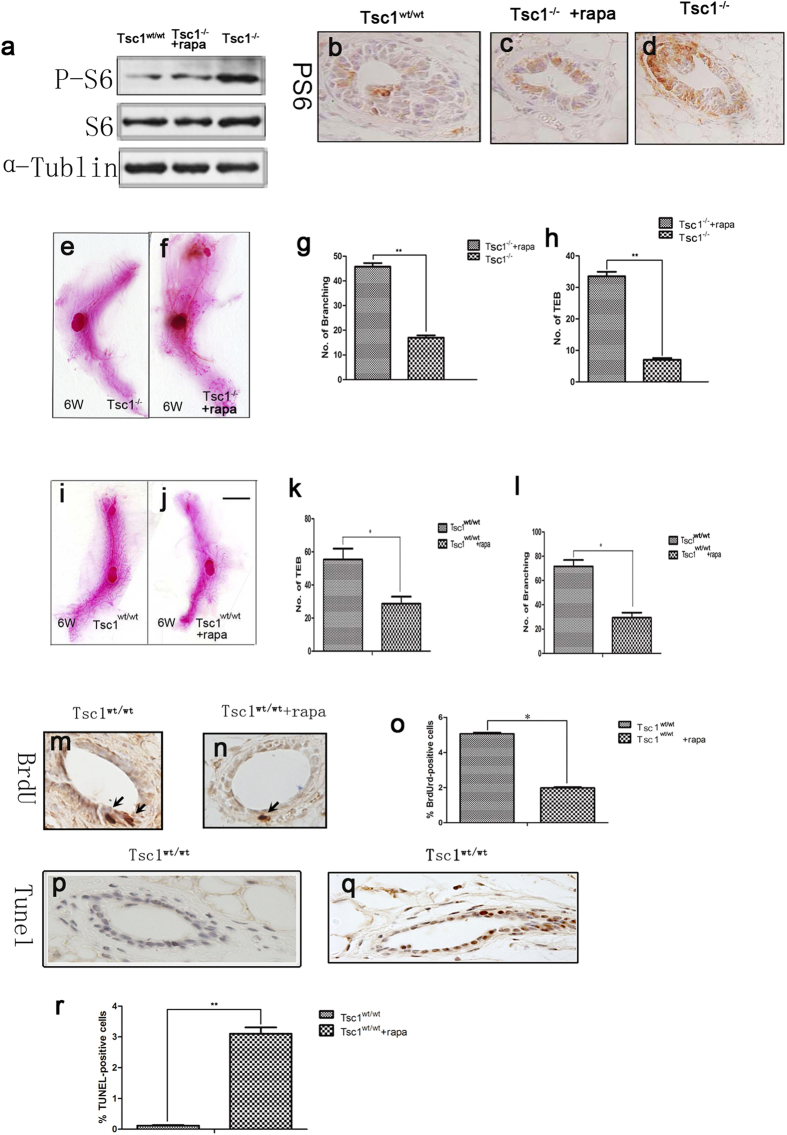

Since TSC1/TSC2 complex is an upstream negative regulator of mTORC1, loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 will result in hyperactivation of mTORC1. In the present model, we found that phosphorylation of S6 (p-S6) , a downstream target of mTORC1, was far more enhanced in Tsc1−/− mammary glands than it was in the Tsc1wt/wt glands (Fig. 2a–d), indicating that mTORC1 of the mammary epithelium is sustained activated by Tsc1 knockout. Rapamycin is a specific inhibitor of mTORC1. We then wonder if it could reverse the phenotype observed in the Tsc1−/− mammary glands. 4-weeks-old Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ female mice along with their Tsc1wt/wtMMTVCre+ counterparts were treated with rapamycin at a dose of 0.1 mg per kilogram of body weight every other day for 2 weeks. Mice of the same genotype at the same age taking the same dose of saline were taken as control. We found that rapamycin treatment apparently reverse the up-regulation of p-S6 in Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium (Fig. 2a,d) and rescued the mammary development of these mice (Fig. 2e,f), proved by increased number of TEBs and branches in the rapamycin-treated Tsc1−/− mammary glands, compared with the saline-treated Tsc1−/− mammary glands (Fig. 2g,h). However, the same dose of rapamycin repressed the mammary development of female wild type mice (Fig. 2i,j), proved by decreased number of TEBs and branches in rapamycin-treated wild type mice, compared with those of saline-treated wild type mice (Fig. 2k,l). Similar to the Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ mice, rapamycin-treated wild type mice showed decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of mammary epithelial cells (Fig. 2m–r). Therefore, a modest activation of mTORC1 plays an important role in normal mammary development. Either sustained activation or inactivation of mTORC1 will impair mammary morphogenesis.

Figure 2. Rapamycin restored the mammary development in Tsc1−/− mice while suppressed it in Tsc1wt/wt mice.

p-S6 was detected by immunoblotting (a) and immunohistochemistry (b–d) in Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands, Tsc1−/− mammary glands and Tsc1−/− mammary glands treated with rapamycin to showed that mTORC1 was activated by Tsc1 deletion and could be reversed by rapamycin. Whole mount staining of the mammary glands of female Tsc1−/− mice treated with saline for 2 weeks and those treated with rapamycin for 2 weeks indicated that rapamycin could rescue the mammary development of Tsc1−/− mice (e,f). Comparison of the number of TEBs and branches between the two groups were showed in (g,h) (n = 3). Asterisks indicate the P value (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Whole mount staining of the mammary glands of female Tsc1wt/wt mice treated with saline for 2 weeks and those treated with rapamycin for 2 weeks indicated that rapamycin suppressed the mammary development of Tsc1wt/wt mice (i,j). Comparison of the number of TEB and branches between the two groups were showed in (k,l) (n = 3). Asterisks indicate the P value (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Immunohistochemical detection of BrdU incorporation was performed in Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (m) and Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands treated with rapamycin (n), with comparison of number of BrdU-positive cells of the two groups (o) (n = 3). Immunohistochemical detection of TUNEL-staining-positive cells was performed to Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands (p) and Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands treated with rapamycin (q), with comparison of number of TUNEL-positive cells of the two groups (r) (n = 3). Asterisks indicate the P value (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

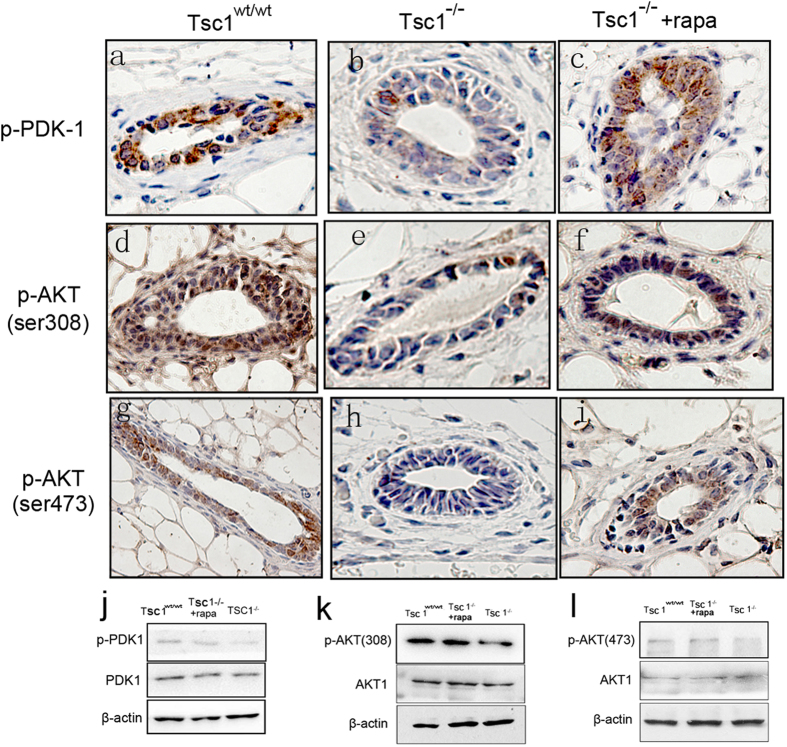

Tsc1 knockout undermined the mammary development through suppression of AKT

PI3K/PDK-1/Akt pathway plays a critical role in mediating extracellular signals to promote cell proliferation and survival. It is well known that AKT activity can be suppressed by activation of mTOC1 through a negative feedback loop mediated by insulin receptor substrate-1(IRS-1), which serves as an adaptor protein up stream of PI3K/PDK-113,14. In this study, phosphorylated PDK-1 (p-PDK-1) and phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT308 and p-AKT473) were all downregulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands, which could be rescued by rapamycin treatment (Fig. 3), suggesting that the inhibition on PI3K/PDK-1/AKT was due to sustained activation of mTORC1. Given the important function of AKT in cell proliferation and survival, we believe that suppressed AKT activity underlined the abnormal mammary development induced by Tsc1 knockout.

Figure 3. Tsc1 knockout undermined the mammary development through suppression of AKT.

Immunohistochemical detection of phosphorylated PDK-1 (a–c), phosphorylated AKT (Ser 308) (d–f), and phosphorylated AKT (Ser 473) (g–i) were performed in Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands, Tsc1−/− mammary glands and Tsc1−/− mammary glands treated with rapamycin. Immunoblotting detection of these phosphorylated proteins were also performed (j–l).

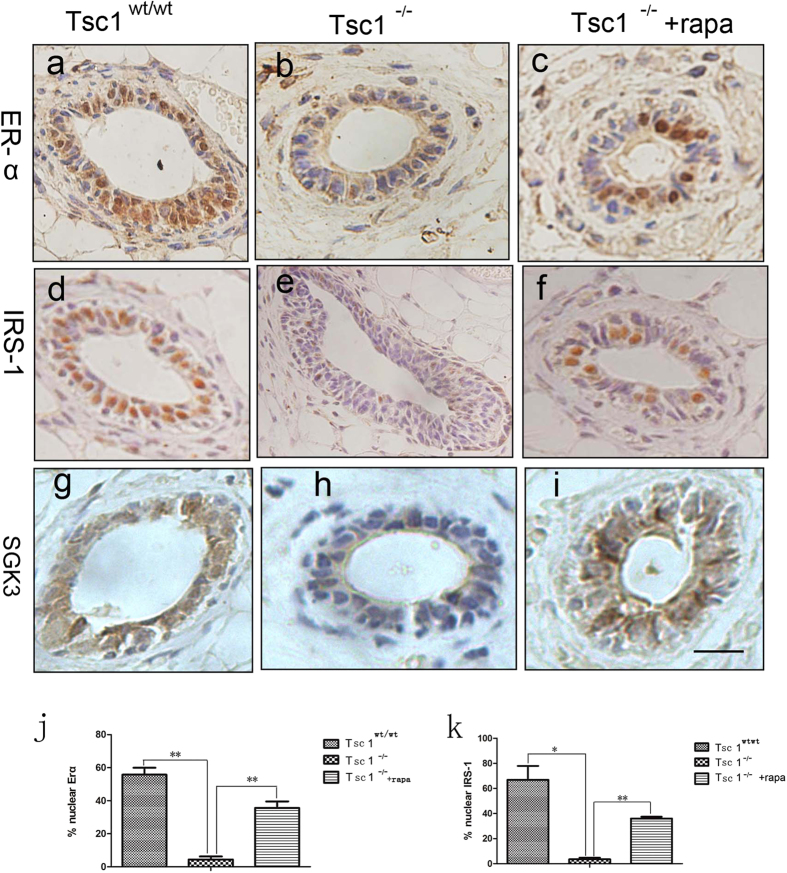

Nuclear ERα and IRS-1 was suppressed in the Tsc1 −/− mammary epithelium

Estrogen is a critical hormone that exerts direct effects on pubertal mammary gland development by stimulating mammary ductal growth15. Estrogen receptors (ER) are broadly expressed in both epithelial and stromal compartments of the mammary gland. Upon activation by E2, ERα translocates to the nucleus and functions as a transcriptional activator15. IRS-1, the adaptor protein up stream of PI3K/PDK-1, has been demonstrated to be activated by estrogen in breast cancer cells, and then translocates to the nucleus with a direct binding with ERα, indicating a crosstalk between the PI3K/PDK-1/AKT pathway and the ERα pathway16,17. Our study found out that both nuclear ERα and IRS-1 are down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands, whereas rapamycin treatment can resist such down-regulation (Fig. 4a–f). SGK3, an ERα transcriptional target that promotes estrogen-mediated cell survival18, was found less expressed in the Tsc1−/− mammary glands, and was also reversed by rapamycin treatment (Fig. 4g–i). These results implicated that the suppressed nuclear ERα and nuclear IRS-1 might also contribute to the impaired mammary development induced by Tsc1 knockout.

Figure 4. Nuclear ERα and IRS-1 was suppressed in the Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium.

Immunohistochemical detection of ERα (a–c), IRS-1 (d–f) and SGK3 (g–i) were performed in Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands, Tsc1−/− mammary glands and rapamycin-treated Tsc1−/− mammary glands. Quantitative analysis of nuclear-ERα-positive cells and nuclear-IRS-1-positive cells in the 3 kinds of mammary glands were showed in (j,k). Asterisks indicate the p value (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

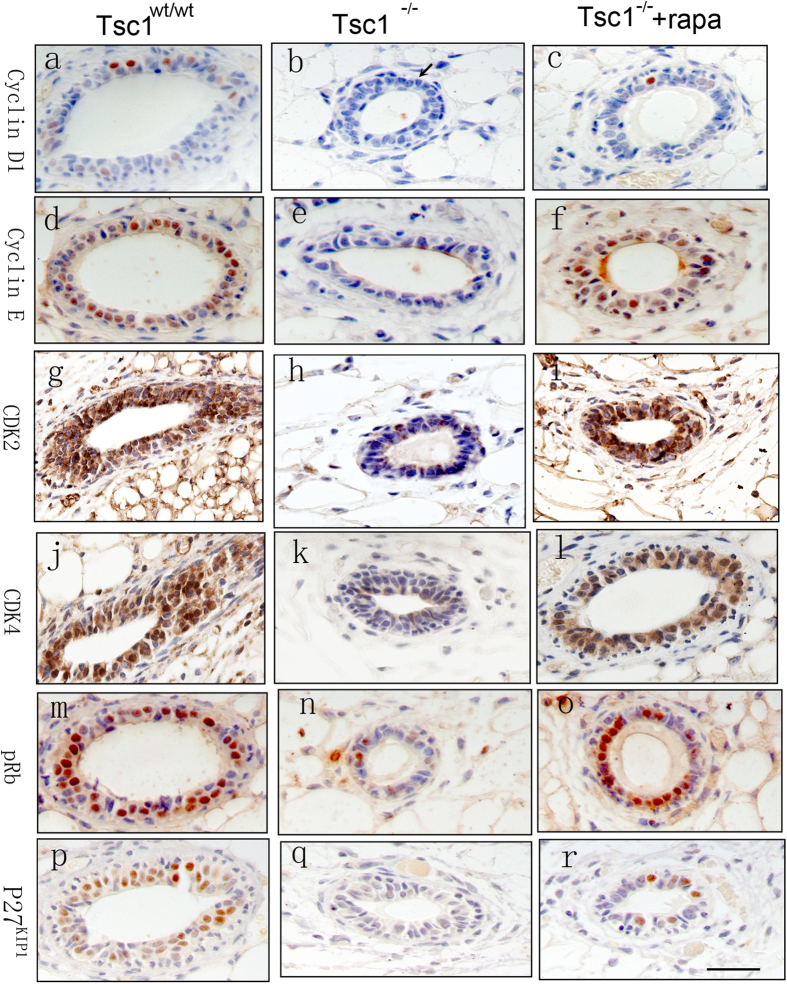

Cell cycle related proteins were down-regulated in the Tsc1 −/− mammary epithelium

According to the present model, loss of Tsc1 reduced the proliferation of mammary epithelial cells, implying that inhibition of cell cycle might be responsible for the reduced proliferation. The expression of several key proteins regulating cell cycle, such as Cyclin D1, Cyclin E, Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Cdk4), their down stream target pRB and the Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p27kip1, were then investigated in the Tsc1−/− mammary glands and their wild-type counterparts. It was found that the positive regulators of cell cycle, Cyclin D1, Cyclin E, CDK2 and CDK4, were all down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands, and could be rescued by rapamycin treatment (Fig. 5a–i). pRB, phosphorylated by Cyclin D/CDK4 and Cyclin E/CDK2, which results in de-repression of cell cycle progression, was also down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands (Fig. 5m–o). Such changes indicated that cell cycle progression was repressed, consistent with the reduced cell proliferation observed in the Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium. Interestingly, the negative regulator of cyclin/CDK, p27kip1 was also down-regulated (Fig. 5p–r), which requires further investigation.

Figure 5. Cell cycle related proteins were down-regulated in the Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium.

Immunohistochemical detection of cyclin D1 (a–c), cyclin E (d–f), CDK2 (g–i), CDK4 (j–l), pRB (m–o) and p27kip1 (p–r) were performed in Tsc1wt/wt mammary glands, Tsc1−/− mammary glands and rapamycin-treated Tsc1−/− mammary glands.

Discussion

The mammary gland, unlike other organs, undergoes most of its branching postnatally with the onset of puberty rather than in utero. Proper branching morphogenesis is fundamental for functional development and differentiation to occur in adulthood15. Hormones and growth factors (GH) play a crucial role in mammary ductal morphogenesis. GH signals through GH receptors (GHR) in stromal fibroblasts of mammary, inducing secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which then signals to the mammary epithelium to promote proliferation19,20. AKT/TSC1/TSC2/mTORC1 is an important pathway transducing the signals from IGF-1 to down stream targets12,13. However the key components of the pathway, such as TSC1/TSC2 and mTORC1, have not been well investigated in normal mammary development, though their roles in breast cancer development have been known better. Using a mouse model with Tsc1 specifically deleted in the mammary epithelium, we found that TSC1 is important for mammary development because a modest activation of mTORC1 is needed for proper mammary gland morphogenesis.

Activation of mTORC1 promotes cellular proliferation and growth7. TSC1/TSC2 complex exerts negative regulation on mTORC1 signaling. Loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 induces constitutive activation of mTORC1, leading to excessive cell proliferation and cell growth. However unlike the hyperplasia phenotypes of Tsc1 deficiency that had been observed in other organs such as the kidney1, Tsc1 deficiency in female mammary epithelium caused decreased ductal branching and TEB formation with less BrdU-positive cells and more apoptotic cells, showed by the present study. Such phenotype could be rescued partially by rapamycin, the specific inhibitor of mTORC1, proving that sustained activation of mTORC1 contributes to the abnormal mammary morphogenesis induced by Tsc1 deficiency. Notably, the same dose of rapamycin repressed the mammary development of female wild type mice (Tsc1wt/wtMMTVCre+), implying that a modest mTORC1 activation is important for normal mammary development, because either sustained activation or inactivation of mTORC1 leads to impaired mammary morphogenesis.

The negative feedback regulation on AKT by activation of mTORC1 may be responsible for the impaired mammary development induced by Tsc1 deficiency. IRS-1, which binds to insulin receptor or insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor upon insulin or IGF-1 stimulation, is required for activation of PI3K in response to such stimulus21. S6K, once activated by mTORC1, phosphorylates IRS-1 at Ser302, which disrupts the interaction of IRS-1 with the receptors, leading to a blockage in insulin signaling to PDK-1, AKT and mTOR22,23. The S6K directed phosphorylation of IRS-1 thus constitutes a negative feedback loop that down-regulates the signaling from insulin receptor to AKT. In the present study, phosphorylated PDK-1 and AKT were all apparently down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands, which could be rescued by rapamycin treatment, suggesting that the suppressed AKT activity was due to the sustained activation of mTORC1. AKT plays critical roles in cell proliferation and survival24. Therefore, inhibition of AKT may contribute to the decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of mammary epithelial cells. In addition, according to the present model, Tsc1−/− mice do not develop breast tumors (the longest observation period reached 6 months), which is supposed to be related with the low level of activated AKT.

Estrogen plays a critical role in pubertal mammary development. Through binding to estrogen receptors (ER) broadly expressed in both epithelial and stromal compartments of mammary glands, estrogen stimulates mammary ductal growth by inducing expression of various growth factors15. Once activated by estrogen, the ERα is able to translocate into the nucleus and bind to DNA to regulate gene expression, known as the genomic effect of ER. Our study showed that nuclear ERα was down-regulated in the Tsc1−/− mammary epithelial cells, which could also be reversed by rapamycin, indicating that the genomic effect of ERα was inhibited by sustained activation of mTORC1. The interaction between PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling and ER signaling has been found in breast cancer cells. Over expression of S6K1, the downstream target of mTORC1, has been reported to regulate ERα by phosphorylating it on serine 167, leading to a transcriptional activation of ERα in breast cancer cells25. Suppressed AKT activity influences ER functions in endocrine-resistant breast cancers26. But how are these two pathways interact with each other to control normal mammary development needs further investigation. According to the present study, inhibition of nuclear ERα may contribute to the Tsc1-deficiency-induced suppressed mammary development. Insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) is an adaptor protein responsible for transducing signals from insulin, IGF-I, growth factors such as EGF and hormones, including growth hormone and estrogen. Not only functions in cytoplasm, IRS-1 also presents in nuclei and contributes to the process of malignant transformation by activating ribosomal RNA biosynthesis, which stimulates overall protein synthesis16,17. IRS-1 has been found to directly bind to ERα and co-transfer to the nuclei of breast cancer cells, indicating a interaction between IRS-1 and ERα in controlling breast cancer development27. Nuclear IRS-1 was also detected in 1.6% of normal mammary epithelium28,29. In the present study, nuclear IRS-1 and ERα were all down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium,which could be reversed by rapamycin, suggesting that their nuclear translocation are all regulated by mTORC1 signaling. The interaction between IRS-1 and ERα may also exist in mammary epithelial cells and contribute to normal mammary development.

The serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase (SGK) isoforms are AKT-independent serine/threonine kinases that locate downstream of PI3K/PDK1, playing important roles in PI3K signaling induced cell growth, proliferation and survival independently of AKT30,31. One of the isoforms, SGK3, can phosphorylate TSC2 and PRAS40, leading to mTORC1 activation32. To our current knowledge, the feed back regulation on SGK3 by mTORC1 activation has not been reported. Here we found that SGK3 is down-regulated in the Tsc1−/− mammary epithelial cells, which can be reversed by rapamycin, implying that a negative feed back regulation may exist between mTORC1 and SGK3. Previous studies also reported that SGK3 is an ERα transcriptional target and promotes estrogen-mediated cell survival of ERα-positive breast cancer cells33. Therefore it is also possible that down regulation of SGK3 in Tsc1−/− mammary epithelia cells is caused by reduced nuclear ERα activity.

Cyclin-CDK complexes play positive roles in driving cell cycle progression34. Cyclin D–CDK4 and cyclin E–CDK2 stimulated in G1 phase cause phosphorylation of RB, which release the RB-mediated inhibition of E2Fs and subsequently drive the cell cycle forward to enter S phase35. Therefore, the down-regulation of cyclin D1, cyclin E, CDK2 and CDK4 observed in the Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium could explain why the cell proliferation was inhibited in Tsc1−/− mammary epithelium. However expression of Cyclin D1 is positively regulated by mTORC136. We speculated that such down-regulation, which could be rescued by rapamycin, might be related to the suppressed AKT activity induced by sustained activation of mTORC1. Consistently, a previous study has reported that Cyclin D1 was less expressed in Akt1-knockout mice mammary glands37. p27kip1 is a negative regulator of cyclin-CDK complexes including Cyclin D–CDK4 and Cyclin E–CDK2. A direct physical association of p27 with Cyclin–CDK complexes can restrain the CDK activity, thus maintain RB in a hypophosphorylated state that sequesters E2F, which hold back the cell from progression in to S phase38. Therefore low expression of p27 is consistent with high cellular proliferation. Multiple human tumors such as breast tumors exhibit abnormally low levels of p27 protein39,40. Decreased p27 levels in breast tumors correlates with a poor patient prognosis41,42. However during mammary glands development, the effects of p27kip1 on cell cycle seemed to depend on the expression level of p27kip1. According to a previous report43, p27+/− mammary glands displayed increased proliferation and delayed involution. But intriguingly, p27−/− mammary glands displayed a decrease in epithelial proliferation with a marked delay in differentiation, similar to the phenotype of the Cyclin D1–deficient animals. We found that p27kip1 was apparently down-regulated in Tsc1−/− mammary glands, which could be reversed by rapamycin, suggesting that the expression of p27kip1 was regulated, at least partially by mTORC1 signaling. Decreased expression of p27kip1 was supposed to correlate with increased proliferation, which however has not been observed in the present model. How is p27kip1 down-regulated by Tsc1 deficiency requires further research.

In conclusion, this study supports the notion that a balanced mTORC1 activity was critical for pubertal mammary gland development in mice. Loss of Tsc1 and consequently sustained activation of mTORC1 results in impaired pubertal mammary gland development. The specific mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin used at a dose of 0.1 mg per kilogram of body weight every other day for 2 weeks can restore the mammary development of the Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ mice, whereas delayed the mammary development of the Tsc1wt/wtMMTVCre+ counterparts. Mechanisms underlying the impaired mammary development induced by Tsc1 deficiency may involve: 1, suppression of AKT by sustained activation of mTORC1; 2, inhibition on nuclear ERα signaling; and 3, down-regulation of Cyclin D1, Cylin E, CDK2 and CDK4, which hold back the cell cycle progression. We speculate that down-regulation of nuclear ERα, Cyclin D1, Cyclin E, CDK2 and CDK4 are related to depressed AKT activity. The negative feed back regulation on AKT by activated mTORC1 probably plays a key role in the retarded mammary development induced by Tsc1 deficiency.

Methods

Animal

Mice harboring the LoxP-flanked Tsc1 (Tsc1L/L) allele (129S4/SvJae background) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Stock No. 005680, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) . MMTVCre+ mice were obtained from Center of Model Animal Research at Nanjing University, China. By mating Tsc1L/L mice with MMTVCre+ mice, Tsc1L/wtMMTVCre+ mice were generated, which were then mated with Tsc1L/L mice to generate Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ mice with Tsc1 specifically knockout in mammary epithelia cells. By mating Tsc1L/wt mice with MMTVCre+ mice, Tsc1wt/wtMMTVCre+ mice were generated. All animals were cared for in accordance with guidelines established by the Southern Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee. All experimental protocols were approved by the Southern Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Rapamycin treatment

The 4-week-old Tsc1L/LMMTVCre+ mice and Tsc1wt/wtMMTVCre+ mice were treated with 0.1 mg/kg rapamycin every other day for 2 weeks by i.p. injections. Counterparts given the same amount of saline were taken as control.

Whole mount staining, TEBs and branches quantification

The entire 4th mammary gland of each mouse was dissected at 6 weeks of age and spread on a glass slide. Samples were fixed with Carnoy’s fixative for 2-4 hours at room temperature, rinsed in 70% ethanol, and then stained overnight at 4 °C with carmine alum. After dehydration, samples were cleared with xylene and mounted. For TEB quantification, TEBs of greater than or equivalent to 0.03 mm2 were counted under a 40 × lens. For branches quantification, the longest primary duct and the secondary duct were counted. Each group took 3 mice to provide the 4th mammary gland, and the TEBs and branches was counted in 3 visual fields per mammary gland under a 40 × lens. The average number of each mammary gland was used for statistical analysis and comparison.

BrdU incorperation assay and TUNEL assay

Mice at 6 weeks of age were injected i.p. with 10 μl/g body weight bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) 4 hours before sacrifice. The entire 4th mammary gland of each mouse was removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2-4 h at 4 °C and processed to paraffin block. Sections (5 μm) were cut, dried at 37 °C overnight and then stored at 4 °C for BrdU and TUNEL analyses. To retrieve nuclear antigens on paraffin-embedded sections, slides were incubated for 20 min in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 90 °C. The sections were blocked with PGB superblock (10% normal goat serum and 10% BSA in 0.5 m PBS) for 2 h at room temperature and incubated with monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (1:1500; Millipore) in PGB diluent (PGB superblock with 1% Triton-X-100) in a humidifier box at 4 ° C overnight followed by incubation with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies. To detect apoptotic nuclei, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were analyzed by TdT digoxigenin nick-end labeling with in situ apoptosis detection kit (Promage) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were placed in pressure cooker (full pressure for 3 min) with appropriate 0.01 M sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval. Subsequently, sections were incubated in blocking solution consisting of 5% BSA and 10% (v/v) normal goat serum in PBS at room temperature for 1 hour. The primary antibodies TSC1((1:100,abclonal), phosphor-S6 (1:100, CST), phospho-PDK1 (1:100, Bioworld), phospho-AKT308 (1:100, Bioworld), phospho-AKT473 (1:100, CST), IRS-1 (1:100, Bioworld), ERα (1:30, Proteintech), cyclin D1 (1:50, Abclonal), cyclin E (1:100, Immunoway), CDK4 (1:100, Abclonal), CDK2 (1:100, Proteintech), p-Rb (1:100, Abclonal) and p27kip1 (1:100, Abclonal) were then applied and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Appropriate secondary antibodies were applied for 1 hour. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Western Blot

The 4th mammary glands excised from mice were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, then lysed in cold RIPA buffer (1 × PBS, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium dexoycholate, 0.1% SDS, protease inhibitor cocktail tablet [Roche] and 1 mM PMSF [Beyotime Biotechnology]). Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 minutes with frequent vortexing and cleared twice by centrifugation (13,200 rpm,10 minutes, 4 °C). Protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked for 60 minutes at room temperature in 5% non-fat milk/Tris-buffered saline/0.1% Tween (TBST). After being washed with TBST, the blots were incubated in primary antibodies for 3 h, which were PS6 (1:2000, CST), S6 (1:2000, CST), TSC1 (1:1000, Proteintech), PDK1(1:1000, ABclonal), phospho-PDK1 (1:1000, Bioworld) phospho-AKT308 (1:1000, Bioworld), phospho-AKT473 (1:1000, CST), AKT1 (1:1000, CST) and β-actin (1:1000, Bioworld). Antibody detection was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (Genstar, Beijing, China) and developed on film.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test, using a SPSS 10.0 software. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Qin, Z. et al. Tsc1 deficiency impairs mammary development in mice by suppression of AKT, nuclear ERa, and cell-cycle-driving proteins. Sci. Rep. 6, 19587; doi: 10.1038/srep19587 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81301848, No. 81270088 and No.81372136).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Z.Q., X.B. And J.L. wrote the main manuscript text; Z.Q., H.Z. and L.Z. prepared the mouse model and performed the experiments; Y.O. contributed to establishment of the mouse model; B.H., B.Y. and Z.Q. helped prepare figures; C.Y., Y.S. and J.G. give guidance to the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Orlova K. A. & Crino P. B. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1184, 87–105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Slegtenhorst M. et al. Interaction between hamartin and tuberin, the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products. Hum Mol Genet. 7, 1053–1057 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienecke R., Konig A. & DeClue J. E. Identification of tuberin, the tuberous sclerosis-2 product. Tuberin possesses specific Rap1GAP activity. J. Biol Chem. 270, 16409–16414 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuto G. et al. The tuberous sclerosis-1 (TSC1) gene product hamartin suppresses cell growth and augments the expression of the TSC2 product tuberin by inhibiting its ubiquitination. Oncogene. 19, 6306–6316 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong-Kopera H. et al. TSC1 stabilizes TSC2 by inhibiting the interaction between TSC2 and the HERC1 ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 281, 8313–8316 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K., Li Y., Xu T. & Guan K. L. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 17, 1829–1834 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R. et al. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 10, 457–468 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E. et al. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 6, 1122–1128 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H. et al. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 110, 163–175 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K., Li Y., Xu T. & Guan K. L. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 17, 1829–1834 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett P. E., Barrow R. K., Cohen N. A., Snyder S. H. & Sabatini D. M. RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95, 1432–1437 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um S. H. et al. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature. 431, 200–205 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington L. S. et al. The TSC1–2 tumor suppressor controls insulin-PI3K signaling via regulation of IRS proteins. J Cell Biol. 166, 213–223 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. P. et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science. 332, 1317–1322 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias H. & Hinck L. Mammary gland development. Rev Dev Biol. 1, 533–557 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss K., Valle L. D., Lassak A. & Trojanek J. Nuclear IRS-1 and Cancer. J Cell Physiol. 227, 2992–3000 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio I. et al. Nuclear IRS-1 predicts tamoxifen response in patients with early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 123, 651–60 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. SGK3 is an estrogen-inducible kinase promoting estrogen-mediated survival of breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 25, 72–82 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego M. I. et al. Prolactin, growth hormone, and epidermal growth factor activate Stat5 in different compartments of mammary tissue and exert different and overlapping developmental effects. Dev Biol. 229, 163–175 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan W. & Kleinberg D. L. Insulin-like growth factor I is essential for terminal end bud formation and ductal morphogenesis during mammary development. Endocrinology. 140, 5075–5081 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X. J. et al. Structure of the insulin receptor substrate IRS-1 defines a unique signal transduction protein. Nature. 352, 73–77 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. H., Lipovsky A. I., Dibble C. C., Sahin M. & Manning B. D. S6K1 regulates GSK3 under conditions of mTOR dependent feedback inhibition of Akt. Mol Cell. 24, 185–197 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craparo A. & Freund R. Gustafson TA 14-3-3 (epsilon) interacts with the insulin-like growth factor I receptor and insulin receptor substrate I in a phosphoserine-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 272, 11663–11669 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez E. & McGraw T. E. The Akt kinases: isoform specificity in metabolism and cancer. Cell Cycle. 8, 2502–2508 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamnik R. L. et al. S6 kinase 1 regulates estrogen receptor alpha in control of breast cancer cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 284, 6361–9 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas R. et al. AKT Antagonist AZD5363 Influences Estrogen Receptor Function in Endocrine-Resistant Breast Cancer and Synergizes with Fulvestrant (ICI182780) In Vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 14, 2035–48 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli C. et al. Nuclear insulin receptor substrate 1 interacts with estrogen receptor alpha at ERE promoters. Oncogene. 23, 7517–7526 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisci D. et al. The estrogen receptor alpha:insulin receptor substrate 1 complex in breast cancer: structurefunction relationships. Ann Oncol . 18, vi81–85 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisci D. et al. Expression of nuclear insulin receptor substrate 1 in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 60, 633–641 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn M. A., Pearson R. B., Hannan R. D. & Sheppard K. E. Second AKT: the rise of SGK in cancer signalling. Growth Factors. 28, 394–408 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier M. & Woodgett J. R. Serum and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinases: variations on a theme. J Cell Biochem. 98, 1391–1407 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn M. A., Pearson R. B., Hannan R. D. & Sheppard K. E. AKT-independent PI3-K signaling in cancer-emerging role for SGK3. Cancer Manag Res . 26, 281–92 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. SGK3 is an estrogen-inducible kinase promoting estrogen-mediated survival of breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 25, 72–82 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Malumbres Genome Biology. 15, 122–131 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin S. M. et al. Deciphering the retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation code. Trends Biochem Sci. 38, 12–19 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averous J. et al. Regulation of cyclin D1 expression by mTORC1 signaling requires eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1. Oncogene. 27, 1106–13 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroulakou I. G. et al. Akt1 ablation inhibits, whereas Akt2 ablation accelerates, the development of mammary adenocarcinomas in mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-ErbB2/neu and MMTV-polyoma middle T transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 67, 167–77 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soos T. J. et al. Formation of p27-CDK complexes during the human mitotic cell cycle. Cell Growth Differ. 7, 135–46 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clurman E. B. & Porter P. New insights into the tumor suppression function of p27Kip1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA . 95, 15158–60 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loda M. et al. Increased proteasome-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 in aggressive colorectal carcinomas., Nat. Med . 3, 231–234 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter P. L. et al. Expression of cell cycle regulators p27Kip1 and cyclin E, alone and in combination, correlate with survival in young breast cancer patients. Nat. Med . 3, 222–225 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P. et al. The cell cycle inhibitor p27 is an independent prognostic marker in small (T1a,b) invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 57, 1259–1263 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka R. S. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) is required for mouse mammary gland morphogenesis and function. J Cell Biol. 153, 917–32 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]