Abstract

Uranium is an essential raw material in nuclear energy generation; however, its use raises concerns about the possibility of severe damage to human health and the natural environment. In this work, we report an ultrasensitive uranyl ion (UO22+) detection method in natural water that uses a plasmonic nanowire interstice (PNI) sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction. UO22+ induces the cleavage of DNAzymes into enzyme strands and released strands, which include Raman-active molecules. A PNI sensor can capture the released strands, providing strong surface-enhanced Raman scattering signal. The combination of a PNI sensor and a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction significantly improves the UO22+ detection performance, resulting in a detection limit of 1 pM and high selectivity. More importantly, the PNI sensor operates perfectly, even in UO22+-contaminated natural water samples. This suggests the potential usefulness of a PNI sensor in practical UO22+-sensing applications. We anticipate that diverse toxic metal ions can be detected by applying various ion-specific DNA-based ligands to PNI sensors.

Uranium, a representative radioactive metal, has been used as the main source of nuclear power generation via nuclear fission1. Uranium can exist in various forms in the environment, such as uranyl fluoride (UO2F2), uranyl tetrafluoride (UF4), uranium dioxide (UO2), and triuranium octoxide (U3O8). The accumulation of these compounds in the human body can lead to severe health problems2. For example, UO2F2 and UF4 cause kidney damage, and UO2 and U3O8 can cause certain cancers and mutations by accumulating in the lungs3. Uranium is also found in diverse forms in aqueous conditions. The uranyl ion (UO22+) is the most soluble and common form4,5. Because UO22+ can disturb organ function by accumulating in the skeleton, kidneys, lungs, and liver6,7, the detection of UO22+ in natural water is very important.

Traditionally, UO22+ has been detected using various physical and chemical techniques, including inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry8, radio spectrometry9, atomic adsorption spectrometry10, and phosphorimetry11. However, these methods present several drawbacks in that they require expensive instruments, involve complicated methods, and are time-consuming. Recently, nanomaterial-based UO22+ sensing methods have been developed by employing fluorescence12,13, electrochemistry14, resonance scattering15,16, colorimetry17, magnetoelasticity18, and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)19,20,21. Among these techniques, SERS offers highly sensitive molecular detection because SERS signals can be obtained from a small number of molecules or even a single molecule located within a sub-10 nm metallic nano-gap (hot spot)22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. This technique also provides molecular fingerprints and causes less photobleaching43,44,45,46,47,48. Nevertheless, there are only a few reported SERS sensors for UO22+ detection, and most of them have not been validated in real environments. Therefore, further improvements in sensitivity, selectivity, and reproducibility are still needed for the practical sensing of UO22+ in a real environment using a SERS sensor.

Here, we report an ultrasensitive UO22+ detection method using a plasmonic nanowire (NW) interstice (PNI) sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction. SERS-based sensing methods are often affected by uncontrolled aggregation and size distribution of nanomaterials, which are detrimental to the reproducibility of the sensor49,50,51. A PNI platform composed of a single-crystalline Au NW with an atomically flat surface has shown improved sensitivity and reproducibility31. By combining the DNAzyme cleaving method with a PNI platform, we quantitatively detected UO22+ with an ultralow detection limit of 1 pM and high selectivity. More importantly, the precise detection of UO22+ was demonstrated in several UO22+-contaminated natural water samples, showing the practical applicability of the PNI sensor.

Results and Discussion

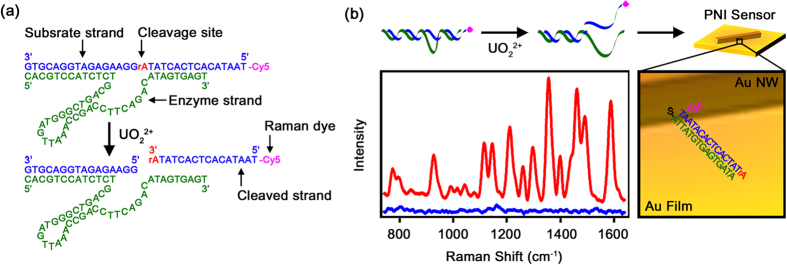

DNA-based ligands, including aptamers and DNAzymes, have been widely used to detect various metal ions because they provide several advantages, such as high affinity, selectivity, stability, and relative ease of modification52,53. In this experiment, we used a DNAzyme, which has the sequence shown in Fig. 1a, for the detection of UO22+. A DNAzyme is composed of an enzyme strand and a substrate strand. The enzyme strand (green) is a specific sequence that can bind to UO22+. The substrate strand (blue) is hybridized with the enzyme strand. In the middle of the substrate strand, a ribose-adenosine (rA) sequence (red) is present. Ribonucleotides are approximately 100,000-fold more susceptible to hydrolytic cleavage than deoxyribonucleotides13. At the 5′ end of the substrate strand, Cy5 (magenta) is present. Cy5 is a well-known Raman reporter for the 633 nm excitation source27,28,29,30,31,32. When UO22+ was added to DNAzyme, UO22+ bound to the enzyme strand, and thus, the rA sequence on the substrate strand was hydrolytically cleaved. The cleaved strand was released from the DNAzyme and then captured by a PNI sensor. The PNI sensor was prepared by laying down a single-crystalline Au NW onto a Au film24 (Fig. 1b). Au NWs were synthesized using a previously reported vapor transport method54 and then modified by the addition of a complementary capture DNA strand to the cleaved strand. The length of capture strand was set as 15 base pairs to increase the hybridization efficiency with cleaved strand55. The PNI sensor with an attached cleaved strand can provide a strong Cy5 SERS signal, enabling the detection of UO22+. The left panel in Fig. 1b shows the result of using a PNI sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction for UO22+ detection. When UO22+ was present in the sample solution at the concentration of 10 nM, 4 major bands at 1185, 1360, 1485, and 1580 cm−1 were clearly detected by the PNI sensor (red spectrum). These bands correspond to the v(C-N)stretch, v(C = C)ring, v(C-C)ring, and v(C = N)stretch of Cy5, respectively28. In contrast, when UO22+ was absent from the sample solution, the PNI sensor exhibited a weak SERS signal (blue spectrum). In this way, UO22+ can be detected from the turn-on of the SERS signal. Generally, turn-on type sensors are more suitable than turn-off type sensors for practical applications because they result in fewer false-positive results17.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of UO22+-specific DNAzyme and cleavage of DNAzyme induced by UO22+ (b) Schematic illustration of UO22+ detection by a PNI sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction. The left panel shows the SERS spectra measured from PNI sensors in the absence of (blue spectrum) and the presence of 10 nM UO22+ (red spectrum).

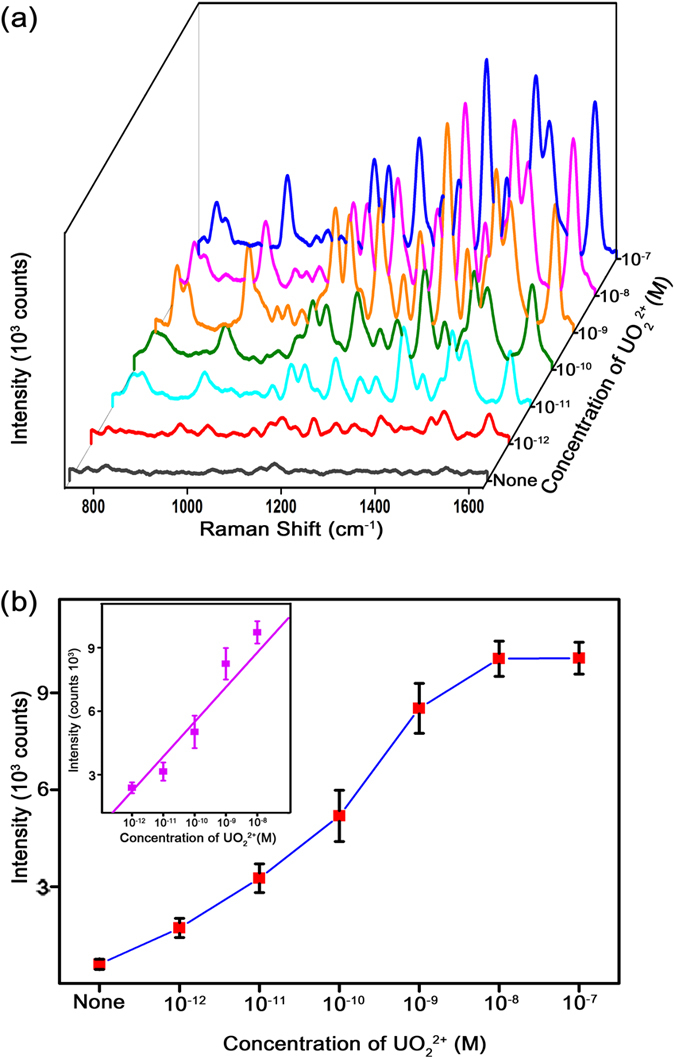

Figure 2a shows the SERS signals measured from the PNI sensors while varying the UO22+ concentration from 1 pM to 100 nM. The samples were prepared by a 1/10 serial dilution, and a blank sample solution was prepared as a control. In the blank sample solution, the PNI sensor provided a weak Cy5 SERS signal (black spectrum in Fig. 2a). In the 1 pM sample, the signal was significantly enhanced (red spectrum in Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows the intensity of the Cy5 1580 cm−1 band plotted as a function of the UO22+ concentration. The SERS signal from the PNI sensor increased as the UO22+ concentration increased, saturating at a concentration of 10 nM. The inset in Fig. 2b shows the dynamic range of the PNI sensor for UO22+ detection. The SERS signal intensity linearly increased within the UO22+ concentration range of 1 pM to 10 nM. This wide dynamic range makes this technique advantageous for the quantitative detection of UO22+. We estimated the detection limit of the PNI sensor to be 1 pM. This detection limit is approximately 1,000-fold lower than the limits of other SERS-based sensors21. Furthermore, the detection limit of this method is comparable to that of the most sensitive detection method, which is based on a resonance scattering spectral technique15.

Figure 2.

(a) SERS spectra of Cy5 measured from PNI sensors when the UO22+ concentration is varied from 1 pM to 100 nM. (b) Intensity of the Cy5 1580 cm−1 band plotted as a function of the UO22+ concentration. The inset provides the dynamic range of the PNI sensor for UO22+ detection. The data represent the mean plus standard deviation from 7 measurements.

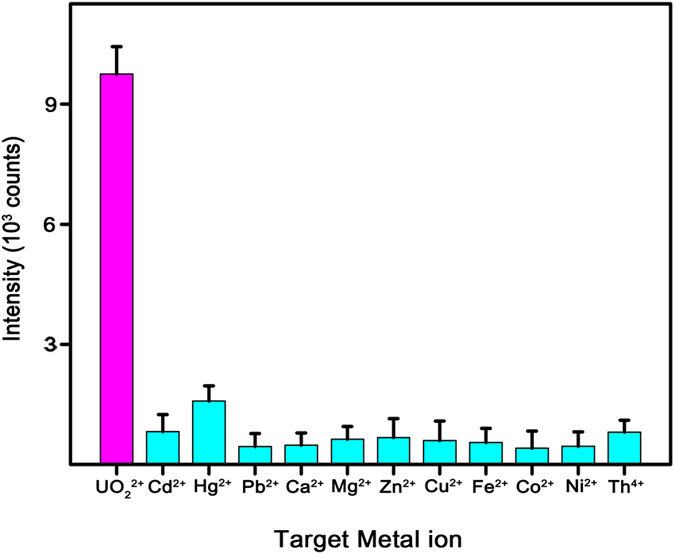

To confirm the selectivity of a PNI sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction, SERS signals were observed from the PNI sensors after mixing DNAzyme with samples containing various metal ions (UO22+, Cd2+, Hg2+, Pb2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Th4+). The concentration of each metal ion was 10 nM. Figure 3 shows the intensity of the Cy5 1580 cm−1 band measured from the PNI sensors for detecting the various metal ions. Remarkable SERS signal was observed only in the presence of UO22+ (magenta bar in Fig. 3), and no distinct SERS signal was observed in the presence of other metal ions (cyan bars in Fig. 3). These results indicate that the proposed detection method is highly specific for UO22+.

Figure 3. Selectivity of a PNI sensor for UO22+ detection.

The tested metal ions are shown on the x axis and their corresponding Cy5 1580 cm−1 band intensities are shown on the y axis. Strong SERS signals were observed only in the presence of UO22+ (magenta bar) and weak SERS signals were observed in the presence of other metal ions (cyan bars). The data represent the mean plus standard deviation from 7 measurements.

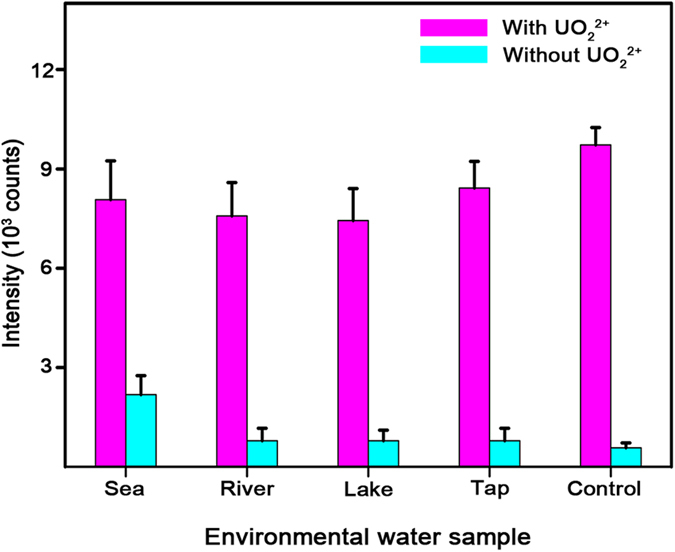

Finally, we examined the applicability of a PNI sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction to detect UO22+ in natural water. The natural water samples were obtained from various environments, including a sea, a river, a lake, and a tap. Buffer solution was also prepared as a control. Figure 4 shows the intensities of the Cy5 1580 cm−1 band measured from the PNI sensors after mixing DNAzyme with the natural water samples. The magenta bars represent the natural water samples spiked with UO22+ and the cyan bars represent the as-collected natural water samples. Strong SERS signals were observed only after the addition of UO22+ into the natural water samples. Without UO22+, SERS signals were rarely observed. Note that the DNAzyme is sensitive to ionic strength56. The DNAzyme is in the lock-and key mode at the ionic strength of 100 mM or higher56. In addition, the concentration of Mg2+ can affect the DNAzyme activity56. At the lower concentration of 2 mM, the activity is promoted. On the other hand, the activity is inhibited at the higher concentration of 2 mM. In this experiment, the DNAzyme solution and natural water sample were mixed with 9:1 volume ratio before the SERS measurement. The ionic strengths of the mixtures are calculated as 246.43 mM (sea), 131.81 mM (river), 134.72 mM (lake), and 132.07 mM (tap) according to the inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and ion chromatography (IC) data of natural water samples (Table S1 and S2 in supplementary information). The concentrations of Mg2+ in the mixtures are 1.31 mM (sea), 0.01 mM (river), 0.02 mM (lake), and 0.01 mM (tap). Since the ionic strengths of mixtures are higher than 100 mM and the concentrations of Mg2+ in the mixtures are below 2 mM, the PNI sensor combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction can detect UO22+ successfully even in natural water samples. The USA’s limit for UO22+ in drinking water is 30 μg/L (approximately 100 nM), however, the long-term consumption and exposure to water that contains UO22+, even at concentrations below this limit, can cause severe toxicity and serious diseases57. We anticipate that the present method can be employed for practical UO22+ detection and aid in the prevention of environmental pollution and human diseases caused by UO22+.

Figure 4. Applicability of a PNI sensor for UO22+ detection in natural water.

Natural water samples are shown on the x axis and their corresponding Cy5 1580 cm−1 band intensities are shown on the y axis. The magenta bars represent the natural water samples spiked with UO22+ and the cyan bars represent the as-collected natural water samples. The spiked UO22+ concentration was 10 nM. The strong SERS signals were observed only after the addition of UO22+ into the natural water samples. The data represent the mean plus standard deviation from 7 measurements.

Conclusion

We detected UO22+ by combining an ultrasensitive PNI platform with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction. The DNAzyme specifically reacted with UO22+ and released a cleaved strand. The PNI sensor sensitively captured the cleaved strand, which enabled the detection of UO22+. We quantitatively detected UO22+ with an ultralow detection limit of 1 pM and high selectivity. Moreover, this method enables the detection of UO22+ in various natural water sources, such as sea, lake, river, and tap. A PNI sensor that can precisely detect small quantities of UO22+ in natural water is expected to reveal many environmental pollutants, and hence minimize damage to the human body caused by UO22+ exposure.

Methods

Materials

Purified DNA was purchased from Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea). Hg(Ac)2, Mg(Ac)2, Ca(Ac)2, CrCl2, FeCl2, Co(Ac)2, NiCl2, CuCl2, Zn(Ac)2, Cd(Ac)2, Pb(Ac)2, UO2(Ac)2, Au powder (99.99%), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Th(NO3)4 was purchased from Merck. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Gibco. The natural water samples were collected from the west sea of South Korea, the Gap River, and the pond at KAIST. Samples were centrifuged to remove impurities.

Preparation of DNAzyme

The sequence of the substrate strand is 5′-Cy5-TAATACACTCACTAT(rA)GGAAGAGATGGACGTG-3′, and the sequence of the enzyme strand is 5′-CACGTCCATCTCTGCAGTCGGGTAGTTAAACCGACCTTCAGACATAGTGAGT-3′. The sequence of the capture strand is 5′-ATAGTGAGTGTATTA-SH-3′. The substrate and enzyme strands were mixed in a 1× PBS solution (pH 7.4) at the same molar concentration (10 μM each). The hybrid solutions were heated at 95 °C for 10 min and slowly cooled to room temperature.

Synthesis of single-crystalline Au NWs

Single-crystalline Au NWs were synthesized on a c-cut sapphire substrate in a horizontal quartz tube furnace system following the chemical vapor transport method described in a previous report54. An alumina boat containing an Au powder was positioned directly below the heat source. The sapphire substrate was placed a few centimeters downstream from the alumina boat. The heating zone was brought to 1100 °C while the chamber pressure was maintained at 3–5 Torr. Ar gas flowing at 100 sccm was used to transport the Au vapor. Au NWs were grown on the sapphire substrate over a 1 h period.

Preparation of PNI sensors

Au film substrates were prepared on Si substrates by electron beam-assisted deposition of a 10 nm thick film of Cr followed by a 300 nm thick film of Au. The prepared Au films were SERS-inactive by themselves24. The Au films were then cut to 1 cm2 for PNI sensor fabrication. To prepare the capture probe DNA-attached Au NWs, as-synthesized NWs were incubated with 5 mM captured DNA in 1 M KH2PO4 buffer (pH 6.75) at room temperature for 12 h. Next, the Au NWs were rinsed with a 0.2% (w/v) SDS solution for 5 min. The capture probe DNA-attached Au NWs were then transferred onto Au films by a simple attachment and detachment process30. Briefly, the NW-grown c-cut sapphire substrates were inverted onto Au film substrates containing medium. Before both substrates were overlapped, a drop of distilled water was applied as a lubricant. The sapphire substrates were then pushed gently and, after a few seconds, detached. After the attachment and detachment process, the remaining water was dried under flowing N2 gas.

Detection of UO2 2+ using PNI sensors combined with a DNAzyme-cleaved reaction

DNAzyme in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) with RNase-free water was mixed with sample solutions containing 0.27% (w/v) HNO3 and incubated for 10 min. The pH of the mixed solution was maintained at 5.49 and its ionic strength was 146.43 mM. To stop the enzymatic reaction by shifting the pH of the mixture, 0.1 mM Tris-acetate solution was added. Then, the mixture was dropped onto the PNI sensor and allowed to stand for 2 h. To remove excess DNA, the sensor was rinsed with a 0.2% (w/v) SDS solution for 5 min and then rinsed twice with distilled deionized water.

Instrumentation

SERS spectra were measured using a micro-Raman system on an Olympus BX41 microscope. A 633 nm He/Ne laser (Melles Griot) was used as an excitation source, and the laser was focused on samples through a 100× objective (NA = 0.7, Mitutoyo). The laser power directed at the sample was 0.4 mW. The SERS signals were recorded with a thermodynamically cooled electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (Andor) mounted on the spectrometer with a 1200 groove/mm grating. The acquisition time for all SERS spectra was 60 s. A holographic notch filter was used to reject laser light. The concentration of metal ion in natural water samples was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES 720, Agilent) and ion chromatography (881 Compact IC pro, Metrohm Ltd.).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gwak, R. et al. Precisely Determining Ultralow level UO22+ in Natural Water with Plasmonic Nanowire Interstice Sensor. Sci. Rep. 6, 19646; doi: 10.1038/srep19646 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Public Welfare & Safety research program (NRF-2012M3A2A1051682, NRF-2012M3A2A1051686) through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (MSIP), Global Frontier Project (H-GUARD_2014M3A6B2060489) through the Center for BioNano Health-Guard funded by MSIP, and KRIBB initiative Research Program. H.K. is the recipient of Global Ph.D. Fellowship (NRF-2011–0030947). Prof. Jong-Il Yun’s RCLS (RadioChemistry and Laser Spectroscopy) lab at department of Nuclear & Quantum Engineering (KAIST, Daejeon) assisted the UO22+ and Th4+ related experiments.

Footnotes

Author Contributions R.G. and H.K. conceived the main idea and executed the project equally. S.Y. and S.L. contributed to the treatment of biomaterials and related discussion. G. L., M. L. and C.R. contributed to the metal ions related discussion. T.K. and B.K. supervised the study. All authors also contributed to the manuscript preparations

References

- Cantaluppi C. & Degetto S. Civilian and military uses of depleted uranium: environmental and health problems. ANNALI DI CHIMICA-ROMA - 90, 665–676 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft E. S. et al. Depleted and natural uranium: chemistry and toxicological effects. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 7, 297–317 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazel V., Houpert P. & Ansoborlo E. Effect of U3O8 specific surface area on in vitro dissolution, biokinetics, and dose coefficients. Radiation protection dosimetry 79, 39–42 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard S. C. & Evenden W. G. Bioavailability indices for uranium: effect of concentration in eleven soils. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 23, 117–124 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P. & Gu B. Extraction of oxidized and reduced forms of uranium from contaminated soils: Effects of carbonate concentration and pH. Environmental science & technology 39, 4435–4440 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisenne I., Perry P. & Harley N. Uranium in humans. Radiation Protection Dosimetry 24, 127–131 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Zamora M. L., Tracy B., Zielinski J., Meyerhof D. & Moss M. Chronic ingestion of uranium in drinking water: a study of kidney bioeffects in humans. Toxicological Sciences 43, 68–77 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomer D. & Powell M. Determination of uranium in environmental samples using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry 59, 2810–2813 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzbecher J. & Ryen D. E. Determination of uranium by thermal and epithermal neutron activation in natural waters and in human urine. Analytica Chimica Acta 119, 405–408 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Mlakar M. & Branica M. Stripping voltammetric determination of trace levels of uranium by synergic adsorption. Analytica chimica acta 221, 279–287 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Brina R. & Miller A. G. Direct detection of trace levels of uranium by laser-induced kinetic phosphorimetry. Analytical Chemistry 64, 1413–1418 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Hwang K., Lan T. & Lu Y. A DNAzyme-gold nanoparticle probe for uranyl ion in living cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 135, 5254–5257 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. A catalytic beacon sensor for uranium with parts-per-trillion sensitivity and millionfold selectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 2056–2061 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziółkowski R., Górski Ł., Oszwałdowski S. & Malinowska E. Electrochemical uranyl biosensor with DNA oligonucleotides as receptor layer. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 402, 2259–2266 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. et al. Free-labeled nanogold catalytic detection of trace UO22+ based on the aptamer reaction and gold particle resonance scattering effect. Plasmonics 7, 185–190 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. et al. Resonance light scattering determination of uranyl based on labeled DNAzyme–gold nanoparticle system. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 110, 419–424 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Wang Z., Liu J. & Lu Y. Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric sensors for uranyl (UO22+): Development and comparison of labeled and label-free DNAzyme-gold nanoparticle systems. Journal of the American Chemical Society 130, 14217–14226 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J.-C. et al. A wireless magnetoelastic sensor for uranyl using DNAzyme–graphene oxide and gold nanoparticles-based amplification. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 188, 147–155 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Bao L., Mahurin S., Haire R. & Dai S. Silver-doped sol-gel film as a surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrate for detection of uranyl and neptunyl ions. Analytical chemistry 75, 6614–6620 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S. et al. Silver nanoparticle decorated reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanosheet: a platform for SERS based low-level detection of uranyl ion. ACS applied materials & interfaces 5, 8724–8732 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. et al. A label-free nanogold DNAzyme-cleaved surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering method for trace UO22+ using rhodamine 6G as probe. Plasmonics 8, 803–810 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp K. et al. Single molecule detection using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Physical review letters 78, 1667 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Nie S. & Emory S. R. Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Science 275, 1102–1106 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon I. et al. Single nanowire on a film as an efficient SERS-active platform. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 758–762 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T. et al. Creating well-defined hot spots for surface-enhanced Raman scattering by single-crystalline noble metal nanowire pairs. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 113, 7492–7496 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-H. et al. A well-ordered flower-like gold nanostructure for integrated sensors via surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Nanotechnology 20, 235302 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T., Yoo S. M., Yoon I., Lee S. Y. & Kim B. Patterned multiplex pathogen DNA detection by Au particle-on-wire SERS sensor. Nano letters 10, 1189–1193 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T. et al. Au Nanowire‐on‐Film SERRS Sensor for Ultrasensitive Hg2+ Detection. Chemistry-A European Journal 17, 2211–2214 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. M. et al. Combining a nanowire SERRS sensor and a target recycling reaction for ultrasensitive and multiplex identification of pathogenic fungi. Small 7, 3371–3376 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. et al. Facile Fabrication of Multi-targeted and Stable Biochemical SERS Sensors. Chemistry-A Asian Journal 8, 3010–3014 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T. et al. Ultra‐Specific Zeptomole MicroRNA Detection by Plasmonic Nanowire Interstice Sensor with Bi‐Temperature Hybridization. Small 10, 4200–4206 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T. et al. Single-step multiplex detection of toxic metal ions by Au nanowires-on-chip sensor using reporter elimination. Lab on a Chip 12, 3077–3081 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol M.-L. et al. A nanoforest structure for practical surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates. Nanotechnology 23, 095301 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Yang P., Xu H. & Zheng H. Surface enhanced fluorescence and Raman scattering by gold nanoparticle dimers and trimers. Journal of Applied Physics 113, 033102 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Seol M.-L. et al. Multi-layer nanogap array for high-performance SERS substrate. Nanotechnology 22, 235303 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J. et al. SERS-active nanoparticles for sensitive and selective detection of cadmium ion (Cd2+). Chemistry of Materials 23, 4756–4764 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Ko H., Singamaneni S., Gunawidjaja R. & Tsukruk V. V. Nanoporous membranes with mixed nanoclusters for Raman-based label-free monitoring of peroxide compounds. Analytical chemistry 81, 5740–5748 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M. K. et al. pH‐Triggered SERS via Modulated Plasmonic Coupling in Individual Bimetallic Nanocobs. Small 7, 1192–1198 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon H., Lee S., Son S. W., Oh C. H. & Choo J. Highly sensitive immunoassay of lung cancer marker carcinoembryonic antigen using surface-enhanced Raman scattering of hollow gold nanospheres. Analytical chemistry 81, 3029–3034 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E., Jeon J., Yu J., Lee C. & Choo J. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering aptasensor for ultrasensitive trace analysis of bisphenol A. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 64, 560–565 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-H., You M.-H., Kim G.-H. & Nam J.-M. Plasmonic Nanosnowmen with a Conductive Junction as Highly Tunable Nanoantenna Structures and Sensitive, Quantitative and Multiplexable Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Probes. Nano letters 14, 6217–6225 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K. D. et al. A high‐throughput method for controlled hot‐spot fabrication in SERS‐active gold nanoparticle dimer arrays. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 40, 2171–2175 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman S. L., Frontiera R. R., Henry A.-I., Dieringer J. A. & Van Duyne R. P. Creating, characterizing, and controlling chemistry with SERS hot spots. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15, 21–36 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haes A. J., Zou S., Schatz G. C. & Van Duyne R. P. A nanoscale optical biosensor: the long range distance dependence of the localized surface plasmon resonance of noble metal nanoparticles. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 108, 109–116 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Moskovits M. Surface‐enhanced Raman spectroscopy: a brief retrospective. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 36, 485–496 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Jain P. K., Huang X., El-Sayed I. H. & El-Sayed M. A. Review of some interesting surface plasmon resonance-enhanced properties of noble metal nanoparticles and their applications to biosystems. Plasmonics 2, 107–118 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Lee J.-H., Jin S. M., Suh Y. D. & Nam J.-M. Single-Molecule and Single-Particle-Based Correlation Studies between Localized Surface Plasmons of Dimeric Nanostructures with ∼1 nm Gap and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Nano letters 13, 6113–6121 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J. et al. Sub-attomolar HIV-1 DNA detection using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Analyst 135, 1084–1089 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. et al. Etching and dimerization: a simple and versatile route to dimers of silver nanospheres with a range of sizes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 49, 164–168 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence T. A. et al. Rapid, solution-based characterization of optimized SERS nanoparticle substrates. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 162–169 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X. et al. A Molecular Beacon‐Based Signal‐Off Surface‐Enhanced Raman Scattering Strategy for Highly Sensitive, Reproducible, and Multiplexed DNA Detection. Small 9, 2493–2499 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman S. K. In vitro selection, characterization, and application of deoxyribozymes that cleave RNA. Nucleic acids research 33, 6151–6163 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. K., Liu J., He Y. & Lu Y. Biochemical Characterization of a Uranyl Ion‐Specific DNAzyme. ChemBioChem 10, 486–492 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo Y. et al. Steering epitaxial alignment of Au, Pd, and AuPd nanowire arrays by atom flux change. Nano letters 10, 432–438 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham N. R. & Zuker M. DINAMelt web server for nucleic acid melting prediction. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, W577–W581 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. & Lu Y. Metal-Ion-Dependent Folding of a Uranyl-Specific DNAzyme: Insight into Function from Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Studies. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 13732–13742 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. Uranium in drinking-water: Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality. (2004).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.