Abstract

The ventricular conduction system (VCS) orchestrates the harmonious contraction in every heartbeat. Defects in the VCS are often associated with life-threatening arrhythmias and also promote adverse remodeling in heart disease. We have previously established that the Irx3 homeobox gene regulates rapid electrical propagation in the VCS by modulating the transcription of gap junction proteins Cx40 and Cx43. However, it is unknown whether other factors contribute to the conduction defects observed in Irx3 knockout (Irx3−/−) mice. In this study, we show that during the early postnatal period, Irx3−/− mice develop morphological defects in the VCS which are temporally dissociated from changes in gap junction expression. These morphological defects were accompanied with progressive changes in the cardiac electrocardiogram including right bundle branch block. Hypoplastic VCS was not associated with increased apoptosis of VCS cardiomyocytes but with a lack of recruitment and maturation of ventricular cardiomyocytes into the VCS. Computational analysis followed by functional verification revealed that Irx3 promotes VCS-enriched transcripts targeted by Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5. Altogether, these results indicate that, in addition to ensuring the appropriate expression of gap junctional channels in the VCS, Irx3 is necessary for the postnatal maturation of the VCS, possibly via its interactions with Tbx5 and Nkx2.5.

The ventricular conduction system (VCS), comprised of His-bundle, bundle branches, and Purkinje fiber network, plays a critical role in rapid electric propagation through the ventricles of the heart1. It ensures proper electrical activation from apex to base, which orchestrates efficient contraction and pumping of the chambers of the heart. Defects in the VCS are clinically important, either in isolation or in association with heart failure, due to promotion of arrhythmias and acceleration of disease processes2.

Development of the VCS is coordinated by the appropriate spatiotemporal activation of several cardiac transcription factors, such as Nkx2.53,4, Tbx35,6, Tbx57, Id28, HF-1b9 and Hopx10. Loss of these transcription factors leads to various conduction defects including atrioventricular block and bundle branch blocks. Of particular note for our studies is the observation that haploinsufficiency of Nkx2.5 (Nkx2.5+/−) or Tbx5 (Tbx5+/−) leads to conduction defects with increased susceptibility to arrhythmias4,11 in association with anatomical hypoplasia of the cardiac conduction system4,7,12. The limited impact of Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 deficiency on the VCS, despite the expression of these transcription factors through the working myocardium suggests that some unknown VCS-specific molecules cooperate with Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 in the regulation of VCS function and development.

Recently, we have demonstrated that Irx3, a member of the Iroquois family of transcription factors13, regulates electrical propagation of the ventricles14 by modulating the transcription of gap junction genes in the VCS (i.e. Gja5 and Gja1 which encode for Cx40 and Cx43, respectively). In addition, a recent study has identified two novel IRX3 mutations in patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and demonstrated that these mutations resulted in impaired transcriptional regulation of Gja515. However, it was not clear whether the right bundle branch block (RBBB) as well as the pattern of reduced ventricular conduction velocity seen in these studies could be explained entirely by abnormal gap junction expression. Specifically, we found that, consistent with previous studies16,17, the conduction deficiencies seen in Cx40 heterozygous mutant mice were not as severe as seen in mice lacking Irx3 despite having similar reductions in Cx40 expression. In the present study, we show that Irx3−/− mice exhibit progressive changes in electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings during the early postnatal period, which is accompanied by structural deterioration of the VCS, similar to the developmental changes observed in Nkx2.5+/− mice4,12 and that these defects are temporally distinct from the effects of the loss of Irx3 on gap junction expression. Furthermore, we observed that Irx3 interacts with Tbx5, in addition to Nkx2.5 as we showed previously14, and demonstrate that Irx3 regulates the expression of VCS-enriched genes to which Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 bind. Together, these results suggest that Irx3 plays an essential role in the postnatal maturation of the VCS, possibly via its interactions with Tbx5 and Nkx2.5.

Results

Loss of Irx3 leads to structural defects in the ventricular conduction system of adult mouse heart

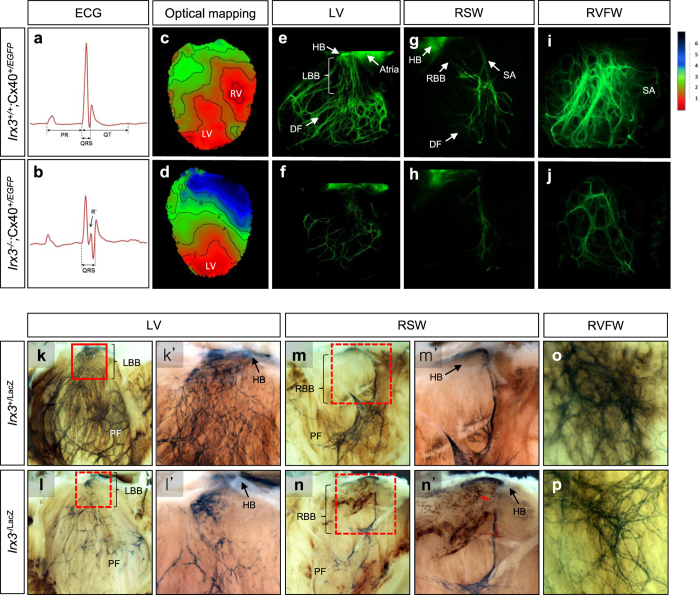

We previously established that Irx3−/− mice showed ~2-fold reductions in Cx40, the major gap junction channel in the VCS, in association with delayed ventricular activation with prolonged QRS intervals and RBBB in 83% of the mice14. On the other hand, previous studies17,18, as well as the data presented below, revealed that mice lacking one Cx40 allele, which are expected to have a ~50% reduction in Cx40 expression, do not show noticeable electrophysiological defects. These findings18 suggest that the electrical disturbances seen in Irx3−/− mice cannot be explained solely by reductions in Cx40 expression. Given the fact that Irx3 interacts with Nkx2.514 and that conduction defects in mice with Nkx2.5 haploinsufficiency are linked to developmental deterioration of the His-Purkinje structure4,7,8,12, we considered the possibility that Irx3 might also regulate VCS morphology. To test this hypothesis, we crossed Irx3−/− mice with mice expressing GFP under the Gja5 (Cx40) promoter (i.e. Cx40+/EGFP) to allow visualization of the VCS16. As shown in previous studies16,17, adult Cx40+/EGFP mice at 10–12 weeks of age, which have one Cx40 allele along with two wild-type Irx3 alleles (i.e. Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP), displayed normal surface ECG signals, indistinguishable from wild type (Irx3+/+;Cx40+/+) mice (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, the ECG recordings in Cx40+/EGFP mice lacking Irx3 (i.e. Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP) were characterized by prolonged QRS intervals accompanied by R-notches (R’) (Fig. 1b), as expected for mice lacking Irx314. In addition, Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP ventricles had slower ventricular activation patterns as well as right bundle branch block (i.e. no ‘breakthrough’ in the right ventricle; RBBB), which is never observed in Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP ventricles (Fig. 1c, d).

Figure 1. Loss of Irx3 leads to abnormal electrical activation of the ventricles and morphological defects of the VCS.

(a,b) Representative surface ECG traces show QRS prolongation and notched R’ wave in 10–12 week old Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice (b) compared to Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP mice (a–d). Optical mapping results in the apical four-chamber view. Isochrone lines with 0.5 ms intervals mark areas where depolarization reached 50% intensity. Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP hearts show simultaneous electrical breakthroughs in both LV and RV with depolarization proceeding in an apex-to-base direction, whereas Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts show a breakthroughs only present in left ventricle (LV) and lack in right ventricle (RV), suggestive of RBB block. (e–j) Fluorescence images of the VCS visualized using 10–12 week old adult mice expressing Cx40-promoter driven EGFP (Cx40+/EGFP). Compared to Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP mice (e,g,i), Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice show reduced fiber densities and fluorescence intensity in the VCS of the left ventricle (f) and right ventricular septal and free walls (RSW and RVFW, respectively) (h,j). The morphology of the VCS was further compared between Irx3+/LacZ and Irx3−/LacZ mice. In Irx3+/LacZ heart, β-gal staining of Irx3 expressing cells marked His-Purkinje system in LV (k) RSW (m) and RVFW (o). On the other hand, VCS morphology of Irx3−/LacZ heart was severely compromised in LV (l) RSW (n) and RVFW (p) with reduced number and density of fibers in bundle branches and distal Purkinje fiber networks. As marked by a red arrowhead (n’), RBB of Irx3−/LacZ heart is found disconnected in many cases. k’,l’,m’,n’ illustrate magnification of framed in panels. HB, His-bundle; LBB, left bundle branch; DF, distal fiber; RBB, right bundle branch; SA, septal artery; and PF, Purkinje fibers.

By imaging the GFP fluorescence images of the left and right bundle branches as well as Purkinje fiber networks, using a previously published technique16, we found that Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mouse hearts had marked reductions in VCS fiber densities throughout the ventricles compared to those of Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP hearts (Fig. 1e–j). In addition, the right bundle branch was absent in many Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts, which correlated with, and explained RBBB in these mice (Fig. 1h). In the remaining VCS fibers, GFP fluorescence intensity was reduced by 58 ± 3% in the left bundle branches and by 35.1 ± 4.5% in the distal fibers of Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts compared to their counterparts in the Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP mice (Supplementary Fig. 1). These reductions of fluorescence intensity in the fibers of Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts are consistent with our previous study showing that Irx3 positively regulates Cx40 gene expression14. Indeed, the fluorescence of Cx40 promoter-dependent GFP expression are not different between Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice in either the atria or coronary arteries, which both express Cx40 but not Irx3. Furthermore, Irx3+/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice did not show reductions in the density or fluorescence intensity of fibers in the VCS, compared to Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP mice, suggesting that the loss of one Irx3 allele is insufficient to cause a measurable decrease in Cx40 promoter activity.

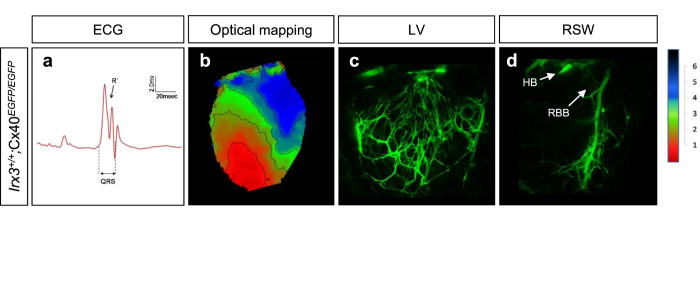

Since the morphological measurements made using GFP to visualize the VCS could be influenced by the known effects of Irx3 on the Cx40 promoter14, we sought to further confirm a role for Irx3 in VCS morphology using mice expressing LacZ was under the control of the Irx3 promoter in place of Irx3. These mice express one LacZ allele and one Irx3 allele (Irx3+/LacZ) which allowed robust delineation of the VCS, characterized by an asymmetric morphology of the Bundle of His with numerous fascicles in the left bundle branch (LBB) and a single fascicle in the RBB along with an elaborate Purkinje fiber network (Fig. 1k,m,o). In contrast to the Cx40+/EGFP mice, Irx3+/LacZ hearts showed no lacZ staining in either the atria or coronary arteries. More importantly, the Irx3−/LacZ mice showed marked reductions in the number of LBB fascicles and Purkinje fibers (Fig. 1l, p), as seen in the Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice. Irx3−/LacZ mice also showed disconnections within, or the complete absence of, RBB (Fig. 1n and Supplemental Fig. 2). Together, these results suggest that Irx3 is required for the maintenance of the VCS and that the morphological defects in the VCS seen in Irx3−/− mice do not arise from changes in the Cx40 expression levels. This suggestion is further supported by studies in mice lacking Cx40 (i.e. Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP). Since Cx40 is the major connexin in the VCS16,17, Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP mice exhibited, as expected, conduction defects, characterized by prolonged QRS durations with R notches (R’) in ECG and abnormal activation patterns with right bundle branch (RBB) block in optical mapping (Fig. 2a,b). Importantly, these cardiac conduction defects in Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP mice are remarkably similar to those seen in Irx3−/− mice, which have only ~2-fold reduction in Cx40. On the other hand, the morphology of the VCS in Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP mice was indistinguishable from wild-type mice with well-formed bundle branches and distal fibers (Fig. 2c,d). These data support the conclusion that the conduction defects seen in Irx3−/− mice are not solely related to reduced Cx40 expression but arise, at least in part, from simultaneous structural changes in the VCS.

Figure 2. Loss of Cx40 results in abnormal electrical activation of the ventricles without morphological defects of the VCS.

(a) Representative surface ECG trace shows QRS prolongation and notched R’ wave in Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP mice. (b) Optical mapping in Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP heart exhibited RBB block, similar to Irx3−/− heart. (c,d) VCS structures visualized by Cx40-EGFP in both LV (c) and RSW (d) are normal in Irx3+/+;Cx40EGFP/EGFP mice. LV, left ventricle; RSW, right ventricular septal wall; HB, his-bundle; RBB, right bundle branch.

Irx3 is required for normal function of the VCS during postnatal development

Irx genes play key regulatory roles during embryonic development, including patterning, specification, and differentiation of various tissues and organs13,18,19. To determine the time course of the VCS morphological defects in Irx3−/− hearts, we first examined mutant hearts at embryonic day 15.5 (E15.5) and found no differences between Irx3−/− and Irx3+/+ control hearts (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, as seen both in postnatal day 5 (P5) and in adult (10–12 week old) Irx3−/− hearts14, Cx43 expression was ectopically expressed in the proximal bundle branches in Irx3−/− hearts at E15.5, which is a developmental stage when Cx43 is normally expressed in myocardium but not in the VCS bundle branches5,20 (Supplementary Fig. 4). These results are consistent with the conclusion that the regulation of gap junction channel expression in the VCS by Irx3 begins relatively early in embryonic development and continues into adulthood.

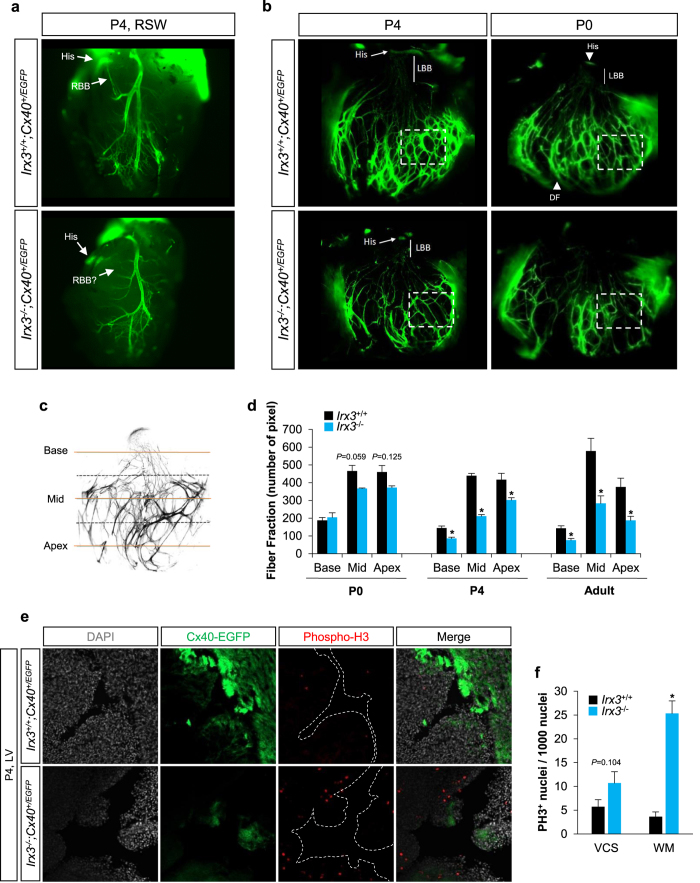

Given the fact that Nkx2.5 regulates early postnatal maturation of VCS12 and that Nkx2.5 physically interacts with Irx314, we next investigated the VCS structure of Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice during the early postnatal period. At postnatal day 4 (P4), consistent with adult hearts, RBB was often absent in Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice, but not in Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP mice (Fig. 3a), in association with marked reductions in VCS density and thinner EGFP-positive fibers, particularly in the distal Purkinje fibers (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, at P0, only mild morphological defects were observed in Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts compared with control mice. These findings suggest that loss of Irx3 impacts on the postnatal development of the VCS. Consistent with this suggestion, quantification of the number of VCS fibers at three different levels (i.e. base, mid, and apex) revealed that Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts exhibit only mild (~20%), but not significant, reductions in the number of fibers located in distal (i.e. mid and apex) VCS at P0, whereas by P4 (and thereafter) profound reductions (~50%; P < 0.02) in fiber numbers were observed throughout the VCS of Irx3−/− hearts (Fig. 3c,d). Thus, VCS morphology appears to rapidly deteriorate beginning at birth in the absence of Irx3.

Figure 3. Irx3 is required for postnatal formation of the VCS.

(a) Representative images of right bundle branch (RBB) in Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice at postnatal day 4 (P4). Note that RBB is absent in many cases when Irx3 is lost. (b) Representative images of the VCS in left ventricle of Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mice at P4 and P0. Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP mouse heart exhibit progressive deterioration of the VCS, characterized by reduced fiber density and thickness, compared to P0 heart which show only a mild structural defect. (c) A schematic diagram illustrates three different levels of the VCS (i.e. base, mid and apex) for analyzing VCS morphology by counting the number of fiber fraction. (d) Quantification of fiber fraction at three levels of the VCS (i.e. base, mid and apex) in three different developmental stages (i.e. P0, P4 and adult). (P0, Irx3+/+/Irx3−/−, n = 5/3; P4, Irx3+/+/Irx3−/−, n = 3/4; and adult, Irx3+/+/Irx3−/−, n = 6/4) *P < 0.05 vs. Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP. (e) Representative phospho-histone H3 (PH3) immunofluorescence in the left ventricle of P4 Irx3 mutant mouse heart expressing Cx40-EGFP that marks the VCS cells. (f) Quantification of PH3-positive cells revealed significantly higher number of proliferating cells in Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts, mainly in EGFP-negative myocardium, compared to Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP hearts. n = 4. *P < 0.05 vs. Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP hearts.

To determine whether this swift degradation of the VCS during the early postnatal period is caused by cell death or abnormal development, we measured cell apoptosis and proliferation in P4 Irx3 mutant mouse hearts containing the Cx40-EGFP transgenic reporter. Consistent with the above observations, smaller EGFP-positive populations (i.e. the VCS) and weaker EGFP intensity were found in Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts than Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP hearts (Fig. 3e). However, the number of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells were very low (less than 1 in 2500 cells) and indistinguishable between Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts (Supplementary Fig. 5). On the other hand, the proliferation rate estimated by the total number of cells with phospho-histone H3 (PH3) expression was noticeably elevated in Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP hearts compared to WT controls (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 6). Specifically, the number of PH3-positive cells increased (P < 0.001) in the EGFP-negative populations (i.e. working myocardium; WM) of Irx3−/− hearts when compared to the EGFP-positive populations (P = 0.104) (Fig. 3f). These data suggest that loss of Irx3 leads to increased proliferation, which might disturb the cell cycle exit required for recruitment and differentiation of ventricular cardiomyocytes into mature VCS cells.

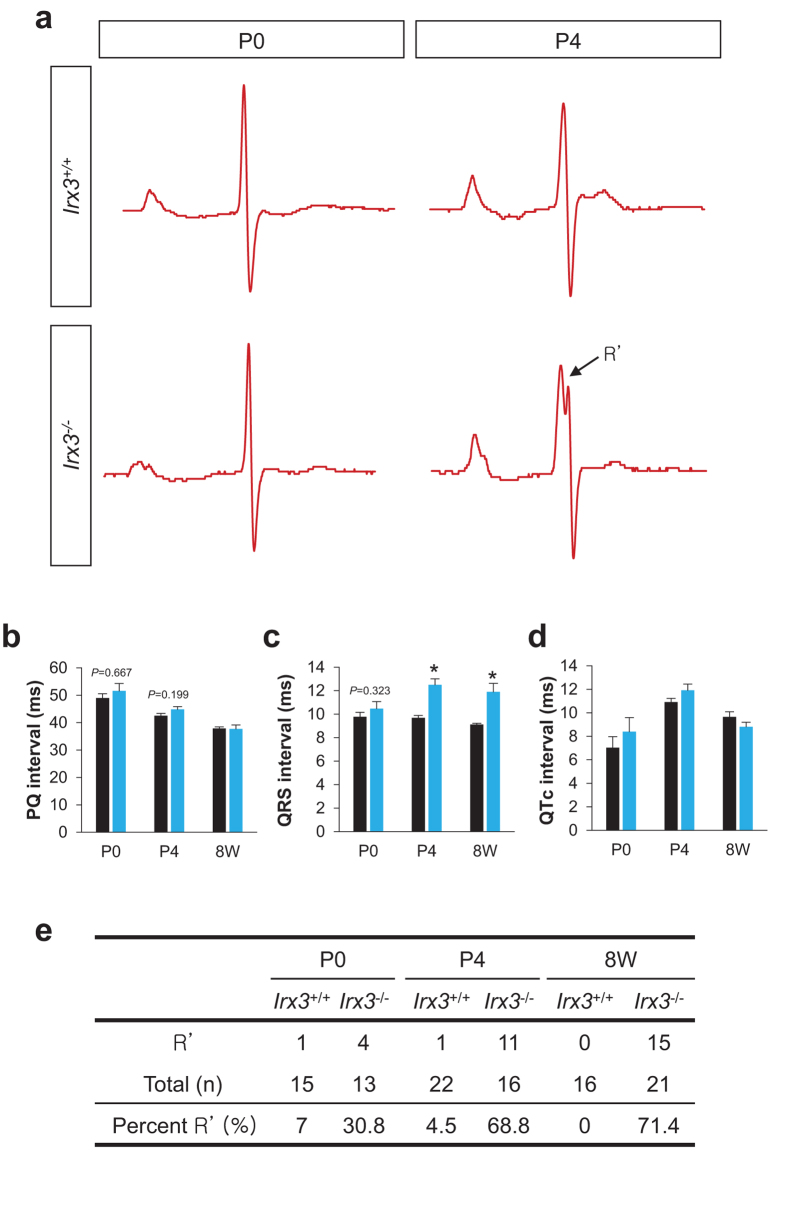

Next, we examined whether changes in the VCS structure were accompanied by electrophysiological changes. Surface ECG measurements revealed that PQ intervals, which progressively shorten with aging in both groups of mice, are not significantly different between Irx3+/+ and Irx3−/− mice (Fig. 4a,b) at any time point (P0, P4, and 8 weeks old (8 W)). QRS durations, which reflect the time for activation of ventricles, are not different (P = 0.323) between Irx3−/− mice (10.3 ± 0.5 ms) and WT littermate controls (9.7 ± 0.3 ms) at P0 (Fig. 4c), but are prolonged (P < 0.001) at P4 in the Irx3−/− mice (12.4 ± 0.4 ms) compared to Irx3+/+ mice (9.8 ± 0.2 ms), which are similar to that in 8 week old adult Irx3−/− mice (11.9 ± 0.7 ms). By contrast, QTc intervals are indistinguishable between Irx3+/+ and Irx3−/− mice at all ages tested (Fig. 4d). Importantly, notching of R-waves, an indicator of RBBB, was rarely observed in WT controls, but was seen in 31% (4/13) at P0 and rose to 69% (11/16) by P4 in Irx3−/− mice which is similar to the prevalence seen in adult Irx3−/− mice (71.4%, 15/21) (Fig. 4e). These results establish that the electrophysiological changes in Irx3−/− mice are accompanied by rapid progressive deterioration of VCS structure during the early postnatal period (within the first week after birth) and Irx3 is involved in early postnatal maturation of the VCS. Since the effects of Irx3 ablation on the expression of Cx40 and Cx43 are first detected relatively early in the developmental period compared to the postnatal structural deterioration, the requirement of Irx3 on gap junction expression appears temporally separated from that on the formation of the VCS structure.

Figure 4. Postnatal electrophysiological defects in Irx3−/− mice.

(a) Representative ECG traces of Irx3+/+ and Irx3−/− mice at P0 and P4. Analysis of neonatal mouse ECGs revealed that there are no differences in PQ (b) and QTc (d) intervals between Irx3+/+ and Irx3−/− mice all different developmental stages (i.e. P0, P4 and 8 week old (8 W)). On the other hand, QRS intervals of Irx3−/− mice, (c) that were not significantly different at P0 compared to controls, became prolonged from P4 onwards. (e) The prevalence of notched R’ wave, an indicator of right bundle branch block. *P < 0.05 vs. Irx3+/+ mice.

Molecular and functional associations of Irx3 with Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 in the heart

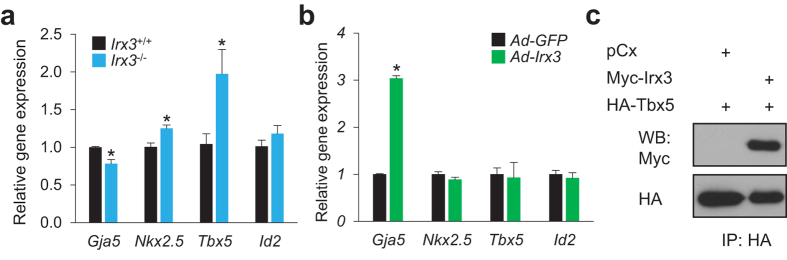

Previous studies have established that Irx3 expression overlaps with the expression of the Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Id2 transcription factors in the VCS, and that deficiencies of these transcription factors in mice (i.e. Nkx2.5+/−, Tbx5+/−, or Id2−/−) develop ventricular conduction defects with hypoplastic VCS morphology, widen QRS complex and/or reduced Cx40 expression8, which are remarkably similar to phenotypes observed in Irx3−/− mice. It seems plausible that the overlapping phenotypes among these different mouse models may arise from genetic or protein-protein interactions. Since gene dosage of Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 are clearly critical for VCS morphology8, we performed gene expression analysis in micro-dissected left ventricular endomyocardium at P4. Cx40 (Gja5) gene expression is significantly reduced in P4 Irx3−/− heart (Fig. 5a), as seen in adult Irx3−/− heart14. On the other hand, we unexpectedly observed that Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 expression is up-regulated (P = 0.007 and 0.029, respectively) in the early postnatal period in the Irx3−/− hearts compared to wild-type, which suggests that the VCS defects in Irx3−/− heart do not result from reduced gene dosage of Nkx2.5 or Tbx5. To examine further whether Irx3 directly regulates the expression of these cardiac TFs, Irx3 was overexpressed in cultured neonatal mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes (NMVM), using adenoviruses. However, though Irx3 overexpression led to elevated Cx40 gene (Gja5) expression, it did not alter the expression of Nkx2.5, Tbx5 or Id2 in the cultured cardiomyocytes (Fig. 5b), suggesting that elevations in Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 in P4 Irx3−/− heart might represent a compensatory response. An alternative conceivable explanation for the common phenotypes seen in mice lacking Irx3 and those heterozygous for Nkx2–5 or Tbx5 is that these transcription factors might interact directly in regulating VCS development. Indeed, we found that Irx3 and Tbx5 interact (Fig. 5c), as do Irx3 and Nkx2.5, which we showed previously14. These observations are consistent with the possibility that Irx3 interacts with Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 in a transcriptional complex that regulates the expression of genes required for VCS development and function.

Figure 5. Irx3 physically interacts with Tbx5.

(a) Gene expression analysis showed a reduction in Cx40 (Gja5) expression, but increases in Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 expression in P4 Irx3−/− endomyocardium compared to controls. n = 5 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. Irx3+/+ heart. (b) Adenovirus-mediated Irx3 overexpression (Ad-Irx3) in cultured neonatal ventricular myocytes resulted in elevated Cx40 expression, but no changes in Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Id2 expression, compared to control cells infected with GFP-expressing adenovirus (Ad-GFP). n = 3 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-GFP. (c) Co-immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated a direct physical interaction of Irx3 with Tbx5.

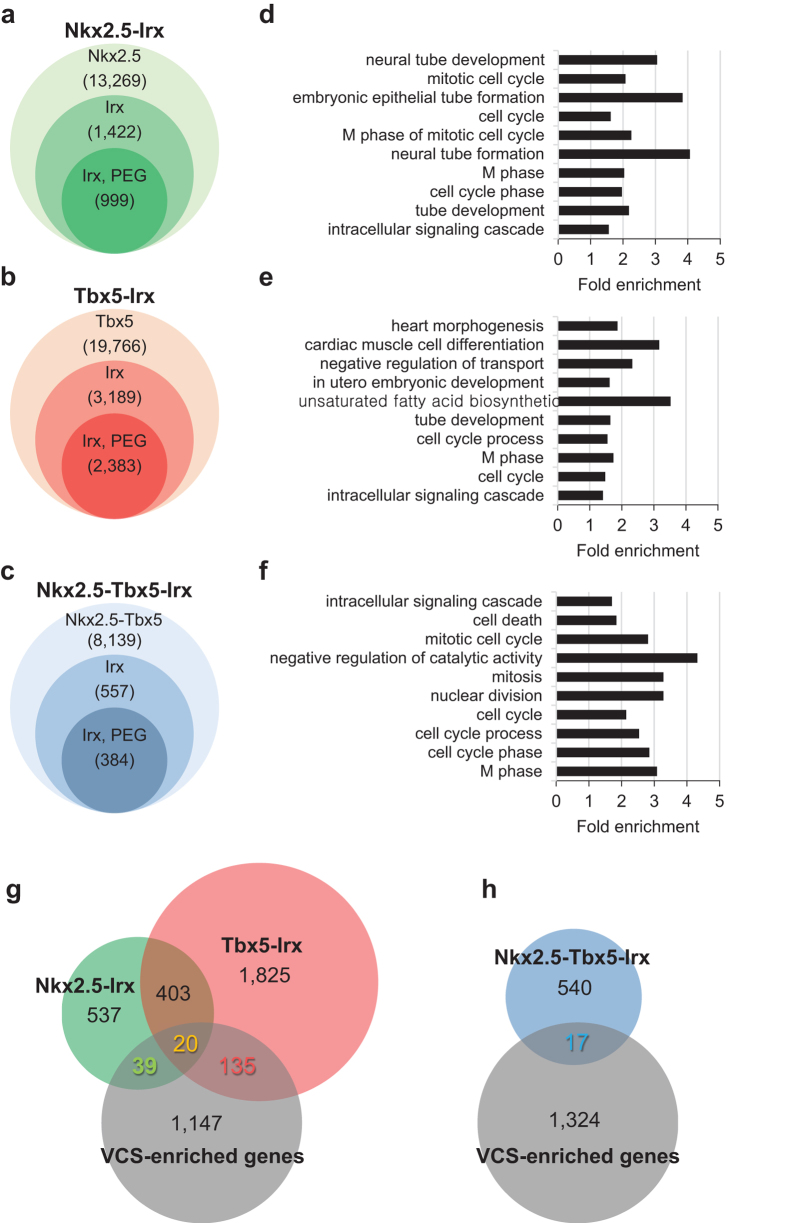

In order to test whether Irx3 works together with Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 in the regulation of gene expression, we first performed genome-wide in silico analysis to identify their target genes by using available ChIP-seq datasets combined with motif-based sequence analysis with the MEME suite21 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Specifically, from the ChIP-seq peak analysis of biotinylated Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 in HL-1 cardiac cell line22, we identified 13,269 and 19,766 genes containing Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 binding, respectively, within +/−50 kb of the transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 6a,b). Next, to predict Irx3 target genes, we used the FIMO (find individual motif occurrence) program to scan genome-wide sequences with two putative Irx motif sequences, ‘ACATGT’23 and ‘ACAnnTGT’24 (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Analysis to assess the distribution of Irx motif sequences relative to Nkx2.5 or Tbx5 ChIP-seq peaks showed that Irx motifs were mainly enriched within 1000 bp of the Nkx2.5 or Tbx5 peaks (Supplementary Fig. 8), consistent with the hypothesis that Irx3 works closely with Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 during transcriptional regulation. As the distribution of distances between Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 peaks showed a peak at about 500 bp, we then applied more stringent criteria of selecting genes containing Irx motifs within 500 bp from either Nkx2.5 or Tbx5 peaks, identifying 1,422 genes for Nkx2.5-Irx and 3,189 genes for Tbx5-Irx co-occurrence (Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary dataset). We also examined the possible common targets of three transcription factors, and identified 557 genes as Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx co-occurrence among 8,139 genes containing both Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 peaks within 500 bp (Fig. 6c). To interpret Nkx2.5-Irx,Tbx5-Irx, or Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx downstream targets in biological process, we performed gene ontology (GO) term analysis only for protein encoding genes (PEG), which are 999, 2,383, and 384 genes for Nkx2.5-Irx, Tbx5-Irx, and Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx, respectively (Fig. 6d,e,f, and Supplementary dataset). Interestingly, cell cycle related functions were the top enriched GO terms in all Nkx2.5-Irx, Tbx5-Irx and Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx candidate genes.

Figure 6. In silico analysis identifies Nkx2.5, Tbx5, and Irx3 target genes.

(a–c) Venn diagrams showing the number of genes with ChIP-seq peaks, Irx motifs, and protein encoding genes (PEG) for Nkx2.5 (a), Tbx5 (b), and Nkx2.5-Tbx5 (c). (d–f) Selected GO terms associated with biological process for Nkx2.5-Irx (d) Tbx5-Irx (e) and Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx (f) genes (for complete data set, see Supplemental Dataset). (g–h) Venn diagrams showing the overlap and distribution of Nkx2.5-Irx (green) & Tbx5-Irx genes (red), as well as Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx genes (yellow or blue) in comparison with VCS-enriched genes.

To further narrow down and identify Nkx2.5-Irx3, Tbx5-Irx3 and Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx3 target genes, which are preferentially expressed in the VCS, we scanned the VCS-enriched genes (≥1.5 fold change in PF vs. WM) identified from microarray experiments using sorted cardiomyocytes isolated from adult Contactin-2-EGFP;αMHC-Cre;R26tdTomato/+ reporter mice25 (Supplementary dataset). This comparison revealed that 59 (green) and 155 (red) target genes of Nkx2.5-Irx and Tbx5-Irx groups, respectively, are enriched in the VCS (Fig. 6g). Among them, 20 genes (yellow) overlap in both Nkx2.5-Irx and Tbx5-Irx, consistent with previous studies that Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 cooperate in the VCS development8. More importantly, the comparison between VCS-enriched genes and 384 Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx target genes led to identification of 17 genes (blue), which are all found in the “overlapping” genes between Nkx2.5-Irx-PF and Tbx5-Irx-PF groups (Fig. 6h and Supplementary dataset). This result supports the possibility that Irx3 forms a transcription complex with Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 together.

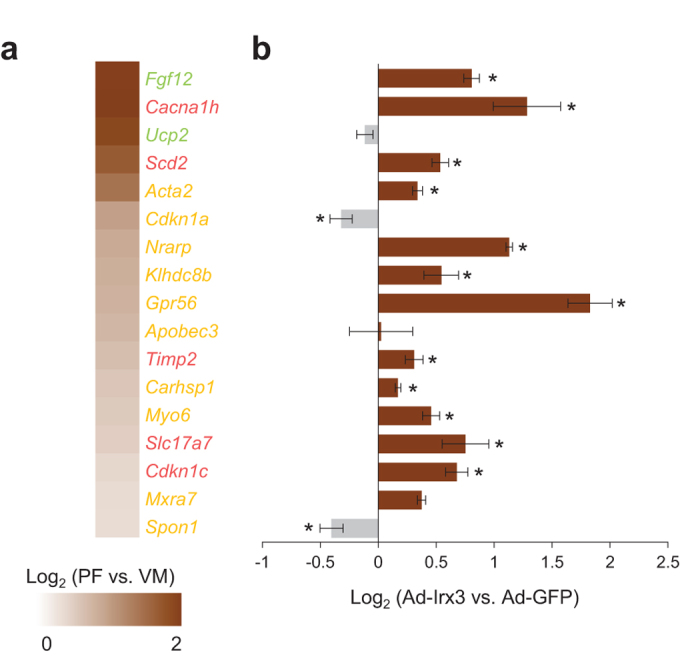

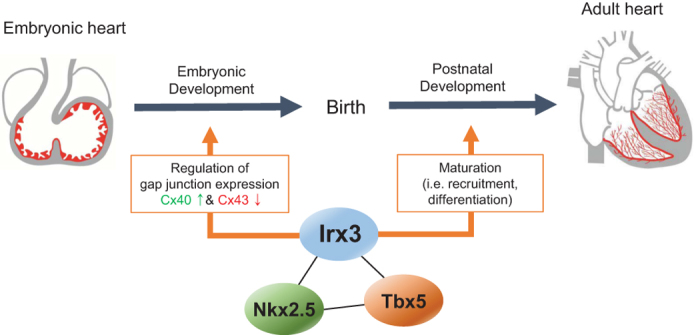

To functionally validate whether these predicted target genes are regulated by Irx3, we tested top 10 candidate genes out of 17 VCS-enriched Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx genes, as well as several top candidate genes (≥2 fold change in VCS vs. WM) from Nkx2.5-Irx-PF and Tbx5-Irx-PF gene lists, such as Fgf12, Ucp2, Cacna1h, Scd2, Timp2, Slc17a7, and Cdkn1c (Fig. 7a). qPCR analysis in NMVM overexpressing Irx3 showed that Irx3 promotes significant upregulation in most of candidate genes, including Fgf12, Cacna1h, Nrarp, Gpr56, Myo6, Slc17a7, Cdkn1c and Mxra7 (Fig. 7b). Thus, our in silico analysis coupled with functional verification suggests that Irx3 acts as a co-factor of Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 in transcriptional regulation of VCS genes. Taken together, our current and previous studies14 suggest a model wherein Irx3 interacts with Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 in a transcriptional complex required for proper development and function of the VCS (Fig. 8), and loss of Irx3 might lead to disrupted Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 transcriptional complexes resulting in VCS abnormalities seen similarly in Nkx2.5 or Tbx5 mutant mice.

Figure 7. Irx3 promotes expression of VCS-enriched Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 target genes.

(a) Expression of selected VCS-enriched genes, shown as the log2 expression ratio between Purkinje fibers (PF) and working myocardium (WM). Gene are color-coded for Nkx2-5-Irx-VCS (green), Tbx5-Irx-VCS (red), and Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx-VCS (yellow). (b) qPCR experiment demonstrates that Irx3 activates most of VCS-enriched genes in cardiomyocytes, shown as the log2 expression ratio between Ad-Irx3 and Ad-GFP. n = 3–5 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-GFP.

Figure 8. Irx3 is essential for VCS development and function.

A schematic model of Irx3 cooperating with Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 in the VCS development and function.

Discussion

We previously showed that loss of Irx3 is associated with impaired conduction in the VCS, such as slowed ventricular activation and RBB block14. These studies further revealed that Irx3 ablation leads to reduced Cx40 expression in the VCS combined with ectopic Cx43 expression in the proximal bundle branches, consistent with molecular studies establishing that Irx3 antithetically regulates the gap junction genes, Cx40 (Gja5) and Cx43 (Gja1), in the VCS14. However, several observations suggest that the electrical changes in Irx3−/− mice could also involve other factors as well. For example, although Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3−/− mice show similar (~2-fold) reductions in Cx4018, Cx40 heterozygous mutant mice do not show overt cardiac conduction defects, which suggest that Irx3 may also have other effects on the VCS, in addition to its actions on gap junction expression. Accordingly, in this study we demonstrate that Irx3 plays an essential role in maintaining the structural integrity of the VCS in the postnatal period. Specifically, loss of Irx3 results in progressive deterioration of the His-Purkinje system, which begins at birth. The profound reductions in the fiber density are expected to impair cardiac electrical activation leading to widening of the QRS interval and the RBB block that are seen in Irx3−/− mice. The appearance of RBB block, without evidence for LBB block, is not unexpected due to the dramatic differences in the structures of the right and left bundle branches. Specifically, the left bundle branches have an abundance of fascicles compared to the right bundle branches which often has only one or two strand in both mice and human16,26. As a consequence of reductions in the right and left bundle branches arising with the loss of Irx3, we often observed the absence of right bundle branches, which would explain the appearance of RBB block.

It is worth mentioning that the structural defects of the VCS and altered gap junction expression in Irx3−/− heart appear to be temporally discordant, suggesting that they may not be inter-dependent. First, at E15.5, when the Cx40 and Cx43 expression has already restricted to the VCS and the working myocardium5,20, respectively, Irx3−/− hearts show a normal morphology of fiber structure, despite ectopic expression of Cx43. Second, mice lacking Cx40, which show almost identical electrophysiological defects to Irx3−/− mice, have normal structure of VCS. Third, morphological defects in Irx3−/− VCS are found prominently in regions where Cx43 is not ectopically expressed (i.e. distal Purkinje fibers). Nevertheless, there is a possibility that ectopic Cx43 expression and reduced Cx40 expression Irx3−/− embryonic hearts, which are expected to functionally affect the embryonic heart pumping, can influence on postnatal maturation of the VCS structure, as previous studies show that hemodynamics can affect VCS development and maturation27,28.

Our results revealed that Irx3 is essential for postnatal development of the VCS, since the number and thickness of the His-Purkinje fiber network as well as the rate of ventricular activation (i.e. QRS intervals) are reduced progressively after birth. Previous studies suggest that VCS development can be largely divided into two temporal stages12. First, a prenatal VCS developmental process involves expansion of pre-specified conduction cells as well as recruitment and expansion of cells derived from the underlying trabeculae of the embryonic ventricle1. Then, during postnatal period, the VCS is further differentiated, resulting in the formation of the mature Purkinje fiber network. While no noticeable changes in VCS structure or trabecular layer were observed in embryonic Irx3−/− hearts at E15.5, there were elevated numbers of proliferating cells in postnatal Irx3−/− heart (i.e. P4). These findings indicate that postnatal VCS defects in Irx3−/− heart are probably not caused by abnormal trabeculation during embryonic development, but by a postnatal maturation defect, possibly due to delay cell cycle exit after birth. Indeed, increased proliferation was seen in surrounding (i.e. Cx40-negative) working myocardium of Irx3−/− heart without changes in apoptotic death of VCS cells. These are further supported by our computational analysis showing that predicted Nkx2.5-Irx, Tbx5-Irx and Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx target genes are enriched for cell cycle-associated function as well as by the functional verification showing that Irx3 altered transcript levels of Cdkn1a and Cdkn1c, which encode cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p57, respectively, yet how these function during VCS development and maturation remains to be explored. In addition, it has been recently reported that Drosophila Iroquois proteins restrict cell cycle progression via non-transcriptional mechanism with a physical interaction with Cyclin E-containing protein complexes29. Together, ours and other studies suggest a possibility that Irx3 controls cell cycle, thereby regulating postnatal recruitment and differentiation into mature VCS cells from progenitor cells residing in working myocardium. Previous studies have demonstrated that expansion and recruitment of VCS cells from nearby working ventricular cardiomyocytes are positively affected by endothelin-130,31 and neuregulin-132 during embryonic heart development. Therefore, it will be interesting to determine the mechanism by which Irx3-expressing VCS cells regulates the recruitment and differentiation of Irx3-negative working myocardium into mature VCS cells during postnatal development.

It is notable that the hypoplastic VCS defects observed in Irx3−/− mice are remarkably similar to those seen in mice with haploinsufficiency of Nkx2–54,12 and Tbx57. Indeed, our results showing a direct interaction of Irx3 with Tbx5 as well as Nkx2.5 strongly support a model that a transcriptional complex of these factors is critical for development and maintenance of the VCS structure and function. This model is supported by bioinformatic predictions followed by the functional verification demonstrating that Irx3 functions as a transcriptional regulator on the genes to which Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 bind.

While our in silico analysis combined with qPCR verification using Irx3-overexpressed cardiomyocytes identified candidate target genes of Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Irx3, there is still limitation to conclude whether this is through direct or indirect regulation, due to complexity of gene regulation. For example, it was unexpected that Cx40 gene, Gja5, which we and other have demonstrated that Irx3 positively regulates its expression14,15, was not found via our bioinformatics approaches. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 9a, Gja5 contains co-occurrence of Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 ChIP-seq peaks as well as Irx motif which is located about 1 kb away (that is why our stringent method eliminated Gja5 from the candidate list), yet these peaks and motifs are all found, not in the promoter region, but at around 10 kb away from the transcriptional end site. In addition, we found that, in most of top candidate genes, Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 ChIP-seq peaks with Irx motif were found in downstream of the TSS (i.e. intron) or extragenic region (Supplementary Fig. 9b and Supplementary dataset). As discussed previously33, our observations suggest that Irx3 may be involved in complex transcriptional regulation via genetic elements such as enhancer. Therefore, in order to further decipher the mechanistic details of transcriptional regulation by Irx3, Nkx2.5 and Tbx5, additional experiments using various techniques, such as ChIP-seq for Irx3 and other epigenetic marks, chromosome conformation capture, a reporter assay will be necessary. Also, as Irx3 has dual functions depending on developmental stages, it would be of interest to delineate embryonic and postnatal transcriptional regulatory networks within VCS. Interestingly, most of 17 candidate target genes of Nkx2.5-Tbx5-Irx3 from the bioinformatics analysis have not been previously associated with the VCS or even with cardiovascular system, as summarized in Supplementary dataset. Therefore, future studies are warranted to examine whether/how these genes contribute to VCS development and function.

Together, in addition to our previous findings14, this study revealed a novel role for Irx3 in the morphological development of the VCS, demonstrating that Irx3 is a conductor of ventricular conduction system34 by maintaining the integrity of VCS structure and function. As mutations in NKX2-535,36,37 and TBX538,39,40 are found in patients with conduction defects, a recent study has identified two novel IRX3 mutations, R421P and P485T, in idiopathic VF patients without other genetic defects in well-known arrhythmogenic genes15. In vitro experiments also showed that mutated forms of IRX3 led to reduced transcriptional regulation compared to wild-type IRX3, suggesting that these mutant IRX3 alleles associated with arrhythmia act as hypomorphic or loss-of-function mutations. Therefore, as anatomy and development of the VCS is well conserved between mouse and human, our findings here would provide additional insight and mechanism for conduction defects associated with IRX3 mutations.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by The Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy Animal Care Committee, University of Toronto as well as by The Toronto Centre for Phenogenomics Animal Care Committee (ACC), and conformed to the standards of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. All mice were housed in standard vented cages in temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms with 12-hour light-dark cycles. Irx3+/− and Irx3+/LacZ mice were previously described14, and were maintained in the CD1 background. Neonatal and adult Irx3 mice were generated by intercrossing Irx3+/− mice. In order to visualize the VCS, Irx3+/− mice were crossed with Cx40+/EGFP knock-in reporter mice that express GFP under the control of the Gja5 (Cx40) promoter16 (courtesy of Dr. Lucile Miquerol). For comparison of VCS morphology using β-galactosidase staining, Irx3+/LacZ mice were intercrossed with Irx3+/− mice to generate Irx3+/LacZ and Irx3−/LacZ mice, which allow us to properly compare control (i.e. heterozygous) and knock-out mouse hearts under single copy of LacZ gene.

ECG measurements

Mice were anesthetized using a mixture of isoflourane and oxygen. Anesthetized mice were secured in a supine position on a regulated heat pad while lead I and lead II ECGs were recorded using platinum subdermal needle electrodes in a 3-limb configuration. Core temperature was continuously monitored using a rectal probe and maintained at 36–37 °C. ECG data was acquired and analyzed using PONEMAH Physiology Platform P3 Plus software and an ACQ-7700 acquisition interface unit (Gould Instruments, Valley View, OH, USA). The parameters derived from the ECG measurements include: Heart rate (HR), PR interval (beginning of P wave to the beginning of the QRS complex), QRS complex duration, and QT interval (beginning of Q wave to end of T wave).

Optical mapping and analysis

Mice were heparinized (0.2 ml intraperitoneal injection (I.P.) of 1000 IU/ml heparin) to prevent blood clotting and were sacrificed under isofluorane via cervical dislocation. The thorax was opened by midsternal incision, and the beating heart was rapidly removed and placed in cold Krebs solution consisting of (in mmol/L) 118 NaCl, 4.2 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 11 D-Glucose, 2 Sodium Pyruvate, and 25 NaHCO3, with pH adjusted to 7.4 via bubbling with carbogen (95% CO2/5% O2). The heart was then rapidly transferred to the bath of a modified horizontal Langendorff in cold Krebs solution where the aorta was cannulated onto a blunted 20-gauge needle attached to a bubble trap and a water jacket-heated perfusion system to allow for retrograde perfusion of the coronary arteries while enabling the rotation of the heart about its vertical axis. Once mounted, the heart was perfused with Krebs solution at a constant flow rate of 3.5 ml/min, for a 15 minute equilibration period followed by 10 minute of voltage sensitive dye, di-4-ANEPPS, perfusion and wash. A concentration of 0.1 μM ATP dependent K+ channel opener, P1075, was added to the perfusing Krebs solution in order to offset the coronary constriction and rise in aortic pressure observed during dye administration41,42. Perfusion rates were maintained such that a coronary pressure of 70–90 mmHg was observed during measurements. Perfusion temperature was monitored and held at 36–37 °C throughout the experiment. All mapping studies were performed in the absence of any motion reduction techniques.

Ventricular conduction system morphology: Fiber imaging, quantification of EGFP fluorescence, and measurement of fiber fraction

Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP adult (10–12 week old), P4 and P0 mice were anaesthetized and sacrificed via cervical dislocation. The hearts were rapidly excised and placed in room temperature standard PBS solution (pH 7.4). For imaging left ventricular conduction system, LV wall was carefully cut open at the centre of the free wall in adult, P4 and P0 mouse hearts, while making sure no major arteries or conduction fibers were damaged. The heart was pinned down and occasionally flattened with a glass slide to maximize the number of fibers in focus. Images of the hearts were taken using an upright Olympus MVX-10 microscope equipped with a CoolSnap HQ (Photometrics, Surrey, BC) camera interfaced with ImagePro Plus 5.1 software. Irx3 deficient, heterozygous and wild-type mice with the Cx40-EGFP reporter were excited (EXFO X-Cute exacte). For comparison purposes, littermates were images on the same day at comparable magnification, exposure and light intensity. Cx40 promoter-dependent GFP expression was determined by measuring the intensity of EGFP fluorescence in the LBB and distal Purkinje fibers of Irx3−/−;Cx40+/EGFP, Irx3+/−;Cx40+/EGFP and Irx3+/+;Cx40+/EGFP mice. For control purposes, EGFP fluorescence intensity was also measured in the atria and septal artery of all three mouse groups, where Irx3 is not expressed. Intensity of fluorescence was measured using Image J software in multiple fibers divided by the fiber area and averaged to obtain a value for the LBB and Purkinje fibers. To examine thickness and numbers of the VCS, fiber fraction was measured in left ventricular VCS of wild-type and Irx3−/− heart with the background of Cx40-EGFP at P0 and P4. In brief, threshold was determined by measuring the level of background from 12 different regions containing myocardium without fiber using Image J. The left ventricular conduction system of all hearts was divided into 3 sections from the His bundle to the end of the distal Purkinje fibers (marked by dashed lines in Fig. 3c). Then, the number of pixels above threshold (>0; signifying pixels that account for fibers) along the three lines was counted.

LacZ staining

Irx3+/LacZ and Irx3−/LacZ hearts were dissected in cold PBS, and fixed in 1% formaldehyde, 0.02% NP-40 in PBS. After fixation, hearts were washed in 2 mM MgCl2, 0.02% NP-40 in PBS at 4 °C for four times for 15 minutes each. For embryonic VCS examination, dissected E15.5 embryos were immediately frozen in OCT on dry ice. After cryo-sections taken at 25 μm, sections were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS on ice for 10 minutes, and washed in detergent rinse for 10 min. For β-gal staining, hearts or slides were incubated in X-gal or Bluo-gal solution containing 1 mg/ml X-gal or Bluo-gal, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.02% NP-40, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6-3 H2O, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6 in PBS at 37 °C overnight. Following incubation, hearts or slides were fixed in 4% formaldehyde. Sections were further counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Labs) for 1 minute and mounted with VectaMount AQ (Vector Labs).

Immunofluorescent staining

P4 heart and E15.5 embryos were cut into 15–20 μm thick sections with a cryo stat. Sections were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 5 minutes, blocked with 5% normal donkey serum diluted in PBST for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. After rinsing 3 times for 5 minutes with PBS, proper secondary antibodies (1:500) were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then rinsed 3 times with PBS and then mounted with DAPI-containing mounting medium (Vector Labs). The following primary antibodies were sued: anti-phosphor-histone H3 (rabbit, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-cleaved caspase 3 (rabbit, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Cx40 (goat, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-Cx43 (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signaling Technology).

Co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Co-immunoprecipitation was conducted in COS-7 cells 48 hours after transfection with PCx, Myc-Irx3, and HA-Tbx5 constructs, as previously described14. After incubation with the indicated antibodies overnight at 4 °C, immunoprecipitates were pulled down with protein G–Sepharose beads and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies overnight at 4 °C, following standard protocols.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from micro-dissected endomyocardium at P4 or cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes isolated43 and infected with adenovirus expressing GFP or Irx3, using TRIzol (Life Technologies), and then cDNA was synthesized with MMLV-RT (Life Technologies). Quantitative PCR was performed with Power SYBR green enzyme on Viia7 (Life Technologies), and ∆∆CT normalized with Actb or Tbp expression were used for relative comparison. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Computational analysis and prediction of Irx3, Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 target genes

Two putative Irx motif sequences (Supplementary Fig. 7b), derived from ‘ACATGT’23 and ‘ACAnnTGT’24, and MotifMap database44, were used for predicting genome-wide Irx3 motif occurrences. This was accomplished following a whole genome search of the putative motifs on mouse genome assembly GRCm38 sequence using FIMO (Find Individual Motif Occurrences), part of the MEME software package (http://tools.genouest.org/tools/meme/)45. Only motif occurrences with p-values less than or equal to 1.0 × 10−5 were considered. P-values are calculated by FIMO program and are based on a log-likelihood ratio score conversion. For more details of FIMO program calculations please refer to46.

To identify downstream genes of Nkx2.5, Tbx5 and Irx3 in the heart, we used previously described parameters for cardiac transcription factor binding sites proximity22 to define co-occurrence of either Nkx2.5 or Tbx5 peaks with Irx motifs near gene loci. Previously identified enriched Chromatin Immuno-precipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) peak files for Nkx2.5 (GSM558906) and Tbx5 (GSM558908) (GEO accession # GSE21529) were downloaded in GFF format (as mm9 assembly coordinates). Their genomic coordinates were converted to GRCm38 sequence assembly coordinates using LiftOver tool (https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgLiftOver) for co-occurrence analysis. Briefly, we first determined potential target genes by mapping Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 enriched peaks to the nearest genes within +/−50 kb of transcriptional start sites (TSS) as defined by Ensembl GRCm38 gene annotations. Gene loci associated with either Nkx2.5 or Tbx5 were then further examined for the presence of Irx motifs that are 500 bp or less away from Nkx2.5 and/or Tbx5 peaks. The DAVID software was used for Gene Ontology analysis on protein coding genes.

We further narrowed down the list of predicted target genes with regards to the VCS by comparing with VCS-enriched genes. List of VCS-enriched genes were obtained using the microarray dataset (GSE60987) that was performed in two populations of sorted cardiomyocytes (PF: Tomato+EGFP+ vs. WM: Tomato+EGFP−) isolated from the ventricles of adult compound transgenic mice expressing PF (Cntn2-EGFP) and cardiomyocyte specific (α-MHC–Cre;R26tdTomato/+) reporter genes25. Microarray data analysis was performed using Expression Console and Transcriptome Analysis Console software (Affymetrix) with criteria of ANOVA P-value < 0.05 and ≥1.5 fold changes.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (the standard error of the mean). Significance was determined by student t-test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Calculations and statistical test were performed using the Sigma Stat 3.0 program.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kim, K.-H. et al. Irx3 is required for postnatal maturation of the mouse ventricular conduction system. Sci. Rep. 6, 19197; doi: 10.1038/srep19197 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors thank to Dr. Lucile Miquerol for Cx40+/EGFP mice as well as Roozbeh Aschar-Sobbi, Joe Eun Son and Min Seon Choe for technical supports. This study was supported by grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to Drs. Chi-chung Hui and Peter H. Backx (MOP119339 and MOP43940). K.-H.K. was supported by fellowships from the Heart and Stroke Foundation Canada and the Hospital for Sick Children (Restracomp).

Footnotes

Author Contributions K.-H.K., A.R., C.-C.H. and P.H.B. designed the experiments. K.-H.K. and A.R. performed electrophysiological measurement, histological and morphological analyses, gene expression assay, cardiomyocyte culture and microarray analysis. S.M.I.H. and A.N. contributed to computational analysis for ChIP-seq peaks and motif-based sequence analysis. V.P. conducted co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. A.K. contributed to neonatal ECG measurement. C.C. contributed to sample collection and mouse colony management. K.-H.K., A.R., C.-C.H. and P.H.B. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

References

- Miquerol L., Beyer S. & Kelly R. G. Establishment of the mouse ventricular conduction system. Cardiovasc Res 91, 232–242, 10.1093/cvr/cvr069 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinman M. M. Role of the His-Purkinje system in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm 6, 1050–1058, 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.03.011 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs L. E. et al. Perinatal loss of Nkx2-5 results in rapid conduction and contraction defects. Circ Res 103, 580–590, 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171835 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay P. Y. et al. Nkx2-5 mutation causes anatomic hypoplasia of the cardiac conduction system. J Clin Invest 113, 1130–1137, 10.1172/JCI19846 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker M. L. et al. Transcription factor Tbx3 is required for the specification of the atrioventricular conduction system. Circ Res 102, 1340–1349, 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169565 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogaars W. M. et al. The transcriptional repressor Tbx3 delineates the developing central conduction system of the heart. Cardiovasc Res 62, 489–499, 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.030 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz I. P. et al. The T-Box transcription factor Tbx5 is required for the patterning and maturation of the murine cardiac conduction system. Development 131, 4107–4116, 10.1242/dev.01265 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz I. P. et al. A molecular pathway including Id2, Tbx5, and Nkx2-5 required for cardiac conduction system development. Cell 129, 1365–1376, 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.036 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Tran V. T. et al. A novel genetic pathway for sudden cardiac death via defects in the transition between ventricular and conduction system cell lineages. Cell 102, 671–682 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismat F. A. et al. Homeobox protein Hop functions in the adult cardiac conduction system. Circ Res 96, 898–903, 10.1161/01.RES.0000163108.47258.f3 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. et al. A mouse model of congenital heart disease: cardiac arrhythmias and atrial septal defect caused by haploinsufficiency of the cardiac transcription factor Csx/Nkx2.5. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 67, 317–325 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meysen S. et al. Nkx2.5 cell-autonomous gene function is required for the postnatal formation of the peripheral ventricular conduction system. Dev Biol 303, 740–753, 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.044 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. H., Rosen A., Bruneau B. G., Hui C. C. & Backx P. H. Iroquois homeodomain transcription factors in heart development and function. Circ Res 110, 1513–1524, 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265041 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. S. et al. Iroquois homeobox gene 3 establishes fast conduction in the cardiac His-Purkinje network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 13576–13581, 10.1073/pnas.1106911108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi A. et al. Genetic defects in a His-Purkinje system transcription factor, IRX3, cause lethal cardiac arrhythmias. Eur Heart J, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv449 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquerol L. et al. Architectural and functional asymmetry of the His-Purkinje system of the murine heart. Cardiovasc Res 63, 77–86, 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.03.007 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A. M., Goodenough D. A. & Paul D. L. Mice lacking connexin40 have cardiac conduction abnormalities characteristic of atrioventricular block and bundle branch block. Curr Biol 8, 295–298 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaborit N. et al. Cooperative and antagonistic roles for Irx3 and Irx5 in cardiac morphogenesis and postnatal physiology. Development 139, 4007–4019, 10.1242/dev.081703 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. et al. Formation of proximal and anterior limb skeleton requires early function of Irx3 and Irx5 and is negatively regulated by Shh signaling. Dev Cell 29, 233–240, 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco D. & Icardo J. M. Molecular characterization of the ventricular conduction system in the developing mouse heart: topographical correlation in normal and congenitally malformed hearts. Cardiovasc Res 49, 417–429 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machanick P. & Bailey T. L. MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics 27, 1696–1697, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr189 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A., Kong S. W., Ma Q. & Pu W. T. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 5632–5637, 10.1073/pnas.1016959108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M. F. et al. Variation in homeodomain DNA binding revealed by high-resolution analysis of sequence preferences. Cell 133, 1266–1276, 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.024 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilioni A., Craig G., Hill C. & McNeill H. Iroquois transcription factors recognize a unique motif to mediate transcriptional repression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 14671–14676, 10.1073/pnas.0502480102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. E. et al. PCP4 regulates Purkinje cell excitability and cardiac rhythmicity. J Clin Invest 124, 5027–5036, 10.1172/JCI77495 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen T. A. et al. Discontinuous conduction in mouse bundle branches is caused by bundle-branch architecture. Circulation 112, 2235–2244, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.547893 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. E. et al. Hemodynamic-dependent patterning of endothelin converting enzyme 1 expression and differentiation of impulse-conducting Purkinje fibers in the embryonic heart. Development 131, 581–592, 10.1242/dev.00947 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckova M. et al. Hemodynamics is a key epigenetic factor in development of the cardiac conduction system. Circ Res 93, 77–85, 10.1161/01.RES.0000079488.91342.B7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios N., Gonzalez-Perez E., Hernandez R. & Campuzano S. The Homeodomain Iroquois Proteins Control Cell Cycle Progression and Regulate the Size of Developmental Fields. PLoS Genet 11, e1005463, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005463 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikawa T. et al. Induction and patterning of the Purkinje fibre network. Novartis Found Symp 250, 142–153, discussion 153–146, 276–149 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi-Suzuki K., Yanagisawa M., Gourdie R. G., Kanzawa N. & Mikawa T. In vivo induction of cardiac Purkinje fiber differentiation by coexpression of preproendothelin-1 and endothelin converting enzyme-1. Development 127, 3523–3532 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentschler S. et al. Neuregulin-1 promotes formation of the murine cardiac conduction system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 10464–10469, 10.1073/pnas.162301699 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S., Romanoski C. E., Benner C. & Glass C. K. The selection and function of cell type-specific enhancers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16, 144–154, 10.1038/nrm3949 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. G. Irx3: a conductor of conduction. Circ Res 109, 984–985, 10.1161/RES.0b013e318237bf49 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D. W. et al. Mutations in the cardiac transcription factor NKX2.5 affect diverse cardiac developmental pathways. J Clin Invest 104, 1567–1573, 10.1172/JCI8154 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara H. et al. Loss of function and inhibitory effects of human CSX/NKX2.5 homeoprotein mutations associated with congenital heart disease. J Clin Invest 106, 299–308, 10.1172/JCI9860 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott J. J. et al. Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5. Science 281, 108–111 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson C. T. et al. Mutations in human TBX5 [corrected] cause limb and cardiac malformation in Holt-Oram syndrome. Nat Genet 15, 30–35, 10.1038/ng0197-30 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Y. et al. Holt-Oram syndrome is caused by mutations in TBX5, a member of the Brachyury (T) gene family. Nat Genet 15, 21–29, 10.1038/ng0197-21 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori A. D. & Bruneau B. G. TBX5 mutations and congenital heart disease: Holt-Oram syndrome revealed. Curr Opin Cardiol 19, 211–215 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova M. et al. Effects of voltage sensitive dye di-4-ANEPPS on guinea pig and rabbit myocardium. Gen Physiol Biophys 27, 45–54 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren A. et al. Voltage-sensitive dye mapping of activation and conduction in adult mouse hearts. Ann Biomed Eng 28, 958–967 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. H., Oudit G. Y. & Backx P. H. Erythropoietin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 324, 160–169, 10.1124/jpet.107.125773 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daily K., Patel V. R., Rigor P., Xie X. & Baldi P. MotifMap: integrative genome-wide maps of regulatory motif sites for model species. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 495, 10.1186/1471-2105-12-495 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Johnson J., Grant C. E. & Noble W. S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res 43, W39–49, 10.1093/nar/gkv416 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant C. E., Bailey T. L. & Noble W. S. FIMO: scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27, 1017–1018, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.