Abstract

Background

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline recommends use of a cystatin C-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) to confirm creatinine-based eGFR between 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2. Prior studies have demonstrated that comorbidities such as solid-organ transplant strongly influence the relationship between measured GFR, creatinine and cystatin C. Our objective was to evaluate the performance of cystatin C based eGFR equations compared to creatinine-based eGFR and measured GFR across different clinical presentations.

Methods

The performance of the CKD-EPI 2009 creatinine-based estimated GFR equation (eGFRCr) and the newer CKD-EPI 2012 cystatin C-based equations (eGFRCys and eGFRCr-Cys) were compared with measured GFR (iothalamate renal clearance) across defined patient populations. Patients (n = 1,652) were categorized as transplant recipients (n=568 kidney; n=319 other organ [non-kidney]), known chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients (n=618), or potential kidney donors (n=147).

Results

eGFRCr-Cys showed the most consistent performance across different clinical populations. Among potential kidney donors without CKD (stage 2 or higher; eGFR >60mL/min/1.73m2), eGFRCys and eGFRCr-Cys demonstrated significantly less bias than eGFRCr, however, all three equations substantially underestimated GFR when eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73m2. Among transplant recipients with CKD stage 3B or lower (eGFR <45mL/min/1.73m2), eGFRCys was significantly more biased than eGFRCr. No clear differences among eGFR bias between equations were observed among known CKD patients regardless of eGFR range, or in any patient group with a GFR between 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2.

Conclusions

The performance of eGFR equations depends on patient characteristics readily apparent upon presentation. Among the three CKD-EPI equations, eGFRCr-Cys performed most consistently across the studied patient populations.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, glomerular filtration rate, estimated GFR, Cystatin C, Creatinine, iothalamate

Introduction

Estimation of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) based on plasma creatinine has become standard practice to assess kidney function in routine clinical practice. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) recently developed two cystatin C-based eGFR equations to compliment the older creatinine-based equation. (1) The 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline (2) recommends use of a cystatin C-based eGFR to confirm an eGFR Cr 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2. All three CKD-EPI equations were developed from a mix of patients that included a majority of chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients (~70%) together with a sizable minority of healthier populations such as kidney donors (~30%), while transplant recipients were excluded.(1) Ideally, a single equation could accurately estimate GFR in all clinical situations. However, prior studies have demonstrated that comorbidities such as solid-organ transplant strongly influence the relationship between measured GFR and either creatinine, cystatin C, or both.(3, 4)

In the present study, we sought to evaluate the performance of the two new cystatin C-based eGFR equations compared to creatinine alone-based eGFR and GFR measured by iothalamate clearance. Our previous studies demonstrated that creatinine-based eGFR equations perform differently based on patient presentation.(5) Thus, we grouped our results according to patient categories readily identified in clinical practice: normal kidney donors, patients with known CKD, and solid organ transplant recipients.

Study Population and Methods

Patient Population

All patient data was accessed in compliance with the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The current study describes 1,652 consecutive stable ambulatory outpatients with a clinically ordered iothalamate clearance study performed in the Mayo Clinic Renal Function Laboratory. Consecutive patients included 887 transplant recipients (568 kidney; 319 other organ [non-kidney]), 147 potential kidney donors (no known CKD prior to evaluation), and 618 CKD patients (known or suspected CKD and without transplant; Table 1). Patients who underwent renal function assessment for chemotherapy dosing, were paraplegic, quadriplegic, <18 years of age, or amputees were excluded, since these features are known to alter muscle mass (and hence creatinine generation); furthermore there were insufficient numbers to study them separately.

Table 1.

Patient demographic information and overall renal function data.

| Demographics | Potential Kidney Donors | CKD Patients | Kidney Recipients | Other Organ Recipients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 147 | 618 | 568 | 319 |

| Age, mean±SD | 47 ±13 | 57 ±15 | 55 ±14 | 57 ±13 |

| Age <40 year, n (%) | 43 (29) | 63 (10) | 87 (15) | 33 (10) |

| Age >70 years, n (%) | 1 (1) | 75 (12) | 84 (15) | 36 (11) |

| Female, n (%) | 85 (58) | 253 (40) | 245 (43) | 139 (43) |

| African American, n (%) | 2 (1) | 12 (2) | 11 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Height (cm), mean±SD | 169 ±8 | 171 ±12 | 170±10 | 172±10 |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 80 ±19 | 84 ±20 | 85±22 | 82±18 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 28 ±4.7 | 29 ±5.7 | 29±6.7 | 28±4.8 |

| Renal function | ||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL)* | 0.9±0.2 | 1.5±1.0 | 1.5±0.6 | 1.3±0.5 |

| Serum cystatin C (mg/L)* | 0.80±0.17 | 1.44±0.74 | 1.59±0.54 | 1.52±0.47 |

| Measured GFR (mL/min/1.73m2)* | 101±22 | 66±33 | 55±19 | 58±24 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2)* | ||||

| eGFRCr | 87±17 | 63±30 | 53±18 | 56±22 |

| eGFRCys | 103±20 | 64±31 | 50±19 | 53±24 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 96±17 | 63±30 | 50±17 | 54±22 |

| Correlation with mGFR | ||||

| eGFRCr | 0.6485 | 0.8629 | 0.7459 | 0.7943 |

| eGFRCys | 0.6101 | 0.8653 | 0.7940 | 0.8583 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 0.7136 | 0.9047 | 0.8374 | 0.8913 |

mean±SD

Iothalamate Clearance, Serum Creatinine, Serum Cystatin C, and eGFR

GFR was measured by non-radiolabeled iothalamate clearance (mGFR). Patients were asked to fast and report for testing early in the day to minimize dietary and diurnal variations. Iothalamate was administered by subcutaneous injection following oral hydration to maintain a brisk urine flow, followed by timed collections of plasma and urine for iothalamate quantification by LC-MS/MS. (6) Iothalamate filtration rate was normalized to body surface area as estimated by the DuBois formula. (7)

Calculated GFR was corrected for body surface area and normalized to 1.73m2. Serum creatinine was assessed using a standardized enzymatic assay on a Roche Cobas chemistry analyzer (c701 or c501; Roche Diagnostics; Indianapolis, USA) while cystatin C was measured using an immunoturbidometric assay (Gentian; Moss, Norway) that was traceable to an international reference material. GFR was estimated (eGFR) using the CKD-EPI (2009) creatinine equation (eGFRCr), the CKD-EPI (2012) cystatin C only equation (eGFRCys) and the CKD-EPI (2012) combined equation which incorporates both creatinine and cystatin C (eGFRCr-Cys). (1, 8)

Statistical analysis

Equation performance was compared between the three different equations and the four different patient populations. The CKD-EPI equations were developed using least-squares regression of log GFR.(1) Thus, the equations were originally derived to minimize bias between log mGFR and log eGFR across levels of log eGFR. Correspondingly, our validation analysis replicated this same methodology. Comparison graphs were plotted using linear regression with log eGFR as x-axis and log mGFR as y-axis. A more detailed defence of this approach to assessing bias with eGFR is included in the Appendix (Supplemental Methods). Bias was calculated on a logarithmic scale (4, 5, 9) and presented as a percentage. Equation bias was regressed using a smoother fit (lambda = 1,000,000) to graphically depict bias across eGFR for each patient population. Concordance (% agreement) between eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and mGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was compared for each equation and each patient population. All statistical analysis was performed using JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Overall eGFR performance

Patient demographics and renal function are described in Table 1. Potential kidney donors were significantly younger, more likely to be female, had lower serum creatinine and cystatin C concentrations, and had higher mGFR compared to all other categories (p <0.001 all cases). There were no significant differences in height, weight, body-mass index (BMI) or race between any patient categories, and no significant differences in serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, or mGFR values between CKD patients and transplant recipients.

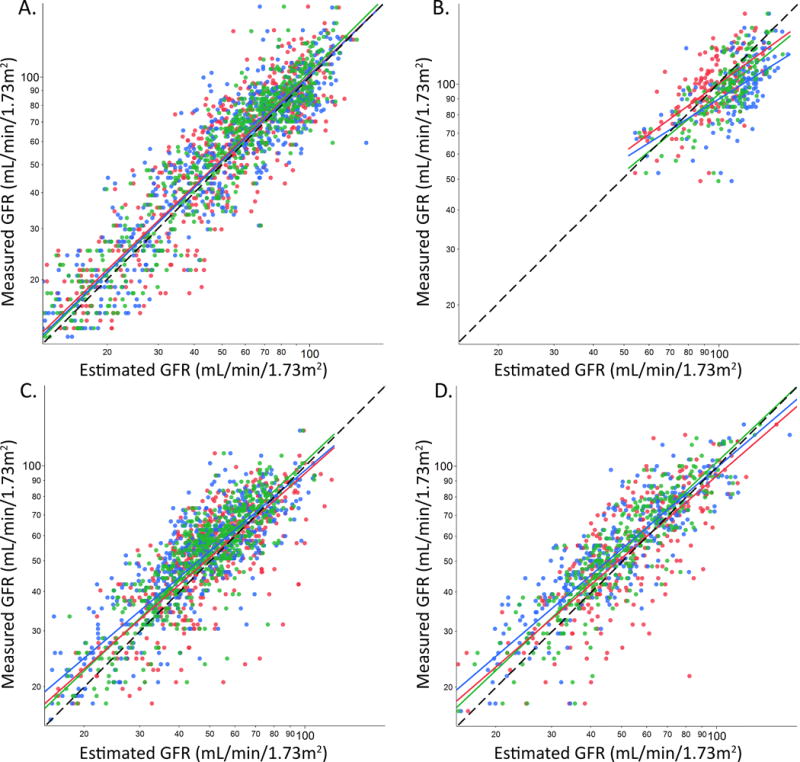

Measured GFR was plotted as a function of eGFR for each equation and patient group (Figure 1). Correlation with mGFR was weakest among potential kidney donors and strongest among CKD patients (Table 1). Among CKD patients and transplant recipients, correlation with mGFR was significantly stronger for eGFRCr-Cys, but not eGFRCys, when compared to eGFRCr (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Comparison of measured and estimated GFR according to equation and patient category.

Log eGFRCr (red), eGFRCys (blue) and eGFRCr-Cys (green) values are plotted on the x-axis and log mGFR on the y-axis for (A) CKD patients, (B) potential donors, (C) kidney transplant recipients, and (D) other organ (non-kidney) transplant recipients. The black dashed line represents the line of identity that an unbiased equation would follow.

Overall, all three equations modestly underestimated mGFR among CKD patients and transplant recipients. The mean difference between eGFR and mGFR among potential kidney donors was significantly smaller for eGFRCys and eGFRCr-Cys compared to eGFRCr (p <0.0001 both cases; Table 2). The mean bias between eGFR and mGFR was slightly but significantly larger for eGFRCys and eGFRCr-Cys compared to eGFRCr among transplant recipients (p <0.01 all cases). Equation performance did not statistically differ by gender (Supplemental Table 1). Equation bias decreased with age among other (non-kidney) organ transplant recipients for eGFRCr (p 0.02) and eGFRCr-Cys (p 0.02) but not eGFRCys (p 0.07; Supplemental Figure 1). No significant relationships with age were observed for any other equation or patient group.

Table 2.

Percent bias in different populations across clinically relevant eGFR ranges. Means with 95% confidence intervals that include zero are not significantly different from iothalamate corrected mGFR.

| eGFR | Potential Donors | CKD Patients | Kidney Recipients | Other Organ Recipients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||

| eGFRCr | −11.6 (−14, −8.9) | −0.8 (−3.0, 1.3) | 0.5 (−2.2, 3.2) | 1.3 (−2.2, 4.9) |

| eGFRCys | 4.8 (1.4, 8.1) | 0.1 (−1.9, 2.2) | −5.4 (−7.8, −3.0) | −7.7 (−10, −5.4) |

| eGFRCr-Cys | −2.7 (−5.4, 0) | −1.9 (−3.6, −0.2) | −4.8 (−7.0, −2.6) | −5.6 (−7.8, −3.5) |

| ≥90 mL/min/1.73m2 | ||||

| eGFRCr | −5.8 (−9.7, −1.9) | 5.0 (1.5, 8.6) | 29 (11.6, 46.4) | 13.5 (5.5, 22) |

| eGFRCys | 8.5 (4.9, 12.1) | 8.2 (4.7, 11.8) | 14.5 (4.8, 24.2) | 7.4 (0.8, 14) |

| eGFRCr-Cys | −1.4 (−4.5, 1.8) | 3.1 (−0.1, 6.3) | 6.7 (−3.4, 16.7) | 5.5 (−0.6, 12) |

| 60–89 mL/min/1.73m2 | ||||

| eGFRCr | −15 (−18.9, −11.2) | −4.0 (−7.4, −0.7) | 7.1 (2.1, 12.2) | 6.4 (−2.0, 15) |

| eGFRCys | −7.9 (−15.2, −0.6) | −2.4 (−5.7, 0.9) | 3.6 (0.3, 7) | −2.6 (−6.8, 1.5) |

| eGFRCr-Cys | −4.3 (−9.7, 1.1) | −5.0 (−7.5, −2.4) | −0.7 (−3.9, 2.6) | −4.7 (−8.6, −0.8) |

| 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2 | ||||

| eGFRCr | −20.5 (−27.3, −13.7) | −3.5 (−9.3, 2.3) | −6.3 (−9.7, −2.9) | −0.5 (−6.5, 5.6) |

| eGFRCys | −17.2 (−29.5, −4.8) | −7.3 (−12.3, −2.4) | −9.7 (−12.7, −6.8) | −7.2 (−12, −2.4) |

| eGFRCr-Cys | −18.5 (−28.7, −8.3) | −4.2 (−8.6, 0.1) | −7.9 (−10.8, −4.9) | −7.5 (−11, −3.7) |

| 30–44 mL/min/1.73m2 | ||||

| eGFRCr | – | −2.5 (−9.0, 4.1) | −2.9 (−7.9, 2.0) | −4.5 (−10, 1.5) |

| eGFRCys | – | −5.5 (−11, 0.0) | −11.3 (−16, −6.8) | −14.2 (−19, −9.7) |

| eGFRCr-Cys | – | −3.7 (−8.7, 1.3) | −7.8 (−12, −3.7) | −6.9 (−11, −2.5) |

| <30 mL/min/1.73m2 | ||||

| eGFRCr | – | 0.3 (−6.2, 6.8) | 5.2 (−10, 21) | −5.1 (−16, 6.0) |

| eGFRCys | – | 4.4 (−1.9, 11) | −6.1 (−17, 5.1) | −15.5 (−21, −10) |

| eGFRCr-Cys | – | 0.7 (−4.6, 6) | −0.1 (−12, 12) | −7.5 (−15, −0.1) |

Performance across levels of eGFR

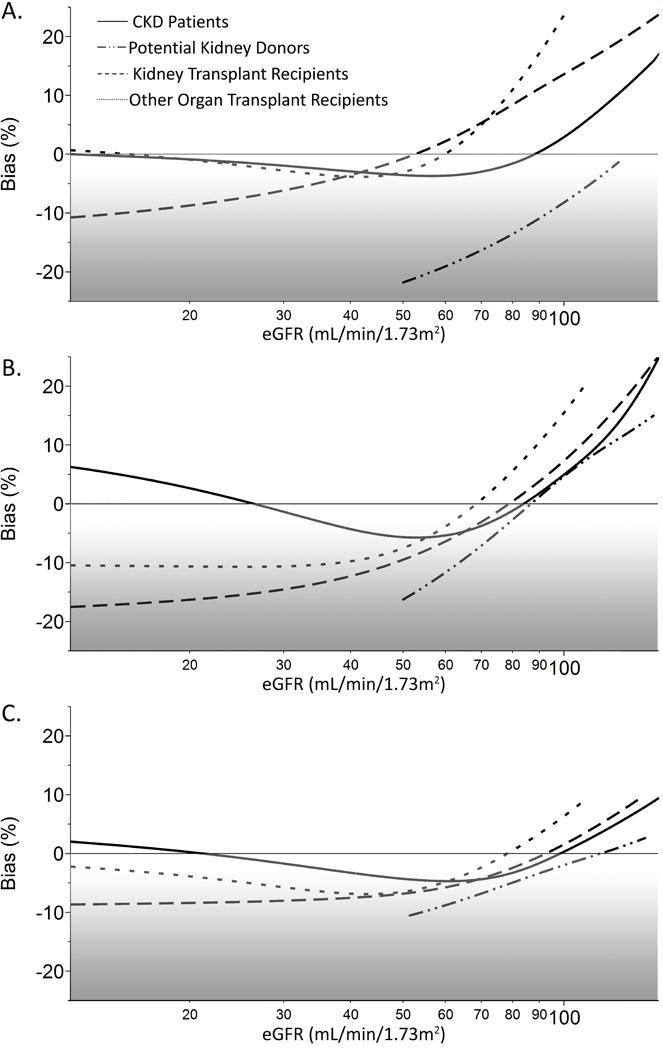

All eGFR equations tended to underestimate mGFR for all patient categories, with some differences in magnitude depending on patient group and equation (Figure 2). Bias was significantly smaller for eGFRCys and eGFRCr-Cys compared to eGFRCr among potential donors with eGFR >90mL/min/1.73m2 (p <0.001 both cases). The bias was significantly lower for eGFRCr-Cys (p=0.002), but not eGFRCys (p=0.087) compared to eGFRCr among potential donors with eGFR between 60–89 mL/min/1.73m2 (Table 2). Among both kidney and other organ transplant recipients eGFRCys was significantly more biased (negatively) than eGFRCr for values between 30–59 mL/min/1.73m2 (p<0.01; Table 2). Importantly, eGFR substantially underestimated mGFR for a mGFR between 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2 in all patients using either creatinine or cystatin C based equations (Table 2).

Figure 2. Equation bias as a function of eGFR.

Bias (exp[log eGFR − log mGFR] − 1) plotted as a function of (A) eGFRCr, (B) eGFRCys, and (C) eGFRCr-Cys for CKD patients (solid), potential kidney donors (dash-dot), kidney transplant recipients (dotted), and other-organ transplant recipients (dashed).

Clinical performance of eGFR equations

Finally, the concordance between eGFR and mGFR for classifying patients according to CKD stage was compared for each equation and patient category. Classification was considered across all CKD stages (Stage 1 >90, Stage 2 60–90, Stage 3a 45–59, Stage 3b 30–44, Stage 4 15–29, and Stage 5 <15 mL/min/1.73m2) or as a dichotomous function of greater or less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (Table 3). Concordance between eGFR <60 and mGFR <60 mL/min/1.73m2 was considered for each equation independently, and with confirming an eGFRCr between 45 – 59 mL/min/1.73m2 using eGFRCys or eGFRCr-Cys).

Table 3.

Concordance of estimated GFR with measured GFR when classifying patients between all CKD stages or dichotomously as <60 mL/min/1.73m2.

| All CKD Stages | <60 mL/min/1.73m2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordance, % (95CI) | p–value* | Concordance, % (95CI) | p–value* | |

| Potential Donors | ||||

| eGFRCr | 55.0 (47.0, 62.9) | – | 92.1 (87.8, 96.4) | – |

| eGFRCys | 71.5 (64.3, 78.7) | 0.002 | 93.4 (89.5, 97.4) | 0.63 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 76.2 (69.4, 83.0) | <0.001 | 94.1 (90.3, 97.9) | 0.45 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCys† | 56.3 (48.4, 64.2) | 0.81 | 94.7 (91.2, 98.3) | 0.30 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCr-Cys† | 57.6 (49.7, 65.5) | 0.64 | 94.7 (91.2, 98.3) | 0.30 |

| CKD Patients | ||||

| eGFRCr | 54.2 (50.3, 58.1) | – | 87.3 (84.7, 89.9) | – |

| eGFRCys | 58.7 (54.8, 62.6) | 0.11 | 88.1 (85.6, 90.7) | 0.66 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 62.9 (59.1, 66.7) | 0.002 | 89.7 (87.3, 92.1) | 0.18 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCys† | 57.9 (54.0, 61.8) | 0.19 | 91.3 (89.1, 93.5) | 0.02 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCr-Cys† | 58.4 (54.5, 62.2) | 0.14 | 90.5 (88.2, 92.8) | 0.07 |

| Kidney Transplant Recipients | ||||

| eGFRCr | 52.4 (48.4, 56.5) | – | 76.9 (73.5, 80.4) | – |

| eGFRCys | 55.1 (51.0, 59.1) | 0.37 | 77.6 (74.2, 81.0) | 0.78 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 58.0 (54.0, 62.1) | 0.06 | 79.2 (75.9, 82.5) | 0.35 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCys† | 52.1 (48.0, 56.2) | 0.12 | 78.5 (75.1, 81.9) | 0.52 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCr-Cys† | 53.8 (49.8, 57.9) | 0.6 | 78.5 (75.1, 81.9) | 0.52 |

| Other Organ Transplant Recipients | ||||

| eGFRCr | 46.9 (41.4, 52.3) | – | 80.1 (75.8, 84.5) | – |

| eGFRCys | 55.3 (49.8, 60.7) | 0.03 | 86.4 (82.6, 90.1) | 0.03 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 56.8 (51.4, 62.2) | 0.01 | 86.4 (82.6, 90.1) | 0.03 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCys† | 50.0 (44.5, 55.5) | 0.43 | 86.7 (82.9, 90.4) | 0.02 |

| eGFRCr/eGFRCr-Cys† | 51.6 (46.1, 57.0) | 0.23 | 84.8 (80.9, 88.7) | 0.11 |

P-value for comparison to eGFRCr.

Patient’s with eGFRCr between 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2 re-classified by eGFRCys or eGFRCr-Cys in comparison to eGFRCr

Concordance with mGFR was significantly better for eGFRCr-Cys compared to eGFRCr among the potential donors, CKD patients, and non-kidney transplant recipients (Table 3). Among potential donors and non-kidney transplant recipients eGFRCys also improved classification compared to eGFRCr alone. In both cases the improved concordance was primarily due to reclassification of patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2 or >60 mL/min/1.73m2 (Supplemental Table 2). Importantly, confirming an eGFRCr value between 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2 using eGFRCr-Cys or eGFRCys (according to KDIGO recommendations) only improved concordance with mGFR when classifying in relation to the 60 mL/min/1.73m2 cutoff in the CKD and other organ (non-kidney) transplant recipient groups.

Discussion

These data support previous evidence that eGFR equation performance is strongly dependent on patient presentation. However, in the current cohort significant differences in equation performance were limited to patients with stage 3B or greater CKD (GFR <45mL/min/1.73m2) and patients with good renal function (mGFR >60mL/min/1.73m2). The cystatin C equations (eGFRCys and eGFRCr-Cys) displayed significantly less bias than eGFRCr among potential donors but significantly more bias (negative) than eGFRCr among transplant recipients. Underestimation of mGFR by eGFRCr in donors is consistent with the higher muscle mass in healthy donors than is present in CKD patient populations.(10) Underestimation of mGFR by eGFRCys in transplant recipients is less clear but may be related to inflammation or immunosuppression effects on cystatin C.(11–13)

These findings support a strategy whereby the exact method used to assess GFR is chosen based on the type of patient being treated and the indication for testing. For example, there are certain circumstances where knowing the patient’s actual GFR (i.e. mGFR) is more important than a prediction of patient outcomes. A common example is dosing of renally cleared drugs.(14) In this situation, accurate estimation of GFR will enhance drug safety (avoidance drug toxicity) and efficacy (adequate dose for treatment). In the current study, eGFRCr-Cys was closest to mGFR across all patient groups and mGFR ranges, so might be the preferred default method for such purposes. Indeed, there is evidence that eGFRCr-Cys provides superior clinical performance in vancomycin dosing.(15, 16)

Alternatively, eGFR has been used to establish risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension and end-stage renal disease. Recent studies suggest that eGFRCys is a better predictor of patient morbidity and mortality than eGFRCr.(17–20) Conversely, eGFRCr is reported to more accurately detect the same risk factor and outcome associations seen with reduced mGFR compared to eGFRCys or eGFRCr-Cys.(21–24). The reasons are likely due to the underlying risk related to production of the biomarker or other non-GFR-related biology of cystatin C.(25–27) Thus, different biomarker derived eGFR equations might be chosen depending on the outcome of interest and/or clinical need.

In our cohort, the net effect of confirming eGFRCr between 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2 with either eGFRCys or eGFRCr-Cys was minimal and depended upon patient presentation. Among patients with known CKD, confirmation significantly improved appropriate classification of patients as having a mGFR<60mL/min/1.73m2. However, these patients were already diagnosed with CKD and the clinical value of the confirmatory testing is questionable. Only four potential donors had reduced mGFR <60 mL/min/1.73m2, and at least two (50%) would still have been misclassified as having eGFR>60 mL/min/1.73m2 regardless of the equation used.

Our study has certain limitations. The size of our cohort was less than that used to derive the CKD-EPI equations, and it contained very little racial/ethnic diversity. However, this cohort represents a relatively large group of patients with well-defined clinical diagnoses, standardized serum cystatin C and creatinine values, and mGFR using iothalamate clearance technique that was used to develop the CKD-EPI equations.

Moving forward, a conceptual shift may be helpful. Equations such as eGFRCr-Cys that perform reasonably well among all patient groups could be used to estimate GFR for patient treatments that are critically dependent on mGFR (e.g. dosing of vancomycin). On the other hand, if knowledge regarding patient prognosis is important, (e.g. risk of CKD progression or death), alternative models of care could be developed that incorporate biomarkers (e.g. cystatin C) and clinical characteristics to estimate risk of end stage renal disease or other key outcomes such as mortality, rather than accurately estimating mGFR. Targeted use of cystatin C in this context would offset the increased cost of cystatin C compared to creatinine, a potential consideration when additional testing is ordered.(28, 29)

In conclusion, in the current study the combined eGFRCr-Cys performs best across all patient types for predicting measured GFR. However, the performance of eGFR equations varies considerably across patient presentation and eGFR values. In particular, eGFRCr is not advised in kidney donor evaluations and eGFRCys or eGFRCr-Cys is not advised in transplant recipients.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Equation bias as a function of age. %Bias plotted as a function of age for (A) eGFRCr, (B) eGFRCys, and (C) eGFRCr-Cys.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mary Karaus, David Dvorak, and Laura Hanson of Mayo Validation Support Services and Jason Schilling and Michelle Soland of the Renal Studies unit for their assistance with the study. This study was partially funded by Gentian AS, who also supplied reagents used for the cystatin C PETIA, and by the Mayo Foundation. Research funding played no role in the study design, analysis, or interpretation of the data, nor the decision to submit the report for publication. Investigators were also supported by the Mayo Clinic O’Brien Urology Research Center (U54 DK100227; JCL and ADR), the Rare Kidney Stone Consortium (U54KD083908; JCL), a member of the NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), and R01 DK90358 (ADR and JCL) funded by the NIDDK and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Abbreviations

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- eGFRCr

creatinine estimated GFR

- eGFRCys

cystatin C estimated GFR

- eGFRCr-Cys

creatinine and cystatin C combined estimated GFR

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin c. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:20–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (kdigo) ckd work group. Kdigo 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;(Suppl 3):1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Bergert J, Larson TS. Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin c among different clinical presentations. Kidney Int. 2006;69:399–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaffi K, Uhlig K, Perrone RD, Ruthazer R, Rule A, Lieske JC, et al. Performance of creatinine-based gfr estimating equations in solid-organ transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:1007–18. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murata K, Baumann NA, Saenger AK, Larson TS, Rule AD, Lieske JC. Relative performance of the mdrd and ckd-epi equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate among patients with varied clinical presentations. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1963–72. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02300311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seegmiller JC, Burns BE, Fauq AH, Mukhtar N, Lieske JC, Larson TS. Iothalamate quantification by tandem mass spectrometry to measure glomerular filtration rate. Clin Chem. 2010;56:568–74. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.133751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Bois D, Du Bois E. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Int Med. 1916;17:863–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaeffner ES, Ebert N, Delanaye P, Frei U, Gaedeke J, Jakob O, et al. Two novel equations to estimate kidney function in persons aged 70 years or older. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:471–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roshanravan B, Patel KV, Robinson-Cohen C, de Boer IH, O’Hare AM, Ferrucci L, et al. Creatinine clearance, walking speed, and muscle atrophy: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:737–47. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathisen UD, Melsom T, Ingebretsen OC, Jenssen T, Njolstad I, Solbu MD, et al. Estimated gfr associates with cardiovascular risk factors independently of measured gfr. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:927–37. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight EL, Verhave JC, Spiegelman D, Hillege HL, de Zeeuw D, Curhan GC, de Jong PE. Factors influencing serum cystatin c levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1416–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lafarge JC, Naour N, Clement K, Guerre-Millo M. Cathepsins and cystatin c in atherosclerosis and obesity. Biochimie. 2010;92:1580–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rybak MJ. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(Suppl 1):S35–9. doi: 10.1086/491712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frazee EN, Rule AD, Herrmann SM, Kashani KB, Leung N, Virk A, et al. Serum cystatin c predicts vancomycin trough levels better than serum creatinine in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. Crit Care. 2014;18:R110. doi: 10.1186/cc13899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obiols J, Bargnoux AS, Kuster N, Fesler P, Pieroni L, Badiou S, et al. Validation of a new standardized cystatin c turbidimetric assay: Evaluation of the three novel ckd-epi equations in hypertensive patients. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:1542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waheed S, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Hoogeveen R, Ballantyne C, Coresh J, Astor BC. Combined association of albuminuria and cystatin c-based estimated gfr with mortality, coronary heart disease, and heart failure outcomes: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:207–16. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peralta CA, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Ix J, Fried LF, De Boer I, et al. Cystatin c identifies chronic kidney disease patients at higher risk for complications. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:147–55. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Judd S, Cushman M, McClellan W, Zakai NA, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease with creatinine, cystatin c, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and association with progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality. Jama. 2011;305:1545–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamora E, Lupon J, de Antonio M, Vila J, Penafiel J, Galan A, et al. Long-term prognostic value for patients with chronic heart failure of estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated with the new ckd-epi equations containing cystatin c. Clin Chem. 2014;60:481–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.212951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhavsar NA, Appel LJ, Kusek JW, Contreras G, Bakris G, Coresh J, Astor BC. Comparison of measured gfr, serum creatinine, cystatin c, and beta-trace protein to predict esrd in african americans with hypertensive ckd. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:886–93. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rule AD, Bailey KR, Lieske JC, Peyser PA, Turner ST. Estimating the glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine is better than from cystatin c for evaluating risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2013;83:1169–76. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathisen UD, Melsom T, Ingebretsen OC, Jenssen T, Njolstad I, Solbu MD, et al. Estimated gfr associates with cardiovascular risk factors independently of measured gfr. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;22:927–37. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melsom T, Mathisen UD, Ingebretsen OC, Jenssen TG, Njolstad I, Solbu MD, et al. Impaired fasting glucose is associated with renal hyperfiltration in the general population. Diabetes care. 2011;34:1546–51. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rule AD, Glassock RJ. Gfr estimating equations: Getting closer to the truth? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1414–20. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01240213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okura T, Jotoku M, Irita J, Enomoto D, Nagao T, Desilva VR, et al. Association between cystatin c and inflammation in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010;14:584–8. doi: 10.1007/s10157-010-0334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delanaye P, Cavalier E, Morel J, Mehdi M, Maillard N, Claisse G, et al. Detection of decreased glomerular filtration rate in intensive care units: Serum cystatin c versus serum creatinine. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo KS, Choi JL, Kim BR, Kim JE, Han JY. Clinical usefulness of serum cystatin c as a marker of renal function. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38:278–84. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, Ma H, Huang H, Wang C, Tang H, Li M, et al. Is the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration creatinine-cystatin c equation useful for glomerular filtration rate estimation in the elderly? Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1387–91. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S52774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Equation bias as a function of age. %Bias plotted as a function of age for (A) eGFRCr, (B) eGFRCys, and (C) eGFRCr-Cys.