Abstract

Background

The empirically derived 2014 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Mortality Risk Model incorporates adjustment for procedure type and patient-specific factors. The purpose of this report is to describe this model and its application in the assessment of variation in outcomes across centers.

Methods

All index cardiac operations in The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database (January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2013) were eligible for inclusion. Isolated patent ductus arteriosus closures in patients weighing less than or equal to 2.5 kg were excluded, as were centers with more than 10% missing data and patients with missing data for key variables. The model includes the following covariates: primary procedure, age, any prior cardiovascular operation, any noncardiac abnormality, any chromosomal abnormality or syndrome, important preoperative factors (mechanical circulatory support, shock persisting at time of operation, mechanical ventilation, renal failure requiring dialysis or renal dysfunction (or both), and neurological deficit), any other preoperative factor, prematurity (neonates and infants), and weight (neonates and infants). Variation across centers was assessed. Centers for which the 95% confidence interval for the observed-to-expected mortality ratio does not include unity are identified as lower-performing or higher-performing programs with respect to operative mortality.

Results

Included were 52,224 operations from 86 centers. Overall discharge mortality was 3.7% (1,931 of 52,224). Discharge mortality by age category was neonates, 10.1% (1,129 of 11,144); infants, 3.0% (564 of 18,554), children, 0.9% (167 of 18,407), and adults, 1.7% (71 of 4,119). For all patients, 12 of 86 centers (14%) were lower-performing programs, 67 (78%) were not outliers, and 7 (8%) were higher-performing programs.

Conclusions

The 2014 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Mortality Risk Model facilitates description of outcomes (mortality) adjusted for procedural and for patient-level factors. Identification of low-performing and high-performing programs may be useful in facilitating quality improvement efforts.

The assessment of variation in outcomes across pediatric and congenital cardiac surgical programs requires adjustment for differences in case mix across hospitals. Outcomes analysis without risk adjustment is misleading and can lead to risk aversion, with efforts made to avoid caring for the sickest of patients who might benefit the most from a cardiac operation [1–3]. The most common forms of risk adjustment for analysis and reporting of outcomes from pediatric and congenital cardiac surgery in use today are based mainly on the estimated risk of mortality of the primary procedural component of the operative encounter, as defined by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)—European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Congenital Heart Surgery (STAT) Mortality Categories [4, 5]. Because of the increased availability of robust clinical data, adding a variety of specific patient characteristics to pediatric and congenital cardiac surgical risk models is now possible [6].

The empirically derived 2014 STS Congenital Heart Surgery Database (STS-CHSD) Mortality Risk Model incorporates procedural factors and patient factors. This report describes this risk model and its application in the assessment of variation in pediatric and congenital cardiac surgical outcomes across centers.

Patients and Methods

Data Source

The STS-CHSD was used for this study. STS-CHSD is a randomly audited, comprehensive database of patients who have undergone congenital and pediatric cardiac surgical operations at centers in the United States and Canada. STS-CHSD is a voluntary registry that contains preoperative, operative, and outcomes data for all patients undergoing congenital and pediatric cardiovascular operations at participating centers. STS-CHSD uses the following age groupings: neonates (0 to 30 days), infants (31 days to 1 year), children (>1 year to <18 years), and adults (≥18 years).

The Report of the 2010 STS Congenital Heart Surgery Practice and Manpower Survey, undertaken by the STS Workforce on Congenital Heart Surgery, estimated that 125 hospitals in the United States and 8 hospitals in Canada perform pediatric and congenital heart operations [7]. In 2014, the STS-CHSD included 113 North American congenital heart surgical programs representing 119 of these 125 hospitals (95.2% penetrance by hospital) in the United States and 3 of the 8 centers in Canada.

Coding for this database is accomplished by clinicians and ancillary support staff using the International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code [8, 9] and is entered into the contemporary version of the STS-CHSD data collection form (version 3.0 was used in this report) [10]. The definitions of all terms and codes from the STS-CHSD used in this report have been standardized and published [10].

Evaluation of data quality in the STS-CHSD includes intrinsic verification of data (eg, identification and correction of values that are missing or out of range and inconsistencies across fields), along with a formal process of random site audits at approximately 10% of all participating centers each year conducted by a panel of independent quality personnel and pediatric cardiac surgeons [11]. Audit of the STS-CHSD has documented the following rates of completeness and accuracy for the specified fields of data [12]:

Primary diagnosis (completeness, 100%; accuracy, 96.2%)

Primary procedure (completeness, 100%; accuracy, 98.7%)

Mortality status at hospital discharge (completeness, 100%; accuracy, 98.8%)

The Duke Clinical Research Institute serves as the data warehouse and analytic center for all STS National Databases. Approval for this study was obtained from the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the Quality Measurement Task Force of the STS Workforce on National Databases.

Study Population

All index cardiac operations in the STS-CHSD during January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2013, inclusive, were eligible for inclusion (index operations are defined as the first cardiac operation of a hospitalization). Patients weighing less than or equal to 2.5 kg undergoing isolated closure of the patent arterial duct were excluded. Centers with more than 10% missing data and patients with missing data for discharge mortality or other key variables were excluded. The first 3.5 years of data were used for estimation, and the last 0.5 years were used as an independent validation set. The determination of outlier status of hospitals was based on all 4 years of data.

Table 1 documents the inclusionary and exclusionary criteria applied to obtain the final study cohort, which included 52,224 index cardiac operations from 86 centers from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2013, inclusive. Data collected included procedure type, patient age, weight, prematurity, chromosomal abnormalities, syndromes, noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormalities, preoperative factors, prior cardiac operation, primary procedure, and operative mortality.

Table 1.

Inclusionary and Exclusionary Criteria Applied to Obtain the Study Cohort

| Criteria | Records (No.) |

Participants (No.) |

|---|---|---|

| Starting population: cardiac operations performed 2010 to 2013, inclusive, with patient data collected under STS Version 3 or later at North America programs |

98,885 | 113 |

| Exclude data from 27 hospitals with <90% data completeness | (29,238 excluded) | |

| Exclude nonindex operations of a hospitalization | (11,480 excluded) | |

| Exclude PDA closures in ≤2.5 kg or organ procurement | (3,400 excluded) | |

| Exclude operations with an undefined STAT score | (1,302 excluded) | |

| Exclude operations with missing mortality | (937 excluded) | |

| Exclude operations with missing data for key model covariates | (304 excluded) | |

| Final population | 52,224 | 86 |

PDA = patent ductus arteriosus; STAT = The Society of Thoracic Surgeons—European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgery Mortality Categories.

The 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model

The STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model adjusts for the variables listed in Table 2. These variables include procedural stratification based on the primary procedure of each operation and also a variety of categories of patient characteristics, including prematurity, chromosomal abnormalities, syndromes, noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormalities, and preoperative factors. The factors coded in the STS-CHSD under the heading “Preoperative Factors” are patient preoperative “status” factors, such as preoperative mechanical circulatory support and preoperative renal dysfunction, among many others. These preoperative status factors can be distinguished from other patient characteristics, including patient-related genetic and structural factors that are included in the model, such as chromosomal abnormalities, syndromes, and noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormalities.

Table 2.

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Mortality Risk Model: List of Included Variables for Which the Model Adjusts

| Variable |

|---|

| Age group |

| Primary procedurea |

| Weight (neonates and infants) |

| Prior cardiothoracic operation |

| Any noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormality |

| Any chromosomal abnormality or syndrome |

| Prematurity (neonates and infants) |

Preoperative factors

|

The model adjusts for each combination of primary procedure and age group. Coefficients obtained by shrinkage estimation with The Society of Thoracic Surgery—European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgery Mortality Category as an auxiliary variable; see text for details.

Includes intraaortic balloon pump, ventricular assist device, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, mechanical cardiopulmonary support system.

The six specific “Preoperative Factors” incorporated into this model were selected from a previous report of 25,476 index cardiac operations performed in 23,019 patients at 72 centers from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2012 [6]. Preoperative factors selected for inclusion in the model included all factors whose association with discharge mortality was highly significant (p < 0.0001) for the three pediatric age categories (neonates, infants, and children): mechanical circulatory support, renal failure requiring dialysis or renal dysfunction (or both), shock, and mechanical ventilation, and factors whose association with discharge mortality was significant (p < 0.05) for all four age categories: preoperative mechanical ventilation and preoperative neurological deficit.

The detailed statistical methodology involved with the development and validation of this new 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model is described in a companion report [13]. As described in that report [13], a statistical technique known as empirical Bayes shrinkage estimation was adopted to account for small sample sizes when estimating the baseline risk associated with individual procedures. Briefly, the empirical Bayes estimator uses data from the entire ensemble of procedures in the database when estimating the risk for any single procedure. Heuristically, the empirical Bayes estimate is a weighted average of a procedure’s actual observed risk and a model-based estimate of risk derived from other similar procedures. The model weights the data of an individual procedure more heavily when the procedure-specific sample size is large enough to be reliable and weights the model-based prediction more heavily when the procedure-specific sample size is too small to be reliable. To further increase precision, the STAT Mortality Category of each procedure was incorporated in the shrinkage estimator. As a result, the estimated risk of each procedure is a weighted average of its actual observed risk and information borrowed from other procedures in the same STAT Mortality Category.

Variation Across Centers

Risk-adjusted mortality results for each center are expressed as the observed-to-expected (O/E) operative mortality ratio. The O/E ratio is defined as the number of observed deaths (numerator “O”) divided by the number of expected deaths (denominator “E”). The number of observed deaths is the center’s observed operative mortality. The number of expected deaths is determined by the 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model [13] and reflects the center’s case mix; that is, the mix of age, weight, procedure types, and other model-specific variables, including prior cardiothoracic operations, noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormalities, chromosomal abnormalities, syndromes, and preoperative risk factors. An O/E ratio exceeding 1.0 implies that the hospital had more deaths than would have been expected given the case mix. Conversely, an O/E ratio of less than 1.0 implies that the number of deaths was fewer than expected. Because small differences in the O/E ratio are usually not statistically significant and may reflect random statistical variation, O/E ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Centers were classified as having mortality that was lower than expected if their 95% CI for the O/E mortality ratio fell entirely below 1, higher than expected if their 95% CI for the O/E mortality ratio was entirely above 1, and same as expected if their 95% CI for the O/E mortality ratio overlapped 1. Data are presented documenting the number of centers that would fall into each of the three performance categories using 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99% CIs for the O/E mortality ratio.

Institutional Review Board Approval

The Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and provided a waiver of informed consent. Although the STS data used in the analysis contain patient identifiers, they were originally collected for nonresearch purposes, and the risk to patients was deemed to be minimal [14].

Results

The final analysis included 52,224 index cardiac operations with an overall operative mortality of 3.7% (n = 1,931). Table 3 reports operative mortality overall and stratified by age category.

Table 3.

Overall Operative Mortality and Operative Mortality Stratified by Age Category

| Variable | Overall | Neonates | Infants | Children | Adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operations, No. | 52,224 | 11,144 | 18,554 | 18,407 | 4,119 |

| Deaths, No. | 1,931 | 1,129 | 564 | 167 | 71 |

| Death, % | 3.7 | 10.1 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

Assessment of model fit and discrimination in the development sample and the validation sample reveals overall C statistics of 0.875 and 0.858, respectively.

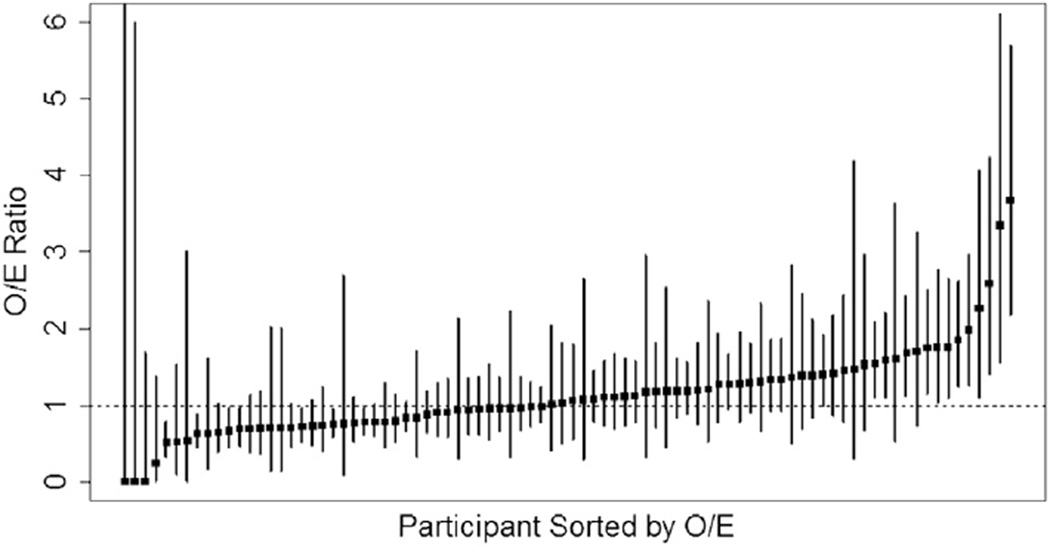

Variation across centers was assessed for all patients and within the age categories. Table 4 reports the distribution of institutions into performance categories with 4-year samples of data, for all patients and within age categories, by 95% CI for the O/E mortality ratio. Table 5 reports the number of centers identified as programs with mortality that was higher than expected, the same as expected, and lower than expected, using 4-year samples with 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99% CIs. Figure 1 shows the distribution of hospital-specific O/E ratios for operative mortality with 95% CIs.

Table 4.

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Mortality Risk Model: Performance Categories Using 95% Confidence Intervals

| Programs With Mortality That Is |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category | Total Programs No. (%) |

Higher Than Expected No. (%) |

Same As Expected No. (%) |

Lower Than Expected No. (%) |

| Neonates | 85 (100) | 8 (9) | 72 (85) | 5 (6) |

| Neonates and infants | 86 (100) | 11 (13) | 68 (79) | 7 (8) |

| Neonates, infants, and children | 86 (100) | 12 (14) | 67 (78) | 7 (8) |

| Neonates, infants, children, and adults | 86 (100) | 12 (14) | 67 (78) | 7 (8) |

Table 5.

Identification of Outliers Using 80%, 90%, 95%, and 99% Confidence Intervals for the Model Using Neonates, Infants, Children, and Adults

| Programs With Mortality That Is |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence Interval | Total Programs No. (%) |

Higher Than Expected No. (%) |

Same As Expected No. (%) |

Lower Than Expected No. (%) |

| 80% | 86 (100) | 19 (22) | 52 (60) | 15 (17) |

| 90% | 86 (100) | 13 (15) | 63 (73) | 10 (12) |

| 95% | 86 (100) | 12 (14) | 67 (78) | 7 (8) |

| 99% | 86 (100) | 6 (7) | 78 (91) | 2 (2) |

Fig 1.

Distribution of hospital-specific observed-to-expected (O/E) ratios for operative mortality with 95% confidence intervals (gray lines).

Comment

The earliest forms of risk adjustment used by STS-CHSD were based on complexity stratification, a method of analysis in which the data are divided into relatively homogeneous groups (called strata). The data are analyzed within each stratum. STS-CHSD currently uses three methods of procedural complexity stratification [6]: (1) The STAT Mortality Categories, (2) Aristotle Basic Complexity (ABC) levels, and (3) Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery-1 (RACHS-1) categories. The ABC score and ABC levels were incorporated in STS-CHSD in 2002. RACHS-1 categories were incorporated in STS-CHSD in 2006. RACHS-1 and the ABC scores were developed at a time when limited multiinstitutional clinical data were available and were, therefore, largely based on subjective probability (expert opinion). With the increasing availability of multiinstitutional clinical data, the STAT Mortality Score and STAT Mortality Categories were introduced in STS-CHSD in 2010.

These three methods provide three different ways of grouping types of pediatric and congenital cardiac operations according to their estimated risk or complexity. The STAT Mortality Categories are empirically derived from data in the STS and EACTS CHSDs and use five categories; the STAT Mortality Categories serve as the main complexity adjustment tool for the STS-CHSD. The ABC method uses four categories. The RACHS-1 method uses six categories but functionally has five categories when applied to STS-CHSD. STS and EACTS have transitioned from the primary use of ABC and RACHS-1 to the primary use of the STAT Mortality Categories.

For the past several years, risk adjustment in STS-CHSD has been based on estimated risk of death of the primary procedure of the operation, age, weight, and prematurity. Our previous report demonstrated the significant association of certain patient-specific preoperative risk factors with discharge mortality after operations for pediatric and congenital cardiac disease [6]. That previous report suggested that the inclusion of additional patient-specific preoperative factors in risk models for pediatric and congenital cardiac operations could lead to increased precision in predicting the risk of operative mortality and comparison of observed versus expected outcomes.

One of the limitations of current systems of risk stratification used for pediatric and congenital cardiac operations is the limited adjustment made for patient-specific factors. With the increased availability of verified clinical data, incorporating patient-specific factors into the risk models in the STS-CHSD is now possible. The empirically derived 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model incorporates adjustment for procedure type and patient-specific factors. The 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model is designed to facilitate comparison of observed versus expected operative mortality across centers but is not designed to function as a procedure-based risk calculator. Several procedure-specific factors have been added to the STS-CHSD to enhance future risk adjustment.

A short-term limitation of the 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model is the requirement that operations be coded with patient data collected under STS version 3 or later, whereas some operations performed in 2010 to 2013 (in patients who had prior cardiac operations) are coded in earlier versions of the database. Software updates will facilitate coding of the necessary fields for these operations under STS version 3 or later. Furthermore, coefficients of the final model will be reestimated twice yearly, using a 4-year analytic window, to coincide with the production of each STS-CHSD participant feedback report.

Future Directions

The new 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model includes a number of patient-specific characteristics, including prematurity, chromosomal abnormalities, syndromes, noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormalities, and preoperative factors. This present report describes this model and uses it to assess variation in outcomes across centers. This 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model will improve the ability of the STS-CHSD to be used as a tool to improve the quality of surgical care delivered to patients with pediatric and congenital cardiac disease [15–17]. It is anticipated that with the accumulation of larger numbers of patients and further understanding of the importance of various variables to each primary procedure or patient diagnosis, the C statistics will improve. The development of this risk model and the incorporation of these patient-specific preoperative data elements is a large step forward, but as in all new ideas, this model will require refinement.

In our prior STS-CHSD report [6], the only preoperative factors that were associated with operative mortality among adults undergoing operations for congenital heart disease were preoperative mechanical ventilation and preoperative neurological deficit. A specific tool for surgical risk adjustment for adults undergoing operations for congenital heart disease is currently under development. Many adults with congenital heart disease have unique preoperative factors, including ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Many of the preoperative factors in adults undergoing operations for congenital heart disease tend to be quite different from the preoperative factors present in neonates, infants, and children. Eventually, age-specific risk models will complement the overall risk models in the STS-CHSD.

In the January 2014 upgrade of the STS-CHSD, several “procedure-specific factors” were added to the data collection form. These new procedure-specific factors pertain to the previously published benchmark operations [16] and should eventually facilitate the development of procedure-specific risk models for these benchmark operations.

In reality, meaningful evaluation and comparison of outcomes require consideration of mortality and morbidity, but the latter is much harder to quantify. The observed versus expected operative mortality ratio is only one aspect of overall performance and should not be equated with overall performance of a surgical program. The STAT Mortality Categories are an empirically based tool that statistically estimates the risk of mortality associated with operations for congenital heart disease [4, 5]. The addition of patient characteristics, including prematurity, chromosomal abnormalities, syndromes, noncardiac congenital anatomic abnormalities, and preoperative factors, can enhance risk adjustment using the STAT Mortality Categories. To complement the evaluation of quality of care in pediatric and congenital cardiac surgery using the analysis of risk-adjusted mortality, STS has also developed a tool to analyze risk-adjusted morbidity: the STAT Morbidity Categories [18], which are based on major postoperative complications and postoperative length of stay. Major postoperative complications and postoperative length of stay were both used because models that assume a perfect one-to-one relationship between postoperative complications and postoperative length of stay are not likely to fit the data well. The STAT Morbidity Categories are an empirically based tool that statistically estimates the risk of morbidity associated with operations for congenital heart disease [18].

The new 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model described in this report adjusts for individual procedures, which is an even more granular adjustment than the STAT Mortality Category. Future initiatives to assess quality and improve outcomes using STS-CHSD will adjust for both mortality and morbidity based not only on the operation performed but also on patient-specific factors. In the future, when models have been developed that encompass other outcomes in addition to mortality, pediatric and congenital cardiac surgical performance may be able to be assessed using a multi-domain composite score that incorporates both mortality and morbidity and adjusts for the operation performed and patient-specific factors. It is our expectation that this information will also be publicly reported.

Conclusions

Current STS-CHSD risk adjustment is based on estimated risk of mortality of the primary procedure of the operation, age, and weight. The 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model includes additional patient-specific preoperative factors that lead to increased precision in predicting risk of operative mortality and comparison of observed versus expected outcomes. The 2014 STS-CHSD Mortality Risk Model can be used to describe center-level performance. Identification of low-performing and high-performing programs may facilitate quality improvement.

Footnotes

Presented at the Sixty-first Annual Meeting of the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, Tucson, AZ, Nov 5–8, 2014.

References

- 1.Jacobs JP, Cerfolio RJ, Sade RM. The ethics of transparency: publication of cardiothoracic surgical outcomes in the lay press. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:679–686. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahian DM, Edwards FH, Jacobs JP, et al. Public reporting of cardiac surgery performance: part 1–history, rationale, consequences. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(3 Suppl):S2–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahian DM, Edwards FH, Jacobs JP, et al. Public reporting of cardiac surgery performance: part 2–implementation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(3 Suppl):S12–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien SM, Clarke DR, Jacobs JP, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1139–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Maruszewski B, et al. Initial application in the EACTS and STS Congenital Heart Surgery Databases of an empirically derived methodology of complexity adjustment to evaluate surgical case mix and results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:775–780. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs JP, O’Brien SM, Pasquali SK, et al. The importance of patient-specific preoperative factors: an analysis of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:1653–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs ML, Daniel M, Mavroudis C, et al. Report of the 2010 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Practice and Manpower Survey. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:762–769. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Accessed December 30, 2013];International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code. Available: at http://www.ipccc.net.

- 9.Franklin RC, Jacobs JP, Krogmann ON, et al. Nomenclature for congenital and paediatric cardiac disease: historical perspectives and The International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl 2):70–80. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed July 4, 2014];STS Congenital Heart Surgery Database Data Specifications. Version 3.0. Available at: http://www.sts.org/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/CongenitalDataSpecificationsV3_0_20090904.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke DR, Breen LS, Jacobs ML, et al. Verification of data in congenital cardiac surgery. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl 2):177–187. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Mavroudis C, Tchervenkov CI, Pasquali SK. Executive summary: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database—twentieth harvest—(January 1, 2010—December 21, 2013) Durham, NC: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI), Duke University Medical Center; 2014. Spring. Harvest. [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien SM, Jacobs JP, Pasquali SK, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database mortality risk model: part 1—statistical methodology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dokholyan RS, Muhlbaier LH, Falletta J, et al. Regulatory and ethical considerations for linking clinical and administrative databases. Am Heart J. 2009;157:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Austin EH, et al. Quality measures for congenital and pediatric cardiac surgery. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2012;3:32–47. doi: 10.1177/2150135111426732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs JP, O’Brien SM, Pasquali SK, et al. Variation in outcomes for benchmark operations: an analysis of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:2184–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs JP, O’Brien SM, Pasquali SK, et al. Variation in outcomes for risk-stratified pediatric cardiac surgical operations: an analysis of the STS Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs ML, O’Brien SM, Jacobs JP, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing morbidity associated with operations for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1046.e1–1057.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]