Abstract

We describe a 65-year-old Thai woman who developed cytomegalovirus retinitis (CMVR) in the setting of Good syndrome—a rare, acquired partial immune deficiency caused by thymoma. The patient subsequently developed vitritis with cystoid macular edema (CME) similar to immune recovery uveitis (IRU) despite control of the retinitis with antiviral agents. A comprehensive review of the literature through December, 2014, identified an additional 279 eyes of 208 patients with CMVR in the absence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Including our newly reported case, 9 of the 208 patients (4.3 %) had Good syndrome. Twenty-one of the 208 patients (10.1 %) had CMVR related to intraocular or periocular corticosteroid administration. The remaining 178 patients (85.6 %) acquired CMVR from other causes. Within the subset of patients who did not have Good syndrome or did not acquire CMVR followed by intraocular or periocular corticosteroid administration, there were many other factors contributing to a decline in immune function. The most common included age over 60 years (33.1 %), an underlying malignancy (28.7 %), a systemic autoimmune disorder requiring systemic immunosuppression (19.1 %), organ (15.2 %) or bone marrow (16.3 %) transplantation requiring systemic immunosuppression, and diabetes mellitus (6.1 %). Only 4.5 % of the patients had no identifiable contributor to a decline in immune function. While the clinical features of CMVR are generally similar in HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients, the rates of moderate to severe intraocular inflammation and of occlusive retinal vasculitis appear to be higher in HIV-negative patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12348-016-0070-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Herpetic retinitis, Immunosuppression, Thymoma, Uveitis, Good syndrome

Review

Introduction

Thymoma is an uncommon and slow-growing neoplasm that accounts for approximately 20 to 30 % of mediastinal masses in adults and 1 % in children [1]. Thymic tumors not only usually present with respiratory symptoms due to compression of the upper airways and/or superior vena cava syndrome but also can produce paraneoplastic or parathymic syndromes [1–4], and the most common of which are myasthenia gravis (MG), pure red cell aplasia (PRCA), and acquired partial immune deficiency or Good syndrome [5, 6].

Good syndrome was first described by the American hematologist-oncologist Dr. Robert Good in 1956 [7]. Good noted a direct relationship between the presence of thymoma and hypogammaglobulinemia causing immunosuppression in those patients. Good syndrome typically occurs in middle-aged adults and is associated most commonly with recurrent sinus and pulmonary infections, cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease (most often retinitis), fungal infections, pure red cell aplasia, and myasthenia gravis [8]. While hypogammaglobulinemia in the setting of thymoma defines Good syndrome, other, often partial, immune deficiencies have also been described, including decreased T cell function [9].

We describe a 65-year-old woman who developed CMV retinitis (CMVR) in the setting of Good syndrome. The patient subsequently developed vitritis with cystoid macular edema (CME) despite control of the retinitis with antiviral agents. Cases of CMVR in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patients, including those with Good syndrome, identified in PubMed through December, 2014, were reviewed and are summarized. Search terms included “Cytomegalovirus AND eye” and “cytomegalovirus retinitis.” Additional publications were identified by reviewing collected references.

Case report

A 65-year-old Thai woman presented for evaluation of suddenly decreased vision with floaters in her right eye. Past ocular history was unremarkable. Past medical history was notable for PRCA diagnosed 2 years prior to presentation and for which she was treated for four months with erythropoietin and systemic corticosteroids. She also had two prior episodes of oropharyngeal candidiasis, which were treated successfully. There was no history of recent or current corticosteroid use.

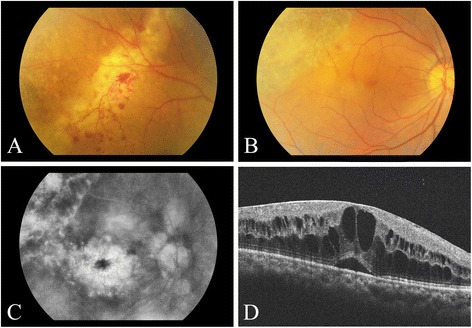

The best-corrected vision was 20/100 on the right eye and 20/25 on the left eye. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 15 mmHg bilaterally. No afferent pupillary defect was noted. Anterior segment examination of the right eye showed trace anterior chamber cell but was otherwise normal. Anterior segment examination on the left eye was unremarkable. Posterior segment examination on the right showed moderate vitreous inflammation and an advancing edge of necrotizing retinitis associated with scattered intraretinal hemorrhages and retinal vascular telangiectasis (Fig. 1a). Posterior segment examination of the left eye was unremarkable. The patient was diagnosed clinically with viral retinitis, an anterior chamber paracentesis was performed for viral DNA testing, a laser barrier was applied immediately posterior to the area of active retinitis, and the patient was given an intravitreal injection of 2 mg of ganciclovir followed by treatment with high-dose oral valaciclovir, 2 g three times daily. Analysis of the anterior chamber paracentesis was positive for CMV DNA, and the patient was switched from valaciclovir to valganciclovir, which resulted in resolution of the area of retinitis.

Fig. 1.

Color photograph of the patient’s right eye showing the active edge of cytomegalovirus retinitis (a), which became inactive following treatment with an intravitreal injection of 2 mg of ganciclovir followed by high-dose oral valaciclovir, 2 g three times daily (b). Fluorescein angiography (c) and SD-OCT imaging (d) showed the development of cystoid macular edema consistent with the diagnosis of immune recovery uveitis

The patient subsequently underwent HIV and syphilis testing, colonoscopy, chest X-ray, bone marrow biopsy, and abdominal CT, all of which were negative. Testing of immune function revealed a markedly decrease total B cell (CD19) cell count and panhypogammaglobulinemia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Immunologic profile over time of currently reported case of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the setting of thymoma (Good’s syndrome)

| Immunologic profile | At time of retinitis | At time of CME diagnosis and 5 months after thymoma resection | 6 months after CME and 11 months after thymoma resection | Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cells CD3 | 1079 (70 %) | N/A | 1284 (81 %) | 672–2638 cells/mL (54–83 %) |

| T helper cells CD4 | 480 (31 %) | N/A | 437 (28 %) | 292–1366 cells/mL (23.1–51.0 %) |

| Cytotoxic T cells CD 8 | 540 (35 %) | N/A | 817 (51 %) | 240–1028 cells/mL (17.9–47.5 %) |

| CD4 to CD8 ratio | 0.88 | N/A | 0.53 | 0.6–2.5 |

| B cells CD19 | 40 (3 %) | N/A | 26 (2 %) | 82–560 cells/mL (5.1–20.8 %) |

| Natural killer cells CD16/56 | 413 (27 %) | N/A | 277 (17 %) | 130–938 cells/mL (7.1–38.0 %) |

| Immunoglobulin G | 2.24 | 1.91 | N/A | 8–18 (g/L) |

| Immunoglobulin M | <0.06 | <0.06 | N/A | 0.5–2.2 (g/L) |

| Immunoglobulin A | <0.04 | 0.6 | N/A | 1.1–5.6 (g/L) |

Abbreviations: CME cystoid macular edema, CMV cytomegalovirus, NR not reported, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgM immunoglobulin M, CD cluster designation, NK natural killer, N/A not available

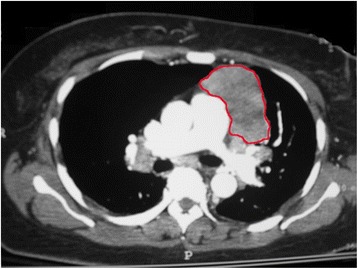

Within 1 month of the diagnosis of CMVR, the patient was hospitalized for acute pneumonia. During this hospitalization, a mediastinal mass was discovered on chest X-ray and evaluated further by chest CT (Fig. 2). Computer tomography guided thymus biopsy and subsequent thymectomy were performed, revealing histological changes consistent with thymoma that lead to the diagnosis of Good syndrome. Immunoglobulin A, G, and M levels remained low at the last testing 5 months following removal of the thymus. The patient then returned with worsening vision in the eye with CMVR while on maintenance valganciclovir therapy, 450 mg twice daily.

Fig. 2.

Chest CT showing a large mediastinal mass outlined in red and found subsequently to be a thymoma

The best-corrected vision was 20/125 on the right eye and 20/25 on the left eye. Intraocular pressure was normal. No afferent pupillary defect was noted. Anterior segment examination on the right showed several stellate keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelium, one cell per high powered field in the anterior chamber, and occasional anterior vitreous cells. Anterior segment examination on the left was unremarkable. Posterior segment examination on the right showed mild to moderate vitreous inflammation, a posterior vitreous detachment, a large area of inactive retinal necrosis (Fig. 1b), continuous laser barrier scars immediately posterior to the area of retinitis, and loss of the foveal light reflex suggestive of CME. Posterior segment examination on the left was unremarkable. Fluorescein angiography confirmed the presence of severe CME on the right (Fig. 1c). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) imaging showed marked CME on the right (Fig. 1d) with a central macular thickness of 743 um. SD-OCT imaging of the left fovea revealed a normal contour with no evidence of subretinal or intraretinal fluid. The patient was treated with topical difluprednate four times daily for 1 month. The CME persisted, the difluprednate was stopped, and the patient was given two injections of 1.25 mg of intravitreal bevacizumab, 1 month apart. The CME failed to respond, and so the patient was given an intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide, 2.0 mg, following which the CME resolved and vision improved to 20/80 in the affected eye. The CME subsequently recurred and the vision decreased to 20/100, but the patient refused further treatment. The retinitis remained inactive.

Comprehensive literature review

We describe a patient who developed CMVR in the setting of Good syndrome, a rare occurrence reported in eight previous patients to date (Tables 2 and 3) [10–16]. Including our patient, reported ages of the nine patients ranged from 48 to 68 years, with both a mean and median of 56 years. Women constituted just over half of the reported patients (55.5 %), with retinitis occurring unilaterally in all but one patient (88.9 %) and involving zone 1 in nearly two thirds of the affected eyes (62.5 %). When reported, anterior chamber inflammation was present in 62.5 % of cases; vitritis was present in 88.8 % of cases and was reported to be moderate to severe in five cases (55.5 %). The diagnosis was confirmed in all but one patient (89.9 %) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing of intraocular fluids, and all cases responded to antiviral therapy, which was administered both intravitreally and systemically in six of nine (66.6 %) patients. While the CMVR in our patient occurred 1 month prior to the identification of thymoma, a thymic tumor was identified prior to the development of CMVR in the other eight patients, with a time ranging from 1 month to just over 6 years prior to the occurrence of retinitis. Visual acuity at the initial CMVR diagnosis was between 20/40 and 20/200 in 77.8 and worse than 20/200 in 22.2 % of eyes, whereas visual acuity at last follow-up (median 6 months; range 1.5–7 months) was between 20/40 and 20/200 in 55.5 and worse than 20/200 in 44.4 % of eyes. Other common opportunistic infections reported in these nine patients with Good syndrome and CMVR included respiratory infections (77.8 %), non-ocular CMV (22.2 %), and herpes zoster dermatitis (33.3 %), whereas other autoimmune diseases (Table 3) included MG (25.0 %) and PRCA (22.2 %).

Table 2.

Summary of the current and previously reported cases of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in the setting of immunodeficiency associated with thymoma (Good syndrome)

| Author (year) | Age (years) | Gender | Unilateral (U) or bilateral (BL) | Timing of CMV retinitis relative to thymoma diagnosis (months) | Associated opportunistic infectionsa | Zone (involved)b | Retinitis treatmentc | CMV testing | Vision when retinitis was first diagnosed | Follow-up (months) | Vision at the last visit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously published cases | Ho et al. (2010) [10] | 68 | M | U | 75 months after thymoma | Recurrent pneumonia; disseminated CMV; CMV colitis | Zone I | IV ganciclovir and then PO valganciclovir | Lung biopsy | 20/200 | 1 | 20/100 |

| Mateo-Montoya et al. (2010) [11] | 57 | M | U | NR. “Long time after thymoma” | Recurrent pneumonia; Camplyobacter sepsis | Zone I | IVT ganciclovir, IVT foscarnet, and IV ganciclovir then PO valganciclovir | Aqueous PCR; vitreous PCR | 20/100 | 6 | 20/40 | |

| Park et al. (2009) [12] | 56 | M | BL | 3 months after thymoma | NR | Zone I and zone II | IVT ganciclovir and IV ganciclovir, then PO valganciclovir | Aqueous PCR; serum IgG | 20/800 OD, 20/125 OS | 6 | CF at 30 cm OD, NLP OS | |

| Sen et al. (2005)1 [13] | 48 | M | U | 60 months after thymoma | Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia; history of retinitis and optic neuropathy | Zone I | IVT ganciclovir and IVT ganciclovir implant (Vitrasert) | Aqueous PCR | 20/200 | 7 | 20/200 | |

| Wan et al. (2012) [14] | 51 | F | U | 60 months after thymoma | Recurrent sinopulomary infections; CMV enterocolitis | Zone II | PO valganciclovir then IVT ganciclovir weekly | Vitreous PCR | 20/40 | 6 | 20/50 then subsequently to CF due to the development of autoimmune retinopathy | |

| Yong et al. (2008) [15] | 50 | F | U | 6 months after thymoma | Herpes zoster (T10 dermatome) | NR | IV ganciclovir, then PO valganciclovir | Vitreous PCR | NR | 2 | NLP | |

| Assi et al. (2002) [16] case 1 | 45 | F | U | 24 months after thymoma | Recurrent pneumonia; zoster dermatitis | Zone II and zone III | IV valaciclovir, then IVT ganciclovir implant | Vitreous PCR | 20/40 | 6 weeks | NR | |

| Assi et al. (2002) [16] case 2 | 65 | F | U | 24 months after thymoma | Recurrent pneumonia | Zone I | IVT foscarnet then PO ganciclovir | Vitreous PCR | HM | NR | HM | |

| Current case | Downes, et al. (2016) | 65 | F | U | 1 month before thymoma | Oropharyngeal candidiasis; Candida esophagitis; pneumonia | Zone II and zone III | IVT ganciclovir, then PO valganciclovir | Aqueous PCR | 20/100 | 7 | 20/80 |

| Summary | Total n = 9 | Mean: 56 years | Male: 4/9 (44.4 %) | 8/9 (88.9 %) unilateral | Retinitis diagnosed after thymoma: 8/9 (88.9 %) | Respiratory infections: 7/9 (77.8 %) | Zone I: 5/8 reported (62.5 %) | Intravitreal therapy alone: 1/9 (11.1 %) | Positive aqueous PCR: 4/9 (44.4 %) | Acuity better than 20/40: 0/9 eyes (0.0 %) | Mean = 4.56 months | Acuity better than 20/40: 0/9 eyes (0.0 %) |

| Median: 56 years | Female: 5/9 (55.5 %) | Mean = 31.4 months after thymoma | Non-ocular CMV: 2/9 (22.2 %) | Zone II: 4/8 reported (50 %) | Systemic therapy alone: 2/9 (22.2 %) | Positive vitreous PCR: 5/9 (55.5 %) | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200: 7/9 eyes (77.8 %) | Median = 6 months | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200: 5/9 eyes (55.5 %) | |||

| Range: 48–68 years | Male to female ratio 0.8:1 | Median = 24 months after thymoma | Other opportunistic infections: 3/9 (33.3 %) | Zone III: 2/8 reported (25 %) | Combo intravitreal and systemic therapy: 6/9 (66.6 %) | Confirmed by other means: 1/9 (11.1 %) | Acuity worse than 20/200: 2/9 eyes (22.2 %) | Range = 1.5–7 months | Acuity worse than 20/200: 4/9 eyes (44.4 %) | |||

| Range = 75 months after to 1 month before |

Abbreviations: IgG immunoglobulin G, M male, F female, U unilateral, BL bilateral, CMV cytomegalovirus, NR not reported, CF count fingers, NLP no light perception, LP light perception, HM hand motion, IV intravenous, PO per oral, IVT intravitreal, PCR polymerase chain reaction

aAll patients were tested for HIV and found to be negative

bZone definitions are as follows: zone I defined as macula or optic nerve involvement; zone II defined as mid-periphery; and zone 3 defined as outer periphery. Zone definitions referenced in this paper: Cunningham ET Jr, Hubbard LD, Danis RP, Holland GN. Proportionate topographic areas of retinal zones 1, 2, and 3 for use in describing infectious retinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(11):1507–8 [115]

cDosing with each modality varied widely across studies

Table 3.

Summary of autoimmune conditions and immunologic parameters in current and previously reported cases of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in the setting of immunodeficiency associated with thymoma (Good syndrome)

| Author (year) | Myasthenia gravis | Pure red cell aplasia | Other conditions encountered | Lymphopeniaa | Low CD3+ T cells (<672 cells/mL or <54 %) | Low CD4+ count (<360/μL or <36 %) | A low CD8+ count (<240 cells/μL) | Low CD4+/CD8+ ratio (<0.6) | Low NK cells (<130 cells/mL or <7.1 %) | Hypogammaglobulinemia IgG (IgG < 8 g/L) | Hypogammaglobulinemia IgM (IgM <0.5 g/L) | Hypogammaglobulinemia IgA (IgA < 1.1 g/L) | Panhypogammaglobulinemia (I gG < 8 g/L, IgM <0.5 g/L, IgA < 1.1 g/L, or total Ig < 9.6 g/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously published cases | Ho et al. (2010) [10] | − | − | None | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mateo-Montoya et al. (2010) [11] | + | − | None | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | |

| Park et al. (2009) [12] | − | − | None | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | + | + | + | |

| Sen et al. (2005) [13] | − | − | ?neurosensory hearing loss and optic neuropathy | NR | NR | + | NR | + | NR | + | + | + | + | |

| Wan et al. (2012) [14] | NR | + | Autoimmune retinopathy (many years after diagnosis of retinitis) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Yong et al. (2008) [15] | − | − | None | + | − | + | − | + | NR | + | + | + | + | |

| Assi et al. (2002) [16] case 1 | + | − | None | − | NR | + | NR | + | NR | − | − | + | − | |

| Assi et al. (2002) [16] case 2 | − | − | None | NR | NR | NR | − | + | NR | + | + | + | + | |

| Current case | Downes, et al. (2013) | − | + | None | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Summary | Total n = 9 | +2/8 reported (25.0 %) | +2/9 cases (22.2 %) | No other definite autoimmune conditions encountered at the time of diagnosis of retinitis | +3/5 reported (60.0 %) | +1/3 reported (33.3 %) | +5/6 reported (83.3 %) | +0/4 reported (0.0 %) | +5/6 reported (83.3 %) | +1/2 reported (50.0 %) | +7/8 reported hypo IgG (87.5 %) | +7/8 reported hypo IgM (87.5 %) | +8/8 reported hypo IgA (87.5 %) | +7/8 reported panhypogammaglobulins (87.5 %) |

Abbreviations: CMV cytomegalovirus, NR not reported, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgM immunoglobulin M, CD cluster designation, NK natural killer

aBased on each individual lab standards and if reported by authors

Although the retinitis in our patient responded promptly to intravitreal and systemic antiviral agents, the patient subsequently developed vitritis and CME of the type seen in patients with immune recovery uveitis (IRU) despite the fact that her total CD4+ T cell count was normal both before and after the occurrence of retinitis. In contrast, the total B cell count and immunoglobulin levels where low both before and after thymectomy. While hypogammaglobulinemia is required to diagnose Good syndrome and has been observed in all reported cases to date, including our patient, it is noteworthy that the total CD4+ T cell count was somewhat decreased in five of the eight previously reported cases with Good syndrome and CMVR (Table 3), indicating that partial CD4+ T cell depletion does occur in patients with Good syndrome and suggesting the possibility that selective loss of CMV-targeting CD4+ T cells may have occurred in our patient, facilitating the development of retinitis. To our knowledge, an IRU-like syndrome has not been reported previously following treatment of CMVR in a patient with Good syndrome.

Our review identified a total of 248 eyes of 178 patients previously reported with CMVR in the absence of either HIV infection, Good syndrome, or prior periocular or intraocular corticosteroid injection (Additional file 1: Table S1) [17–86]. Reported ages ranged from 1 week to 84 years, with a mean and median of 45.7 and 48.0 years, respectively. Men outnumbered women approximately two to one (M to F ratio = 1.88:1), and the vast majority (95.5 %) had an identifiable cause of systemic immunosuppression. The most common factors contributing to a decline in immune function included age over 60 years (33.1 %), an underlying malignancy (28.7 %), a systemic autoimmune disorder requiring treatment (19.1 %), organ (15.2 %) or bone marrow (16.3 %) transplantation requiring systemic immunosuppression, and diabetes mellitus (6.1 %). The most commonly reported cancers included leukemia (35 patients; 19.7 %) and lymphoma (14 patients; 7.9 %). Three patients had multiple myeloma (1.7 %). One patient each (0.6 %) had breast cancer and angiocentric immunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Several patients had a primary immune deficiency other than Good syndrome, including three patients (1.7 %) with severe combined immunodeficiency, two patients each (1.1 %) with unspecified primary immune deficiency and common variable immune deficiency, and one patient (0.6 %) with idiopathic CD4+ T cell lymphopenia. Among the 26 reported patients less 18 years of age, 9 (34.6 %) had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 8 (30.8 %) had undergone bone marrow transplantation, 5 (19.2 %) had congenital CMV infection, 3 (11.5 %) had severe combined immunodeficiency and 1 each (3.8 %) had common variable immune deficiency and immunoglobulin 2 (Ig2) deficiency.

The use of systemic immunosuppressive medication was reported in 105 of 160 cases (65.6 %). Seventy-eight of these 105 patients (74.3 %) were on two or more immunosuppressive agents. Corticosteroids were the most common immunosuppressive agent used in 69 patients (65.7 %), followed by cyclophosphamide in 33 patients (31.4 %), azathioprine in 17 patients (16.2 %), vincristine in 16 patients (15.2 %), methotrexate in 15 patients (14.3 %), cyclosporine in 13 patients (12.4 %), tacrolimus in 11 patients (10.5 %), 6-mercaptopurine in 9 patients (8.6 %), mycophenolate mofetil in 8 patients (7.6 %), fludarabine in 7 patients (6.7 %), and adriamycin in 6 patients (5.7 %). Five patients each (4.8 %) used intravenous immunoglobulin G and rituximab. One patient each (1.0 %) was on mitoxantrone, ibritumomab tiuxetan, and hydroxychloroquine. Within the 105 cases reporting medication use, the use of either an antimetabolite or a leukocyte signaling inhibitor as a group (methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, or cyclosporine) was reported in 46.7 % of cases, whereas chemotherapeutic agents as a whole (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, high-dose methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, adriamycin, rituximab, fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and ibritumomab tiuxetan) were reported in 48.6 % of cases. Clinically, the retinitis was unilateral in 108 out of 178 cases (60.7 %). Many case reports provided limited clinical information, but the location was either reported or illustrated in 97 out of the 248 eyes (39.1 %) and was found to involve zone 1 in 72 eyes (74.2 %). Additional clinical features were noted in 200 out of 248 eyes (80.6 %). Among these, 200 eyes, or just under one third (29.0 %), were noted to have anterior chamber inflammation, which was described as mild in 18 (9.0 %) and moderate in 13 (6.5 %), and severe in the remaining 27 (13.5 %). Just over one third of the reported eyes (37.5 %) were noted to have vitreous inflammation, among which inflammation was described as mild in 23 (11.5 %), moderate in 18 (9.0 %), and severe in 6 (3.0 %), with the remaining 28 (14.0 %) not quantifying severity. An occlusive vasculitis was noted in 47 eyes (23.5 %). Visual acuity at initial CMVR diagnosis was reported in 179 of 248 eyes (72.2 %). Among these 179 eyes, visual acuity at initial diagnosis was better than 20/40 in 34.1 %, between 20/40 and 20/200 in 39.1 %, and worse than 20/200 in 26.8 % of eyes. The method of diagnostic confirmation of CMVR was reported in 131 of the 178 cases (73.6 %), among which the diagnosis of CMVR was confirmed by PCR-based testing of intraocular fluids in 71.8 %. The retinitis responded to antiviral therapy in all cases. The treatment administered was reported in 126 of the 178 cases (70.8 %). Of these 126 cases, systemic treatment was administered in 45.2 % of patients, whereas both intravitreal and systemic therapy was given in 31.0 % of patients, and intravitreal treatment alone was employed in 23.8 % patients. Visual acuity at the last follow-up visit was reported in 171 eyes (mean 14.2 months; median 6.0 months; range 0 to 216 months) and was better than 20/40 in 30.4 %, between 20/40 and 20/200 in 37.4 %, and worse than 20/200 in 32.2 % of eyes.

Recently, Takakura and colleagues reviewed the literature on patients who developed viral retinitis following intraocular or periocular administration of corticosteroids [87]. Out of a total of 30 reported cases, 21 (70.0 %) developed CMVR (Table 4) [33, 87–100]. These 21 patients constituted 10.1 % of the total of 208 non-HIV-positive patients with CMVR identified in our review. Among the 21 patients with CMVR, reported ages ranged from 30 to 84 years, with a mean and median of 66 and 69 years, respectively, and men outnumbered women two to one (M to F ratio = 2:1). The most common underlying ocular diseases for which corticosteroids were injected included diabetes mellitus (38.0 %), retinal vein occlusion (33.3 %), and uveitic CME (33.3 %), followed by choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration (9.5 %). In patients with uveitis and CMVR, Behcet’s disease and anterior uveitis comprised two cases each (28.5 %), followed by one case each (14.3 %) of anterior uveitis, Vogt-Koyangi-Harada disease, idiopathic posterior uveitis, and idiopathic panuveitis. The corticosteroid was administered intravitreally in 19 of the 21 eyes (90.5 %). Among these 19 patients who received intravitreal corticosteroids, 8 (38.0 %) were administered between 1.5 and 4 mg, 4 (19.0 %) were administered between 8 and 20 mg, and 1 (4.8 %) was administered 40 mg of triamcinolone acetonide. Two (9.0 %) were implanted with the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant (Retisert®). Among the two patients who received periocular corticosteroids, one (4.8 %) was administered 20 mg triamcinolone acetonide while the other patient (4.8 %) was administered 40 mg. The median time to developing retinitis after corticosteroid administration was 4.3 months with a mean of 4.0 months and a range 7 days to 13 months. Clinically, the retinitis involved zone 1 in 20.0 % of the eyes and was both unilateral and ipsilateral to the injection in all cases. Twelve out of 21 cases (57.1 %) described some clinical features of the retinitis. Within these 12 eyes, 10 (83.3 %) were noted to have anterior chamber inflammation, among which the inflammation was described as mild in one case (8.3 %) and moderate in four cases (33.3 %)—with the remaining seven (58.3 %) not quantifying severity. Over ninety percent of the eyes (91.6 %) were noted to have vitreous inflammation, among which inflammation was described as moderate in four eyes (33.3 %) with the remaining seven (63.6 %) not quantifying the severity of the inflammation. An occlusive vasculitis was noted in seven eyes (58.3 %). Visual acuity at initial CMVR diagnosis was reported in all 21 eyes and was better than 20/40 in 2 eyes (9.5 %), between 20/40 and 20/200 in 11 eyes (52.3 %), and worse than 20/200 in 8 eyes (38.0 %). The diagnosis was confirmed by PCR-based testing of intraocular fluids in 95.2 % of cases, and all cases responded to antiviral therapy, which was administered both intravitreally and systemically in 11 patients (52.3 %). Visual acuity at the last follow-up visit (mean 11.8 months; median 5.5 months; range 1–84 months) was better than 20/40 in 2 eyes (9.5 %), between 20/40 and 20/200 in 8 eyes (38.0 %), and worse than 20/200 in 11 eyes (52.3 %).

Table 4.

Summary of previously reported HIV-negative cases of cytomegalovirus retinitis following intraocular and periocular corticosteroid injection

| Previously published cases | Author (year) | Age (years) | Gender | Unilateral (U) or bilateral (BL) | Indication for corticosteroid | Corticosteroid dose/route | Time from corticosteroid dosing to retinitis (months) | CMV testing | Zone involveda | Vision when retinitis was first diagnosed | Retinitis treatmentb | Follow-up (months) | Vision at the last Visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saidel et al. (2005) [88] | 75 | M | U | DME | 4 mg IVTA | 4.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone I | 20/400 | IV ganciclovir, then IV valganciclovir, repeated IVT ganciclovir | 6 | 20/400 | |

| Delyfer et al. (2007) [89] Case 1 | 77 | M | U | CNVM/AMD | 20 mg IVTA | 4.0 | CMV retinitis (serology + PCR) | Zone II | CF at 1.8 m | IVT, IV valganciclovir | 6 | 20/200 | |

| Delyfer et al. (2007) [89] Case 2 | 69 | M | U | CRVO/DME | 8 mg IVTA three times over a 3-month interval | 3 (after the 3rd IVTA) | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone I | 20/200 | IV ganciclovir and IV valganciclovir | 3 | 20/400 | |

| Furukawa et al. (2007) [90] | 54 | F | U | DME | 10 mg IVTA | 4.0 | CMV retinitis (serology + PCR) | Zone II | 1 | IV ganciclovir; IVT foscarnet; vitrectomy and silicone oil tamponade | 14 | 0.5 | |

| Hsu et al. (2007) [91] | 77 | M | U | DME | 4 mg IVTA | 1.5 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 3/200 | Valganciclovir | 1 | 20/400 | |

| Ufret-Vincenty et al. (2007) [92] | 65 | M | U | Uveitic CME/Behcet’s disease | FA implant | 53 (after the 1st implant), 5 (after the 2nd implant) | CMV retinitis (“clinical diagnosis”) | Zone II | 20/50 | IVT foscarnet; ganciclovir implant | 5 | 20/40 | |

| Park et al. (2008) [93] | 77 | F | U | CRVO/CME due to HTN | 4 mg IVTA | 4.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | LP | IVT ganciclovir | 4 | HM | |

| Sekiryu et al. (2008) [94] | 63 | M | U | BRVO/DME | 4 mg IVTA | 7.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 0.1 | IV ganciclovir, IV valganciclovir | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Babiuch et al. (2010) [95] | 77 | M | U | Idiopathic iritis | 40 mg PST TA | 0.25 | CMV retinitis (serology + PCR) | Zone II | 20/40 | Vitrectomy, endolaser; IVT ganciclovir; ganciclovir implant | NR | NR | |

| Shah et al. (2010) [96] | 62 | M | U | BRVO/DME | 20 mg IVTA × 2 | 6.5 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 20/400 | IV valaciclovir; vitrectomy, endolaser and silicone oil; then IV valganciclovir | NR | NR | |

| Toyokawa et al. (2010) [97] | 83 | M | U | CNVM/AMD | 20 mg PST TA | 3.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 0.3 | PO valaciclovir, vitrectomy | 5 | 0.1 | |

| Tugal-Tutkun et al. (2010) [98] | 30 | M | U | Behcet’s panuveitis | IVTA dose NR | 3.5 | CMV retinitis (serology + PCR) | Zone I, zone II, zone III | 20/200 | IVT ganciclovir × 2; IV ganciclovir × 5 weeks; azathioprine changed to interferon alpha 2a | 8 | 20/60 | |

| Vertes et al. (2010) [99] | 78 | F | U | BRVO/CME | 4 mg IVTA | 3.0 | CMV retinitis (serology + PCR) | Zone II | 20/40 | IV ganciclovir; PO ganciclovir; IVT ganciclovir; then vitrectomy, endolaser | 8 | 20/25 | |

| Zaborowski et al. (2013) [100] | 56 | F | U | Idiopathic panuveitis/Uveitic CME | 4 mg IVTA | 6.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | CF | Azathioprine discontinued; intravitreal ganciclovir twice weekly for 3 weeks (2 mg) | 2 | NR | |

| Gupta et al. (2013) [32] case 1 | 70 | F | U | DME | IVTA dose NR | 4.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | CF | IVT foscarnet; IV valaciclovir; IVT foscarnet × 2; ganciclovir implant | 32 | CF | |

| Gupta et al. (2013) [32] case 2 | 60 | M | U | DME | IVTA NR | 6.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | NR | 20/400 | intravitreal foscarnet; IV valganciclovir; ganciclovir implant | NR | 20/300 | |

| Gupta et al. (2013) [32] case 3 | 84 | F | U | BRVO | IVTA NR | 6.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 20/150 | IVT foscarnet; IV valganciclovir | 19 | HM | |

| Takakura et al. (2013) [87] case 1 | 66 | M | U | VKH with steroid-induced cataracts and ocular hypertension, IVTA given during cataract surgery | 4 mg IVTA and ASCTA | 1.8 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 20/200 | IVT ganciclovir, PO valganciclovir; methotrexate and low-dose oral prednisone | 2 | 20/70 | |

| Takakura et al. (2013) [87] case 2 | 37 | F | U | Bilateral idiopathic posterior uveitis complicated by CME/retinal vasculitis | FA implant | 13.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone I | 20/80 | IVT foscarnet; PO valganciclovir | 2 | 20/100 | |

| Takakura et al. (2013) [87] case 3 | 63 | M | U | Granulomatous uveitis with CME | 40 mg IVTA × 2 | 3.0 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 20/60 | IV ganciclovir; PO prednisone; PPV | 84 | 20/200 | |

| Takakura et al. (2013) [87] case 4 | 72 | M | U | BRVO | 4 mg IVTA | 1.3 | CMV retinitis (PCR) | Zone II | 20/60 | IVT ganciclovir | 12 | CF | |

| Summary | N = 21 | Mean, 66.4 years | Male, 14/21 (66.6 %) | 21/21 (100 %) | RVO, 7/21 (33.3 %) | 1.5–4 mg IVT, 8/21 (38.0 %) | Mean, 4.3 months | Positive aqueous or vitreous PCR, 20/21 (95.2 %) | Zone I, 4/20 reported (20.0 %) | Acuity better than 20/40, 2/21 eyes (9.5 %) | Intravitreal therapy alone, 5/21 (23.8 %) | Mean = 11.8 months | Acuity better than 20/40: 2/21 eyes (9.5 %) |

| Median, 69 years | Female, 7/21 (33.3 %) | DME, 8/21 (38.0 %) | 8–20 mg, 5/21 (23.8 %) | Median, 4.0 months | Confirmed by other means: 1/21 (4.8 %) | Zone II, 17/20 reported (85.0 %) | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200, 11/21 eyes (52.3 %) | Systemic therapy alone, 5/21 (23.8 %) | Median = 5.5 months | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200: 8/21 eyes (38.0 %) | |||

| Range, 30.0–84.0 year | Male to female ratio, 2:1 | Uveitic CME, 7/21 (33.3 %) | 40 mg, 2/21 (9.0 %) | Range, 0.25–13.0 months | Zone III, 1/20 reported (5.0 %) | Acuity worse than 20/200, 8/21 eyes (38.0 %) | Intravitreal and systemic therapy, 11/21 (52.3 %) | Range = 1–84 months | Acuity worse than 20/200: 11/21 eyes (52.3 %) | ||||

| CNVM due to AMD, 2/21 (9.5 %) | FA implant, 2/21 (9.0 %) | ||||||||||||

| IRU, 0/21 (0.0 %) | Range, 1.5–40 mg |

Data used from paper done by Takakura et al (2013) currently in peer review Ocular Immunology and Inflammation

Abbreviations: AMD age-related macular degeneration, BRVO branch retinal vein occlusion, CRVO central retinal vein occlusion, CME cystoid macular edema, CNVM choroidal neovascular membrane, DME diabetic macular edema, ERM epi-retinal membrane, FA fluocinolone acetonide, IRU immune recovery uveitis, IgG immunoglobulin G, CMV cytomegalovirus, NR not reported, PCR polymerase chain reaction, CD cluster designation, NK natural killer, N/A not applicable

aZone definitions are as follows: zone I defined as macula or optic nerve involvement; zone II defined as mid-periphery; and zone 3 defined as outer periphery. Zone definitions referenced in this paper: Cunningham ET Jr, Hubbard LD, Danis RP, Holland GN. Proportionate topographic areas of retinal zones 1, 2, and 3 for use in describing infectious retinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(11):1507-8 [115]

bDosing with each modality varied widely across studies

The most complete and standardized description of CMVR in HIV-positive patients comes from the studies performed by the Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS (SOCA) research group [101–103]. Cytomegalovirus retinitis was the most frequently encountered complication of HIV infection in this cohort, occurring in 34.6 % of patients with CD4+ T cell counts <50 cells/μL and in 63.4 % of patients with CD4+ T cell counts <200 cells/μL [104]. Clinically, HIV-associated CMVR includes classic features of necrotizing retinitis with irregular sheathing of adjacent vessels and variable degrees of hemorrhage (sometimes referred to as “pizza pie retinopathy” or “cottage cheese with ketchup”), and which is sometimes coupled with a frost branch angiitis appearance without vascular occlusion and often associated with mild vitreous or anterior chamber inflammation [12, 20, 104]. In addition to these core clinical findings previously listed, the SOCA studies quantified the prevalence of a number of hallmark features of CMVR at presentation. Specifically, keratic precipitates were present in 36.8 % of the eyes with CMVR, anterior chamber inflammation in 46.2 %, and vitreous inflammation in 61.9 %. The prevalence of anterior chamber cells greater than 2+ was 1.9 % and vitreous haze greater than 2+ was 11.4 %. Macular edema, epiretinal membrane formation, and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment were each uncommon at presentation in the SOCA cohort, occurring in less than 10 % of the eyes, and posterior synechiae formation was not observed [104].

A number of studies have suggested that the clinical presentation of CMVR in HIV-negative patients can differ from that in HIV-positive patients [20–23, 27, 36, 94]. In a small series of eyes with CMVR in HIV-negative patients complied by Maguire and associates in 1995, three eyes were found to have spontaneously regressed or indolent appearing CMVR associated with vitritis and CME. The authors suggested that HIV-negative CMVR was more often associated with moderate to severe vitreous inflammation and CME [21]. The tendency for HIV-negative CMVR to have more severe intraocular inflammation as compared to CMVR in HIV-positive patients has since been noted by a number of authors, including Silverstein and colleagues [23], Voros and associates [27], Tajunisah and colleagues [25], Panthanapitoon and associates [22], and Schneider and colleagues [36] with specific mention of a similarity to acute retinal necrosis (ARN) in some eyes, including both the severity of the inflammation and the presence of occlusive vasculitis. In most instances, the more severe inflammation and vascular occlusion was ascribed to relative retention of anti-CMV immunoreactivity. However, other studies have failed to identify consistent difference in clinical presentation based on HIV status [18–20, 24, 26, 30–33, 37–40, 44, 94, 95]. In our review, of all the reported cases to date of HIV-negative CMVR not associated with Good syndrome or following intraocular or periocular administration of corticosteroids, clinical features of the inflammation were reported in 199 of the 248 eyes (80.2 %). Within these 199 eyes, 13 (6.5 %) were specifically described as having moderate to severe anterior chamber inflammation, 24 (12.1 %) as having moderate to severe vitreous inflammation, and 47 (23.6 %) were noted to have occlusive vasculitis. In HIV-negative CMVR associated with Good syndrome, clinical features of the inflammation were reported in all eyes. Within these 10 eyes, only 1 (10.0 %) was specifically described as having moderate to severe anterior chamber inflammation, whereas 5 out of 10 eyes (50.0 %) were described as having moderate to severe vitreous inflammation. None were noted to have occlusive vasculitis. In HIV-negative CMVR following intraocular or periocular administration of corticosteroids, clinical features of the inflammation were reported in 12 of the 21 eyes (57.1 %). Among these 12 eyes, 4 (33.3 %) each were described as moderate to severe anterior chamber inflammation or vitreous inflammation, and 6 (50.0 %) were noted to have occlusive retinal vasculitis. Hence, while an ARN-like picture including moderate to severe intraocular inflammation and the presence of occlusive vasculitis may be somewhat more common in HIV-negative as compared to HIV-positive CMVR, particularly in the setting of Good syndrome or following periocular or intraocular corticosteroids, the clinical presentation in these various cohorts appears, more often than not, to be fairly similar, with an overlapping clinical presentation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of cases of CMV retinitis in the literature without human immunodeficiency virus infection

| CMV retinitis following intraocular and periocular corticosteroid injectiona | CMV retinitis in the setting of immunodeficiency associated with thymoma (Good syndrome) | CMV retinitis in immunocompetent adults (non-Good syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | n = 21, n = 21 eyes | n = 9, n = 10 eyes | n = 178, n = 248 eyes |

| Age (years) | Mean, 66.4 years | Mean, 56 years | Mean, 45.7 years |

| Median, 69 years | Median, 56 years | Median, 48.0 year | |

| Range, 30.0–84.0 year | Range, 48–68 years | Range, 1 week–84 years | |

| Gender | Male, 14/21 (66.6 %) | Male, 4/9 (44.4 %) | Male, 113/173 reported (65.3 %) |

| Female, 7/21 (33.3 %) | Female, 5/9 (55.5 %) | Female, 60/173 reported (34.7 %) | |

| Male to female ratio, 2:1 | Male to female ratio, 0.8:1 | Male to female ratio, 1.88:1 | |

| % unilateral | 21/21 (100 %) | 8/9 (88.9 %) | 108/178 (60.7 %) unilateral |

| Indication for corticosteroid | RVO, 7/21 (33.3 %) | N/A | N/A |

| DME, 8/21 (38.0 %) | |||

| Uveitic CME, 7/21 (33.3 %) | |||

| CNVM due to AMD, 2/21 (9.5 %) | |||

| IRU, 0/21 (0.0 %) | |||

| Corticosteroid dose/route | 1.5–4 mg IVT, 8/21 (38.0 %) | N/A | N/A |

| 8–20 mg, 5/21 (23.8 %) | |||

| 40 mg, 2/21 (9.0 %) | |||

| FA implant, 2/21 (9.0 %) | |||

| Range, 1.5–40 mg | |||

| Time from corticosteroid dosing to retinitis (months) | Mean, 4.3 months | N/A | N/A |

| Median, 4.0 months | |||

| Range, 0.25–13.0 months | |||

| Timing of CMV retinitis relative to thymoma diagnosis (months)b | N/A | Retinitis diagnosed after thymoma, 8/9 (88.9 %) | N/A |

| Mean, 31.4 months after thymoma | |||

| Median, 24 months after thymoma | |||

| Range, 75 months after to 1 month before | |||

| Associated systemic diseasesb | N/A | Respiratory infections, 7/9 (77.7 %) | No underlying systemic illness, 9/178 (5.1 %) |

| Non-ocular CMV, 2/9 (22.2 %) | Organ or bone marrow transplant, 61/178 (34.3 %) | ||

| Other opportunistic infections, 3/9 (33.3 %) | Autoimmune disease, 34/178 (19.1 %) | ||

| Leukemia or lymphoma, 51/178 (28.7 %) | |||

| Primary immune deficiency, 10/178 (5.6 %) | |||

| Other systemic medical conditions, 24/178 (13.5 %) | |||

| Immunosuppressive medication | N/A | N/A | No medication, 55/160 reported (34.4 %) |

| Using medication, 105/160 reported (65.6 %) | |||

| Using multiple immunosuppressive medication, 78/105 (74.3 %) | |||

| Using chemotherapy, 51/105 (48.6 %) | |||

| Using antimetabolites or leukocyte signaling inhibitors, 49/105 (46.7 %) | |||

| Associated autoimmune diseases | N/A | Myasthenia gravis, 2/8 reported (25.0 %) | N/A |

| Pure red cell aplasia, 2/9 cases (22.2 %) | |||

| Associated immunologic laboratory abnormalities | N/A | Generalized lymphopenia: 3/5 reported (60.0 %) | N/A |

| Low CD3+ T cells (<672 /mL), 1/3 reported (33.3 %) | |||

| Low CD4+ T cells (<360/μL), 5/6 reported (83.3 %) | |||

| Low CD 8 count (<240 /μL), 0/4 reported (0.0 %) | |||

| Low CD4+/CD8+ ratio (<0.6), 5/6 reported (83.3 %) | |||

| Low NK cells (<130 /mL), 1/2 reported (50.0 %) | |||

| Low serum IgG (<8 g/L), 7/8 reported (87.5 %) | |||

| Low serum IgM (<0.5 g/L), 7/8 reported (87.5 %) | |||

| Low serum IgA (<1.1 g/L), 8/8 reported (87.5 %) | |||

| Panhypogammaglobulinemia, 7/8 reported (87.5 %) | |||

| CMV testing | Positive aqueous or vitreous PCR, 20/21 (95.2 %) | Positive aqueous PCR, 4/9 (44.4 %) | Positive aqueous PCR, 65/131 reported (49.6 %) |

| Confirmed by other means, 1/21 (4.8 %) | Positive vitreous PCR, 5/9 (55.5 %) | Positive vitreous PCR, 29/131 reported (22.1 %) | |

| Confirmed by other means, 1/9 (11.1 %) | Confirmed by other means, 37/131 reported (28.2 %) | ||

| Zone involvedc | Zone I, 4/20 reported (20.0 %) | Zone I, 5/8 reported (62.5 %) | Zone I, 72/97 eyes reported (74.2 %) |

| Zone II, 17/20 reported (85.0 %) | Zone II, 4/8 reported (50 %) | Zone II, 87/97 eyes reported (89.7 %) | |

| Zone III, 1/20 reported (5.0 %) | Zone III, 2/8 reported (25 %) | Zone III, 39/97 eyes reported (40.2 %) | |

| Vision when retinitis was first diagnosed | Acuity better than 20/40, 2/21 eyes (9.5 %) | Acuity better than 20/40, 0/9 eyes (0.0 %) | Acuity better than 20/40, 61/179 reported eyes (34.1 %) |

| Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200, 11/21 eyes (52.3 %) | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200, 7/9 eyes (77.7 %) | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200, 70/179 reported eyes (39.1 %) | |

| Acuity worse than 20/200, 8/21 eyes (38.0 %) | Acuity worse than 20/200, 2/9 eyes (22.2 %) | Acuity worse than 20/200, 48/179 reported eyes (26.8 %) | |

| Retinitis treatmentd | Intravitreal therapy alone, 5/21 (23.8 %) | Intravitreal therapy alone, 1/9 (11.1 %) | Intravitreal therapy alone, 30/126 reported (23.8 %) |

| Systemic therapy alone, 5/21 (23.8 %) | Systemic therapy alone, 2/9 (22.2 %) | Systemic therapy alone, 57/126 reported (45.2 %) | |

| Intravitreal and systemic therapy, 12/21 (52.3 %) | Intravitreal and systemic therapy, 6/9 (66.6 %) | Intravitreal and systemic therapy, 39/126 reported (31.0 %) | |

| Follow-up (months) | Mean = 11.8 months | Mean = 4.56 months | Mean = 14.2 months |

| Median = 5.5 months | Median = 6 months | Median = 6.0 months | |

| Range = 1–84 months | Range = 1.5–7 months | Range = 0–216 months | |

| Vision at the last visit | Acuity better than 20/40, 2/21 eyes (9.5 %) | Acuity better than 20/40, 0/9 eyes (0.0 %) | Acuity better than 20/40, 52/171 reported eyes (30.4 %) |

| Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200, 8/21 eyes (38.0 %) | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200, 5/9 eyes (55.5 %) | Acuity between 20/40 and 20/200,:64/171 reported eyes (37.4 %) | |

| Acuity worse than 20/200, 11/21 eyes (52.3 %) | Acuity worse than 20/200, 4/9 eyes (44.4 %) | Acuity worse than 20/200, 55/171 reported eyes (32.2 %) |

Abbreviations: AMD age-related macular degeneration, BRVO branch retinal vein occlusion, CRVO central retinal vein occlusion, CME cystoid macular edema, CNVM choroidal neovascular membrane, DME diabetic macular edema, ERM epiretinal membrane, FA fluocinolone acetonide, IRU immune recovery uveitis, IgG immunoglobulin G, CMV cytomegalovirus, NR not reported, PCR polymerase chain reaction, CD cluster designation, NK natural killer, N/A not applicable

aData used from paper done by Takakura et al. [89] currently in peer review “Ocular Immunology and Inflammation”

bAll patients were HIV negative

cZone definitions are as follows: Zone I defined as macula or optic nerve involvement; Zone II defined as mid-periphery; Zone 3 defined as outer periphery. Zone definitions referenced in this paper: Cunningham ET Jr, Hubbard LD, Danis RP, Holland GN. Proportionate topographic areas of retinal zones 1, 2, and 3 for use in describing infectious retinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(11):1507–8 [115]

dDosing with each modality varied widely across studies

Immune recovery uveitis has been well characterized in HIV-positive patients and is currently one of the most common causes of vision loss in patients with CMVR receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [104, 105]. While the occurrence of IRU has varied widely in HIV-positive cohorts receiving HAART, with reported rates ranging from 3.0 to 63.3 % [106], the inflammation generally occurs several weeks to months after initiating HAART, as the number of circulating CD4+ T cells increases. The clinical spectrum of IRU includes vitritis, papillitis, CME, epiretinal membrane formation, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal neovascularization, vitreomacular traction syndrome, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy [104–107].

Of the 248 eyes of 178 patients with CMVR in the absence of either HIV infection or Good syndrome that have been described in the literature (Additional file 1: Table S1), 16 eyes (6.5 %) of 10 patients had one or more features consistent with IRU [17, 20, 45, 50, 70]. Reported ages of these 10 patients ranged from 15 to 68 years, with a mean and median of 47.8 and 54 years, respectively. Men outnumbered women approximately two to one (M to F ratio = 2.3:1), and the 100 % of the cases had an identifiable cause of systemic immunosuppression. The most common factors contributing to a relative decline in immune function included an underlying malignancy (n = 3; 30.0 %), age over 60 years (n = 2; 20.0 %), an autoimmune disorder (n = 2; 20.0 %), organ (n = 3; 30.0 %) or bone marrow (n = 1; 10.0 %) transplantation requiring systemic immunosuppression, and diabetes mellitus (n = 1; 10.0 %). The three reported cancers included two patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and one patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The use of systemic immunosuppressive medication was reported in 8 out of the 10 cases (80.0 %). All of these patients were on two or more immunosuppressive agents. Corticosteroids were the most common immunosuppressive agent used in four patients (50.0 %), followed by cyclophosphamide in three patients (37.5 %), and two patients each (25.0 %) treated with vincristine and mycophenolate mofetil. One patient each (12.5 %) was treated with rituximab, fludarabine, methotrexate, and tacrolimus. Clinically, the retinitis was bilateral in 6 (60.0 %) out of 10 cases. Most case reports provided limited clinical information, and the location was either reported or illustrated in only 1 out of the 10 patients (10.0 %). In this patient, the retinitis was found to involve zone II. Additional clinical features were noted in 5 out of 16 eyes (31.3 %). Among these five eyes, just two eyes (40.0 %) were noted to have moderate anterior chamber inflammation. All five eyes (100.0 %) were noted to have vitreous inflammation, among which inflammation was described moderate to severe in all cases. An occlusive vasculitis was not present in any reported case of CMVR associated with IRU. Visual acuity at initial CMVR diagnosis was reported in 15 out of 16 eyes (93.8 %). Among these 15 eyes, visual acuity at initial diagnosis was better than 20/40 in 40.0 %, between 20/40 and 20/200 in 53.3 %, and worse than 20/200 in 6.7 % of eyes. The method of diagnostic confirmation of CMVR was reported in 1 of the 10 cases (10.0 %), among which the diagnosis of CMVR was confirmed serum PCR testing. The retinitis responded to antiviral therapy in all cases. The therapeutic treatment administered was reported in 6 of the 10 cases (60.0 %). Of these 6 cases, treatment was administered systemically only in 33.3 % of patients and intravitreally alone in 66.7 % patients. Visual acuity at last follow-up visit was reported in 8 patients and 13 eyes (mean 22.2 months; median 19 months; range 1 to 43 months). Visual acuity at last follow-up was better than 20/40 in 38.5 %, between 20/40 and 20/200 in 46.1 %, and worse than 20/200 in 15.4 % of eyes.

Since the December, 2014, cutoff for our literature review, there have been several publications of CMVR in HIV-negative patients [108–113]. While these publications are not incorporated into this review, the clinical context in which CMVR developed and the clinical characteristics of the retinitis and the treatment(s) given for the infection were not significantly different from those previously reported or from the conclusions drawn by our review [114].

Conclusions

Although uncommon, CMVR can occur in the absence of HIV infection. Over 95 %, of HIV-negative patients who developed CMVR were found, ultimately, to have one or more factors contributing to a relative decline in immune function, such as advanced age, an underlying malignancy, an autoimmune disease or organ/bone transplantation requiring systemic immunosuppression, administration of periocular or intraocular corticosteroids, diabetes mellitus, or, less commonly, an inherited or acquired immune disorder, such as Good syndrome. While the clinical features of CMVR were generally similar in HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients, accumulated data regarding the rate of moderate to severe intraocular inflammation and occlusive retinal vasculitis would seem to suggest that these more ARN-like features occur more often in HIV-negative patients.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported in part by The Pacific Vision Foundation and The San Francisco Retina Foundation (ETC.).

Additional file

Summary of reported cases of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in immunocompetent HIV-negative patients. (DOC 497 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KD is the primary author who was responsible for conceiving the study, the acquisition of the data, and the analysis and interpretation. He drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for content. DT and LW were also responsible for the acquisition of the data and reading and approving the final manuscript. ETC was responsible for conceiving the study, participated in the review design, and revised the manuscript critically for content. ETC read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Kenneth M. Downes, M.D. is a resident physician at California Pacific Medical Center. Dariusz Tarasewicz, M.D., Ph.D. is a physician at the Department of Ophthalmology at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in South San Francisco, California. Laurie J. Weisberg, MD is a physician at the Department of Hematology/Oncology at Kaiser Permanente South San Francisco Medical Center in South San Francisco, California. Emmett T. Cunningham Jr., M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D. is a physician at the West Coast Retina Medical Group in San Francisco, California.

References

- 1.Liang X, Lovell MA, Capocelli KE, et al. Thymoma in children: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2010;13(3):202–208. doi: 10.2350/09-07-0672-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cucchiara BL, Forman MS, McGarvey ML, et al. Fatal Subacute Cytomegalovirus Encephalitis Associated with Hypogammaglobulinemia and Thymoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(2):223–227. doi: 10.4065/78.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelleher P, Misbah SA. Review: What is Good's syndrome? Immunological abnormalities in patients with thymoma. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(1):12–16. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitamura A, Takiguchi Y, Tochigi N, et al. Durable Hypogammaglobulinemia Associated with Thymoma (Good syndrome) Inter Med. 2009;48(19):1749–1752. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leibovitz I, Zamir D, Polychuck I, et al. Brief report. Recurrent Pneumonia Post-Thymectomy as a Manifestation of Good Syndrome. Eur J of Intern Med. 2003;14(1):60–62. doi: 10.1016/S0953-6205(02)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson MR, et al. Immune-Recovery Uveitis in Patients With Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Taking Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Am J Ophthalmol . 2000;130(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Good RA, et al. Thymic Tumor and Acquired Agammaglobulinemia: A Clinical and Experimental Study of the Immune Response. Surgery. 1956;40(6):1010–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelesidis T, et al. Good's Syndrome Remains a Mystery After 55 years: A Systematic Review of the Scientific Evidence. Clinical Immunology. 2010;135:347–363. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miao H, Tao Y, Jiang YR, Li XX. Multiple intravitreal injections of ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus retinitis after stem-cell transplantation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(7):1829–33. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho JK, et al. A rare combination of recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, and visual loss in a patient after thymectomy: Good syndrome. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16(6):493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mateo-Montoya A, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis associated with Good’s Syndrome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(2):479–480. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park D, et al. Bilateral Cytomegalovirus Retinitis with Unilateral Optic Neuritis in Good Syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54(3):246–8. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0795-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen H, et al. CMV Retinitis in a Patient with Good Syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:475–478. doi: 10.1080/09273940590950963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan C, et al. Autoimmune Retinopathy in Benign Thymoma after Good Syndrome-associated Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(1):64–66. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2012.730652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yong D, et al. Good’s syndrome in a patient with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:142–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assi A, et al. Cytomeagalovirus retinitis in Patients with Good Syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(4):510–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bessho K, Schrier RD, Freeman WR. Immune Recovery Uveitis in a CMV Retinitis Patient Without HIV Infection. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2007;I:52–53. doi: 10.1097/01.ICB.0000256952.24403.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chawla HB, Ford MJ, Munro JF, Scorgie RE, Watson AR. Ocular involvement in cytomegalovirus infection in a previously healthy adult. Br Med J. 1976;2(6030):281–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6030.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.England AC, 3rd, Miller SA, Maki DG. Ocular Findings of Acute Cytomegalovirus Infection in an Immunologically Competent Adult. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:94–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207083070204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo IC, Kempen JH, Dunn JP, Vogelsang G, Jabs DA. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in persons without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(3):338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maguire AM, Nichols CW, Crooks GW. Visual loss in cytomegalovirus retinitis caused by cystoid macular edema in patients without the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(4):601–5. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pathanapitoon K, Tesavibul N, Choopong P, Boonsopon S, Kongyai N, Ausayakhun S, Kunavisarut P, Rothova A. Clinical manifestations of cytomegalovirus-associated posterior uveitis and panuveitis in patients without human immunodeficiency virus infection. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(5):638–45. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverstein BE, Conrad D, Margolis TP, Wong IG. Cytomegalovirus-associated acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(2):257–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)71046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart MW, Bolling JP, Mendez JC. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in an immunocompetent patient. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(4):572–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tajunisah I, Reddy SC, Tan LH. Acute retinal necrosis by cytomegalovirus in an immunocompetent adult: case report and review of the literature. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29(2):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Contreras J, Ris J, Domingo P, Puig M, Rabella N, Nolla J. Disseminated cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent adult successfully treated with ganciclovir. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27(5):523–5. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voros GM, Pandit R, Snow M, Griffiths PG. Unilateral recurrent acute retinal necrosis syndrome caused by cytomegalovirus in an immune-competent adult. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16(3):484–6. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran TH, Rozenberg F, Cassoux N, Rao NA, LeHoang P, Bodaghi B. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of aqueous humour samples in necrotising retinitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(1):79–83. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radwan A, Metzinger JL, Hinkle DM, Foster CS. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompetent patients: case reports and literature review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(4):324–8. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.786095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aghamohammadi A, Abolhassani H, Hirbod-Mobarakeh A, Ghassemi F, Shahinpour S, Behniafard N, Naghibzadeh G, Imanzadeh A, Rezaei N. The uncommon combination of common variable immunodeficiency, macrophage activation syndrome, and cytomegalovirus retinitis. Viral Immunol. 2012;25(2):161–5. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coors LE, Spencer R. Delayed presentation of cytomegalovirus retinitis in an infant with severe congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Retina. 2010;30(4 Suppl):S59–62. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181c7018d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta S, Vemulakonda GA, Suhler EB, Yeh S, Albini TA, Mandelcorn E, Flaxel CJ. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in the absence of AIDS. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48(2):126–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moritake H, Kamimura S, Kojima H, Shimonodan H, Harada M, Sugimoto T, Nao-I N, Nunoi H. Cytomegalovirus retinitis as an adverse immunological effect of pulses of vincristine and dexamethasone in maintenance therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):329–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mota A, Breda J, Silva R, Magalhães A, Falcão-Reis F. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in an immunocompromised infant: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2(2):238–42. doi: 10.1159/000330550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samia L, Hamam R, Dbaibo G, Saab R, El-Solh H, Abboud M. Muwakkit S. Leuk Lymphoma: Cytomegalovirus retinitis in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Lebanon; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider EW, Elner SG, van Kuijk FJ, Goldberg N, Lieberman RM, Eliott D, Johnson MWCHRONICRETINALNECROSIS. Cytomegalovirus Necrotizing Retinitis Associated With Panretinal Vasculopathy in Non-HIV Patients. Retina. 2013;33(9):1791–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318285f486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh R, Singh R, Trehan A, Jain R, Bhalekar S. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in an ALL child on exclusive chemotherapy treated successfully with intravitreal ganciclovir alone. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(3):e118–9. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31827078ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Squires JE, Sisk RA, Balistreri WF, Kohli R. Isolated unilateral cytomegalovirus retinitis: a rare long-term complication after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17(1):E16–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svozílková P, Heissigerová J, Brichová M, Kalvodová B, Dvořák J, Ríhová E. A possible coincidence of cytomegalovirus retinitis and intraocular lymphoma in a patient with systemic non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Virol J. 2013;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakai K, Sano H, Shimada A, Shiozawa Y, Park MJ, Sotomatsu M, Yanagisawa R, Koike K, Kozawa K, Ryo A, Tsukagoshi H, Kimura H, Hayashi Y. Cytomegalovirus retinitis during maintenance therapy for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(2):162–3. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318279e920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Squirrell DM. Bhatta S. Rennie IG. Hypertensive iridocyclitis associated with delayed onset biopsy proven Cytomegalovirus retinitis. Indian J Ophthalmol: Mudhar HS; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takayama K, Ogawa M, Mochizuki M, Takeuchi M. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with proliferative diabetes retinopathy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(3):225–6. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2012.762983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yashiro S, Fujino Y, Tachikawa N, Inamochi K, Oka S. Long-term control of CMV retinitis in a patient with idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19(2):316–20. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0464-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moss HB, Chavala S, Say E, Miller MB. Ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in a patient with wild-type CMV in her plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(5):1796–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00029-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agarwal A, et al. Outcome of cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunocompromised patients without Human Immunodeficiency Virus treated with intravitreal ganciclovir injection. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Feb 21, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Bertelmann E, Liekfeld A, Pleyer U, Hartmann C. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in Wegener's granulomatosis: case report and review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83(2):258–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chou PI, Lee H, Lee FY. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after heart transplant: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1996;57(4):310–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Church J, Goyal S, Tyagi AK, Scott RA, Stavrou P. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eye (Lond). 2007;21(9):1230–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Egli A, Bergamin O, Müllhaupt B, Seebach JD, Mueller NJ, Hirsch HH. Cytomegalovirus-associated chorioretinitis after liver transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10(1):27–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2007.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eid AJ, Bakri SJ, Kijpittayarit S, Razonable RR. Clinical features and outcomes of cytomegalovirus retinitis after transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10(1):13–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2007.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gooi P, Farmer J, Hurley B, Brodbaker E. Cytomegalovirus retinitis mimicking intraocular lymphoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(4):969–71. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haerter G, Manfras BJ, de Jong-Hesse Y, Wilts H, Mertens T, Kern P, Schmitt M. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(9):e88–94. doi: 10.1086/425123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoang QV, Simon DM, Kumar GN, Oh F, Goldstein DA. Recurrent CMV retinitis in a non-HIV patient with drug-resistant CMV. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248(5):737–40. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishikawa K, Ando Y, Narita M, Shinjoh M, Iwasaki T. Cytomegalovirus retinitis during immunotherapy for common variable immunodeficiency. J Infect. 2002;44(1):55–6. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaulfersch W, Urban C, Hauer C, Lackner H, Gamillscheg A, Slavc I, Langmann G. Successful treatment of CMV retinitis with ganciclovir after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1989;4(5):587–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim HR, Kim SD, Kim SH, Yoon CH, Lee SH, Park SH, Kim HY. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(5):801–3. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobayashi R, Takanashi K, Suzuki D, Nasu T, Uetake K, Matsumoto Y. Retinitis from cytomegalovirus during maintenance treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Int. 2012;54(2):288–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lafaut BA, Vianna RN, De Baets F, Meire F. Unilateral cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with immunoglobulin G2 deficiency. Ophthalmologica. 1995;209(1):40–3. doi: 10.1159/000310574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larsson K, Lönnqvist B, Ringdén O, Hedquist B, Ljungman P. CMV retinitis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a report of five cases. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4(2):75–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2002.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee JJ, Teoh SC, Chua JL, Tien MC, Lim TH. Occurrence and reactivation of cytomegalovirus retinitis in systemic lupus erythematosus with normal CD4(+) counts. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(5):618–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Long HM, Dick A. Presumed CMV associated necrotizing retinopathy in a non-HIV immunocompromised host. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2005;33(3):330–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Margo CE, Arango JL. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and the lupus anticoagulant syndrome. Retina. 1998;18(6):568–70. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199806000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nasir MA, Jaffe GJ. Cytomegalovirus retinitis associated with Hodgkin's disease. Retina. 1996;16(4):324–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raz J, Aker M, Engelhard D, Ramu N, Or R, Cohen E, Nagler A, Benezra D. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in children following bone marrow transplantation. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 1993;1(3):263–8. doi: 10.3109/09273949309085027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott WJ, Giangiacomo J, Hodges KE. Accelerated cytomegalovirus retinitis secondary to immunosuppressive therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(8):1117–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050200023017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimakawa M, Kono C, Nagai T, Hori S, Tanabe K, Toma H. CMV retinitis after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2002;34(5):1790–2. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(02)03079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song WK, Min YH, Kim YR, Lee SC. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with alemtuzumab. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(10):1766–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tranos PG, Georgalas I, Founti P, Ladas I. Cytomegalovirus retinitis presenting as vasculitis in a patient with Wegener's granulomatosis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(4):961–3. doi: 10.2147/opth.s4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vote B, Russell M, Polkinghorne P. Recurrent cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with a normal lymphocyte count who had undergone splenectomy for lymphoma. Retina. 2005;25(2):220–1. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200502000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wimmersberger Y, Balaskas K, Gander M, Pournaras JA, Guex-Crosier Y. Immune recovery uveitis occurring after chemotherapy and ocular CMV infection in chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2011;228(4):358–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winkler A, Finan MJ, Pressly T, Roberts R. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in rheumatic disease: a case report. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(1):106–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis JL, Haft P, Hartley K. Retinal arteriolar occlusions due to cytomegalovirus retinitis in elderly patients without HIV. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1869-5760-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goldhardt R, Gregori NZ, Albini T, Yalamanchi S, Emanuelli A. Posterior subhyaloid precipitates in cytomegalovirus retinitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2012;2(1):41–5. doi: 10.1007/s12348-011-0032-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iwanaga M, Zaitsu M, Ishii E, Nishimura Y, Inada S, Yoshiki H, Okinami S, Hamasaki Y. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy and retinitis associated with cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent infant: a case report. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163(2):81–4. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1372-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kabata Y, Takahashi G, Tsuneoka H. Cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with valganciclovir in Wegener's granulomatosis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:521–3. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S31130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kelkar A, Kelkar J, Kelkar S, Bhirud S, Biswas J. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in a seronegative patient with systemic lupus erythematosus on immunosuppressive therapy. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2011;1(3):129–32. doi: 10.1007/s12348-010-0017-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Libby E, Movva S, Quintana D, Abdul-Jaleel M, Das A. Cytomegalovirus retinitis during chemotherapy with rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):e661–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oschman A, Murthy V, Kollipara R, Kenneth Lord R, Oluola O. Intravitreal ganciclovir for neonatal cytomegalovirus-associated retinitis: a case report. J Perinatol. 2013;33(4):329–31. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patel MP, Kute VB, Gumber MR, Shah PR, Patel HV, Dhananjay KL, Jain SH, Trivedi HL, Vanikar AV. Successful treatment of Nocardia pneumonia with cytomegalovirus retinitis coinfection in a renal transplant recipient. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(2):581–5. doi: 10.1007/s11255-011-0113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Piersigilli F, Catena G, De Gasperis MR, Lozzi S, Auriti C. Active retinitis in an infant with postnatally acquired cytomegalovirus infection. J Perinatol. 2012;32(7):559–62. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teh BW, Khot AS, Harrison SJ, Prince HM, Slavin MA. A messenger at the door: cytomegalovirus retinitis in myeloma patients with progressive disease. Transpl Infect Dis. 2013;15(4):E134–8. doi: 10.1111/tid.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Toriyama K, Suzuki T, Hara Y, Ohashi Y. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after multiple ocular surgeries in an immunocompetent patient. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2012;3(3):356–9. doi: 10.1159/000343705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tuncer S, Oray M, Yildirim Y, Camcioglu Y, Tugal-Tutkun I. Bilateral intraocular calcification in necrotizing cytomegalovirus retinitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Tzialla C, Decembrino L, Di Comite A, Bollani L, Colombo R, Stronati M. Colonic stricture and retinitis due to cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent infant. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(4):659–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sloan DJ, Taegtmeyer M, Pearce IA, Hart IJ, Miller AR, Beeching NJ. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in the absence of HIV or immunosuppression. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18(5):813–5. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Welling JD, Tarabishy AB, Christoforidis JB. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after central retinal vein occlusion in a patient on systemic immunosuppression: does venooclusive disease predispose to cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients already at risk? Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:601–3. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S28086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takakura, et al. Viral Retinitis following Intraocular or Periocular Corticosteroid Administration: A Case Series and Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Ocular Immunology & Inflammation. 2014, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Saidel M, Berreen J, Margolis T. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis After Intravitreous Triamcinolone in an Immunocompetent Patient. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1141–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Delyfer M-N, Rougier M-B, Hubschman J-P, Aouizérate F, Korobelnik J-F. Cytomegalovirus retinitis following intravitreal injection of triamcinolone: report of two cases. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2007;85(6):681–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Furukawa M. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis After IVTA treatment of a Vitrecotmized Eye in an Immunocompetent Patient. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports. 2007;1(4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Hsu J. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis After Treatment with Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide in an Immunocompetent Patient. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports. 2007;1(4):208–210. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e31802ea61c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ufret-Vincenty RL, Singh RP, Kaiser PK. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis after Fluocinolone Acetonide (Retisert) Implant. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:334–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Park YS, Byeon SH. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after intravitreous triamcinolone injection in a patient with central retinal vein occlusion. Korean J Ophthalmol . 2008;22(2):143–4. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2008.22.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sekiryu T, Iida T, Kaneko H, Saito M. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide in an immunocompetent patient. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2008;52(5):414–6. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Babiuch AS, Ravage ZB, Merrill PT. Cytomegalovirus Acute Retinal Necrosis in an Immunocompetent Patient After Sub-Tenon Triamcinolone Injection. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2010;4(4):364–365. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181b5ef2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shah AM, Oster SF, Freeman WR. Viral retinitis after intravitreal triamcinolone injection in patients with predisposing medical comorbidities. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Toyokawa N, Kimura H, Kuroda S. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis After Subtenon TA and Intravitreal Injection of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in an ImmunocompetentPatient with Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Diabetes Mellitus. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54(2):166–8. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tugal-Tutkun I, Araz B, Cagatay A. CMV retinitis after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection in a patient with Behçet’s uveitis. International Ophthalmology. 2010;30(5):591–3. doi: 10.1007/s10792-009-9332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vertes D, Snyers B, De Potter P. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after low-dose intravitreous triamcinolone acetonide in an immunocompetent patient: a warning for the widespread use of intravitreous corticosteroids. International Ophthalmology. 2010;30(5):595–7. doi: 10.1007/s10792-010-9404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zaborowski AG. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Following Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide in a Patient with Chronic Uveitis on Systemic Immunosuppression. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2013;(October):1–2 [DOI] [PubMed]