Abstract

Introduction

The analgesia nociception index (ANI) assesses the relative parasympathetic tone as a surrogate for antinociception/nociception balance in sedated patients. The aim of this study is to determine the effectiveness of ANI in detecting pain in deeply sedated critically ill patients.

Methods

This prospective observational study was performed in two medical ICUs. All patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation and deep sedation were eligible. In all patients, heart rate and ANI were continuously recorded using the Physiodoloris® device during 5 minutes at rest (T1), during a painful stimulus (T2), and during 5 minutes after the end of the painful stimulus (T3). The chosen painful stimulus was patient turning for washstand. Pain was evaluated at T2, using the behavioral pain scale (BPS). The primary objective was to determine the effectiveness of ANI in detecting pain. Secondary objectives included the impact of norepinephrine on the effectiveness of ANI in detecting pain, and the correlation between ANI and BPS.

Results

Forty-one patients were included. ANI was significantly lower at T2 (Med (IQR) 69(55–78)) compared with T1 (85(67–96), p<0.0001), or T3 (81(63–89), p<0.0001). Similar results were found in the subgroups of patients with (n = 21) or without (n = 20) norepinephrine. ANI values were significantly higher in patients with norepinephrine compared with those without norepinephrine at T1, and T2. No significant correlation was found between ANI and BPS at T2.

Conclusions

ANI is effective in detecting pain in deeply sedated critically ill patients, including those patients treated with norepinephrine. No significant correlation was found between ANI and BPS.

Introduction

Unfortunately, pain is still a frequent event in critically ill patients. Its incidence is difficult to assess, but at least 50% of surgical or medical patients experience pain during their ICU stay [1]. Chest tube removal, wound drain removal, arterial line insertion, and turning are the most painful procedures performed in the ICU [2]. Pain has a negative impact on patient outcome, and is associated with sleep disturbances, psychological stress and agitation [3]. Further, acute stress response, resulting from pain, includes neurovegetative system and neuroendocrine secretion dysfunctions [4,5].

Recent guidelines on the management of pain, agitation and delirium in adult patients recommend a systemic and rigorous evaluation of pain in critically ill patients, particularly because pain is consistently undertreated in this population [6]. Whilst evaluation of pain could be helpful in improving patient comfort and avoiding over sedation, this could be a difficult task in sedated non-communicative critically ill patients. Behavioral pain scale (BPS), and critical care pain observation tool (CPOT) provide acceptable levels of validity and reliability, and are recommended for nonverbal pain screening. However, these scores have some limitations, including the inter-rater variability, their impossible use in patients receiving neuromuscular-blocking agents, and the discontinuous assessment of pain [7]. In addition, these scores take into account only the physical component of the pain, and do not determine the level of anxiety and discomfort [8].

Analysis of heart rate variability (HRV) is a noninvasive method to evaluate autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. Heart rate (HR) low-frequency variations, between 0.04 and 0.15 Hz, are related to sympathetic and parasympathetic tones modulations. On the other hand, HR high-frequency variations, between 0.15 Hz and 0.4 Hz, are only related to the parasympathetic tone, which is mainly influenced by respiratory sinus arrhythmia [9,10]. As pain impacts ANS activity, HRV analysis provides a useful surrogate for pain evaluation. Previous studies have shown that pain, fear or anxiety reduce the parasympathetic activity, which can be measured as a decrease of HRV high-frequency spectrum [11–13].

The Analgesia Nociception Index (ANI) device (Physiodoloris®, MDoloris Medical Systems, Loos, France) allows noninvasive HRV analysis, by computing the ANI which is related to the parasympathetic activity of the patient [14,15]. Several studies have shown that this index reflects the parasympathetic response to noxious events during a painful stimulation [16–18]. However, to our knowledge no study has evaluated the effectiveness of ANI in evaluating pain in critically ill patients.

The primary aim of this prospective observational study is to evaluate the effectiveness of ANI in detecting pain in sedated, non-communicative, critically ill patients. The secondary aim was to evaluate the impact of norepinephrine use on ANI effectiveness, and to determine the correlation between ANI and BPS.

Patients and Methods

Settings and ethical aspects

This prospective observational study was conducted in two French medical ICUs (Lille University Hospital, and Victor Provo Hospital in Roubaix) during a 6-month period. The ethical committee of the Société de Réanimation de Langue Française approved the study (CE SRLF 11–239). The Institutional Review Board approved the study, and waived informed consent because of the non-interventional design. However, patients and/or their proxies were informed about the participation in this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All deeply sedated adult patients, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, and admitted to one of the two participating ICUs were eligible for this study. Exclusion criteria were light sedation, allowing communication with the patient; non-sinus cardiac rhythm; presence of pacemaker; atropine or isoprenaline treatment; and major cognitive impairment (massive stroke, resuscitated cardiac arrest).

ANI computation process

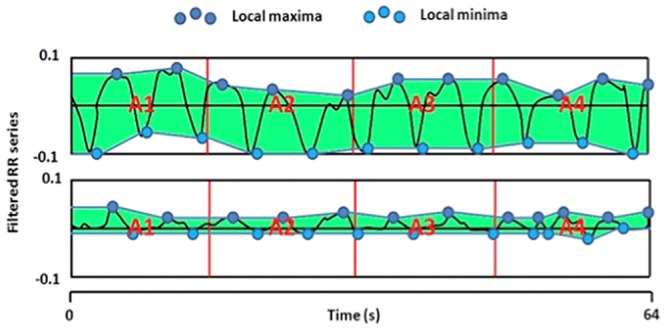

The ECG signal is acquired at a 250 Hz sampling rate, according to published recommendations [19]. ECG is then analyzed using an automatic R wave detection algorithm in order to obtain the R-R intervals time series. Erroneous R wave detection and ectopic beats are filtered using a non linear artifact removal algorithm [20] and filtered R-R series are re-sampled at a 8 Hz frequency using a linear interpolation as recommended [19]. The re-sampled R-R series are normalized in a 64 seconds moving window for inter subject comparability. Normalization process includes two steps. First, the mean value (M) is computed as:

where RRi represents the R-R samples values and N the number of samples in the window. M is then subtracted from each sample of the window as: RR’i = (RRi − M).

Second, the norm values (S) are computed as:

and each RR’i is divided by S: RR”i = RR’i / S.

The normalized RR” series are then high pass filtered between 0.15 and 0.5 Hz, using a 4 coefficient Daubeuchies wavelet based filter.

Local maximum and minimum are detected on this filtered signal and the lower and upper envelopes are plotted in order to compute the areas between envelopes A1, A2, A3 and A4 in four 16 seconds sub windows. AUCmin is detected as the minimum value of A1, A2, A3 and A4 and ANI is defined as: ANI = 100 x (a xAUCmin + b) / 12.8, where a = 5.1, and b = 1.2 values have been determined empirically in a dataset of more than 200 R-R series analysis, in order to keep the coherence between the visual effect of parasympathetic influence on RR series and the quantitative measurement of ANI (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Mean centered, normalized and band pass-filtered RR series in 2 different levels of pain: without any painful stimulus (upper panel), under painful stimulus (lower panel).

In clinical practice, ANI values close to 100 correspond to an important parasympathetic tone that can be associated to a high level of comfort. On the opposite, low ANI values are associated with a decreased parasympathetic tone, which is frequent in case of pain or anxiety.

Physiological data acquisition

The ANI was recorded using the Physiodoloris® monitor (MDoloris Medical Systems®, Loos, France). This monitoring device acquires the ECG signal through the analogical output of the patient’s multiparametric monitoring system, routinely used in the ICU and allowing a continuous display of ANI.

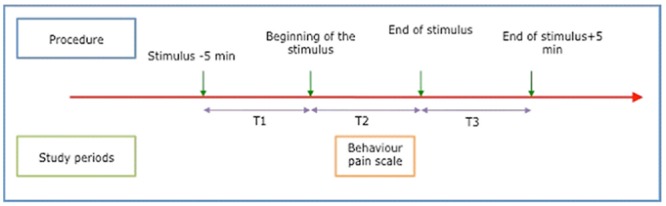

In all patients, HR and ANI were continuously recorded during 5 minutes at rest (T1), during a painful stimulus (T2), and during 5 minutes after the end of the painful stimulus (T3) (Fig 2). The stimulus we chose was the turning of the patient for washstand. Previous studies showed that patient turning was one of the most painful nursing procedures [21]. Each patient was his own control, and could only be included once in the study. Pain was assessed at T2 by the BPS [22]. In order to not influence the measurement of the BPS, nurses and physicians were blinded to the ANI monitor.

Fig 2. Time-points for ANI measurement.

Study population and clinical data

Sedation was performed based on a nurse-driven protocol. Propofol and remifentanil were used for patients requiring short-term (<72h) sedation. Midazolam, and sufentanil were used for long-term sedation (≥72h). ATICE score was calculated every three hours to determine the depth of sedation and adjust infusion rate, based on the prescription of the attending physician, and the written protocol.

The following data were collected for all study patients: Simplified Acute Physiology Score II, and Logistic Organ Dysfunction score at ICU admission, depth of sedation according to the ATICE scale [23].

Study Objectives

The primary objective was to demonstrate the effectiveness of ANI in detecting a painful stimulus in critically ill patients.

The secondary objectives were to determine the impact of norepinephrine on the effectiveness of ANI in detecting a painful stimulus, to evaluate the correlation between ANI and the BPS, and to determine factors associated with ANI during the painful stimulus.

Statistical analysis

The expected mean ANI at T1 and T2 was 70% (SD 20%), and 50% (expected difference of 20%); respectively. Considering a power of 90%, and an alpha risk of 5%, the inclusion of 20 patients was required.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 software. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Qualitative variables are presented as numbers (percentage). The distribution of continuous variables was tested, using Shapiro Wilk test. These data are presented as median (interquartile range), because of their skewed distribution. Wilcoxon non-parametric test was performed to compare ANI values before, during and after the painful stimulus. Chi square, or Fischer exact test, and Mann Whitney non parametric test was used to compare qualitative, and quantitative data between patients with and without norepinephrine; respectively.

The correlation between ANI and BPS was analyzed using a Spearman correlation rank test. Correlation between ANI and other quantitative, and qualitative factors was evaluated using Spearman, and Pearson correlations; respectively. All factors with p<0.1 were included in a multiple linear regression model, using ANI as a dependent variable.

Results

Patient characteristics

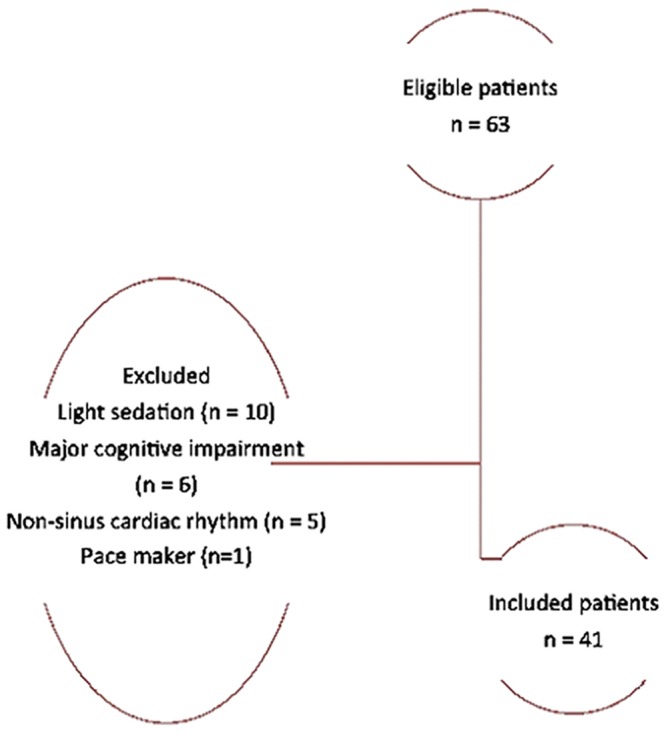

Forty-one patients were included, representing 65% of the 63 patients screened for eligibility. Twenty-two patients were excluded, including 10 for light sedation, 6 for major cognitive impairment, 5 for non-sinus cardiac rhythm, and 1 for pacemaker (Fig 3). Patient characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. At ICU admission, Age, SAPS II, LOD score, respiratory, and hemodynamic failure were significantly higher in patients with norepinephrine compared with those without norepinephrine (Table 1). At ANI measurement, LOD score, and percentage of patients with sufentanil were significantly higher in patients with norepinephrine compared with those without norepinephrine. ATICE score was significantly lower in patients with norepinephrine compared with those without norepinephrine.

Fig 3. Study flowchart.

Table 1. Patient characteristics at ICU admission.

| Norepinephrine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 20) | Yes (n = 21) | P value | |

| Age | 58 (48–62) | 70 (59–78) | 0.004 |

| SAPS II | 53(41–60) | 70 (56–79) | 0.001 |

| LOD score | 8 (4–9) | 10 (7–12) | 0.018 |

| Cause for ICU admission | |||

| Respiratory failure | 13 (65) | 6 (28) | 0.042* |

| Hemodynamic failure | 4 (2) | 17 (81) | <0.0001 |

| Neurologic failure | 4 (2) | 2 (9) | 0.410 |

| Others | 1 (5) | 3 (14) | 0.563 |

| Chronic comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 2 (10) | 6 (28) | 0.238 |

| COPD | 8 (40) | 4 (19) | 0.141 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2 (10) | 2 (9) | 1.000 |

| Cirrhosis | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1.000 |

SAPS, simplified acute physiology score; LOD, logistic organ dysfunction; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Some patients had more than one cause for ICU admission.

Data are numbers (percentage), or median (interquartile range).

*OR (95% CI)4.7 (1.2–1.7)

Table 2. Patient characteristics at inclusion.

| Norepinephrine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 20) | Yes (n = 21) | P value | |

| LOD score | 6 (3–8) | 10 (6–12) | 0.003 |

| ATICE E | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0.5–4) | 0.759 |

| ATICE C | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 0.929 |

| ATICE T | 10 (10–10) | 8 (7–10) | 0.003 |

| BPS | 5 (3–7) | 6 (3–8) | 0.277 |

| Neuromuscular blocking-agent use | 2 (10) | 2 (9) | >0.999 |

| Midazolam | 12 (60) | 15 (71) | 0.659 |

| Propofol | 4 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.103 |

| Sufentanil | 6 (30) | 15 (71) | 0.019* |

| Remifentanil | 11 (55) | 6 (28) | 0.162 |

LOD, logistic organ dysfunction; E, eyes; C, comprehension; T, tolerance; BPS, behavior pain scale

Data are numbers (percentage), or median (interquartile range).

*OR (95% CI)5.8(1.5–22)

Effectiveness of ANI in detecting painful stimulus

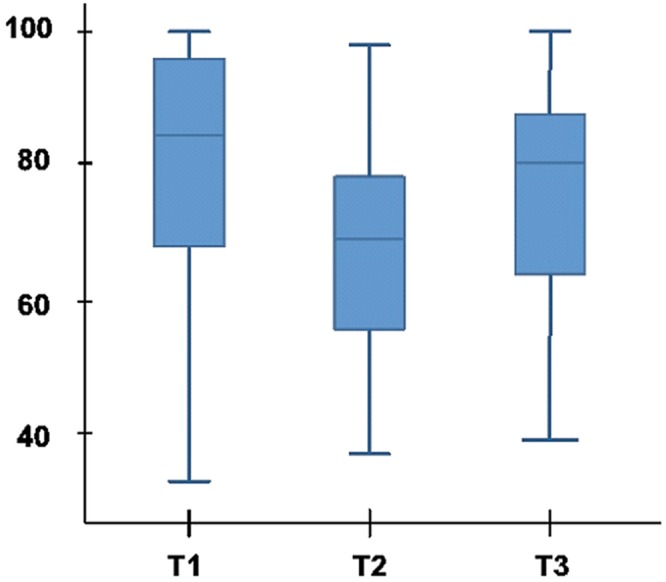

In all study patients, ANI was significantly lower at T2 (Med (IQR) 69(55–78)) than at T1 (85(67–96), p<0.0001), or T3 (81(63–89), p<0.0001) (Fig 4). No significant difference was found between ANI values obtained at T1, and T3.

Fig 4. ANI values in study patients.

In the subgroup of patients who did not receive norepinephrine (n = 20), ANI was significantly lower at T2 (57 (42–69)) than at T1 (74(66–80), p = 0.006), or T3 (68(53–88), p = 0.002).

In the subgroup of patients who received norepinephrine (n = 21), ANI was also significantly lower at T2 (75(66–80)) than at T1 (87(81–98), p = 0.001), or T3 (82(73–90), p = 0.023).

At T1 and T2, ANI values were significantly higher in the subgroup of patients who received norepinephrine, compared with those who did not receive norepinephrine. No significant difference was found in ANI values at T3 between these study subgroups (Table 3).

Table 3. ANI values in study subgroups.

| Norepinephrine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 20) | Yes (n = 21) | p | |

| ANI at T1 | 74 (53–94) | 87 (81–98) | 0.043 |

| ANI at T2 | 57 (42–69) | 75 (66–80) | 0.004 |

| ANI at T3 | 68 (53–88) | 82 (73–90) | 0.072 |

T1, T2, T3: before, during and after the painful stimulus; respectively.

Factors correlated with ANI during the painful stimulus

No significant correlation was found between ANI at T2 and BPS (p = 0.165, r2 = 0.221). In the subgroup of patients (n = 12) with BPS ≥ 7 (≥ 75th quartile), no significant correlation was found between ANI at T2 and BPS (p = 0.944). Age (r2 = 0.48, p = 0.001), SAPS II (r2 = 0.38, p = 0.012), and dose of norepinephrine (r2 = 0.50, p = 0.001) were significantly correlated with ANI. No significant (p>0.05) correlation was found between ANI and all other variables (LOD score, cause for ICU admission, chronic comorbidities, sedation level, and dose of sedation). Multiple linear regressions showed a significant correlation between ANI and age (r2 = 0.43, p = 0.036).

Discussion

Our results suggest that ANI is an effective tool to evaluate pain in deeply sedated critically ill patients. In addition, norepinephrine did not modify ANI effectiveness. However, no significant correlation was found between ANI and BPS.

Study strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate a simple device for pain assessment in deeply sedated critically ill patients. The Physiodoloris® device, used to assess ANI in this study, is totally noninvasive, easy to use, and compact. Using this device in the intensive care might be helpful to improve the quality of care, and reduce pain in critically ill patients.

However, some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, this study was observational, and included a small number of patients in two medical ICUs. Therefore, further large interventional studies are required to confirm our results in other populations, and to determine the value of this device in adjusting sedation level, improving patient comfort, and reducing unnecessary deep sedation. Second, the calculation of ANI is based on the respiratory sinus arrhythmia, which could be the result of pulmonary stretch receptors. However, several studies confirmed that this arrhythmia originated from the activity of bulbar respiratory centers [24]. Other studies evaluated whether mechanical ventilation, by reversing the intra-thoracic pressure regimen, reversed the respiratory sinus arrhythmia (i.e. induced a slowdown of cardiac frequency during insufflation). This was not confirmed, with important inter- and intra-individual variations, suggesting the importance of central nervous factors over mechanical influences [25]. However, in our study, each patient was used as its own control, which might have adjusted, at least in part, for these variations. Third, HRV might have occurred in response to the blood pressure variations, especially in patients with hemodynamic shock. However, these variations occur at low frequencies (basically 0,1 Hz), and are not taken into account in the ANI calculation. Fourth, ANI is a highly and quickly variable measure. For example, ANI falls immediately during the prick necessary for a capillary glycaemia, which is known to be a painful event. However, the continuous measurement of ANI allows clinicians to take its variability into account. Fifth, ANI was only evaluated during turning, and the impact of other painful procedures was not evaluated. However, turning critically ill mechanically ventilated patients is the most common nursing procedure in the ICU, and is one of the most painful procedures in these patients [2]. In fact, a recent study reported that pain defined as BPS score >3, or >5 was detected during turning in 94%, and in 64% of mechanically ventilated patients; respectively [26]. These results are in line with our findings, as median BPS value was 6 during tuning. Further, several previous studies clearly demonstrated the accuracy of ANI in detecting intraoperative, postoperative pain; as well as during labor, and experimentally induced pain [18,27–29]. Finally, ANI was evaluated only once per patient. However, it was recorded for 5 minutes during the painful stimulus, which might have allowed for brief variations in ANI values.

Impact of norepinephrine on ANI measurement

The subgroup analysis demonstrated that ANI was effective in detecting pain in patients receiving norepinephrine. ANI values before, and during the painful procedure were significantly higher in patients receiving norepinephrine, compared with those not receiving norepinephrine. Because norepinephrine is a sympathomimetic drug, a decreased parasympathetic tone and a decrease in ANI values were expected in patients receiving norepinephrine. However, an elegant clinical study showed that parasympathetic-tone decrease, in response to norepinephrine use, was not constant [30]. Moreover, several studies reported that severe sepsis interferes with HRV, resulting in a reduction of the low frequency / high frequency ratio (i.e., a change in ANS balance) indicating an increased parasympathetic activity. A positive correlation was also found between plasmatic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in septic patients, and the increase of the “high frequency” component of HRV, which is related to the parasympathetic tone measured by the ANI. Another potential explanation for this result is the significantly deeper sedation, as shown by the lower ATICE score in patients who received norepinephrine compared with those who did not receive norepinephrine.

Comparison of ANI with the BPS

We found no significant correlation between ANI and BPS. The recent clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit stated that both BPS, and CPOT demonstrated sufficient validity, and reliability to assess pain in critically ill patients, not able to communicate. One potential explanation for the absence of correlation between ANI and BPS is that ANI can detect painful events that do not result in modifications in the clinical signs included in this score. In other words, ANI is capable of detecting less intense pain. Absence of correlation can also be explained by the fact that ANI does not only measure pain, but also evaluates the neuropsychological dimension of pain, such as stress and discomfort. A recent study recorded ANI values in healthy volunteers before, during and after the display of a violent movie scene, considered as a negative emotional stimulus. The results showed a statistically significant decrease of ANI during the emotional stimulus [11]. Compared with the BPS, or to the CPOT, ANI has the advantage to be effective in paralyzed patients, and to provide instantaneous and continuous values. Moreover, this evaluation is totally objective, unlike all other available pain scales. Another potential explanation for the absence of significant correlation between ANI and BPS is the fact that patients were heavily sedated, suggesting that BPS values might not be accurate in this population. We performed a sensitivity analysis in only patients with high BPS score (≥75th quartile), and did not find a significant correlation between ANI and BPS. This result could be explained by the small number of patients in this subgroup (n = 12).

Conclusion

ANI is an effective tool to evaluate pain in deeply sedated critically ill patients. In addition, ANI is accurate for pain assessment in the subgroup of patients receiving norepinephrine. Measurement of ANI is a potentially interesting method to improve comfort in critically ill patients.

Abbreviations

- ANI

analgesia nociception index

- ANS

automatic nervous system

- BPS

behavioral pain scale

- CPOT

critical care pain observatory tool

- HR

heart rate

- HRV

heart rate variability

Data Availability

All data are available in the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1.Chanques G, Pohlman A, Kress JP, Molinari N, de Jong A, Jaber S et al. Psychometric comparison of three behavioural scales for the assessment of pain in critically ill patients unable to self-report. Crit Care 2014;18: R160 10.1186/cc14000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puntillo K, Max A, Timsit JF, Vignoud L, Chanques G, Robleda G et al. Determinants of procedural pain intensity in the intensive care unit: The Europain® study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189: 39–47. 10.1164/rccm.201306-1174OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaber S, Chanques G, Altairac C, Sebbane M, Vergne C, Perrigault PF et al. A prospective study of agitation in a medical-surgical ICU: Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Chest 2005;128: 2749–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page GG, Blakely WP, Ben-Eliyahu S. Evidence that postoperative pain is a mediator of the tumor-promoting effects of surgery in rats. Pain 2001;90: 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greisen J, Juhl CB, Grøfte T, Vilstrup H, Jensen TS, Schmitz O. Acute pain induces insulin resistance in humans. Anesthesiology 2001;95: 578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013;41: 263–306. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payen J-F, Gélinas C. Measuring pain in non-verbal critically ill patients: which pain instrument? Crit Care 2014;18: 554 10.1186/s13054-014-0554-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skrobik Y, Chanques G. The pain, agitation, and delirium practice guidelines for adult critically ill patients: a post-publication perspective. Ann Intensive Care 2013;3: 9 10.1186/2110-5820-3-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parati G, Mancia G, Di Rienzo M, Castiglioni P. Cardiovascular variability is/is not an index of autonomic control of circulation. J Appl Physiol 2006;101: 690–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miu AC, Heilman RM, Miclea M. Reduced heart rate variability and vagal tone in anxiety: Trait versus state, and the effects of autogenic training. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin 2009;145: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demaree H a., Robinson JL, Erik Everhart D, Schmeichel BJ. Resting RSA is associated with natural and self-regulated responses to negative emotional stimuli. Brain Cogn 2004;56: 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appelhans BM, Luecken LJ. Heart rate variability and pain: Associations of two interrelated homeostatic processes. Biol Psychol 2004;77: 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benarroch EE. Pain-autonomic interactions. Neurol Sci 2006;27: s130–s133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logier R, Jeanne M, De Jonckheere J, Dassonneville a, Delecroix M, Tavernier B. PhysioDoloris: a monitoring device for analgesia / nociception balance evaluation using heart rate variability analysis. Conference proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference. IEEE, Vol. 2010. pp. 1194–1197. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jeanne M, Clément C, De Jonckheere J, Logier R, Tavernier B. Variations of the analgesia nociception index during general anaesthesia for laparoscopic abdominal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput 2012;26: 289–294. 10.1007/s10877-012-9354-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabourdin N, Arnaout M, Louvet N, Guye ML, Piana F, Constant I. Pain monitoring in anesthetized children: First assessment of skin conductance and analgesia-nociception index at different infusion rates of remifentanil. Paediatr Anaesth 2013;23: 149–155. 10.1111/pan.12071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migeon A, Desgranges FP, Chassard D, Blaise BJ, De Queiroz M, Stewart A. Pupillary reflex dilatation and analgesia nociception index monitoring to assess the effectiveness of regional anesthesia in children anesthetised with sevoflurane. Paediatr Anaesth 2013;23: 1160–1165. 10.1111/pan.12243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boselli E, Daniela-Ionescu M, Bégou G, Bouvet L, Dabouz R, Magnin A, et al. Prospective observational study of the non-invasive assessment of immediate postoperative pain using the analgesia/nociception index (ANI). Br J Anaesth 2013;111: 453–459. 10.1093/bja/aet110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American society of pacing and electrophysiology, Circulation 1996;93: 1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logier R, De Jonckheere J, Dassonneville A. An efficient algorithm for R-R intervals series filtering. Conf Proc. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc Annu Conf 2004;6: 3937–3940. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Robleda G, Roche-Campo F, Urrútia G, Navarro M, Sendra M-À, Castillo A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of fentanyl in the pre-emptive treatment of pain associated with turning in patients under mechanical ventilation: research protocol. J Adv Nurs 2015;71: 441–450. 10.1111/jan.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, Lagrasta a, Novel E, Deschaux I, et al. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med 2001;29: 2258–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Jonghe B, Cook D, Griffith L, Appere-de-Vecchi C, Guyatt G, Théron V, et al. Adaptation to the Intensive Care Environment (ATICE): development and validation of a new sedation assessment instrument. Crit Care Med 2003;31: 2344–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benchetrit G. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia and voluntary control of breathing. Rev Mal Respir 2003;20: 978–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pumprla J, Howorka K, Groves D, Chester M, Nolan J. Functional assessment of heart rate variability: Physiological basis and practical applications. Int J Cardiol 2002;84: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robleda G, Roche-Campo F, Sendra M-À, Navarro M, Castillo A, Rodríguez-Arias A, et al. Fentanyl as pre-emptive treatment of pain associated with turning mechanically ventilated patients: a randomized controlled feasibility study. Intensive Care Med 2015; 10.1007/s00134-015-4112-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jess G, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Zahn PK, Meyer-Friessem CH. Monitoring heart rate variability to assess experimentally induced pain using the analgesia nociception index: A randomised volunteer study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015; 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeanne M, Delecroix M, De Jonckheere J, Keribedj A, Logier R, Tavernier B. Variations of the analgesia nociception index during propofol anesthesia for total knee replacement. Clin J Pain 2014;30: 1084–1088. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Guen M, Jeanne M, Sievert K, Al Moubarik M, Chazot T, Laloe PA et al. The Analgesia Nociception Index: a pilot study to evaluation of a new pain parameter during labor. Int J Obstet Anesth 2012;21: 146–151. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad S, Ramsay T, Huebsch L, Flanagan S, McDiarmid S, Batkin I, et al. Continuous multi-parameter heart rate variability analysis heralds onset of sepsis in adults. PLoS One 2009;4: e6642 10.1371/journal.pone.0006642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the paper.