Paediatric subspecialty education involves the state-of-the-art training and practice on specific scientific fields of Paediatrics requiring clinical expertising and academic excellence (1). The medical school settings and the tertiary hospitals have been specified as the main employment sites of paediatric subspecialists, where their major professional activities include direct paediatric patient care, teaching, as well as management duties. A combination of enhanced paediatric demands and expectations have contributed to the need for standardised and comprehensive training programmes, focusing on the suitable education of paediatric subspecialty trainees.

The paediatric infectious diseases subspeciality is one of the first subspecialities, which has been included in the paediatric training programmes in several countries, worldwide (2). To date, paediatric infectious diseases professionals have achieved a distinct role within the scientific field of Paediatrics and their contribution to tertiary paediatric care is considered invaluable (3,4). However, over the past decade, scientific advances on the field of Clinical Virology and Molecular Medicine have led to changes in current clinical practice as regards the management and treatment of neonates and children with viral infections. New viral infections are constantly emerging, requiring new prevention strategies and therapeutic protocols. Paediatric transplant infectious diseases are another challenge within paediatric infectious diseases, reflecting the complexity of this patient population (5). Moreover, new clinical practice guidelines for the vaccination of immunocompromised children have been established and thus regular reviewing of this matter is required (6). Additional scientific fields, including Evidence-based Medicine, Clinical Governance and Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamics (7) have also a significant supportive input. These advances have highlighted the role of Paediatric Virology as a new paediatric subspeciality candidate, a new unique challenging scientific area, where paediatric professionals of the 21st century require an advanced state-of-the-art education. The new challenges related to paediatric viral infections include emerging infections, opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients, antimicrobial resistance and the development of new diagnostic tests, vaccines and antiviral agents, ensuring the future of this paediatric subspecialty.

The word ‘Paediatric’, referring to the branch of Medicine that deals with the medical care of children, derives from two ancient Greek words: ‘παῖς’ (pais), which in modern Greek has changed to ‘παιδί’ (paidi), meaning the ‘child’ and ‘ἰατρός’ (iatros), meaning ‘the doctor’ or ‘the healer’, from the verb ‘ἰάομαι/ἰῶμαι’ (iaome/iome), meaning ‘healing’. On the other hand, the word ‘Virology’, the study of viruses, comes from the Latin word ‘virus’, meaning ‘the poison’, which has been in common use in the English language for many centuries and the ancient Greek word ‘λόγος’ (logos) from the verb ‘λέγω’, meaning ‘talk about’. The ancient Greek origin of virus, ‘ἰός’, comes from the verb ‘ἵημι’ (iimi), meaning ‘actuating, causing movement’, such as throwing an arrow or a poison. Both words in the term ‘Paediatric Virology’ contain the 9th letter of the Greek alphabet ‘ι’, the vertical line presented as an upright rod, an Homer's symbol of the strength of life. Of note, both actions of ‘ἰῶμαι’ supporting life and ‘ἵημι’ causing movement denote the strength and power that a children's healer needs in order to fight the small viral agents that pose a threat to the health and the life of children.

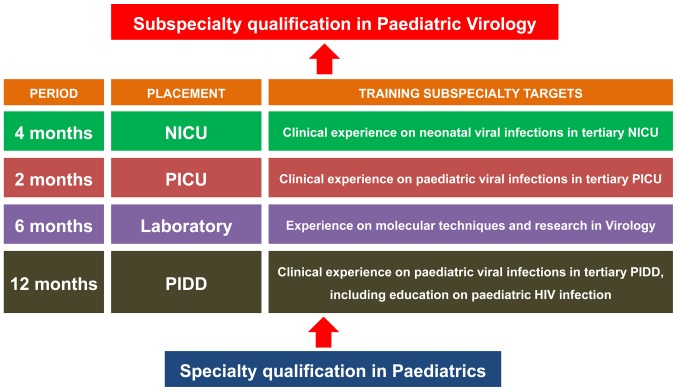

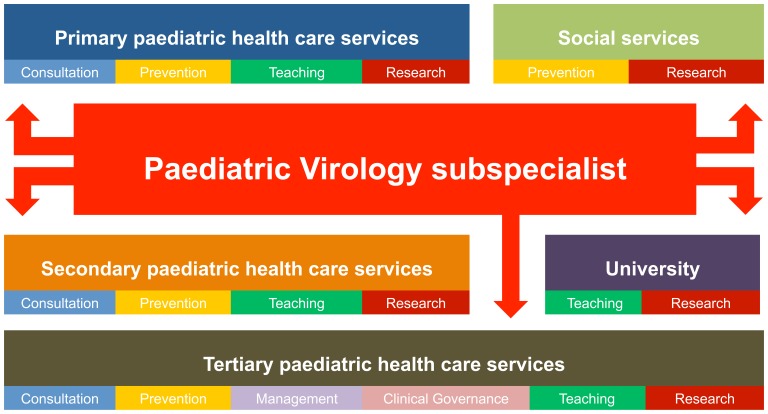

Paediatric trainees are proposed to play a leading role in this new subspeciality of Paediatrics, gaining valuable clinical and research experience on the prevention and management of viral infections in neonates and children (Fig. 1). They will be involved in the clinical care for hospitalised children with uncommon, recurrent, severe or complex neonatal and paediatric viral infections and will focus on their comprehensive assessment and treatment. Moreover, they will enhance the coordination of hospital and community care teams and offer appropriate consultation and assistance. After their qualification, Paediatric Virology subspecialists will play a multi-task role, not only in university-based research and educational settings, but also in primary, secondary and tertiary paediatric services (Fig. 2). Their increased accessibility can potentially result in cost savings to the health care system and better quality of care for paediatric patients. This will be achieved by limiting the unnecessary utilisation of emergency rooms, the multiple clinical visits to various health care providers and the request of unwarranted investigations.

Figure 1.

The proposed subspecialty training programme of Paediatric Virology. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NICU, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; PICU, Paediatric Intensive Care Unit; PIDD, Paediatric Infectious Diseases Department.

Figure 2.

The proposed multi-task role of Paediatric Virology subspecialists in primary, secondary and tertiary paediatric services, university-based research and educational settings.

It is important to determine whether and how Paediatric Virology as a new paediatric subspecialty can help paediatric clinical practice. In the present era of job limitations due to the financial crisis, it would be interesting to determine whether this subspecialty can support educational and academic strategies promoting current paediatric health and prevention. Without any doubt, our proposal requires further evaluation and discussion. The official recognition of Paediatric Virology by the key worldwide scientific and academic paediatric stakeholders will allow the development of an accredited training programme able to attract the highest quality paediatric trainees. In the future, Paediatric Virology subspecialists will be expected to have a strategically principal role, both clinical and academic, at the fight against viral infections in childhood. These efforts will aim to offer a state-of-the-art continuous medical education provided by both clinicians and basic scientists. This definitely needs more time, passion and inspiration.

References

- 1.Stoddard JJ, Cull WL, Jewett EA, Brotherton SE, Mulvey HJ, Alden ER. AAP Providing pediatric subspecialty care: A workforce analysis. AAP Committee on Pediatric Workforce Subcommittee on Subspecialty Workforce. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1325–1333. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noel GJ, Stavola JJ, Schauf V. Paediatric infectious diseases: A comprehensive guide to the subspecialty. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starr M. Paediatric infectious diseases: The last 50 years. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:12–15. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shulman ST. The history of pediatric infectious diseases. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:163–176. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000101756.93542.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danziger-Isakov L, Evans HM, Green M, McCulloch M, Michaels MG, Posfay-Barbe KM, Verma A, Allen U. ID CARE Committee from IPTA: Capacity building in pediatric transplant infectious diseases: an international perspective. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:790–793. doi: 10.1111/petr.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, Bousvaros A, Dhanireddy S, Sung L, Keyserling H, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:309–318. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker CI, Germovsek E, Hoare RL, Lestner JM, Lewis J, Standing JF. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling approaches in paediatric infectious diseases and immunology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;73:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]