Abstract

This study developed probabilistic models to describe Listeria monocytogenes growth responses in meat products with low concentrations of NaNO2 and NaCl. A five-strain mixture of L. monocytogenes was inoculated in NBYE (nutrient broth plus 0.6% yeast extract) supplemented with NaNO2 (0-141 ppm) and NaCl (0-1.75%). The inoculated samples were then stored under aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 4, 7, 10, 12, and 15℃ for up to 60 d. Growth response data [growth (1) or no growth (0)] for each combination were determined by turbidity. The growth response data were analyzed using logistic regression to predict the growth probability of L. monocytogenes as a function of NaNO2 and NaCl. The model performance was validated with the observed growth responses. The effect of an obvious NaNO2 and NaCl combination was not observed under aerobic storage condition, but the antimicrobial effect of NaNO2 on the inhibition of L. monocytogenes growth generally increased as NaCl concentration increased under anaerobic condition, especially at 7-10℃. A single application of NaNO2 or NaCl significantly (p<0.05) inhibited L. monocytogenes growth at 4-15℃, but the combination of NaNO2 or NaCl more effectively (p<0.05) inhibited L. monocytogenes growth than single application of either compound under anaerobic condition. Validation results showed 92% agreement between predicted and observed growth response data. These results indicate that the developed model is useful in predicting L. monocytogenes growth response at low concentrations of NaNO2 and NaCl, and the antilisterial effect of NaNO2 increased by NaCl under anaerobic condition.

Keywords: NaNO2, probabilistic model, L. monocytogenes, frankfurters

Introduction

L. monocytogenes are gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacteria with optimum temperatures of 30-35℃ (Faber and Peterkin, 1991; Hong et al., 2015). The pathogen is widely found in nature, and they can grow under stressful conditions such as refrigerated temperatures (5℃) and high concentrations of NaCl (10%) (Shin, 2009). In addition, the pathogens are found in many foods, especially in meat and processed meat products (Myersa, 2013; Pan et al., 2009). NaCl is used to improve the flavor and water holding capacity of processed meat products (Rhee and Zipirin, 2001), and to control bacterial growth in meat products (Aguilera and Karel, 1997). NaCl concentrations in meat products range from about 1.5% to 2.3% in South Korea (Kim et al., 2004).

NaNO2 is been known to paly a major role in coloring, controlling fat rancidity and controlling bacteria in meat products (Horsch et al., 2014). However, NaNO2 has chemical precursors that can be transformed into an N-nitroso compound under the low pH conditons of the stomach (Sugimura, 2000). This N-nitroso compound is reported to be toxic to the human body (Kemp and Dodds, 2002). Therefore, consumers preferentially purchase processed meat products with low NaNO2 concentrations as well as low NaCl concentrations, but microbial safety issues for these products have been raised (Sindelar et al., 2012).

Predictive models have been used to assess microbial behavior under various conditions. In particular, use of probabilistic models is appropriate for determining ideal concentration combinations of NaNO2 and NaCl for inhibiting the growth of foodborne pathogens in processed foods. A probabilistic model is developed with logistic regression analysis to produce interfaces between growth and no growth of bacteria under different environmental conditions (Jo et al., 2014; Koseki et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2012 ). Therefore, the objective of this study was to describe probabilistic models to predict L. monocytogenes growth responses in meat products formulated with low concentrations of NaNO2 and NaCl.

Materials and Methods

Inoculum preparation

L. monocytogenes NCCP (National Culture Collection for Pathogens) 10805 (poultry isolate), NCCP 10808 (human isolate), NCCP10809 (ruminant brain isolate), NCCP 10810 (human isolate) and NCCP10943 (rabbit isolate) were cultured in 10 mL nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract (NBYE; Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) at 30℃ for 24 h. The 0.1 mL aliquots of the cultures were then subcultured in fresh 10 mL NBYE at 30℃ for 24 h. The subcultures were centrifuged (1,912 g, 15 min, 4℃) and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4; 0.2 g of KH2PO4, 1.5 g of Na2HPO4·7H2O, 8.0 g of NaCl, and 0.2 g of KCl in 1 L distilled water). Suspensions of the five L. monocytogenes strains were mixed, and the mixture was serially diluted with PBS to obtain a density of 4 Log CFU/mL for inoculum.

Sample preparation and inoculation

The 225 μL of NBYE supplemented with combinations of NaNO2 (0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105, 120, and 141 ppm) and NaCl (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, and 1.75%) were placed into 96-well microtiter plates containing 25 μL aliquots of the prepared cell suspensions. Sterilized fresh NBYE and 225 μL fresh NBYE inoculated with 25 μL inoculum were used as negative control and positive control, respectively. The microtiter plates were stored under aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 4, 7, 10, 12, and 15℃ up to 60 d, depending on storage temperatures. For aerobic condition, the microtiter plates were sealed with Parafilm M® (Bemis Company Inc., USA), while the microtiterplates for anaerobic storage were sealed with Parafilm M® and placed into tightly closed plastic containers with Anaerogen pack (Oxoid Ltd., UK). The Anaerogen packs were replaced every day to maintain anaerobic condition.

Growth response and probabilistic model development

Growth or no growth for the combinations (NaNO2×NaCl×storage temperature×storage time; n=8) in aerobic and anaerobic conditions was determined every 24 h by turbidity of the samples. Turbid combinations were scored as 1 (growth) or 0 (no growth). The growth response data were analyzed by logistic regression using SAS® (Version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., USA) with the following equation to select significant parameters (p<0.05) with a stepwise selection method (Koutsoumanis et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2012). The selected parameters were then used to produce growth/no growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes at 0.1, 0.5 and 0.9.

Logit (P) = a0 + a1·NaCl + a2(NaNO2/10) + a3·Log(Time) + a4·Temp + a5·NaCl2 + a6·(NaNO2/10)2 + a7·Log(Time)2 + a8·Temp2 + a9·NaCl(NaNO2/10) + a10·NaCl·Log(Time) + a11(NaNO2/10)·Log(Time) + a12·Temp·NaCl + a12·Temp·(NaNO2/10) + a12·Temp·Log(Time)

Where logit (P) is an abbreviation for ln[P/(1−P)], ln is the natural logarithm, P is the probability of growth, ai are estimates, NaCl is the concentration of NaCl, NaNO2 is the NaNO2 concentration, Temp is the storage temperature, and Time is incubation time.

Validation

The performance of the developed probabilistic model was assessed by comparing the predicted growth data to the observed data obtained from frankfuters. To prepare frankfuters, pork meat (60%) and pork fat (20%) were mixed with ice water (20%), phosphate (0.3%), isolated soy protein (1.0%), mixed spice (0.5%), sugar (0.5%), potassium sorbate (0.2%), NaNO2 (0 and 10 ppm), and NaCl (1.0%, 1.25%, and 1.5%). The mixed pastes were then stored at 4℃ for 1 h and stuffed into 25-mm diameter collagen casing (#260, NIPPI Inc., Japan; approximate 25 mm diameter) using an automatic sausage can filler (Konti A50, Frey, Germany). The sausages were heated at 75℃ for 40 min in a smokehouse (MAXI 3501; Kerres, Germany) and then cooled at room temperature. The emulsion type sausage were then vacuum-packaged with polyethylene and heated at 80℃ for 15 min with subsequent cooling in ice water for 10 min. Frankfurters were stored at 4℃ until use (Choi et al., 2014). To inoculate L. monocytogenes on frankfurters, the vacuum-packages were opened, and 25 g portions of the samples were immersed into 500 mL L. monocytogenes inoculum (3 Log CFU/mL) in sterilized plastic containers for 2 min. The samples were air-dried under a laminar flow cabinet for 15 min, and the sausage were then transferred into sample bags. The samples were sealed for aerobic condition or vacuum-packaged for anaerobic conditon. The samples were incubated at 4℃, 10℃ and 15℃ for up to 1,416 h, 288 h, and 168 h, respectively. During storage, 40 mL 0.1% buffered peptone water (BPW; Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) was added into a sample bag and pummeled in a pummeler (BagMixer®, Interscience, France). The homogenates were serially diluted in BPW, and the diluents were spread-plated on PALCAM agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company) to enumerate L. monocytogenes. If the L. monocytogenes cell counts increased by more than 1 Log CFU/g compared to the initial cell counts, it was scored as “growth.” If the cell counts increased by less than 1 Log CFU/g, it was scored as “no growth” (Koutsoumanis et al., 2004). These results were then compared to the predicted growth response data from the developed probabilistic model; if the growth probability was greater than 0.5, it was determined as “growth” (Yoon et al., 2009).

Results and Discussion

The estimates for significant variables selected from the logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 1, and these estimates were used to produce the growth and no growth interfaces at probabilities of 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9. Under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, NaNO2 and NaCl showed significant effects on the inhibition of L. monocytogenes growth (Table 1). The models used the common logarithm of storage time due to its nonlinear effect on the end of the lag time (Koseki et al., 2012). NaNO2 concentration was divided by 10 to reduce statistical error by minimizing the difference between the observed values.

Table 1. Estimates of parameters selected from logistic regression analysis by a stepwise selection method to predict the interfaces between growth and no growth of L. monocytogenes at desired probabilities.

| Storage | Variables | Estimate | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Interception | −28.9018 | 0.2029 | <0.0001 |

| Temperature | 1.2925 | 0.0085 | <0.0001 | |

| NaNO2/10 | −0.4591 | 0.0033 | <0.0001 | |

| NaCl | 0.0704 | 0.0171 | <0.0001 | |

| Log (Time) | 8.0034 | 0.0567 | <0.0001 | |

| Anaerobic | Interception | −23.1749 | 0.1456 | <0.0001 |

| Temperature | 0.6829 | 0.0040 | <0.0001 | |

| NaNO2/10 | −0.5451 | 0.0030 | <0.0001 | |

| NaCl | 0.4213 | 0.0147 | <0.0001 | |

| Log (Time) | 7.4567 | 0.0463 | <0.0001 |

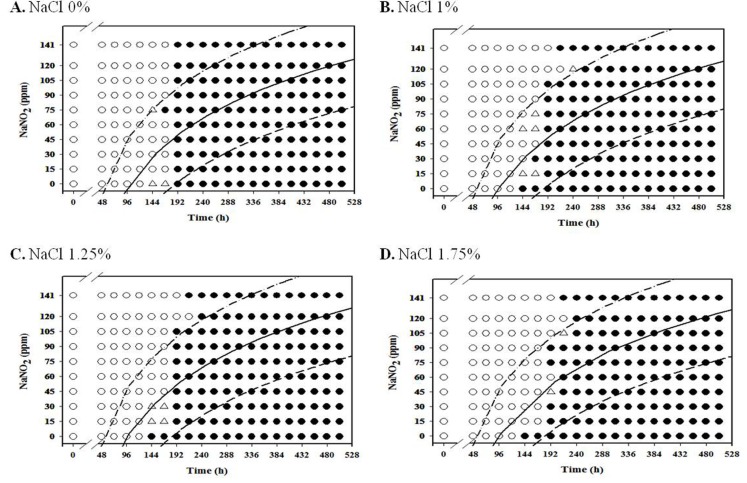

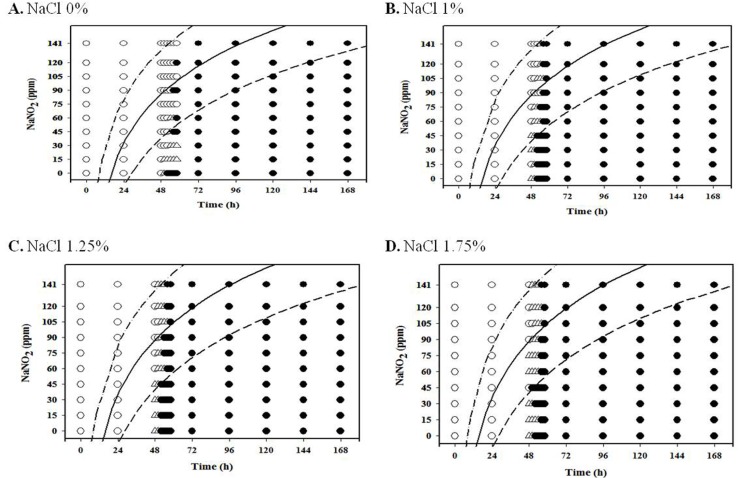

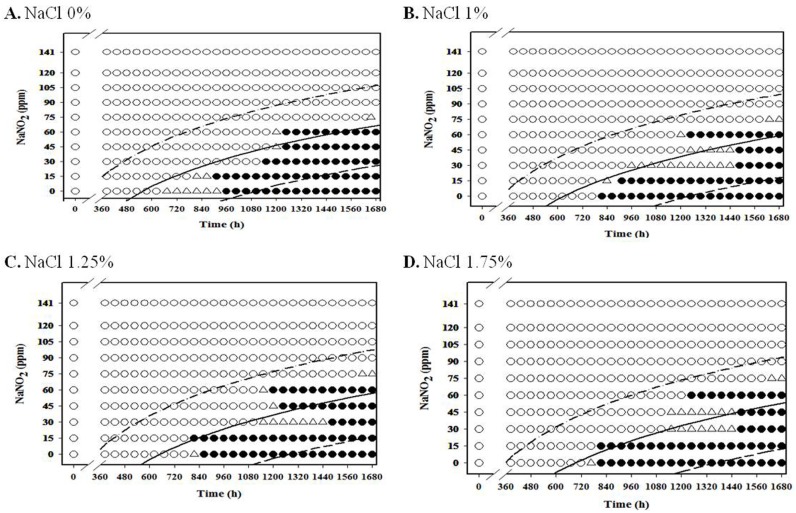

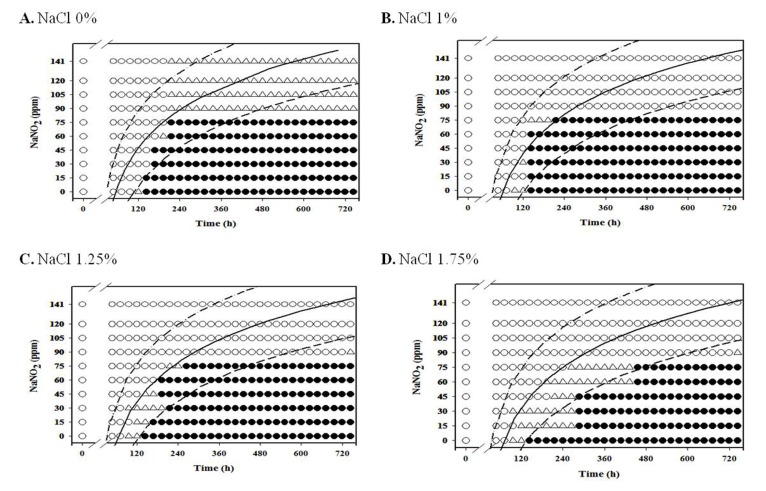

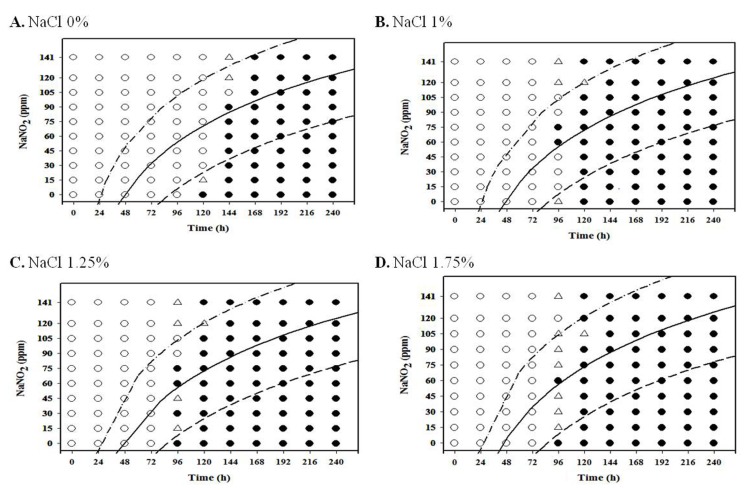

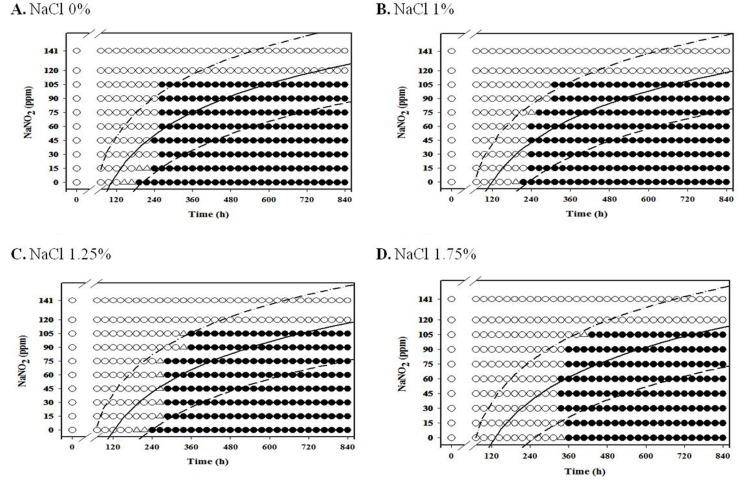

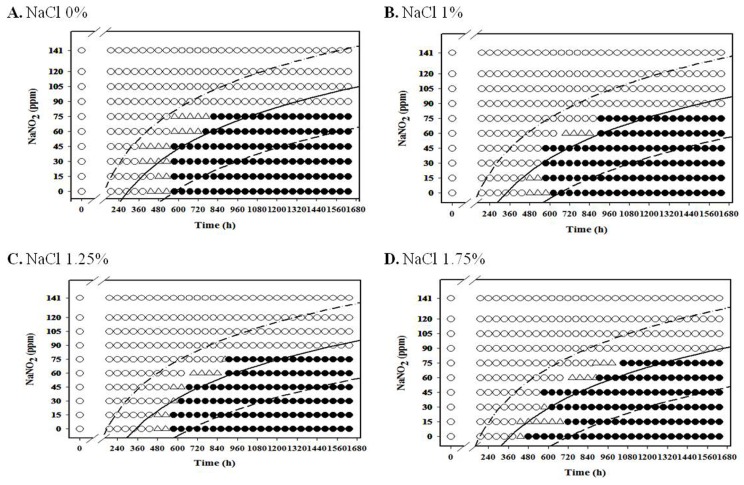

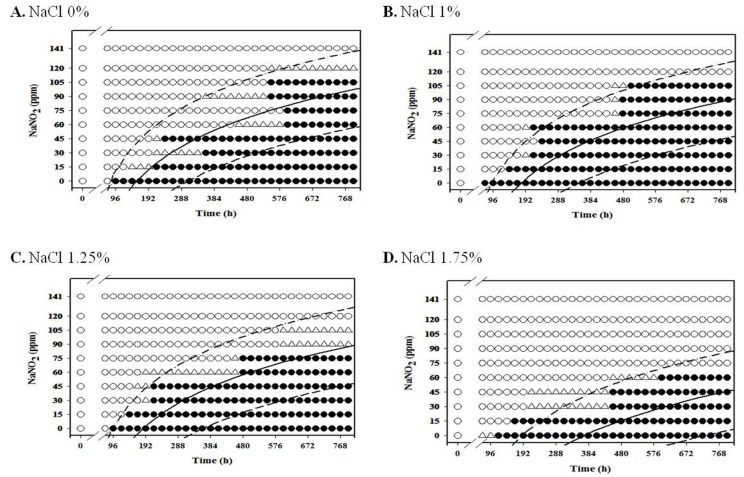

For aerobic storage condition, an obvious NaNO2 and NaCl combination effect was not observed (Fig. 1-3; data for 4℃ and 7℃ not shown), but the antimicrobial effect of NaNO2 on the inhibition of L. monocytogenes growth generally increased as NaCl concentration increased under anaerobic condition, especially at 7-10℃ (Fig. 4-8).

Fig. 1. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 10℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in aerobic condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

Fig. 3. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 15℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in aerobic condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

Fig. 4. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 4℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in vacuum condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

Fig. 8. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 15℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in vacuum condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

Fig. 2. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 12℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in aerobic condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

Fig. 7. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 12℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in vacuum condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

At 4℃ and 7℃, L. monocytogenes growth was not observed at 75 ppm NaNO2 or higher for all NaCl concentrations tested in this study under aerobic condition, and the pathogen initiated growth at 720-840 h for 4℃ and 480-600 h for 7℃ (data not shown). However, L. monocytogenes growth was generally observed at 10℃ after 192 h storage for all NaNO2 concentrations under aerobic storage (Fig. 1). Other studies have also reported that refrigeration storage and additives (NaCl and NaNO2) can cause stress to foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella (Laura et al., 2013; Pratt et al., 2012) and Escherichia coli (Jones et al., 2008), Clostridium botulinum (Derman et al., 2015). Thus, Laura et al. (2013) suggested that the effects of stressful conditions on bacteria are influenced by temperature because bacterial stress reponses were influenced by transcriptional changes at variant temperatures (Koutsoumanis et al., 2003). Ribeiro and Destro (2014) also studied that survival of two L. monocytogenes serotypes (1/2b and 4b) at high concentrations of NaCl and growth at refrigeration temperatures and found that environmental temperature may affect the virulence of the pathogens, thus temperature should be well controlled during food storage.

Certain countries allow a refrigeration temperature of up to 10℃ for retail market, and handmade sausages are usually displayed in aerobic packaging at retail. Our results suggest that NaNO2 should be present at a concentration of at least 75 ppm in order to inhibit L. monocytogenes growth in aerobic storage at 4℃ and 7℃, and processed meat product should be sold within 192 h in the event that the products are stored at 10℃.

For anaerobic condition, L. monocytogenes growth was inhibited at NaNO2 concentrations above 60 ppm for all NaCl concentrations under anaerobic condition at 4℃, and the growth of the pathogen was inhibited at NaNO2 concentrations about 75 ppm at 7℃ for all NaCl concentrations (Fig. 4 and 5). Under anaerobic storage at 4℃ and 7℃, the antimicrobial effect of NaNO2 on L. monocytogenes increased as NaCl concentration increased (Fig. 4 and 5). Interestingly, the observed growth inhibition concentrations (60-75 ppm) of NaNO2 were similar for both aerobic and anaerobic storage (Fig. 4 and 5; data not shown for aerobtic storage at 4℃ and 7℃), indicating that the inhibition effect of NaNO2 on L. monocytogenes may not be significantly influenced by oxygen concentration at 4℃ and 7℃ (Fig. 4 and 5). At 7℃ and 10℃, the combined effect of NaNO2 and NaCl on the inhibition of L. monocytogenes became very clear under anaerobic storage, indicating that the antilisterial effect of NaNO2 increased as NaCl concentration increased (Fig. 5 and 6). These results indicate that NaNO2 should be combined with NaCl to effectively inhibit the growth of L. monocytogenes in processed meat. In addition, the NaCl concentration should be higher than 1% for emulsion type sausage such as frankfurters in order to induce emulsion in sausage.

Fig. 5. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 7℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in vacuum condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

Fig. 6. Growth/no-growth interfaces of L. monocytogenes in nutrient broth with 0.6% yeast extract at 10℃ with respect to sodium nitrite concentration and storage time as a function of NaCl levels in vacuum condition at growth probabilities of 0.1 (left line), 0.5 (middle line), and 0.9 (right line); no growth: ○ , growth: ● , 50% growth: △ .

The performance of the developed model was assessed by a comparison between predicted and observed growth responses from the experiment with frankfurters. The predicted growth responses of the developed model were in agreement with most observed data under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The concordance percentage between observed and predicted growth responses was about 92% (data not shown).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the antilisterial effect of NaNO2 increased as NaCl concentration increased under anaerobic conditions, and the developed model should be useful in predicting the minimum concentrations of NaCl and NaNO2 combinations for the inhibition of L. monocytogenes growth in processed meat products formulated with low concentrations of NaNO2 and NaCl. Also, these results should be useful in quantitative microbial risk assessments.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (Project No. PJ009237)” Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Aguilera J. M., Karel M. Preservation of biological materials under desiccation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1997;37:287–309. doi: 10.1080/10408399709527776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi Y. S., Kim H. W., Hwang K. E., Song D. H., Choi J. H., Lee M. A., Chung H. J., Kim C. J. Physicochemical properties and sensory characteristics of reducedfat frankfurters with pork back fat replaced by dietary fiber extracted from makgeolli lees. Meat Sci. 2014;96:892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derman Y., Söderholm H., Lindström M., Korkeala H. Role of csp genes in NaCl, pH, and ethanol stress response and motility in Clostridium botulinum ATCC 3502. Food Microbiol. 2015;46:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farber J. M., Peterkin P. I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong Y. P., Choi J. W., Lee J. H., Yang R. Y. Combining of bacteriophage and G. asaii application to reduce L. monocytogenes on fresh-cut melon under low temperature and packing with functional film. J. Food Nut. Sci. 2015;3:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horsch A. M., Sebranek J. G., Dickson J. S., Niebuhr S. E., Larson E. M., Lavieri N. A., Ruther B. L., Wilson L. A. The effect of pH and nitrite concentration on the antimicrobial impact of celery juice concentrate compared with conventional sodium nitrite on Listeria monocytogenes. Meat Sci. 2014;96:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jo H., Park B. Y., Oh M. H., Gwak E., Lee H., Lee S., Yoon Y. Probabilistic models to predict the growth initiation time for Pseudomonas spp. in processed meats formulated with NaCl and NaNO2. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2014;34:736–741. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2014.34.6.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones T. H., Johns M. W., Gill C. O. Changes in the proteome of Escherichia coli during growth at 15℃ after incubation at 2, 6, or 8℃ for 4 days. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008;124:299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp M. J., Dodds W. K. The influence of ammonium, nitrate, and dissolved oxygen concentrations on uptake, nitrification, and denitrification rates associated with prairie stream substrata. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2002;47:1380–1393. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim I. S., Jin S. K., Hah K. H. Quality comparison of sausage and can products in Korean market. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2004;24:50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koseki S., Matsubara M., Yamamoto K. Prediction of a required log reduction with probability for Enterobacter sakazakii during high-pressure processing, using a survival/death interface model. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2009;75:1885–1891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02283-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koseki S., Nonaka J. Alternative approach to modeling bacterial lag time, using logistic regression as function of time, temperature, pH, and sodium chloride concentration. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2012;78:6103–6112. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01245-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koutsoumanis K. P., Kendal1 P. A., Sofos J. N. Effect of food processing-related stresses on acid tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2003;69:7514–7516. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7514-7516.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koutsoumanis K. P., Kendall P. A., Sofos J. N. Modeling the boundaries of growth of Salmonella Typhimurium in broth as a function of temperature, water activity, and pH. J. Food Prot. 2004;67:53–59. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laura P., Elena G., Mario G., Verónica A., Pedro R., Jose A. B. Survival of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella Enteritidis in sea bream (Sparus aurata) fillets packaged under enriched CO2 modified atmospheres. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;162:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J. Y., Suk H. J., Lee H., Lee S., Yoon Y. Application of probabilistic model to calculate probabilities of Escherichia coli O157:H7 growth on polyethylene cutting board. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2012;32:62–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myersa K., Cannon J., Montoya D., Dickson J., Lonergan S., Sebraneka J. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure and varying concentrations of sodium nitrite from traditional and vegetable-based sources on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes on ready-to-eat (RTE) sliced ham. Meat Sci. 2013;94:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan Y., Breidt F., Kathariou S. Competition of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2a and 4b strains in mixed-culture biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2009;75:5846–5872. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00816-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratt Z. L., Chen B., Czuprynski C. J., Wong A. C. L., Kaspar C. W. Characterization of osmotically induced filaments of Salmonella enterica. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2012;78:6704–6713. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01784-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee K. S., Zipirin Y. A. Pro-oxidative effects of NaCl in microbial growth-controlled and uncontrolled beef and chicken. Meat Sci. 2001;57:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1740(00)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribeiro V. B., Destro M. T. Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2b and 4b isolates from human clinical cases and foods show differences in tolerance to refrigeration and salt stress. J. Food Prot. 2014;9:1448–1648. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin J. H. Comparison of the σB-dependent general stress response between Bacillus subtilis and Listeria monocytogenes. Kor. J. Microbiol. 2009;45:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sindelar J. J., Milkowski A. L. Human safety controversies surrounding nitrate and nitrite in the diet. Nitric Oxide. 2012;26:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimura T. Nutrition and dietary carcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:387–395. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon H., Lee J. Y., Suk H. J., Lee S., Lee H., Lee S., Yoon Y. Modeling to predict growth/no growth boundaries and kinetic behavior of Salmonella on cutting board surfaces. J. Food Prot. 2012;75:2116–2121. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon Y., Kendall P. A., Belk K. E., Scanga J. A., Smith G. C., Sofos J. N. Modeling the growth/no growth boundaries of postprocessing Listeria monocytogenes contamination on frankfurters and bologna treated with lactic acid. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2009;75:353–358. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00640-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]