Abstract

The design, synthesis, and validation of new highly effective bifunctional linchpins for type II anion relay chemistry (ARC) has been achieved. The mechanistically novel negative-charge migration that comprises the Brook rearrangement is now initiated by a stabilized tetrahedral intermediate, which is generated by nucleophilic addition to a Weinreb amide, rather than by a simple oxyanion that is generated from an epoxide. As a result, the linchpin preserves the carbonyl functionality in the ARC adducts, thus permitting access to functionally complex systems in a single flask without the need for further chemical manipulations. This tactic was validated with the one-pot preparation of monoprotected 1,3-diketones as well as pyran and spiroketal scaffolds, depending on the choice of nucleophile, electrophile, and work-up conditions.

Keywords: anion relay chemistry; Brook rearrangement; 1,3-diketones; spiroketals; Weinreb amides

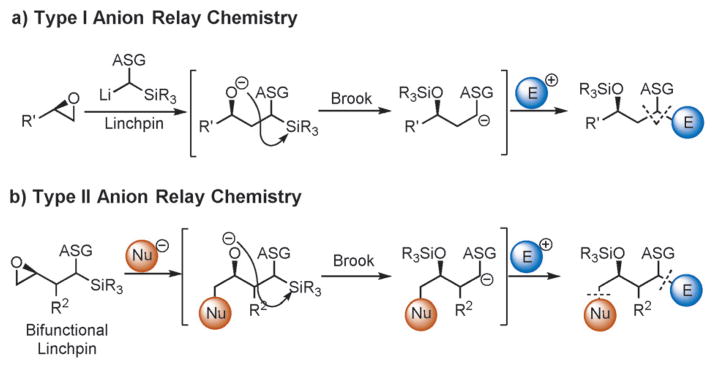

In an attempt to mimic Nature’s elegant synthesis of complex molecules, the concept of anion relay chemistry (ARC) has been developed and validated as a versatile synthetic plat-form for the union of complex fragments to furnish multi-component adducts in an effective and stereocontrolled fashion.[1] ARC methods can be categorized based on the nature of the negative-charge migration: “Through-bond” ARC (e.g., conjugate addition) has been widely exploited in organic chemistry, whereas “through-space” ARC has come to fruition only over the past two decades. Our interests in this area focus on the development and implementation of “through-space” ARC, which can be subdivided into type I and type II tactics. Type I ARC was developed based on the precedent set by the groups of Matsuda and Tietze,[2] wherein linchpins react with 2 equivalents of an epoxide to furnish symmetric tricomponent adducts. Later, by controlling the timing of the Brook rearrangement through a change in solvent polarity, counterion, or temperature, the formation of unsymmetric tricomponent adducts was achieved, thus increasing the utility of the tactic for complex-molecule synthesis (Scheme 1a).[3] Subsequently, we designed and validated the type II ARC tactic, which involves charge migration across a bifunctional linchpin, again through a controlled Brook rearrangement, resulting in a distinct class of tricomponent adducts (Scheme 1b).[4]

Scheme 1.

a) Type I and b) type II anion relay chemistry. ASG =anion-stabilizing group.

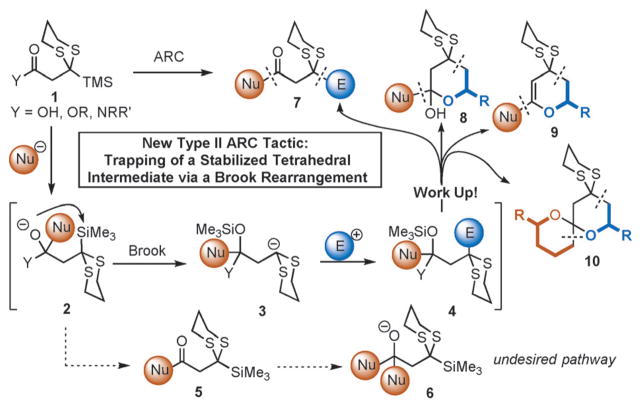

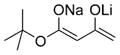

Whereas both the type I and II ARC tactics have been exploited in a number of total synthetic ventures in our laboratory,[5] we have continued to design and validate new ARC linchpins. To this end, we envisioned a new class of type II linchpins that would permit access to multicomponent adducts bearing monoprotected 1,3-dicarbonyl functional groups by means of a mechanistically new ARC tactic. Specifically, we turned to the introduction of a carboxylic acid derivative at the electrophilic terminus of the linchpin (1; Scheme 2), reasoning that the relative stability of the derived tetrahedral intermediate resulting from nucleophilic addition (see 2; Scheme 2) would permit the desired Brook rearrangement to outcompete premature collapse to the ketone (5), thereby preventing over-addition of the initiating nucleophile. If effective, the Brook rearrangement would reveal a nucleophilic carbanion, which in turn could add to an electrophile and thereby construct a multicomponent adduct (Scheme 2). Although precedent can be found for the capture of a tetrahedral intermediate by N-to-O and S-to-O silyl migrations,[6] the potential for premature collapse of the tetrahedral intermediate in the polar medium typically required to trigger the Brook rearrangement (i.e., C-to-O silyl group migration) would have to be overcome to realize our goal.

Scheme 2.

Type II anion relay chemistry linchpin: a new concept.

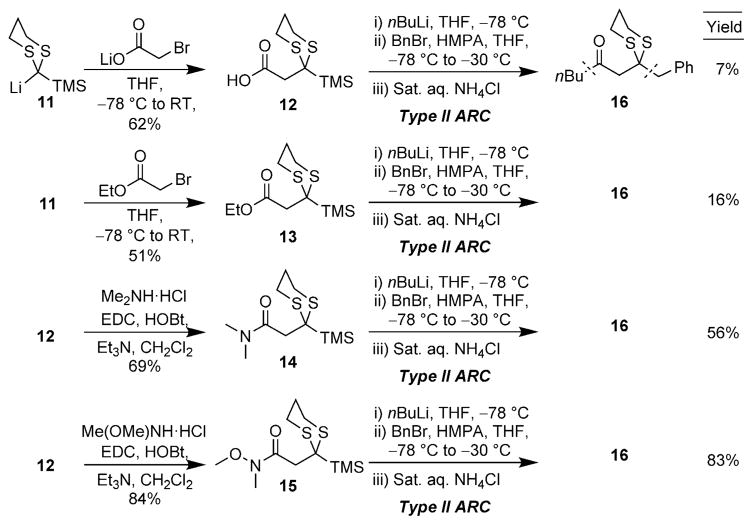

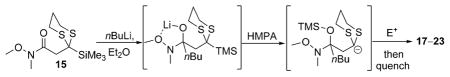

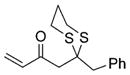

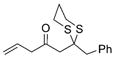

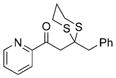

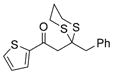

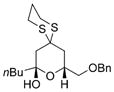

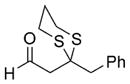

To explore the envisioned new ARC tactic, we first constructed the prospective linchpins 12–15 (Scheme 3). Carboxylic acid 12 and ethyl ester 13 were prepared in analogous fashion, namely by nucleophilic addition of TMS-dithiane to lithium bromoacetate and ethyl bromoacetate, respectively.[7] In turn, amide coupling of 12 with the HCl salts of N,N-dimethylamine and N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine provided amide linchpins 14 and 15; the latter compound is a Weinreb amide (Scheme 3).[8] With the first linchpins 12 and 13 in hand, the feasibility of the proposed ARC tactic was explored in THF at –78° C, using n-butyl lithium (nBuLi) as the nucleophile and benzyl bromide (BnBr) as the electrophile; hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) was employed to trigger the Brook rearrangement. Unfortunately, the reaction sequence resulted in the formation of complex mixtures, with only minor amounts of the desired product 16 (<16%). Pleasingly, however, when 14 and 15 were subjected to the aforementioned reaction conditions, the desired product 16 could be isolated in good to excellent yield after protic workup and flash chromatography. The superiority of the Weinreb amide linchpin 15, relative to congener 14, suggests that the stabilization of the tetrahedral intermediate imparted by the N-methoxy moiety, presumably by chelation of lithium, prevents premature Brook rearrangement and is pivotal to the success of this ARC tactic.[8]

Scheme 3.

Linchpin synthesis and preliminary studies.

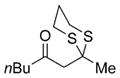

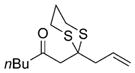

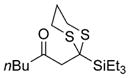

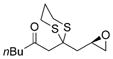

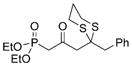

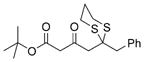

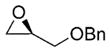

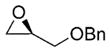

Excited by the initial results, we proceeded to analyze the scope and utility of this new ARC tactic with linchpin 15 and diverse electrophiles and nucleophiles (Tables 1 and 2). Pleasingly, the ARC reactions proceeded smoothly in good yield with methyl iodide and allyl bromide (entries 1 and 2, Table 1), whereas the yields achieved with homoallylic, alkynyl, and alkyl bromides were somewhat lower than with the corresponding iodide congeners (entries 3–5). The reaction with chlorotriethylsilane also proceeded effectively to provide adduct 22 in 71% yield. Finally, when epichlorohydrin was employed as the terminating electrophile, epoxide 23 was obtained in good yield, resulting as expected from nucleophilic attack at the terminal epoxide carbon atom rather than direct displacement of the chloride.[9]

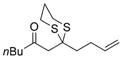

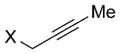

Table 1.

Electrophile scope with linchpin 15.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | E+ | Product | Yield |

| 1 | Mel |

17 |

78% |

| 2 |

|

18 |

75% |

| 3 |

a)X=Br b)X=1 |

19 |

a) 59% b) 74% |

| 4 |

a)X=Br b)X=1 |

20 |

a) 52% b) 67% |

| 5 |

a)X=Br b)X=1 |

21 |

a) 55% b) 69% |

| 6 | Et3SiCl |

22 |

71% |

| 7 |

(R)-epichiorohydrin |

(R)-23 |

60% |

Reaction conditions: i) 15, THF, –78° C, then slow addition of nBuLi; ii) electrophile, HMPA, THF, –78° C to –30° C; iii) sat. aq. NH4Cl.

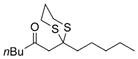

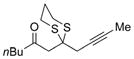

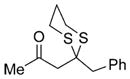

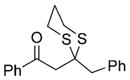

Table 2.

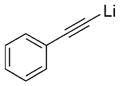

Nucleophile scope with linchpin 15.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | NuLi | Product | Yield |

| 1 | MeLi |

24 |

78% |

| 2 |

|

25 |

71% |

| 3 |

|

26 |

53% |

| 4 |

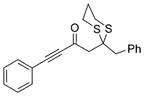

|

27 |

66% |

| 5 |

|

28 |

74% |

| 6 |

|

29 |

71% |

| 7 |

|

(R)-30 |

59% |

| 8 |

|

(R)-31 |

68%[b] |

| 9 |

|

(R)-32 |

63%[b] |

| 10 |

|

(R)-33 |

64%[b] |

Reaction conditions: i) 15, THF, –78° C, then slow addition of NuLi; ii) BnBr, HMPA, THF, –78° C to –30° C; iii) sat. aq. NH4Cl.

i) 15, THF,–78 ° C, then slow addition of NuLi; ii) BnBr, THF, then slow addition of HMPA/THF solution, –78° C to –30° C; iii) sat. aq. NH4Cl.

Next, we explored the nature of the nucleophilic component of the ARC reaction, employing benzyl bromide as the electrophilic species (Table 2). Again, the ARC reactions proceeded in good yield with alkyl, alkenyl, alkynyl, allyl, and aryl lithium nucleophiles (entries 1–7). The addition of softer nucleophiles was also explored (entries 8–10). To achieve these transformations, greater control over the timing of the Brook rearrangement was required: Key to success was the addition of a solution of benzyl bromide in THF to the tetrahedral intermediate, followed by the slow addition of a precooled HMPA/THF solution. With this procedure, the reactions furnished the desired tricomponent adducts in generally good yields.

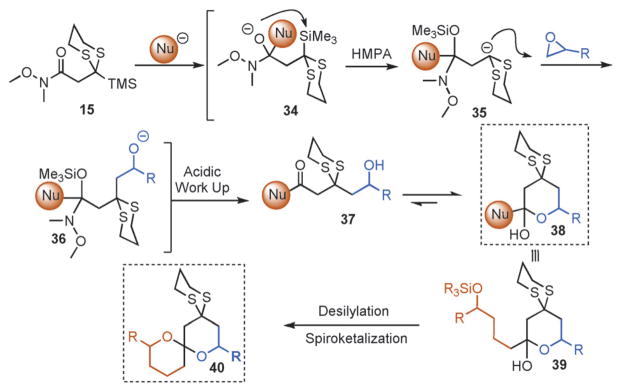

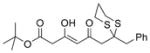

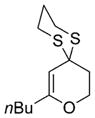

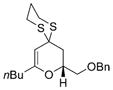

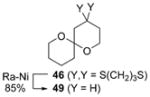

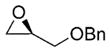

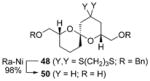

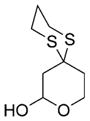

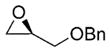

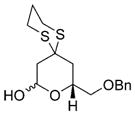

To demonstrate the utility of the monoprotected 1,3-diketone motif that is now readily accessible by this ARC tactic, we studied the one-pot construction of substituted pyran and spiroketal scaffolds from structurally simple components (Scheme 4).[10] Initial attempts at the single-flask ARC cyclization method entailed use of nBuLi as the initiating nucleophile with ethylene oxide as the terminating electrophile; 41 was isolated in good yield after protic workup and chromatography (entry 1, Table 3). Use of (R)-benzyl glycidyl ether as the terminating electrophile led to lactol 42 also in good yield, whereas simply altering the workup procedure (i.e., more acidic conditions; quench B, Table 3) led to dihydropyran 43. Next, an alkyl lithium reagent bearing a terminal TBS ether, which was envisioned to undergo in situ deprotection, was employed as the initiating nucleophile with benzyl bromide as the terminating electrophile. Upon reaction completion (determined by TLC), addition of aqueous HF furnished 45 in 60% yield. Similarly, the use of ethylene oxide resulted in the formation of spiroketal 46. Turning to nucleophile 47 and (R)-benzyl glycidyl ether as the electrophile, followed by silyl group removal, led to spiroketal 48 in 67% yield. Treatment of 46 and 48 with Raney nickel under a hydrogen atmosphere furnished (–)-olean (49) and SPIKET-P (50) respectively.[11,12]

Scheme 4.

Proposed preparation of cyclic compounds.

Table 3.

Preparation of cyclic systems utilizing 15.[a]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | NuLi | E+ | Quench | Product | Yield |

| 1 | nBuLi |

|

A |

41 |

68% |

| 2 | nBuLi |

|

A |

42 |

69% |

| 3 | nBuLi |

|

B |

43 |

72% |

| 4 |

44 |

BnBr | B |

45 |

60% |

| 5 |

44 |

|

B |

|

64% |

| 6 |

47 |

|

B |

|

67% |

Reaction conditions: i) 15, Et2O, –78 ° C, then slow addition of NuLi; ii) BnBr, HMPA, Et2O, –78 ° C to –30° C; iii) quench A with sat. aq. NH4Cl or quench B with 48 % aq. HF, then NaHCO3.

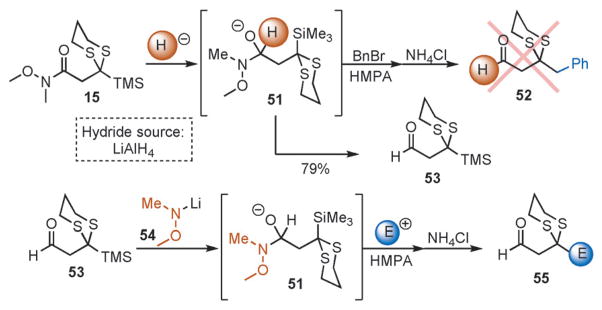

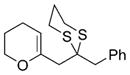

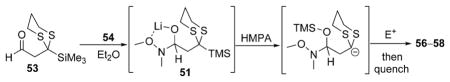

Finally, we have also achieved the construction of complex aldehydes in a similar manner to that presented for the preparation of tricomponent ketones and ketals. Treatment of 15 with a nucleophilic hydride (LiAlH4) and subsequent addition of BnBr in a HMPA/THF solution did not result in the formation of the envisioned adduct (Scheme 5, 52). Whereas this was not the desired outcome, we envisioned that the addition of lithium N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine 54 to 53 would permit formation of intermediate 51;[13] subsequent Brook rearrangement, electrophile addition, and protic work up would then yield adduct 55. Gratifyingly, addition of 54 to 53 followed by a solution of benzyl bromide in HMPA/Et2O and protic workup provided aldehyde 56 in 78% yield (Table 4, entry 1). In similar fashion, use of ethylene oxide and (R)-benzyl glycidyl ether as the terminating electrophiles permitted the preparation of 57 and 58 in good yields (entries 2 and 3).

Scheme 5.

Preparation of aldehydecontaining adducts.

Table 4.

Application of aldehyde linchpin 51.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | E+ | Product | Yield |

| 1 | BnBr |

56 |

78% |

| 2 |

|

57 |

65% |

| 3 |

|

58 |

68% |

Reaction conditions: i) 51, Et2O, –78 ° C, then slow addition of NuLi; ii) BnBr, HMPA, Et2O, –78 ° C to –30° C; iii) sat. aq. NH4Cl.

In summary, we have designed, synthesized, and validated Weinreb amide 15 as a new type II ARC linchpin for the efficient preparation of architecturally complex scaffolds. This linchpin showcases a novel ARC tactic that permits the ready construction of differentiated 1,3-diketones and derivatives while circumventing the requirement for protecting-group and oxidation-state manipulations. In turn, we have illustrated the utility of this new ARC linchpin, most notably in the preparation of di- and tetrahydropyrans as well as spiroketals in one-pot processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIH (GM-29028). We thank Dr. G. Furst and Dr. R. Kohli at the University of Pennsylvania for assistance in obtaining NMR and high-resolution mass spectra, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201509342.

References

- 1.Smith AB, III, Wuest WM. Chem Commun. 2008:5883–5895. doi: 10.1039/b810394a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Matsuda I, Murata S, Ishii Y. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1979:26–30. [Google Scholar]; b) Tietze LF, Geissler H, Gewert JA, Jakobi U. Synlett. 1994:511–512. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Shinokubo H, Miura K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:503–514. [Google Scholar]; b) Shinokubo H, Miura K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1951–1954. [Google Scholar]; c) Smith AB, III, Boldi AM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6925– 6926. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AB, III, Xian M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:66–67. doi: 10.1021/ja057059w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Smith AB, III, Tomioka T, Risatti CA, Sperry JB, Sfouggatakis C. Org Lett. 2008;10:4359–4362. doi: 10.1021/ol801792k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Smith AB, III, Kim D-S. J Org Chem. 2006;71:2547–2557. doi: 10.1021/jo052314g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Smith AB, III, Kim D-S. Org Lett. 2005;7:3247–3250. doi: 10.1021/ol0510264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Melillo B, Smith AB., III Org Lett. 2013;15:2282–2285. doi: 10.1021/ol400857k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Han H, Smith AB., III Org Lett. 2015;17:4232– 4235. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Adams JL, Chen TM, Metcalf BW. J Org Chem. 1985;50:2730–2736. [Google Scholar]; Sun X, Song Z, Li H, Sun C. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:17589–17594. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cer7 V, De Angelis S, Pollicino S, Ricci A, Reddy CK, Knochel P, Cahiez G. Synthesis. 1997:1174–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahm S, Weinreb SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:3815–3818. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClure DE, Arison BH, Baldwin JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:3666–3668. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Such scaffolds are ubiquitous in bioactive natural products; see: Zampella A, D’Auria MV, Minale L, Debitus C, Roussakis C. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11085–11088.Pettit GR, Gao F, Blumberg PM, Herald CL, Coll JC, Kamano Y, Lewin NE, Schmidt JM, Chapuis JC. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:286–289. doi: 10.1021/np960100b.Kwon HC, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 2009;74:675– 684. doi: 10.1021/jo801944d.

- 11.Baker R, Herbert RH. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1987:1123–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang H, Mao C, Jan S-T, Uckun FM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1699–1702. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comins DL, Brown JD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4213–4216. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.