Abstract

Myeloid tumor possessing platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) gene rearrangement is a rare hematological malignancy, which presents with typical characteristics of myeloid proliferation disorders and eosinophilia. In the present study, an elderly chronic myelomonocytic leukemia patient was diagnosed with chromosome rearrangement. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was conducted with a PDGFRβ isolate probe, and gene translocation between PDGFRβ on chromosome 5 and genes on the chromosomes of group D (13–15) was detected. Karyotype analysis revealed a chromosome 5 break, and PDGFRβ-thyroid hormone receptor interactor 11 (CEV14) gene fusion was confirmed via reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which additionally revealed the chromosome rearrangement t(5;14)(q33;q32). Due to the correlation between PDGFRβ-CEV14 expression and effectiveness of treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, this fusion gene is considered to be an oncogene. In the present study, an elderly patient was diagnosed with a myeloid tumor associated with the fusion gene PDGFRβ-CEV14, using the methods of FISH and RT-PCR. These methods were confirmed to be of significant value in improving diagnosis, guiding treatment and increasing the cure rate of patients, due to their ability to detect multiple rearrangement genes associated with PDGFRβ in myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Keywords: chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, chromosome rearrangement, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β, gene fusion

Introduction

Platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs), which are part of the class III receptor tyrosine kinase family, exert stimulatory effects on c-Kit, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptors (1). PDGFRs consist of an extracellular ligand-binding region, a transmembrane domain and an intracellular kinase domain (2). Ligand binding induces dimerization and autophosphorylation of the receptor, facilitating binding and activation of various cytoplasmic signal transduction molecules (3). In this way, multiple signaling pathways are initiated, resulting in cell proliferation (4).

Myeloid tumors possessing PDGFRβ gene rearrangement are a rare hematological malignancy, which present with typical characteristics, including myeloid proliferation disorders and eosinophilia. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a poorly defined, heterogeneous clinicopathological syndrome that exhibits myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative features (5), and there are no specific therapeutic strategies for treating patients with CMML. According to laboratory and ancillary tests, cytogenetic abnormalities occur in ~30% of CMML patients, however, there are no consistently recurring chromosomal translocations that can be depended upon for diagnostic criteria, and the incidence of chromosomal translocation in CMML patients is only 1–2% (6).

To determine the role of PDGFRβ gene rearrangement in the pathogenesis of CMML, the current study reports a case of CMML associated with a t(5;14)(q33;q32) fusion gene using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The patient was effectively treated with imatinib, and the relevant literature was reviewed.

Case report

Patient

A patient with CMML was diagnosed, using immunophenotyping and morphological methods, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues (7).

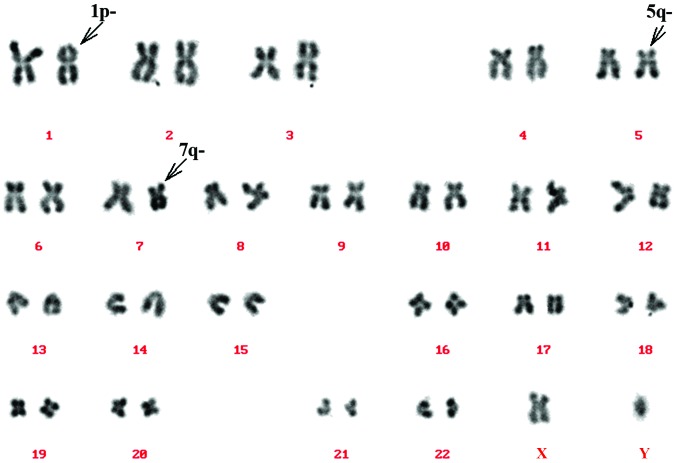

Routine karyotype analysis

A bone marrow sample was collected from the patient (heparin lithium was used as an anticoagulant), and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 20% fetal bovine serum using the direct and short-term culture methods (8). Termination of culture was performed following culturing in colchamine for 1 h, and cells were subsequently fixed in a solution of methanol and glacial acetic acid (methanol:glacial acetic acid, 3:1). Following fixing, cells were collected and chromosome karyotype was analyzed after conventional reverse-banding (9). The remaining cells were stored in fresh fixative and preserved at 20°C. Chromosomes were analyzed according to standard procedures (10) and the karyotype was classified according to ‘An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN 2009)’ (11). The results of karyotype analysis revealed a break in chromosome 5 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Karyotype analysis revealed a break in the long arm of chromosome 5. Derivative chromosomes are indicated by arrowheads.

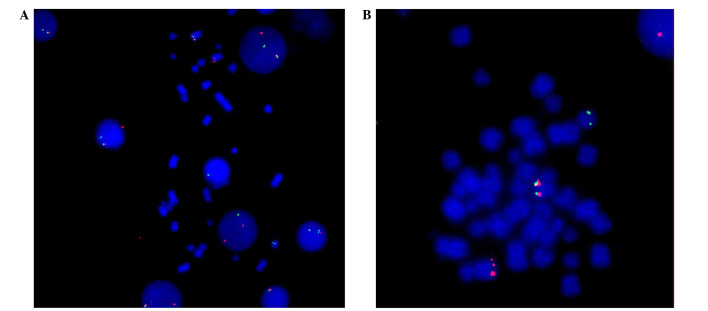

FISH

PDGFRβ isolate probe (Cytocell, Cambridge, UK), which was complementary to the PDGFRβ gene, was applied to the cells, and tagged with green and orange spectroscopy tags. The methods used were previously described by Guo et al (12). Positive abnormal signals, including red and green fluorescence, were detected via FISH. This indicated PDGFRβ gene rearrangement of cells during interphase (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B indicates the gene isolation signals, which were located on chromosomes 5 and 14.

Figure 2.

Gene rearrangement of PDGFRβ was detected via fluorescence in situ hybridization. (A) Red and green fluorescence indicated the PDGFRβ gene rearrangement in interphase cells. (B) Gene isolation signals were located on chromosomes 5 and 14. PDGFRβ, platelet derived growth factor receptor β. Magnification, ×1,000.

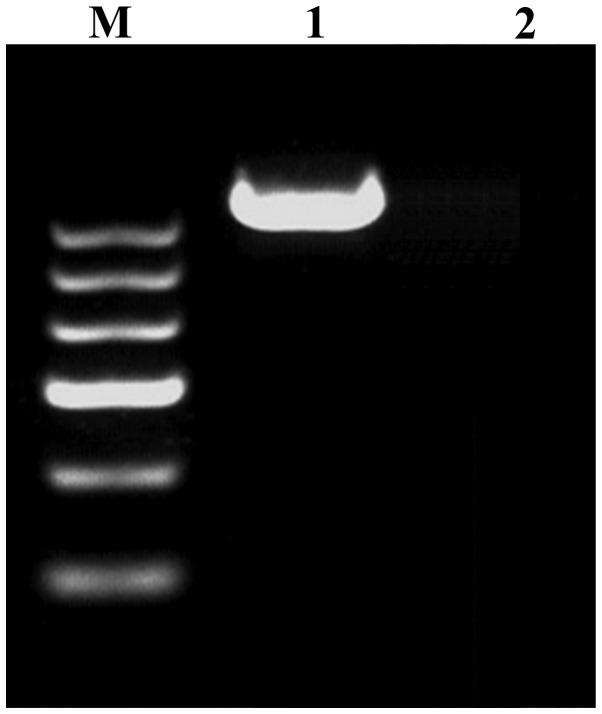

RT-PCR processing

The thyroid hormone receptor interactor 11 (CEV14)-PDGFRβ fusion gene was amplified via PCR, following the protocol described by Huang et al (13). Samples were then analyzed for the presence of the fusion gene product. Briefly, total RNA (1 µg) was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA; 1 µl) was synthesized using the Takara RNA PCR kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. According to the reported translocated genes on chromosome 14, CEV14 (14q32) (14), coiled-coil domain containing 88C (KIAA1509) (14q32) (15) and ninein (GSK3B interacting protein) (NIN) (14q24) (16) primers were selected and designed. The primers utilized were as follows: PDGFRβ forward, 5′-GTGGTGAGCACACTGCGTCTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTAACGTGGCTTCTTCTGCCA-3′; CEV14 forward, 5′-CGCTGCAGCTTTCTGTCTCTCAGGAACAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCGAGGAGCCAAACGGATTTACATCTGTAA-3′; KIAA1509 forward, 5′-CTTATTTGGGATGGAGCCCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCGGGACACAGATAAGA-3′; NIN forward, 5′-TACCAAGAACAGCATTCACCAGGCG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCGGCAGTGCAGGGTACTACAAGAC-3′. The PCR cycling conditions used was as follows: 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. As indicated in Fig. 3, the CEV14-PDGFRβ fusion gene was detected using RT-PCR.

Figure 3.

CEV14-platelet-derived growth factor receptor β fusion gene was detected using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Lanes: M, DNA marker; 1, patient sample; 2, negative control sample from a healthy individual.

Bone marrow morphology and immunophenotyping

A bone marrow smear revealed serious granulopoiesis, monocytosis, accompanying myelodysplasia and an increase in bone marrow blast cell and promonocyte numbers. Hemogram analysis revealed increased monocytic hyperplasia, progranulocytes and promonocytes. Immunophenotyping results confirmed the diagnosis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

Discussion

The WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues (2008) defined a novel category for myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms associated with eosinophilia and abnormalities of PDGFRα, PDGFRβ or fibroblast growth receptor 1 (17). Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN), characterized by dyshematopoiesis and myeloproliferation, may be classified into several types: CMML, atypical chronic myelogenous leukemia, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and MDS/MPN-unclassifiable (18). MDS/MPN occurs primarily in adult men with normal chromosome karyotypes, and the underlying pathogenesis remains to be fully elucidated (6).

Myeloid neoplasms associated with rearrangement of PDGFRβ, demonstrate a PDGFRβ fusion gene on chromosome 5q31–33, and are characterized by fever, weakness, hepatosplenomegaly and, in certain cases, cardiac damage and skin infiltration (19). This type of neoplasm possesses a variety of hematological symptoms, including eosinophilia, monocytosis and characteristics of systemic mastocytosis, for example bone marrow mastocytosis and abnormal expression of cluster of differentiation 25 (17).

The most common chromosome translocation that accompanies PDGFRβ gene rearrangement is t(5;12)(q33;p13) (20). Golub et al (21) confirmed that the juxtaposition of the PDGFRβ gene on chromosome 5 and the ets variant 6 (TEL) gene on the short arm of chromosome 12, which formed the TEL-PDGFRβ fusion gene, sequentially activated the PDGFRβ tyrosine kinase. This enhanced cell proliferation and inhibited apoptosis, thus generating tumor deterioration and metastasis, through the activation of multiple signaling pathways, ultimately leading to the formation of a myeloproliferative disorder (22). The t(5;14) chromosome translocation detected in the present study is rare and, to the best of our knowledge, has been reported in the relevant literature <10 times (14,23–31). The t(5;14) chromosome translocation has been observed to typically be present in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (24,26). The partner genes of PDGFRβ include human homeobox 11-like 2 (Hox11L2) (23,24,28–30) and CEV14 (14,31). Previous studies have revealed that the translocation of chromosomes 5 and 14 is associated with transcriptional activation of the Hox11L2 gene (24), as well as genetic recombination of RAN binding protein 17-T-cell leukemia, homeobox protein 3 and B-cell lymphoma 11B (26). In the relevant literature, CEV14-PDGFRβ fusion gene on t(5;14)(q33;q32) has been identified in two reported cases: One T-ALL (31) and one acute myeloid leukemia case (14). The latter of these cases demonstrated that CEV14-PDGFRβ was capable of accelerating the formation of leukemia, and thus may be a direct cause of cancer formation (14). Furthermore, the presence of the CEV14-PDGFRβ fusion gene in T-ALL was concluded to be associated with a high rate of relapse (31). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to report a case of CMML associated with t(5;14)(q33;q32), and further studies may be required in order to investigate the association between the chromosome translocation and an increased recurrence rate of CMML.

Myeloid tumors associated with PDGFRβ gene rearrangement have been a significant research focus, due to their susceptibility to drug therapy and high rate of complete remission (20,32–35). With the exception of protein kinase cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent type II-PDGFRβ, PDGFRβ fusion genes are capable of forming dimers with receptors, which leads to autophosphorylation, and thus induces the persistent activation of tyrosine kinases. Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is typically used to treat myeloid tumors exhibiting PDGFRβ fusion, in order to achieve sustained remission (20,32,36). Due to potential side-effects, including adverse drug reactions following multiple administrations, a limited daily dosage of imatinib has been recommended (37). The serum creatinine value of the patient in the present study gradually increased following treatment with imatinib (400 mg/day) for 4 days, thus the daily dosage of imatinib was reduced to 300 mg/day. On day 5 of treatment, percussive pain over the left renal region and hematuria were detected, and kidney stones were diagnosed by ultrasound. Therefore, a reduced dosage of imatinib was subsequently administered (100 mg/day), and kidney-sparing surgery was successfully performed in order to prevent deterioration of the patient. As symptoms were controlled by using a lower dose of imatinib, low dosages of imatinib may be an effective therapy for MDS/MPN associated with PDGFRβ-CEV14, however the long-term curative effects of this therapeutic strategy require further investigation.

Detection of PDGFRβ-associated fusion genes in individual patients appears to be necessary for definitive diagnosis, guiding treatment, predicting prognosis and monitoring minimal residual disease in MDS/MPN. In the present study, an elderly patient was diagnosed with a myeloid tumor associated with the PDGFRβ-CEV14 fusion gene, using the methods of FISH and RT-PCR. These methods were therefore proven to be of significant value in improving diagnosis, guiding treatment and increasing the cure rate of MDS/MPN patients, via the detection of multiple genes exhibiting rearrangement, which are associated with PDGFRβ in MDS/MPN.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Beijing, China; grant no. 81200383).

References

- 1.Reilly JT. Class III receptor tyrosine kinases: Role in leukaemogenesis. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:744–757. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1048.2001.03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heldin CH, Ostman A, Rönnstrand L. Signal transduction via platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:F79–F113. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donovan J, Shiwen X, Norman J, Abraham D. Platelet-derived growth factor alpha and beta receptors have overlapping functional activities towards fibroblasts. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2013;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demoulin JB, Enarsson M, Larsson J, Essaghir A, Heldin CH, Forsberg-Nilsson K. The gene expression profile of PDGF-treated neural stem cells corresponds to partially differentiated neurons and glia. Growth Factors. 2006;24:184–196. doi: 10.1080/08977190600696430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steensma DP, Tefferi A, Li CY. Splenic histopathological patterns in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with clinical correlations: reinforcement of the heterogeneity of the syndrome. Leuk Res. 2003;27:775–782. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emanuel PD. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:1335–1342. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vardiman JW. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: an overview with emphasis on the myeloid neoplasms. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;184:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finelli P, Giardino D, Rizzi N, Buiatiotis S, Virduci T, Franzin A, Losa M, Larizza L. Non-random trisomies of chromosomes 5, 8 and 12 in the prolactinoma sub-type of pituitary adenomas: conventional cytogenetics and interphase FISH study. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:344–350. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000501)86:3<344::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma RS, Dosik H. The value of reverse banding in detecting bone marrow chromosomal abnormalities: Translocation between chromosomes 1, 9, and 22 in a case of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) Am J Hematol. 1977;3:171–175. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830030208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claussen U, Michel S, Mühlig P, Westermann M, Grummt UW, Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Liehr T. Demystifying chromosome preparation and the implications for the concept of chromosome condensation during mitosis. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;98:136–146. doi: 10.1159/000069817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaffer LG, Slovak ML, Campbell LJ, editors. ISCN 2009: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (2009): Recommendations of the International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. 1st. Switzerland: S Karger AG; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo B, Da WM, Han XP, Zhao DD, Jin HJ, Wang K, Tang JY. Study of BCR-ABL gene rearrangement by dual-color-dual-fusion fluorescence in situ hybridization on acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Chin J Lab Med. 2006;10:902–905. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang W, Cao Q, Lu Y. Detection on BCR-ABL fusion gene in Ph1 chromosome positive leukemia by ‘nested’ retrotranscriptase/polymerase chain reaction. Chin J Hema. 1992;13:183–186. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abe A, Emi N, Tanimoto M, Terasaki H, Marunouchi T, Saito H. Fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β to a novel gene CEV14 in acute myelogenous leukemia after clonal evolution. Blood. 1997;90:4271–4277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Sternberg DW, Wlodarska I, Galinsky I, Stone RM, DeAngelo DJ, Gilliland DG, Cools J. KIAA1509 is a novel PDGFRB fusion partner in imatinib-responsive myeloproliferative disease associated with a t(5;14)(q33;q32) Leukemia. 2005;19:27–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vizmanos JL, Novo FJ, Román JP, Baxter EJ, Lahortiga I, Larráyoz MJ, Odero MD, Giraldo P, Calasanz MJ, Cross NC. NIN, a gene encoding a CEP110-like centrosomal protein, is fused to PDGFRB in a patient with a t(5;14)(q33;q24) and an imatinib-responsive myeloproliferative disorder. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2673–2676. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bain BJ, editor. Leukaemia Diagnosis. 4th. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Provan A, Baglin T, Dokal I, de Vos J, editors. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Haematology. 3rd. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. Myelodysplasia; pp. 244–247. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walz C, Metzgeroth G, Schoch C, Haferlach T, Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Cross NCP, Reiter A. Characterization of two new imatinib-responsive fusion genes generated by disruption of PDGFRB in eosinophilia-associated chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2006;108:667. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apperley JF, Gardembas M, Melo JV, Russell-Jones R, Bain BJ, Baxter EJ, Chase A, Chessells JM, Colombat M, Dearden CE, et al. Response to imatinib mesylate in patients with chronic myeloproliferative diseases with rearrangements of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:481–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golub TR, Barker GF, Lovett M, Gilliland DG. Fusion of PDGF receptor beta to a novel ets-like gene, tel, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with t(5;12) chromosomal translocation. Cell. 1994;77:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie KA, Aprikyan AA, Bowen-Pope DF, Norby-Slycord CJ, Conyers S, Bartelmez S, Sitnicka EH, Hickstein DD. The Tel-PDGFRbeta fusion gene produces a chronic myeloproliferative syndrome in transgenic mice. Leukemia. 1999;13:1790–1803. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hélias C, Leymarie V, Entz-Werle N, Falkenrodt A, Eyer D, Costa JA, Cherif D, Lutz P, Lessard M. Translocation t(5;14)(q35;q32) in three cases of childhood T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A new recurring and cryptic abnormality. Leukemia. 2002;16:7–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard OA, Busson-LeConiat M, Ballerini P, et al. A new recurrent and specific cryptic translocation, t(5;14)(q35;q32), is associated with expression of the Hox11L2 gene in T acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2001;15:1495–1504. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haider S, Matsumoto R, Kurosawa N, et al. Molecular characterization of a novel translocation t(5;14)(q21;q32) in a patient with congenital abnormalities. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:335–340. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su XY, Della-Valle V, Andre-Schmutz I, et al. HOX11L2/TLX3 is transcriptionally activated through T-cell regulatory elements downstream of BCL11B as a result of the t(5;14)(q35;q32) Blood. 2006;108:4198–4201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-032953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger R, Dastugue N, Busson M, Van Den A kker J, Pérot C, Ballerini P, Hagemeijer A, Michaux L, Charrin C, Pages MP, et al. Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique (GFCH): t(5;14)/HOX11L2-positive T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A collaborative study of the Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique (GFCH) Leukemia. 2003;17:1851–1857. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Zutven LJ, Velthuizen SC, Wolvers-Tettero IL, van Dongen JJ, Poulsen TS, MacLeod RA, Beverloo HB, Langerak AW. Two dual-color split signal fluorescence in situ hybridization assays to detect t(5;14) involving HOX11L2 or CSX in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2004;89:671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagel S, Scherr M, Kel A, Hornischer K, Crawford GE, Kaufmann M, Meyer C, Drexler HG, MacLeod RA. Activation of TLX3 and NKX2–5 in t(5;14)(q35;q32) T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia by remote 3′-BCL11B enhancers and coregulation by PU.1 and HMGA1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1461–1471. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavé H, Suciu S, Preudhomme C, Poppe B, Robert A, Uyttebroeck A, Malet M, Boutard P, Benoit Y, Mauvieux L, et al. EORTC-CLG: Clinical significance of HOX11L2 expression linked to t(5;14)(q35;q32), of HOX11 expression, and of SIL-TAL fusion in childhood T-cell malignancies: Results of EORTC studies 58881 and 58951. Blood. 2004;103:442–450. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi HT, Zhou F, Hou J, Wei W, Guo LP, Zhang YX. A case of T-cell acute lymphpoblastic leukemia with translocation t(5;14) (q33; q32) J Chin Hematol. 2013;06:800. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson K, Velloso ER, Lopes LF, Lee C, Aster JC, Shipp MA, Aguiar RC. Cloning of the t(1;5)(q23;q33) in a myeloproliferative disorder associated with eosinophilia: Involvement of PDGFRB and response to imatinib. Blood. 2003;102:4187–4190. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baxter EJ, Kulkarni S, Vizmanos JL, Jaju R, Martinelli G, Testoni N, Hughes G, Salamanchuk Z, Calasanz MJ, Lahortiga I, et al. Novel translocations that disrupt the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB) gene in BCR-ABL-negative chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:251–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cross NC, Reiter A. Tyrosine kinase fusion genes in chronic myeloproliferative diseases. Leukemia. 2002;16:1207–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salaroli A, Loglisci G, Serrao A, Alimena G, Breccia M. Fasting glucose level reduction induced by imatinib in chronic myeloproliferative disease with TEL-PDGFRβ rearrangement and type 1 diabetes. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1823–1824. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallagher G, Horsman DE, Tsang P, Forrest DL. Fusion of PRKG2 and SPTBN1 to the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta gene (PDGFRB) in imatinib-responsive atypical myeloproliferative disorders. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;181:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka MF, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Ohanian M, Jabbour E. Treatment options for chronic myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin Pharmaco. 2012;13:815–828. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.671296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]