Abstract

Chronic infection by hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the main risk factors for the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, the emergence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in non-cirrhotic HCV patients, especially after sustained virological response (SVR) is an unusual event. Recently, it has been suggested that HCV genotype 3 may have a particular oncogenic mechanism, but the factors involved in these cases as well as the profile of these patients are still not fully understood. Thus, we present the case of a non-cirrhotic fifty-year-old male with HCV infection, genotype 3a, who developed HCC two years after treatment with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin, with SVR, in Brazil.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatitis C, Genotype 3, Sustained virological response, Non-cirrhotic liver

Abstract

A infecção crônica pelo vírus da hepatite C é um dos principais fatores de risco para o desenvolvimento de cirrose hepática e carcinoma hepatocelular. Entretanto, o surgimento do carcinoma hepatocelular em pacientes portadores de hepatite C na ausência de cirrose, especialmente após o tratamento e a obtenção de resposta virológica sustentada, é um evento incomum. Recentemente tem sido sugerido que o genótipo 3 do vírus da hepatite C possa ter um mecanismo oncogênico particular, mas todos os fatores envolvidos nestes casos, assim como o perfil destes pacientes, ainda não estão totalmente esclarecidos. Deste modo, apresentamos o caso de um paciente masculino de 50 anos de idade, com infecção pelo vírus da hepatite C genótipo 3a, não cirrótico, que desenvolveu carcinoma hepatocelular dois anos após ter atingido resposta virológica sustentada com o tratamento com interferon peguilado e ribavirina.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic infection by hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the main risk factors for liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide6 , 11 , 14. In recent decades, the incidence of HCC seems to be changing, especially in areas previously considered at low prevalence. This seems likely to be associated with the increase in the number of cases of HCV-related cirrhosis in these regions5 , 9. In Brazil, about 54% of HCC are associated to HCV-related cirrhosis, according to a national survey5. In contrast with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, the emergence of HCC in non-cirrhotic HCV patients is an unusual event9 , 10. In chronic HCV patients, the risk of HCC is proportionate to the liver fibrosis stage, with an annual rate of 0.5-10% of developing HCC in a cirrhotic liver, according to the region studied11 , 14 , 17.

The introduction of interferon (IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) in the management of HCV provided a significant advance in the attempt to modify the natural course of liver disease in patients with chronic HCV infection17. Several studies have examined the effect of this therapy on the incidence of HCC14 , 15 , 17 , 20. Current data indicate that patients treated with antiviral therapy, who achieve sustained virological response (SVR) have a reduction in all-cause mortality, including progression of liver disease9 , 14. Furthermore, patients with SVR present an important improvement in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis, and consequently a reduction in the risk of developing HCC 3 , 14 , 17 , 18. However, the presence of HCC in non-cirrhotic patients with SVR is possible and Asia practically monopolizes existing accounts, especially Japan1 , 12 , 16. The factors involved in these cases as well as the profile of these patients are still not fully understood. Thus, we deem it relevant to describe an unusual case of HCC in a non-cirrhotic patient after HCV treatment with pegylated IFN (pegIFN) and RBV, years after SVR, in Brazil.

CASE REPORT

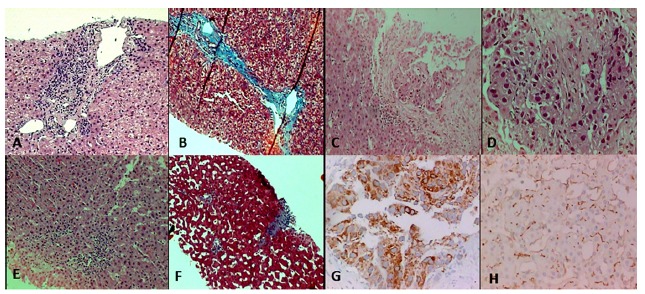

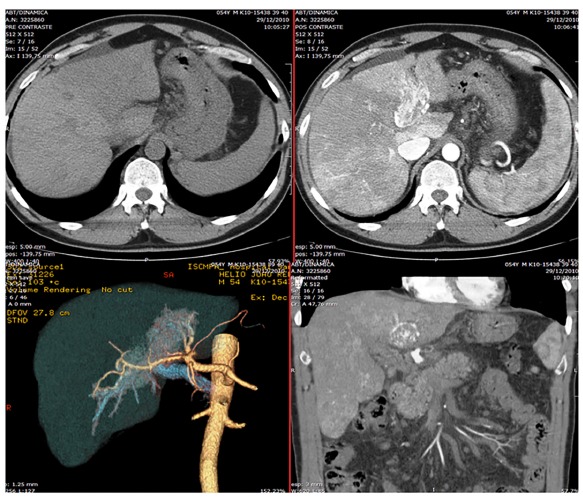

A Caucasian fifty-year-old male had HCV infection diagnosis in routine exams in 2007. Further evaluation showed a genotype 3a, with a viral load of 156.789 IU/mL by HCV-RNA quantitative PCR (real time - polymerase chain reaction, reference value < 12 UI/mL) , baseline gamma-glutamyl transferase (gGT) levels of 90 U/L (normal value: 8-61 U/L) and elevated aminotransferase levels - serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 110 U/L (normal value: 7-56 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 192 (normal value: 5-40 U/L). The additional laboratory exams showed normal liver function markers (albumin, bilirubin and prothrombin), negative serum markers for HBV, absence of abnormalities in blood glucose values and normal hematologic counts. The physical examination revealed a eutrophic patient and no signs of chronic liver disease. The abdominal ultrasound (US) was normal and without signs of advanced chronic liver disease or portal hypertension. There were no reports of comorbidities like diabetes, obesity, other infections, or alcohol abuse. Liver biopsy was performed and considered representative. A total of two fragments and 11 portal tracts were analyzed; the length and width of the greatest fragment was 1.0 x 0.3 cm, respectively. This biopsy showed chronic hepatitis with intense interface activity and a few fibrous septa (Fig. 1- A and B), classified as Metavir2 A3-F2. There was no hepatic steatosis or other relevant findings, like siderosis, small cell change, or even dysplasia. As soon as possible, he began the treatment with pegIFN and RBV for six months, achieving SVR and normalizing ALT and AST. He remained with negative HCV-RNA evaluated by real-time PCR, normal aminotransferases, and asymptomatic for two years, when nonspecific abdominal pain appeared, without other symptoms or alarm signals. A new abdominal US showed portal vein thrombosis. Thrombophilia was ruled out, and an abdominal CT scan was performed. Surprisingly, it demonstrated a portal vein thrombosis with arterial enhancement, associated with nonspecific hypodense nodules in the right hepatic lobe (Fig. 2). The magnetic resonance imaging evidenced the same characteristics of portal thrombosis, besides several nodular images of different sizes, the largest one with 1.8 cm, without typical vascular pattern6. The alpha-fetoprotein level was 4.5U/L. We decided to do a tomography to guide a biopsy of the lesion in the right lobe and a biopsy away of the lesion, in the left hepatic lobe. The biopsy evidenced a moderately differentiated HCC with trabecular pattern (Fig. 1 - C and D). There was no vessel or stromal invasion documented in the sample. The non-tumorous liver tissue remained without evidence of cirrhosis - Metavir A1-F1 (Fig. 1 - E and F). Further to this, we performed immunohistochemistry to confirm the histogenesis of this neoplasia, that showed positivity for typical antibodies related to hepatocellular carcinoma10 which were hepatocyte-specific antigen (HSA) and canalicular staining of: pCEA, CD10 and Villin (Fig. 1 - G and H). These features, associated with the presence of vascularization in the portal thrombus, led to the conclusion that the portal thrombosis corresponded to macrovascular tumor invasion and Sorafenib was prescribed. Despite this, the patient developed jaundice, signs of portal hypertension, with ascites and variceal bleeding, progressing to death in four months.

Fig. 1. - Histological images. A - Pretreatment liver biopsy: interface activity (hematoxylin-eosin, 100x). B - Pretreatment liver biopsy: fibrous septa (Masson's trichrome, 100x). C - Liver section from the tumor: moderately differentiated HCC (hematoxylin-eosin, 100 x). D - Liver section from the tumor: moderately differentiated HCC in detail (hematoxylin-eosin, 400x). E - Post treatment liver biopsy: non-tumoral tissue with mild activity (hematoxylin-eosin, 40 x). F - Post treatment liver biopsy: portal fibrosis (Masson's trichrome, 40x). G - HCC, immunohistochemistry: hepatocyte-specific antigen (400 x). H - HCC, immunohistochemistry: CD 10, canalicular staining (400 x).

Fig. 2. - Abdominal computadorized tomography scan in different sections: note the portal vein thrombosis and nonspecific hypodense nodules in the right hepatic lobe.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of HCC in patients without advanced hepatic fibrosis, years after treatment for HCV and with SVR, has been reported in Asian patients, particularly in Japanese ones1 , 9 , 12 , 18, where HCV infection is endemic and the prevalence of HCC is high. In the Occident, we found few similar cases published in the literature3 , 19, one of the reasons why we deem important to present this case.

In the United States, when LOK et al.11 assessed the role of maintaining reduced doses of pegIFN in patients with chronic HCV liver disease, in order to prevent complications, they demonstrated the existence of HCC in patients without cirrhosis, but emphasizing the importance of the presence of advanced fibrosis. The case presented here is relevant since it shows an HCC that affects a patient with HCV and without advanced fibrosis, two years after SVR, and with documented fibrosis regression outside the tumor area. Previous studies have strongly suggested that SVR can minimize the histological and clinical deterioration, resulting in improvement of liver histology7. The benefits of successful antiviral therapy in chronic HCV has been recently reaffirmed by MOON et al.13 in a study that retrospectively reviewed 463 patients who underwent pegIFN and RBV therapy, where patients without cirrhosis and with SVR had a significant lower risk of progression to cirrhosis compared to non-SVR and, moreover, SVR was related to reduction in the risk of HCC development. As in the present case, MOON et al.13 also found two patients with SVR and no evidence of cirrhosis before HCC diagnosis. However, the exclusion of cirrhosis in these two patients was made based on clinical criteria, which is not a reliable method to assess if advanced fibrosis has already been detected histologically. In the presented case, two biopsies at different times, including the diagnosis of HCC, have pointed to the absence of significant fibrosis.

It is suggested that the risk factors for the development of HCC in the absence of advanced fibrosis in HCV pretreatment patients are male gender, advanced age, persistently elevated aminotransferases, hepatic steatosis, diabetes, and alcohol abuse3 , 9. The frequent association of HCV, especially genotype 3, with steatosis deserves mention in this context, as this parameter correlates with HCC8. In this case, despite being male and genotype 3, the patient had none of the other afore mentioned risk factors, including absence of steatosis on pretreatment and tumor biopsies.

In HCV eradicated patients, risk factors for the development of HCC remain not entirely clear. SATO et al.17 reported that in their experience, men with documented advanced liver fibrosis, and low levels of serum albumin and elevated pretreatment alpha-fetoprotein, are more likely to develop HCC within five years of HCV eradication. All these findings suggest a possible more advanced liver disease as the basis for development of HCC; however, these features curiously did not occur in the present case.

Recently, other risk factors for the development of HCC, independent of the degree of hepatic fibrosis, have been studied. HUANG et al.9, in a prospective cohort of 642 individuals, found an interesting association between high baseline gGT levels before IFN-based anti-HCV therapy using a cut-off value of 75U/L and development of HCC in non-cirrhotic patients with SVR, but the pathophysiological mechanism of this association remains unclear. Furthermore, the possibility that the genotype 3 HCV might have a particular oncogenic process has been considered, possibly by means of alteration in chromosome 10, causing disturbances in tumor suppression and increasing the incidence of HCC, which could remain even after HCV clearance and independent of the fibrosis degree8. In the present case, the hypothesis that genotype 3 may have an important role in the emergence of HCC should be considered, as well as high baseline gGT levels, especially in this context of lack of significant fibrosis.

In current literature, recommendations for monitoring and surveillance of these patients with chronic HCV without cirrhosis are scanty and conflicting. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases4 describes that the benefit of maintaining surveillance in patients with HCV and Metavir F3 is uncertain, not routinely recommended. On the other hand, the European Association for the Study of the Liver6 recommended that patients with chronic HCV and Metavir F3 should be included in surveillance programs, since the transition to cirrhosis cannot be accurately defined. These same authors also recommend maintaining surveillance in patients treated for HCV who have advanced fibrosis, even after SVR.

In conclusion, the possibility of developing HCC in patients without advanced fibrosis suggests the existence of other factors that are still unclear in the pathogenesis of HCV, raising questions regarding the need to perform the follow-up of these patients, even after SVR. The new evidence that HCV genotype 3 has become a problem in hepatitis C patients either by the response rate to IFN-free therapy regimens or the possibility of independent mechanisms of carcinogenesis8, a point that needs further studies.

ABBREVIATIONS

HCV - Hepatitis C virus

HCC - Hepatocellular carcinoma

HBV - Hepatitis B virus

IFN - Interferon

RBV - Ribavirin

SVR - Sustained virologic response

pegIFN - Pegylated interferon

PCR - Polymerase chain reaction

gGT - Gamma-glutamyl transferase

ALT - Alanine aminotransferase

AST - Aspartate aminotransferase

US - Ultrasound

HSA - Hepatocyte-specific antigen

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Nozha OM, Al Ashgar H, Khan M, Al Mana H. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of liver cirrhosis in a treated hepatitis C virus patient. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:235–236. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289–293. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertolini E, Bassi F, Fornaciari G. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma in a non-cirrhotic, long-term responder to antiviral therapy, chronic hepatitis C patients: what kind of surveillance? Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:80–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrilho FJ, Kikuchi L, Branco F, Gonçalves CS, Mattos AA, Brazilian HCC Study Group. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of hepatocellular carcinoma in Brazil. Clinics. 2010;65:1285–1290. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001200010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George SL, Bacon BR, Brunt EM, Mihindukulasuriya KL, Hoffmann J, Di Bisceglie AM. Clinical, virologic, histologic, and biochemical outcomes after successful HCV therapy: a 5-year follow-up of 150 patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:729–738. doi: 10.1002/hep.22694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goossens N, Negro F. Is genotype 3 of the hepatitis C virus the new villain? Hepatology. 2014;59:2403–2412. doi: 10.1002/hep.26905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang CF, Yeh ML, Tsai PC, Hsieh MH, Yang HL, Hsieh MY. Baseline gamma-glutamyl transferase levels strongly correlate with hepatocellular carcinoma development in non-cirrhotic patients with successful hepatitis C virus eradication. J Hepatol. 2014;61:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karabork A, Kaygusuk G, Ekinci C. The best immunohistochemical panel for differentiating hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lok AS, Seeff LB, Morgan TR, Di Bisceglie AM, Sterling RK, Curto TM. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and associated risk factors in hepatitis C-related advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:138–148. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyano S, Togashi H, Shinzawa H, Sugahara K, Matsuo T, Takeda Y. Case report: occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma 4. 5 years after successful treatment with virus clearance for chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:928–930. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon C, Jung KS, Kim do Y, Baatarkhuu O, Park JY, Kim BK. Lower incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis in hepatitis C patients with sustained virological response by pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:573–581. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:329–337. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng V, Saab S. Effects of a sustained virologic response on outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:923–930. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nojiri K, Sugimoto K, Shiraki K, Kusagawa S, Tanaka J, Beppu T. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C more than 10 years after sustained virological response to interferon therapy. Oncol Lett. 2010;1:427–430. doi: 10.3892/ol_00000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato A, Sata M, Ikeda K, Kumada T, Izumi N, Asahina Y. Clinical characteristics of patients who developed hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis C virus eradication with interferon therapy: current status in Japan. Intern Med. 2013;52:2701–2706. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sewell JL, Stick KM, Monto A. Hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virologic response in hepatitis C patients without cirrhosis on a pretreatment liver biopsy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:225–229. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32831101b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabibian JH, Landaverde C, Winn J, Geller SA, Nissen NN. Hepatocellular carcinoma in a hepatitis C patent with sustained viral response and no fibrosis. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang CH, Xu GL, Jia WD, Li JS, Ma JL, Ge YS. Effects of interferon treatment on development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic virus infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1254–1264. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]